Abstract

Purpose of Review

Radiotherapy has been considered in the past an option for local control of resectable lung cancer only in cases of patients considered unfit or declining surgical treatment.

Recent Findings

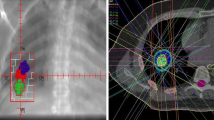

Recent technological improvements allow radiation oncologists to deliver precisely targeted radiation at much higher doses compared to traditional radiation therapy, in one single or few sessions, minimizing damage to the surrounding healthy tissue. In this review, we discuss the advantages and inconveniences of surgery and stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for the treatment of resectable non-small cell lung cancer.

Summary

Although the use of modern surgical techniques has decreased the overall rate of adverse effects and mortality of lung resection, surgery-related morbidity is not comparable to that recorded after SBRT. This advantage has to be balanced against, in some cases, lack of definite cyto-histological diagnosis and non-accurate definitive pathological staging. In the absence of high-quality randomized trials comparing surgery and SBRT, the published 1- and 3-year survival rates after SBRT seem to be comparable to lung resection. Nevertheless, we have to be cautious in recommending non-surgical therapy for operable patients having resectable tumours due to the aforementioned limitations biasing the results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Surgical resection has been considered the gold standard for local control in resectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), in spite of the fact that its superiority over other local therapeutic alternatives has never been tested by randomized clinical trials (RCT) [1]. The use of modern mini-invasive techniques in surgery and improved perioperative care has contributed to a dramatic decrease of the rate of postoperative adverse effects and 30-day mortality for NSCLC patients treated surgically [2••].

On the other hand, technological improvements in radiation equipment (optimal planning, target delineation, image guidance and patient immobilization and synchrony with respiratory movements) allow for high radiation delivery even to small tumours with very precise margins (1–2 millimetres), avoiding damage to healthy surrounding tissues. Basically, SBRT delivers radiation at much higher doses, compared to previous techniques, in very short periods of time: usually no more than 1–2 weeks and, in some protocols, in only 1–2 fractions [2••].

Although initially SBRT was restricted to non-operable patients—or those refusing surgery—the lack of sound evidences on the superiority of surgery and the publication of promising results in early NSCLC treated with SBRT [3] have made the hypothesis of non-superiority of surgery compared to SBRT worthy to be tested.

Although anatomical resection can be safely performed today by minimally invasive techniques preserving pulmonary function [4] and with good long-term survival in selected cases [5], this review has been written from the understanding that lobectomy plus mediastinal lymph node dissection still has to be considered the treatment of choice for early stage NSCLC [6, 7], and the surgical techniques against SBRT have to be compared.

To our mind, the most relevant questions to be answered to facilitate decision-making in daily practice are the following:

Question 1: Who Should be Considered a Non-operable Patient?

Some recently published papers reporting experiences where SBRT was used as definitive therapy for resectable tumours only include “medical inoperability” or similar terms as major criteria for patients’ selection [8, 9]. The concept “medical inoperability” can be understood in different ways, depending on the local protocols and practices. In our settings, we have adopted the recommendations published in 2013 to evaluate functional operability, with some modifications to adapt to our local practices (Fig. 1).

Recommended flow chart to facilitate decision-making in our settings. Asterisk in some instances, clinical N2 disease can be judged to be resectable (see text) but SBRT is usually not considered in such cases. Double asterisk the Revised Thoracic Cardiac Risk Index for Preoperative Risk estimates the risk of cardiac complications after surgery. See reference 10. Dollar Estimated postoperative FEV1 % and DLCO %. See reference 10. Ampersand VATS lobectomy plus systematic mediastinal lymph node dissection

Basically, the Thoracic Revised Cardiac Risk Index for lung resection [10] is calculated first. If the patient is considered as having high risk of major cardiac postoperative complication, cardiac consultation is advisable and the surgical decision is postponed. In all cases, FEV1 % and DLCO % are measured and postoperative values estimated [10]. Surgery is indicated straightforward if both values are over 60 %. In case one of those values is under 30 %, no surgical treatment is recommended. Between 31 and 60 %, exercise tests with estimation of VO2max are indicated, and surgery is not recommended if the value is 10 ml/(kg min) or lower.

Patient’s age per se is never considered a contraindication for surgery, but the advantages and risks of surgery are carefully discussed with patients over 85. Of course, all therapeutic decisions in NSCLC patients are adopted after discussion in a multidisciplinary team (MDT). MDT management has become the standard of care in some countries, after some advantages to both the patient and the clinicians have been demonstrated [11]. In our practice, we noticed a slight decrease in lung resection-related mortality after implementing internationally accepted guidelines and MDT agreement before indicating surgical therapy for lung cancer patients [12].

Question 2: How to Define as “Resectable” a Case of NSCLC?

Lung cancer can be successfully and completely resected using different techniques according to the local extent of the disease. On the other hand, the agreement with the type of resection originally planned and the one finally performed is not 100 % due to intraoperative findings forcing the surgical team to a more extended resection [13]. Obviously, the higher the clinical T status, the bigger the rate of discordance between planned and performed surgery due to local invasion of mediastinal tissues. Although some reported experiences on SBRT for T3 and T4 tumours can be found in the literature [14], the technique is usually reserved to peripheral small tumours [2••]. Thus, when comparing the effectiveness of surgery and SBRT, only comparable cases—in terms of clinical staging—can be selected to avoid biasing the conclusions. Only well organized and managed MDTs where surgeons are actively involved guarantee the accurate selection of cases to avoid exploratory operations or incomplete resections.

The N factor represents a more debatable aspect to be considered when discussing case selection and survival of patients treated with SBRT or surgery, as we are commenting below. To note is the fact that, even in completely clinically staged patients, the rate of intraoperatively found N2 disease is not negligible, representing more than 5 % of the cases, as we are discussing below [15]. While in Europe there is a current trend to consider limited N2 as a resectable disease, due to favourable outcomes with surgery [15–17], it is not the same in most centres in the U.S. [18].

Question 3: Are Patients Treated by SBRT Correctly Staged?

Before dealing with the staging issue, we have to underline that even high-quality papers reporting retrospective analysis of series of early stage NSCLC patients treated with SBRT [19, 20] included cases having no histologic diagnosis, potentially biasing the survival analysis.

As we have commented above, the finding of unsuspected N2 after mediastinal dissection is not rare, hence the relevance of thorough mediastinal evaluation before recommending SBRT in supposed early stage NSCLC. In the previously quoted study from Obiols and colleagues [15] on unsuspected N2 disease after mediastinal staging according to ESTS guidelines [21], 406 of 540 patients underwent surgical exploration of the mediastinum before resection, whereas the remaining 134 underwent up-front surgery. After surgical staging of the mediastinum, unsuspected N2 disease was identified in 9 % of patients, of whom 80 % had single-station N2 disease and 90 % of these received adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Importantly, the 3- and 5-year survival rates for these patients with unsuspected N2 disease were 80 and 40 %, respectively. In the aforementioned publication by Rocco et al. [18], the reported rate of unsuspected N2 after lobectomy was 8 % in the STS database and 14 % in the European registry. There is no reason to think that in SBRT patients these rates are different. Furthermore, there is vast evidence that some patients with lymph node metastases detected at the time of surgery could have an overall survival benefit from adjuvant therapies [22].

The accuracy of combined positron emission tomography and computed tomography(FDG-PET/CT) in detecting mediastinal metastases is around 80 %, with positive and negative predictive values of 56.3 and 87.7 %, respectively. [23] Low maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of the tumour, diagnosis of adenocarcinoma and small tumour size have been associated to false-negative results.

In case of positive mediastinal lymph nodes at FDG-PET, the ESTS guidelines for preoperative mediastinal lymph node staging for NSCLC recommend invasive tissue confirmation [24]. Fine-needle aspiration guided by endosonography—endobronchial ultrasonography (EBUS) and esophageal ultrasonography (EUS)—is the first choice, due to its high negative predictive value [25]. Surgical staging with nodal dissection or biopsy would be indicated only if endosonography is negative. The combined use of endoscopic and surgical staging results in the highest accuracy [24]. FDG-PET/CT underestimates the spread of cancer into N1 lymph nodes; thus, candidates to SBRT may benefit from increased pathologic evaluation of N1 nodal stations in addition to N2 nodes [26].

The inferiority of the clinical staging performed in patients treated by SBRT compared to surgically treated cases is demonstrated by the higher rates of mediastinal relapse after SBRT [8].

Based on the previous data, invasive nodal staging procedures should be indicated in early stage NSCLC patients, when SBRT is considered, to rule out mediastinal spread in spite of negative mediastinal images.

Question 4: Is the Rate of Adverse Events After Surgery Comparable to SBRT?

Data about morbidity and mortality after lung cancer resection are widely available and can be easily quoted. According to the ESTS Data Base Annual Report [27], the current European 30-day mortality rate for lobectomy in lung cancer patients is 1.9 %, with a trend to decrease especially in VATS cases (Fig. 2). Cardio-pulmonary morbidity (including any kind of adverse event) is over 17 % after lobectomy [27].

Hospital mortality after VATS lobectomy represented in CUSUM plot. To note is a continuous decrease in the occurrence of mortality in the last period of time (after around case 250). SBRT, being the best and up-to-date therapy, has to be compared to modern surgical techniques. Data from the ESTS Database (see reference [27])

Contrary to what happens in surgery, papers aimed to systematically describe complications after SBRT are not easy to find [28••]. Even well-documented reviews [29] comparing SBRT and surgery omit any reference to early or late morbidity after SBRT, while providing thorough data on local control rates and survival. Additionally, some confusion is connected to the fact that SBRT-related morbidity is graded differently depending on the target organ [30–32]. Patient death has also been correlated to SBRT, if indicated for centrally located tumours. A phase II trial from the Indiana University of 70 patients reported that SBRT was a possible contributing factor in 6 patient deaths [33]. In five cases, death resulted from pulmonary infection in patients with delayed radiation pneumonitis. Severe radiation pneumonitis is rarely reported after SBRT, and its occurrence is mostly related to central location of the tumour and neoplasms with gross tumour volume of more than 10 mL [32]. A deleterious delayed effect of SBRT on pulmonary volumes has been rarely reported after treating peripheral nodules. In some published experiences, [34, 35] no impairment is found on the values of FEV1 % and FVC % 3–4 months after completing the treatment and, in some instances, a slight increase is reported in pulmonary volumes.

In the majority of cases after SBRT, only grade 1 or 2 toxicity [36] is published and it is resolved a few months after SBRT. It has been estimated that the risk of developing rib fractures within 2 years of SBRT can be as high as 42 % with a median time of 17 months [30, 31].

Question 5: Do Patients Treated by Surgery Survive Longer?

This question has been addressed in two randomized trials whose results have been pooled and published together [3]. Although the authors of the pooled analysis concluded that SABR can be considered a treatment option in operable patients fit for lobectomy, both trials were considerably biased and their conclusions arguable as we have reported elsewhere [37].

In the absence of high-quality randomized trials, some quasi-experimental retrospective analyses on the subject have been published. In the study by Matsue et al. [38], the authors retrospectively reviewed all patients unfit for lobectomy treated either by SBRT or sub-lobar resection. Cases were conveniently matched according to clinical characteristics. The cumulative incidence of cancer-specific death was comparable between both groups. In a similar study [39], the authors found that the overall recurrence (local and distant) was significantly higher after SBRT, but no statistically significant difference between the two groups in disease-free 3-year survival was found. Previously published articles comparing SBRT versus sub-lobar resection have been systematically reviewed by Mahmood et al. [40••]. The authors collected 18 papers representing the best evidence to the date of publication, and concluded that 1-year survival was similar between patients treated with SABR (around 85 %) and sub-lobar resection (92 %); however, overall 3-year survival was higher following surgical treatment (87.1 vs. 45–57 %). There was no statistically significant difference in local recurrence in patients treated with SABR compared with surgery (3.5–14.5 vs. 4.8–20 %).

According to another recently published review [29], surgery remains the treatment of choice for patients with operable early stage NSCLC, since there is insufficient evidence to establish that SBRT is equivalent to surgery. Among the recommendations, the authors state that for medically operable patients with stage T1-2 N0M0 NSCLC, surgery remains the standard treatment due to the lack of high-quality comparative analysis. However, for medically inoperable patients or those with stage T1-2N0M0 NSCLC refusing surgery, SBRT should be preferred.

Zang and colleagues [41••] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on six studies containing 864 matched patients. Surgical treatment was associated with a better long-term survival in patients with early stage NSCLC. However, the difference in 1- and 3-year cancer-specific survival, disease-free survival and local and distant control rates were not statistically different.

As we can see from different reviews, the available evidence is not enough to conclude that surgery (sub-lobar resection) can be replaced by SBRT in operable patients. On the contrary, it seems that in high-risk cases, similar or even better long-term survival can be achieved with SBRT. Unfortunately, conclusions from most published experiences and reviews are biased by case selection and technical confounders.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Currently, there is not enough evidence to recommend non-surgical treatment by SBRT in patients considered fit for VATS lobectomy and mediastinal lymph node dissection. In high-risk cases, SBRT is a good option compared to wedge resection, but anatomical segmentectomy plus mediastinal lymphadenectomy can be an option to be discussed at MDT meetings. If SBRT is considered indicated, complete mediastinal staging by image techniques (FDG-PET/CT) plus fine-needle mediastinal lymph node puncture guided by endosonography (EUS and EBUS) is a must in order to decrease the rate of mediastinal relapsing and allow for adjuvant chemotherapy when indicated.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:• Of importance •• Of major importance

Wright G, Manser RL, Byrnes G, Hart D, Campbell DA. Surgery for non-small cell lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Thorax. 2006;61:597–603.

•• Roach MC, Videtic GMM, JD Bradley. Treatment of peripheral non-small cell lung carcinoma with stereotactic body radiation therapy. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:1261–7 This is a well-documented short review giving a complete view of technical and clinical concepts on SBRT and also commenting on the best available papers dealing with SBRT for early peripheral NSCLC.

Chang JY, Senan S, Marinus PA, Mehran RJ, Louie AV, Balter P, Groen HJM, Mc Rae SE, Widder J, Feng L, van der Borne BEEM, Munsell MF, Hurkmans C, Berry DA, van Werkhoven E, Kresl JJ, Dingemans AM, Dawood O, Haasbeek CJA, Carpenter LS, De Jaeger K, Komaki R, Slotman BJ, Smit EF, Roth JA. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus lobectomy for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:630–7.

Zhong C, Fang W, Mao T, Yao F, Chen W, Hu D. Comparison of thoracoscopic segmentectomy and thoracoscopic lobectomy for small-sized stage IA lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:362–7.

Harada H, Okada M, Sakamoto T, Matsuoka H, Tsubota N. Functional advantage after radical segmentectomy versus lobectomy for lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:2041–5.

Whitson BA, Groth SS, Andrade RS, Maddaus MA, Habermann EB, D’Cunha J. Survival after lobectomy versus segmentectomy for stage i non-small cell lung cancer: a population-based analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1943–50.

Rami-Porta R, Tsuboi M. Sublobar resection for lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:426–35.

Verstegen NE, Oosterhuis JW, Palma DA, Rodrigues G, Lagerwaard FJ, van der Elst A, Mollema R, van Tets WF, Warner A, Joosten JJ, Amir MI, Haasbeek CJ, Smit EF, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Stage I-II non-small-cell lung cancer treated using either stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) or lobectomy by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS): outcomes of a propensity score-matched analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1543–8.

Ricardi U, Frezza G, Filippi AR, Badellino S, Levis M, Navarria P, Salvi F, Marcenaro M, Trovò M, Guarneri A, Corvò R, Scorsetti M. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for stage I histologically proven non-small cell lung cancer: an Italian multicenter observational study. Lung Cancer. 2014;84:248–53.

Brunelli A, Kim AW, Berger KI, Addrizzo-Harris DJ. Physiologic Evaluation Of The Patient With Lung Cancer Being Considered For Resectional Surgery. Chest. 2013;143(5_suppl):e166S–90S.

Powell HA, Baldwin DR. Multidisciplinary team management in thoracic oncology: more than just a concept? Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1776–86.

Novoa N, Jiménez MF, Aranda JL, Rodriguez M, Ramos J, Gómez-Hernández MT, Varela G. Effect of implementing the European guidelines for functional evaluation before lung resection on cardiorespiratory morbidity and 30-day mortality in lung cancer patients: a case–control study of a matched series of patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;45:e89–93.

Varela G, Jiménez MF, Novoa N, Aranda JL. Agreement between type of lung resection planned and resection subsequently performed on lung cancer patients. Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41:84–7.

Eriguchi T, Takeda A, Sanuki N, Nishimura S, Takagawa Y, Enomoto T, Saeki N, Yashiro K, Mizuno T, Aoki Y, Oku Y, Yokosuka T, Shigematsu N. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for T3 and T4N0M0 non-small cell lung cancer. J Radiat Res. 2016;57:265–72.

Obiols C, Call S, Rami-Porta R, Trujillo-Reyes JC, Saumench R, Iglesias M, Serra-Mitjans M, Gonzalez-Pont G, Belda-Sanchís J. Survival of patients with unsuspected pN2 non-small cell lung cancer after an accurate preoperative mediastinal staging. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:957–64.

Lim E, McElnay PJ, Rocco G, Brunelly A, Massard G, Toker A, Passlick B, Varela G, Weder W. Invasive mediastinal staging is irrelevant for PET/CT positive N2 lung cancer if the primary tumour and ipsilateral lymph nodes are resectable. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:e32–3.

McElnay PJ, Choong A, Jordan E, Song F, Lim E. Outcome of surgery versus radiotherapy after induction treatment in patients with N2 disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Thorax. 2015;70:764–8.

Rocco G, Nason K, Brunelli A, Varela G, Waddell T, Jones DR. Management of stage IIIA (N2) non-small cell lung cancer: a transatlantic perspective. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:1247–50.

Onishi H, Shirato H, Nagata Y, Hiraoka M, Fujino M, Gomi K, Karasawa K, Niibe Y, Takai Y, Kimura T, Takeda A, Ouchi A, Hareyama M, Kokubo M, Kozuka T, Arimoto T, Hara R, Itami J, Araki T. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: can SBRT be comparable to surgery? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:13.

Lagerwaard FJ, Verstegen NE, Haasbeek CJ, Slotman BJ, Paul MA, Smit EF, Senan S. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy in patients with potentially operable stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:348–53.

Lardinois D, De Leyn P, Van Schil P, Porta RR, Waller D, Passlick B, Zielinski M, Lerut T, Weder W. ESTS guidelines for intraoperative lymph node staging in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:787–92.

Yang CF, Kumar A, Gulack BC, Mulvihill MS, Hartwig MG, Wang X, D’Amico TA, Berry MF. Long-term outcomes after lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer when unsuspected pN2 disease is found: a National Cancer Data Base analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1380–8.

Kaseda K, Watanabe K, Asakura K, Kazama A, Ozawa Y. Identification of false-negative and false-positive diagnoses of lymph node metastases in non-small cell lung cancer patients staged by integrated 18F- fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography: a retrospective cohort study: NSCLC lymph node staging via PET/CT. Thoracic Cancer. 2016;7:473–80.

De Leyn P, Dooms C, Kuzdzal J, Lardinois D, Passlick B, Rami-Porta R, Turna A, Van Schil P, Venuta F, Waller D, Weder W, Zielinski M. Revised ESTS guidelines for preoperative mediastinal lymph node staging for non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;45:787–98.

Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Eloubeidi MA, Frederick PA, Minnich DJ, Harbour KC, Dransfield MT. The true false negative rates of esophageal and endobronchial ultrasound in the staging of mediastinal lymph nodes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:427–34.

Akthar AS, Ferguson MK, Koshy M, Vigneswaran WT, Malik R. Limitations of PET/CT in the detection of occult N1 metastasis in clinical stage I (T1-2aN0) non-small cell lung cancer for staging prior to stereotactic body radiotherapy. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2016;. doi:10.1177/1533034615624045.

European Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database Committee. Silver book. http://www.ests.org/_userfiles/pages/files/ESTS%202016Silver_Book_FULL_FINAL_14.50.pdf. Accessed 07 July 2016.

•• Kang KH, Okoye CC, Patel RB, Siva S, Biswas T, Ellis RJ, Yao M, Machtay M, Lo SS. Complications from Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Lung Cancer. Cancers(Basel) 2015;7:981–1004. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this publication is reporting the most complete review on the prevalence and possible causes of complications after SBRT.

Boily G, Filion E, Rakovich G, Kopek N, Tremblay L, Samson B, Goulet S, Roy I. Comité de l’evolution des pratiques en oncologie. Stereotactic ablative radiation therapy for the treatment of early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: CEPO review and recommendations. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:872–82.

Dunlap NE, Cai J, Biedermann GB, Benedict SH, Sheng K, Schefler TE, Kavanagh BD, Lamer JM. Chest wall volume receiving >30 Gy predicts risk of severe pain and/or rib fracture after lung stereotactic body radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:796–801.

Kim SS, Song SY, Kwak J, Ahn SD, Kim JH, Lee JS, Kim WS, Kim SW, Choi EK. Clinical prognostic factors and grading system for rib fracture following stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) in patients with peripheral lung tumors. Lung Cancer. 2013;79:161–6.

Yamashita H, Takahashi W, Haga A, Nakagawa K. Radiation pneumonitis after stereotactic radiation therapy for lung cancer. World J Radiol. 2014;6:708–15.

Timmerman R, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, Papiez L, Tudor K, DeLuca J, Ewing M, Abdulrahman R, DesRosiers C, Williams M, Fletcher J. Excessive toxicity when treating central tumors in a phase II study of stereotactic body radiation therapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4833–9.

Agarwal R, Saluja P, Pham A, Ledbetter K, Bains S, Varghese S, Clements J, Kim YH. The effect of CyberKnife therapy on pulmonary function tests used for treating non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective, observational cohort pilot study. Cancer Manag Res. 2012;4:347–50.

Kevin L, Stephans KL, Djemil T, Reddy CA, Gajdos SM, Kolar M, Machuzak M, Mazzone P, Videtic GMM. Comprehensive analysis of pulmonary function Test (PFT) changes after stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for stage I lung cancer in medically inoperable patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:838–44.

National Cancer Institute: Common Toxicity Criteria Version 2.0. Bethesda, MD, US National Institutes of Health, 1999.

Varela G, Gómez-Hernández MT. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for early stage non-small cell lung cancer: a word of caution. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5:102–5.

Matsuo Y, Chen F, Hamaji M, Kawaguchi A, Ueki N, Nagata Y, Sonobe M, Morita S, Date H, Hiraoka M. Comparison of long-term survival outcomes between stereotactic body radiotherapy and sublobar resection for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer in patients at high risk for lobectomy: A propensity score matching analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:2932–8.

Port JL, Parashar B, Osakwe N, Nasar A, Lee PC, Paul S, Stiles BM, Altorki NK. A propensity-matched analysis of wedge resection and stereotactic body radiotherapy for early stage lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(4):1152–9.

•• Mahmood S, Bilal H, Faivre-Finn C, Shah R. Is stereotactic ablative radiotherapy equivalent to sublobar resection in high-risk surgical patients with stage I non-small-cell lung cancer? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;17:845–53. The reader can find in this systematic review some useful data applicable for decision making in patients with compromised pulmonary function. The authors found no differences in local recurrence rates although overall survival is slightly longer in surgically treated patients.

•• Zhang B, Zhu F, Ma X, Tian Y, Cao D, Luo S, Xuan Y, Liu L, Wei Y. Matched-pair comparisons of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) versus surgery for the treatment of early stage non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol 2014;112:250–5. This systematic review found a superior 3-year OS after surgery compared with SBRT, which supports the need to compare both treatments in large prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trials.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Jimenez, Novoa, and Varela declare no conflict of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical collection on Thoracic Surgery.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jimenez, M.F., Novoa, N.M. & Varela, G. Surgery Versus Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Resectable Lung Cancer. Curr Surg Rep 4, 40 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40137-016-0162-1

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40137-016-0162-1