Abstract

Purpose of Review

Infections of the salivary glands (infectious sialadenitis) can be caused by many different pathogens. We intend to review the types of infections, their presentation and treatment, and the potential associated risks.

Recent Findings

Bacterial sialadenitis is attributed to retrograde oral contamination and is associated with duct obstruction and diminished salivary flow. Treatment is supportive with antibiotic therapy and monitoring for rare complications from infection. Many viruses can be implicated in parotitis, most notably mumps paramyxovirus, and are treated symptomatically. Other infections, such as actinomyces and mycobacterium, can be a rare cause of infectious sialadenitis.

Summary

For patients presenting with the signs and symptoms of infectious sialadenitis, careful history, exam and workup can direct therapy. Patients should be monitored for potential complications associated with persistent infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Infectious sialadenitis can be caused by a variety of microorganisms including viruses, bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi. A careful history and physical examination often afford clues to the etiology of the inflammation. Symptomatology, acuity, pattern of gland involvement, palpable fluctuance, expression of purulence from the salivary duct, and comorbid conditions are all useful pieces of information. Further workup may include ultrasound or CT scan, labs, and FNA or biopsy.

The parotid glands are affected by non-obstructive infectious sialadenitis at higher rates than the submandibular glands [1]. The serous nature of parotid saliva is suspected to be less bacteriostatic compared to the mucinous submandibular gland secretions [2].

Bacteria

Bacterial sialadenitis is an acute process characterized by a sudden onset of pain and swelling in the affected gland. Physical exam usually reveals a single, tender, indurated gland that may produce purulent secretions at the duct orifice when massaged (Fig. 1). In 1931, Berndt et al. determined that retrograde flow of oral bacteria through the salivary duct is the cause of acute bacterial sialadenitis; this is still felt to be the case today [3]. Dehydration and processes that impede or inhibit salivary flow, such as radiation, stricture, or blockage, thus predispose the patient to bacterial sialadenitis [4].

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative pathogen in adults, found in 50–90% of cases [5]. Streptococcus and H. influenzae are also relatively common, and gram-negative bacilli (including E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella spp., and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) have also been reported rarely. Anaerobes such as Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, and Prevotella species may be involved in a significant number of cases as well [6, 7]. In a review of 35 cases of neonatal bacterial sialadenitis, S. aureus remained the most likely cause, with other gram-positive cocci and then gram-negative bacilli following, though at higher rates than in adults [8].

Of note, bacteria that enter salivary glands through retrograde migration do not necessarily cause acute sialadenitis and may be more common than generally understood. Electron microscopy of sialoliths has shown bacterial biofilms within the mineralized framework [9•]. Thus, bacterial entry into salivary glands is likely responsible not only for acute suppurative sialadenitis, but may contribute to obstructive sialadenitis and sialoliths as well.

Complications of acute bacterial sialadenitis are rare. The most common is the intraglandular abscess formation. The infection may also spread beyond the parotid gland and cause sepsis or osteomyelitis, necessitating more extensive treatment. Acute sialadenitis does not generally affect the facial nerve; however, there are isolated reports of temporary facial paralysis with abscess formation [10]. Facial paralysis should prompt a search for a parotid malignancy as an underlying cause of obstruction.

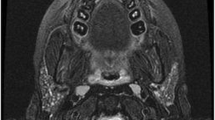

Diagnosis is typically clinical. Imaging can be used to confirm the diagnosis and rule out complications. Ultrasound of glands affected by acute bacterial sialadenitis shows diffuse, heterogenous enlargement [11•]. If an abscess is present, it can be distinguished as an irregular hypoechoic area. On contrast-enhanced CT, acute sialadenitis shows as an enlarged hyper-enhancing gland, possibly with internal hypodense edema and surrounding fat stranding. Abscesses are seen as rim-enhancing structures with central hypodensity within the gland [12] (Fig. 2).

Adequate treatment of acute bacterial sialadenitis relies on directed antibiotic treatment and should also address salivary stasis or underproduction. Empiric antibiotic therapy should consist of broad-spectrum agents that cover both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. If the patient has known MRSA colonization, or has been in a health care setting, additional MRSA coverage should be added [13]. If purulence at the duct orifice is present, cultures can be taken to direct antibiotic therapy. Oral or IV hydration, gland massage and warm compresses, and sialogogues are useful adjuncts to increase salivary flow. Abscesses should be addressed through imaging-guided aspiration or surgical incision and drainage. Correcting the underlying issue that predisposes the patient to salivary stasis is useful in preventing future infections.

Viruses

Viral Mumps

The mumps virus is a paramyxovirus, transmitted by direct contact or droplet spread, which causes mumps, also known as parotitis epidemica. Clinical mumps is defined as “acute onset of unilateral or bilateral tender, self-limiting swelling of the parotid or other salivary glands, lasting 2 or more days without other apparent cause” [14]. Although 30–40% of mumps viral infections can be asymptomatic, 95% of patients with symptoms develop parotitis [15]. This parotitis is typically bilateral and painful, lasting for about 1 week. Other symptoms of mumps include orchitis, which is bilateral in about a quarter of cases; oophoritis; spontaneous abortion of first trimester pregnancies; meningitis; pancreatitis; and rarely encephalitis [15, 16•].

Mumps should be suspected in any patient with typical clinical manifestations, especially if exposure to the virus is known to have occurred. Although unvaccinated individuals are at the highest risk of infection, vaccinated individuals are also at risk, as the effectiveness of the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) two-dose series is 83–88% [16•, 17]. If mumps is suspected, a buccal swab should be obtained for RT-PCR of the viral RNA and possible viral culture, and serum sample for IgM and acute-phase IgG testing and serum RT-PCR [18].

Treatment consists of supportive care. This may include typical symptom management for parotitis, such as analgesics and warm compresses. Antipyretics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications may also be useful.

Other Viral Etiologies

Multiple viruses can cause sialadenitis mimicking mumps. Symptoms of non-mumps viral sialadenitis are typically unilateral parotid gland swelling, sometimes associated with fever and sore throat [19]. Multiple studies of acute, viral non-mumps parotitis demonstrate that Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), parainfluenza virus (PIV), and adenovirus are the most likely causes; however, estimations of rate of infections vary. A study of Finnish children with parotitis who had previously been vaccinated for mumps found that 7% had EBV; a Barcelona study of children who tested negative for mumps found that over half had EBV; and in Italy, EBV was the causative factor in 20% of mumps-negative cases [20,21,22]. Additionally, recent work in the USA has shown that influenza A and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6) may be a significant contributor to non-mumps parotitis during the influenza season [19]. Influenza A, cytomegalovirus (CMV), coxsackie A and B, and hepatitis C have also been reported to be associated with submandibular sialadenitis and swelling [23, 24].

Viruses may cause salivary gland swelling due to other etiologies than mumps-like parotitis. HIV may cause a diffuse gradual enlargement of the parotid glands, which is termed HIV-associated salivary gland disease [25]. More commonly, however, HIV is associated with development of benign lymphoepithelial cysts (BLEC). BLEC are found primarily in the parotid glands, likely due to the intraparotid lymph nodes where HIV may reside. They are typically bilateral, may develop multiple cysts, and can grow to be quite large [2]. BLEC in the HIV-negative patient is so rare that any patient who has bilateral cystic parotid swelling of unknown etiology should undergo HIV testing [26]. Management of BLEC should include antiretroviral therapy for underlying disease control, but may also include repeated aspirations, sclerosing therapy, surgical excision, or radiation to the site [27]. A 24-Gy of radiation has been recommended for long-term control [28]. HIV may also cause general swelling of salivary glands without BLEC, and in the parotid gland, this has been classified into patterns including lymphocytic aggregations, fatty infiltration, and lymphadenopathy. Both BLEC and other patterns of HIV-associated sialadenitis tend to be chronic and painless [2].

Hepatitis C can cause a Sjogren-like sicca syndrome, which may cause enlargement of salivary glands [29]. There is little evidence that hepatitis C directly infects salivary tissue.

Actinomycosis

Actinomycosis is an infection caused by one of the species of Actinomycetes, which are branching, anaerobic, gram-positive bacteria that are part of the normal oral flora [30]. Although actinomycosis is bacterial in nature, the natural history of the disease is significantly different from bacterial sialadenitis and thus is reported separately here. Actinomyces species take advantage of oral mucosal injury or dental infection to invade tissues in the head and neck without respect to anatomic barriers or fascial planes [31]. Thus, it is suggested that parotid actinomycosis is truly a primary masticator space infection with extension from an oral source [32], although a few cases have been more consistent with spread via the parotid duct [33]. Actinomycosis often results in fistulae or sinus tracts forming in the area of infection. Diagnosis can be made by fine-needle aspiration of the mass, with finding characteristic “sulfur granules” (named for the yellow color, as no sulfur is present) on histology [30]. Treatment is a prolonged course of high-dose penicillin, though it is susceptible to multiple other antibiotics, and possible surgical excision of a well-defined lesion [34].

Other Infections

Mycobacterial infections of the salivary glands can be caused by M. tuberculosis or by atypical mycobacteria (nontuberculous mycobacteria). Although direct infection of the salivary tissue is possible, it is much more common for the infection to affect periglandular or intraglandular lymph nodes [35]. Tuberculous parotitis is rare even in locations where tuberculosis is endemic. It is possible for tuberculosis to directly involve parotid parenchyma due to hematologic or lymphatic spread from the lung, or from direct spread from the oral cavity. In a review of 49 cases of TB parotitis in 2005, 15 of which had detailed description of the histopathology pattern, 47% had intraparotid lymph node involvement, 33% had gland parenchyma involvement, and 20% had both [36]. Tuberculous parotitis can cause either an acute sialadenitis with diffuse gland enlargement or a chronic slowly growing defined lesion within the gland, the more common form of the disease [37]. Immunocompromised patients are more likely to have an aggressive course of disease and may develop complications including facial paralysis or a fistula [38, 39]. The duration of antituberculosis medical therapy may last from 6 to 10 months [36].

Other pathogens that result in granulomatous lymphadenitis can similarly affect the salivary glands via extension from intraglandular or periglandular nodes. These include cat-scratch disease (Bartonella henselae), toxoplasmosis (the protozoan T. gondii), and tularemia (Francisella tularensis) [2]. Diagnosis of these entities can be difficult and requires careful history taking to evaluate for exposures consistent with each disease, and positive serum titers (for B. henselae) or isolation of the organism (for T. gondii). Once diagnosed, appropriate antibiotic therapy is all that is required for treatment.

Conclusion

Infectious sialadenitis encompasses a broad range of disease presentations and causative organisms. The salivary gland enlargement may be acute or chronic, diffuse or focal, disseminated or targeted, and potentially related to a host of other comorbidities. Despite this, a careful evaluation can significantly narrow down the list of possible causes. Recognition of this diversity of etiologies is helpful in appropriately managing infectious sialadenitis.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

McQuone SJ. Acute viral and bacterial infections of the salivary glands. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 1999;32:793–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70173-0.

Malloy KM, Rosen D, Rosen MR. Sialadenitis. In: Witt RL, editor. Salivary gland diseases: surgical and medical management. 1st ed. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag; 2006. https://doi.org/10.1055/b-002-66270.

Berndt A, Buck R, von Buxton R. The pathogenesis of acute suppurative parotitis: an experimental study. Am J Med Sci. 1931;182:639–49.

Wilson KF, Meier JD, Ward PD. Salivary gland disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:882–8 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25077394.

Brook I. The bacteriology of salivary gland infections. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2009;21:269–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coms.2009.05.001.

Brook I. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of suppurative sialadenitis. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:526–9.

Brook I, Frazier EH, Thompson DH. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of acute suppurative parotitis. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:170–2. https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-199102000-00012.

Spiegel R, Miron D, Sakran W, Horovitz Y. Acute neonatal suppurative parotitis: case reports and review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:76–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000105181.74169.16.

• Kao WK, Chole RA, Ogden MA. Evidence of a microbial etiology for sialoliths. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:69–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.27860Findings from this study suggest that sialoliths form around a core of biofilm caves and may arise from immune response to ductal injury caused by bacterial biofilms.

Hajiioannou JK, Florou V, Kousoulis P, Kretzas D, Moshovakis E. Reversible facial nerve palsy due to parotid abscess. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:1021–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.08.016.

• Knopf A. Sonography of major salivary glands. In: Welkoborsky H, Jecker P, editors. Ultrasonography of the head and neck. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 235–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12641-4_11. This review of ultrasound findings in various etiologies of salivary gland inflammation contains good reference images and descriptions.

Cunqueiro A, Gomes WA, Lee P, Dym RJ, Scheinfeld MH. CT of the neck: image analysis and reporting in the emergency setting. Radiographics. 2019;39:1760–81. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2019190012.

Goyal N, Deschler DG. Bacterial Sialadenitis. In: Durand M, Deschler D, editors. Infections of the ears, nose, throat, and sinuses. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 291–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74835-1_24.

Hatchette TF, Mahony JB, Chong S, LeBlanc JJ. Difficulty with mumps diagnosis: what is the contribution of mumps mimickers? J Clin Virol. 2009;46:381–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2009.09.024.

Hviid A, Rubin S, Mühlemann K. Mumps. Lancet. 2008;371:932–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60419-5.

• Lam E, Rosen JB, Zucker JR. Mumps: an Update on Outbreaks, Vaccine Efficacy, and Genomic Diversity. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020;33. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00151-19This is a useful review of mumps and the vaccine series to prevent it, as well as up-to-date information on recent outbreaks and mitigation strategies.

Demicheli V, Rivetti A, Debalini MG, Di Pietrantonj C. Vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub3.

Mumps: Questions and Answers about Lab Testing. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. http://www.cdc.gov/mumps/lab/qa-lab-test-infect.html#st3.

Elbadawi LI, Talley P, Rolfes MA, Millman AJ, Reisdorf E, Kramer NA, et al. Non-mumps viral parotitis during the 2014–2015 influenza season in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:493–501. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy137.

Davidkin I, Jokinen S, Paananen A, Leinikki P, Peltola H. Etiology of mumps-like illnesses in children and adolescents vaccinated for measles, mumps, and rubella. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:719–23. https://doi.org/10.1086/427338.

Barrabeig I, Costa J, Rovira A, Marcos MA, Isanta R, López-Adalid R, et al. Viral etiology of mumps-like illnesses in suspected mumps cases reported in Catalonia, Spain. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:282–7. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.36165.

Magurano F, Baggieri M, Marchi A, Bucci P, Rezza G, Nicoletti L. Mumps clinical diagnostic uncertainty. Eur J Pub Health. 2018;28:119–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx067.

Ikenori M, Shoji K, Matsui T, Ishiguro A, Kono N, Miyairi I. A pediatric case of acute neck swelling due to bilateral submandibular sialadenitis following influenza A infection. IDCases. 2019;15:e00517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2019.e00517.

Fujiwara SA, Kobayashi T, Ikeda R, Yasuda K, Kubota I, Takeishi Y. Bilateral submandibular sialadenitis following influenza A virus infection. IDCases. 2017;10:49–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2017.08.016.

Sanan A, Cognetti DM. Rare parotid gland diseases. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2016;49:489–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2015.10.009.

Pillai S. Benign lymphoepithelial cyst of the parotid in HIV negative patient. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:MD05–6. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/17915.7609.

Sekikawa Y, Hongo I. HIV-associated benign lymphoepithelial cysts of the parotid glands confirmed by HIV-1 p24 antigen immunostaining. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;Published:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-221869.

Mourad WF, Young R, Kabarriti R, Blakaj DM, Shourbaji RA, Glanzman J, et al. 25-year follow-up of HIV-positive patients with benign lymphoepithelial cysts of the parotid glands: a retrospective review. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:4927–32 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24222131.

Haddad J, Trinchet J-C, Pateron D, Mal F, Beaugrand M, Munz-Gotheil C, et al. Lymphocytic sialadenitis of Sjögren’s syndrome associated with chronic hepatitis C virus liver disease. Lancet. 1992;339:321–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(92)91645-O.

Sharkawy AA, Chow AW. Cervicofacial actinomycosis. In: Post T, editor. UpToDate. Waltham, Massachusetts: UpToDate; 2020.

Belmont MJ, Behar PM, Wax MK. Atypical presentations of actinomycosis. Head Neck. 1999;21:264–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199905)21:3<264::AID-HED12>3.0.CO;2-Y.

Hensher R, Bowerman J. Actinomycosis of the parotid gland. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;23:128–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0266-4356(85)90063-4.

Sittitrai P, Srivanitchapoom C, Pattarasakulchai T, Lekawanavijit S. Actinomycosis presenting as a parotid tumor. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39:241–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2011.03.011.

Stewart AE, Palma JR, Amsberry JK. Cervicofacial actinomycosis. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2005;132:957–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2004.07.008.

Stanley RB, Fernandez JA, Peppard SB. Cervicofacial mycobacterial infections presenting as major salivary gland disease. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1271–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.1983.93.10.1271.

Lee I-K, Liu J-W. Tuberculous Parotitis: case report and literature review. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:547–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940511400710.

Gayathri B, Manjula K, Kalyani R. Primary tuberculous parotitis. J Cytol. 2011;28:144–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-9371.83479.

Yaniv E, Avedillo H. Facial paralysis due to primary tuberculosis of the parotid gland. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1985;9:195–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-5876(85)80021-5.

Suleiman AM. Tuberculous parotitis: report of 3 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:320–3. https://doi.org/10.1054/bjom.2001.0644.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

For the only cited study performed by one of this article’s authors (Kao et al., 2020), all procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional review board (IRB) of Washington University School of Medicine (IRB #201108332). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, all other studies cited in this article were performed in accordance with institutional and/or national ethical standards and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Salivary Gland Disorders

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lindburg, M., Ogden, M.A. Infectious Sialadenitis. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 9, 87–91 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-020-00315-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-020-00315-5