Abstract

Purpose

Migrants represent a considerable proportion of HIV diagnoses in Europe and are considered a group at risk of late presentation. This study examined the incidence of HIV diagnoses and the risk of late presentation according to migrant status, ethnic origin and duration of residence.

Methods

We conducted a historically prospective cohort study comprising all adult migrants to Denmark between 1.1.1993 and 31.12.2010 (n = 114.282), matched 1:6 to Danish born by age and sex. HIV diagnoses were retrieved from the National Surveillance Register and differences in incidence were assessed by Cox regression model. Differences in late presentation were assessed by logistic regression.

Results

Both refugees (HR = 5.61; 95% CI 4.45–7.07) and family-reunified immigrants (HR = 10.48; 95% CI 8.88–12.36) had higher incidence of HIV diagnoses compared with Danish born and the incidence remained high over time of residence for both groups. Migrants from all regions, except Western Asia and North Africa, had higher incidence than Danish born. Late presentation was more common among refugees (OR = 1.87; 95% CI 1.07–3.26) and family-reunified immigrants (OR = 2.30; 95% CI 1.49–3.55) compared with Danish born. Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa were the only regions with a higher risk of late presentation. Late presentation was only higher for refugees within 1 year of residence, whereas it remained higher within 10 years of residence for family-reunified immigrants.

Conclusions

This register-based study revealed a higher incidence of HIV diagnoses and late presentation among migrants compared with Danish born and the incidence remained surprisingly high over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The increasing global migration has made migrants’ health an important topic in Europe. In Denmark, immigrants (8.9%) and their descendants (2.7%) constituted 11.6% of the population on 1 January 2015, whereof 58% originated from non-western countries [1]. Meeting the health needs of migrants in immigration countries is a major challenge, as they may differ in disease profiles and risk factors from the native population, but also because they may experience barriers to accessing health services in the recipient countries [2, 3].

It is estimated that globally 36.7 million people were living with HIV/AIDS in 2015, most of them in Sub-Saharan Africa [4]. The HIV epidemic continues to be a public health issue in Europe and migrants are considered a key group at risk for HIV infection as they represent a considerable proportion of new HIV diagnoses in Europe [5]. Despite a decrease over time across Europe, a high proportion of HIV cases continue to be diagnosed at a late stage of their infection [6]. In Denmark, it is estimated that 47% of all individuals diagnosed with HIV in 2016 were late presenters [7]. Late presentation has consequences both for the individual, in terms of poor treatment outcomes and increased morbidity and mortality [6, 8], and for the general public health in terms of risk of transmission from individuals unaware of their HIV infection and increased healthcare costs [9, 10]. Migrants constitute a fragile population and often lack proper access to health care facilities both in the country of origin and during the migration, but also in the immigration country [11], and they are, therefore, considered a group at risk of late presentation [12, 13]. In Europe, migrants from low- and middle-income regions have a higher risk of late presentation compared with native populations [14]. However, previous studies have mainly focused on ‘region of origin’ as the determinant and, to our knowledge, no studies have addressed the importance of migrant status (refugees vs. family reunified) and duration of residence.

The aim of this study was, therefore, to assess the incidence of HIV diagnoses and the risk of late presentation among migrants compared with Danish born and to examine the effect of both migrant status, region of origin and duration of residence.

Materials and methods

Study population

This historical prospective cohort is based on data obtained through the Danish Immigration Service. The cohort includes all family-reunified immigrants and refugees aged ≥18 years who obtained residency in Denmark from 1 January 1993 to 31 December 2010. A total of 114 331 migrants comprised the cohort. The cohort and exclusion processes have previously been described in more detail [15]. The migrants were divided into five groups based on the residence permit: (i) asylum seekers, (ii) quota refugees, (iii) family reunified to refugees, (iv) family reunified to immigrants and (v) family reunified to Danish/Nordic citizens.

Statistics Denmark identified a Danish-born comparison group through an individual 1:6 matching on age and sex on the first day of the year in which the migrant was granted residency in Denmark. To exclude descendants from the comparison group, only Danish-born individuals born from Danish parents were included. In the present study, we excluded 18 refugees and 31 family-reunified immigrants due to date of HIV diagnosis between the date of arrival in Denmark and the date of residency, which because of the matching with the Danish-born comparison group happening at this date, was the start of follow-up. Furthermore, 58 Danish born were excluded due to date of HIV diagnosis before start of follow-up. This left 114 282 migrants (43 974 refugees and 70 308 family-reunified immigrants) and 686 505 Danish born in the final cohort.

Data collection

Personal identification numbers of individuals in the cohort were cross-linked to the Danish National Surveillance Register (NSR) at the Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at Statens Serum Institut. NSR contains national data on all mandatory notifications of infectious diseases. According to Danish law, newly diagnosed HIV infection is a notifiable disease and the treating physician submits the notification to NSR. Subsequently, all individuals in the cohort diagnosed with AIDS between 1 January 1993 and 31 July 2015 and HIV between 1 January 2005 and 31 July 2015 were identified. HIV cases were classified according to the European consensus definition, which defined late presentation as a diagnosis with a CD4 count < 350 cells/µL or clinical aids, regardless of the CD4 count. Advanced HIV disease was defined as a diagnosis with a CD4 count < 200 cells/µL or with clinical aids, regardless of the CD4 count [16]. The group, who presented late according to this definition, included a potential number of individuals with low CD4 count due to primary HIV infection. To ascertain that no individuals with primary HIV infection were categorized as late presenters, we classified patients with known primary HIV infection at time of presentation as non-late presenters regardless of the CD4 count.

In the analysis of late presentation and advanced HIV disease, we only included persons: (a) diagnosed with clinical aids; or (b) diagnosed with HIV infection with available information on CD4 count. Individuals with missing information on CD4 count were excluded (N = 117). This left 567 persons eligible for analysis of late presentation.

In accordance with the United Nations Standard Country and Area CODE Classifications [17], individuals were divided into sixth geographical regions of origin. Duration of residence was calculated from the date of receiving residency until the date of diagnosis. Date of death or emigration was obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System. Data on annual personal income were obtained from Statistics Denmark, as a proxy for socioeconomic position to adjust for its potential effect on differences between migrants and Danish born. The variable is updated annually on 31 December and was calculated as an average income beginning 1 year after arrival until 1 year before diagnosis.

Statistical analyses

We estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of incidence of HIV diagnoses using a Cox regression model. HRs were calculated separately for migrant status and region of origin using Danish born as the reference group and adjusted for the matching variables, sex and age, and income. Entry into the study was the date of residency (for Danish born, the date of their migrant match). Individuals were followed until the first of the following events: (a) diagnosis, (b) first emigration, (c) death or (d) end of study (31 July 2015). The analysis of the impact of duration of residence was performed within migrant groups and using Danish born as the reference group and stratified by intervals of time from residency until diagnosis.

We calculated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals of late presentation using a logistic regression. Analyses were conducted separately for migrant status and region of origin, adjusted for age, sex and income. Again, the analysis of the impact of duration of residence was performed within migrant groups using Danish born as the reference group and stratified by intervals of time from residency until diagnosis. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Since participants diagnosed before 2005 all were diagnosed with AIDS and thereby per definition LP, including these in the analysis could lead to a possible overestimation of LP. A sensitivity analysis excluding participants with a diagnosis before 2005 from the analysis of LP was, therefore, performed.

Results

Incidence of HIV diagnoses

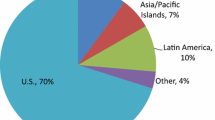

In total, 684 HIV diagnoses were reported, of which 405 were migrants and 279 Danish born. The proportion of HIV diagnoses among Danish born was higher than in the general Danish population. This is due to the age and sex distribution in the Danish-born group, which because of the matching procedure are different than the distribution in the general Danish population with participants in the cohort being younger and more likely to be male than in the general Danish population. The Danish-born controls are, therefore, not representative for the general Danish population. Study participants were on average followed for 14.2 years (SD 5.48), and participants with HIV were on average followed for 7.0 years (SD 5.52). Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics of individuals with HIV infection. The majority of the HIV infected migrants came from Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. Among family-reunified immigrants, the majority were family reunified to a Danish/Nordic citizen. The majority of migrants were infected abroad, whereas the majority of the Danish born were infected in Denmark. Table 2 shows HRs for HIV diagnoses by migrant status and region of origin. Compared with Danish born, the adjusted HRs were higher for both refugees (HR = 5.61; 95% CI 4.45–7.07) and family-reunified immigrants (HR = 10.48; 95% CI 8.88–12.36). Among refugees, the HRs were markedly higher for quota refugees (HR = 21.77; 95%16.21–29.23), compared with Danish born. Among family-reunified immigrants, the HRs were most marked for family-reunified immigrants to Danish/Nordic citizen (HR = 13.33; 95% CI 11.23–15.82), compared with Danish born. Variations were further seen according to region of origin, where migrants from all regions, except Western Asia and North Africa, all had higher incidence than Danish born. Sub-Saharan Africa (HR = 35.17; 95% CI 29.38–42.10), Latin America (HR = 14.89; 95% CI 9.54–23.25) and Southeast Asia (HR = 10.05; 95% CI 8.06–12.54) were the regions with the highest risk. Table 3 shows the effect of duration of residence on the incidence of HIV diagnoses for migrants compared with Danish born. For both refugees and family-reunified immigrants, the incidence remained higher over time of residence compared with Danish born.

Late presentation

In total, 306 (54%) of the HIV cases were late presenters, of which 135 were based on an AIDS diagnosis and 171 due to a CD4 count < 350. Late presentation was more common among refugees (58.7%) and family-reunified immigrants (64.4%) than for Danish born (41.9%). Table 4 shows ORs for late presentation and advanced HIV disease by migrant status and region of origin. Compared with Danish born, both refugees (OR = 1.87; 95% CI 1.07–3.26) and family-reunified immigrants (OR = 2.30; 95% CI 1.49–3.55) had higher risk of late presentation. Among family-reunified immigrants, only family-reunified immigrants to Danish/Nordic citizen had a higher risk of late presentation (OR = 2.35; 95% CI 1.51–3.68), compared with Danish born. The risk of presenting with advanced HIV disease (CD4 count < 200) was only higher for family-reunified immigrants compared with Danish born (OR = 2.04; 95% CI 1.31–3.17). For region of origin, the results were more contrasting. The adjusted ORs for both late presentation and presenting with advanced HIV disease were only higher for individuals originating from Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, whereas there were no differences between the other regions and Danish born. Table 5 shows the effect of duration of residence on the risk of late presentation among migrants compared with Danish born. Refugees had higher risk of late presentation within the first year of residence, while family-reunified migrants had higher risk of late presentation within 10 years of residence compared with Danish born. However, stratifying the analysis by duration of residence resulted in small numbers of cases in the different groups with resulting wide confidence intervals and low precision of the estimated associations. Further analyses examined risk factors for late presentation among migrants and the most interesting finding was that being homosexual was associated with a decreased risk of late presentation compared with heterosexual migrants (results not shown). Additionally, restricting the analysis to individuals with a diagnosis after 2005 did not substantially alter the estimates for the risk of LP among refugees and family-reunified immigrants.

Discussion

We found the incidence of HIV diagnosis to be higher for most migrants both by region of origin and migrant status and interestingly, family-reunified immigrants had the highest incidence. The risk of HIV diagnosis remained higher over time for both refugees and family-reunified immigrants, compared to Danish born. Moreover, late presentation varied with both region of origin and migrant status, and both refugees and family-reunified immigrants had higher risk of late presentation compared with Danish born. Late presentation was only higher for refugees within the first year of residence, whereas it remained higher within 10 years of residence for family-reunified immigrants compared with Danish born.

Discussion of findings

Our results are supported by data on epidemiological patterns of HIV infection in Western Europe, where migrants from countries with generalised HIV epidemics, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa, constitute a significant part of HIV infections [8, 12, 18,19,20]. A recent study found that 38% of the HIV diagnoses reported in Europe between 2007 and 2012 were among migrants. In accordance with the results of the present study, the majority of migrants with HIV in this study were from Sub-Saharan Africa (53%), thereby reflecting the epidemic in this region [14]. Previous European studies have investigated region of origin as a risk factor for late presentation. These studies all found that being of foreign origin was associated with an increased risk of presenting late compared with the native populations [6, 21, 22]. Consistent with our results, a Danish study found that individuals of “non-Danish origin” had an increased risk of late presentation, compared with Danish born [23]. Studies from Sweden and Italy likewise support an increased risk of late presentation among migrants compared with local born [24, 25]. However, these studies have not illuminated the incidence over time like our study.

The findings, moreover, showed differences in late presentation between migrants and Danish-born individuals. Different interacting factors may play a role. The results may reflect a high proportion of late presentation among HIV cases in the countries of origin [26, 27], and some of the migrants may, therefore, be late presenters already at arrival in Denmark. However, family-reunified immigrants, who had lived in Denmark for up to 10 years when diagnosed still had an increased risk of late presentation compared with Danish born. Given that most migrants are infected already at arrival in Denmark [7], the high incidence and late presentation probably reflect differences in health-seeking behaviour and access to HIV testing between migrants and Danish born. Despite the heavy burden of HIV among migrants in Europe, HIV testing for these populations is hindered by different barriers, which might contribute to the high proportion of late presenters among migrants [12, 28,29,30]. These barriers include lack of knowledge about available services, low self-perceived risk, feeling of stigma and difficulties in communication in the provider–patient relationship. Some of these barriers relate to migrants’ socioeconomic vulnerability and are shared with other groups at risk, but some are unique to migrants and make them a particularly vulnerable group for late presentation.

Our study contributes to the existing literature by including the role of migrant status. Consequently, we found differences in the incidence of HIV diagnoses and in the risk of late presentation between refugees and family-reunified immigrants, which may be explained by differences in the reception of the different migrant groups. Refugees and family-reunified immigrants are introduced differently to the Danish health care system upon arrival, which may affect their health-seeking behaviour. The Danish Red Cross offers a voluntary health assessment of all new asylum seekers. However, infectious diseases are screened for only if the attendee reveals symptoms during the consultation and HIV testing is only offered on an unsystematic basis. Quota refugees in Denmark, except those who enter the country as urgent cases, must consent to a medical examination performed by the International Organisation for Migration in refugee camps abroad before they are offered residency [31,32,33]. The examination includes voluntary HIV testing which may explain the remarkably high incidence of HIV diagnosis among quota refugees within 1 year of residence. In contrast, family-reunified immigrants are not offered any health assessment or introduction to the Danish health care system upon arrival and they rely entirely on their family when establishing life in exile. Given that many migrants are infected with HIV already at arrival in Denmark, the higher incidence of HIV diagnosis and the increased risk of late presentation over time among family-reunified immigrants could reflect inadequate screenings practices for family-reunified immigrants. Notably, family-reunified immigrants to a Danish/Nordic citizen, who were mainly women from Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, had a markedly higher incidence of HIV diagnoses and a higher risk of late presentation compared with Danish born. The results, therefore, call for the importance of securing that all migrants get screened upon arrival and to facilitate contact to a general practitioner. In Europe, laws and practices regarding HIV testing of newly arrived migrants differ between countries. Although mandatory testing has been identified in some European countries, the UNHCR, WHO and UNAIDS oppose all forms of mandatory HIV testing since it violates the right to liberty and security of the person [34]. Voluntary HIV testing should, therefore, be offered on a systematic basis either directly upon arrival or in primary care. Voluntary counselling and testing in primary care could be considered an appropriate way to encourage early diagnosis of HIV among recent migrants. Further, expanding testing not only in clinical settings but also in community settings or mobile clinics could serve as a potential strategy to increase testing among some migrant groups. Our study stresses the importance of recognizing that the reception of migrant groups differ and screening strategies will have to differ accordingly, i.e. refugees are often easier to target as they initially live in centers, whereas family-reunified migrants are best targeted through primary care as they immediately settle with their family.

Methodological strengths and limitations

The study used the unique Danish possibilities of cross-linkage between different national registers and made it possible to base all measurements on individual data. Consequently, we were able to identify and follow a large cohort of migrants based on information from the Danish Immigration Service. Data on HIV infection were retrieved from the NSR, which is considered to have a 95% coverage rate of all HIV diagnoses in Denmark. In contrast to most other studies of late presentation, we were able to take into account a low CD4 count because of primary HIV infection and categorized these as non-late presenters, which afforded a more accurate picture of late presentation. However, information on primary HIV infection was only available for 54% of the individuals included in the analysis of late presentation.

Some limitations must be considered. First, the calculation of incidence was based on diagnoses in Denmark. However, we cannot exclude that some migrants may have been diagnosed before arrival in Denmark but it is impossible to obtain comprehensive data on this through routine surveillance in countries of origin. Similarly, it is not always possible to estimate if HIV acquisition occurs before or after migration. However, since a relatively high proportion of the migrants are late presenters, and the majority of migrants are notified as infected abroad, we assume that the majority of the migrants are infected before arrival. In addition, it has been estimated that post-migration HIV acquisition mainly affects migrant MSM [35], which only accounted for 16.3% of the infected migrants in the present study. Second, data on CD4 count, which are necessary for the definition of late presentation, were missing in 17% of the HIV cases. We chose to exclude these individuals from the analysis of late presentation. Third, we were unable to base the analyses on countries of birth due to a limited number of cases, and we were, therefore, required to categorize migrants into different regions of origin based on the UN guidelines, thereby ignoring the diversity between different countries within the same region. Finally, a possible selection bias should be considered. Some quota refugees are granted asylum in Denmark because they are ill and in need of immediate treatment. Therefore, we cannot rule out that this has affected our results and might contribute to the high incidence of HIV diagnoses among quota refugees. However, according to the Danish Immigration Service only a minor part of quota refugees are granted asylum because of illness [36].

Conclusion

This nationwide register-based cohort study based on a population of 114 331 migrants showed a higher incidence of HIV and late presentation among refugees and family-reunified immigrants living in Denmark compared with Danish born, which remained surprisingly high over time especially for family-reunified immigrants. With a growing flow of migrants to Europe much could be gained by increased voluntary screening at arrival and by providing information about the health care system for all newly arrived migrants. Our results indicate that it is important to acknowledge the heterogeneity of migrant populations, which requires tailored strategies to some groups and a need to enhance cultural competencies among health care providers and planners.

References

Statistics Denmark. Immigrants in denmark. Statistics Denmark, Copenhagen; 2015.

Norredam M, Nielsen SS, Krasnik A. Migrants’ utilization of somatic healthcare services in Europe—a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20:555–63.

Norredam M. Migrants’ access to healthcare. Dan Med Bull. 2011;58(10):B4339

WHO. HIV/AIDS Key facts [Internet]. [cited 2016 Oct 14]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/en/.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and. Control ECDC. Assessing the burden of key infectious diseases affecting migrant populations in the EU/EEA. Tech. Rep. 2014.

Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Sabin ML, d’Arminio Monforte A, Brockmeyer N, Casabona J, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for late presentation for HIV-positive persons in Europe: results from the collaboration of observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study (COHERE). PLoS Med. 2013;10.

Christiansen A, Cowan SHIV. 2016. EPI-News No. 36. [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Sep 28]. Available from: https://www.ssi.dk/English/News/EPI-NEWS/2017/No 36–2017.aspx.

Sobrino-Vegas P, Moreno S, Rubio R, Viciana P, Bernardino JI, Blanco JR, et al. Impact of late presentation of HIV infection on short-, mid- and long-term mortality and causes of death in a multicenter national cohort: 2004–2013. J Infect. 2016;72:587–96.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505.

Sabin CA, Smith CJ, Gumley H, Murphy G, Lampe FC, Phillips AN, et al. Late presenters in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2004;18:2145–51.

Spallek J, Zeeb H, Razum O. What do we have to know from migrants’ past exposures to understand their health status? a life course approach. Emerg Themes Epidemiol BioMed Central Ltd. 2011;8:6.

Alvarez-Del Arco D, Monge S, Azcoaga A, Rio I, Hernando V, Gonzalez C, et al. HIV testing and counselling for migrant populations living in high-income countries: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23:1039–45.

Schäfer G, Kreuels B, Schmiedel S, Hertling S, Hüfner A, Degen O, et al. High proportion of HIV late presenters at an academic tertiary care center in northern Germany confirms the results of several cohorts in Germany: time to put better HIV screening efforts on the national agenda? Infection. 44. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2016. pp. 347–52.

Hernando V, Alvárez-del Arco D, Alejos B, Monge S, Amato-Gauci AJ, Noori T, et al. HIV Infection in Migrant Populations in the European Union and European Economic Area in 2007–2012. JAIDS. 2015;70:204–11.

Norredam M, Agyemang C, Hoejbjerg Hansen OK, Petersen JH, Byberg S, Krasnik A, et al. Duration of residence and disease occurrence among refugees and family reunited immigrants: Test of the “healthy migrant effect” hypothesis. Trop Med Int Heal. 2014;19:958–67.

Antinori A, Coenen T, Costagiola D, Dedes N, Ellefson M, Gatell J, et al. Late presentation of HIV infection: a consensus definition. HIV Med. 2011;12:61–4.

Division UNS. Standard country and area codes classifications (M49). Available from: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/.

AM HFD. The changing face of the HIV epidemic in Western Europe: what are the implications for public health policies? Lancet. 2004;364:83–94.

Chadborn TR, Delpech VC, Sabin CA, Sinka K, Evans BG. The late diagnosis and consequent short-term mortality of HIV-infected heterosexuals. 2006;2000–4.

European Centre for Disease Prevention. and Control (ECDC). HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2014. 2015.

Op de Coul ELM, van Sighem A, Brinkman K, Benthem BH van, Ende ME van der, Geerlings S, et al. Factors associated with presenting late or with advanced HIV disease in the Netherlands, 1996–2014: results from a national observational cohort. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009688.

Hachfeld A, Ledergerber B, Darling K, Weber R, Calmy A, Battegay M, et al. Reasons for late presentation to HIV care in Switzerland. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:1–8.

Helleberg M, Engsig FN, Kronborg G, Laursen AL, Pedersen G, Larsen O, et al. Late presenters, repeated testing, and missed opportunities in a Danish nationwide HIV cohort. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44:282–8.

Brännström J, Svedhem Johansson V, Marrone G, Wendahl S, Yilmaz A, Blaxhult A, et al. Deficiencies in the health care system contribute to a high rate of late HIV diagnosis in Sweden. HIV Med. 2016;17:425–35.

Sulis G, El Hamad I, Fabiani M, Rusconi S, Maggiolo F, Guaraldi G, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of HIV/AIDS infection among migrants at first access to healthcare services as compared to Italian patients in Italy: a retrospective multicentre study, 2000–2010. Infection. 2014;42:859–67.

Hønge BL, Jespersen S, Aunsborg J, Mendes DV, Medina C, Té D da. S, et al. High prevalence and excess mortality of late presenters among HIV-1, HIV-2 and HIV-1/2 dually infected patients in Guinea-Bissau - A cohort study from West Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:1–13.

Jeong SJ, Italiano C, Chaiwarith R, Ng OT, Vanar S, Jiamsakul A, et al. Late Presentation into Care of HIV Disease and Its Associated Factors in Asia: Results of TAHOD. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2016;32:255–61.

Blondell SJ, Kitter B, Griffin MP, Durham J. Barriers and Facilitators to HIV Testing in Migrants in High-Income Countries: a systematic review. Aids Behav. 2015;19:2012–24.

Alberer M, Malinowski S, Sanftenberg L, Schelling J. Notifiable infectious diseases in refugees and asylum seekers: experience from a major reception center in Munich, Germany. Infection. 2018;46:375–83.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), WHO Regional Office for Europe. Migrant health: access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for migrant populations in EU/EEA countries. Stockholm, ECDC 2009; p 35.

Internation Organization for Migration (IOM). Assisting Quota Refugees for Resettlement to Denmark. 2006. Available from: https://www.iom.int/jahia/webdav/site/myjahiasite/shared/shared/mainsite/projects/showcase_pdf/Denmarkcases.pdf

Frederiksen HW, Norredam M. Sundhedsforhold hos nyankomne indvandrere—En rapport fra Forskningscenter for Migration, Etnicitet og Sundhed. Forskningscenter for Migration, Etnicitet og Sundhed (MESU), København, 2012;3–53. (In Danish).

Frederiksen HW, Krasnik A, Nørredam M. Policies and practices in the health-related reception of quota refugees in Denmark. Dan Med J. 2012;59:A4352.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Policy Statement on HIV Testing and Counselling in Health Facilities for Refugees, Internally Displaced Persons and other Persons of Concern to UNHCR. 2009;21. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/vct/unhcr.pdf?ua=1.

Fakoya I, Álvarez-del Arco D, Woode-Owusu M, Monge S, Rivero-Montesdeoca Y, Delpech V, et al. A systematic review of post-migration acquisition of HIV among migrants from countries with generalised HIV epidemics living in Europe: implications for effectively managing HIV prevention programmes and policy. BMC Public Health BMC Public Health. 2015;15:561.

Quota refugees [Internet]. Danish Immigr. Serv. [cited 2016 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.nyidanmark.dk/en-us/coming_to_dk/asylum/quota_refugees.htm.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards

The project was approved by the Danish Protection Agency (No 2012-41-0065). Further ethical approval regarding registry-based research is not required in Denmark. The data set was made available and analysed in an anonymous form by remote online access to the data set stored at Statistics Denmark.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Deen, L., Cowan, S., Wejse, C. et al. Refugees and family-reunified immigrants have a high incidence of HIV diagnosis and late presentation compared with Danish born: a nationwide register-based cohort study. Infection 46, 659–667 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-018-1167-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-018-1167-8