Abstract

Purpose of Review

Lung cancer care in the elderly is complex for both providers and patients, but a lung nurse navigator can help bridge the gap between providers and patients. The purpose of this paper is to review recent publications on the role of the lung nurse navigator and identify their importance in patient care with an emphasis on their impact on the elderly.

Recent Findings

Nurse navigation programs vary greatly from institution to institution but are increasingly used in a variety of diseases and roles. Multiple recent studies have shown that nurse navigators lead to a significant improvement in screening rates, time to initial treatment, compliance with treatment, and patient satisfaction, as well as improvement in quality of life among vulnerable populations.

Summary

Despite the growth within the navigation field, research still continues to be limited with respect to lung nurse navigators’ contributions to patient outcomes and overall emotional well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2019, more than 1.7 million new cancer cases are anticipated, with approximately 13% being newly diagnosed lung cancers [1]. Unfortunately, lung cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer mortality within the USA despite being one of the most preventable cancers. One primary reason for this is that only 16% of patients are diagnosed at a localized stage, showing the importance of early diagnosis and quality, timely care [1].

Recent research has shown that vulnerable populations are most at risk for both a late diagnosis and not receiving the timely comprehensive care they need. This led to recommendations to begin or improve programs that will increase access to care [2•]. Vulnerable populations are defined as a subset of disadvantaged individuals, traditionally identified as racial or ethnic minorities, socioeconomically disadvantaged, children, and/or the elderly (who receive substandard care compared to the standard Caucasian population) [2•].

Significantly, the elderly (defined as patients 65 years and older) make up the largest subset of newly diagnosed cancer cases each year [3]. Furthermore, adults over the age of 85 are the fastest-growing population group in the USA with cancer risk increasing with age and peaking in the patient’s 80s [1]. With the growing demands of the elderly, there is a need for increased focus on providing optimal care by helping these vulnerable adults navigate the healthcare system.

Barriers to Effective Care

Cancer care at baseline is a complex and multifactorial journey that is difficult for any patient to navigate, particularly for our more elderly patients. Barriers to standard oncology care can be physical or financial barriers such as geographic location, transportation, socioeconomic status, and insurance coverage, as well as psychosocial barriers such as patient education, perceptions of care, and social support [4,5,6]. Patient barriers are known to affect the process of care and treatment outcomes in cancer patients [5]. Vulnerable populations appear to be affected more by these barriers, as seen in a study conducted by Siegel and associates that estimated approximately one third of adult American cancer deaths could be averted with the elimination of socioeconomic disparities [7]. Examples of this include lower rates of cancer screenings among poverty-stricken patients, leading to a delay in diagnosis and treatment [3]. In 2011, cancer costs were estimated at $88.7 billion with rising out-of-pocket expenses contributing to patient financial toxicity [8•]. In addition to financial difficulties such as health insurance coverage, Hendren and associates found that the most common barriers for newly diagnosed cancer patients were difficulty with medical communication and lack of social support [5].

Cancer Care in the Elderly

Unfortunately, the effect of these barriers is compounded in the elderly for multiple reasons. These patients are often retired and living on a fixed income, leading to significant financial stress. Furthermore, these patients are often sicker at baseline with the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimating that 80% of older adults have at least one chronic condition with more than half having at least two [4]. These metabolic changes and comorbidities not only affect their ability to tolerate diagnostic tests and treatment but can also make it more difficult to attend appointments on a routine basis. Studies have also shown that the elderly face increased roadblocks in medical communication due to the reluctance to ask questions or share problems and goals of care with their healthcare provider [4, 8•]. Ideally, care is provided in a way that is consistent with the needs, values, and preferences of the patient, but without open communication lines, this can be difficult to achieve [8•].

Another barrier facing the elderly is that despite the large number of cancer patients among the elderly population, cancer research and trials have often excluded older adults [9]. Not until the creation of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology in 2000 did we start to see a drastic change in clinical trial inclusion criteria [10]. In 2015, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) additionally created a subcommittee to improve evidence-based guidelines through further research of older adults [11]. Traditionally, clinical trials have used chronological age to identify patients; however, many studies are showing that functional age may give providers a better perspective for treatment tolerance and overall prognosis [4, 9, 10, 12]. Functional status, nutritional status, cognition, mood, and social environment can all interfere with cancer treatment tolerance and thus must be taken into account when caring for the elderly with cancer [9]. In review of the literature, many of these barriers can be addressed by nursing interventions along the cancer continuum.

Nurse Navigation

While nursing can play several roles within the oncology care continuum, the role of nurse navigator may be the most pivotal to overall care. Since nurse navigation’s first conception in 1990 by Dr. Harold Freeman, the involvement of nurses within the multidisciplinary team has been shown to improve patient outcomes [13, 14]. Freeman was able to demonstrate that 5-year breast cancer survival rates improved through patient navigation by eliminating barriers and increasing access to screenings, and this process has since been replicated across several disease populations [14,15,16]. However, the role of the lung nurse navigator remains an evolving role in many institutions with little consistency or delineation of the role [17]. In response to this, there has been an increased effort from national societies to define nurse navigation and make it more consistent across the medical system (Table 1) [18, 19].

Logistically, nurse navigators coordinate the care provided by multiple providers to avoid duplication of testing, conflicting care plans, and hazardous polypharmacy and minimize patient confusion, all of which are particularly important when working with the elderly [17]. In other words, nurse navigators ensure care is patient-centered while directing patients through the complexities of the healthcare system by empowering patients through education and emotional support. Multiple studies have shown that these efforts result in improved understanding of the disease process, adherence to complex treatment regimens, and management of side effects, which ultimately lead to improved overall outcomes and satisfaction [5, 6, 20].

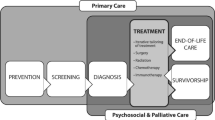

The tasks of nurse navigation are divided into four main categories: navigating the individual through communication, support, instruction, and coaching; facilitating care for the patient through interaction with others; maintaining resources; and documentation/record retrieval [21•]. From this, healthcare systems and nurse navigators break down these tasks into four foci across the spectrum of care, which includes screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship/end of life [21•]. While most of the data on the effect of a quality nurse navigator program is from other cancers, much of it can be extrapolated to lung cancer as well.

Screening

Lung nurse navigators often work with a myriad of specialists, which include general pulmonologists, interventional pulmonologists, radiologists, interventional radiologists, thoracic surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists. Through this network of specialties, lung nurse navigators work to improve identification of at-risk patients for lung cancer and navigate them through the continuum of care. In many programs, screening is a main focus of the lung nurse navigator [2•, 19]. Navigation programs as a whole have shown to increase screening rates; however, lung cancer screening still has significant room to improve [3, 15, 22]. In 2015, only 4% of the 6.8 million identified eligible Americans reported being screened for lung cancer through the use of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) [3]. Similar findings were noted in a study conducted by Nishi and associates, where they found less than 5% of Medicare enrollees who were eligible for LDCT screenings completed these screenings in 2016 [22]. It is proposed that this discrepancy is due to many contributing factors which include lack of awareness by both patients and providers, logistical challenges, cultural beliefs and perceptions regarding cancer, and lack of motivation [15, 22, 23•]. Lung navigators can bridge this gap through the development of community networks and providing education on the importance of timely lung screenings not only to patients but also to providers [21•]. In a meta-analysis conducted by Ali-Faisal and associates, they found that the presence of nurse navigators increased the likelihood of cancer screenings almost 2.5 times compared to the usual care [15]. Unfortunately, there is limited evidence that directly correlates lung nurse navigation with completion of screening and diagnostic CTs, but preliminary data is promising especially when extrapolating from studies across all cancer populations [21•].

Diagnosis

While patients often enter into navigation through screening, a large body of patients are also referred to navigators during the diagnostic phase of the continuum which consists of the initial diagnostic testing through the immediate pre-treatment phase [5, 21•]. Regardless of the timing of referral, the lung nurse navigator works to build a rapport with the patient that will promote comfort, empowerment, and clarity from the first interaction throughout the entire continuum of care. This relationship can have a major impact as patients who are undergoing diagnostic evaluation for cancer are notably anxious and often depressed, which can affect health-related quality of life [24]. Lung nurse navigators work to ease this angst by providing open and accessible communication and provide crucial education to ensure understanding of the diagnostic process and ultimately their diagnosis [8•, 25•]. Overall, this relationship leads to increased patient empowerment which allows a patient to move from passive recipient to an active participant within their multidisciplinary care team [24]. Not surprisingly, a systematic review conducted by Shusted and company showed that nurse navigators lead to improved patient follow-up after abnormal testing and to adherence to diagnostic recommendations, notably in vulnerable populations [2•].

In addition to this crucial supportive relationship, the nurse navigators also coordinate and streamline diagnostic testing for patients in an effort to minimize time to diagnosis and decrease biopsy complications [2•, 24]. One major aspect of this role is their coordination of multidisciplinary lung cancer tumor boards, which are designed to provide input that results in improved treatment plans for the patient [25•, 26, 27]. A retrospective study conducted over an 18-month period found that the implementation of an interprofessional lung cancer tumor board increased identification of early-stage non-small cell patients by 37% [26]. The nurse navigators are crucial to this impact by not only facilitating the tumor board and helping identify key patients to present but also by providing the follow-up for patients and explaining the tumor board recommendations in a manner that the patient can understand. Likely due to this close follow-up, studies show that nurse navigators decrease the time from diagnosis to treatment, which is a crucial time period in the care of cancer patients [16, 26]. Overall, patients guided by a lung nurse navigator progress from initial abnormal finding to appropriate treatment 19 days faster than those without the assistance of a nurse navigator [8•, 28].

This decrease in time to diagnosis is central to the novel “rapid” pathways that are being introduced around the world. For example, the UK National Health System (NHS) published a handbook in April 2018, detailing the goal of achieving 14-day and 28-day pathways from initial concern to lung cancer diagnosis by 2021 [29]. To achieve these goals, the patient must be seen by multiple providers and undergo many diagnostic studies in a short period of time which is particularly challenging for the elderly patient. As these rapid clinics become more common, the importance of an effective nurse navigator program will continue to increase.

Treatment

The role of the lung nurse navigator during treatment is often quite different from other disciplines involved in the care of the patient, particularly in the care of the elderly. A lung nurse navigator is uniquely suited to help assess tolerance of therapy, ensure a good functional status, and to maintain an ongoing conversation about goals of care. Studies have shown that maintaining independence and preventing functional decline and disability often are a health priority for older adults even without cancer [12]. One recommended method of doing so is utilizing the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) which evaluates physiological changes, functional status, comorbidities, cognition, psychological status, social environment, nutritional status, and polypharmacy [9, 30, 31]. However, studies evaluating the utility of this scoring system are mixed. Corre and associates state that the CGA can help to identify patients with natural poor prognosis based on independent variables such as functional and nutritional status, both of which nurse navigators can help promote. Despite this, in their multicenter, phase III randomized trial, CGA-based allocation of chemotherapy did not improve the survival outcomes of elderly patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer [31]. However, a retrospective chart review by Zibrik and associates reported that after the implementation of a lung nurse navigator program, the percentage of patients receiving systemic therapy increased from 57 to 69% [16].

Other studies have found improvement in quality of life during treatment with the aid of nurse navigators. In a pilot study conducted by Reinke et al., 40 newly diagnosed patients were randomized into either a standard of care protocol or a nurse-led telephone intervention where they communicated on a regular interval over a 3-month period to discuss symptom management and goals of care and address any psychosocial needs [32]. Results demonstrated that participants reported not only a higher degree of satisfaction during their treatment but also avoided additional office visits for symptom management [32]. This however is in contrast to a randomized study conducted by Flannery and colleagues, which did not find a statistically significant difference between usual care and a similar nurse-led phone intervention [33]. The likely difference in results may be due to the small sample size and decreased intensity of the intervention as only 5.5 of the 8 planned interventions occurred on average. Despite the results, investigators continue to believe that conducting systematic and frequent symptom assessments is essential in minimizing symptom burden and thereby helping maintain patients’ positive outlook [33]. This belief is validated by a systematic review conducted by Joo and colleagues that found the use of a nurse navigator or nurse-led case management improved patient’s quality of life while also reducing the number of hospital admissions among vulnerable populations [20]. Furthermore, nurse navigation or nurse case management was shown to improve self-efficacy, symptom control, and satisfaction with care [20].

Lastly, treatment is often aimed to cure or to prolong one’s life, but when advocating for our elderly patients, this focus may change from quantity to quality of life [8•, 12]. As a result, patient advocacy becomes the primary priority of a lung nurse navigator, with a particular focus on understanding the patient’s goals and values and validating that they are consistent with the plan of care.

Survivorship/End of Life

With advancements in lung cancer treatment and with continued improvements of screening programs, patients are living longer and therefore create a diversity of further health hurdles and experiences to be addressed by patients and navigators alike [17]. As a result, more patients require long-term follow-up in lung cancer survivor clinics. Although there is limited research on the role of nurse navigators in this setting, the relationship and rapport that they have developed with patients would certainly continue to be helpful; however, more research is being initiated [34]. In this phase, lung nurse navigators can educate patients on needed health maintenance and surveillance protocols to promote continued disease-free status and ensure patients are not lost to follow-up. Nurse navigators also provide an additional point of contact for primary care providers during this time to ensure provider understanding of previously provided treatment as well as recommended surveillance [35].

However, the nurse navigators also play a major role for those patients who are approaching the end of their life. Nurse navigation in this phase is focused not only on the physical symptoms but also the psychosocial and spiritual distress experienced by patients and their families [8•]. As noted, focus for the elderly lung cancer patient may not be the quantity of life, but instead the quality. It is imperative that the lung nurse navigator engages with the patient and their family to ensure understanding of goals in order to properly advocate on the patient’s behalf. This often can be a time of needed education for patients and their families to understand and prepare advanced directives and living wills accordingly. With the long-standing relationship that the nurse navigators have developed, they are uniquely suited to help the patients with this very personal decision.

Conclusion

Clearly, the lung nurse navigator plays a major and unique role in the care of the patient throughout the oncologic care continuum and is becoming even more important with elderly patients. At this time, the bulk of the literature shows great variety in the focus of each navigation program, but there is a consistent trend towards improved patient care. There have been several efforts to standardize navigation programs through guidelines and competencies; however, implementation has not been specified or mandated [19, 36, 37]. One major limitation of this review is the limited research specifically designed to study the impact of nurse navigators in the elderly, but it is reasonable to extrapolate the data obtained from the general oncologic population. Over the last several years, there has been increased emphasis in the field which we welcome, including the new January 2019 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for caring for the elderly [38].

Despite the lack of strong evidence to date, we have seen significant improvement in patient care and satisfaction within our clinic with the use of a strong nurse navigator program. Our ideal role of the nurse navigator can be seen in Fig. 1, which emphasizes the central nature of their position. They participate in all aspects of care, helping guide the patient and serving as the first line of contact for the patient throughout the cancer continuum. Their relationship with the patient is their most valuable tool and outstrips any benefit from specializing in a single foci of care such as lung cancer screening.

In conclusion, lung nurse navigators improve screening utilization, time to diagnosis and treatment, patient satisfaction, and many other major criteria in the care of the lung cancer patient by removing barriers to care. By building a rapport and meaningful connection with both the patient and their family, the nurse navigator can properly ensure alignment of patient’s goals and values with plans of care and optimize communication between all disciplines involved in the care. In order for lung nurse navigators to be truly effective, they must possess not only an understanding of cancer biology and lung physiology, symptom management, treatment variables, and side effects but also the ability to educate and advise patients, families, and providers; understand informed consent; and maintain confidentiality, all while being empathetic and culturally competent [2•]. Of course, more studies are needed to further optimize the role of the lung nurse navigator and to promote general education of the values for this type of program.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2019. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2019/cancer-facts-and-figures-2019. Accessed 5 Oct 2019.

• Shusted CS, Barta JA, Lake M, Brawer R, Ruane B, Giamboy TE, et al. The case for patient navigation in lung cancer screening in vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Popul Health Manag. 2019;22(4):347–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2018.0218This 2019 systematic review included 26 papers that evaluated the outcomes from nurse navigation programs in a variety of cancers. It is especially pertinent to this review as it focuses on the more vulnerable populations.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21551.

Marosi C, Koller M. Challenge of cancer in the elderly. ESMO Open. 2016;1:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2015-000020.

Hendren S, Chin N, Fisher S, Winters P, Griggs J, Mohile S, et al. Patients’ barriers to receipt of cancer care, and factors associated with needing more assistance from a patient navigator. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(8):701–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30409-0.

Phillips S, Villalobos AVK, Crawbuck GSN, Pratt-Chapman ML. In their own words: patient navigator roles in culturally sensitive cancer care. Support Cancer Care. 2019;27:1655–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4407-7.

Siegel RL, Jemel A, Wender RC, Gansler R, Ma J, Brawley OW. An assessment of progress in cancer control. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018:68329–39. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21460.

• Meneses L, Landier W, Dionne-Odom JN. Vulnerable population challenges in the transformation of cancer care. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2016;32(2):144–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2016.02.008This 2016 paper from Seminars in Oncology Nursing focuses on cancer care within vulnerable population, which includes elderly paper, the focus of this review. It gives an excellent breakdown of the disparities in health care and outcomes for these population and suggests next steps on how to overcome these obstacles.

Pamoukdjian F, Liuu E, Caillet P, Herbaud S, Gisselbrecht M, Poisson J, et al. How to optimize cancer treatment in older patients: an overview of available geriatric tools. Am J Clin Oncol. 2019;42(2):109–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000488.

Le Saux O, Falandry C, Gan HK, et al. Inclusion of elderly patients in oncology clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1799–804. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw259.

Hurria A, Levit LA, Dale W, Mohile SG, Muss HB, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Improving the evidence base for treating older adults with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology statement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3826–33. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0319.

Presley CJ, Reynolds CH, Langer CJ. Caring for the older population with advanced lung cancer. In: supportive care and decision making in thoracic surgery. ASCO Education Book. 2018;37:587–96. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_179850.

Freeman H, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117:3539–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26262.

Freeman HP. Patient navigation: a community centered approach to reducing cancer mortality. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21:11–4. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430154jce2101s_4.

Ali-Faisal SF, Benz Scott L, Colella TJF, Medina-Jaudes N. Patient navigation effectiveness on improving cancer screening rates: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Oncol Navig Surviv. 2017;8(7) http://www.jons-online.com/issues/2017/july-2017-vol-8-no-7/1648-patient-navigation-effectiveness. Accessed 30 Oct 2019.

Zibrik K, Laskin J, Ho C. Implementation of a lung cancer nurse navigator enhances patient care and delivery of systemic therapy at the British Columbia Cancer Agency. J Oncol Prac. 2016;12:e344–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2015.008813.

Colombani F, Sibe M, Kret M, Quintard B, Ravaud A, Saillour-Glenisson F. EPOCK study protocol: a mixed-methods research program evaluating cancer care coordination nursing occupations in France as a complex intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4307-7.

Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators. Helpful definitions. https://www.aonnonline.org/education/helpful-definitions. (2019) Accessed 30 Oct 2019.

Oncology Nursing Society. 2017 Oncology nurse navigator core competencies. https://wwwonsorg/oncology-nurse-navigator-competencies (2017) Accessed 2 Nov 2019.

Joo JY, Liu MF. Effectiveness of nurse-led case management in cancer care: systematic review. Clin Nurs Res. 2019;28(8):968–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773818773285.

• Gilbert J, Veazie S, Joines K, Winchell K, Relevo R, Paynter R, et al. Patient navigation models for lung cancer. AHRQ Rapid Evid Prod. 2018;18(19). https://doi.org/10.23970/AHRQEPCRAPIDLUNGThis publication from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in 2018 gives a comprehensive overview of the use of nurse navigators in all malignancies. Importantly, it also reviews multiple different toolkits that can be useful in creating and evaluating a nurse navigator program at the local hospitals.

Nishi S, Zhou J, Kuo YF, Goodwin J. Use of lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography in the Medicare population. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(1):70–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2018.12.003.

• Ali-Faisal SF, Colella TJ, Medina-Jaudes N, Benz Scott L. The effectiveness of patient navigation to improve healthcare utilization outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(3):436–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec2016.10.014This 2017 systematic review evaluates 25 articles focusing on the impact of nurse navigators on the rate of appropriate lung cancer screening and shows a significant increase in screening reats and complete care events. This review is important as it gives some of the most concrete evidence for the benefit of a nurse navigator program.

Jeyathevan G, Lemonde M, Brathwaite AC. The role of oncology nurse navigators in enhancing patient empowerment within the diagnostic phase for adult patients with lung cancer. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2017;27(2):164–70. https://doi.org/10.5737/23688076272164170.

• Munoz RD, Farshidpour L, Chaudhary UB, Fathi AH. Multidisciplinary cancer care model: a positive association between oncology nurse navigation and improved outcomes for patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(5):e141–5. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.CJON.E141-E145This 2018 retrospective study showed a statistically and clinically significant reduction in time from diagnosis to treatment in patients with GI cancer after implementation of a oncology nurse navigator. This reduction of nearly 27 days with the use of a nurse navigator has the potential to have significant effect of the overall treatment outcomes for these patients.

Peckham J, Mott-Coles S. Interprofessional lung cancer tumor board: the role of the oncology nurse navigator in improving adherence to national guidelines and streamlining patient care. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(6):656–62. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.CJON.656-662.

Ung KA, Campbell BA, Duplan D, Ball D, David S. Impact of the lung oncology multidisciplinary team meetings on the management of patients with cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2016;12(2):e298–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.12192.

Kunos CA, Olszewski S, Espinal E. Impact of nurse navigation on timeliness of diagnostic medical services in patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. J Community Support Oncol. 2015;13(6):219–24. https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0141.

Harrison C, Baldwin D, Sharkley, D. Implementing a Timed Lung Cancer Diagnostic Pathway: A Handbook for Local Health and Care Systems. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/implementing-timed-lung-cancer-diagnostic-pathway.pdf (2018). Accessed 6 Feb 2019.

Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, Topinkova E, Janssen-Heijinen MLG, Extermann M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(24):2595–603. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347.

Corre R, Greillier L, LeCaer H, Audigier-Valette C, Baize N, Berard H, et al. Use of a comprehensive geriatric assessment for the management of elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: the phase III randomized ESOGIA-GFPC-GECP 08-02 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1476–83. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5839.

Reinke L, Vig EK, Tartaglione EV, Backhus LM, Gunnink E, Au DH. Protocol and pilot testing: the feasibility and acceptability of a nurse-led telephone-based palliative care intervention for patients newly diagnosed with lung cancer. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;64:30–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2017.11.013.

Flannery M, Stein KF, Dougherty DW, Mohile S, Guido J, Wells N. Nurse-delivered symptom assessment for individuals with advanced lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2018;45(5):619–30. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.ONF.619-630.

Park G, Johnston GM, Urquhart R, Walsh G, McCallum M. Comparing enrollees with non-enrollees of cancer-patient navigation at end of life. Curr Oncol. 2018;25(3):e184–92. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.25.3902.

Powel LL, Seibert SM. Cancer survivorship, models, and care plans. Nurs Clin North Am. 2017;52(1):193–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2016.11.002.

Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Cahoun E, Dudley DJ, Fiscella K, Paskett E, et al. National Cancer Institute patient navigation research program: methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3391–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23960.

Johnston D, Sein E, Strusowki T. Standardized evidence-based oncology navigation metrics for all models: a powerful tool in assessing the value and impact of navigation programs. J Oncol Navig Surviv. 2017;8(5) http://www.jons-online.com/issues/2017/may-2017-vol-9-no-5/1623-value-impact-of-navigation-programs. Accessed 4 Nov 2019.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: older adults oncology. NCCN Guidelines 2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/senior.pdf. Accessed 16 Oct 2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense or US Government.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Pulmonology and Respiratory Care

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoder, C., Holtzclaw, A. & Sarkar, S. The Unique Role of Lung Cancer Nurse Navigators in Elderly Lung Cancer Patients. Curr Geri Rep 9, 40–46 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-020-00317-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-020-00317-7