Abstract

The aim of this study was to detect the prevalence of hepatitis E virus (HEV) in healthy blood donors so as to decipher the maintenance of (HEV) reservoir if any. Five hundred and eighty-one blood samples along with clinical information were collected from central blood bank, Kathmandu between February and March 2014. Samples were tested for hepatitis B virus surface antigen, anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies, anti-hepatitis A virus IgM, HEV antigen, HEV viral load and anti-HEV antibodies (IgM and IgG) by ELISA. Only those samples positive with anti-HEV IgM were tested for HEV RNA by reverse transcriptase nested PCR. Age adjusted prevalence of IgM anti HEV and IgG anti HEV were 3.6 and 8.3 % respectively. No significant difference in Median ALT levels was noted between HEV RNA positive and negative subjects. Sequence analysis of HEV shows all genotype belongs to genotype 1a. Phylogenetic analysis shows the virus has homology of 95 % with strain from India and Nepal outbreak of April 2014. This study sheds light on how inter epidemic reservoirs can be maintained in healthy population with asymptomatic cases. This raises an important question regarding nature of HEV as well as its tendency to circulate in blind sight and also cause periodic outbreaks in endemic setting like Kathmandu.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection is endemic in Kathmandu Valley the capital of Nepal. Four epidemics have been documented so far during 1973, 1981–1982, 1987 and 2005–2006 and variable numbers of sporadic acute hepatitis E occurred in between [4]. There have been decline in number of acute hepatitis E cases in recent years and hepatitis A infection has outnumbered HEV as an etiology of acute hepatitis in adults [3]. What maintains the virus in the population during low incidence period of acute hepatitis is a matter of debate. There are some evidences that rodents may serve as animal reservoirs for HEV [2].

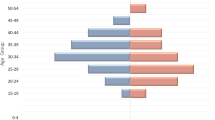

Occurrence of HEV viremia in healthy blood donors has been increasingly reported across the globe mainly from Europe [5], and China [1] where genotype 3 and 4 predominate. To explore the possibility of HEV viremia in healthy blood donors of Nepal, we collected blood samples along with demographic data from 581 healthy voluntary blood donors from central blood bank, Kathmandu, Nepal during February–March 2014. Study subjects constituted 401 men and 180 women volunteer blood donors. Median age of the subjects was 35 years (range 18–55). Elevated ALT levels (>40 IU/L) were noted in 81(13.9 %) with median ALT value of 23 IU/l (range 5–98 IU/L). IgG anti-HEV was detected in 56 samples (9.5 %) and IgM anti-HEV was detected in 27 samples 4.6 %). When adjusted for the age the prevalence of IgM anti HEV and IgG anti HEV were 3.6 and 8.3 % respectively. No significant difference in Median ALT levels was noted between HEV RNA positive and negative subjects. HEV RNA was purified from 50 μl of each serum sample and using a GenMagScript One-Step RT-PCR Kit for detection. The 25 μl reaction mixture contained 12.5 μl of 2× One-Step RT-PCR reaction buffer (Genmagbio, Beijing, China), 0.2 μl of GenMagScript RT Enzyme Mix, 5 μl of RNA, and primers (forward primer: BDHEVF (5′-GGTGGTTTCTGGGGTGAC-3′) and reverse primer: BDHEVR (5′-AGGGGTTGGTTGGATGAA-3′) and probe (BDHEVP; 5′-TGATTCTCAGCCCTTCGC-3′) at concentrations of 200 nM, respectively.HEV RNA was detected in 9 samples (1.54 %) by RT-PCR using the primers. Nested RT-PCR was carried out on serum samples to identify HEV sequences using two sets of degenerate oligonucleotide primers that corresponded to 700-nt segment of open-reading frame 1 ORF1. In one set of the nested RT-PCR, the primers BD31-1 (5′-YTRCTYTAYMTGCCYCARGA-3′, nt3898–3917) and BD31-2 (5′-TCCTCCATRATTATRCACTC-3′, nt4516–4535) were used in the first round PCR and primers BD32-1 (5′-ATWGTRCACTGYCGTATGGC-3′,nt3961–3980) and BD32-2 (5′-ATTTTGRGTRCTRTCAAACTC-3′, nt4477-4497) were used in the second round. In another set of the nested RT-PCR primers, BD33-1 (5′- CAGGGRATATCYGCRTGGAG-3′, nt4291–4310) and BD33-2 (5′- GCAAACCTRACRACATCAGG-3′, nt4888–4907) were used in the first round PCR and primers BD34-1 (5′- TGGTTCCGYGCYATTGARAA-3′, nt4339–4358) and BD34-2 (5′- GCYACAACMACACCAGCATA-3′, nt4849-4868) were used in the second round. Nested RT-PCR was carried out in 50 μl reactions mixtures with 7 μl RNA, 20 pmol of each primer, 5U AMV reverse transcriptase, and 5U Taq polymerase. The reverse transcription and amplification were performed in the same tube.

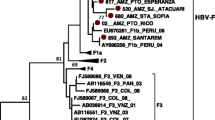

After purification, the PCR products were sequenced directly on both strands with the specific PCR primers synthesized by Invitrogen (Invitrogen, USA). Sequences were analyzed using MEGA5.2 software. Sequence alignments were made using MEGA 5.2 software package (version 5.2, http://www.megasoftware.net) to generate phylogenetic tree with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Genetic distances were calculated by using the Kimura two-parameter method. Sequence analysis of Hepatitis E virus shows all genotype belongs to genotype 1a. Phylogenetic analysis shows the virus has homology of 95 % with strain from India and Nepal outbreak of April 2014 (Fig. 1).

Asymptomatic HEV viremia in 1.54 % of the blood donors may pose significant risk of transfusion transmitted hepatitis E infection in highly endemic regions like Nepal. Further, HEV viremia in asymptomatic healthy blood donors reflects the ongoing subclinical HEV transmission. These HEV transmissions without any clinical and biochemical evidences of hepatitis, at any given time, may contribute to persistence of virus in the community even during period of low clinical acute hepatitis.

References

Guo QS, Yan Q, Xiong JH, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis E virus in Chinese blood donors. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:317–8.

He J, Innis BL, Shrestha MP, et al. Evidence that rodents are a reservoir of hepatitis E virus for humans in Nepal. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4493–8.

Raabe VN, Sautter C, Chesney M, et al. Hepatitis a screening for internationally adopted children from hepatitis A endemic countries. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53:31–7.

Shrestha SM. Hepatitis E in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2006;4:530–44.

Tedder RS, Tettmar KI, Brailsford SR, et al. Virology, serology, and demography of hepatitis E viremic blood donors in South East England. Transfusion. 2016;56(6 Pt 2):1529–36. doi:10.1111/trf.13498

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, B.P., Lama, T.K., Adhikari, A. et al. First report of hepatitis E virus viremia in healthy blood donors from Nepal. VirusDis. 27, 324–326 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13337-016-0331-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13337-016-0331-y