Abstract

Bevacizumab (Bev), a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor, when combined with standard first-line chemotherapy, shows impressive clinical benefit in advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (ns-NSCLC). Our study aims to investigate whether the addition of Bev to pemetrexed improves progression-free survival (PFS) in advanced ns-NSCLC patients after the failure of at least one prior chemotherapy regimens. Patients with locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic ns-NSCLC, after failure of platinum-based therapy, with a performance status 0 to 2, were eligible. Patients received 500 mg/m2 of pemetrexed intravenously (IV) day 1 with vitamin B12, folic acid, and dexamethasone and Bev 7.5 mg/kg IV day 1 of a 21-day cycle until unacceptable toxicity, disease progression or the patient requested therapy discontinuation. The primary end point was PFS. Between December 2011 and October 2013, 33 patients were enrolled, with median age of 55 years and 36.4 % men. Twenty-three patients (69.7 %) had received two or more prior regimens, and 28 patients (84.8 %) had received chemotherapy containing pemetrexed. The median number of the protocol regimens was 4. Median PFS was 4.37 months (95 % CI 2.64–6.09 months). Median overall survival (OS) was 15.83 months (95 % CI 10.52–21.15 months). Overall response rates were 6.45 %. Disease control rate was 54.84 %. No new safety signals were detected. No patient experienced drug-related deaths. The combination of Bev and pemetrexed every 21 days is effective in ns-NSCLC patients who failed of prior therapies with improved PFS. Toxicities are similar with historical data of these two agents and are tolerable. Our results may provide more a regimen containing Bev and pemetrexed for Chinese clinical practice in previously treated ns-NSCLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Both of the most common cancer and leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide are attributed to lung cancer [1]. Approximately 80 % lung cancer was diagnosed as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Once, most advanced NSCLC received platinum-containing two-drug therapy as first-line treatment with a median survival of 8∼10 months and 1-year survival rates of 30 to 40 % [2–5]. In recent years, several phase III trials have proved the remarkable efficacy of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine-kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) for EGFR-sensitive mutation subtypes [6–10], and a series of randomized phase III trials demonstrated a substantial clinical benefit of bevacizumab (Bev) plus carboplatin/paclitaxel or cisplatin/gemcitabine (GC), or cisplatin/pemetrexed for non-squamous NSCLC (ns-NSCLC) [11–13]; in addition, crizotinib was proven to be effective in lung tumors with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangements [14, 15]. The first-line regimens never have come to a standstill with a median survival surpassing 12 months at present.

However, patients who initially achieved disease control with first-line therapy will eventually experience disease progression and need second-line treatment. Several second-line regimens include monotherapy with docetaxel, pemetrexed, erlotinib, and gefitinib are approved in advanced NSCLC [16–21], but offer modest survival improvement, especially for patients who do not harbor activating mutations in EGFR. Therefore, we suggest that some targeted agents with low toxicity in combination with standard second-line therapy may provide longer survival benefit.

In advanced ns-NSCLC, pemetrexed was proven superior to gemcitabine when combined with platinum as first-line treatment [2]. Two phase III trials independently brought pemetrexed to a maintenance therapy after platinum-based chemotherapy induction [22, 23]. For recurrent NSCLC progressed after one previous chemotherapy regimen, pemetrexed resulted in clinically equivalent efficacy outcomes, but with significantly fewer side effects compared with docetaxel in a phase III trial [20], followed that pemetrexed has since been shown to be more efficacious in non-squamous patients [24].

In the early phase I trials, when Bev alone or with cytotoxic chemotherapy agents, pharmacokinetics studies were researched and toxicities were generally well tolerated [25, 26]. Bev combined with pemetrexed was evaluated for the first time in the 2009 phase II study [27], but pharmacokinetics was referred to the early phase I trials, as well as subsequent studies of Bev in combination with chemotherapy [25, 26]. Several phase III studies of Bev incorporated into platinum-based chemotherapy demonstrated a substantial clinical benefit for previously untreated ns-NSCLC [11–13]. Since then, Bev showed efficacy in maintenance setting, and the phase III AVAPERL trial [13] demonstrated that Bev plus pemetrexed maintenance was associated with a significant PFS benefit compared with Bev alone and acceptable safety.

Based on the efficacy of pemetrexed as second-line therapy and the tolerability of the combination of Bev plus pemetrexed, this trial was conducted to assess the efficacy and safety of the addition of Bev to pemetrexed in patients with advanced ns-NSCLC progressing after one or more chemotherapy regimens.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients aged 18 years or older with histologically or cytologically confirmed, locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic ns-NSCLC and failed of prior therapy were eligible. Eligibility criteria also included ECOG performance status (PS) of 0 to 2, measurable or valuable lesion as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function. Exclusion criteria included predominantly squamous-cell cancer, history of grade 2 hemoptysis (12 tsp or more per event), and uncontrolled hypertension (blood pressure ≥150/100 mmHg), symptomatic central nervous system (CNS) metastases, or unable to interrupt aspirin, anticoagulants, or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The protocol was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Guideline for Good Clinical Practice.

Procedures

This study was a single-arm phase II trial in Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, China. Patients received 500 mg/m2 of pemetrexed intravenously (IV, over 10 min [20]) day 1 and Bev 7.5 mg/kg (IV, which dose was previously used in AVAPERL [13]) day 1 of a 21-day cycle until unacceptable toxicity, disease progression or the patient requested therapy discontinuation. Pemetrexed was recommended at an optimal dose of 500 mg/m2 every 3 weeks in monotherapy or combined therapy [13, 20, 28], while Bev was at a dose of 7.5 mg/kg every 3 weeks ever since the AVAIL study confirmed that Bev (7.5 or 15 mg/kg) similarly improved PFS when combined with GC [11, 13]. In addition, when pemetrexed was combined with Bev, the regimen was delivered as above [13]. Bev was initially administered over 90 min; if well tolerated, second infusion was delivered over 60 min and subsequently 30 min. Patients were premedicated with dexamethasone (3.75 mg orally twice per day, the day before, the day of, and the day after pemetrexed of each cycle), vitamin B12 (1000 μg intramuscularly before the first dose of pemetrexed and was repeated approximately every 9 weeks), and folic acid (350–1000 μg orally daily).

Dose modifications

For hematological toxic effects, a pemetrexed dose was withheld until the absolute neutrophil count was 1.5 × 109/L or greater and platelet count was 100 × 109/L or greater before the start of next cycle, and treatment was resumed at 75 % of the previous pemetrexed dose. For clinically significant grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicities, a pemetrexed dose reduction of 25 % was permitted at the investigator’s discretion. Bev dose modifications were not allowed. Patients who had to discontinue combination therapy were allowed to continue Bev monotherapy because of pemetrexed-related adverse events or were permitted to continue pemetrexed monotherapy because of unacceptable Bev-related adverse events.

Assessments

Radiographic tumor assessments were performed at baseline and every 6 weeks. Responses were assessed using RECIST 1.1 [29]. Physical examination and laboratory evaluations were repeated before each therapy cycle. Safety was assessed at each cycle and every month follow-up with the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) Version 3.0. Efficacy analysis was performed in the patients who received at least two dose of treatment. The safety population consisted of patients who entered and received at least one dose of therapy.

Statistical analysis

The primary end point was PFS, defined as the time from registration to the time of documented disease progression or death from any cause. Secondary end points included overall survival (OS) which was defined as the time from the date of registration to date of death due to any cause; disease control rate (DCR) which was defined as the best tumor response of complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or stable disease (SD) from the first dose; duration of clinical benefit (CR/PR/SD) which was defined as the interval from the first documented CR/PR/SD until progression disease (PD) or death resulting from any cause; objective response rates (RR) which was defined as the best tumor response of complete response CR/PR from the first dose; duration of tumor response which was defined as the interval from the first documented CR/PR until PD or death resulting from any cause; and toxicities. Time to event end points was analyzed with Kaplan-Meier method with 95 % confidence interval (CI) using SPSS version 19.0. The Cox regression model was used to test whether response to the previous pemetrexed can predict for a difference in PFS after adjusting for all baseline factors.

Results

Patients

From December 2011 to October 2013, 33 patients were enrolled to receive at least one cycle of pemetrexed plus Bev regimen and comprised the safety population. Data were frozen as of April 13, 2014. All patients were of active treatment at the time of this analysis. Thirty-one patients were evaluable for response. Two patients was assigned but treated only one cycle because of poor PS or the patient’s refusal. Demographics and baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age was 55 years (range 36 to 75 years), with 84.8 % of patients having PS of 0 or 1 at baseline, 36.4 % of patients being male, 75.8 % nonsmokers, and all patients having stage IV disease. Twenty-three patients (69.7 %) had received two or more prior regimens and Twenty-eight patients (84.8 %) had received chemotherapy containing pemetrexed.

Treatment

The median number of cycles of chemotherapy administered was 4 (range 1–13). The mean dose intensity of Bev was 99.7 %. The mean dose intensity of pemetrexed was 104.9 %. There is currently one patient still on pemetrexed treatment. Two patients omitted any one of protocol drugs: one continued Bev monotherapy after 7 cycles because of hematologic toxicity; another one continued pemetrexed monotherapy after 5 cycles because of hypertension toxicity. Only one patient required discontinuation of combination therapy after 12 cycles, who experienced dose reduction previously, because of nephrotoxicity and hematologic toxicity. Other reasons for stopping treatment were disease progression (18 patients), patient choice (13 patients). Eighteen patients (54.5 %) received follow-up systemic treatments, and six patients (18.2 %) received two systemic therapy regimens (Table 2 shows the exposure of study drug, and Table 3 shows the follow-up anticancer treatments).

Efficacy

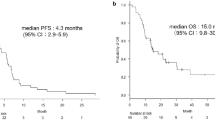

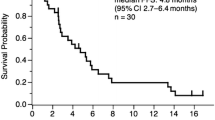

With a median follow-up of 12.23 months (range 4.00–21.73), 30 patients (90.91 %) reached PFS end points, among which 29 experienced disease progression and one death. Median PFS was 4.37 months (95 % CI 2.64–6.09) with 6-month PFS rate of 36.36 % (Fig. 1). There were no differences in PFS when stratified by gender (female, male), PS (0/1, 2), smoking status (current or ex-smoker, never smoker), EGFR mutation status (mutant type, wild type), and number of prior regimens (1, 2, or more) (Table 4). Response to previous pemetrexed (CR/PR, SD, PD/unknown, p = 0.251) did not predict for a difference in PFS after adjusting for gender, PS, smoking status, EGFR mutation status, and number of prior regimens. Twenty patients received subsequent anticancer treatments. Twenty patients (60.61 %) died, and median overall survival was 15.83 months (95 % CI 10.52–21.15) with a 1-year survival rate of 45.45 % (Fig. 2).

Thirty-one patients were assessable for treatment response. No patient achieved a complete response, and two patients achieved a partial response for ≥6 weeks, the objective response rate was 6.45 %. The two patients separately made response duration of 3.83 and 5.27 months. Another two patients achieved a partial response after 4 cycles but have not been confirmed. Disease control rate (CR + PR + SD) was 54.84 % with a median duration of clinical benefit of 6.03 months (95 % CI 2.16–9.91). Another nine patients achieved a stable disease after 2 cycles but have not been confirmed.

Safety

Toxicity was minimal and tolerable (Table 5). Three patients (9.09 %) had grade 3 neutropenia; one patient (3.03 %) had grade 3 thrombocytopenia and one patient (3.03 %) had grade 4 thrombocytopenia; one patient (3.03 %) had grade 3 anemia; three patients (9.09 %) had grade 3 fatigue; two patients (6.06 %) had grade 3 anorexia; one patient (3.03 %) had grade 3 nausea; one patient (3.03 %) had grade 3 vomiting; two patients (6.06 %) had grade 3 infection; and three patients (9.09 %) had grade 3 hypertension. Throughout the study, although ten patients experienced grade 3 or 4 toxicity, no hemorrhagic events of grade 3 or greater were seen at any point and no patient experienced drug-related deaths.

Discussion

We found that the addition of Bev to pemetrexed monotherapy was associated with favorable PFS and acceptable toxicity in previously treated patients with advanced NSCLC.

Current FDA-approved agents for advanced NSCLC salvage therapy include docetaxel, pemetrexed, and erlotinib in unselected patients with response rates less than 10 % and 1-year survival rates approximately 30 % [17, 18, 20]. This study of pemetrexed plus bevacizumab demonstrates a favorable PFS of 4.37 months (95 % CI 2.64–6.09) and 1-year survival rate of 45.45 % compared with historical controls. The median PFS of pemetrexed reported in the second-line setting JMEI study [20] was 2.9 months with 1-year survival rate of 29.7 % [20]. The overall response rate (ORR) (6.45 %) in the evaluable population in this study seems lower than that in JMEI study (overall RR 9.1 %) [20], which may be due to that the patient characteristics of these two trials have distinctions. In this study, patients who hold EGFR-sensitive mutations (eight patients) have been treated with EGFR-TKIs previously (although 18 among 25 patients of EGFR wild type or unknown also previously took oral EGFR-TKIs). Moreover, five patients (15.15 %) had received >1 prior cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens for metastatic disease and 23 (69.70 %) patients experienced disease progression after chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs. In brief, this study enrolled a heavily pretreated population (69.7 % with ≥2 prior regimens). The JMEI study limited patients to one prior chemotherapy regimen and did not received oral EGFR-TKIs before. As we know, benefit from salvage chemotherapy after the failure of chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs is smaller than that after the failure of EGFR-TKIs or chemotherapy alone [20, 30, 31]. Furthermore, because Bev is not under medical insurance coverage in China, patients entered in this study mostly have a good economic condition and will receive active treatment, while the other (13 patients) cannot bear the cost during the treatment and choose to drop out, leading a low overall RR. However, patients had a longer 1-year survival rate. One possible reason was that patients and physicians in China always made more lines of therapies. Moreover, patients entering into this study often had a strong interest in their both going-on and going-off treatment. Eighteen patients (54.5 %) received follow-up systemic treatments, and six patients (18.2 %) received two systemic therapy regimens, leading to a longer 1-year survival rate.

In addition, 28 patients (84.8 %) in this study had previously received chemotherapy containing pemetrexed, while patients with prior pemetrexed treatment were ineligible in the JMEI study, either in other pemetrexed-combined regimens. Previous randomized phase III studies of pemetrexed in second-line therapy, maintenance therapy, and first-line therapy revealed its activity and tolerability [2, 20, 22, 23], especially for ns-NSCLC [24]. Quality of life is so emphasized that reintroduction of pemetrexed is a preferred choice. Pemetrexed-refractory NSCLC patients still benefited from Bev in combination with pemetrexed. This challenge is inspired by the experience of patients with EGFR-positive, irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) that better response was seen with the combination of irinotecan and cetuximab compared to cetuximab alone [32]. Antiangiogenic therapy (Bev), which prevents the development of new blood vessels to inhibit tumor growth, decreases interstitial pressure to improve drug delivery to the tumor, and enables the regression or normalization of tumor vessels, can reverse cytotoxic drug-resistance, like cetuximab.

Although driver mutations have been identified in a part of patients of lung cancer, target therapies are either unavailable or have yet to be identified for other patients. Therefore, chemotherapy, whether first-line or second-line, still weighs! Platinum-based, two-drug chemotherapy is considered a standard of care worldwide for patients with advanced NSCLC [3, 33]. Among many second-line phase III studies [17, 18, 34–37], only the BR.21 trial [18] investigating erlotinib versus placebo and the TAX 317 trial [17] investigating docetaxel versus best supportive care showed a significant improvement in overall survival (OS). The 2009 meta-analysis compared doublet chemotherapy with single-agent chemotherapy as second-line treatment for advanced NSCLC and concluded that doublet chemotherapy does not improve OS compared to single agent [38]. These studies manifested that cytotoxic treatments reached an apparent efficacy plateau and additional treatment options were needed.

At the same time, many phase III trials of targeted agents in combination with standard second-line treatment have failed to show significant improvement in OS. The ZODIAC study [39] investigated the efficacy of adding vandetanib to docetaxel as second-line treatment of NSCLC but failed to show a significant improvement in OS. The BeTa study [40] assessed efficacy and safety of erlotinib plus Bev in recurrent or refractory NSCLC, but did not demonstrate addition of Bev to erlotinib improving survival. Likewise, the addition of cetuximab to pemetrexed or docetaxel failed to improve clinical benefit in patients previously treated with platinum-based therapy as interpreted in the SELECT study [41].

Treatment with the combination of pemetrexed and Bev was well tolerated. The most common grade 3 toxicity was fatigue (9.09 %), neutropenia (9.09 %), and hypertension (9.09 %), which were easily manageable with dose reduction, discontinuation, or medications decided by the physician. There was no fatal hemorrhage, as the protocol excluded squamous cell histology and adopted a 7.5 mg/kg dose level of Bev. There was one patient who suffered from grade 4 thrombocytopenia, who was on the third-line therapy and after 12 cycles of pemetrexed plus bevacizumab.

The regimen containing Bev and pemetrexed maintenance was associated with a significant PFS benefit compared with Bev alone after platinum-based chemotherapy plus Bev induction [13]. However, few trails have reported the addition of Bev into second-line therapy or beyond except for the phase II trial of pemetrexed plus Bev for second-line therapy of patients with advanced NSCLC [42]. The study did not meet its primary end point of at least 70 % 3-month PFS. It adopted a larger dose of Bev (15 mg/kg) than the dose (7.5 mg/kg) in this study. Expectedly, it had more grade 3 or 4 toxicities (37.5 % grade 3 or 4 hematologic AE, 75 % grade 3 or 4 nonhematologic) than toxicities in this study (18.2 % grade 3 0r 4 hematologic AE, 36.4 % grade 3 or 4 nonhematologic). In another randomized phase II trial, patients were treated with the combination of pemetrexed, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab after failed of at least one prior regimen. As might be expected, the response rate was 27 %, and grade 3 hypertension occurred in 17 % patients, where two-drug chemotherapy was combined with a dose of Bev of 15 mg/kg. In other words, efficacy of the combination of bevacizumab and chemotherapy in previously treated advanced ns-NSCLC patients needs further studies to confirm.

There were no differences in PFS when stratified by gender, PS, smoking status, EGFR mutation status, and number of prior regimens. The results may suggest that patients never smoked, having a better PS or less prior regimens could gain most benefit from bevacizumab plus pemetrexed. The results had no statistical significance may be due to the small sample size. Response to previous pemetrexed did not predict for a difference in PFS after adjusting for these subgroups. It implied that previous response to pemetrexed did not influence the choice of pemetrexed plus Bev as a salvage therapy for advanced ns-NSCLC.

We demonstrated such a trial of pemetrexed plus Bev administering to previously treated advanced ns-NSCLC patients. Differently, patients enrolled in this study were heavily treated with cytotoxic and targeted therapies; patients who had previously received pemetrexed were not an exclusion criterion, and it was delivered at a dose of Bev at 7.5 mg/kg. This represented an improvement in the median PFS compared with the PFS of 2.9 months reported for a number of single cytotoxic agents administered as second-line therapy for advanced NSCLC. Nonetheless, limitations of this study are its small sample size and a part of patients choose to drop out during the treatment. In view of its promising efficacy and modest toxicity, further phase III study is needed to verify the regimen of pemetrexed plus Bev as a salvage therapy of advanced ns-NSCLC.

References

Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(1):10–30.

Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3543–51. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375.

Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):92–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011954.

Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn Jr PA, Presant CA, Grevstad PK, Moinpour CM, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;19(13):3210–8.

Sandler AB, Nemunaitis J, Denham C, von Pawel J, Cormier Y, Gatzemeier U, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;18(1):122–30.

Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947–57. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810699.

Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2380–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0909530.

Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S, Okamoto I, Tsurutani J, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):121–8. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X.

Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):239–46. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70393-x.

Zhou C, Wu Y-L, Chen G, Feng J, Liu X-Q, Wang C, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):735–42. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70184-x.

Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, Ramlau R, Gorbounova V, Hirsh V, et al. Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1227–34. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5466.

Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2542–50. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061884.

Barlesi F, Scherpereel A, Rittmeyer A, Pazzola A, Ferrer Tur N, Kim JH, et al. Randomized phase III trial of maintenance bevacizumab with or without pemetrexed after first-line induction with bevacizumab, cisplatin, and pemetrexed in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAPERL (MO22089). J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;31(24):3004–11. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3749.

Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(18):1693–703. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1006448.

Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crino L, Ahn MJ, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385–94. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214886.

Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, Socinski MA, Gervais R, Wu YL, et al. Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): a randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9652):1809–18. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4.

Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, Mattson K, Gralla R, O’Rourke M, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;18(10):2095–103.

Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123–32. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050753.

Sun JM, Lee KH, Kim SW, Lee DH, Min YJ, Yun HJ, et al. Gefitinib versus pemetrexed as second-line treatment in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy (KCSG-LU08-01): an open-label, phase 3 trial. Cancer. 2012;118(24):6234–42. doi:10.1002/cncr.27630.

Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, Pereira JR, De Marinis F, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2004;22(9):1589–97. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163.

Garassino MC, Martelli O, Broggini M, Farina G, Veronese S, Rulli E, et al. Erlotinib versus docetaxel as second-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and wild-type EGFR tumours (TAILOR): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(10):981–8. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70310-3.

Paz-Ares L, de Marinis F, Dediu M, Thomas M, Pujol JL, Bidoli P, et al. Maintenance therapy with pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care after induction therapy with pemetrexed plus cisplatin for advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (PARAMOUNT): a double-blind, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):247–55. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70063-3.

Ciuleanu T, Brodowicz T, Zielinski C, Kim JH, Krzakowski M, Laack E, et al. Maintenance pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care for non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2009;374(9699):1432–40. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61497-5.

Scagliotti G, Brodowicz T, Shepherd FA, Zielinski C, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, et al. Treatment-by-histology interaction analyses in three phase III trials show superiority of pemetrexed in nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol: Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer. 2011;6(1):64–70. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f7c6d4.

Margolin K, Gordon MS, Holmgren E, Gaudreault J, Novotny W, Fyfe G, et al. Phase Ib trial of intravenous recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor in combination with chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer: pharmacologic and long-term safety data. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;19(3):851–6.

Gordon MS, Margolin K, Talpaz M, Sledge Jr GW, Holmgren E, Benjamin R, et al. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of recombinant human anti-vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;19(3):843–50.

Patel JD, Hensing TA, Rademaker A, Hart EM, Blum MG, Milton DT, et al. Phase II study of pemetrexed and carboplatin plus bevacizumab with maintenance pemetrexed and bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27(20):3284–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8181.

Smit EF, Mattson K, von Pawel J, Manegold C, Clarke S, Postmus PE. ALIMTA (pemetrexed disodium) as second-line treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase II study. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol / ESMO. 2003;14(3):455–60.

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2000;92(3):205–16.

Fan Y, Huang ZY, Yu HF, Luo LH. Efficacy of salvage chemotherapy in the advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients who failed the treatment of chemotherapy and EGFR-TKI]. Zhonghua Zhong liu za zhi [Chinese Journal of Oncology]. 2010;32(11):859–63.

Dong L, Han ZF, Feng ZH, Jia ZY. Comparison of pemetrexed and docetaxel as salvage chemotherapy for the treatment for nonsmall-cell lung cancer after the failure of epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Int Med Res. 2014;42(1):191–7. doi:10.1177/0300060513505808.

Loupakis F, Pollina L, Stasi I, Ruzzo A, Scartozzi M, Santini D, et al. PTEN expression and KRAS mutations on primary tumors and metastases in the prediction of benefit from cetuximab plus irinotecan for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27(16):2622–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2796.

Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. Bmj. 1995;311(7010):899–909.

Wachters FM, Groen HJ, Biesma B, Schramel FM, Postmus PE, Stigt JA, et al. A randomised phase II trial of docetaxel vs docetaxel and irinotecan in patients with stage IIIb-IV non-small-cell lung cancer who failed first-line treatment. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(1):15–20. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602268.

Fossella FV, DeVore R, Kerr RN, Crawford J, Natale RR, Dunphy F, et al. Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel versus vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens. The TAX 320 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;18(12):2354–62.

Georgoulias V, Kouroussis C, Agelidou A, Boukovinas I, Palamidas P, Stavrinidis E, et al. Irinotecan plus gemcitabine vs irinotecan for the second-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer pretreated with docetaxel and cisplatin: a multicentre, randomised, phase II study. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(3):482–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602010.

Takeda K, Negoro S, Tamura T, Nishiwaki Y, Kudoh S, Yokota S, et al. Phase III trial of docetaxel plus gemcitabine versus docetaxel in second-line treatment for non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a Japan Clinical Oncology Group trial (JCOG0104). Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol/ ESMO. 2009;20(5):835–41. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdn705.

Di Maio M, Chiodini P, Georgoulias V, Hatzidaki D, Takeda K, Wachters FM, et al. Meta-analysis of single-agent chemotherapy compared with combination chemotherapy as second-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27(11):1836–43. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5844.

Herbst RS, Sun Y, Eberhardt WE, Germonpre P, Saijo N, Zhou C, et al. Vandetanib plus docetaxel versus docetaxel as second-line treatment for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (ZODIAC): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(7):619–26. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70132-7.

Herbst RS, Ansari R, Bustin F, Flynn P, Hart L, Otterson GA, et al. Efficacy of bevacizumab plus erlotinib versus erlotinib alone in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of standard first-line chemotherapy (BeTa): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9780):1846–54. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60545-X.

Kim ES, Neubauer M, Cohn A, Schwartzberg L, Garbo L, Caton J, et al. Docetaxel or pemetrexed with or without cetuximab in recurrent or progressive non-small-cell lung cancer after platinum-based therapy: a phase 3, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(13):1326–36. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70473-x.

Adjei AA, Mandrekar SJ, Dy GK, Molina JR, Adjei AA, Gandara DR, et al. Phase II trial of pemetrexed plus bevacizumab for second-line therapy of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: NCCTG and SWOG study N0426. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):614–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6406.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients who entered this study. We acknowledge the contributions of staffs of the department of Medical Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Center for their assistance in either the conduct of this study or the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, L., Liu, K., Jiang, Z. et al. The efficacy and safety of pemetrexed plus bevacizumab in previously treated patients with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (ns-NSCLC). Tumor Biol. 36, 2491–2499 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-014-2862-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-014-2862-4