Abstract

Background

Osteosarcomas of head and neck region have unique biology and exhibit a clinical behavior and natural history that is distinct from osteosarcomas of the trunk and extremities. Our understanding of this malignant bone tumor is largely based on data from single institutions or compiled from registries, and hence the clinical practice guidelines seem confusing and conflicting.

Aims and Objectives

To analyze the demographic profile, disease characteristics and survival outcomes of osteosarcoma of head and neck region.

Materials and Methods

Retrospective analysis of the patients treated for osteosarcoma of head and neck region with curative intent in the period between the years 2001–2013 at a tertiary cancer center from South India.

Results

A total of 14 patients were treated in the said period with a mean age of 37 years. The most common site was mandible (n = 9 patients) followed by maxilla (n = 4) and paranasal sinuses (n = 1). Conventional osteoblastic variant of OS was the most common histological variant (n = 8) followed by the chondroblastic variant (n = 5). The median disease-free survival was 41.7 months, whereas the median overall survival of our patient cohort was 47.6 months. A formal analysis of various prognostic factors showed only postoperative margin positivity to be the single important factor affecting the survival outcomes.

Conclusion

Head and neck osteosarcoma that most commonly afflicts the jaw bones occurs in the fourth decade of life. Despite being a small series, our study does highlight the importance of achieving a margin-negative resection as a part of the multimodality treatment of head and neck osteosarcomas. Considering the relative paucity of data, there is a need for multi-institutional collaborative studies to refine the therapeutic strategies for the management of patients with head and neck osteosarcomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteosarcomas are rare malignant bone tumors which most commonly arise from the metaphysis of long bones of the extremity [1]. The head and neck region is a rare sub-site of osteosarcoma, with less than 10% of all cases of osteosarcoma and <1% of all the head and neck malignancies [2]. In comparison with the extremity osteosarcoma, osteosarcoma of the head and neck region tends to occur in the third or fourth decades of life, has a lesser propensity to metastasize to pulmonary and extra-pulmonary sites, is not easily amenable for R0 resections considering the anatomical constraints and has a higher associated lethality [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. In the current study, we have reviewed our experience treating patients with osteosarcoma of head and neck region with a curative intent.

Materials and Methods

The historical records of patients treated for head and neck osteosarcomas from 2001 to 2013 were reviewed, and all the relevant clinical details including demographic profile, histological variants, treatment and disease outcomes were captured and analyzed. Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS 17.0 statistical software.

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

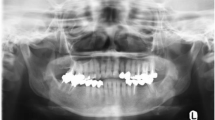

Seventeen patients presented to our institute in the said period, 14 of whom were treated with curative intent and were included in the analysis. The mean age of our patients in this study cohort was 37 years (range 14–76), which included eight women and six men (male/female ratio = 1:1.14). None of the patients reported any family history of any malignancy, pre-existing Paget’s disease of bone, fibrous dysplasia or any prior radiation exposure. The most common site of origin in the head and neck region was found to be mandible (n = 9) followed by maxilla (n = 4) and the paranasal sinus (n = 1). Conventional osteoblastic variant (m = 8) was the most common histological variant, followed by chondroblastic variant; (n = 5) one patient had a low-grade osteosarcoma (Table 1).

Management Details

All patients were offered multimodality treatment comprising surgical resection with adjuvant radiation with or without chemotherapy as per the decision of the multi-disciplinary tumor board. A R0 resection was deemed not upfront possible in three patients, and these patients were offered neo-adjuvant chemotherapy after a multi-disciplinary board discussion. The definitive surgical procedures performed included composite resection in nine patients, maxillectomy in two patients and craniofacial resection in three patients. Reconstructive procedures which included regional flaps/free flaps and definitive obturators were done as deemed appropriate to the defect following resection. Microscopic margin positivity was noted in three patients (21.3%), while soft tissue extension of the tumor was seen in 12 patients (85.7%).

Thirteen patients with any one the adverse risk factors, i.e., large-sized tumor (>7 cm), high-grade tumors, soft tissue extension or margin positive resections, were offered postoperative adjuvant treatment. Seven patients actually received postoperative radiation, 3 patients received both postoperative chemotherapy and radiation, while two patients refused any form of adjuvant treatment. One of the patients who received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy could not be offered further adjuvant treatment. The patient of a low-grade osteosarcoma was managed by definitive surgery only. The chemotherapeutic agents included ifosfamide, doxorubicin and cisplatin. External beam radiation therapy was delivered using conventional fractionation to a planned dose of 60 Gy.

Survival Outcomes

All the patients were under regular follow-up at two-monthly intervals for the first two years, three monthly in the third year, six monthly in the fourth and fifth year and yearly after 5 years. The median duration of follow-up period was 50 months (mean 53 months, range 17–159 months). At the time of last follow-up, 6 patients were free of disease. Two patients had local recurrence and could not be salvaged. Six patients had distant metastasis, all in the lung and among them one patient could be salvaged by lung metastasectomy and is currently disease-free. The other patients with distant metastasis were managed either with palliative chemotherapy or on best supportive care.

The median overall survival of our patient cohort was 47.6 months; the disease-free survival was 41.7 months. Analysis of the various prognostic factors such as age (<20, >20 years), gender, site (maxilla, mandible), histological variant (osteoblastic, chondroblastic), tumor size (<7, >7 cm), presence of soft tissue extension, surgical margin positivity, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, postoperative adjuvant treatment was done as in Table 1. Among all the factors studied, only surgical margin status seemed to have a bearing on the survival outcomes. Our series suggested a trend for better survival with the use of adjuvant external beam radiation therapy, with or without chemotherapy; however, this trend was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Osteosarcomas of the head and neck region are rare [10], have a unique biology and exhibit a clinical behavior and natural history distinct from their counterparts of the trunk and extremities. The exact etiology of osteosarcomas is still largely unknown; however, some predisposing factors are implicated its development including prior exposure to radiation, pre-existing Paget’s disease of bone, fibrous dysplasia, multiple osteochondromatosis and chronic osteomyelitis. Isolated cases of trauma and myositis ossificans have also been stated as potential contributing factors [11].

The main signs and symptoms of head and neck osteosarcomas include local swelling, pain, paresthesia and ulceration [12]. The median age of patients in our study cohort was 37 years which was comparable to other studies. It is believed that that the mean age at diagnosis of head and neck osteosarcomas is at least 10–15 years higher than for osteosarcomas in other parts of the body. Most of the studies of head and neck osteosarcomas report a male preponderance, and our series found the incidence to be marginally higher among females [13]. The jaw bones, i.e., mandible and maxilla, were the most common sites in the vast majority of the reported series. Our series showed a higher incidence of osteosarcomas in the mandibular region, whereas a few other reported studies have shown mixed observations (Table 2).

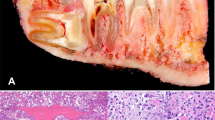

Osteosarcoma is an osteoid-producing tumor and the identification of anaplastic stromal cells producing osteoid aids in the histological diagnosis. Osteosarcomas can be further classified based on their cellular differentiation as osteoblastic, chondroblastic and fibroblastic variants. Chondroblastic variant was observed in 35.1% of the patients of our series, while the literature review again showed mixed observations. According to a few other reports, nearly half of the jaw osteosarcomas were chondroblastic [3, 10, 12, 14], which is considered to be an adverse prognostic factor [15, 16]. Some series also showed a higher incidence of fibroblastic variant of osteosarcoma, which incidentally seems to have the best prognosis, and interestingly no cases of the fibroblastic variant were observed in our series.

The current philosophy of management of treatment for extremity osteosarcomas is neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. In contrast, the management philosophy of head and neck osteosarcomas is primarily a multi-disciplinary approach. The major component of the multi-disciplinary management for head and neck osteosarcomas is an adequate surgical resection with wide margins. However, due to the anatomic characteristics of the head and neck region, the surgical resection may be difficult [6,7,8]. The surgical margin was microscopic positive in 21.6% in our series, which is comparably lesser than the literature where it varies between 13 and 52% (Table 1) A significant proportion of the tumors with soft tissue extension of the tumor in our series provide an indirect evidence of advanced nature of the osteosarcomas of our patient cohort.

A comparison of the major variables across the various series and meta-analysis is presented in Table 2 [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. The National Cancer Database (NCDB) of osteosarcomas suggests that the survival and prognosis of the head and neck osteosarcomas lie midway as compared to the other sites of occurrence, the best survival noted in is upper extremity, while the poorest survival is noted in the pelvic region [23]. In contrast, a vast majority of the head and neck osteosarcomas in the pediatric population are typically low to intermediate grade lesions, predominantly occurring in the mandible with an excellent overall long-term prognosis [29]. Local recurrences predominate in osteosarcoma of the head and neck with a reported incidence of 17–70% compared with 5–7% in extremity osteosarcoma [4, 9]. On the contrary, distant metastases are observed less often than with the more common osteosarcomas arising in the long bones, nevertheless; a consideration for metastasectomy for systemic recurrence should be made whenever feasible as this can possibly have a positive impact on survival. The 5-year OS of osteosarcomas of head and neck region in our series was 47.6%, which was found to be higher than the 5 year OS of the meta-analysis which was at 37% [28].

The influence of the various prognostic factors affecting the survival outcomes has not been widely studied because of scarce data. Adverse outcomes has been noted for tumors >6 cm, age of >60 years, a non-mandibular tumor location, an osteoblastic histological type, an advanced disease stage, non-surgical initial therapy and a positive margins of resection [23, 30]. Soft tissue extensions are found to be an adverse prognostic factor in a few studies [26, 31]. The meta-analysis by Kassir et al. [28] showed extra-gnathic tumors faring much worse; however, there was no difference in survival noted between the sub-sites of mandible or maxilla. A recent retrospective study of 160 patients of head and neck osteosarcomas showed that histological grade and unclear margins were significantly independent prognostic factors affecting the surviving outcomes [30]. Among all the factors analyzed in our cohort of patients, only surgical margin status seemed to have a bearing on the survival outcomes.

An Indian study from has provided insights with regards to the role of adjuvant radiation in head and neck osteosarcomas. The authors stated that that adjuvant radiation improved the local control in patients with adverse prognostic factors, more so in patients with close/positive margins [27]. Our series suggested a trend for better survival with the use of adjuvant external beam radiation therapy, with or without chemotherapy; however, this trend was not statistically significant (Table 3). A consideration for adjuvant radiation should be made for patients in whom the tumors were resected with close/positive margins [32] and other adverse prognostic factors [27].

There is an ongoing debate about the value of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in the management of head and neck osteosarcomas. It is prudent to mention that in head and neck osteosarcomas the response to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy is difficult to appreciate both clinically and radiologically, and moreover the response to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy is lesser than the extremity osteosarcomas on pathological assessment [22]. The meta-analysis of non-randomized studies found no benefit for chemotherapy and actually reported a worse outcome for patients treated with chemotherapy [28]; however, several other authors have reported to the contrary, stating that neo-adjuvant chemotherapy helps by improving local control, by decreasing the incidence of lung metastases and also by prolonging the time to development of lung metastases [33, 34]. In our series, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy was administered in three cases wherein upfront surgery with negative margins was deemed not possible. A few case series have reported that after adjusting for surgical status, no significant effects were noted for neo-adjuvant chemotherapy when compared with adjuvant chemotherapy [18, 22]. The role of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in head and neck osteosarcomas is evolving and presently not clearly defined [32]. Despite the lack of evidence, many authors do advocate the use of chemotherapy, especially in the presence of adverse factors.

The limitation of our study was the modest numbers, heterogeneity in treatments and the retrospective nature of the study which precludes us from making any firm recommendations. However, although it is common knowledge, our series does highlight the importance of performing a wide excision with microscopically negative margins, margin positivity in fact was the single factor that predicted an adverse outcome. Further, we do hope that the review of existing sparse literature will help clinicians in taking better informed decisions with regard to the clinical management of head and neck osteosarcomas.

Conclusion

Osteosarcoma of the head and neck region is a rare malignant bone tumor that occurs primarily in the jaw, with a unique biology and seems to have a more aggressive clinical course when compared to its counterparts in the extremities. The optimal treatment is surgery which entails a wide excision with microscopically negative margins. Adjuvant external beam radiation therapy should be considered for patients with close or positive margins and other adverse prognostic factors. The role of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy is ill-defined and is evolving. Although our series is small, it does highlight the importance of achieving a margin-negative resection. Considering the relative paucity of data, there is a need for multi-institutional collaborative studies to refine the therapeutic strategies for the management of patients with head and neck osteosarcomas.

References

Lim S, Lee S, Rha SY, Rho JK (2016) Cranofacial osteosarcoma: single institutional experience in Korea. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 12:e149–e153

Sturgis EM, Potter BO (2003) Sarcomas of the head and neck region. Curr Opin Oncol 15:239–252

Clark JL, Unni KK, Dahlin DC, Devine KD (1983) Osteosarcoma of the jaw. Cancer 51:2311–2316

Guadagnolo BA, Zagars GK, Raymond AK, Benjamin RS, Sturgis EM (2009) Osteosarcoma of the jaw/craniofacial region. Cancer 115:3262–3270

Jasnau S, Meyer U, Potratz J, Jundt G, Kevric M, Joos UK et al (2008) Craniofacial osteosarcoma experience of the cooperative German–Austrian–Swiss osteosarcoma study group. Oral Oncol 44:286–294

Mark KJ, Sercarz JÁ, Tran L, Dodd LG, Selch M, Calcaterra TC (1991) Osteosarcoma of the head and neck. The UCLA experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 117:761–766

Bertoni F, Dallera P, Bacchini P, Marchetti C, Campobassi A (1991) The Instituto Rizzoli–Beretta experience with osteosarcoma of the jaw. Cancer 68:1555–1563

Junior AT, Alves FAD et al (2002) Head and neck osteosarcomas—a review of the literature. Braz J Oral Sci 1:112–115

Canadian Society of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Oncology Study Group (2004) Osteogenic sarcoma of the mandible and maxilla: a Canadian review (1980–2000). J Otolaryngol 33:139–144

Nissanka E, Amaratunge E, Tilakaratne W (2007) Clinicopathological analysis of osteosarcoma of jaw bones. Oral Dis 13:82–87

Dickens P, Wei WI, Sham JST (1990) Osteosarcoma of the maxilla in Hong Kong. Chinese postirradiation for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer 66:1924–1926

Bennett JH, Thomas G, Evans AW, Speith PM (2000) Osteosarcoma of the jaws: a 30-year retrospective review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 90:323–333

Mardinger O, Givol N, Talmi Y, Taicher S (2001) Osteosarcoma of the jaw: the Chaim Sheba Medical Center experience. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 91:445–451

Clark J, Unni K, Dahlin D, Devin K (1983) Osteosarcoma of the jaw. Cancer 51(2311–231):6

Saito K, Unni K (1999) Osteosarcoma of the jaw bones. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 28(Suppl. 1):34

Nachman J, Simon MA, Dean L, Shermeta D, Dawson P, Vogelzang NJ (1987) Disparate histological responses in simultaneously resected primary and metastatic osteosarcoma following intravenous neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 5:1185–1190

Wozniak W, Rychlowska M, Liebhart M, Klepacka T, Poznanska A (1993) Preliminary estimation of prognostic factors in osteosarcoma in children on the basis of treatment results. Med Paediatr Oncol 21:596

Smeele LE, van der Wal JE, van Diest PJ, van der Waal I, Snow JB (1994) Radical surgical treatment in craniofacial osteosarcoma gives excellent survival. A retrospective cohort study of 14 patients. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 30:374–376

Van Es RJ, Keus RB, van der Wall I, Koole R, Vermey A (1997) Osteosarcoma of the jaw bones. Long-term follow up of 48 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 26:191–197

DeAngelis AF, Spinou C, Tsui A, Iseli T et al (2012) Outcomes of patients with maxillofacial osteosarcoma: a review of 15 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 70:734–739

Baghaie F, Motahhary P (2003) Osteosarcoma of the jaws: a retrospective study. Acta Med Iran 41:113–121

Patel SG, Meyers P, Huvos AG et al (2002) Improved outcomes in patients with osteogenic sarcoma of the head and neck. Cancer 95:1495–1503

Smith RB, Apostolakis LW, Karnell LH, Koch BB, Robinson RA (2003) National cancer data base report on osteosarcoma of the head and neck. Cancer 98:1670–1680

Ha PK, Eisele DW, Frassica FJ, Zahurak ML, McCarthy EF (1999) Osteosarcoma of the head and neck: a review of the Johns Hopkins experience. Laryngoscope 109:964–969

Durnali A, Alkis N, Yukruk FA, Dikmen AU, Akman T et al (2014) Osteosarcoma of the jaws in adult patients: a clinico pathological study of 14 patients. Sarcoma Res Int 1:4

Oda D, Bavisotto LM, Schmidt RA, McNutt M, Bruckner JD, Conrad EU III et al (1997) Head and neck osteosarcoma at the university of Washington. Head Neck 19:513–523

Laskar S, Basu A et al (2009) Osteosarcoma of the head and neck region: lessons learned from a single-institution experience of 50 patients. Head Neck 30:1020–1026

Kassir RR, Rassekh CH, Kinsella JB, Segas J, Carrau RL, Hokanson JA (1997) Osteosarcoma of the head and neck: meta-analysis of nonrandomized studies. Laryngoscope 107:56–61

Gadwal SR, Gannon FH, Fanburg-Smith JC, Becoskie EM, Thompson LD (2001) Primary osteosarcoma of the head and neck in pediatric patients: a clinicopathologic study of 22 cases with a review of the literature. Cancer 91:598–605

Chen Y, Shen Q, Gokavarapu S, Lin C, Yahiya Cao W, Chauhan S, Liu Z, Ji T, Tian Z (2016) Osteosarcoma of head and neck: a retrospective study on prognostic factors from a single institute database. Oral Oncol 58:1–7

Granados-Garcia M, Luna-Ortiz K, Castillo-Oliva HA et al (2006) Free osseous and soft tissue surgical margins as prognostic factors in mandibular osteosarcoma. Oral Oncol 42:172–176

Mendenhall WM, Fernandes R, Werning JW, Vaysberg M, Malyapa RS, Mendenhall NP (2011) Head and neck osteosarcoma. Am J Otolaryngol 32:597–600

Boon E, van der Graaf WT, Gelderblom H, Tesselaar ME, van Es RJ, Oosting SF et al (2017) Impact of chemotherapy on the outcome of osteosarcoma of the head and neck in adults. Head Neck 39:140–146

Mücke T, Mitchell DA, Tannapfel A, Wolff KD, Loeffelbein DJ, Kanatas A (2014) Effect of neoadjuvant treatment in the management of osteosarcomas of the head and neck. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 140:127–131

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standard

All procedures performed in this report were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krishnamurthy, A., Palaniappan, R. Osteosarcomas of the Head and Neck Region: A Case Series with a Review of Literature. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 17, 38–43 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12663-017-1017-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12663-017-1017-8