Abstract

While a growing number of high school students in the United States have experienced trauma exposure, there is a lack of review of studies that examine the efficacy of trauma-informed high schools. The current systematic review sought to identify reviews of empirical studies that explore the efficacy of trauma-informed approaches in high schools. The Evidence for Policy and Practice (EPPI-Center) framework was used to analyze the quality of literature identified including research design, participants, nature of intervention, method of analysis, and study outcomes. Analysis indicated studies about trauma-informed high schools are in their infancy. Methodological designs were limited, participants were skewed towards adults, and outcomes were specific and not generalized. Indeed, half of the studies focused on teachers alone rather than student outcomes. The small number of existing reviews and studies, and the diversity of study aims and designs, made it difficult to generalize outcome results. Further empirical research is needed on the efficacy of trauma-informed high schools that include more robust research designs as well as students and other stakeholders as participants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Trauma, a psychological reaction to an event, can result from bullying, community violence, domestic violence, or disasters. Children and adolescents who experience trauma may have difficulty sleeping, feel physical or emotional distress, and have difficulty learning (National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2013). The NCTSN (n.d.) succinctly defines trauma as “When a child feels intensely threatened by an event he or she is involved in or witnesses.” Despite its simple definition, trauma has a variety of repercussions that can come from a myriad of sources, including an adverse childhood experience (ACE). The first ACE survey was conducted in 1997. This study revealed that 64% of the 17,000 participants, who were adults, had at least one ACE. Almost 20 years later 13 percent of children have been exposed to multiple ACEs (Beal et al., 2019; Evans & Evans, 2019). Reporting also shows that two-thirds of children under the age of 16 in the United States are exposed to a traumatic event, and one-third of children are likely to experience physical abuse, while one in four girls and one in five boys experience sexual victimization during childhood (D’Andrea et al., 2011; NCTSN, 2013). In short, significant evidence exists to suggest many school aged children and adolescents are exposed to trauma every year.

Consequences of trauma exposure on the developing adolescent brain can be enduring (Coleman, 2019; Romeo, 2013). While single event and small cluster trauma can lead to posttraumatic stress disorder and the comorbidity of anxiety and depression, adolescents experiencing the complex trauma exposure of abuse and neglect can develop pervasive symptoms of developmental trauma disorder (DTD; van der Kolk, 2005). DTD also includes problems with dissociation, somatic symptoms and physical illness, relationships difficulties in the home, school and community, self-harm, suicidal ideation/suicide, criminality, and reduced employment opportunities. A wide range of difficulties have also been reported in schools (Perfect et al., 2016). These include challenges with attention, executive functioning, learning, and relationships. For adolescents who drop out of school or are placed within residential establishments the DTD rate can be as high as ninety percent (Barron et al., 2017).

In the high school setting, the negative effects of trauma exposure can be far reaching and overwhelming. Students who have experienced trauma may have one or more academic challenges that range from lower attention spans, less ability to concentrate, and poorer organizational skills, to school avoidance and failing grades, to diagnosed disabilities and behavioral challenges which turn into disciplinary referrals and lead to school suspension (Bilias-Lolis et al., 2017; Brunzell et al., 2016; Cole et al., 2005; Tishelman et al., 2010; Wamser-Nanney & Vandenberg, 2013). Children who have suffered trauma are likely to have academic difficulties.

A key purpose of schooling in the United States is to prepare students to become good citizens (Labaree, 1997). To achieve this objective, students must be able to learn. Additionally, schools receive funding from the federal government based on the results of standardized testing (McDonnell, 2015). The need for funding can manifest into teachers creating pressure for students to score well on standardized tests. Yet there are a large number of students attending public schools in the United States who have been exposed to at least one traumatic event (Beal et al., 2019). This creates a need for schools to be able to teach students who are victims of trauma. Although there appears to be a rapid growth in the number of trauma-informed approaches in schools in 17 states (Overstreet & Chafouleas, 2016), there is little evidence on how schools define adolescent traumatization, how they respond in trauma-specific ways to support youth, and the costs involved in such developments (Berliner & Kolko, 2016). Training and support however, have been recommended for school staff in trauma-informed approaches (Howard, 2018).

In response to the significant increase and continued growth in the delivery of trauma-informed approaches in education settings at local and national levels, Maynard and colleagues’ (2019) conducted a systematic review to identify the impact of such approaches on student behavior, wellbeing, and academic achievement to inform policy and practice. The recent Campbell Collaboration systematic review of trauma-informed approaches in schools across all ages, found only a few studies and those identified failed to reach the review inclusion criteria (Maynard et al., 2019). The authors concluded that no studies currently met the stringent criteria (randomized control trial or quasi-experimental designs with comparison groups) for inclusion in the Campbell Collaboration review. A further difficulty was the multiplicity of language and lack of consensus to label schools program implementation, for example trauma-informed, trauma sensitive, and trauma informed care or system (Hanson & Lang, 2016). This lack of cohesion further complicated a systematic review. Consequently, questions regarding the definition of trauma-informed approaches, their costs, benefits, and risks of implementation could not be answered. The current review, in contrast then, adopted a more inclusive approach to research design. The intention is to better assess the literature by including more studies, with various approaches, that examine the problem.

This review, which includes studies up to 2020, focused specifically on high schools and used more inclusive criteria to explore study design and findings. Key words initially included “depression,” “anxiety,” “PTSD,” and then included “trauma” and “high school.” The current review uses the term trauma-informed high schools as defined by the NCTSN (n.d.b), that is, “all parties involved recognize and respond to the impact of traumatic stress on those who have contact with the system, including children, caregivers, and service providers. Programs and agencies within such a system infuse and sustain trauma awareness, knowledge, and skills into their organizational cultures, practices, and policies. They act in collaboration with all those who are involved with the child, using the best available science, to facilitate and support the recovery and resiliency of the child and family” (Creating Trauma-Informed Systems). The current review, therefore, enables an analysis of the types of studies conducted, their limitations, and tentative outcomes to identify future research questions.

Given the number of adolescents who experienced trauma, and the lack of review of studies and findings, it seems important to synthesize the literature for schools in order to raise awareness of adolescents’ traumatic experiences, the social, emotional, health, and economic consequences of exposure as well as to understand the most cost-effective ways to respond. The current authors suggest educators need to be able to identify students who have experienced trauma and the most effective pedagogy and learning environment for teaching those students. This review, therefore, sought to examine the literature about trauma-informed schools, analyze the findings, and identify effective interventions to determine how best to respond to traumatized adolescents in high schools.

Methodology

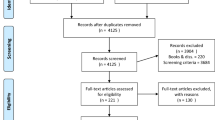

Given the pervasive nature of complex trauma in the adolescent population and the lack of synthesis of studies, the current review aimed to analyze empirical studies on the efficacy of trauma-informed high schools in the United States. The current review included empirical studies focused on determining the efficacy of high schools in addressing adolescents with trauma, excluded literature reviews, included adolescents or teachers as participants, and were written in English and dated between 2010 to 2020. Because of the paucity of published studies, the current review included grey literature in order to identify potential future research questions. The review also used the Evidence for Policy and Practice (EPPI-Center, 2007) framework, a common approach within educational reviews, to systematically analyze the studies. The framework provided a systematic approach to identify conceptual and empirical goals for future research as well as synthesize empirical evidence for those who work with traumatized high school students. The authors selected the EPPI framework for this review for a number of reasons. First, EPPI has been used extensively within education studies, including those that focus on student well-being. Secondly, EPPI provides a protocol to (a) systematically search the literature, (b) synthesize study findings, (c) appraise quality and relevance of studies, and (d) draw conclusions and make recommendations. Such an approach aids reliability and generalizability. Finally, EPPI, is a pragmatic approach, designed to facilitate the use of research evidence for developing policy and practice guidelines.

The application of EPPI involved the following phased analyses: (i) the broad aim(s) of the study, why it was conducted, the context of the study; (ii) the research questions, and the topic focus of the study; (iii) the appropriateness of the research strategy to the design and research question(s); (iv) type of study, the setting, and the location; (v) the intervention/program evaluated; (vi) the nature of the analysis; (vii) the context and consistency of reporting the results; (viii) whether any differentiation between the results and the conclusions existed and that conclusions followed from results; and finally, (ix) limitations and generalizability.

The literature search was conducted through ProQuest, ERIC, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Search terms included: anxiety, depression, learning, teaching, PTSD, dissociation, high school, trauma-informed school, trauma-informed education, trauma-informed systems, and trauma informed care in education. This resulted in 43 possible papers to study. The review excluded papers that studied elementary or middle school students, took place in a residential facility, did not focus on trauma, studied non-school settings, were not research papers or took place outside of the United States. Of the identified papers, this review included nine empirical studies for analysis.

Results

The review aimed to identify and analyze the quality and outcomes of empirical studies that evaluated trauma-informed interventions in high schools. Table 1 provides an overview of the study design, population, location and intervention of the studies. Table 2 offers an overview of the measures, analysis, delivery, outcomes of the same studies. The studies ranged in aims from identifying students with trauma, creating trauma-informed responses to discipline, and articulating specific methods for working with students with trauma. The nine studies used for this review, all dated between 2016 to 2020, included five published papers (Baroni et al., 2020; Blitz & Mulcahy, 2017; Buxton, 2018; Franco, 2018; Kataoka, 2018), three Doctoral dissertations (Goodwin-Glick, 2017; Haas, 2018; Taytslin, 2016), and one Master’s thesis (Waibel, 2017).

Research Design

The studies included a range of research designs. Baroni et al. (2020), Goodwin-Glick (2017), Haas (2018), and Taytslin (2016) used quasi experimental designs. Haas (2018) and Taytslin (2016) asked qualitative questions about the participants’ beliefs and practices based on the interventions experienced. Goodwin-Glick (2017) used a retrospective quantitative study design to ask questions after the intervention was complete about participants’ beliefs before and after participating in professional development (PD). Baroni et al. (2020) compared suspension rates before and after an intervention. Buxton (2018) used a retrospective document analysis design reviewing student records. Blitz and Mulcahy (2017) used a community based participatory research (CBPR) design, and Franco (2018), Kataoka et al. (2018), and Waibel (2017) utilized case study designs. Research designs were varied.

Population Sample and Study Locations

Studies were characterized by a variety of populations. They varied in size, location, and participants. Most of the studies included small sample sizes and included fewer than 35 participants, whether they were professional staff or students (Buxton, 2018; Franco, 2018; Haas, 2018; Taytslin, 2016; Waibel, 2017). Franco (2018) had a single participant, while Goodwin-Glick (2017) targeted 500 participants, and Kataoka et al. (2018) studied three schools in a large urban setting. Five of the researchers did not articulate how they recruited their participants, while four used samples of convenience. Half of the researchers stated they recruited participants based on a relationship with the school where the study took place (Buxton, 2018; Goodwin-Glick, 2017; Haas, 2018; Waibel, 2017), two sets of researchers were presumed to have relationships with the organizations (Blitz & Mulcahy, 2017; Kataoka et al., 2018), while the others did not specify how they recruited their participants (Baroni et al., 2020; Franco, 2018; 2018; Taytslin, 2016). Adults made up the majority of participants, often participating in PD, while four of the studies worked with students (Baroni et al., 2020; Franco, 2018; Kataoka et al., 2018; Waibel, 2017). Goodwin-Glick (2017) included non-professional staff members, such as school bus drivers, cafeteria workers, and paraprofessionals; the other studies focused primarily on teachers. The locations of the studies spanned seven different U.S. states. Blitz and Mulcahy (2017) purposely did not state where the study took place. Almost half of the studies occurred in urban settings. The studies shared little commonality between the sites. Studies, therefore, ranged in sample size, study location, and participant recruitment.

Intervention

More than half the studies included PD as the intervention, whether PD solely or one part of the intervention. The other studies, bar one, included using a trauma-informed alternative to suspension, implementing a trauma-informed curriculum, and using trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy (TF-CBT) (Baroni et al., 2020; Franco, 2018; Waibel, 2017). Except for Buxton (2018) who conducted a record review, researchers either worked with staff who used an intervention that increased the participants’ knowledge about trauma-informed care in schools or directly with students using a trauma-informed approach.

Duration of Intervention

The length of the interventions varied across the studies. One study gathered data based on six hours of PD delivered over two sessions (Goodwin-Glick, 2017), while another conducted research over three years (Baroni et al., 2020). Two studies did not report on the duration of the intervention (Buxton, 2018; Kataoka et al., 2018). The other studies involved four sessions of PD (Haas, 2018), PD delivered over summer vacation (Taytslin, 2016), and studying a student over the course of a year (Franco, 2018). The duration of intervention across the studies varied as widely as the focus and the participants.

Measures

The five researchers who provided PD directly to staff used a variety of surveys to measure their results (Blitz & Mulcahy, 2017; Goodwin-Glick, 2017; Haas, 2018; Taytslin, 2016). Taytslin (2016) developed a quantitative survey to conduct with all participants, and prepared for qualitative interviews for the experimental group; Blitz and Mulcahy (2017) used surveys as part of CBPR. Waibel (2107), who worked with students, used a qualitative questionnaire. Five studies used trauma lenses or trauma frameworks as a method to examine their data (Buxton, 2018; Franco, 2018; Goodwin-Glick, 2017; Kataoka et al., 2018; Waibel, 2017). Kataoka et al. (2017), who examined different settings within a school district, described various components of a trauma-informed care model as they were applied to different parts of a school system. Their study encompassed a more diverse population than the other studies because they included students, staff, and community members across various buildings within a public-school district. Therefore, their measures differed from the other studies (Kataoka et al., 2017). Most of the quantitative data collected included pre and post short-term interventions (Blitz & Mulcahy, 2017; Goodwin-Glick, 2017; Haas, 2018; Taytslin, 2016; Waibel, 2017). Only one study used quantitative measures over multiple years (Baroni et al., 2020). In short, the overwhelming majority of studies used qualitative rather than quantitative measures.

Nature of Analysis

The research conducted was analyzed through a mix of qualitative and quantitative approaches. Four studies used quantitative analysis only (Baroni et al., 2020; Buxton, 2018; Goodwin-Glick, 2017; Haas, 2018). Buxton (2018) analyzed the record review using a tool she constructed that measured the behavioral responses in individual education programs (IEPs), measuring intra-observer reliability through the kappa statistic. Goodwin-Glick (2017) and Haas (2018) conducted t-tests, and the former used descriptive statistics as part of her analysis. All three researchers analyzed the measures for reliability (Buxton, 2018; Goodwin-Glick, 2017; Haas, 2018). Baroni et al., (2020) used frequencies, descriptive statistics, and bivariate analysis to analyze their data and used the binary regression model using the Hosmer and Lemeshow test suggesting good fit.

Two studies used both quantitative and qualitative analysis to study the data. Blitz and Mulcahy (2017) used Cronbach alpha to analyze their initial questionnaires and then content analysis method to code data thematically from the focus groups to organize findings which dictated the direction of the work groups which resulted in CBPR. Taytslin (2016) intended to use both qualitative and quantitative analyses but did not get sufficient participants for a control group resulting in the use of participant interviews only. Taytslin (2016) coded the interviews thematically for patterns between participants.

The final three studies used qualitative analysis alone to study the data (Franco, 2018; Kataoka et al., 2018; Waibel, 2017). Franco (2018) used qualitative descriptions of the intervention provided, using a case study to examine the effectiveness of CF-CBT. Kataoka et al. (2018) used narratives to highlight the successes and challenges of trauma-informed care models. Finally, Waibel (2017) used the constant comparative analysis to identify meanings from the data. In short, three-quarters of the researchers used qualitative analysis at least for some of the data analysis, while twenty-five percent used quantitative methods alone.

Study Outcomes

As with the noted sundry of research designs, methods and analyses, study outcomes also varied. Kataoka et al. (2018), in identifying positive outcomes from case studies, reported that a school closing the gap on standardized test scores correlated with the principal supporting trauma education for educators. They concluded that it is possible to implement trauma-informed programs and responses at different levels of public schools. Similarly, Baroni et al. (2020) found a decrease in out-of-school suspensions after using the Monarch Room model. They reported only one suspension in the third year of observation, compared with 27 the previous year. Goodwin-Glick (2017), Haas (2018), and Taytslin (2016) all experimented with PD and trauma-informed schools and, to some extent, reported positive outcomes. Goodwin-Glick (2017) reported increases in knowledge, disposition, and staff behavior. She found a large effect size for professionals recognizing signs of trauma symptoms, and a medium effect size for PD in a sample size of 542. Within the disposition category, she found a medium effect for the subscale of perspective taking, meaning staff were more willing to examine students’ point of view instead of making assumptions about them. Finally, Goodwin-Glick (2017) saw a medium effect in staff’s responses about their behavior towards students with trauma. Specifically, there were gains in staff reporting they are aware and mindful of their interactions with students as well as utilizing strategies to create safe spaces for students (Goodwin-Glick, 2017). Haas (2018), similarly, found the impact of PD on school personnel’s increased awareness of student trauma was statistically significant. The dissertation also noted significant change in participants’ beliefs and understanding of the impact trauma has on students and that schools had plans to develop schoolwide trauma-informed practices. Changes in practice, however, both schoolwide and in the classroom, had much smaller effects. Taytslin (2016) reported that PD had positive impact on teachers. The six participants reported increases in their knowledge and practice as a result of taking a training about trauma-informed education. They reported that they better understood trauma in their students thereby increasing their ability to adjust their teaching practices in response. Finally, the teachers reported an increase in self confidence in working with students with trauma (Taytslin, 2016). Blitz and Mulcahy (2017) reported that, following PD, teachers were better able to respond to the social, emotional, and behavioral needs of their students. However, through their participatory research, they learned that teacher stress increased at the same time their responses improved (Blitz & Mulcahy, 2017). Overall, the researchers found PD and training had a positive impact on working with students with trauma.

The other studies examined different aspects of working with students with trauma. Buxton (2018) examined 12 IEPs and found that 83 percent included indicators for three of the four functional domains often identified with trauma. IEPs were aligned with difficulties in academics, self-regulation, and relationships; she found no evidence of difficulty in physical functioning (Buxton, 2018). Another study with a small sample size was Waibel (2017), who taught five students in an afterschool program, and reported a positive impact. Students conveyed that they felt safer, and built better relationships with teachers, as a result of experiencing a curriculum focused on identity (Waibel, 2017). Finally, the student Franco (2018) studied subsequently attended an intervention group, received outside therapy, and experienced a safe support system. Franco (2018) reported the student improved in school as evidenced by a greater effort in class, more consistent attendance, and no longer sleeping in class. In summary, participant subjective experience indicated progress, whether teachers experiencing PD or adolescents experiencing curriculum and/or support.

Discussion

The current review found that studies into the efficacy of trauma-informed high school approaches are in their infancy. The small number of studies available for analysis are characterized by their diversity. Variability in research design, population, interventions and their duration, evaluation measures, nature of analysis and outcomes for students and staff appears the norm. The only consistency in the available studies is their inconsistency. Given the limited number of studies and high levels of variability in approach, generalization of study findings is premature at this time.

Research designs fit into three main categories: case studies, quasi-experimental, or other. One-third of the reviewed studies fit into each category: case studies (Franco, 2018; Kataoka et al., 2017; Waibel, 2017); quasi-experimental (Goodwin-Glick, 2017; Haas, 2018; Taytslin, 2016). Other included a longitudinal study (Baroni et al., 2020), a records review (Buxton, 2018), and CBPR (Blitz & Mulcahy, 2017). Research design, is therefore at mostly an exploratory level with little ability to assess the efficacy of interventions.

The diversity of study settings can be understood as both a strength and a weakness. The range of settings makes it difficult to generalize the efficacy of interventions on the one hand, but also highlights the presence of traumatized children requiring intervention in a wide range of school settings, on the other. Sites varied from suburban to urban schools, small to large schools, and one to multiple buildings within a district. The data consistently evidenced significant numbers of trauma-exposed students requiring support. Unfortunately, the diversity of studies undermines the extent to which conclusions can be made about the impact of trauma-informed approaches across these differing settings. What can be concluded is that trauma-exposed high school students are present in a variety of settings across the US, and rigorous research designs need to explore and compare the efficacy of interventions across setting and context.

Perhaps, not surprisingly, given the lack of rigor in research design, few studies assessed the validity/reliability of their measures. Only three studies, for example, tested for internal reliability (Buxton, 2018; Goodwin-Glick, 2018; Haas, 2017). All three studies, however, found a reasonable level of reliability. Blitz and Mulcahy (2017) sought to ensure the language used in questionnaires developed by the principal investigator (PI) and school personnel resonated with respondents. The PI adopted language used in the school for gathering and analyzing data. Waibel (2017) created questionnaires for teachers to respond to in comparison to student responses, however Waibel failed to report the process for creating or using the questionnaire. Given the disparate measures used and the lack of assessing validity and reliability, it is suggested that future research needs to utilize consistent standardized measures with known validity and reliability across studies in order to be confident in identifying significant outcomes for students in high schools.

Interventions also ranged widely, targeting different types of participant needs. Interventions varied from PD to curriculum which addressed students’ identity. Some studies focused on the school personnel to implement the intervention, whether a classroom teacher, school psychologist, or administrator (Goodwin-Glick, 2017; Haas, 2018; Kataoka et al., 2018; Taytslin, 2016). Although the current review indicates that many potential interventions are available, it also highlights the significant need to rigorously evaluate the efficacy of these interventions to determine which programs are more effective with which populations and contexts. Studies currently lack sufficient focus and rigor to provide such information. Significantly more research, therefore, is needed to address these complex questions. An argument could be made that future research needs to be similar to Baroni et al. (2020): less diverse in focus and evaluate trauma-specific interventions in the high school setting. Specifically, there is a need to develop protocols to determine which intervention is appropriate, given the population and the setting. Future studies also should explore interventions of similar nature and length and target the same type of participants. Future research needs to include more robust experimental quantitative research designs and data analyses to assess the impact students with trauma have on an entire school, the extent of gains and/or unintended negative consequences, and the cost-benefits in delivering the program. Despite the limited quality and diversity of research design, it would appear results indicate trauma-informed education for professionals and adolescents may be promising, however, there is a need for considerably more research to assess the specificity and size of these gains. There is also a need to assess whether there are any unintended negative consequences of trauma-informed high schools. Finally, there is a need to determine the cost of these approaches to enable high schools to make value for money judgments based on promising efficacy results.

Another weakness of the studies, is that most focused on adults. Half of the studies focused on PD and helping educators to learn about trauma and trauma-informed practices (Blitz, 2017; Goodwin-Glick, 2017; Haas, 2018; Taytslin, 2016). Only four studies focused on students’ outcomes including sense of safety, attendance, behavior, trauma symptoms, identity formation and communication (Baroni et al., 2020; Buxton, 2018; Franco, 2018; Waibel, 2017). Although all studies indicated progress in these outcomes, research designs’ insufficiency could not effectively indicate causation. Further, most studies had small sample sizes making it impractical to generalize findings (Buxton, 2018; Franco, 2018; Waibel, 2017). In theory, it is understandable that interventions are focused on the adults working with students. Adult knowledge and understanding of trauma should be a precursor for working with students with trauma. However, these research questions do not address the impact of teacher learning on student traumatization, learning and behavior. A similar pattern of research, where the focus is adults rather than adolescents, is found in wider social and emotional learning research studies (Lemkin et al., 2019; Morinaj & Hascher, 2019; Muratori et al., 2019). However, unlike trauma-informed high school research, there is now a growing number of studies that focus on interventions that address adolescent social emotional learning (Jayman et al., 2019; Low et al., 2019; Venta et al., 2019). It is hoped that trauma-informed high school research will follow this latter pattern with a focus on evaluating interventions with students and student outcomes.

When considering the research location, most researchers chose a site where they had a previous relationship. The positionality of the researchers might indicate a high level of bias. Potentially, participants could have responded affirmatively because of the researcher’s title, whether it is doctoral student, university professor, or building administrator, and subconsciously felt compelled to participate in the study. There existed the potential for teachers and counselors in CBPR to have felt obligated to participate because initial recruitment occurred in a faculty meeting where the principal expressed a positive attitude towards trauma-informed approaches (Blitz & Mulcahy, 2017). Although not mandated to participate, staff may have believed they had little choice because the principal was supportive and aligned with the researchers. Students may have agreed to participate in an afterschool program because of an affinity for teacher. Although not intending to, Waibel (2017) may have influenced students to agree to participate in her study because they liked her. Furthermore, they may have had a predisposition to being positive about the program (Waibel, 2017).

On the other hand, researchers may be more critical of positive outcomes because of the prior relationship. According to Rossman and Rallis (2012) undertaking research is “shaped by our personal interests and interpreted through our values and politics” (p. 117). Understanding the importance of creating effective trauma-sensitive schools may have led to results being more stringently examined. In other words, when there is a pre-established relationship, it could be imperative to implement what is deemed to be an effective intervention because of how much is perceived to be at stake. Bias may have occurred by school administrators at a school or district level where selection of a known researcher could be perceived as having deeper insights or because of anxieties about external researchers being more critical (Bhattacharya, 2017). In contrast, a ‘known’ researcher may be more accessible to conduct the study and prior relationships may engender more trust for disclosure (Rossman & Rallis, 2012). Practitioner knowledge of context may also lead to differing judgements being made about the research design, e.g., a bias towards qualitative and thick rich descriptive designs compared to more apparently objective quantitative approaches (Bhattacharya, 2017; Rossman & Rallis, 2012). Future quantitative research, however, needs to include independent researchers with greater objectivity. Additionally, blind and double-blind studies should be considered.

Conclusion

The disparate nature of focus, quality, and limitations of methodologies of the studies reviewed render it impossible to generalize on the efficacy of trauma-informed approaches within high schools. Empirical studies tended to focus on PD with adults as a means of creating or sustaining trauma-informed schools, rather than student outcomes. Overall, remarkably little commonality existed between the studies, programs and results. Considerable research involving rigorous research designs are needed to enable high schools to make informed decisions about what are the most cost-effective trauma-informed approaches.

Limitations

This review focused on the US high school education system rather than across childhood. Therefore, it excluded studies not focused on high schools. It is possible studies that included high school populations may have been overlooked if the title or abstract failed to reference high schools. Additionally, because this review focused on education in the United States, international studies which add to the literature on trauma-informed education may have been excluded. The EPPI-Centre (2007) while helpful for analysis, was not exhaustive and again, may have inadvertently excluded relevant studies.

Recommendations for Policy

Given the limited evidence, implications for policy are tentative and need further exploration. Schools need to not only identify potential empirically based programs but evaluate the delivery of these novel approaches within their own settings. Policies should be revised to not penalize students with trauma who have a trauma reaction as opposed to misbehaviors for other reasons. Zero tolerance policies, removal from classrooms for excessive absences, and office referrals in response to a trauma trigger should be examined at the school level.

Recommendations for Research

There is a need to conduct empirical research into the efficacy of trauma-informed approaches in high schools. Studies are needed to assess the impact in behavioral change following trauma-informed PD for high school teachers and the resultant impact on students. Empirical studies need to be more specific in the location of the study, including suburban and rural schools. Larger sample sizes are needed that are randomized and include more diverse and random populations. Finally, there is a need for studies to measure the cost-effectiveness of implementing trauma-informed approaches for high schools. Use of experimental designs and randomized control trials would be a significant step forward. The current review shows promise for future research. Given the various research sites, populations, and interventions, researchers interested in trauma-informed high schools have a myriad of options from which to build their studies. Any of the studies analyzed in this review could be a building block upon which the next study is based.

References

Baroni, B., Day, A., Somers, C., Crosby, S., & Pennefather, M. (2020). Use of the monarch room as an alternative to suspension in addressing school discipline issues among court-involved youth. Urban Education, 55(1), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916651321

Barron, I., Mitchell, D., & Yule, W. (2017). Pilot study of a group-based psychosocial trauma recovery program in secure accommodation in Scotland. Journal of Family Violence, 32(6), 595–606.

Beal, S. J., Wingrove, T., Mara, C. A., Lutz, N., Noll, J. G., & Greiner, M. V. (2019). Childhood adversity and associated psychosocial function in adolescents with complex trauma. Child & Youth Care Forum, 48(3), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-018-9479-5

Berliner, L., & Kolko, D. J. (2016). Trauma informed care: A commentary and critique. Child Maltreatment, 21(2), 168–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559516643785

Bhattacharya, K. (2017). Fundamentals of qualitative research: A practical guide. Routledge.

Bilias-Lolis, E., Gelber, N. W., Rispoli, K. M., Bray, M. A., & Maykel, C. (2017). On promoting understanding and equity through compassionate educational practice: Toward a new inclusion. Psychology in the Schools, 54(10), 1229–1237. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22077

Blitz, L. V., & Mulcahy, C. A. (2017). From permission to partnership: Participatory research to engage school personnel in systems change. Preventing School Failure, 61(2), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2016.1242061

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2016). Trauma-informed positive education: Using positive psychology to strengthen vulnerable students. Contemporary School Psychology, 20(1), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0070-x

Buxton, P. S. (2018). Viewing the behavioral responses of ED children from a trauma-informed perspective. Educational Research Quarterly, 41(4), 30–49. Retrieved from http://silk.library.umass.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/2044334861?accountid=14572

Cole, S., O’Brien, J., Gadd, M., Ristucca, J., Wallace, D., & Gregory, M. (2005). Helping traumatized children learn: Supportive school environments for children traumatized by family violence. Massachusetts Advocates for Children.

Coleman, J. (2019). Helping teenagers in care flourish: What parenting research tells us about foster care. Child & Family Social Work, 24(3), 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12605

D’Andrea, W., Sharma, R., Zelechoski, A. D., & Spinazzola, J. (2011). Physical health problems after single trauma exposure: When stress takes root in the body. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 17(6), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390311425187

Evans, C., & Evans, G. R. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences as a determination of public service motivation. Public Personnel Management, 48(2), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026018801043

Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre). (2007). EPPI-Centre methods for conducting systematic reviews. EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

Franco, D. (2018). Trauma without borders: The necessity for school-based interventions in treating unaccompanied refugees. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35, 551–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0552-6

Goodwin-Glick, K. (2017). Impact of trauma-informed care professional development on school personnel perceptions of knowledge, dispositions, and behaviors toward traumatized students (Order No. 10587819). Available From ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: Social Sciences. (1886086040). Retrieved from http://silk.library.umass.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.silk.library.umass.edu/docview/1886086040?accountid=14572

Haas, L. (2018). Trauma-informed practice: The impact of professional development on school staff. Available From Social Science Premium Collection. (2101893622; ED585010). Retrieved from http://silk.library.umass.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.silk.library.umass.edu/docview/2101893622?accountid=14572

Hanson, R. F., & Lang, J. (2016). A critical look at trauma-informed care among agencies and systems serving maltreated youth and their families. Child Maltreatment, 21(2), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559516635274

Howard, J. (2018). A systemic framework for trauma-aware schooling in Queensland. Research report for the Queensland department of Education.

Jayman, M., Ohl, M., Hughes, B., & Fox, P. (2019). Improving socio-emotional health for pupils in early secondary education with pyramid: A school-based, early intervention model. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12225

Kataoka, S. H., Vona, P., Acuña, A., Jaycox, L., Escudero, P.Stein, B. D. (2018). Applying a trauma informed school systems approach: Examples from school community-academic partnerships. Ethnicity and Disease, 28 (Supplement 2). Retrieved from http://apps.webofknowledge.com.silk.library.umass.edu/full_record.do?product=WOS&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=2&SID=5C4XK4ddOSAN4QlStWz&page=1&doc=2

Labaree, D. F. (1997). Public goods: The American struggle over educational goals. American Educational Research Journal, 34(1), 39–81.

Lemkin, A., Walls, M., Kistin, C. J., & Bair-Merritt, M. (2019). Educators’ perspectives of collaboration with pediatricians to support low-income children. Journal of School Health, 89(4), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12737

Low, S., Smolkowski, K., Cook, C., & Desfosses, D. (2019). Two-year impact of a universal social-emotional learning curriculum: Group differences from developmentally sensitive trends over time. Developmental Psychology, 55(2), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000621

Maynard, B. R., Farina, A., Dell, N. A., & Kelly, M. S. (2019). Effects of trauma-informed approaches in schools: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 15, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1018

McDonnell, L. M. (2015). Stability and change in title I testing policy. RSF The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 1(3), 170–186. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2015.1.3.09

Morinaj, J., & Hascher, T. (2019). School alienation and student well-being: A cross-lagged longitudinal analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(2), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-018-0381-1

Muratori, P., Lochman, J. E., Bertacchi, I., Giuli, C., Guarguagli, E., Pisano, S., & Mammarella, I. C. (2019). Universal coping power for pre-schoolers: Effects on children’s behavioral difficulties and pre-academic skills. School Psychology International, 40(2), 128–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034318814587

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (n.d.). Creating Trauma Informed Systems. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/trauma-informed-care/creating-trauma-informed-systems

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (2013). Understanding child trauma. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/resources/understanding-child-trauma-and-nctsn

Overstreet, S., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2016). Trauma-informed schools: Introduction to the special issue. School Mental Health, 8, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9184-1

Perfect, M., Turley, M., Carlson, J., Yohannan, J., & Gilles, M. (2016). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990–2015. Disabilities and Psychoeducation Studies, 27(8), 7–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2

Romeo, R. D. (2013). The teenage brain: The stress response and the adolescent brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(2), 140–145.

Rossman, G. B., & Rallis, S. F. (2012). Learning in the field: An introduction to qualitative research (3rd ed.). Sage.

Taytslin, A. J. (2016). Teacher experiences in response to training on safe and supportive schools (Order No. 10192502). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; Social Science Premium Collection. (1848669014). Retrieved from http://silk.library.umass.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.silk.library.umass.edu/docview/1848669014?accountid=14572

Tishelman, A. C., Haney, P., O’Brien, J. G., & Blaustein, M. E. (2010). A framework for school-based psychological evaluations: Utilizing a “trauma lens.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 3(4), 279–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361521.2010.523062

van der Kolk, B. A. (2005). Developmental trauma disorder: toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 401–408.

Venta, A., Bailey, C., Muñoz, C., Godinez, E., Colin, Y., Arreola, A., & Lawlace, S. (2019). Contribution of schools to mental health and resilience in recently immigrated youth. School Psychology, 34(2), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000271

Waibel, L. (2017). Applications of trauma-informed curriculum in the artroom to promote adolescent identity development. Available From ERIC. (1968431573; ED574853). Retrieved from http://silk.library.umass.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.silk.library.umass.edu/docview/1968431573?accountid=14572

Wamser-Nanney, R., & Vandenberg, B. R. (2013). Empirical support for the definition of a complex trauma event in children and adolescents. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(6), 671–678. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21857

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Carol Cohen performed the literature search and drafted the initial analysis. Ian Barron critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, C.E., Barron, I.G. Trauma-Informed High Schools: A Systematic Narrative Review of the Literature. School Mental Health 13, 225–234 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09432-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09432-y