Abstract

Childhood trauma can adversely impact academic performance, classroom behaviour, and student relationships. Research has gradually explored integrated approaches to care for traumatised students in schools. Increasingly, research has pointed to implementation of multi-tiered programs to trauma-informed care for traumatised students in schools. However, evaluations of these programs are limited and no systematic review of the existing evidence has been conducted. The aim of this research was to be the first systematic review to explore evidence on multi-tiered, trauma-informed approaches to address trauma in schools. Results of this systematic review yielded 13 published and unpublished studies. Findings indicated that further research, guided by empirical evidence of the effectiveness of multi-tiered and trauma-sensitive approaches in schools, is required. Recommendations for research in the area of trauma-sensitive, multi-tiered care in schools are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The relationship between trauma exposure and impaired school-related functioning, including behavioural issues, social and emotional concerns, and academic impairment, is well established. Trauma exposure in childhood is associated with lower academic achievement and test scores, lower IQ scores and impaired working memory, and delayed language and vocabulary (Perfect, Turley, Carlson, Yohanna, & Saint Giles, 2016). Traumatised students exhibit poorer attention, disruptive behaviours, aggression, hyperactivity and impulsivity, defiance, and school suspensions, absences and grade retention, as well as depression, anxiety, withdrawal, and low self-esteem (Perfect et al., 2016). Research has also found traumatised children with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) show greater school-related impairment compared to trauma-exposed children without PTSD (Weems et al., 2013). However, while research continues to demonstrate a link between school-related outcomes and trauma, the limited literature has explored the experiences of school staff and teachers in relation to traumatised children. Several studies have concluded that trauma-informed practices be implemented in schools to increase support for school staff, improve responses to traumatised children, and reduce behavioural and academic problems of students (e.g. Alisic, 2012; Alisic, Bus, Dulack, Pennings, & Splinter, 2012; Mendelson, Tandon, O’Brennan, Leaf, & Ialongo, 2015).

Studies with school teachers and students have found teachers’ experience uncertainty, lack competence, and have limited training and policy knowledge in relation to childhood trauma (Alisic, 2012; Alisic et al., 2012; Dyregrov, 2009; Dyregrov, Bie Wikander, & Vigerust, 1999; Kenny, 2001, 2004; Papadatou, Metallinou, Hatzichristou, & Pavlidi, 2002). Trauma-related confidence has been shown to relate to greater teaching experience, exposure to trauma-focused training, and involvement with traumatised children (Alisic et al., 2012). Other studies have documented secondary PTSD symptoms among school staff exposed to student trauma (Berger, Abu-Raiya, & Benatov, 2016; Bride, 2007; Smith Hatcher, Bride, Oh, Moultrie King, & Catrett, 2011). Following the 2011 Canterbury earthquake in New Zealand, Berger and Abu-Raiya et al. (2016) reported positive implications of a universal, school-based, resilience program in reducing teacher PTSD and secondary trauma, increasing self-efficacy and optimism, and improving coping of teachers. A universal, school-based, trauma-informed program for disadvantaged students was also found to improve students’ emotion regulation, social competence, academic performance, classroom behaviour, and authority acceptance (Mendelson et al., 2015).

An increasing number of studies have shown positive effects of school-based interventions for students with PTSD. The Cognitive Behavioural Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) and ERASE-Stress program have been reported to lower symptoms of PTSD and depression among students (Berger & Gelkopf, 2009; Jaycox et al., 2009). Teacher-mediated interventions have also had positive impacts on trauma-exposed children, including the Students Exposed to Trauma (SSET) program, adapted from the CBITS program (Jaycox et al., 2009), and programs developed in response to childhood exposure to war and disaster (Powell & Bui, 2016; Wolmer, Hamiel, Barchas, Slone, & Laor, 2011; Wolmer, Hamiel, & Laor, 2011). However, while a growing number of studies have shown the positive effects of school-based interventions related to trauma, little is known about integrated, multi-tiered systems of support to manage trauma in schools. Integration of trauma-sensitive programs within existing evidence-based frameworks is likely to increase the sustainability of school programs in response to student trauma (Chafouleas, Johnson, Overstreet, & Santos, 2016; Nadeem & Ringle, 2016).

Several multi-tiered ‘triangle’ or ‘pyramid’ prevention frameworks have been proposed for school mental health promotion. The School-wide Positive Behaviour Support (SWPBS; also known as school-wide PBS, positive behavioural interventions and supports [PBIS], and multi-tiered systems of support [MTSS]) framework is an evidence-based, three-tiered model of intervention, including Tier 1 for universal support of all students regardless of emotional or behavioural concerns (e.g. community-wide disaster exposure); Tier 2 for intensive secondary support with groups of students at risk or showing early signs of emotional or behavioural issues (e.g. directly witnessing or experiencing trauma); and Tier 3 for tertiary, intensive, and individualised intervention for students with significant emotional or behavioural problems (e.g. PTSD as a result of trauma exposure; Sugai & Horner, 2006; Weist et al., 2018). This three-tiered approach is also represented in other frameworks, including the response to intervention (RTI) model (IDEA, 2004), the Public Health Model for Mental Illness and Risk Behaviours (Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994), and, more recently, trauma-informed approaches for rural and disadvantaged students (Hansel et al., 2010; Stokes & Turnbull, 2016). However, better alignment of trauma-informed models within existing multi-levelled, school-based support systems has been suggested to increase delivery and fidelity of trauma-sensitive policies and practices in schools (Chafouleas et al., 2016; Phifer & Hull, 2016; Plumb, Bush, & Kersevich, 2016; McDermott & Cobham, 2014; Reinbergs & Fefer, 2018; Weist et al., 2018).

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the evidence and address the strengths and limitations of research regarding multi-tiered, trauma-informed interventions in schools. In particular, this review aims to highlight the growing literature concerning the practice of trauma-sensitive, multi-tiered treatment of students in schools, evaluate the design and methods used in evaluating these models, and provide recommendations for improved trauma-based research and program implementation in schools. Although case studies, literature and systematic reviews have been conducted (e.g. Fu & Underwood, 2015; Phifer & Hull, 2016; Price et al., 2012; Rolfsnes & Idsoe, 2011; Weist et al., 2018), this review will focus on evaluating the evidence on alignment of these approaches in schools. This review is timely based on recent suggestions for better clarification around methods for integrating trauma and positive behaviour approaches in schools (Zakszeski, Ventresco, & Jaffe, 2017). Greater understanding of alignment between trauma-informed approaches and tiered school-based intervention and support programs is anticipated to increase research for greater adoption of these approaches in schools. This will likely improve staff knowledge and confidence regarding trauma, increase the overall efficiency of schools in accommodating traumatised students, enhance students’ school engagement and academic achievement, and improve post-traumatic growth and recovery of trauma-impacted students.

Method

Search Strategy

The PRISMA protocol, Cochrane handbook and JBI scoping reviewers manual were used to inform this review. Six electronic databases (i.e. PsycINFO, Ovid MEDLINE, ERIC, A+ Education, Web of Science conference proceedings citation index—Science, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global) were used to search for the published and unpublished literature (i.e. conference proceedings and theses), written in English only, and using search terms such as trauma, disaster, violence, post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, multi-tiered, trauma-informed, positive behaviour support, PBS, response to intervention, RTI, and school. The inclusion of the published and unpublished literature, including theses and conference proceedings, was decided because this is a relatively new area of research. Because of this, no exclusions were also placed on the year of publication for perspective articles, and other published and unpublished materials. Inclusion of studies was those which referred to and provided evidence of a multi-levelled approach to trauma-sensitive care in schools, including intervention across teachers, parents and/or students. Therefore, articles referring to intervention within one tier of a multi-tiered model, such as evaluation of an indicated intervention for children identified with PTSD, were excluded from this review (e.g. Cohen et al., 2009; Jaycox et al., 2009). These programs have been reviewed extensively in the past (see, for example, Chafouleas, Koriakin, Roundfield, & Overstreet, 2019; Rolfsnes & Idsoe, 2011). Articles using qualitative and quantitative approaches, or a mixed methodology, were included to capture all the available literature in the area, as well as the literature across all levels of schooling from preschool to secondary school. Research conducted across specialist school settings (e.g. residential treatment centres) were excluded due to the Tier 3 treatment needs of these populations (e.g. one-on-one lessons and support; Day et al., 2015).

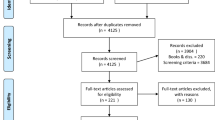

The search was conducted from March 2018 through May 2018. The search strategy procedure and outcomes are presented in Fig. 1. The initial search yielded 1018 results. Of the 1018 results, 265 were excluded as duplicates. All remaining 753 results underwent screening by title, with 408 excluded and 345 retained for screening by abstract. Excluded articles related to school violence and disruptive behaviour prevention, and other articles with no association to trauma. Screening by abstract revealed a further 171 records to be removed and 174 to be retained for screening by full text. Full-text records were then reviewed to reveal 10 results to be retained. The final excluded articles only evaluated one tier of school trauma interventions, or referenced other externalising and internalising disorders with no association made to trauma. These results were then subject to cited reference screening which yielded no records, and a Google Scholar search was conducted to identify an additional three records.

Studies excluded were those that dealt exclusively with school violence intervention, behaviour management practices, and other internalising and externalising problems (e.g. community violence and school bullying; Runge, Knoster, Moerer, Breinich, & Palmiero, 2017), as well as articles that described programs and their implementation, but did not evaluate the outcomes of these programs (e.g. McDermott & Cobham, 2014; Saltzman, Layne, Steinberg, Arslanagic, & Pynoos, 2003).

Data Extraction and Coding

Records were extracted by the author and coded according to the PICOS categories and additional variables, including (a) country where the study was conducted; (b) participant numbers and demographics; (c) type of trauma experienced (e.g. disaster, war, violence); (d) study design and measures; (e) type of intervention implemented; (f) tier levels included; (g) outcomes of the research; and (h) study limitations. Details of the identified studies are included in Table 1.

Results

Three-Tier Programs

Ten studies were identified as including three levels of intervention for trauma in schools (Cicchetti, 2017; Dorado, Martinez, McArthur, & Leibovitz, 2016; Garfin et al., 2014; Hansel et al., 2010; Hurley, Saini, Warren, & Carberry, 2013; Layne et al., 2008; McConnico, Boynton-Jarrett, Bailey, & Nandi, 2016; Perry & Daniels, 2016; Shamblin, Graham, & Bianco, 2016; Stokes & Turnbull, 2016). These programs varied in their application and evaluation of the tiers (e.g. Layne et al., 2008 evaluating only two of the three tiers) and included training and/or consultation for school staff and parents, social-emotional curriculum with all students and group-based intervention with at-risk students. Layne et al. (2008) conducted the only randomised control trial (RCT), while seven studies involved pre- and post-evaluation design, one a qualitative evaluation (Hurley et al., 2013), and one presented a post-program investigation (Cicchetti, 2017). There was clear variation in the use of validated and descriptive assessment tools, including school attendance and performance data (e.g. Dorado et al., 2016; Stokes & Turnbull, 2016), and staff and student attitudes and knowledge questionnaires (e.g. Student Attitude to School Survey; Teacher Opinion Scale). The University of California Los Angeles Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (UCLA PTSD Index) was used to assess student PTSD in four of the identified studies. Two of the three-tiered models focused on processes underlying a trauma-informed approach rather than traditional whole-school behaviour management tiers, including relationship building and attachment, emotional and behavioural regulation, and post-trauma resilience and growth (Hansel et al., 2010; Stokes & Turnbull, 2016).

Four-Tier Programs

Three studies were identified as including intervention across four tiers of a trauma-sensitive model (Ellis et al., 2013; Holmes, Levy, Smith, Pinne, & Neese, 2015; Saint Gilles, 2016). These models included community and parent engagement, emotional/behavioural intervention for students, identification of students, and referral of students to mental health services. Two of these programs (Holmes et al., 2015; Saint Gilles, 2016) also involved weekly monitoring of the model with school staff for greater fidelity; however, this was not identified as a form of intervention (e.g. follow-up with school staff). Similar to the three-tiered programs, evaluation of aspects of the four-tiered models was limited (e.g. Saint Gilles, 2016). Some variation but also similarities was observed in the design and measures used to evaluate the programs, such as use of war-related measures and the UCLA PTSD Index by Ellis et al. (2013), and measures of children’s internalising and externalising symptoms (e.g. Behaviour Assessment Scale for Children Second Edition [BASC-2] and the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment [ASEBA]) used by Holmes et al. (2015) and Saint Gilles (2016).

Discussion

This systematic review evaluated the literature on multi-levelled, trauma-sensitive interventions in schools. The review identified 13 studies implementing three or more tiers of school-based support and training for childhood trauma. Many assessed components but not complete tiered systems in response to trauma, including qualitative and teacher-report data of student outcomes, and pilot evaluations. Many additional studies were excluded from this review because of the lack of specific evaluation of screening processes with students (e.g. Cohen et al., 2009) and training programs with staff. Studies involving screening may be viewed as multi-tiered, with universal screening constituting Tier 1 and targeted intervention with at-risk students constituting Tier 2. Unfortunately, school resources to screen and the limitations of measures to identify at-risk students require further consideration (see Gonzalez, Monzon, Solis, Jaycox, & Langley, 2015; Woodbridge et al., 2015).

Studies reported positive improvements in student academic achievement and behaviour (Holmes et al., 2015; McConnico et al., 2016; Saint Gilles, 2016; Stokes & Turnbull, 2016) using qualitative methods and behaviour rating scales (e.g. ASEBA and BASC-2). Studies also indicated reduced depression and PTSD symptoms (Ellis et al., 2013; Hansel et al., 2010; Layne et al., 2008; using the Depression Self-Rating Scale [DSRS] and UCLA PTSD Index), and increased self-perceived knowledge and confidence of staff (Dorado et al., 2016; McConnico et al., 2016; Perry & Daniels, 2016; Shamblin et al., 2016), using mostly non-validated measures and qualitative methods. Research with greater use of validated and standardised assessment tools to measure staff and student outcomes is required.

However, in addition to screening processes, many studies did not assess teacher and parent outcomes (e.g. Holmes et al., 2015; Layne et al., 2008), and all excluding Cicchetti (2017) failed to examine community and external service collaborations. Studies also neglected to integrate findings within existing school-wide PBS and MTSS frameworks, as recommended in the literature (Chafouleas et al., 2016; Phifer & Hull, 2016; Plumb et al., 2016; McDermott & Cobham, 2014; Reinbergs & Fefer, 2018; Weist et al., 2018). This is likely because several of the identified studies evaluated teacher training and student outcomes within already at-risk populations, including children in out of home care, and children from refugee and war-affected backgrounds. These teachers and students are likely to operate within Tier 2 and Tier 3 intervention, rather than within traditional ‘triangle’ models. Further evaluation of Tier 1 universal ‘preventative’ intervention is warranted.

However, the strength of these studies is that they provide guidance for integration of multi-tiered trauma approaches into existing school multi-tiered frameworks. Staff training and/or consultation was mentioned by eleven studies, along with community engagement and awareness mention by four studies, training and support for parents by six articles, and student support and classroom curricula mentioned by all studies. Individual parent and student treatment, and group-based student support using the CBITS and Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT) programs were also implemented and evaluated (Hansel et al., 2010; Perry & Daniels, 2016; Shamblin et al., 2016). Other programs such as Trauma and Grief Component Therapy (TGCT) also showed promise in terms of improved trauma outcomes (Layne et al., 2008).

There were several discrepancies across the programs regarding what constituted Tier 1 compared to Tier 2 and Tier 3 intervention. Alignment of the tiers within existing evidence-based approaches may help to improve the focus and outcomes of research. For example, for some of the programs, there is difficulty determining which aspects of the intervention constituted different tiers or levels of the models (e.g. Holmes et al., 2015; Perry & Daniels, 2016) and how school culture changed to adopt the trauma-informed approach.

In terms of other weaknesses, while several of the articles reported positive impacts for students and staff, only one study was a RCT (Layne et al., 2008), with most providing pre- and post-follow-up data. The nature of these interventions, often in response to adverse events, means that RCTs may not be the most appropriate research design approach for ethical and practical reasons. Longitudinal quasi-experimental evaluations in which different tiers of the intervention are provided to staff and students should be considered. Many studies also failed to evaluate outcomes of teacher training and/or consultation, and further consideration of a multi-stakeholder perspective in implementation and evaluation of multi-tiered, trauma-sensitive approaches in schools is required. This is particularly in the light of research demonstrating teachers’ experiences of helplessness and secondary trauma in relation to childhood trauma, popularity of teacher-mediated mental health programs in schools, and the impact of training on staff responses to trauma-impacted students (Alisic, 2012; Alisic et al., 2012; Berger, Carroll, Maybery, & Harrison, 2018; Dyregrov, 2009; Dyregrov et al., 1999). It is likely that several studies were excluded from the current review because the impacts of teacher training and consultation were not evaluated.

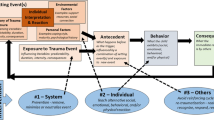

Implications

As indicated previously, one of the main limitations of research on multi-tiered models of trauma care in schools is the lack of inclusion and evaluation of school staff training within these frameworks. A meta-review found that six of the eleven post-natural disaster and conflict interventions were implemented by teachers, and therefore involved training and supervision of teachers (Fu & Underwood, 2015). Based on school-wide ‘triangle’ models and research in other areas (Simonsen et al., 2014), the following theoretical model (Fig. 2) is proposed to help guide evaluations with teachers and align teacher training within existing three-tiered models in schools. This model is also based on research regarding the training and consultation needs of staff (Dorado et al., 2016), and the differing expertise of teachers and school mental health staff (e.g. school counsellors) identified within this review (Holmes et al., 2015; McConnico et al., 2016; Perry & Daniels, 2016; Saint Gilles, 2016).

As shown in Fig. 2, three tiers are proposed for teacher intervention and evaluation, including Tier 1: universal training for all school staff regarding childhood trauma; Tier 2: consultation between teachers and school mental health staff; and Tier 3: consultation between school mental health staff and external professionals (e.g. psychologists, mental health clinicians). Tier 2 and Tier 3 acknowledge the consultative role of school mental health staff with teachers, and importance of external community and clinician engagement identified within this review (Cicchetti, 2017; Ellis et al., 2013; Hansel et al., 2010). While the benefits of teacher training have been demonstrated briefly, evaluation of the effectiveness of tiered systems of staff training on staff and student outcomes and teaching practices is required.

Limitations

Although this study aimed to only include studies that used and evaluated multiple tiers of education and support for staff, students, and/or parents regarding trauma, it became apparent during the conduct of this review that several studies included but did not evaluate some tiers of training and support. Studies of teacher training and support in particular, as well as implementation of Tier 1 positive behaviour support practices, are required. There also needs to be greater consideration of the role of parents, other school personnel (e.g. school counsellors, school leadership teams), and external professionals (e.g. psychologists and community services) in delivery and evaluation of trauma-informed approaches. The model presented in Fig. 2 informs greater inclusion of school and external mental health providers. As research continues in this area, greater use of quasi-experimental designs with an un-randomised comparison group would be appropriate, as well as evaluation of program sustainability and fidelity using longitudinal processes.

Conclusion

Overall, research on multi-tiered frameworks in response to trauma is limited but growing. Greater consistency in research methods and interventions (potentially though alignment with school-wide PBS) could improve the evidence and potentially the uptake of trauma-informed approaches in schools. The studies presented in this review provide guidance and structure for selecting, implementing, and evaluating multi-tiered, school-based trauma programs in future.

References

References marked with an asterisks indicate studies included in the systematic review

Alisic, E. (2012). Teachers’ perspectives on providing support to children after trauma: A qualitative study. School Psychology Quarterly,27(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028590.

Alisic, E., Bus, M., Dulack, W., Pennings, L., & Splinter, J. (2012). Teachers’ experiences supporting children after traumatic exposure. Journal of Traumatic Stress,25, 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20709.

Berger, E., Carroll, M., Mayberry, D., & Harrison, D. (2018). Disaster impacts on students and staff from a specialist, trauma-informed Australian school. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma,11(4), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-018-0228-6.

Berger, R., Abu-Raiya, H., & Benatov, J. (2016). Reducing primary and secondary traumatic stress symptoms among educators by training them to deliver a resiliency program (ERASE-Stress) following the Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry,86(2), 236–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000153.

Berger, R., & Gelkopf, M. (2009). School-based intervention for the treatment of tsunami-related distress in children: A quasi-randomised controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics,78, 364–371. https://doi.org/10.1159/000235976.

Bride, B. E. (2007). Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work,52(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/52.1.63.

Chafouleas, S. M., Johnson, A. H., Overstreet, S., & Santos, N. M. (2016). Towards a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health,8, 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8.

Chafouleas, S. M., Koriakin, T. A., Roundfield, K. D., & Overstreet, S. (2019). Addressing childhood trauma in school settings: A framework for evidence-based practice. School Mental Health,11, 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9256-5.

*Cicchetti, C. (2017). A school-community collaboration model to promote access to trauma-informed behavioural health supports. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,56(10S), S30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.118.

Cohen, J. A., Jaycox, L. H., Walker, D. W., Mannarino, A. P., Langley, A. K., & DuClos, J. L. (2009). Treating traumatised children after hurricane Katrina: Project Fleur-de Lis™. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review,12(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0039-2.

Day, A. G., Somers, C. L., Baroni, B. A., West, S. D., Sanders, L., & Peterson, C. D. (2015). Evaluation of a trauma-informed school intervention with girls in a residential facility school: Student perceptions of school environment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma,24(10), 1086–1105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2015.1079279.

*Dorado, J. S., Martinez, M., McArthur, L. E., & Leibovitz, T. (2016). Healthy Environments in Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS): A whole-school, multi-level, prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe and supportive schools. School Mental Health,8(1), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0.

Dyregrov, K. (2009). The important role of the school following suicide in Norway. What support do young people think that school could provide? Omega (Westerport),59(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.59.2.d.

Dyregrov, A., Bie Wikander, A. M., & Vigerust, S. (1999). Sudden death of a classmate and friend: Adolescents’ perception of support from their school. School Psychology International,20(20), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034399202003.

*Ellis, B. H., Miller, A. B., Abdi, S., Barrett, C., Blood, E. A., & Betancourt, T. S. (2013). Multi-tier mental health program for refugee youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,81(1), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029844.

Fu, C., & Underwood, C. (2015). A meta-review of school-based disaster interventions for child and adolescent survivors. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health,27(3), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2015.1117978.

*Garfin, D. R., Silver, R. C., Gil-Rivas, V., Guzmán, J., Murphy, J. M., Cova, F., et al. (2014). Children’s reactions to the 2010 Chilean Earthquake: The role of trauma exposure, family context, and school-based mental health programming. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy,6(5), 563–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036584.

Gonzalez, A., Monzon, N., Solis, D., Jaycox, L., & Langley, A. K. (2015). Trauma exposure in elementary school children: Description of screening procedures, level of exposure, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. School Mental Health,8(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9167-7.

*Hansel, T. C., Osofsky, H., Osofsky, J. D., Costa, R. N., Kronenberg, M. E., & Selby, M. L. (2010). Attention to process and clinical outcomes of implementing a rural trauma treatment program. Journal of Traumatic Stress,23(6), 708–715. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20595.

*Holmes, C., Levy, M., Smith, A., Pinne, S., & Neese, P. (2015). A model for creating a supportive trauma-informed culture for children in preschool settings. Journal of Child and Family Studies,24(6), 1650–1659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9968-6.

*Hurley, J. J., Saini, S., Warren, R. A., & Carberry, A. J. (2013). Use of the pyramid model for supporting preschool refugees. Early Child Development and Care,183(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2012.655242.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEA). (2004). Public law 108-446, 118, Stat. 2647.

Jaycox, L. H., Langley, A. K., Stein, B. D., Wong, M., Sharma, P., Scott, M., et al. (2009). Support for students exposed to trauma: A pilot study. School Mental Health,1(2), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-009-9007-8.

Kenny, M. C. (2001). Child abuse reporting: Teachers’ perceived deterrents. Child Abuse and Neglect,25, 81–92.

Kenny, M. C. (2004). Teachers’ attitudes toward and knowledge of child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect,28, 1311–1319.

*Layne, C. M., Saltzman, W. R., Poppleton, L., Burlingame, G. M., Pasalić, A., Duraković, E., et al. (2008). Effectiveness of a school-based group psychotherapy program for war-exposed adolescents: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,47(9), 1048–1062. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eecae.

*McConnico, N., Boynton-Jarrett, R., Bailey, C., & Nandi, M. (2016). A framework for trauma-sensitive schools: Infusing trauma-informed practices into early childhood education systems. Zero to Three,36(5), 36–44.

McDermott, B. M., & Cobham, V. E. (2014). A stepped-care model of post-disaster child and adolescent mental health service provision. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. https://doi.org/10.3402/3jpt.v5.24294.

Mendelson, T., Tandon, S. D., O’Brennan, L., Leaf, P. J., & Ialongo, N. S. (2015). Brief report: Moving prevention into schools: The impact of a trauma-informed school-based intervention. Journal of Adolescence,43, 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.05.017.

Mrazek, P. J., & Haggerty, R. J. (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Nadeem, E., & Ringle, V. A. (2016). De-adoption of an evidence-based trauma intervention in schools: A retrospective report from an urban school district. School Mental Health,8, 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9179-y.

Papadatou, D., Metallinou, O., Hatzichristou, C., & Pavlidi, L. (2002). Supporting the bereaved child: Teacher’s perceptions and experiences in Greece. Mortality,7(3), 324–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357627021000025478.

Perfect, M. M., Turley, M. R., Carlson, J. S., Yohanna, J., & Saint Gilles, M. P. (2016). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015. School Mental Health,8, 7–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2.

*Perry, D., & Daniels, M. (2016). Implementing trauma-informed practices in the school setting: A pilot study. School Mental Health,8(1), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9182-3.

Phifer, L. W., & Hull, R. (2016). Helping students heal: Observations of trauma-informed practices in the schools. School Mental Health,8, 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9183-2.

Plumb, J. L., Bush, K. A., & Kersevich, S. E. (2016). Trauma-sensitive schools: An evidence-based approach. School Social Work Journal,40(2), 37–60.

Powell, T. M., & Bui, T. (2016). Supporting social and emotional skills after a disaster: Findings from a mixed method study. School Mental Health,8, 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9180-5.

Price, O. A., Ellis, H. B., Escudero, P. V., Huffman-Gottschling, K., Sander, M. A., & Birman, D. (2012). Implementing trauma interventions in schools: Addressing the immigrant and refugee experience. Advances in Education in Diverse Communities: Research, Policy and Praxis,9, 95–119.

Reinbergs, E. J., & Fefer, S. A. (2018). Addressing trauma in schools: Multitiered service delivery options for practitioners. Psychology in the Schools,55(3), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22105.

Rolfsnes, E. S., & Idsoe, T. (2011). School-based intervention programs for PTSD symptoms: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress,24(2), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20622.

Runge, T. J., Knoster, T. P., Moerer, D., Breinich, T., & Palmiero, J. (2017). A practical protocol for situating evidence-based mental health programs and practices within school-wide positive behavioural interventions and supports. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion,10(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2017.1285708.

*Saint Gilles, M. P. (2016). A pilot study of the effects of a trauma supplement intervention on agency attitudes, classroom climate, head start teacher practices and student trauma-related symptomology. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Michigan, USA: Michigan State University.

Saltzman, W. R., Layne, C. M., Steinberg, A. M., Arslanagic, B., & Pynoos, R. S. (2003). Developing a culturally and ecologically sound intervention program for youth exposed to war and terrorism. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America,12, 319–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00099-8.

*Shamblin, S., Graham, D., & Bianco, J. A. (2016). Creating trauma-informed schools for rural Appalachia: The partnerships program for enhancing resiliency, confidence and workforce development in early childhood education. School Mental Health,8(1), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9181-4.

Simonsen, B., MacSuga-Gage, A. S., Briere, D. E., Freeman, J., Myers, D., Scott, T. M., et al. (2014). Multitiered support framework for teachers’ classroom-management practices: Overview and case study of building the triangle for teachers. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions,16(3), 179–190.

Smith Hatcher, S., Bride, B. E., Oh, H., Moultrie King, D., & Catrett, J. F. (2011). An assessment of secondary traumatic stress in juvenile justice education workers. Journal of Correctional Health Care,17(3), 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345811401509.

*Stokes, H., & Turnbull, M. (2016). Evaluation of the Berry Street Education Model: Trauma informed positive education enacted in mainstream schools. Melbourne, Victoria: University of Melbourne Graduate School of Education, Youth Research Centre.

Sugai, G., & Horner, R. R. (2006). A promising approach for expanding and sustaining school-wide positive behaviour support. School Psychology Review,35(2), 245–259.

Weems, C. F., Scott, B. G., Taylor, L. K., Cannon, M. F., Romano, D. M., & Perry, A. M. (2013). A theoretical model for continuity in anxiety and links to academic achievement in disaster-exposed school children. Development and Psychopathology,25(3), 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000138.

Weist, M. D., Eber, L., Horner, R., Speltt, J., Putman, R., Barrett, S., et al. (2018). Improving multitiered systems of support for students with “Internalising” emotional/behavioural problems. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(3), 172–184.

Wolmer, L., Hamiel, D., Barchas, J. D., Slone, M., & Laor, N. (2011a). Teacher-delivered resilience-focused intervention in schools with traumatised children following the second Lebanon War. Journal of Traumatic Stress,24(3), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20638.

Wolmer, L., Hamiel, D., & Laor, N. (2011b). Preventing children’s posttraumatic stress after disaster with teacher-based intervention: A controlled study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,50(4), 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.002.

Woodbridge, M. W., Sumi, W. C., Thornton, S. P., Fabikant, N., Rouspil, K. M., Langley, A. K., et al. (2015). Screening for trauma in early adolescence: Findings from a diverse school district. School Mental Health,8(1), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9169-5.

Zakszeski, B. N., Ventresco, N. E., & Jaffe, A. R. (2017). Promoting resilience through trauma-focused practices: A critical review of school-based implementation. School Mental Health,9(4), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9228-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berger, E. Multi-tiered Approaches to Trauma-Informed Care in Schools: A Systematic Review. School Mental Health 11, 650–664 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09326-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09326-0