Abstract

In mainstream political science literature, two main theoretical perspectives on the origins of political trust predominate: institutional theory which argues that political trust is generated from democratic institutions and cultural theory which argues that political trust is rooted in historical-cultural factors such as social trust. However, the influence of other social values, such as authoritarian orientations, has received little attention in the extant literature. This article investigates the determinants of political trust in 13 East Asian societies with a special emphasis on authoritarian orientations. The evidence from our empirical study suggests that authoritarian orientations are an independent cultural source of political trust in these societies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Political trust is one of the most important proxies of political legitimacy, indicating the degree to which a state (government or party) is supported by the people. Proper political trust facilitates the effective implementation of government policy. A too low level of political trust indicates that a current political regime or government has lost the support of the people, and as a consequence, a government will face many more obstacles and resistance during the process of policymaking and implementation. The continuous decline of political support since the 1960s in the USA and in other advanced industrial democracies (such as Germany, the UK, and France) has been viewed as a challenge to democracy [5, 17, 28, 52, 53]. However, compared with advanced industrial democracies, political support in newly democratic and nondemocratic nations seems to be even more problematic, especially if we think of the Jasmine Revolution and its aftermath in Tunisia, Egypt, and other Middle Eastern countries from 2011 onwards.

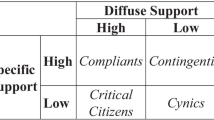

What are the origins of political trust? Several theories have been developed to explain how political trust is generated and diminishes in Western societies [17, 47, 52, 53]. Mishler and Rose find that government performance is a significant source of political trust in new post-communist democracies, while interpersonal trust as a cultural element is not [42]. Norris [47] argues that the rise of “critical citizens” in advanced societies results in the decline of political support, whereas Putnam attributes this decline to the decrease of social capital [55]. Are these explanations, based on Western or European countries, readily applicable to other regions?

Using data from the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS), we analyze political trust and its institutional and cultural origins in East Asian societies.Footnote 1 Our empirical evidence suggests that both institutional performance and cultural values affect political trust and that, from the cultural perspective, authoritarian orientations are more important than social trust. The empirical findings can improve our understanding about origins of political trust. Although existing literature has discussed the cultural origins of political trust, many papers focus on social trust (e.g., [42]) and the role of authoritarian orientations has received relatively little attention. By contrast, our paper finds that the latter is a more important cultural influence than the former. Additionally, this paper adds to the literature on the political consequences of authoritarianism. Many studies have investigated the social and political consequences of the authoritarianism of Americans [3, 29, 44, 61], but only a few have examined this topic in relation to East Asian societies where authoritarian orientations are pervasive. Shi discussed the role of hierarchical orientation on political trust in Mainland China and Taiwan but did not extend the analysis to other societies with similar historical and cultural backgrounds [59]. Another paper on the sources of political trust in East Asia also discussed authoritarianism but measured it by simply questioning whether respecting traditional authority is good or not, a measure too simplistic to reflect a respondent’s tendency accurately [70].

This paper is organized as follows. In the next part, we review two competing theories about determinants of political trust (i.e., the cultural versus the institutional). In the third section, we briefly introduce authoritarian orientations in East Asia and their changes in the modernization process as well as discussing their potential influence on political trust. The fourth and fifth sections present our research design and major empirical findings. Finally, we draw conclusions from our research and discuss its broader implications.

Explaining the Origins of Political Trust

Varying definitions of trust can be found, but as Levi and Stoker conclude, there is at least some minimal consensus about its meaning [35]. According to their definition, “trust is relational; which means it involves an individual making herself vulnerable to another individual, group, or institution that has the capacity to do her harm or to betray her,” and “trust is seldom unconditional; it is given to specific individuals or institutions over specific domains [35, p. 476].”

Our working definition of trust in this paper is “a firm belief in the reliability, truth, or ability of someone or something,” seeing trust as basically cognitive, giving rise to feelings or attitudes.Footnote 2 Accordingly, political trust refers to individual’s beliefs about the reliability, truthfulness, or capability of political organizations, institutions, regimes, and political actors. It is worth noting that trusting a particular political object, such as an organization, institution, regime, or actor, does not necessarily mean that it is trustworthy [25]. For example, the nondemocratic regime of China, which has been regarded as lacking trustworthiness because of its authoritarian (or totalitarian) attributes [16, 64, 65], has the trust of most of the Chinese population, according to recent research findings [36, 39, 67]. Therefore, we conclude that political trust refers to the perceptions or beliefs held about certain political objects rather than the actual trustworthiness of the object itself.

Following previous studies on the origins of political trust, we roughly divide the literature into two groups: one focusing on a cultural perspective and the other on an institutional one [42, 59, 70]. The cultural perspective takes social capital theory as its basis. “Cultural theories hypothesize that trust in political institutions is exogenous. Trust in political institutions is hypothesized to originate outside the political sphere in long-standing and deeply-seated beliefs about people that are rooted in cultural norms and communicated through early-life socialization [42, p. 31].” Accordingly, social trust, which can be created in people’s civil social life through their participation in civil organizations, spreads into interconnecting political activities and affects people’s trust in political institutions and actors [2, 30, 54, 62]. This cultural theory sees political trust as the projection of interpersonal trust onto political institutions and actors, which implies that higher social trust leads to higher political trust.

A different explanation is provided by institutional theory [33–35]. This argues that trust in political institutions is based on institutional performance or governance. As a result, citizens’ trust in government or other political institutions depends on the quality of governance or the performance of government and institutions. Both interpersonal trust and political trust depend on the performance of an institution rather than being a cause of good governance. This perspective holds that when political institutions are established and operated under the spirit of democracy, a government will be more efficient, transparent, and responsible. Also, citizens will have more chance to participate in political life under a democratic regime. As a result, it is easier to guarantee institutional performance. According to this theory, it is easier for a democratic regime to create social and political trust than for a nondemocratic one [24, 32, 34, 48, 64]. However, Rothstein, theorizing from an institutional perspective, disagrees with the claim that democracy, especially electoral democracy, is sufficient to create political support [57]. He emphasizes the importance of the impartiality of political institutions and the quality of government for creating political legitimacy [57]. Rothstein and others argue that trust and political legitimacy thrive mostly in societies with low levels of corruption, a well-developed social welfare system, and a high quality of public service, especially effective and fair street-level bureaucracies [23, 33, 57, 58].

Which of these two theories is most persuasive in explaining the origins of political trust? So far, research based in Western countries seems to favor institutional rather than cultural explanations and provides numerous empirical studies in support of them. Findings show that institutional performance is consistently dominant in determining political trust while cultural variables such as social trust are not consistently significant [9, 33, 42, 43, 46, 57, 66]. Studies attribute the decline of public trust in the USA and Western societies to the negative perceptions of government performances, such as declining economy, political scandals, and crimes [8, 13]. Mishler and Rose’s study of ten East and Central European countries (including Russia) also strongly supports the institutional explanation of the origins of political trust [42], but they admit in another paper that the rejection of cultural theory may be premature and suggest that cultural influences may play a more important role in the long term [43].

However, institutional theory alone is not enough to explain political trust. Cultural factors can exert significant influence as well. Moreover, political trust may be influenced not only by social trust but also by other kinds of cultural elements. In this paper, we give special emphasis to authoritarian orientations as a particular cultural element.

Authoritarian Orientations and Political Trust in East Asia

In terms of an individual authoritarian personality, Adorno et al. identified nine characteristics or symptoms such as conventionalism, authoritarian submission, authoritarian aggression, superstition, and stereotype [1]. In this paper, we suggest that the key characteristics of authoritarian orientations are deference to authority, unquestioning obedience, and reliance on authorities. Authority here can be the government, political leaders, teachers, elders, parents, or any persons with high social standing or reputation. However, political leaders or government is usually the most important authority in an authoritarian-oriented society.

The culture and history of East and Southeast Asian societies are certainly not homogenous, even within the same Confucian cultural zone.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, authoritarian orientations are widely distributed and deeply rooted in Asian societies’ culture [6, 7, 10, 11, 19, 26, 27, 38, 50, 56]. Firstly, in Confucian culture and societies, the values of loyalty (忠) (to the king or nation) and filial piety (孝) (to the parents) set up the basic norm of social behavior through both the public and private spheres [6, 38, 56, 71]. The father had absolute power to rule the entire family, and the relationship between government and people was seen as the extension of the father-son relationship. Thus, it was only natural for traditional Chinese, Korean, and Japanese societies to develop psychological and behavioral tendencies that include deference to authority, worship, and dependence. Such social psychological orientations persist in these societies, even after their political systems have changed to a democracy and their social structure has modernized [51, 71].

Additionally, authoritarian orientations are rooted deeply not only in China, Korea, and Japan but also in other Asian societies with a history of authoritarianism, such as Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines, even though these societies are relatively less influenced by the Confucian traditions. It is not difficult to find evidence that authoritarianism is still pervasive, culturally and psychologically, everywhere in Southeast Asia, influencing the exercise of power and the quality of democracy [7, 10, 11, 20, 26, 27, 29, 68]. We note too that authoritarian orientations are viewed as a factor influencing political life in some Latin American [69] and African societies [49] and even in more modernized and democratic Western countries [29].

Why are authoritarian values pervasive in this region? Although exploring sources of authoritarian orientations is not the focus of this paper, it might still be helpful to discuss briefly the roots of authoritarianism. Generally, authoritarian orientations are believed to originate from either genetic inheritance or social learning [3, 4, 41, 60]. Genetic theory seems to provide some hard evidence for the sources of authoritarianism but has been criticized for neglecting gene-environment interaction and its impact on an individual [14, 60]. Thus, social learning, which can be influenced by political and social structure, offers a more convincing explanation. For instance, almost all dictatorial (or authoritarian) regimes use propaganda through various means such as school education, political discourse, and even religion to teach people that compliance to authority and political leaders is to be taken for granted. Besides political structure, scholars also find that economic inequality is critical in shaping individual’s attitudes toward general authority through experiences with authority in the economic sphere [60]. Aside from origination, authoritarian values are continuously inherited through hierarchical, authoritarian, exploitative parent-child relationships, as well as school and other social and political relations [1, 3]. Hence, the long history of dictatorship and authoritarian rule may be responsible for the pervasive authoritarian orientations in these Asian societies.

Authoritarian orientations, as a component of culture, are not immutable though they may be stable. “Orientations vary and are not mere subjective reflections of objective conditions [21, p. 791].” The process of cultural change is similar to the evolution of biology. Generally, the gene of animals is stable, but occasionally, a genetic variant takes place to adapt to the living environment outside, especially in one encountering dramatic change in its environment. For example, Confucian culture maintained stability in Asian societies for over 2,000 years, until it encountered Western culture 150 years ago. From then on, Confucianism in each East Asian society has experienced social transformation. Two dramatic transformations occurred, modernization in the socioeconomic dimension and democratization in the political dimension, and these have determined the direction of cultural change. Authoritarian orientations, as one component of Confucianism, are fading with modernization and democratization. The hierarchical, obedient, and dependent personality attributes found in authoritarian orientations conflict with modern culture, which advocates equal and independent interpersonal relationships between people. Of course, because of cultural inertia, the extent and speed of this cultural shift depends on prior changes in the social environment, such as changes to the social structure and political system. A more recent empirical analysis also claims that “many East Asian democracies are still struggling against a haze of nostalgia for authoritarianism, as citizens compare life under democracy with either the growth-oriented authoritarianism of the recent past or with their prosperous nondemocratic neighbors [12, p. 78].” However, even though authoritarian orientations remain in these societies, their accumulation is fading, and their remaining degree is mainly dependent on the level of modernization and democratic development achieved [18].

The pervasive authoritarian values in this region can bring about significant political consequences. In this paper, we are particularly interested in how such values affect political trust. As previously mentioned, authoritarian orientations emphasize an unequal social relationship between parents and children, government and people, teacher and students, youths and elders, and boss and subordinate as well as the discouragement of any behavior intending to challenge authority. Such cultural values, inherited through family, school, and other social and political relations, will be uppermost in Asian peoples’ minds. Because government and political leaders are usually the most important symbols of authority throughout a whole country, psychological tendencies that include authority submission, worship, and dependence lead people to trust in government and political leaders without much question. Moreover, such hierarchical relationships between the government and the public lead people to regard the government as not being obligated to meet their requests. So when an unfavorable response by the government comes out, people are less likely to withdraw their support [45].

Research Design

Hypotheses

Our central hypothesis is that authoritarian orientations are a cultural origin of political trust in East Asian societies. To test the hypothesis, we performed an empirical analysis at both the macro (society) and micro (individual) levels. We were also interested in constructing an overview of changes of authoritarian orientations in the process of modernization.

In the macro-level analyses, we expected to find the following results:

-

1.

Societies with higher levels of authoritarian orientations will have higher political trust.

-

2.

Considering the impact of modernization and democratization on authoritarian orientations, those societies which are less developed and less democratic will have stronger authoritarian orientations.

To test our central hypothesis, we also performed individual-level analyses since by itself, macro-level evidence is not sufficient. The society-level correlation between authoritarian orientations and political trust can only be valid when there is a significant relationship between the two at the individual level as well. Firstly, the macro-level causal relationship works through many individuals’ decisions and behavior, and the micro-level correlation can be seen as a mechanism of such macro-level causal relationship. Political trust refers to each individual’s trust in political institutions or actors; therefore, political trust is based on individual experience, such as subjective understandings of cultural values and perceptions of institutional performances. Secondly, if the association between political trust and cultural values is significant at the aggregation level, but not significant at the individual level, it suggests that the relationship might be spurious and the analysis may be trapped by the ecological fallacy. Finally, for operationalization and methodological purposes, conducting analysis at the micro level provides a larger sample and allowed us to control several other variables, such as the demographic characteristics, omitted in small-N society-level analysis. Specifically, at the individual level, we expected to see the following:

-

3.

The stronger the individual’s authoritarian orientations, the more political trust he (or she) has.

Concept Operationalization

We constructed a comprehensive measure for authoritarian orientations by combining four variables from the ABS. The ABS asks respondents about their attitudes to the following statements: (1) government leaders are like the head of a family, and we should follow their decisions; (2) the government should decide whether certain ideas can be discussed in the society; (3) if we have political leaders who are morally upright, we can let them decide everything; and (4) children should do whatever their parents ask even if the demands are unreasonable. In order to illustrate directly and intuitively the distribution of authoritarian orientations across 13 societies in East and Southeast Asia, we calculated the mean value of the four variables for each respondent and averaged the mean values of individuals to get the mean score for each society (Eq. 1). Such a mean score represents the average strength of authoritarian orientation in that society.

where (a) value1 to value4 refer to four different measurements for authoritarian orientations in the questionnaire, (b) four-point scale for each of the four variables is converted into two-point scale: 1 means authoritarian oriented while 0 means not authoritarian oriented, (c) N is the sample size in each society, and (d) the results represent the authoritarian values in each certain society, ranging from the lowest (0) to the highest (1), and a higher value means stronger authoritarian orientations.

Using these four variables, we intended to construct a comprehensive measure for authoritarian orientations, which combines political and family authoritarian values. However, such a measure faces an inevitable trade-off between conceptual richness and empirical difficulties. On the one hand, dropping either the political or family component renders the measure incomplete since authoritarian orientations can be reflected in both family life and political domain. On the other hand, incorporating political authoritarian values into the measure brings a methodological challenge: the chosen three variables (1–3) which measure submission to the government and political leaders are closely related to political trust and thus may lead to the problem of tautology.

However, submission to political leaders or the government is theoretically different from political trust: the former refers to people unconditionally “worshiping” political authorities, while the latter may be conditional on other factors such as institutional performance. Additionally, to our knowledge, there are few existing studies which use these variables with regard to submission to political authorities in order to measure political trust. Finally, for checking purposes, we used alternative measures of authoritarian orientations in the regression analyses. For instance, we used only the obedience to parents (4) as the measure for authoritarian orientations. Because this measure has little direct association with political trust, the relationship between them is unlikely to be affected by the potential tautology problem. Similarly, we also used the obedience to teachers, which is only available in the second wave of survey. However, the main findings remain unchanged.

In measuring political trust, we combined seven variables together, which respectively measured trust in courts, national government, political parties, parliament, civil service, the military, and local government.Footnote 4 This more comprehensive measurement can better reflect an individual’s general trust in political institutions and actors. Similarly with the construction of the measure of authoritarian orientations, we assigned equal weight to each of the seven variables and specified Eq. 2 to calculate the mean value of political trust within each society, which represents the average level of political trust in that society.

where (a) trust1 to trust7 refer to trust in the court, national government, political parties, parliament, civil service, the military, and local government, respectively; (b) four-point scale for each of seven variables is converted into two-point scale: 1 means trust while 0 means not trust; (c) N is the sample size in each society; and (d) the result represents the overall political trust of each specific society, ranging from the lowest (0) to the highest (1), and a higher value means more political trust.

Survey Data

The data used in this study is from the ABS—several waves of social survey on public political opinions conducted in Asia.Footnote 5 From this database, we merged two-wave surveys (2001–2003 and 2005–2008) conducted in East and Southeast Asia, where the authoritarian orientations are quite prevalent. Finally, we ended up with around 31,871 observations from 13 societies, including Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Mainland China, Mongolia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Malaysia.Footnote 6

The quality of social surveys in authoritarian regimes, like China and Vietnam, has often been questioned. There is a reasonable suspicion that political fear could be a significant factor undermining the credibility of measurements of political issues in China or Vietnam. However, survey data is still widely used to explore the topic of political trust in China or Vietnam, and research results from surveys are published in leading academic journals [15, 37, 40, 59].Footnote 7 Among publications of this kind, the relationship between political fear and political trust or political support has been analyzed previously [22, 59], and so, while this debate exists and certainly should be considered, there is an established consensus that surveys from authoritarian regimes can still produce rigorous results. In brief, we believe that the credibility and validity of the data we are using is guaranteed and adequate for the needs of this analysis.

It is also worth noting that though we have been careful in choosing the variables for analysis to avoid too many missing values, missing values are often inevitable, especially when dealing with survey data. In the main regression analysis, we reported estimation results using various strategies of dealing with missing data, including listwise deletion, mean substitution, and multiple imputation methods. The consistent findings based on different strategies to some extent relieved our concern about the problem of missing data.

Empirical Findings

Authoritarian Orientations in East Asian Societies

To investigate how authoritarian orientations change over time and with the modernization process, we compiled data from several sources, such as the World Bank and Freedom House. Figures 1 and 2 show the relationship between economic and democratic development and authoritarian orientations at the society level.

The comparisons between the two waves within a society and those between different societies generated different findings. Firstly, as shown in Fig. 1, the authoritarian orientations within a society did not necessarily diminish drastically over a short period of time (i.e., from waves 1 to 2). Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, and Mongolia change slightly, while in some others, such as China and the Philippines, authoritarian orientations increased. This finding suggests that authoritarian orientations as cultural norms are relatively stable in the 13 societies.

Secondly, the comparison between different societies reveals that the modernization process significantly decreases the authoritarian orientations of a society, which suggests that the values are not unchangeable. In Fig. 1, we find a significant negative association (correlation coefficient = −0.75) between economy (measured by the natural logarithm of GDP per capita, PPP) and authoritarian orientations. The trend shows that the more economically developed a society, the less authoritarian oriented it is. The less economically developed societies, like Cambodia and Mongolia, are much more authoritarian oriented than rich economies, such as Japan and Taiwan. Figure 2 detects a very similar pattern between democratic development (measured by the Freedom House seven-point rating) and authoritarian orientations. The less democratic societies, like Cambodia and Vietnam, are more authoritarian oriented than democratic societies, such as Japan and Taiwan. To sum up, authoritarian orientations as a part of traditional culture appear relatively stable in the short term and do not necessarily diminish over a short period but would decrease in the long term alongside the process of democratic and economic development.

Political Trust in East Asian Societies

Figure 3 shows the average levels of political trust in the 13 societies. Generally speaking, citizens in most of these societies hold higher political trust compared with the critical citizens in advanced industrial democracies, such as the USA [67]. Among them, Vietnam has the highest rating for political trust (over 0.9), followed by Singapore (at 0.86) and Mainland China (at 0.85).

Among the 13 societies, the two democracies, South Korea and Japan, have the lowest ratings of political trust, ranging from 0.31 to 0.33. These findings, to some extent, contradict the argument of institutional theorists that it is easier for democracies to create political support than nondemocracies from the macro perspective [32, 48, 64]. Similarly, in terms of corruption control, Japan and South Korea significantly outperform Mainland China and Mongolia [63]. If institutional performance cannot fully account for the variations of political trust in this region, what else might we take into consideration as a significant factor? We argue that the authoritarian orientations could be a significant factor that drives the high political trust in these societies.

Authoritarian Orientations and Political Trust

In exploring the relationship between authoritarian orientations and political trust, we conducted the analysis at both macro (society) and micro (individual) levels. Figure 4 summarizes the society-level evidence. The trend suggests a strong positive correlation (correlation coefficient = 0.5; p value = 0.02) between the two. Political institutions and actors in societies with stronger authoritarian orientations, such as Vietnam, Singapore, and China, get more public support than those in less authoritarian-oriented societies, such as Japan. The strong correlation implies that authoritarian orientations could be an important source of political trust in this area.

We also specified an econometric model (Eq. 3) to conduct the analysis at the individual level. Different from the previous macro-level analysis in which we assigned equal weights to each subcomponent of the comprehensive measures of political trust and authoritarian orientations, we conducted a principal component factor analysis to get comprehensive indices for political trust and authoritarian values.Footnote 8 Then, we normalized the two indices.

To compare the effects of authoritarian orientations and social trust on political trust, we normalized the social trust variable. If the coefficient of the normalized authoritarian orientations index is greater than that of the normalized social trust variable, it suggests that the former has a stronger effect on political trust than the latter. For the same purpose of comparison, we normalized and controlled for several perceived dimensions of institutional performance, such as individuals’ evaluations of the (national) economy, (local) corruption, and the working of democracy.Footnote 9 We also controlled the social structure factors (X ′), such as gender, age, education, and urban residence, which, if omitted, would make the estimate results biased, since culture could be merely a secondary phenomenon dependent on social structure factors [20, 59].Footnote 10 Finally, we controlled society dummies and wave survey dummies to rule out the influence of society specific characters, such as common political fears shared by citizens and political institutions in certain societies at certain times. The term ε i is a disturbance term.

We pooled all individual observations in 13 societies and reported the estimation results in Table 1. Column 1 deals with the missing data with listwise deletion, and observations with missing values are dropped. The regression analysis reveals a strong association between the performance variables and political trust, which supports the institutional explanation of political trust. However, good performance is not the only origin of political trust. Both authoritarian orientations and social trust are positively correlated with political trust net of other factors and thus can be regarded as cultural origins of political trust. Because the effect of authoritarian orientations is statistically significant after controlling other variables, such as evaluations of institutional performance and demographic variables, the evidence suggests that the effect of authoritarian orientations is independent from other factors and such cultural values by themselves can contribute to high political trust in this region. Moreover, the coefficient of the authoritarian orientations is nearly twice as large as that of social trust, which suggests that authoritarian orientations are a more significant cultural origin in these countries than social trust which is often discussed in studies of other regions (e.g., [42]).Footnote 11 Specifically, 1 standard deviation increase in an individual’s authoritarian orientations will increase his/her political trust by a 0.122 standard deviation while a standard deviation rise in social trust will lead to a 0.057 standard deviation rise in political trust.

Some social structure factors influence political trust as well. Generally, highly educated people and urban citizens tend to have less political trust. More importantly, because less educated individuals may be more likely to have authoritarian orientations and more likely to trust political actors and institutions blindly, controlling for education in the regression model increases our confidence that the significant association between authoritarian orientations and political trust is not totally driven by blind trust. Interestingly, we also find an inverted U-shape relationship between age and political trust with the turning point at 35 to 44 years old.Footnote 12

Regression analysis in the other three columns in Table 1 addressed the problem of missing data in different ways. Column 2 replaced missing data with mean values of variables. Column 3 used the method of multiple imputation (MI) and included all the observations in the regression. Because we included the political trust index in the imputation model, it might be inappropriate to use the imputed values of political trust in the regression model since the imputed values add little information. Thus, in column 4, we separately reported the result with only the observations which have complete data on political trust. However, the main findings are similar with those in column 1. Given such consistent pattern, we employed the listwise deletion method in the following analysis.

In Table 2, we divided the whole sample into 13 more homogeneous subsamples of societies and compared the effects of authoritarian orientation in different societies. The coefficients of authoritarian orientations are consistently positive though not statistically significant at the conventional level in Vietnam. One possibility is that both political trust and authoritarian orientations are strong in Vietnam (Fig. 4), and there is not much variation within the society. Moreover, its effect in full democracies (0.125), like Japan, is not necessarily smaller than that in authoritarian regimes (0.104).

So far, the individual-level evidence has supported the hypothesis that authoritarian orientations serve as a significant cultural origin of political trust in these societies. A typical challenge to the estimation strategy is that the relationship between the two may be spurious due to omitted variables, such as the ideology indoctrination, institutions, or propaganda. However, besides controlling for various individual traits, such as education, we controlled the society dummies or ran regressions in each specific society, which helped rule out the influence of these society-level characteristics, such as society-specific institutions and political fear. Thus, we can claim relatively safely that the significant association between the authoritarian orientations and political trust is not totally driven by these confounding factors.

Another concern might be that the significant effect of authoritarian orientations was driven by the strong correlation between authoritarian orientations and trust in just a few instances rather than overall. As a robustness check, we reported the estimation results using each subcomponent of the political trust index as the dependent variable (see Table 3). Though the magnitudes vary, the effect of authoritarian orientations is consistently significant and equal to or larger than that of social trust.

Discussion and Conclusion

Although many studies have explored the source of political trust, discussion about the effect of authoritarian orientations has been marginalized. In this paper, we explored the origins of political trust in 13 East Asian societies with a special emphasis on authoritarian orientations. Considering the long history in this region of dictatorship and authoritarian rule, which is at least partially based on public support, existing institutional theory cannot fully account for the origins of political trust. We argue that authoritarian orientations as a cultural perspective are an important source of political trust in these East Asian societies. This explanation will help people understand the historical basis of rule for dictatorships or authoritarian regimes before democratic institutions emerged and why some governments still get a fair amount of support from their people even though their performance is poor (e.g., Mongolia and Cambodia).

Our hypothesis on the relationship between authoritarian orientations and political trust is supported by empirical analysis, both at the macro and micro levels. Although social trust is also a cultural origin of political trust in this region, its effect is generally smaller than that of authoritarian orientations. Moreover, the performance of institutions or actors is correlated with political trust, so promoting the development of the economy and democracy, as well as controlling corruption, earns public support for the political institutions and actors.

Though our empirical evidence shows a strong association between authoritarian orientations and political trust, it does not lead to the conclusion that governments in the 13 societies, whether democratic or authoritarian, can depend on this cultural basis indefinitely to maintain their rule. Nor does it mean that in a democratic and modernized social context, it is still a valid and desirable way to create and increase political trust. At present in China, a high rate of economic growth from an institutional perspective and authoritarian orientations from a cultural perspective provides support for the ruling parties. However, as our analysis suggests, authoritarian orientations are fading with the process of modernization of a society. The more a society is developed economically and democratically, the lower is the authoritarian orientation level. Consequently, the political effect of authoritarian orientations at the macro level may decrease with the growth of critical citizens during the modernization process. Citizens’ political trust is more likely to depend on the performance of government and institutional arrangements. Thus, in order to create the new sources of legitimacy for their rule, authoritarian governments usually tend to devote themselves to reforming the political institutions, promoting quality of governance, and seeking to control rampant corruption. However, whether these reforms and policies can lead to a greater legitimacy for authoritarian regimes remains to be seen.

Notes

In this paper, all East and Southeast Asian countries or administrative regions are called East Asian societies for the sake of convenience.

The definition is from Oxford Dictionaries, available at http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/.

The Confucian cultural zone generally refers to societies that have been culturally influenced by the philosophy of Confucius, specifically Greater China, Korea, Japan, Singapore, and Vietnam.

The survey conducted in Hong Kong does not include information on trust in the police. Thus, for the cross-society comparison purpose, we do not include trust in the police in the measurement for political trust.

For more detailed information on this data set, please see http://www.asianbarometer.org.

The original data set contains 32,015 observations. We only keep the observations which have no missing data with regard to the respondent’s gender, age, urban residence, and country, making 144 (0.4 %) observations dropped.

The information for the quality of data is also available at the site www.asianbarometer.org.

We performed the principal component factor analysis to generate the indices of political trust and authoritarian orientations. The seven measures of political trust are strongly correlated; the correlation coefficients range from 0.40 to 0.75, with the mean at 0.51. Moreover, the single factor generated via a principal component analysis accounts for 58 % of total variance of seven measures, all of which have loadings larger than 0.67 on this dimension. Similarly, the correlation coefficients between each two of the four measures of authoritarian orientations range from 0.1 to 0.38, with the mean at 0.22. The principal component analysis of the four measures of authoritarian orientations generate a single factor, which accounts for 43 % of the total variance, and the loading on each measure ranges from 0.38 to 0.75 and is 0.63 on average.

We chose corruption in local government rather than national government because there are many more missing values in the latter variable. This may be due to a lack of knowledge of corruption at higher-level governmental institutions.

To make the measures consistent across two survey waves, the continuous age was converted to 12 age groups, which were still treated as a continuous variable for simplicity, and the continuous schooling years were converted to ordinal educational degrees.

In another separate test not reported here, we deleted Hong Kong from the full sample, given that Hong Kong is a heterogeneous unit here; the national government refers to the central government of China (People’s Republic of China), while the military refers to the Liberation Army. Though a part of People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong has considerable autonomy and its citizens may not have so many interactions with the central government as in other countries. The main findings still held.

Age refers to the age group variable here. The turning point of the age group is 5 or 6 (−[−0.021 / (2 × 0.002)]), which refers to the age interval from 35 to 44.

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: Harper.

Almond, G., & Verba, S. (1963). Civic Culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Altemeyer, B. (1988). Enemies of freedom: Understanding right-wing authoritarianism. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Anderson, C. J., & Lotempio, A. J. (2002). Winning, losing and political trust in America. British Journal of Political Science, 32(2), 335–351.

Benedict, R. (2007). The chrysanthemum and the sword. Beijing: The Commercial Press.

Boudreau, V. (2009). Elections, repression and authoritarian survival in post-transition Indonesia and the Philippines. Pacific Review, 22(2), 233–253.

Bowler, S., & Karp, J. A. (2004). Politicians, scandals, and trust in government. Political Behavior, 26(3), 271–287.

Braithwaite, V. A., & Levi, M. (1998). Trust and governance. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Case, W. (2009). Contemporary authoritarianism in Southeast Asia: Structures, institutions and agency. Routledge.

Case, W. (2009). Low-quality democracy and varied authoritarianism: Elites and regimes in Southeast Asia today. Pacific Review 22, 3: 255–269.

Chang, Y. T., Chu, Y. H., & Park, C. M. (2007). Authoritarian nostalgia in Asia. Journal of Democracy, 18(3), 66–80.

Chanley, V. A., Rudolph, T. J., & Rahn, W. M. (2000). The origins and consequences of public trust in government: A time series analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64(3), 239–256.

Charney, E. (2008). Genes and ideologies. Perspectives on Politics, 6(2), 299–319.

Chu, Y. H., Diamond, L., Nathan, A., & Chull, D. (2008). How East Asians view democracy. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dahl, R. (1998). On democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dalton, R. J. (2004). Democratic challenges, democratic choices: The erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford University Press.

Dalton, R. J., & Ong, N. T. (2005). Authority orientations and democratic attitudes: A test of the ‘Asian Values’ hypothesis. Japanese Journal of Political Science, 6(2), 211–231.

Davidson, J. S. (2009). Dilemmas of democratic consolidation in Indonesia. Pacific Review, 22(3), 293–310.

Dickson, B. (1992). What explains Chinese political behavior? The debate over structure and culture. Comparative Politics, 25(1), 103–118.

Eckstein, H. (1988). A culturalist theory of political change. The American Political Science Review, 82(3), 789–804.

Geddes, B., & Zaller, J. 1989. Sources of popular for authoritarian regimes. American Journal of Political Science, 33(2), 319–347.

Gibson, J. (1989). Understandings of justice: Institutional legitimacy, procedural justice, and political tolerance. Law & Society Review, 23(3), 469–496.

Hardin, R. (1993). The street level epistemology of trust. Politics & Society, 21(4), 505–529.

Hardin, R. (2006). Trust. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Heryanto, A., & Hadiz, V. R. (2005). Post-authoritarian Indonesia: A comparative Southeast Asian perspective. Critical Asian Studies, 37(2), 251–275.

Heryanto, A., &Mandal, S. K. (2003). Challenging authoritarianism in Southeast Asia: Comparing Indonesia and Malaysia. New York: Routledge.

Hetherington, M. J. 1998. “The Political Relevance of Political Trust.” The American Political Science Review 92, 4: 791–808.

Hetherington, M. J., & Weiler, J. D. (2009). Authoritarianism and polarization in American politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kekic, L. (2007). “The Economist intelligence unit’s index of democracy.” The Economist. http://graphics.eiu.com/PDF/Democracy%20Index%202008.pdf. Accessed 12 December 2011.

Kumlin, S. (2004). The personal and the political: How personal welfare state experiences affect political trust and ideology. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kumlin, S., &Rothstein, B. (2005). Making and breaking social capital. Comparative Political Studies, 38(4), 339–365.

Levi, M. (1998). A State of Trust. In V. Braithwaite & M. Levi (Ed.), Trust and governance (pp. 77–101). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Levi, M., & Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 475–507.

Li, L. J. (2004). Political trust in rural China. Modern China, 30(2), 228–258.

Li, L. J. (2008). Political trust and petitioning in the Chinese countryside. Comparative Politics, 40(2), 209–226.

Lin, Y. T. (2010). My country and my people. Oxford: Benediction Classics

Ma, D. Y. (2007). Institutional and cultural factors of political trust in eight Asian societies: A comparative analysis. Comparative Economic and Social Systems, 5, 79–86. (Chinese)

Manion, M. (2006). Democracy, community, trust: The impact of elections in rural China. Comparative Political Studies, 39(3), 301–324.

McCourt, K., Bouchard, T. J., Lykken, D. T., Tellegen, A., & Keyes, M. (1999). Authoritarianism revisited: genetic and environmental influences examined in twins reared apart and together. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(5), 985–1014.

Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2001). What are the origins of political trust? Testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies. Comparative Political Studies, 34(1), 30–62.

Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2005). What are the political consequences of trust? Comparative Political Studies, 38(9), 1050–1078.

Mockabee, S. (2007). A question of authority: Religion and cultural conflict in the 2004 election. Political Behavior, 29(2), 221–48.

Nathan, A. J., & Chen, T. H. (2004). Traditional social values, democratic values, and political participation. Asian Barometer Survey Working Paper Series, 23.

Newton, K. 2001. Trust, social capital, civil society, and democracy. International Political Science Review, 22(2), 201–214.

Norris, P. (1999). Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government. New York: Oxford University Press.

Offe, C. (1999). How can we trust our fellow citizens? In M. Warren (Ed.), Democracy and Trust (pp. 42–87). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Paluck, E. L., & Green, D. P. (2009). “Deference, dissent, and dispute resolution: An experimental intervention using mass media to change norms and behavior in Rwanda.” American Political Science Review, 103(4), 622–644.

Park, C. M. (1991). Authoritarian rule in South Korea: Political support and governmental performance. Asian Survey, 31(8), 743–761.

Park, C. M., & Shin, D. C. (2006). Do Asian values deter popular support for democracy in South Korea? Asian Survey, 46(3), 341–361.

Pharr, S. J., & Putnam, R. D. (2000). Disaffected democracies: What’s troubling the trilateral countries? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Pharr, S. J., Putnam, R. D., & Dalton, R. J. (2000). A quarter century of declining confidence. Journal of Democracy, 11(2), 5–25.

Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Pye, L. W., & Pye, M. W. (1985). Asian power and politics: The cultural dimensions of authority. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rothstein, B. (2009). Creating political legitimacy: Electoral democracy versus quality of government. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(3), 311–330.

Rothstein, B., & Stolle, D. (2008). The state and social capital: An institutional theory of generalized trust. Comparative Politics, 40(4), 441–459.

Shi, T. J. (2001). Cultural values and political trust: A comparison of the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan. Comparative Politics, 33(4), 401–419.

Solt, F. (2012). The social origins of authoritarianism. Political Research Quarterly, 65(4), 703–713.

Stenner, K. (2005). The authoritarian dynamic. New York: Cambridge University Press.

de Tocqueville, A. (2000). Democracy in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Transparency International. (2005–2008). Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). http://www.transparency.org/. Accessed 7 June 2012.

Uslaner, E. M. (1999). Democracy and social capital. In M. Warren (Ed.), Democracy and Trust (pp. 121–150). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Uslaner, E. M. (2001). The moral foundation of trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Uslaner, E. M., & Badescu, G. (2004). Honesty, trust, and legal norms in the transition to democracy: Why Bo Rothstein is better able to explain Sweden than Romania. In Bo Rothstein, B., Rose-Ackerman, S., & Kornai, J. (Ed.), Creating Social Trust in Post-Socialist Transition (pp. 31–51). New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Wang, Z. X. (2005). Before the emergence of critical citizens: Economic development and political trust in China. International Review of Sociology, 15(1), 155–171.

Wang, Z. X. & Tan, E. S. (2012). The conundrum of authoritarian resiliency: Hybrid regimes and non-democratic regimes in East Asia. Asian Barometer Working Paper Series, 65.

Wiarda, H. J. (2002). The soul of Latin America: The cultural and political tradition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Wong, T. K. Y., Wan, P. S., & Hsiao, H. H. M. (2011). The bases of political trust in six Asian societies: Institutional and cultural explanations compared. International Political Science Review, 32(3), 263–281.

Yang, K. S. (1995). “Chinese social orientation: An integrative analysis.” In Lin, T. Y., Tseng, W. S. & Yeh, Y. K. (Ed.) Chinese Societies and Mental Health (pp. 19–39). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and reviewers for their helpful suggestions. Financial support came from the Humanities and Social Science Programme 2013 of Ministry of Education, China (project number: 13JYA630063) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (project number: NKZXA1211). We also appreciate the Asian Barometer Project Office (www.asianbarometer.org) for providing data collected by the Asian Barometer Project, which was co-directed by Professors Fu Hu and Yun-han Chu and received major funding support from Taiwan’s Ministry of Education, Academia Sinica and National Taiwan University. The Asian Barometer Project Office is solely responsible for the data distribution. The views expressed herein are the authors' own and we alone are responsible for any remaining errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, D., Yang, F. Authoritarian Orientations and Political Trust in East Asian Societies. East Asia 31, 323–341 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-014-9217-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-014-9217-z