Abstract

Confronted with structural demographic challenges, during the last decade European countries have adopted new labour migration policies. The sustainability of these policies largely depends on the intentions of migrants to stay in their country of destination for the long term or even permanently. Despite a growing dependence on skilled labour migrants, very little information exists about the dynamics of this new wave of migration and existing research findings with their focus on earlier migrant generations are hardly applicable today. The article comparatively tests major theoretical approaches accounting for permanent settlement intentions of Germany’s most recent labour migrants from non-European countries on the basis of a new administrative dataset. Although the recent wave of labour migrants is on average a privileged group with regard to their human capital, fundamentally different mechanisms are shaping their future migration intentions. In contrast to neo-classical expectations, a first path highlights economic factors that determine temporary stays of a creative class benefiting from opportunities of an increasingly international labour market. Instead, socio-cultural and institutional factors are the decisive determinants of a second path leading towards permanent settlement intentions. Three main factors—language skills, the family context and the legal framework—make migrants stay in Germany, providing important implications for adjusting and strengthening labour migration policies in Europe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The demographic structure of Europe is in a process of fundamental change. Increasing life expectancy and declining fertility confronts most European countries with the prospect of a shrinking as well as ageing labour force population. Although many of these processes are currently blurred by the sweeping influences of the economic and financial crises, the consequences of the demographic distortions will be felt even more dramatically once national economies begin recovering (cf. OECD 2010). In face of these changes, the European Union (EU) already started to propagate new migration policies in its Lisbon Agenda of 2000. Germany followed this wake-up call and is today one of the most prominent examples in Europe of a nation transforming its previously restrictive labour migration policies towards an active recruitment of international talent from non-European countries. From 2000 onwards, it started to adapt its policies to evolving demographic and economic demands and in 2005 a new Immigration Act altered the legal framework structuring Germany’s immigration and integration regime. In the following years, additional reforms ensued, resulting in an overall liberal policy targeting skilled and highly skilled workers. Despite the recent upswing of immigration to Germany, the sustainability of these new policies largely depends on the intentions of migrants to stay in their new country of destination permanently or at least for the long term. Policymakers are particularly keen to gain a more thorough understanding of why these new labour migrants would want to settle. Whereas traditional immigration countries have conducted new immigrant surveys in response to these issues (e.g. Jasso et al. 2000), hardly any comparable development is found in Europe where very little information exists about the dynamics of this new wave of labour migration from non-European countries.

The traditional perspective on settlement trajectories of labour migrants originates from the consequences of the global recession in the 1970s when many of the immigrant-receiving countries of Europe and North America experienced the return migration of their guest workers. Matched by a political imperative of reducing the size of the foreign population, researchers studied the intentions and decisions of migrants to return (e.g. King 2000). Today, the new demographic and economic challenges reversed this perspective with policymakers and scholars now focusing on the determinants prompting migrants to stay permanently in the country of destination (Diehl and Preisendörfer 2007; Khoo 2003; Massey and Redstone Akresh 2006). Existing findings about settlement trajectories thus originate from the experiences of earlier generations of immigrants. Different theoretical approaches have been tested focusing on economic, socio-cultural as well as political factors, all demonstrating that settlement processes show great differences regarding the overall probability of return as well as selectivity between different groups. Although the migration dynamics of the guest worker era are well understood, these findings are of little practical relevance for Europe’s most recent labour migration experiences. There are fundamental differences between earlier and current immigrant generations with respect to the political and economic context, their socio-economic characteristics as well as their early integration experiences.

Addressing this situation, the article provides a first analysis about the settlement intentions of Germany’s most recent labour migrants. With an existing European free movement regime, migration policy concentrates on the regulation of third country nationals from outside the EU. In line with this institutional framework, the article addresses the major driving forces affecting the intentions of recently arriving new immigrants from non-EU countries to permanently stay in Germany compared to the intention to return to their country of origin or leaving for an alternative country. Earlier studies already “caution against an over-reliance on single theories in understanding and explaining” these migration dynamics (cf. Constant and Massey 2002, p. 7) and the article aims to comparatively test major opposing theoretical approaches. Data about the actual settlement process of migrants is only available long after potential return migration has ended. Therefore, the study follows a general trend in this research tradition and focuses on migrants’ intentions as a strong determinant of actual behaviour. Although migrants potentially adhere to a “myth of return” and original intentions might not always result in actual behaviour (cf. Anwar 1979; Kalter 1997; Pagenstecher 1996), they have profound consequences for early integration processes and subsequent migration decisions.

In the next section, the article starts with a presentation of Germany’s new legal regulations governing labour migration from non-European countries before the three major theoretical approaches on return migration and subjacent settlement intentions are discussed. Section “Data and Operationalisation of Theoretical Constructs” introduces the surveys on foreign workers conducted by the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, constituting the most extensive source of information about the recent wave of labour migrants in Europe today. Section “Determinants of Permanent Settlement Intentions” discusses the empirical measurement of the theoretical constructs on the basis of this dataset before the following two sections present the findings. The analyses show that on average the recent wave of labour migrants from non-European countries is a very privileged group with regard to their human capital, economic as well as social integration. Different paths are separated leading to permanent settlement intentions, showing a profound dualism between a creative class freely pursuing the economic opportunities of the international labour market for limited periods of their life compared to more traditional images of migration where the relocation of the centre of their life serves as a long-term investment in better living conditions.

Germany’s New Labour Migration Regime

Although Germany was traditionally characterised as a “reluctant country of immigration” (Cornelius et al. 1994), it has already experienced at least three waves of large-scale labour migration. The first wave started during the economic recovery after World War II. From 1955 onwards, Germany institutionalised its guest worker policy and allowed the active recruitment of foreign labour based on bilateral agreements with the sending states (cf. Salt and Clout 1976; Schönwälder 2001). This period ended with the recruitment stop in 1973, which was followed by a policy stressing the priority of the national work force that reduced labour migration to a minimal level. This situation did not change until the late 1980s, when the lack of employees in certain economic sectors resulted in the introduction of new labour migration schemes that launched a second wave of large-scale labour migration. Again, a system of bilateral government agreements for the temporary admission of workers from Central and Eastern European countries was set up, which provided employment opportunities for contract work, seasonal and posted workers as well as cross-border commuters (cf. Faist et al. 1999).

The most recent wave of labour migration from non-European countries was set in motion shortly after the turn of the millennium, when Germany—alongside the adoption of the European Lisbon Agenda—started to reform its labour migration policy. In a first step, the introduction of the so-called Green Card gave up to 20,000 highly skilled information technology specialists comparatively non-bureaucratic access to the German labour market. This opened the discussion of a broader reform of Germany’s labour migration regime, which resulted in the 2005 Immigration Act introducing three major labour migration titles providing a new legal framework for this policy area:

-

(1)

General labour migration (Section 18 of the Residence Act): The new title stipulates that third country nationals may be granted a temporary residence permit for the purpose of taking up employment under specific requirements. Although the title principally covers different forms of labour migration, it focuses in particular on skilled migrants.

-

(2)

Highly skilled labour migration (Section 19 of the Residence Act): Highly skilled migrants obtain a permanent settlement permit immediately upon arrival. Their family members are also entitled to take up paid employment. The regulation covers in particular scientists as well as executive personnel receiving a salary corresponding to at least one and a half of the earnings ceiling of the statutory health insurance scheme (in 2005 this corresponded to 84,600 euros).

-

(3)

Self-employed migrants (Section 21 of the Residence Act): For the first time, regulations on self-employed migrants were included. Their planned business project generally required an investment sum of one million euros, the necessity to create at least ten new jobs and the assessment of the underlying business plan by the local chamber of industry and trade. Those migrants successfully realising their planned economic activity are provided permanent residency after 3 years (for a more detailed overview about these developments, see Ette et al. 2012).Footnote 1

During the following years, the requirements for all three titles were successively reduced, additionally increasing the rights for skilled and highly skilled labour migrants. One aspect concerns Section 18 where the Labour Migration Control Act from 2009 as well as several smaller reforms principally broadened the group of potential beneficiaries permitted to apply for temporary labour migration. With respect to Section 19, the reform in 2009 also substantially reduced the salary level from 84,600 euros to 63,600 euros. Finally, the self-employed labour migration scheme witnessed three reforms taking place within the 2007 Transposition Act (minimal investment sum reduced to 500,000 euros, required number of new created jobs reduced to five), the 2009 Labour Migration Control Act (minimal investment sum reduced to 250,000 euros) and the 2012 Transposition Act, which finally dropped those requirements altogether, only asking for a promising business idea.

The development of labour migration shows that next to the changing economic context and resulting diversion effects (Bertoli et al. 2013), the political reforms since 2005 have been primary causes of an obvious increase of skilled and highly skilled labour migrants in Germany. While the number of 18,000 labour migrants from third countries in 2005 was relatively low, in 2012 it increased to 39,000 immigrating on the basis of the three new migration titles. While family reunification previously constituted the single most important group of migrants from non-European countries next to foreign students (excluding humanitarian migration), in 2012 the share of employment-related residence titles issued for the first time almost surpassed family migrants. This trend of increasing labour migration is likely to continue due to additional policy reforms introducing further labour migration titles (e.g. the recent introduction of the European Blue Card) as well as changes to the Employment Regulation increasing access to the German labour market for all skilled labour migrants during the summer of 2013.

Theorising Settlement Intentions of International Migrants

Settlement intentions do not develop randomly but are generally highly selective with respect to the individual characteristics of international migrants. The decision to leave a country of origin is usually based on particular aspirations and motivations that are intimately linked to an intended duration of staying abroad. This conglomerate of objectives already exists before actual migration but will quickly be re-evaluated on the basis of the actual circumstances encountered by migrants in the country of destination. From a theoretical perspective, the existing literature differentiates at least three approaches. They focus either on economic, socio-cultural or institutional determinants of individual intentions and trajectories of settlement.

In its most basic form, neo-classical economic theory explains migration as an attempt by individuals to maximise expected returns either in the form of higher incomes or alternatively by other standards of economic success (cf. Massey et al. 1998; Sjaastad 1962). Applied to the case of settlement intentions, migrants who are more productive in the region of destination than in their countries of origin are expected to opt for long-term or even permanent settlement. A high incidence of unplanned short-term migration and interest in returning home exists only in cases in which migrants either made their original migration decision based on a faulty calculation of potential costs and benefits or failed to integrate economically in the country of destination (Borjas and Bratsberg 1996). The first hypothesis (H1a) consequently anticipates a positive relationship between the economic success of new immigrants and their intended duration of stay in the country of destination. Empirical evidence for this hypothesis is largely inconsistent. During recent years in particular, studies regularly documented contradictory findings showing negative effects of labour market involvement on settlement intentions or actual return migration (e.g. Bijwaard and Wahba 2013; Dustmann and Weiss 2007). For migrants of very high economic status, international migration hardly pursues directly measurable economic returns but follows the logic of an increasingly global labour market and the staffing practices of multinational companies (Pohlmann 2009). According to Massey and Redstone Akresh (2006, p. 969), the bearers of skills, education and abilities are increasingly likely to maximise their earnings in the short term without any long-term links to the country of destination. In line with this reasoning, the second hypothesis (H1b) states that the intended durations of stay decrease with increasing economic success.

The second approach emphasises the existing socio-cultural integration of migrants in their countries of destination. Generally, the approach argues that building up social and cultural ties are investments in the host society that are hardly transferable to a different context. The literature highlights rather diverse types of ties including ethnically diverse networks (Waldinger 1994), second language learning (Esser 2006), the integration of partner and children in the host society (Dustmann 2003), political activities in the host society (Tillie 2004), as well as more cognitive and attitudinal changes of migrants adapting to dominant norms of the country of destination. From this perspective, a third hypothesis (H2a) anticipates that successful socio-cultural integration of new immigrants in the country of destination has a positive effect on the intended durations of stay. In the context of the “new economics of migration”, the key insight of which was its focus on the family and the household as the main locus of migration decisions, it may be rational to invest in the host society without having long-term settlement intentions. With some household members working in the local labour market, others are earning a living in foreign labour markets to provide a reliable stream of remittances supporting those who remain at home. In this context, migration is seen as a livelihood strategy minimising economic risks (cf. Stark and Bloom 1985; Taylor 1999). Optimising their integration in the country of destination positively influences their ability to support the household in the country of origin. Nevertheless, this has no effect on settlement intentions because the principal focus of this migration project remains the family or the household in the country of origin, and as soon as the need to stay abroad decreases, the migrant will most likely return (Constant and Massey 2002). Whereas this theoretical mechanism emerged from the situation in the developing world, a more mundane argument would also anticipate a negative relationship for all those cases in which the spouse or family decided to permanently stay in the country of origin. Due to their desire to reunite after a temporary stay abroad, this will sustain the migrants’ attachment to the country of origin. Consequently, the fourth hypothesis (H2b) anticipates a negative effect of family ties in the country of origin on the intended durations of stay.

Whereas these first two approaches concentrate on the individual actor and his or her household context, a third approach highlights the institutional context framing the settlement intentions of migrants. During the last two decades, transnational migration theories in particular (cf. Faist 2000; Levitt and Jawosky 2007) called for the incorporation of the social, economic, cultural and political environments at both ends of the migration process—the country of origin as well as destination—in explanatory models. The empirical application of theories addressing the meso-level of migration is regularly hampered by the unavailability of data. Ideally, we would include indicators of the local conditions in countries of origin and destination as well as information about economic, social, cultural and political ties maintained in this border-crossing space. Adequately addressing those institutional contexts is also beyond the scope of this article but two crucial aspects have to be taken into account: the first aspect addresses the crucial influence of the context of departure (particularly the political, economic and social environment) on the motivations for migration and the intended duration of the stay abroad. The fifth hypothesis (H3a) consequently argues that the stronger the desire to move abroad the greater the positive effect on the intended duration of stay. The second aspect relates to the context of arrival and the institutional and legal conditions. The “warmth of welcome” (Reitz 1998) is an important determinant for the integration of immigrants and migration studies regularly document the positive impact of more favourable opportunity structures on the fortune of migrants. Applied to settlement intentions of migrants, previous research on earlier waves of labour migration in Europe as well as on more recent contexts showed a reverse relation between rights and opportunities granted to immigrants and their intended duration of stay. The easier mobility is for migrants, the larger the migrants’ feeling that they can return to the country of destination, even after long periods of absence (see, e.g. Akwasi 2011; Carling 2004). In line with this reasoning, a final hypothesis (H3b) argues that the provision of more rights and opportunities to immigrants negatively effects the intended duration of stay. All three approaches were developed in the context of previous waves of international migration. In the following sections, the opposing hypotheses will be put to a test to better understand the settlement intentions of the most recent wave of labour migrants in Germany.

Data and Operationalisation of Theoretical Constructs

Migration scholars regularly struggle to analyse the recent dynamics of international migration because most surveys sampling the immigrant population are dominated by former generations of migrants, generally resulting in very small numbers of recent newcomers. In Germany, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) recently carried out three surveys of migrants who were granted one of the three residence permits providing for the immigration of general (Section 18), highly skilled (Section 19) and self-employed (Section 21) labour migrants from third countries outside the European Union. The sampling of these surveys was based on the Central Register of Foreigners. The three paper and pencil surveys were conducted between 2008 and 2011, and the resulting harmonised dataset today provides the most comprehensive source for analysing the most recent wave of labour migration from third country nationals to Germany.

Overall, 4,702 interviews were carried out across all three surveys with 3,248 interviews originating from the group of migrants holding a residence permit for general labour migrants (Section 18), 510 interviews with highly-skilled newcomers (Section 19) and 944 interviews with self-employed persons (Section 21).Footnote 2 For the empirical analyses, the original sample was restricted to the most recent labour migrants who immigrated to Germany during the last 5 years before the interview reducing the sample by 36 %.Footnote 3 Additionally, 641 interviews were excluded from the analyses because of missing or implausible information resulting in 2,352 interviews.

The dataset provides different co-variables to test the hypotheses, although the original purpose of the individual surveys together with necessary post-hoc harmonisation clearly restrict the abundance of potential constructs. The settlement intentions of recent labour migrants constitute the dependent variable. During the surveys, all respondents were asked how long they intend to stay in Germany with four answer categories provided: (1) less than 5 years, (2) between 5 and 10 years, (3) more than 10 years and (4) permanently. Whereas the first two categories provide relatively concrete time horizons characterising temporary migration, the latter two answers are certainly selected only by respondents who already have a long-term or even permanent settlement intention. Whereas 35 % indicate a short-term stay and another 25 % plan temporary migration for up to 10 years, the descriptive statistics in Table 1 shows that with 40 %, a relatively large number of recent labour migrants intend permanent stays in Germany (23 % indicate stays for more than 10 years and 17 % permanently). From a political perspective, this finding is important because it signifies a principal attachment of many newcomers to Germany. From a methodological perspective, however, it is important to keep in mind that this high proportion is likely to be an overestimate because migrants with temporary migration intentions might have already left Germany. Nevertheless, with the focus of the paper on the selectivity of migrants and their differential chances for permanent settlement rather than the absolute rate, this overestimate does not affect the findings.

All subsequent analyses control for major demographic factors likely effecting settlement intentions—gender, age, (age2) and date of immigration. With respect to those characteristics, Germany’s recent labour migrants closely resemble previous waves of labour immigration including an obvious gender bias with more than two third of all respondents being male migrants and a generally young population with a mean age of 33.8 years (cf. Table 1). Additionally, the literature regularly points to the positive relationship between duration of stay in the country of destination and the chances for permanent settlement intentions (e.g. Waldorf 1995, p. 128). The multivariate models consequently control for this effect by including the years since immigration, which varies between 0 and 5 years. The most recent migrants slightly dominate this sample with 49.2 % who moved to Germany during the last 24 months, an effect which is most likely caused by the recent increase of labour migrants and potential return migration of earlier labour migrants.

To test the explanatory power of hypotheses H1a and H1b, which stress the importance of economic integration as the crucial determinant accounting for settlement intentions, a first variable measures educational achievements. Germany’s recent focus on skilled and highly skilled labour migrants results in 87 % of respondents in the sample holding a university degree. Compared to the demographic characteristics, this is a first indicator demonstrating obvious divergences between the previous compared to the most recent wave of labour migration. A second aspect of economic integration is represented by income measured as yearly gross income with three broad levels of yearly income: below 25,000 euros (31 %), between 25,000 and 55,000 euros (43 %), and migrants with a yearly salary above 55,000 euros (26 %). More recently, scholars problematise the objective measurement of economic success because new immigrants in particular evaluate their individual economic satisfaction in reference to their perceived status in the country of origin. Not the absolute income is thus the crucial indicator, but the difference between the context of departure and arrival. Combining two items (satisfaction with the current job as well as satisfaction with the income) to a new economic satisfaction index ranging from not satisfied (coded 1) to very satisfied (coded 5) includes the migrants’ subjective assessment of their economic satisfaction as a third variable—a mean of 3.81 documents that new labour migrants in Germany are generally pleased with their economic situation.Footnote 4

A second group of co-variables operationalises theoretical approaches, emphasising the socio-cultural integration of migrants as an important predictor of their settlement intentions. The rather complex theoretical construct is regularly disaggregated into simpler indicators with language skills of the destination country constituting one of the most regularly applied constructs (e.g. Diehl and Preisendörfer 2007; Esser 2006). For the empirical analyses, a categorical variable was constructed comparing those with minor language abilities (30 %) with those with medium (46 %) and very good skills (24 %). The existing information about the family status is applied as a second co-variable in the latter analyses differentiating between singles (35 %), migrants whose partner lives with him or her in Germany (53 %) and those migrants with partners living abroad (11 %). Finally, a third co-variable tests for the experiences and the integration of family members in the country of destination. In the absence of detailed information about the occupational status of the partner, the subjective assessment of the opportunities of the partner on the labour market in Germany is applied as an additional co-variable to measure the living conditions of migrants in Germany. The variable differentiates between good and very good chances on the labour market compared to all other constellations.Footnote 5

Finally, the third group of co-variables tests the influence of the institutional context at both ends of the migration process in the countries of origin and destination. A first variable focuses on the country of destination and tests for the influence of the legal framework regulating migration applying the information available about the residence title. The variable differentiates between two legally distinct groups of labour migrants: the first consisting of labour migrants who immigrated on the basis of Sections 19 or 21 of the German Residence Act (21 %, highly skilled and self-employed). Both offer nearly similar sets of rights either offering them permanent residence right from the start (Section 19) or a transparent path to permanent residency under defined criteria already after 3 years of residence (Section 21). The second group has been granted temporary residence titles only (Section 18). Although these permits also allow for repeated renewal, potentially also resulting in a permanent title, the path is far less transparent and dependent on several conditions and administrative discretion.

The pre-migration context in the country of origin is operationalised on the basis of two additional co-variables. Testing the influence of individual motives and the overall desire to settle abroad, the subsequent analyses include two index variables. Respondents were confronted with a list of 11 items asking migrants about the importance of different pull factors for their original migration decision. Respondents indicated the importance of all motives on a seven-point Likert scale and a separate factor analysis reduced the different items to their unobserved latent variables resulting at a two-factor solution with a first factor including the human capital-related migration motives (HC), whereas a second factor concentrated on social capital-related factors (SC) including previous contacts, language and the family.Footnote 6 Based on these results, two additive indexes were constructed with the first covering the human capital migration motives and the second the social capital-related migration motives, both ranging from 1 to 7 with 7 indicating greatest importance of the individual motive (cf. Fig. 1).

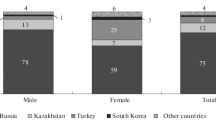

The original migration motives hardly operationalise any information about the pre-migration social and economic conditions in the migrant’s sending country. Dummy variables controlling for individual countries and regions of origin are included in the subsequent analyses operating as a proxy for individual motivations for different lengths of stay caused by the institutional context in the country of origin (cf. Massey and Redstone Akresh 2006, p. 958). Altogether eight different source countries or regions are differentiated. The fact that 29 % of the respondents come from western industrialised countries like the USA, Canada and Australia fits earlier waves of migration because they are traditionally important source countries. The small percentage of 8 % from European third countries including former Yugoslavian countries as well as Turkey however shows a clear divergence from earlier periods. Additionally, 19 % of newcomers from Russia, 16 % from China and 7 % from India mark an obvious diversification of the regions of origins.

Determinants of Permanent Settlement Intentions

The analysis of the individual motivations and determinants explaining the settlement intentions of Germany’s recent labour migrants concentrates on the opposition of temporary and permanent immigration suggesting the estimation of binary logistic regression models.Footnote 7 The results of all four models are highly significant and Table 2 presents logit coefficients, standard errors and the level of significance for each of the estimated variables. The first model estimates the effects of co-variables controlling for demographic selectivity of settlement intentions. The results confirm existing studies documenting a small and statistically insignificant difference between male and female migrants. There is an obvious influence of the age distribution with each additional year in the lifespan increasing individual chances for permanent settlement—a trend that reverses in older age groups. Similarly, the date of immigration has an important effect in estimating patterns of settlement intentions. The odds ratio for the first model shows that each additional year migrants live in Germany increases the chances of permanent migration projects by 35.1 %. This is caused by an important consolidating effect of the duration of stay but also by the selective return of temporary migrants discussed above.

Based upon this demographic framework, the following models gradually add the different groups of theoretical co-variables. The first step tests the predictive power of economic approaches with unambiguous and consistent results across all models. In line with the expectations of H1b, a negative relationship exists between human capital and the intended duration of stay with migrants holding a university degree having a 32.9 % lower chance than migrants with secondary education as highest formal education. Including yearly gross income confirms these results with higher salaries significantly reducing the intended duration of stay. Only the impact of subjective assessments of economic integration results in a positive relationship between economic satisfaction and intended durations of stay discussed in H1a. The overall pattern of these results, however, documents that the most skilled and successful migrants belong to an internationally highly mobile group of persons with little prospects to stay permanently in Germany.

In a second step, socio-cultural approaches are evaluated. In contrast to economic integration but in line with H2a, socio-cultural integration—here measured by language skills—actually increases the chances for permanent settlement intentions. From this perspective, language skills are an investment in a specific country of destination that are hardly transferable to a different context and thus positively influence the intended length of stay. With respect to the household constellation, however, empirical results did not support theoretical hypothesis H2b. According to the new economics of migration approach, having family in the country of origin would reduce long-term settlement intentions. A partner living abroad has only a weak and statistically insignificant effect. Instead, those migrants living with their families in Germany have significantly higher odds of intending long-term stays in Germany. Additional indicators provide evidence that socio-cultural living conditions are of more relevance than individual economic situations for permanent settlement intentions. In addition to language skills, good economic opportunities for the partner in Germany are also positively associated with long-term settlement intentions.

Finally, the fourth model adds indicators measuring the impact of potential institutional determinants. The results show a positive relationship between having more rights and the intended duration of stay: Labour migrants from non-European countries in Germany holding a permanent residence title have a more than two times higher chance of permanent settlement intentions because their investment in the country of destination is far less precarious. Furthermore, the two groups of motives—human capital as well as social capital motives—both display a statistically significant positive effect on the duration of stay. Finally, the country dummies show that compared to western industrialised countries, labour migrants from all other regions of origin are more likely to display a higher intention for permanent settlement. These differences between countries of origin confirm earlier studies (e.g. Khoo et al. 2008, p. 206; Haas and Fokkema 2011) and are of great practical relevance. From a theoretical perspective, however, these results are unsatisfying because even when controlling for important co-variables, theoretical effects unaccounted for by the model remain. The inclusion of those co-variables testing for institutional approaches, however, also has important effects for the other theoretical frameworks. Whereas the effects of all socio-cultural integration co-variables remain largely constant, economic integration indicators lose their explanatory power. Together these findings point to largely different theoretical mechanisms driving settlement intentions for different groups of labour migrants.

Multiple Paths Leading to Permanent Settlement

The inclusion of institutional factors modelling the context of departure and arrival fundamentally change the direction of effects found in the previous models. Particularly, the different motives of migration together with the fixed effects of regions of origin reverse statistically significant relations between settlement intentions and the economic and socio-cultural integration of recent labour migrants. Testing the hypothesis that different theoretical mechanisms are only indicative for specific contexts of departure, separate models are estimated for the two most divergent regions of origin of newcomers in Germany: western industrialised countries compared to all other third countries. The results presented in Table 3 clearly show that different paths and logics underlying individual calculations of the duration of settlement have to be taken into account in analyses of the dynamics of the most recent wave of labour migrants.

The restricted model focusing on western industrialised countries shows many similarities to hypothesis H1b, which expects settlement intentions to vary in line with the calculations of an economic elite acting as short-term maximisers of their economic opportunities. Temporary stays in Germany are often individual responses to the requirements of an increasingly global labour market with human capital-related motives driving those migrants out of their home countries while social capital motives do not play a significant role in their intention to stay permanently. In line with these results, it can be shown that higher levels of human capital and income significantly increase the chances for temporary stays abroad. The family and household context offers additional support for the economic elite hypothesis: Neither the company of the migrants’ family in Germany nor the potential integration of the partner is a decisive factor taken into account in the decisions about settlement intentions. In addition to language skills, only few factors increase the intended duration of stay in Germany, with the 30 % of all respondents who are female labour migrants having a 50 % higher chance of intending to stay permanently compared to their male counterparts.

For migrants from all other third countries, the underlying theoretical mechanisms seem almost diametrically opposed. The finding that individual economic integration is not taken into account when decisions about settlement intentions are taken is of particular importance. Although the negative effect of human capital remains, neither the objective amount of income nor satisfaction with job or income is a relevant determinant. These results largely contradict both hypotheses concerning economic driving factors. The investment in the country of destination acts as a good predictor of permanent settlement intentions and is of particular importance. This includes the investment in language skills as well as migration in the family context. Those migrants who live with their partner or family in Germany—and experience better integration opportunities for the partner—have a significantly higher chance for permanent settlement. Surprisingly, in this subgroup, the reasoning of the new economics of migration approach is also not supported, with a remaining family in the country of origin having no effect on the dependent variable. In addition to the socio-cultural integration, the institutional approaches also play a largely different role. Whereas the institutional context of reception has no effect on the intentions of migrants from western industrialised who regard them as necessary administrative structures only, labour migrants from other regions of origin see them as actual opportunity structures having a strong influence on their settlement intentions. Finally, the original migration motives also differentiate migrants from both contexts of reception because not only economic motives but also original social capital motives have a positive impact for long-term residency intentions.

From a theoretical perspective, these findings provide additional support for the more recent attention to the institutional contexts in countries of origin and destination to understand the dynamics of international migration. From a more practical perspective, the results provide interesting starting points for designing labour migration policies as a more sustainable solution for countries with ageing societies. The results show that labour migrants from western industrialised countries have a relatively low probability of staying in Germany permanently. Of average migrants from this region of origin—male, single, 35 years old, medium income and medium command of German who immigrated 2 years before—only every tenth intends to stay in Germany permanently. Only few options exist to increase the settlement intentions of this group because different indicators of economic as well as socio-economic integration have a negative impact. Migrants from all other third countries who share the same characteristics have a similar probability of permanent settlement intentions. However, in this group of migrants, the probability largely increases with respect to socio-cultural and institutional factors, which are both more easily controlled by a more favourable institutional framework. The probability doubles for same migrant who brings a partner to Germany and experiences good opportunities to integrate. Providing the very same migrant with a permanent residence title would mean almost every second migrant would intend to stay permanently in Germany.

Conclusion

Including international migration in any strategic response to the labour market implications of changing demographic structures necessarily involves the acceptance of many preconditions. This includes the acceptance of increasing cultural diversity by the host society, potential ethical consequences of tapping into other countries’ human resources as well as the principal interest of migrants to work and settle in the new country of destination. Responding to this last aspect, the paper provided an initial analysis of Germany’s most recent wave of labour migrants from non-European countries and their intentions to stay. Intentions expressed in an interview situation should not be regarded as fixed external factors determining individual future location decisions but can always change during the life course. The experience that “there is nothing more permanent than temporary foreign workers” (Martin 2001) may be updated by the current wave of migrants, but in a situation where Germany seeks out additional skilled labour forces abroad, settlement intention is the most important indicator available.

Compared to previous studies, the analysis profited from its strict focus on labour migrants from third countries. Nevertheless, we differentiated two alternative paths for labour migrants leading to permanent settlement. The first path relates to migrants from western industrialised countries whose intentions are primarily shaped by economic motives. The results, however, clearly reject traditional neo-classical expectations about a positive relationship between the economic success of new immigrants and their intended duration of stay. On the contrary, the most successful and economically integrated migrants show the lowest propensity to permanently settle in their new country of destination. Certainly not all migrants from this region of origin follow this economic pattern and very good language skills greatly increase the chances of permanent settlement intentions. The results support an image of a creative class profiting from the opportunities offered by an increasingly international labour market that provides the country of destination few toeholds to make them stay.

The second path looks rather different and relates to labour migrants originating from all other third countries. Socio-cultural factors and the institutional context are now the decisive determinants accounting for the intended duration of stay in Germany. The investments in the country of destination, including language skills, the decision to immigrate with the complete family as well as the perceived opportunities of the partner to integrate in the country of destination, have a particularly strong influence on permanent settlement intentions. Additionally, the institutional factors in the country of origin and destination are significant predictors of settlement intentions. This includes a broader set of economic as well as social motives accounting for the original migration decision and, in particular, a significant positive relationship between migrants’ rights and permanent settlement intentions. Newcomers provided early with permanent settlement rights or at least with a transparent process towards a secure legal status evidently invest more in their country of destination, subsequently extending the intended duration of stay.

The empirical findings have important implications for adjusting and strengthening labour migration policies addressing demographic skill shortages. One initial finding concerns the greater diversity of regions of origin. Traditionally, Germany as well as most other European countries had a clear preference for labour migrants from geographically and culturally closely related regions (Schönwälder 2004). Recent migrants with long-term attachments to Germany, however, predominantly do not originate from western industrialised countries but—to paraphrase Douglas Massey—are new faces from new places. In addition to the region of origin, three main factors make migrants stay in Germany. Language skills are a first factor, with the results providing empirical evidence for the positive effects of investments in language courses. The second factor addresses the family context: Whereas Europe recently witnessed a turn towards more restrictive family migration policies, these policies are stumbling blocks for migrants’ settlement intentions. Favourable conditions for family reunification and institutional frameworks supporting the partner and other family members to integrate in the country of destination certainly increase the duration of stay. Concentrating on working conditions alone is not going to foster the retention of international labour migrants. Finally, the third factor concerns the legal framework. Labour migrants are highly sensitive to the institutional framework in their country of destination and seriously consider the legal opportunities for their migration decision. Providing them with a swift and transparent process towards permanent settlement rights will increase their duration of stay. Additionally, the provision of more rights will also increase their investments in the country of destination and ease their economic and social integration. The contradictory institutional framework of the 1980s resulted in a lost decade of integration for the original generation of guest worker migrants in Germany (Bade 2001). Establishing clear and transparent legal paths from temporary to permanent residence is a political imperative for future reforms that would have positive effects on the labour market as well as on the integration of new immigrants in the society.

Notes

Besides these three entry gates included in the latter empirical analyses, two additional options for labour migration exist. Section 16 of the Residence Act provides foreign graduates with the option to extend their residence permit by up to 1 year for the purpose of seeking a job adequate to their qualifications (introduced 2005). Secondly, Section 20 of the Residence Act (introduced 2007) offers a special residence title for researchers. This option is rarely used (in 2013 only 930 migrants lived in Germany holding this title) and is not included in the latter empirical analyses.

Response rates for the surveys varied between 21.9 % in the case of self-employed persons, 37.2 % for general labour migrants and 54.1 % for the survey of high-skilled newcomers. All migrants holding one of those three residence titles are labour migrants, whereas potentially accompanying family members would hold separate residence titles. For more information about the data and their sampling procedures, see Block and Klingert (2012) and Heß (2009, 2012).

The focus on those with a maximum duration of stay of 5 years results from the interest in the most recent wave of labour migrants as well as the fact that German immigration law provides for the possibility to apply for a permanent residence title after 5 years of continuous residence in Germany. The sample then becomes increasingly less representative for the group of labour migrants due to these potential status changes.

Although generally seen as an important aspect of economic integration, the latter analyses do not control for working status. Because a job is required for being issued a residence title as a labour migrant, only less than 6 % are currently not employed (due to job loss or other circumstances, e.g. parental leave).

An alternative measure for socio-cultural integration of migrants regularly found in similar analyses is the migrants’ previous experiences in Germany. The multivariate analyses showed, however, that the inclusion of language skills accounts for the same theoretical dimension. Previous experiences were therefore not included in the final analyses.

The detailed results of the factor analysis are available from the authors on request. The reliability of both scales was subsequently tested with Cronbach Alpha of 0.85 in the first and 0.58 in the second case.

The sign and significance of all effects presented on the basis of logistic regressions are controlled by linear probability models to account for potential unobserved heterogeneity (cf. Mood 2010). Binary rather than ordinal logistic regression models were preferred for theoretical reasons but additional linear regression models were fitted on the original dependent variable, confirming reported empirical results. Descriptive statistics as well as results on all additional models are available from the authors on request.

References

Anwar, M. (1979). The myth of return: Pakistanis in Britain. London: Heinemann.

Akwasi Agyeman, E. (2011). Holding on to European residence rights versus the desire to return to origin country: a study of the return intentions and return constraints of Ghanaian migrants in Vic. Migraciones, 30, 135–159.

Bade, K. J. (2001). Ausländer- und Asylpolitik in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Grundprobleme und Entwicklungslinien. Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Bertoli, S., Brücker, H., & Fernández-Huertas Moraga, J. (2013). The European crisis and migration to Germany: expectations and the diversion of migration flows. IZA Discussion Paper, 7170.

Bijwaard, G.E., Wahba, J. (2013). Do high-income or low-income immigrants leave faster? Norface Migration Discussion Paper, 2013–13.

Block, A. H., & Klingert, I. (2012). Zuwanderung von selbständigen und freiberuflichen Migranten aus Drittstaaten nach Deutschland. Ergebnisse einer schriftlichen Befragung von Selbständigen und Freiberuflern nach § 21 AufenthG. Nürnberg: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge.

Borjas, G. J., & Bratsberg, B. (1996). Who leaves? The outmigration of the foreign-born. Review of Economics and Statistics, 78, 165–176.

Carling, J. (2004). Emigration, return and development in Cape Verde: the impact of closing borders. Population, Space and Place, 10(2), 113–132.

Constant, A., & Massey, D. S. (2002). Return migration by German guestworkers: neoclassical versus new economic theories. International Migration, 40(4), 5–38.

Cornelius, W. A., Martin, P. M., & Hollifield, J. F. (1994). Controlling immigration: a global perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Diehl, C., & Preisendörfer, P. (2007). Gekommen um zu bleiben? Bedeutung und Bestimmungsfaktoren der Bleibeabsicht von Neuzuwanderern in Deutschland. Soziale Welt, 58, 5–28.

Dustmann, C. (2003). Children and return migration. Journal of Population Economics, 16(4), 815–830.

Dustmann, C., & Weiss, Y. (2007). Return migration: theory and empirical evidence. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 45, 236–256.

Esser, H. (2006). Sprache und Integration. Die sozialen Bedingungen und Folgen des Spracherwerbs von Migranten. Frankfurt/M.: Campus.

Ette, A., Rühl, S., & Sauer, L. (2012). Die Entwicklung der Zuwanderung hochqualifizierter Drittstaatsangehöriger nach Deutschland. Zeitschrift für Ausländerrecht und Ausländerpolitik, 32(1), 14–20.

Faist, T. (2000). Volume and dynamics of international migration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Faist, T., Sieveking, K., Reim, U., & Sandbrink, S. (1999). Ausland im Inland: Die Beschäftigung von Werkvertrags-Arbeitnehmern in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Nomos: Baden-Baden.

de Haas, H., & Fokkema, T. (2011). The effects of integration and transnational ties on international return migration intentions. Demographic Research, 25, 755–782.

Heß, B. (2009). Zuwanderung von Hochqualifizierten aus Drittstaaten nach Deutschland, Ergebnisse einer schriftlichen Befragung. BAMF Working Paper 28, Nürnberg: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge.

Heß, B. (2012). Zuwanderung von Fachkräften nach § 18 AufenthG aus Drittstaaten nach Deutschland Ergebnisse einer schriftlichen Befragung von Arbeitsmigranten. BAMF Working Paper 44, Nürnberg: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge.

Jasso, G., et al. (2000). The new immigrant survey pilot (NIS-P): overview and new findings about U.S. legal immigrants at admission. Demography, 37, 127–138.

Kalter, F. (1997). Wohnortwechsel in Deutschland. Ein Beitrag zur Migrationssoziologie und zur empirischen Anwendung von Rational-Choice-Modellen. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Khoo, S. (2003). Sponsorship of relatives for migration and immigrant settlement intention. International Migration, 41(5), 177–199.

Khoo, S., Hugo, G., & McDonald, P. (2008). Which skilled temporary migrants become permanent residents and why? International Migration Review, 42(1), 193–226.

King, R. (2000). Generalizations from the history of return migration. In B. Ghosh (Ed.), Return migration: journey of hope or despair? Geneva: International organization for migration and the United Nations.

Levitt, P., & Jaworsky, B. N. (2007). Transnational migration studies: past developments and future trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 129–156.

Martin, P. (2001). There is nothing more permanent than temporary foreign workers. Washington: Center for Immigration Studies.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1998). Worlds in motion: Understanding international migration at the end of the millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Massey, D. S., & Redstone Akresh, I. (2006). Immigrant intentions and mobility in a global economy: the attitudes and behaviour of recently arrived U. S. immigrants. Social Science Quarterly, 87(5), 954–971.

Mood, C. (2010). Logistic regression: why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82.

OECD. (2010). International migration outlook 2010. Paris: OECD.

Pagenstecher, C. (1996). Die ‘Illusion’ der Rückkehr. Zur Mentalitätsgeschichte von ‘Gastarbeit’ und Einwanderung. Soziale Welt, 47(2), 149–179.

Pohlmann, M. (2009). Globale ökonomische Eliten? Eine Globalisierungsthese auf dem Prüfstand der Empirie. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 61, 513–534.

Reitz, J. (1998). Warmth of the welcome: the social causes of economic success for immigrants in different nations and cities. Boulder: Westview Press.

Salt, J., & Clout, H. (Eds.). (1976). Migration in post-war Europe: geographical essays. London: Oxford University Press.

Schönwälder, K. (2001). Einwanderung und ethnische Pluralität. Politische Entscheidungen und öffentliche Debatten in Großbritannien und der Bundesrepublik von den 1950er bis zu den 1970er Jahren. Essen: Klartext.

Schönwälder, K. (2004). Why Germany’s guestworkers were largely Europeans: the selective principles of post-war labour recruitment policy. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27(2), 248–265.

Sjaastad, L. A. (1962). The costs and return of human migration. Journal of Political Economy, 70, 80–93.

Stark, O., & Bloom, D. (1985). The new economics of labor migration. American Economic Review, 75(2), 173–178.

Taylor, J. E. (1999). The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. International Migration, 37(1), 63–88.

Tillie, J. (2004). Social capital of organisations and their members: explaining the political integration of immigrants in Amsterdam. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(3), 529–541.

Waldinger, R. (1994). The making of an immigrant niche. International Migration Review, 28(1), 3–30.

Waldorf, B. (1995). Determinants of international return migration intentions. The Professional Geographer, 47(2), 125–136.

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed in this article are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions to which they are affiliated. The authors greatly appreciate the support of Astrid Schwietering, our colleagues Stine Waibel, Robert Naderi, Stephan Humpert and Elisa Hanganu as well as methodological advice from Markus Ganninger in calculating the post-stratification weights of the applied dataset as well as to participants of the “highly skilled migration, gender and family” session at the International Conference on Population Geographies 2013 in Groningen. They provided helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ette, A., Heß, B. & Sauer, L. Tackling Germany’s Demographic Skills Shortage: Permanent Settlement Intentions of the Recent Wave of Labour Migrants from Non-European Countries. Int. Migration & Integration 17, 429–448 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0424-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0424-2