Abstract

Migrants’ labour market trajectories are seldom explored from a longitudinal, comparative perspective. However, a longitudinal approach is crucial for a better understanding of migrants’ long-term occupational attainments, while comparative research is useful for disentangling specific features and general processes across national groups and destination and origin countries.

This chapter uses the MAFE data to explore the labour market outcomes of Senegalese, Congolese and Ghanaian migrants in different European countries and those who have returned from Europe, matching their occupational attainments before, during and after migration. It will also examine the different forms of migrants’ transnational engagement and how they change over time and with integration in the destination countries.

The results suggest patterns of self-selection for specific destination countries, with students and skilled workers heading mainly to ‘traditional’ destinations (former colonial countries), and the less educated and low-skilled to ‘new’ migrant–receiving countries. Analysis reveals a dramatic downgrading upon entry into the European labour market. However, while the overall incidence of mismatch decreases over time, this is hardly the result of upward occupational mobility of qualified migrants downgraded upon arrival; rather, it reflects the entry of students into the labour market, compensating for the underperformance of skilled workers. Labour market participation in destination countries also appears strongly affected by gender, with a higher rate of female inactivity upon arrival and a persistent risk for women of returning to inactivity at later stages. The chapter shows that the facts do not unequivocally confirm the common image of return migration as a “triple win situation” for individual migrants, destination countries and origin countries. Senegalese and Congolese return migrants seem to regain a similar status to the one they had before leaving their country of origin, showing a ‘brain regain’, while the Ghanaian case suggests a positive link between migrants’ economic integration at destination and their re-insertion in Ghana upon returning (mainly from UK). Finally, the chapter presents trends in three different forms of transnational economic contribution by migrants – private investments, remittances and association membership – during the stay abroad, providing evidence of the linkages between migrants’ occupational trajectories abroad and their levels of transnational engagement.

Authors’ contributions to the chapter were as follows: Eleonora Castagnone was in charge of the framework of analysis for the chapter and wrote the Introduction, Sects. 5.2, 5.3, 5.4 and the Conclusions; Laura Bartolini wrote Sect. 5.5 and contributed to the Conclusions; Tiziana Nazio was the person at FIERI in charge for the analyses design and contributed to Sect. 5.1, Bruno Schoumaker was in charge of the analysis design and production. We also thank Cora Mezger, Nirina Rakotonarivo, Sorana Toma for contributing ideas to the analysis of the chapter and Cris Beauchemin, Douglas Massey, Hugo Graeme and Ferruccio Pastore for their valuable and constructive critical comments to the chapter.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

This chapter explores patterns of labour market integration by African migrants in Europe, the re-integration of returnees in origin countries and their transnational economic contributions whilst abroad. To do this we analyse migrants’ transnational employment trajectories before leaving, during their time in Europe and upon return, and also the ways in which they participate economically in their origin countries during their time abroad.

The labour market integration of migrants at destination and their economic re-integration at origin are crucial issues in the current academic debate and a major concern for policy makers in Europe and Africa. In Europe it is crucial in order to maximize the benefit of migrants’ human capital and so stimulate growth and productivity and also in order to promote social cohesion; in Africa it is crucial in order to enhance the potential of migrants and returnees as key players for the development of their origin countries (Black and King 2004; Van Hear and Sørensen 2003; Sjenitzer and Tiemoko 2003).

However, the study of migrants’ economic outcomes has been embedded in two distinct fields of study and theory and is dealt with empirically as two separate subjects, depending on whether migrants are viewed from the receiving or sending countries’ viewpoints.

From the receiving countries’ perspective, migrants’ integration into the labour market at destination is covered by the literature on integration and social cohesion and on determinants and outcomes of migrants’ economic integration at destination.

Skill mismatch has become a growing concern among scholars and policy makers as it has important economic implications for individual migrants, as they do not receive a salary commensurate with their abilities; for firms, as it reduces productivity and increases on-the-job search and turnover; and at the macroeconomic level, as it generates a loss of human capital (brain waste) and a reduction in productivity and efficiency (Quintini 2011).

However, the existing literature on labour market mismatch among migrants does not appear to have explored work experience prior to migration, particularly the phenomenon of an education-occupation mismatch in the home country before migrating (Piracha et al. 2012), or how this phenomenon relates to later outcomes in receiving countries. Comparing the education-occupation mismatch before and after departure is crucial for understanding the extent to which migration is rewarding for migrants in terms of opportunity to put their skills to use.

Furthermore, few studies have taken a longitudinal approach to their analysis of migrants’ labour market attainments, providing a dynamic picture of their economic integration in receiving countries (Lubotsky 2007; Duleep and Dowhan 2008). While common wisdom suggests that migrants face initial disadvantages upon arrival in the labour market at destination, their outcomes are expected to improve over time (OECD 2007). Yet there is increasing evidence that migrants may face persistent labour market barriers that threaten their full integration, and that patterns of economic integration vary markedly according to country of origin (Münz 2008; Borjas 1999; Portes and Rumbaut 2006) and country of destination (Münz 2007; Dustmann and Frattini 2010). Little comparative research has been done on the long-term labour market performance of the migrant workforce across the different EU member states taking into consideration differences in employment, economic performance and integration of different national groups.

On the origin countries’ side, a separate strand of literature has mainly concentrated on the links between migration and development (Kabbanji 2013). From the perspective of sending countries, which invested in the education and training of each migrant, the outflow of highly skilled nationals (brain drain) constitutes a heavy financial burden as they lose some of their better educated individuals (Kohnert 2007), especially when educated migrants cannot obtain skilled jobs in their destination countries and can make little use of their skills and knowledge (brain waste). While brain drain can be potentially disruptive for sending countries, the circulation and return of skills may positively impact on their development (Ghosh 2000). But the extent to which this happens depends heavily on patterns of integration into the labour market in Europe (de Haas and Fokkema 2011; Shima 2010) and on the transnational links migrants may be able to maintain with their origin country whilst abroad (Cassarino 2004). In the migration and development discourse, migrants’ remittances and other transnational activities are often deemed to play a crucial role at origin, positively contributing to the development of households and national economies. The depth of a migrant’s transnational links depends on their characteristics and those of their household, and on the success of their migration project in terms of integration into the labour market at destination.

Although increasing attention is being paid to return migration and the challenges of migrants’ economic reinsertion, little research has taken into account the economic trajectories and achievements returnees experienced prior to migration and during their time in Europe, or the skills and qualifications they may have acquired whilst abroad (Ammassari 2004). This is also due to some major methodological gaps and data shortage. Statistical data are usually collected and made available for single countries (Wimmer and Schiller 2003: 210), through censuses and surveys, and on a cross-sectional basis. One-off studies still prevail, focusing on specific events (transitions from study or inactivity to employment, etc.) or specific phases of the migration process (settlement and integration in destination country; temporary returns and circulation between sending and receiving countries; permanent return to origin country), often disregarding the trajectory as a whole (King et al. 2006).

As available data are mainly cross-sectional and collected at country level, they seldom allow matched analyses of migrants’ long-term occupational attainments between origin and destination countries, before migrating, upon arrival, after initial settlement at destination and upon return. Furthermore much of the research is focused on individual migrant groups in particular places, providing in-depth information on single cases, but failing to provide more general and contextualised information, while comparative research would be necessary in order to disentangle specific features and general processes across national groups, destination and origin countries, and different populations (migrants, returnees, non-migrants).

Some biographic surveys have already filled some of these research gaps. The Mexican Migration Project (MMP) has built a major longitudinal biographic dataset, generating numerous insights into the patterns of economic integration and transnational behaviour of Mexican migrants in the United States (Massey 1987). It was later extended to other Latin American countries through the Latin American Migration Project. Other longitudinal studies of migrants’ (economic) integration at destination include the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada (LSIC), the longitudinal survey on the Settlement of New Immigrants to Quebec (ÉNI: Établissement des Nouveaux Immigrants) and the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Australia (LSIA) (for a review, see Black et al. 2003). In Europe, however, very little research has been undertaken with such longitudinal, matched, cross-country approaches. As a result, there is a lack of solid scientific evidence and sound guidelines for European and national policies on the long-term transnational economic performances of migrant workers between origin and destination countries.

The purpose of this chapter is to explore longitudinally the labour market outcomes of African migrants and returnees, looking at different stages in the migration process, considering labour trajectories before leaving, at arrival and during migrants’ time in Europe, and upon return.

The chapter addresses the following questions: How do immigrants’ careers unfold during their first years after arrival? Do African migrants find jobs in Europe that match the levels of skill they arrived with? Does their employment situation change over time? To what extent do their experiences differ from one destination country to another? What role does gender play in such outcomes? To what extent are returning migrants reintegrated into local labour markets? What is the educational level of those who come back? Lastly, the chapter examines to what extent African migrants are engaged in transnational activities. It explores their attitudes to sending remittances, investing back home and participating in development associations, as well as how these attitudes change over time and in relation to their integration in the destination country in terms of legal and occupational status.

2 The MAFE Data

From this perspective, the MAFE longitudinal and multi-sited data (see Chap. 2 for further details) present some major advances, as they allow us to:

-

investigate retrospectively the life-long labour trajectories of the individuals in the samples, at different moments of their lives and throughout their time in different countries they may have lived in;

-

retrace the different forms of individuals’ transnational economic participation, such as remittances, participation in development associations and investments in the origin country;

-

cross these data with variables on occupational and legal integration in the destination country;

-

compare different populations: migrants, non-migrants and migrants who had returned to the sending countries at the time of the survey;

-

compare different national groups of migrants: Senegalese, Congolese and Ghanaian;

-

compare different destinations in Europe: France, Italy and Spain for the Senegalese; Belgium and UK for the Congolese; Netherlands and UK for the Ghanaians.

In our analysis of migrants’ occupational trajectories we decided to take into consideration key stages in migratory paths, such as the year before the first departure to Europe, the first year of arrival and the following years in Europe up to ten years of stay. For returnees, we focused on the last year before leaving Europe, the first year back in the origin country and the year of the survey. Focusing on key migration events (e.g. exit from or entry to a country) and on fixed years of the migration experience, rather than comparing respondents’ trajectories by calendar year (e.g. 2005) or period (e.g. 2000–2010) made it possible to compare different groups, migration time frames and receiving contexts, or at least reduced the complexity and heterogeneity of these factors. This gives us a better grasp of the structure of the main pathways of labour market integration for the three African groups. However, this choice leads to analysing similar events (e.g. entry into the labour market in the first year of arrival at destination) regardless of timeframe; for instance, no distinction is made between migrants who arrived in Europe in the 1980s and those who arrived in much more recent times, when the historical, socio-economic and legal frameworks were very different. It should also be taken into account that analyses based on retrospectively collected data are based on “survivors” in the sampled countries: less successful trajectories are more likely to bring about a further migratory step (either to a new destination country or a return), and thus become increasingly under-represented with the passage of time.

The key variable analysed in this chapter is occupational status, distinguishing between “skilled” and “unskilled” workers (whether formally and informally employed); “unemployed”; “inactive” (i.e. individuals not actively looking for a job or active in unwaged occupations such as reproductive tasks), and “students” enrolled in training or formal education courses. The variable is computed on the basis of two questions in the biographic questionnaire, for each stage in the respondent’s trajectory: (i) a multiple-choice question about labour market status (study, economically active, unemployed, various inactive statuses); and (ii) for those in work, an open question that recorded in detail the occupation, tasks performed, sector, etc. The information provided was subsequently coded using a three-digit occupational classification adapted from ISCO-08.

All biographic data, including information on occupational status, were collected on a yearly basis. Where status had changed during year (for instance changes of job or short periods of unemployment between jobs) or multiple jobs were held at the same time, the survey registered the one considered the main status or the main job (either the longest one, or the one regarded as the prevalent one). As a result, trajectories may be over-simplified, with occupational spells shorter than a year and second jobs not taken into consideration in the analysis. Finally the survey did not record whether the jobs reported by the migrants were performed with or without a regular contract; this prevents any analysis of the presence, magnitude and characteristics of undeclared jobs within the sample.

Section 5.3 deals with African migrants’ integration into the European labour market, exploring their labour market outcomes and trajectories over time. This part highlights the composition of migrant flows at the moment of departure, looking in particular at migrants’ last occupational status in the year before leaving, by origin and destination country. Their labour trajectories are then considered for their time in Europe (up to first ten years of stay), looking at how migrants’ careers unfold across time, by origin and destination country. Labour market integration pathways are also explored by gender across the six European host countries, highlighting the very different outcomes between men and women.

Labour market re-integration in the origin countries of returnees from Europe are then considered, comparing the employment outcomes of returnees at different times of their lives and vis-à-vis the non-migrant population at the time of the survey. Lastly, migrants’ economic contributions to origin countries and their transnational activities while abroad are discussed, presenting data on individual investments at origin, remittances to origin household and membership in local associations. Lastly some conclusions are drawn on the basis of the findings presented.

3 Not at Random. Migrant Workers’ Profiles According to Destination Country in Europe

The first step in our analysis of employment trajectories is to analyse the profiles of migrants prior to departure, looking at their occupational status in the year before leaving, by origin country and destination country (see Fig. 5.1, far left column of each graph).

Occupational status in the last year in Africa and in the first and tenth years of stay in Europe, by country of origin and of destination

Source: MAFE-Senegal biographic survey in France, Italy and Spain; MAFE RDC biographic survey in Belgium and UK; MAFE Ghana biographic survey in UK and the Netherlands

Population: Current migrants in France, Italy and Spain, Belgium, UK and the Netherlands; weighted data

Interpretation: The figures show the distribution of the last occupational status of migrants in Senegal, RDC and Ghana before leaving (far left column in each figure) and the distribution of migrants’ occupational statuses in the destination countries in the first and tenth years of their stay

Results from our samples suggest that migration flows to the more recent migration countries are mainly composed of low-skilled workers. Senegalese in Spain and Italy were mainly employed as unskilled workers before leaving (72.2% and 60.8% respectively), while only 34.4% of those migrating to France were low- or unskilled workers prior to departure. Migrants from Ghana having left their origin country as unskilled workers and residing in the Netherlands also largely outnumber the skilled ones, accounting for over 50% of the total for this group, while those migrating to the UK show an inverse proportion, with 42.7% reporting skilled occupational status before leaving and 22.9% unskilled status.

Congolese migration is the exception; here we find a high proportion of students in both host countries (around 25%), with about 20–30% of the total being non-working individuals (inactive plus unemployed). This reflects the particular circumstances of migration for this group, many of whom left the Democratic Republic of Congo as asylum seekers (see Chap. 7).

In contrast to more recent destinations, migration to traditional destinations involved much higher proportions of persons who were students or in skilled occupations in the year prior to departure. Among Senegalese in France, Congolese in Belgium and UK and Ghanaians in the UK, students were between 24% and 28% immediately before leaving. Colonial links thus seem to be a crucial factor in determining the composition of migration flows, particularly owing to opportunity structures for citizens from former colonies, such as shared language, similar education systems and recognition of educational credentials from the former colony.

Another factor encouraging the choice of the former colonial country as a destination for study is the greater availability of student grants, often combined with other facilities such as student residences, documents, housing and economic support. Former colonial powers have always favoured the migration of students from former colonies as part of the global package of foreign aid; providing higher education for foreign students has been an important channel for host countries to disseminate their cultural, economic and political norms abroad (Beine et al. 2013). Established networks of highly-skilled working migrants and students in these receiving countries can also play a crucial role for people arriving from the origin country (ibid.).

Students and the highly skilled seem thus been more inclined to have chosen former colonial countries as their destination. Given this framework, the structural opportunities offered by the receiving countries can also be expected to positively impact the students’ subsequent employment careers, shaping their integration into the labour market at destination.

4 What Happens Next. Post-arrival Labour Market Trajectories in Europe

Given that the composition of the flows to different destination countries varies in terms of employment profile, with Congolese and Ghanaian migrants in Europe more often having been in higher-skilled occupations prior to departure than their Senegalese counterparts, Figs. 5.1 and 5.3 analyse how migrants’ careers unfold after arrival and to what extent migrants’ experiences differ across destination countries.

Results for long-term outcomes by destination country within each origin-country flow suggest that here too the pathways for labour market integration differ between new and old host countries (again with an exception for migrants from DRC). Most Ghanaian migrants in the Netherlands and Senegalese in Spain and Italy enter the labour market in unskilled jobs and stay in such jobs (see distribution of occupational statuses at year 1 and 10 in Fig. 5.1 and labour trajectories in Fig. 5.2). This may mean staying in the same unskilled job or changing to another job at the same skill level, but anyway implies a persistent stagnation in the lower segments of the labour market.

Migrants’ five most frequent sequences of occupational status during their stay in Europe (%), by country of residence (possible statuses: Unskilled, Skilled, Unemployed, Inactive, Student)

Source: MAFE-Senegal biographic survey in France, Italy and Spain; MAFE DRC biographic survey in Belgium and UK; MAFE Ghana biographic survey in UK and the Netherlands

Population: Current migrants in France, Italy, Spain, Belgium, UK and the Netherlands; weighted data

Interpretation: The figure shows the most frequent sequences of occupational status for each of the three migrant groups. Horizontal mobility trajectories (implying job changes within the same status) are not tracked here: if an individual has changed from one unskilled job to another, his/her trajectory will be registered as a single “Unskilled” sequence

Of migrants who were working in skilled occupations before migrating, the overwhelming majority experienced a drastic downgrading upon entry to the European labour market in all the sampled European countries, as shown in Fig. 5.1, where the proportion of African workers in skilled positions routinely drops in the first year of stay in Europe.

For Congolese in both the European host countries, Ghanaians in the Netherlands and Senegalese in Spain, the proportions of skilled workers subsequently recover over time, though without returning to the levels they stood at before departure. For Senegalese in France and in Italy and Ghanaians in the UK, however, the proportions of migrants in skilled occupations reach higher levels than before arrival in Europe (see proportions of skilled workers in last year in origin country and in year 10 of stay in Europe).

In the UK, for migrants from Ghana in particular, skilled migrants experience less downgrading upon arrival in Europe and by the tenth year a higher percentage are in skilled jobs than before leaving home. Although the UK is a more recent destination for Congolese migrants, with higher linguistic barriers and weaker social networks, for this group too it provides comparatively better access to skilled jobs.

However, although we found evidence of upward mobility trajectories in the destination countries (Unskilled→Skilled sequences in Fig. 5.2), the increase in the proportion of migrants in skilled jobs across the destination countries is mainly explained by students’ post-studies entry into the labour market in skilled positions, compensating for the skill mismatch of migrants who arrived with skills. In other words, a migrant has a much higher probability of obtaining a skilled job if he/she has spent time as a student in the destination country (Student→Skilled sequence), rather than entering as an already skilled worker (Skilled sequence for those who entered the labour market as skilled workers; Unskilled→Skilled sequence for those who were either underemployed upon entry and afterwards caught up, or experienced an upgrade once in Europe).

Nonetheless, the data also show that a certain proportion of students do not achieve upward occupation mobility but join the labour market in unskilled occupations or fall into unemployment or inactivity (Student → Unskilled; Student → Inactive; Student → Unemployed).

4.1 In and out of the Labour Market: Gendered Trajectories Involving Inactivity and Unemployment

In order to better grasp the dynamics of economic integration at destination it is important to understand how gender affects migrants’ trajectories and labour market participation.

As the MAFE data show, before leaving their origin countries male migrants are much more likely to be involved in waged labour than are female migrants, especially among the Senegalese and Congolese, as shown in the far left column of each chart in Fig. 5.3. Rates of inactivity in the year prior to departure are 31% for women vs. 4% for men among the Senegalese and 20% for women vs. 3% for men among the Congolese, while the Ghanaian rate for women (5%) is close to that for men (2%). This reflects differences between the three origin countries in the organisation of gender relations and family life and may point to a selection effect among women migrating to different countries.

Occupational status in the last year in Africa and at each year of stay in Europe (for the first ten years), by gender

Source: MAFE-Senegal biographic survey in France, Italy and Spain; MAFE DRC biographic survey in Belgium and UK; MAFE Ghana biographic survey in UK and the Netherlands

Population: Current migrants in France, Italy and Spain, Belgium, UK and the Netherlands; weighted data

Interpretation: The figures show the distribution of the last occupational status of migrants in Senegal, DRC and Ghana before leaving (far left column in each figure) and the distribution of migrants’ occupational statuses in the surveyed countries in their first and tenth years of stay

Ghanaian women are less likely than Congolese or Senegalese to come to Europe for family reunification, and are more likely to come as students to the UK (see Chap. 3). As shown in Chap. 11, Ghanaian migration has become increasingly feminized with more women migrating independently of men to fulfil their own economic needs, with professional women, especially nurses and doctors, increasingly engaged in international migration (see Chap. 11).

Unemployment and inactivity rates are much lower for Ghanaian women than for women from Senegal or DRC, from before departure and throughout their stay abroad. In terms of labour outcomes at destination, the Ghanaian migrant population is also far more gender-balanced than the Senegalese and Congolese, with men and women experiencing similar career paths.

In Senegal women receive less education and are less involved in the formal labour market, while they are more engaged in informal activities and in unwaged labour (Fall 2010). While there is a growing, albeit slow, feminisation process in migration from Senegal, migration from this country is still undertaken mainly by men, with women very much relying on their families to decide on and organise their migration plans. This aspect is also crucial to the construction of subsequent labour trajectories in Europe.

Congolese women participate in the labour market more than Senegalese women and more often migrate autonomously (Toma and Vause 2011). Among Congolese migrants, unlike the Ghanaian and the Senegalese, inactivity also significantly affects men. As mentioned before, this may reflect the fact that many Congolese have migrated as asylum seekers rather than as economic migrants in the conventional sense.

On entry to Europe, for all three groups, the rate of female inactivity shows an increase, reflecting the reason for or mode of migration (more frequently than for men on grounds of family reunification). The rate then declines for Senegalese women, who increasingly tend to become employed over time in the receiving countries (see Chap. 14); it remains constant for Congolese women (see Chap. 8) and even slightly increases for Ghanaian women (see Chap. 11).

With regard to education, for all three countries, overall, women’s probabilities of coming as students and of engaging in periods of education abroad are not very dissimilar to those of men. Senegalese women are even slightly more likely to undertake education or training in Europe than their male counterparts, unlike Congolese and Ghanaian women.

4.2 How Qualifications Compare with Jobs in Europe

The above analyses have already shown a systematic and persistent downgrading in the European labour market for skilled migrants. To investigate this issue further, Fig. 5.4 shows, for working migrants from DR Congo, Ghana and Senegal, how far their educational levels are matched by their employment positions in the year prior to migration and across their first ten year of stay in Europe.

Proportion of individuals with higher education working in unskilled occupations in the last year before migrating and in their first ten years in Europe

Source: MAFE-Senegal biographic survey in France, Italy and Spain; MAFE DRC biographic survey in Belgium and UK; MAFE Ghana biographic survey in UK and the Netherlands

Population: Current migrants in France, Italy and Spain, Belgium, UK and the Netherlands; weighted data

Interpretation: The figure shows the percentage of individuals with higher education diplomas but employed in low-skilled jobs, at each year of their stay in Europe, for the first ten years

The data show high levels of education-occupation mismatch (i.e. of individuals with higher education working in unskilled jobs) prior to migration, to varying degrees: 13% among migrants from DRC, 27% from Senegal and 39% among Ghanaian.

The incidence of mismatch rises dramatically upon entry to the host country, mirroring the occupational downgrading shown in Fig. 5.1, reaching its peak in the first year of stay for the Senegalese (91%) and Congolese (64%), and in the third year for the Ghanaians (69%).

In subsequent years, the incidence of education-occupation mismatch decreases rapidly until the 6th year of stay in Europe (around 50% for all three groups) and then continues to decline, but at a slower pace. This means that, after an initial downgrading, migrants’ repositioning in the labour market to a level that matches their skills takes place mainly within the first 5–6 year of stay in Europe, while those who have not managed to upgrade their occupational niche within this time will have less possibility of doing so in subsequent years of their stay abroad.

Comparison of the longitudinal trends for the three groups shows that overall, migration has mostly not been rewarding for skilled individuals from the three African countries. If we compare the two ends of the trajectories covered, i.e. the status before leaving and after ten years of professional experience abroad, we find a zero-sum game or even a loss in terms of labour market outcomes. Mismatch in origin country and at destination after ten years of stay is similar for Senegalese and Ghanaian migrants, with a slight increase for the first group (27% prior to migration and 32% after ten years abroad) and a slight decrease for the second (39% before leaving and 36% after ten years of migration), while Congolese skilled workers, who showed the best economic performances in the country of origin, are the ones who experienced the most disruptive and persistent downgrading across time (from 13% over-qualified before leaving to 45% after ten years of stay). This low performance is probably linked to the fact that many Congolese migrants come to Europe for non-economic reasons, as asylum seekers.

5 Post-return Labour Market Re-integration in Origin Countries

Here we analyse the occupational trajectories of return migrants, comparing their outcomes in the origin country before migrating, in last year in Europe before returning, in the first year upon return and in the year of the survey in the origin country. Returnees in the MAFE survey –unlike in the previous part- were sampled and interviewed in the three African countries and only migrants having come back from European destinations are considered in these analyses (see Annex).

Occupational status upon return, shown in Fig. 5.5, suggests that most returnees join the labour market after returning to their origin country, while return migration in connection with retirement from the labour market (expressed as inactive status) does not appear to be frequent. This is partly linked to the age distribution of the sampled population, which comprised mostly individuals younger than the retirement age (see Annex).

Occupational status in last year in Africa, last year in Europe, first year after returning, and survey year (all returnees from Europe)

Source: MAFE-Senegal biographic survey in Senegal; MAFE DRC biographic survey in Congo; MAFE Ghana biographic survey in Ghana

Population: Return migrants and non-migrants interviewed in the surveyed regions and cities in Senegal, DRC, and Ghana; weighted data

Interpretation: Distribution by occupational status at four points in time for returnees, compared with the distribution by occupational status of non migrants at survey time

For returnees to Ghana and Senegal there is an increase in unemployment immediately after return (from 4.3% before leaving Europe to 10.6% upon return among Ghanaians and from 1.8% to 15.4% among Senegalese). The interruption in their local labour market experience and weakened social network ties in the origin country, coupled with the downgrading of their occupational status abroad, may hamper a smooth reintegration into urban labour markets at least in the first period upon return (Mezger and Flahaux 2010). Over time, returnees seem to find a way out of unemployment, which at the time of the survey stood at 3.3% among Senegalese returnees and 8.2% among Ghanaian returnees.

Among Congolese returnees, although their rates of both unemployment and inactivity while abroad were higher than for the Ghanaians or Senegalese, unemployment also decreases in the years after returning (from 12.9% upon return to DRC to 8.0% at the time of the survey).

Compared to the last year in Europe, the percentage in skilled jobs increases considerably from the very first year after return, in all three countries of origin (from 12.3% in last year in Europe to 57.2% upon return among Congolese; from 16.8% to 60.2% among Ghanaians; from 3.8% to 22.3% among Senegalese).

However, in the case of Senegal and DR Congo, occupational skill levels upon return are similar to those held before migration and the slight differences are mainly due to a change from pre-migration student status (Senegal) or inactivity (DR Congo) to employment. This means that all in all returnees experience a “brain regain”, rather than a “brain gain” through knowhow and skills acquired while abroad: the returnee profile, and in particular the percentage of skilled workers, reflects the profile of migrants before leaving. However, given the very broad categories of “skilled” and “unskilled” labour adopted here, while the percentages are the same, migrants’ competencies and skills might be different in nature on their return as they have probably acquired different competences while abroad compared to never-migrants.

The case of Ghana once again stands out, with Ghanaian returnees performing better than the other groups on re-integrating the home labour market. The percentage in skilled work increases after return, and is higher than before migration (37.1% before migration to 60.2% upon return and 55.8% at the time of the survey). This pattern could be due to returnees who completed their studies abroad having better access to higher-level jobs once they are back in Ghana. An additional explanation is that, returning mainly from the UK where their economic integration was better overall (Fig. 5.1), Ghanaians may have brought back higher-level skills and professional experience from there. This hypothesis should be explored further; if confirmed, it would support the thesis of a positive link between labour market outcomes at destination and positive re-insertion in the economic context at origin.

In all three countries, the overall integration of returnees in the labour market shows better outcomes than for individuals who never migrated. Especially in DR Congo and Ghana, we observe both considerably smaller shares of returnees in unskilled occupations or inactive (Congo: returnees 12.8% unskilled and 0.9% inactive vs. non-migrants 51.8% unskilled and 6.7% inactive; Ghana: returnees 23.6% unskilled and 10.6% inactive vs. non-migrants 61.5% unskilled and 13.3% inactive). Though less pronounced, the general pattern is similar in the case of Senegal (returnees 43.7% unskilled and 16.3% inactive vs. non-migrants 51.9% unskilled and 28.9% inactive).

Nonetheless, the migration experience itself is not the only driver of this advantage on the labour market, or the main one. Positive (self)selection is at work. Returnees were comparatively more likely to be in skilled occupations already before migrating, indicating a strong selection effect both at first out-migration and at return. The difference between non-migrants and return migrants who had been to Europe seems to be primarily related to the particular characteristics of individuals who migrate internationally and, later, decide to return. To a certain extent, it may also be related to the benefits of migration such as access to education (see students’ trajectories in Figs. 5.1 and 5.2) and the ability to save money. However, the relative weight of these two factors should be carefully assigned; as both are likely to play a role, their relevance should be explored further.

6 Migrants’ Economic Contributions to Origin Countries

Migrants’ economic contributions to origin countries take many different forms and vary with the type and length of the stay abroad and the degree of integration into the labour market at destination at different stages of their life there. Depending on the migrant’s occupational and economic trajectories whilst abroad, transnational economic activities range from occasional contributions to the origin household when particular circumstances arise to long-term commitment to productive and social investments in the origin area.

Several hypotheses have been put forward concerning how transnational behaviour evolves over time in the destination country and how it is related to migrants’ characteristics in terms of gender, education, employment conditions and household composition at origin and at destination. The attitudes of migrants who consider their experience abroad to be permanent, progressively increase their economic engagement with the destination country and proceed with family reunification there, can be expected to differ from those who consider the possibility of return or of circulating between the origin and destination countries.

Highly-skilled migrants may make fewer contributions at home if they come from wealthier households that do not need an external source of income. Or they may engage in larger and more complex investments at home because they are earning more and have a better understanding of savings management. Economic contributions may also depend on the migrant’s legal status: undocumented migrants may earn less on average than documented ones, but they are more likely to transfer earnings to their origin countries because the lack of documents may hinder access to the savings and investment market at destination. Establishing what characteristics and motivations of migrants and households determine the level of a migrant’s economic engagement with the origin country is an empirical exercise.

In this section we use the MAFE data to explore three distinct levels of migrants’ economic contributions to origin countries while they are abroad. At the individual level, migrants can invest in buying assets in the origin country with the aim of maintaining a link with the home country. The acquisition of assets can act as insurance, open up further economic possibilities for a potential return and reintegration, and provide additional financial resources for productive and investment purposes in the origin country.

Secondly, migrants often transfer money to their households in the origin country. Remittances are perhaps the best understood of migrant’s transnational activities and certainly play a crucial role in most migrant sending countries, contributing to GDP at the macro-level and providing an additional income source for origin households at the micro-level.

A third type of economic contribution is participation in collective development initiatives through membership of associations in the origin country. Membership as identified in the MAFE data implies that migrants “pay contributions or membership fees to one or more associations (including religious organisations) that finance projects in [the origin country] or support [...] migrants in Europe.” Hence, migrants’ contributions may be designed to feed into local development actions at origin or to provide services to co-nationals abroad.

These three types of transnational engagement are part of reciprocal social relations between migrants and their origin households and, often, an interplay between the two. In some cases they represent a significant contribution to the origin household and to a migrant sending country as a whole (Piper 2009). Considering these flows and activities within a framework of reciprocal relations and empirically examining how they vary among different migrant communities in Europe we can achieve a better understanding of the potential impact of migration on origin households and on the surveyed countries in Africa (de Haas 2008).

6.1 Assets, Remittances and Association Membership: Commitment Increases Over Time

Figure 5.6 shows the MAFE data on the average level of transnational economic activity by migrants, as reported by Congolese, Ghanaian and Senegalese migrants at the time of the survey in Europe (2008–2009). Assets owned in the origin country that are recorded in the MAFE survey include construction land, agricultural land, dwellings and businesses. The results presented refer to the average number of assets owned per migrant. With regard to remittances, migrants are recorded as remitting in each year for which they report having regularly sent money to a recipient in the origin country. Hence, although our data do not capture the total amount of money sent or the frequency of the transactions, we can pinpoint the proportion of migrants who are remitting at different times during their stay abroad. From a question about contributions or membership fees paid to associations in the origin country we can identify the proportion of migrants involved in local or migrants’ associations at different points in time.

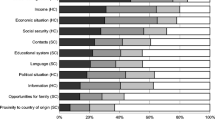

Mean number of assets owned per migrant, proportions of migrants sending remittances and paying association contributions at the time of the survey

Source: MAFE-Senegal biographic survey in Senegal, France, Italy and Spain; MAFE DRC biographic survey in Congo, Belgium and UK; MAFE Ghana biographic survey in Ghana, UK and the Netherlands

Population: Current migrants in France, Italy and Spain, Belgium, UK and the Netherlands; weighted data

Interpretation: the graph shows the average number of assets owned per individual, the percentage of individuals sending remittances and the percentage contributing to associations at the time of the interview, for Senegalese Congolese and Ghanaian migrants living abroad at the time of the survey

In general, transnational activities and support for origin households and communities seem to be an important aspect of the migration experience. The migrant samples from all three origin countries include a high proportion of remittance senders (between 60 and 80% remitted regularly at the time of the survey), and the number of assets owned per migrant is significant, especially among Ghanaians (more than 1 asset per migrant in the sample). A smaller but relevant proportion of migrants are involved in associations at origin.

These activities are better understood if analysed from a longitudinal perspective, with the average level of economic contribution of migrants from the very beginning of their stay abroad. To compare longitudinal trajectories in a more precise way, Fig. 5.7 compares the same indicators (asset ownership, remittances and association contributions) at two points in time: at the beginning of the migratory experience and after ten years of stay in Europe. Furthermore, the data are disaggregated by (a) employment status, (b) gender and (c) legal status. As is consistent with a progressive integration into the labour market at destination, levels of all the three types of economic engagement increase between the time of arrival in Europe and the time of the survey (see Chaps. 8, 11 and 14).

Migrants’ economic contributions to origin countries at start of migration trajectory and after 10 years of stay in Europe: assets, remittances and association contributions by (a) employment status, (b) gender and (c) legal status

Source: MAFE-Senegal biographic survey in Senegal, France, Italy and Spain; MAFE DRC biographic survey in Congo, Belgium and UK; MAFE Ghana biographic survey in Ghana, UK and the Netherlands

Population: Current migrants in France, Italy and Spain, Belgium, UK and the Netherlands (see Table 1); weighted data

Interpretation: The first figure of each row shows the mean number of assets owned per migrant at two points in time: the last year before migration and the tenth year of stay in Europe, according to (a) employment status, (b) sex and (c) legal status. The second and third figures present the percentages of sampled migrants sending remittances and being members of associations in the origin country at two points in time, the first and the tenth year of stay in Europe, by (a) employment status, (b) sex and (c) legal status

Employed migrants show higher levels of transnational engagement and a greater increase than non-employed migrants. Asset ownership starts from a very low level for all the three groups but increases markedly more for the employed than for the non-employed. Senegalese employed migrants reach a peak of 85% sending remittances, while non-employed ones stick at 54%. Nevertheless, those who declared not being in employment also increased their level of engagement during their stay abroad and between 45 and 56% of them were sending remittances during their tenth year in Europe.

As regards gender differences, patterns of transnational activity are consistent with the data on labour market participation among men and women before migration and during their stay abroad, discussed in the previous section. While the level of transnational activity increases for both men and women, the level reached after ten years abroad is often markedly different. Ghanaian migrants show the most balanced situation across gender, with women surpassing men in the average number of assets owned and in the proportion contributing to associations. Senegalese women are less likely to invest in assets or to remit than their male counterparts. Congolese migrants present a more mixed situation: women are more likely to send remittances but are less engaged in private investments and local associations.

As to legal status, Fig. 5.7c shows differences between those undocumented at arrival and those who started their stay in Europe with documents. Undocumented migrants are less likely to engage in transnational activity, with the relevant exception of undocumented Ghanaians who tend to invest more and to participate more in migrant associations, even at the time of arrival.

To sum up, remittance transfers are the most common practice for all three origin groups, followed by investment in assets in the origin country. The high proportion of remitters among the undocumented may testify to the need to transfer earnings abroad since access to the formal bank and savings market is prevented at destination. In the case of Congo, low levels of investment in assets after migration and of participation in associations may be due to the lack of security for persons and businesses in that country and to the fact that not many Congolese migrants intend to return (see Chap. 3).

As regards contributions to associations, while the higher average level among Ghanaians could be connected with their strong involvement in religious organizations, it may also be the case that our data underestimate the actual level of engagement in organizations and associations. As the MAFE survey only asked whether respondents paid formal membership fees, and so excluded other, non-formal forms of membership or contribution, it may not have captured African migrants’ widespread participation in informal networks, often of religious inspiration (for example Murid Muslim network membership among Wolof migrants: see Sakho 2013).

7 Conclusions

This chapter explored the long-term effects of migration on the labour market outcomes of Africans in selected European destinations, by considering their overall transnational labour trajectories before leaving, during migration, and upon return. The chapter also examined their long-term engagement in transnational economic activities according to employment status, gender and legal status. The data analysis yielded the following key findings.

First, the pattern of migrants’ educational levels varies significantly across origin countries. This is reflected in employment profiles, with Congolese and Ghanaian migrants being more often employed in higher-skilled occupations than are Senegalese migrants. A strong self-selection effect appears for specific destination countries. While migration to ‘traditional’ destinations – that is France, Belgium and the UK – involved much higher proportions of students and medium- to high-skilled workers, flows to ‘new’ migrant–receiving countries, such as Italy and Spain for Senegalese, the UK for Congolese and the Netherlands for Ghanaians were found to be mainly composed of less educated and lower-skilled individuals.

Besides structural factors that made former colonial countries more attractive to the migrants from their old colonies (such as a shared language, a common educational system, specific opportunities offered to students, etc.), historical, economic, political and cultural relationships with the elites of the former colonies have been maintained. As a result, there has been a social class stratification according to destination country, forming a complex relational capital, which translates in a framework of opportunities for the social and cultural elites from origin countries.

While most experts acknowledge the fact that well-educated individuals from Africa are more likely to move to their former colonial power (Constant and Tien 2009), very few studies have examined the force of colonialism as a determinant of African migration to Europe. Analysis from this research provides quantitative evidence of migration self-selection based on work experience and educational level, suggesting that the destination choice of the more highly educated has been strongly affected – at least until recently – by colonial legacies, with opportunities in the former colonial countries exerting a long-lasting pull on the highly skilled and students.

However, migration patterns are changing fast. The old receiving countries are receiving new flows, both in terms of countries of origin (e.g. the Congolese in the UK who, as we have seen, show different outcomes to those of Ghanaians in the same country), and in terms of changes in the socio-economic composition of the flows from the former colonies. In addition, the ability of labour markets to absorb and integrate a foreign labour force changes over time, as do the conditions of entry, admission and access to the labour market for different migrant groups (unskilled, skilled, students, asylum seekers, women, etc.) (Cangiano 2012). The economic downturn in European countries in the last few years has strongly affected migrant workers’ participation in the labour market, severely challenging their economic integration at destination. Migrants’ economic performances therefore need to be constantly monitored over time for different groups and different countries.

Second, the analysis shows that a high proportion of Africans experience downgrading (employment in jobs for which they are overqualified) on entering the European labour market. Newly arrived migrants are more likely to take jobs below their formal educational level as they often do not have host-country-specific human capital (i.e. knowledge of the receiving country’s language and the way its labour market functions), or have the same access to functional networks as more established migrants do (OECD 2012). The literature stresses that in time they would tend to move on from such jobs as they become more integrated into the host country’s labour market. However, our data suggest that over-qualification may or may not decrease over time, depending on origin country (and related migration system) and destination country.

The analysis of education-occupation mismatch among skilled workers, which is seldom studied from a longitudinal perspective, shows that it already affects candidates to migration in their origin countries. Its incidence increases dramatically upon entry in the host country, falls to around 50% by the sixth year of stay abroad and, for the Senegalese and Ghanaians, after 10 year of stay reaches a level similar to the one prior to migration, while the Congolese in Europe more often remain stuck in jobs for which they are overqualified. This result suggests that, overall, migration does not pay off for well-educated Africans, who are subjected to extended periods of de-skilling on arrival and have limited opportunities to ameliorate their occupational situation over time.

While the overall share of migrants working in skilled jobs seem to increase over time, this is only partly the result of a ‘catch up’ in their careers by workers overqualified for the jobs they held on entry, or of upward occupational mobility more broadly. Rather it reflects the entry into the labour market of those who have completed their studies in the destination countries.

Thus things seem to go better for African students in Europe. This finding suggests that pursuing education and training in destination countries is more likely to yield positive labour market outcomes than trying to access medium- or high-skill jobs on arrival in the destination countries, with the exception of skilled Ghanaian in the UK, who integrate more easily. Foreign students in Europe seem more likely to overcome the labour market problems that other immigrants face immediately upon arrival as they are in a better position to acquire destination-country-specific language skills, training, experience and more mixed social networks, which the literature suggests is more valuable than education acquired in the country of origin (Friedberg 2000). In addition, local employers can assess and understand their credentials better than credentials earned in the origin country (Hawthorne 2008).

However, although European countries are increasingly introducing policies to attract highly qualified migrants, this does not necessarily mean that international students mobility is a skilled-migration panacea. International students are likely to stay and work in the host country once they have completed their studies (Rosenzweig 2008), but their flows are volatile, as students are a highly mobile population. There is growing competition between developed countries for international students and international students may also decide to come back to their origin countries once they have completed their studies abroad. Finally, some doubts have recently been cast on former students’ perceived ‘work readiness’ in the host country (Hawthorne 2008) and on their successful integration in the labour markets in the countries where they have completed their studies.

Overall, the most successful example of labour market integration from MAFE research comes from Ghanaian migration to the UK, where a majority of migrants who had been in the country for over a decade were found to be working in skilled positions. By contrast, Ghanaian migrants in the Netherlands were found to be mainly working in unskilled positions, with the proportion of those employed in unskilled jobs increasing over time. The comparison between Ghanaians in the UK and the Netherlands suggests that conditions are more favourable in the UK in terms of labour market integration, but it also reflects selection, in that the Ghanaian migrant flows arriving in the two countries differ in their educational and occupational composition. Comparison between Ghanaian and Congolese migrant outcomes in the UK belies the idea that the UK is the optimum for the integration of migrants into the labour market. Despite having fairly high levels of education, Congolese in the UK show much lower labour market outcomes than the Ghanaians there. Language barriers and lack of recognition of diplomas may hamper their integration into the labour market, as may the fact that a large proportion of Congolese migrants arrived as asylum seekers (see Chaps. 8 and 11), a category that has been shown to commonly experience disadvantage in accessing qualified jobs in Europe (Cangiano 2012). Further analysis is needed to disentangle the effect of context (UK as an optimum in integrating labour migrants) from the effect of composition (the specific features of the population concerned).

Fourth, evidence provided in this chapter suggests that labour market participation in destination countries is strongly affected by gender and is primarily connected to migrants’ departure conditions and motivations. While few men were unemployed before leaving home, women are much more likely to have been excluded from the labour market in their origin countries (especially among the Senegalese and Congolese). Women’s inactivity rates rise upon arrival, with different subsequent outcomes for each of the three origin-country groups. However, a much higher proportion of women migrants remain inactive at later stages of their time in Europe and they are more likely to return to inactivity having joined the labour market at some point.

Fifth, the chapter showed that the data do not unequivocally confirm the common image of return migration as a “triple win situation” for the individual migrant, the destination country and the origin country. Among the Senegalese and Congolese, return migrants seem to regain a status similar to the one they had before leaving their country of origin, showing a brain ‘regain’, rather than a ‘brain gain’. While return migrants in all three countries are better placed than non-migrants, most of this difference seems to have already existed before they migrated.

Ghanaian returnees show a more dramatic increase in skilled positions upon their return. This group are coming back mainly from the UK, where labour market attainments were comparatively good, and their good economic outcomes back home suggest a positive link between economic integration at destination and reintegration in the home country economy.

This suggests that return should also be studied as a reverse migration process, involving new and specific challenges for (re)integration into the local labour market, but in connection with the earlier trajectory before migrating and during the time abroad. Labour market integration in receiving countries, in terms of labour status, skill level and activity sector, largely determine whether or not the acquired skills and competences can be useful for economic reintegration in origin country labour markets (Ferro 2010). A migrant who worked as an unskilled labourer in the manufacturing sector in Europe will not necessarily find a demand (especially in rural areas) for the skills they acquired abroad. Nor do jobs held in Europe, in a highly segmented labour market, necessarily give migrants the kind of industrial culture that can be translated into organizational capacity and ability to invest in productive activities upon return (ibid.).

Finally, the chapter analysed migrants’ transnational activities while abroad, which may range from occasional contributions to the origin household to long-term commitment to productive and social investments in the home locality. Decisions about private investments in assets at origin, remittance transfers and contributions to local or migrant associations depend on migrants’ occupational and economic trajectories and are also connected with eventual return and reintegration into the home country.

As is consistent with a progressive integration into the labour market at destination, levels of all the three types of activity recorded by the MAFE survey increase between the time of arrival in Europe and the time of the survey, for Congolese, Ghanaian and Senegalese migrants alike. Sending money regularly to the origin household is the most common practice, regardless of the migrant’s gender and their employment and legal status. The lack of security for persons and businesses in DR Congo may explain the relatively low level of economic contributions by Congolese migrants, especially with regard to investment in assets and participation in associations. Ghanaians tend to invest more and to participate more in migrant associations than the Congolese or the Senegalese even on arrival in Europe. Senegalese migrants, both men and women, show the highest proportion of remittance senders at all times.

Looking at these transnational flows and activities from the standpoint of reciprocal relations between countries and connecting them with the migrants’ labour trajectories at origin and destination provides a better picture of the potential impact of migration on origin households and on the African survey countries.

The connection between migration and development is at the centre of a long-lasting debate on the possible positive impact of migrants as ‘development agents’ both during their stay abroad and after their return (de Haas 2012; Geiger and Pécoud 2013). Analysis of migrants’ transnational engagement and potential social and economic re-integration upon return is crucial, insofar as economic contributions and return are very much dependent upon the success of the migration experience – or the lack of it (Castagnone 2011). As failure to integrate into the labour market at destination may prevent migrants from achieving the hoped-for level of economic contribution at origin, migrants who return after failing to integrate at destination may decide to migrate anew (Sinatti 2010).

From this standpoint, longitudinal and transnational approaches prove to be indispensable for analysing migrants’ economic trajectories at different stages and across different countries as interconnected pieces of a broader puzzle.

References

Ammassari, S. (2004). From nation building to entrepreneurship: The impact of elite return migrants in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Population, Place and Space, 10, 2.

Beine, M., Romain, N., & Lionel, R. (2013). The determinants of international mobility of students (CEPII, working paper n. 30).

Black, R., Fielding, T., King, R., Skeldon, R., & Tiemoko, R.. (2003). Longitudinal studies: An insight into current studies and the social and economic outcomes for migrants (Sussex Migration Working Paper 14). Falmer: University of Sussex.

Black, R., & King, R. (2004). Editorial introduction: Migration, return and development in West Africa. Population, Place and Space, 10(2), 75–84.

Borjas, G. J. (1999). The economic analysis of immigration. In O. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3A, pp. 1697–1760). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Cangiano, A. (2012). Immigration policy and migrant labour market outcomes in the European Union: New evidence from the EU Labour Force Survey, (FIERI working paper). http://www.labmiggov.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Cangiano-Lab-Mig-Gov-Final-Report-WP4.pdf

Cassarino, J. P. (2004). theorising return migration: The conceptual approach to return migrants revisited. International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 6(2), 253–279.

Castagnone, E. (2011). Building a comprehensive framework of African mobility patterns: The case of migration between Senegal and Europe. PhD Thesis, Graduate School in Social, Economic and Political Sciences, Department of Social And Political Studies, University of Milan.

Constant, A. F., & Tien, B. N. (2009). Brainy Africans to Fortress Europe: For money or colonial vestiges? (IZA DP No. 4615). http://ftp.iza.org/dp4615.pdf

de Haas, H. (2012). The migration and development pendulum: A critical view on research and policy. International Migration 50(3), 8–25. See more at: http://www.imi.ox.ac.uk/people/hein-de-haas#sthash.cXmQAqT2.dpuf

de Haas, H. (2008). Migration and development: A theoretical perspective (IMI Working Paper 9). Oxford: International Migration Institute, University of Oxford.

de Haas, H., & Fokkema, T. (2011). The effects of integration and transnational ties on international return migration intensions. Demographic Research, 25(24), 755–782.

Duleep, H. O., & Dowhan, D. J. (2008). Research on Immigrant Earnings. Social Security Bulletin, 68, 31–50.

Dustmann, C., & Frattini, T., (2010, November 19). Can a framework for the economic cost-benefit analysis of various immigration policies be developed to inform decision making and, if so, what data are required?.

Fall, P. D. (2010). Sénégal. Migration, marché du travail et développement, ILO. http://www.ilo.org/public/french/bureau/inst/download/senegal.pdf

Ferro, A. (2010). Migrazione, ritorni e politiche di supporto. Analisi del fenomenodellamigrazione di ritorno e rassegna di programmi di sostegno al rientro (Working Paper CeSPI n. 14). http://www.cespi.it/AFRICA-4FON/WP%2014%20Ferro-ritorni.pdf

Friedberg, R. M. (2000). You can’t take it with you? Immigrant assimilation and the portability of human capital. Journal of Labor Economics, 18(2), 221–251.

Geiger, M., & Pécoud, A. (2013). Migration, development, and the “Migration and development nexus”. Population, Space and Place, 19(4), 369–374.

Ghosh, B. (Ed.). (2000). Managing migration: Time for a New International Migration Regime? Oxford: OUP.

Hawthorne, L. (2008). The growing global demand for students as skilled migrants. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Kabbanji, K. (2013). Towards a global agenda on migration and development? Evidence from Senegal. Population, Space and Place, 19(4), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1782.

King, R., Thomson, M., Fielding, T., & Warnes, T. (2006). Time, generations and gender in migration and settlement. In Penninx (Ed.), The dynamics of migration and settlement in Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Kohnert, D. (2007). African migration to Europe: Obscured responsibilities and common misconceptions (GIGA Working Paper No 49).

Lubotsky, D. (2007). Chutes or ladders? A longitudinal analysis of immigrant earnings. Journal of Political Economy, 115, 820–867.

Massey, D. S. (1987, Winter). The ethnosurvey in theory and practice. International Migration Review, 21(4), Special Issue: Measuring international migration: Theory and practice (pp. 1498–1522).

Mezger, C., & Flahaux, M.-L. (2010). Returning to Dakar: The role of migration experience for professional reinsertion (MAFE Working Paper 8). http://www.ined.fr/fichier/ttelechargement/41829/telechargementfichierfrwp8mezger.flahaux2010.pdf

Münz, R. (2008). Migration, labor markets, and integration of migrants: An overview for Europe (SP Discussion Paper No. 0807. Social Protection Discussion Paper Series). World Bank.

Münz, R. (2007). Migration, labor markets, and integration of migrants: An overview for Europe. Hamburg: HWWI.

OECD. (2007). Jobs for immigrants (Vol. 1). Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2012). Settling In: OECD Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2012, OECD, 2012.

Piper, N. (2009). Guest editorial. The complex interconnections of the migration–development nexus: A social perspective. Population, Space and Place, 15, 93–101.

Piracha et al. (2012). Immigrant over- and under-education: The role of home country labour marketexperience. IZA Journal of Migration.

Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2006). Immigrant America: A portrait (3rd ed., revised, expanded and updated). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Quintini, G. (2011). Over-qualified or under-skilled: A review of existing literature (OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 121). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5kg58j9d7b6d-en

Rosenzweig, M. (2008). Higher education and international migration in Asia: Brain circulation. In Annual World Bank conference on development economics, pp. 59–100.

Shima, I., (2010). Return migration and labour market outcomes of the returnees: Does the return really pay off? The case-study of Romania and Bulgaria, Research Centre for International Economics (FIW), FIW Research Reports, 10(7).

Sinatti, G. (2010). ‘Mobile Transmigrants’ or ‘Unsettled Returnees’? Myth of Return and Permanent Resettlement among Senegalese Migrants. Population Space and Place, special issue ‘Onward and Ongoing Migration’.

Sakho, P. (2013). New patterns of migration between Senegal and Europe (France, Italy and Spain) (MAFE Working Paper n°21). Paris, INED

Sjenitzer, T., & Tiemoko, R. (2003). Do developing countries benefit from migration? A study of the acquisition and usefulness of human capital for Ghanaian Return Migrants. Sussex Centre for Migration Research.

Toma, S., & Vause, S.. (2011). S. Migrant networks and gender in Congolese and Senegalese international migration (MAFE Working Paper Series. No. 13). Paris: Migrations between Africa and Europe, INED.

Van Hear, N., & Nyberg Sørensen, N. (Eds.). (2003). The migration-development nexus (pp. 159–187). Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Wimmer, A., & Glick Schiller, N. (2003). Methodological nationalism and the study of migration. Archives Européennes de Sociologie, 53(2), 217–240.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Castagnone, E., Schoumaker, B., Nazio, T., Bartolini, L. (2018). Understanding Afro-European Economic Integration Between Origin and Destination Countries. In: Beauchemin, C. (eds) Migration between Africa and Europe. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69569-3_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69569-3_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-69568-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-69569-3

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)