Abstract

Majority of neonatal deaths occur in developing countries. There is an increase in the proportion of neonatal deaths as part of the under-5 mortality over the past decade. Hence we need to accelerate further to achieve the goal of single digit neonatal mortality rate (NMR) by 2030. The two major arms of NMR reduction include facility-based neonatal care (FBNC) and home-based neonatal care (HBNC). FBNC addresses care at birth, care of the normal newborn, and care of small and sick newborns. HBNC provides continuum of care for newborn and post-natal mothers facilitated by Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers. One of the main challenges is to maintain good quality of neonatal care. Zero separation, linkage of community & facility and roles of professional bodies are considered way forward to achieve India Newborn Action Plan (INAP) goals. This review summarizes existing programs for newborn health and diseases and provides an over-arching view of the way-forward.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The world saw an estimated 2.3 million newborn babies die in 2021. The proportion of neonatal deaths as a share of under-5 deaths has increased from 41% in 2000 to 46% in 2021. Approximately 80% of these, are low birth weight (LBW) neonates and two-thirds are born prematurely [1]. Though India is still the major contributor to these deaths, however; a significant reduction over two decades in neonatal mortality rate in India from 44.7 (42.2-47.3) per 1000 live births in 2000 to 19.1 (17.1-21.4) per 1000 live births in 2021 [2] has been observed. The major causes of newborn deaths in India are elucidated in Fig. 1.

The survival of a child cannot be addressed in isolation, since it is closely tied to the mother's health. All national programs adhere to the continuum of care idea, which focuses care during crucial life stages to improve child survival. The provision of newborn care at several levels of health facilities – facility-based newborn care (FBNC) and essential services at home, through community outreach – home-based newborn care (HBNC) are two strategic pillars on which newborn care is built in India (Fig. 2). Increased coverage of FBNC and improved HBNC have put India on the road to achieve India Newborn Action Plan (INAP) targets [6]. This manuscript aims to summarise the major contributors to decline in neonatal mortality in India and analyse the challenges and way forward.

Newborn care at different levels [3,4,5]. CPAP Continuous positive airway pressure, JSSK Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram, KMC Kangaroo mother care, LaQshya Labor room & quality improvement initiative, NSSK Navajaat Shishu Suraksha Karyakram, ROP Retinopathy of prematurity, SNCU Special newborn care unit

India Newborn Action Plan

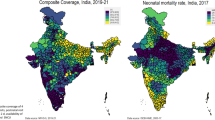

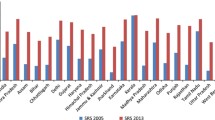

The World Health Organization launched a venture in 2014 known as "Every newborn action plan (ENAP)” which was in alignment with the global strategy for Women & Children's health to focus on the quality of care at birth which would save millions of lives [7]. The action plan was launched with a vision to end all preventable neonatal deaths and ensure that infants and children survive and thrive and grow up to achieve their maximum potential [8]. India has adapted ENAP to INAP with the goal to attain a single-digit neonatal mortality rate by 2030 by ending all preventable neonatal deaths and individual states to achieve this target by 2035 [9]. Under the 6 pillars listed in INAP, programs have been conceived and successfully implemented (Table 1). Through INAP it was found that 83% of the districts in India have at least one Special newborn care unit (SNCU). Neonatal mortality was reduced by 60% from 1990 (57 /1000 live births to 33) and a 30% reduction from 2010 to 2018 (33 /1000 live births to 23). Currently, India has achieved three of the four ENAP coverage targets for 2025 i.e., 80% coverage of skilled birth attendant (SBA) at delivery, >60% coverage for postnatal care within 2 d for mother and baby, and >80% SNCU coverage [6].

In India, the newborn health initiatives received emphasis in the year 2005 under the Reproductive maternal newborn child & adolescent health (RMNCH+A) program under the National Health Mission (NHM) and included several programs aimed at improving newborn care (Table 2) [11] . Care for the newborn was envisaged at various levels under the facility-based newborn care program.

Facility-Based Newborn Care

The Lancet survival series has estimated that health-facility based interventions can reduce neonatal mortality by as much as 23-50% [12]. Facility-based newborn care (FBNC services at different levels of healthcare facilities) is one of the key strategies adopted by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India (MoHFW, GoI) under the NHM and Reproductive Child Health II (RCH II) to improve the status of newborn health in the country. While, WHO classifies the three levels of newborn care as Essential Newborn care (Primary), Special newborn care (Secondary), and Intensive care (Tertiary). FBNC addresses care at birth, care of the normal newborn, and care of small and sick newborns (Table 3).

Essential Newborn Care

Care at birth, breastfeeding support, prevention of hypothermia, and infections, identification of problems including birth defects and prompt referral, and discharge counseling are the key aspects of ENC addressed by the new Navjat Shishu Suraksha Karyakram [3]. In 2022, WHO published new recommendations for the normal newborn [13] & newborn screening for hearing impairment, hyperbilirubinemia, and eye abnormalities have been introduced.

Special Newborn Care

Small and sick newborns need inpatient care (24/7) in a facility with a focus on the provision of warmth, feeding and breathing support, prevention and treatment of infection, and detection and management of birth defects and complications such as hypoglycemia, jaundice, anemia, apnea, necrotizing enterocolitis, neonatal encephalopathy and seizures [14]. Kangaroo mother care (KMC) and continuous positive airway pressure are key aspects of care for a small newborn.

Intensive Newborn Care

Some very small and sick newborns need mechanical ventilation, surfactant therapy, parenteral nutrition, surgical and genetic services which are provided in intensive care units.

Essential newborn care is provided at all levels of facilities in the Newborn care corner (NBCC) and sick newborn care is provided in the Newborn stabilization units (NBSU) and the SNCU. Intensive care is provided in the Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), usually attached to medical colleges. Under the FBNC program, SNCUs have been established at any health facility where the delivery load is more than 3000 per year i.e., at most district hospitals and some of the sub-district hospitals and includes all care for small and sick newborns including continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) except for assisted ventilation and major surgeries.

Since its inception in 2003, SNCUs have been the pillar of FBNC and >900 SNCUs have been established covering >83% of the districts in India [15]. Emphasizing the importance of breastfeeding to reduce neonatal mortality rate (NMR), MoHFW has set up comprehensive lactation management centers (CLMC) at medical colleges, high-load districts, and lactation management units (LMU) at district hospitals. and lactation support units (LSU) at delivery points [16]. The breast milk bank at CLMC supports the small and sick newborns admitted to the SNCUs. As of FY 2020-2021, 15 CLMCs and 3 LMUs are established in seven states. The SNCU also provides post-discharge follow up and babies identified with problems are referred to the District Early Intervention Center (DEIC) under the Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK). MoHFW has developed an "Operational Guide” [14] not only for providing care but also for record keeping and monitoring. UNICEF supported the NHM to develop a real-time monitoring system – “SNCU online” - to assess SNCU performance and track newborns post-discharge. More than 90% of facilities are reporting online. This system records vital information related to antenatal care and care in the labour room, SNCU care and post-discharge follow-up care. It aids in the rapid review of the performance of each SNCU and for benchmarking [15].

The FBNC model of care in India is based on the principle of regionalized care with an appropriate referral systems which has shown to reduce NMR [4]. It also resulted in more very low birth weight (VLBW) neonates being transferred to the higher center. Linkages between the higher and lower facilities, mechanisms for in-utero transfer of high-risk pregnancies, and safe transfers of newborns are essential for optimal use of resources.

Referral services and transport are integral to regionalized care and influence NMR. Free ambulance service is now available in almost all parts of the country to facilitate referral under NHM & state initiatives [17, 18]. However, only a few are geared for transport of sick neonates in terms of personnel and quality of care. In a study from North India, 40% of the referred neonates were not accompanied by health personnel, only 15% had a complete referral note, and two-thirds were hemodynamically stable at arrival; these had a significant effect on the outcome. In Tamil Nadu, government partnership with GVK Emergency Management and Research Institute (GVK EMRI) has ensured that 80% of the babies reach the facility in stable clinical condition resulting in 94% survival of transported infants [19].

The FBNC model has contributed significantly to a reduction in NMR to 19 per 1000 live births in 2021. A review of the effectiveness of FBNC on neonatal outcomes found that high patient volume (>2,000 deliveries/ year), inborn status, availability of referral system and inter-facility transfers, and adequate nursing care staff in neonatal units demonstrated protective effect in reducing neonatal mortality rates [17, 20, 21]. Neonatal mortality is higher in the SNCUs than in the NBSU due to high referral and the pattern in the SNCUs is higher among LBW and preterm babies, emphasizing the need to strengthen care for these small babies [22]. Neonatal jaundice is one of the most common causes of admission in SNCUs [23, 24] resulting in overcrowding.

There is however an urgent need to bring in the culture of quality & safety in neonatal care. It is estimated that 60% of the one million newborn deaths are due to poor quality of care [21]. While in districts with high quality of care, institutional deliveries reduce NMR by about 8 /1000 live births, the NMR in institutional deliveries at the lowest quintile of quality of care is higher [25].

Home-Based Newborn Care (HBNC)

Home-based newborn care (HBNC) is a strategy implemented by government of India to overcome the burden of newborn mortality in the first week of life. It provides continuum of care for newborn and post-natal mothers. HBNC introduced since 2011 is centred around Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) and it is the main community-based approach to newborn health [5]. The ASHAs visit the mother-baby dyad six times in the first 6 wk to provide advice on newborn care practices, breastfeeding support, keeping warm, KMC and identification of illness, and administration of antibiotics where referral is not possible. Under this scheme, funds are allocated for training of ASHAs, supportive supervision by ASHA facilitators, incentive to ASHAs for home visits and purchase of HBNC kits. ASHAs are paid an incentive of Rs. 250 for visiting each newborn. The HBNC is feasible and effective in various settings [26].

The Gadchiroli trial in tribal Maharashtra has been the basis for HBNC [27], where it has sustained for >23 y with decreasing mortality [28]. The HBNC model has been evaluated in a cluster randomized trial by ICMR-HBMYI study group and found to be effective in reducing neonatal and infant mortality even in setting with high rates of facility births [29]. Implementation research initiatives [30, 31] have shown that high-impact interventions such as KMC, and home treatment of neonatal sepsis can be scaled up through the HBNC model with additional training and supportive supervision of ASHAs [32]. Establishing linkages between the facility and the ASHAs is crucial to provide a continuum of care. Similarly, a study done by Pathak et al., 2021 in Uttar Pradesh, has found that majority of newborns got all the age-appropriate home visit [33]. The Home-based Newborn Care Programme is being implemented under National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in all States and UTs except for Himachal Pradesh, Goa, Kerala, Chandigarh, Daman & Diu, and Puducherry [34].

The SNCU Plus initiative aims at facilitating contact with babies discharged from SNCUs. A recent review of the program found that among those followed up, the coverage of all three visits was 97% and the mortality till 6 wk was 1.5%; although it was higher among LBW babies (2.02%), highlighting that follow-up at critical time points can improve survival of small and sick newborns discharged from SNCUs. As per State Report, during FY 2020-21, more than 1.33 Crore newborns were visited by ASHAs under the HBNC program [35].

Way Forward – Actionable Recommendations

We need to act now to strengthen facility and home based newborn care if we are to attain the INAP targets. Table 4 provides some actionable recommendations to further reduce the three major causes of neonatal mortality. The recent Lancet series on the “small vulnerable newborn” [36] has highlighted the need to integrate stillbirths to burden assessment and to implement 10 proven interventions [37] to achieve global targets in preventing neonatal mortality. Implementation research [38] to understand “how to” rapidly scale-up proven interventions nationally to achieve global targets is the need of the hour.

With a focus on small and sick newborn care [39] , there is a need to strengthen health systems to provide high-quality FBNC. Though zero-separation of the mother-baby dyad is recommended [13], separation of the LBW is the norm (39.5% to 51.4%) [40]. The recent iKMC trial [41] has shown that zero separation for the unstable LBW is not only feasible but can reduce newborn mortality by an additional 25%, introducing the concept of M-NICU (Mother-Newborn Intensive Care Unit), a paradigm shift in how small infants are cared for. There is a need to implement and scale up the new WHO recommendations for the normal newborn [13] and preterm and low birth weight with inclusion of family participatory care [39].

While India has made great strides in establishing SNCUs in every district, there are challenges in implementation and quality of care [42]. There is wide variation in the quality of maternity and neonatal care across facilities with scope for improvement both in the public and private sectors [43, 44]. Interventions to improve intrapartum care contribute to the maximum reduction in neonatal mortality. Dakshata [45] skill training and LaQshya, launched in 2017 aim to strengthen key processes related to delivery care in public health facilities [10]. "SUMAN – Surakshit Matritva Aashwasan” launched in 2019 aims to provide respectful and quality healthcare to every woman and newborn visiting the public health facilities. In 2021, MoHFW launched the MusQan initiative to ensure quality child-friendly facility-based services. This initiative ensures the provision of quality child-friendly facility-based services (SNCU, NBSUs, Pediatric Wards/ HDUs/ ICUs) in public health facilities to children from birth up to 12 y of age. It has also shown promising steps towards strengthening facility based newborn care with aims to reduce preventable newborn and child morbidity and mortality.

A training package to improve knowledge and clinical skills using point of care quality improvement (POCQI) has been shown to improve neonatal outcomes [46]. Onsite mentoring improves neonatal outcomes [47] and hub and spoke model with the medical colleges serving as hubs have been proposed [48]. With the routine data collected by SNCU online, a composite index that serves as a proxy marker of quality of clinical service – the SNCU Quality of Care Index- SCQI tool has been developed [49]. The SCQI implementation has helped identify bottlenecks and address quality concerns by the district and facility teams [50].

India has taken steps to strengthen primary healthcare through health and wellness centres [51] under Ayushman Bharat program [52]. This is a great opportunity to revive and fully integrate and address challenges and bottlenecks in delivery of newborn and maternal health interventions. The community process and platforms which have been created in last two decades [53] should also be optimally utilised.

Professional bodies like National Neonatology Forum and Indian Academy of Pediatrics have focused on developing and implementing training packages like Navjaat Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (NSSK), neonatal resuscitation, and preterm care using novel mobile-based e-learning [54]. The Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India (FOGSI) offers a quality improvement and certification initiative called “Manyata” for the private sector.

Conclusions

Continuum of care starting from the antenatal period, FBNC, and continued support in the community by HBNC has achieved moderate to high coverages. Implementation research to accelerate coverage of key interventions, zero separation of the mother-baby dyad, and focus on the quality of care are the ways forward to achieve INAP targets set for 2030.

References

Survive and Thrive. Transforming Care for Every Small and Sick Newborn. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241515887. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

UN-IGME-Child-Mortality-Report. 2022. Available at: https://childmortality.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/UN-IGME-Child-Mortality-Report-2022.pdf. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

NSSK Resource Manual: National Health Mission. Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=1&sublinkid=1427&lid=781. Accessed on 9 May 2023.

Facility Based Newborn Care (FBNC): National Health Mission. Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/index4.php?lang=1&level=0&linkid=484&lid=754. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

Home Based Care of New Born and Young Child. Available at: https://hbnchbyc. mohfw.gov.in/AboutUs/aboutHBNC. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

INAP-progress_card_2020. Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/INAP-progress_card_2020.pdf. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

World Health Organization. Every newborn: an action plan to end preventable deaths. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/127938. Accessed on 9 May 2023.

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, et al. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet. 2014;384:347–70.

Child Health Division MOHFW, INAP_final. Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/inap-final.pdf. Accessed on 9 May 2023.

LaQshya-Guidelines.pdf. Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/RMNCH_MH_Guidelines/LaQshya-Guidelines.pdf. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

NHM, MOHFW, RMNCH+A:National Health Mission . Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=1&sublinkid=794&lid=168. Accessed on 9 May 2023.

Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, et al. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005;365:977–88.

WHO Recommendations On Maternal And Newborn Care For A Positive Postnatal Experience. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240045989. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

Operational-Guide-(FBNC). Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/CH-Programmes/FBNC/Operational-Guide-(FBNC). Accessed on 28 May 2023.

Child Health Division, MOHFW, Operational Status of SNCU in India- Technical Report. Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/child-health/annual-report/sncu_technical_report_jan-march_2011.pdf. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

National_Guidelines_Lactation_Management_Centres in Public Health Facilities. Available at:https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/IYCF/National_Guidelines_Lactation_Management_Centres.pdf. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

Mishra N, Saini SS, Jayashree M, Kumar P. Quality of referral, admission status, and outcome of neonates referred to pediatric emergency of a tertiary care institution in north India. Indian J Community Med. 2022;47:253–7.

Admin YK, Nagu Magu Ambulance Service Yuva Kanaja. 2022. Available at: https://yuvakanaja.in/en/healthfamily-welfare-dept-en/nagu-magu-ambulance-service/. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

Kumutha J, Rao GVR, Sridhar BN, Vidyasagar D. The GVK EMRI maternal and neonatal transport system in India: a mega plan for a mammoth problem. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;20:326–34.

Neogi SB, Malhotra S, Zodpey S, Mohan P. Does facility based newborn care improve neonatal outcomes? A review of evidence. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:651–8.

Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, Danaei G, García-Saisó S, Salomon JA. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet. 2018;392:2203–12.

Kshirsagar VD, Rajderkar SS. An assessment of admission pattern and treatment outcomes of neonates admitted in centers under facility-based newborn care program in Maharashtra, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11:3455–8.

Child Health Division. MOHFW. Two Year Progress of SNCUs-A Brief Report_(2011-12_&_2012-13).pdf. Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/child-health/annual-report/Two_Year_Progress_of_SNCUs-A_Brief_Report_(2011-12_&_2012-13).pdf. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

NHSRC, Monitoring Report: Karnataka. 2013;55. Available at: http://164.100.117.80/sites/default/files/Karnataka%20Monitoring%20Report%20-%20Q1%202013-14.pdf . Accessed on 28 May 2023.

Lee H-Y, Leslie HH, Oh J, et al. The association between institutional delivery and neonatal mortality based on the quality of maternal and newborn health system in India. Sci Rep. 2022;12:6220.

Garg S, Dewangan M, Krishnendu C, Patel K. Coverage of home-based newborn care and screening by ASHA community health workers: findings from a household survey in Chhattisgarh state of India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11:6356–62.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, Reddy MH, Deshmukh MD. Effect of home-based neonatal care and management of sepsis on neonatal mortality: field trial in rural India. Lancet. 1999;354:1955–61.

Bang A, Baitule S, Deshmukh M, Bang A, Duby J. Home-based management of neonatal sepsis: 23 years of sustained implementation and effectiveness in rural Gadchiroli, India, 1996–2019. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:e008469.

Rasaily R, Saxena NC, Pandey S, et al. Effect of home-based newborn care on neonatal and infant mortality: a cluster randomised trial in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e000680.

Mony PK, Tadele H, Gobezayehu AG, et al. Scaling up Kangaroo mother care in Ethiopia and India: a multi-site implementation research study. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6:e005905.

Mukhopadhyay R, Arora NK, Sharma PK, et al. Lessons from implementation research on community management of possible serious bacterial infection (PSBI) in young infants (0–59 days), when the referral is not feasible in Palwal district of Haryana, India. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0252700.

Jayanna K, Rao S, Kar A, et al. Accelerated scale-up of Kangaroo Mother Care: evidence and experience from an implementation-research initiative in south India. Acta Paediatr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.16236.

Pathak PK, Singh JV, Agarwal M, Singh VK, Tripathi SK. Study to assess the home-based newborn care (HBNC) visit in rural area of Lucknow: a cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:1673–7.

Hannah E, Dumka N, Ahmed T, Bhagat DK, Kotwal A. Home-based newborn care (HBNC) under the national health mission in urban India – A cross country secondary analysis. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2022;11:4505.

Annual Report 2018-19 | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare | GOI. Available at: https://main.mohfw.gov.in/basicpage/annual-report-2018-19. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

Lawn JE, Ohuma EO, Bradley E, et al. Small babies, big risks: global estimates of prevalence and mortality for vulnerable newborns to accelerate change and improve counting. Lancet. 2023;401:1707–19.

Hofmeyr GJ, Black RE, Rogozińska E, et al. Evidence-based antenatal interventions to reduce the incidence of small vulnerable newborns and their associated poor outcomes. Lancet. 2023;401:1733–44.

Theobald S, Brandes N, Gyapong M, et al. Implementation research: new imperatives and opportunities in global health. Lancet. 2018;392:2214–28.

Standards for Improving the Quality of Care for Small and Sick Newborns in Health Facilities. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240010765. Accessed on 28 May 2023.

Semrau KEA, Mokhtar RR, Manji K, et al. Facility-based care for moderately low birthweight infants in India, Malawi, and Tanzania. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3:e0001789.

Immediate “Kangaroo Mother Care” and Survival of Infants with Low Birth Weight. New Engl J Med. 2021;384:2028–38.

Neogi SB, Khanna R, Chauhan M, et al. Inpatient care of small and sick newborns in healthcare facilities. J Perinatol. 2016;36:18–23.

Hanson C, Singh S, Zamboni K, et al. Care practices and neonatal survival in 52 neonatal intensive care units in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, India: a cross-sectional study. PLOS Med. 2019;16:e1002860.

Tripathi S, Srivastava A, Memon P, et al. Quality of maternity care provided by private sector healthcare facilities in three states of India: a situational analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:971.

Jain Y, Chaudhary T, Joshi CS, et al. Improving quality of intrapartum and immediate postpartum care in public facilities: experiences and lessons learned from Rajasthan state, India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:586.

Deorari AK, Kumar P, Chawla D, et al. Improving the quality of health care in special neonatal care units of India: a before and after intervention study. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2022;10:e2200085.

Prashantha YN, Shashidhar A, Balasunder BC, Kumar BP, Rao PNS. Onsite mentoring of special newborn care unit to improve the quality of newborn care. Indian J Public Health. 2019;63:357–61.

Srivastava S, Datta V, Garde R, et al. Development of a hub and spoke model for quality improvement in rural and urban healthcare settings in India: a pilot study. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9:e000908.

Kumar H, Khanna R, Alwadhi V, et al. Catalytic support for improving clinical care in special newborn care units (SNCU) through composite SNCU quality of care index (SQCI). Indian Pediatr. 2021;58:338–44.

Saboth Md PK, Sarin PhD E, Alwadhi Md V, et al. Addressing quality of care in pediatric units using a digital tool: implementation experience from 18 SNCU of India. J Trop Pediatr. 2021;67:fmab005.

Lahariya C. Health & wellness centers to strengthen primary health care in India: concept, progress and ways forward. Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87:916–29.

Lahariya C. Ayushman Bharat” program and universal health coverage in India. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55:495–506.

Lahariya C, Roy B, Shukla A, et al. Community action for health in India: evolution, lessons learnt and ways forward to achieve universal health coverage. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2020;9:82–91.

Anand P, Thukral A, Deorari AK, National Neonatology Forum Network. Dissemination of best practices in preterm care through a novel mobile phone-based interactive e-learning platform. Indian J Pediatr. 2021;88:1068–74.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Chandrakant Lahariya and Data and Evidence Team at the Foundation for People-centric Health Systems, New Delhi for providing technical comments and inputs on earlier version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SRPN conceived the flow of manuscript, wrote part of the first draft and reviewed it. BB performed literature search and wrote part of the first draft. Both the authors approve the final manuscript submitted. SRPN will act as guarantor for this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

PN, S.R., Balachander, B. Care of Healthy as well as Sick Newborns in India: A Narrative Review. Indian J Pediatr 90 (Suppl 1), 29–36 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-023-04752-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-023-04752-0