Abstract

Women become depressed more frequently than men, a consistent pattern across cultures. Inflammation plays a key role in initiating depression among a subset of individuals, and depression also has inflammatory consequences. Notably, women experience higher levels of inflammation and greater autoimmune disease risk compared to men. In the current review, we explore the bidirectional relationship between inflammation and depression and describe how this link may be particularly relevant for women. Compared to men, women may be more vulnerable to inflammation-induced mood and behavior changes. For example, transient elevations in inflammation prompt greater feelings of loneliness and social disconnection for women than for men, which can contribute to the onset of depression. Women also appear to be disproportionately affected by several factors that elevate inflammation, including prior depression, somatic symptomatology, interpersonal stressors, childhood adversity, obesity, and physical inactivity. Relationship distress and obesity, both of which elevate depression risk, are also more strongly tied to inflammation for women than for men. Taken together, these findings suggest that women’s susceptibility to inflammation and its mood effects may contribute to sex differences in depression. Depression continues to be a leading cause of disability worldwide, with women experiencing greater risk than men. Due to the depression-inflammation connection, these patterns may promote additional health risks for women. Considering the impact of inflammation on women’s mental health may foster a better understanding of sex differences in depression, as well as the selection of effective depression treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Women experience higher rates of depression than men, a consistent pattern across cultures [1]. From puberty through their reproductive years, women have a roughly twofold higher risk for major depressive disorder (MDD) compared to men, with 21.3 % of women and 12.9 % of men experiencing major depressive episodes in their lifetimes [1, 2]. Multiple theories contribute to our understanding of this pattern, including those that highlight sex differences in biological vulnerability, need for affiliation, thought patterns, and emotion reactivity and regulation [3–5].

In addition, a thriving literature suggests that inflammation contributes to depression for some individuals via well-established mechanistic pathways [6, 7••]. Meta-analytic findings suggest that MDD patients have elevated inflammation levels compared to healthy controls, as measured by C-reactive protein (CRP; an inflammatory marker) and proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [8, 9]. Importantly, prospective studies indicate that elevated inflammation increases subsequent risk for depression [10]. Syndromal depression as well as subclinical depressive symptoms can promote exaggerated inflammatory responses to stressors [11•, 12], which can act to maintain depressive symptoms and elevate longer-term health risks.

Inflammation may be a key contributor to depression for women. Women have higher rates of autoimmune diseases compared to men, including a twofold to ninefold greater risk for lupus, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and rheumatoid arthritis [13]. Additionally, more women have clinically relevant elevations in CRP, an inflammatory marker indicating cardiovascular risk, compared to men [14]. Furthermore, multiple factors that elevate MDD risk can also promote inflammation, suggesting overlapping pathways. Several of these factors, including relationship distress, childhood adversity, and obesity, appear to affect women to a greater extent than men, which may help to explain sex differences in MDD risk.

In the current review, we explore how inflammation’s link to depression may be particularly relevant for women. First, we highlight evidence that inflammation contributes to depression. We then focus on the inflammatory consequences of depressive symptoms, relationship distress, childhood adversity, obesity, and physical inactivity, factors with particular relevance for women. Finally, we discuss these findings’ implications for women’s health and depression risk.

Inflammation: A Pathway to Depression

Proinflammatory cytokines can induce depressive symptoms by affecting neurotransmitter metabolism, impairing neuronal health, and altering brain activity in mood-relevant brain regions [6, 7]. Indeed, elevated inflammation plays an important role in the onset of depression for some individuals. For example, healthy women with higher CRP had more depressive symptoms over the subsequent 7-year follow-up period than those with lower initial CRP values [15]. Higher IL-6 in early life raises risk for MDD during young adulthood [16]. Similarly, a recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies showed that heightened CRP and IL-6 increase risk for depressive symptoms over time [10].

Laboratory studies have used vaccines, endotoxin, and cytokines to increase inflammation and study subsequent mood and behavior changes [7••, 17, 18]. Following immune challenges such as these, depression is more likely to develop among healthy adults with an MDD history, greater initial depressive symptoms, low social support, and susceptible genetic profiles than those without these risk factors [17, 19, 20]. Notably, women are more likely to have a depression history, which elevates risk for subsequent depression following inflammatory challenges.

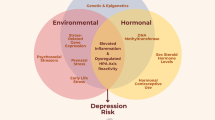

Women may also be more vulnerable to inflammation-induced mood and behavior changes compared to men. In a recent study, women and men had similar IL-6 and TNF-α responses following a low-dose endotoxin administration. However, women reported greater increases in depressed mood than men [21••]. Compared to men, women also reported feeling more lonely and disconnected from others in response to endotoxin administration. Furthermore, women who had larger IL-6 and TNF-α responses also reported feeling more lonely and socially disconnected than those with smaller cytokine responses; the magnitude of inflammatory responses was not related to social disconnection for men. Given that social disconnection plays a strong role in the onset of depression for women, sex differences in depression could be partially due to the greater impact of inflammation on social behavior for women. Accordingly, women may be more likely to develop mood symptoms in response to elevated inflammation. Next, we focus on biopsychosocial risk factors for increased inflammation (see Fig. 1).

Pathways from biopsychosocial risk factors to elevated inflammation and depressive symptoms, which fuel one another. These patterns may have particular relevance for women: a Women experience these risk factors for depression and inflammation at higher rates than men. b Initial evidence suggests that some of these factors (e.g., relationship distress and obesity) are more strongly tied to inflammation for women than for men. c Women have higher levels of inflammation and higher rates of autoimmune diseases compared to men. d Women become depressed more frequently than men. e Transient increases in inflammation affect women’s mood and social disconnection to a greater extent than their male counterparts

Biopsychosocial Risk Factors for Elevated Inflammation

Prior or Current Depressive Symptoms

Depression enhances inflammation, which may fuel further depressive symptoms over time [22••]. For example, those with more depressive symptoms had larger increases in CRP and IL-6 over several years compared to those with fewer depressive symptoms [15, 23]. Accordingly, depression and inflammation influence each other bidirectionally.

Depression also magnifies individuals’ inflammatory responses to stressors. People with MDD had larger IL-6 responses to a laboratory stressor than those without MDD [12]; subclinical depressive symptoms also enhanced stress-induced IL-6 [11•]. Additionally, childbirth evoked greater IL-6 increases in pregnant women with a prior history of depression compared to those without a history of depression [24]. Following influenza vaccination, pregnant women with more depressive symptoms had greater inflammatory responses than those with fewer depressive symptoms [25]. Furthermore, people with a depression history experience more frequent stressors and stronger emotional reactions to them than those without a depression history [26, 27]. Accordingly, people who were previously depressed may undergo stress responses more frequently than those who were not. In this way, women’s higher depression rates may have inflammatory consequences that promote further mood risk.

Somatic Symptomatology

Elevated inflammation can induce sickness behaviors such as fatigue, anhedonia, pain, and sleep changes [17, 28]. In laboratory models of elevated inflammation, these sickness behaviors often precede the onset of depressive symptoms and closely resemble the neurovegetative symptoms of major depression [28]. Although sickness behaviors can facilitate recovery from acute illness by conserving energy, they also enhance depressive symptoms and inflammation. Women’s depression appears to be more frequently characterized by these somatic symptoms than men’s depression [29]. In representative community samples, women were twice as likely as men to endorse somatic symptomatology, including sleep disturbance, fatigue, and appetite change [29].

Somatic symptoms can further fuel negative mood and inflammatory processes. For example, a brief, laboratory pain task elevated IL-6 [30], and reports of pain enhanced depression risk prospectively [31]. In a laboratory study, sleep loss led to increases in rheumatoid arthritis patients’ pain, depression, and fatigue [32]. People with sleep problems also had greater increases in CRP and IL-6 over time compared to their counterparts without sleep problems [33, 34•]. Furthermore, fatigued breast cancer survivors had larger IL-1β and IL-6 responses to a laboratory stressor compared to less fatigued survivors [35].

Women may be more vulnerable to the inflammatory effects of somatic symptoms. Following sleep deprivation, women experienced more persistent rises in IL-6 and TNF-α compared to men [36]. Furthermore, women reported more fatigue on average than men [37]. In addition, fatigue corresponded to higher CRP among women, but men’s fatigue was not associated with elevated inflammation [37]. Accordingly, women tend to experience somatic symptoms to a greater extent than men, which may have inflammatory consequences.

Relationship Distress

Relationship distress may impact women’s mood more than that of men [3]. For example, among opposite-sex twin pairs, interpersonal stressors such as low marital satisfaction and low social support predicted depression more strongly for women than for men [38]. Compared to men, women also reported feeling more responsible for others’ emotional needs and for maintaining relationships; these patterns contributed to depression-linked thinking styles such as rumination [5].

Marital Distress

Many adults’ closest relationship is with their spouse, and marital distress increases risk for medical problems including cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome [39, 40]. A stressful marriage promotes both depression and inflammation [41•, 42]. Importantly, the relationship between depression and marital distress is bidirectional; a depressed partner may present challenges that decrease marital quality over time [42]. Wives are typically affected by marital distress to a greater extent than their husbands [43]. For example, in response to marital conflict discussions, women exhibited more negative affect compared to men [44, 45].

Some evidence suggests that marital quality may be more closely related to inflammation among women than men. In the MIDUS study, women who reported lower spousal support had higher levels of IL-6 and CRP than those who reported higher support; the relationship between spousal support and inflammation was not significant for men [41•]. The presence of additional risk factors may amplify the effects of marital distress on inflammation. For example, abdominal fat releases proinflammatory cytokines, and IL-6 stimulates CRP production [46]. In a study of healthy married women, higher marital stress was associated with higher levels of CRP among women with larger waist circumferences [47]. For women with smaller waists, marital stress did not predict CRP levels. In this way, abdominal adiposity may contribute to the extent that marital distress alters inflammation for women.

Social Disconnection

Feeling socially disconnected in other relationships can also lead to depression. Indeed, lonelier adults were more likely to develop depressive symptoms over a 5-year follow-up period compared to those who were less lonely [48]. On the other hand, supportive relationships can protect against depression. For example, patients recovering from myocardial infarction who reported higher social support had fewer depressive symptoms 1 year later compared to their counterparts with lower social support, and this finding was stronger among women than men [49]. Further, depressed individuals with low social support were at greater risk for developing asthma compared to depressed people with high social support, suggesting that social support may buffer against some of the harmful health effects of depression [50].

Social disconnection also contributes to heightened inflammation. Healthy individuals who reported receiving less support from their friends, families, and spouses had higher levels of several inflammatory markers over the course of 5 years than those who reported more support [51]. In the MESA study, adults with lower social support had higher levels of CRP than those with higher social support [52]. Similarly, breast cancer patients who reported higher levels of social support before starting treatment had lower levels of inflammation 6 months after their treatment ended compared to those who reported lower social support [53]. A laboratory stressor provoked greater increases in IL-6, IL1-RA, and TNF-α among lonelier adults compared than those who were less lonely [54, 55]. Accordingly, feeling disconnected from others is a key risk factor for elevated inflammation.

Childhood Adversity

Adverse childhood events negatively impact inflammation and depression in adulthood. According to a worldwide study, approximately 39 % of adults experienced at least one form of childhood adversity in their lifetime, including interpersonal loss, parental maladjustment, maltreatment, illness, or economic adversity [56]. A history of adverse childhood events may be more common in women than men. In a large epidemiological study, women were approximately 1.5 times more likely to have experienced verbal abuse or severe physical abuse and 7.5 times more likely to experience inappropriate sexual contact as a child compared to their male counterparts [57]. Childhood maltreatment is a potent risk factor for depression. According to a recent meta-analysis, people who experienced childhood maltreatment have higher risk for recurrent and prolonged depressive episodes compared to those without maltreatment [58].

In addition to a heightened risk for depression, childhood adversity also has strong links to inflammation across the lifespan. In prospective studies, children who experienced adverse life events had elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP in later childhood and adolescence [59, 60]. The implications of childhood adversity persist into adulthood. People with a history of childhood adversity had elevated risk for heightened CRP and major depression at age 32 than those without a similar history [61]. Among older adults, people with a history of multiple adverse childhood events had higher levels of IL-6 than those without such a history, and childhood abuse was specifically related to higher levels of IL-6 and TNF-α [62]. A history of childhood adversity also boosts responsiveness to stressors. Individuals with a history of childhood abuse had heightened IL-6 responses to stressors in the laboratory as well as daily life compared to those with no history of childhood abuse [63, 64].

The link between adverse childhood experiences and adult inflammation may be partially explained by negative health patterns such as obesity. Childhood trauma is associated with higher BMI in adulthood, a key risk factor for heightened inflammation including CRP [65–67]. Indeed, obesity contributes to mood and inflammatory risks.

Obesity

Across the world, more women are obese than men, a characteristic that promotes both depression and inflammation [68]. Evidence suggests that health behaviors along with social and economic factors contribute to women’s elevated obesity risk. Women tend to be less physically active than men, and physical inactivity increases risk for obesity [69, 70]. Additionally, women in countries with higher economic inequality and gender inequality have particularly elevated rates of obesity, demonstrating an important link between socioeconomic status and women’s health [71].

Obesity and depression often co-occur, fueling one another [72]. For example, older adults with more depressive symptoms gained more abdominal fat over the course of 5 years compared to those with fewer depressive symptoms [73]. In a recent meta-analysis, Luppino and colleagues explored the bidirectional relationships between obesity and depression [74]. Obese individuals were 55 % more likely to become depressed than their lower BMI counterparts [74]. Similarly, depressed adults were 58 % more likely to become obese compared to people who were not depressed [74]. These results are particularly relevant for women, as they are vulnerable to both obesity and depression [75].

Inflammation plays a key role in linking obesity and depression. Adipose tissue releases proinflammatory cytokines and fosters chronic low-grade inflammation [46]. Indeed, obese people have higher concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, CRP, and TNF-α, compared to normal weight individuals [76, 77]. In addition, waist circumference and physical inactivity predict higher inflammation and increased risk for heart disease [78]. Just as obesity contributes to inflammation, elevated inflammation can promote obesity by stimulating the HPA axis and contributing to accumulation of fat tissue [46]. Importantly, the relationship between body fat and CRP is stronger for women (r = 0.54) than for men (r = 0.24), as demonstrated in a recent meta-analysis [79•].

Obesity also primes exaggerated inflammatory responses to stressors. For example, young women with greater abdominal obesity had larger stress-induced inflammatory responses compared to those with less abdominal obesity [80]. Furthermore, obesity’s impact on reactivity appears to persist for subsequent stressors. Following an initial stressor, overweight healthy adults had larger IL-6 responses to a second stressful task compared to normal weight individuals [81]. Accordingly, repeated stressors may persistently elevate inflammation for obese women, a pathway that could increase their depression and health risks over time. Other factors that promote obesity, including physical inactivity, may be particularly detrimental for women.

Physical Inactivity

A strong research base supports the mood benefits of exercise [82], and more active individuals also have lower levels of inflammation than those who are less active [83]. Individuals who reported at least 2.5 h of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week had lower levels of CRP and IL-6 at baseline and 10 years later compared to their less active counterparts [83]. Physical activity may limit obesity-related inflammation in some cases. For example, postmenopausal, overweight women with higher energy expenditure (i.e., kilocalories burned) throughout the day had lower levels of CRP than their more sedentary counterparts, even after adjusting for fat mass [84].

Even among those who exercise regularly, spending more time engaging in sedentary activities that involve sitting and little movement is detrimental. For example, more sedentary individuals had higher IL-6 than those who were less sedentary, and these differences remained after accounting for BMI and other daily physical activity [85•]. Indeed, a growing literature suggests that sedentary time may uniquely contribute to inflammation.

On average, women are less active than men, and thus, the ties between physical inactivity and inflammation may be particularly relevant. In the NHANES study, accelerometers were used to objectively measure activity levels [86, 87]. Throughout the life span, females consistently engaged in less physical activity than males, except during a brief period in older adulthood [86]. Younger women (under age 30) also had greater sedentary time compared to age-matched men [87]. These patterns are concerning, given that inactivity contributes to poor health and inflammation uniquely, as well as through other pathways, such as weight gain.

Conclusions

Inflammation may be a key pathway to consider in women’s depression for several reasons. Women have higher levels of inflammation and higher rates of autoimmune diseases compared to men [13, 14], both of which elevate subsequent depression risk [23, 88]. Transient increases in inflammation also affect women’s mood and social disconnection to a greater extent than their male counterparts [21••]. Relationship distress and obesity, both of which elevate depression risk, are more strongly tied to inflammation for women than for men [41•, 79]. Furthermore, women experience several risk factors for inflammation at higher rates than men, including obesity, physical inactivity, and childhood adversity [57, 68, 86]. Taken together, these findings suggest that women’s susceptibility to inflammation and its mood effects can contribute to sex differences in depression.

In effectively addressing women’s depression and inflammation, it may be helpful to consider the interplay of risk factors. For example, obese women report more fatigue than those who are not obese, and both of these factors increase inflammation [37]. When combined with a history of depression, marital distress has been linked to a slower metabolism, which could lead to weight gain and thus promote inflammation [89]. In addition, women are more likely to take on multiple social roles; as a result, they experience more frequent opportunities for stress compared to men [90]. These stressors may elevate inflammation, particularly among those with risk factors such as prior depression, obesity, and/or childhood adversity, which heighten inflammatory responses to stress.

Furthermore, women’s levels of reproductive hormones fluctuate throughout the life span, which has implications for inflammation. Estrogen levels increase during puberty, one factor that may contribute to increases in MDD among girls during adolescence [4, 91]. As reproductive hormones rise and fall during the menstrual cycle in premenopausal women, corresponding changes in CRP occur [92]. During menopausal transition (i.e., perimenopause), women experience more pronounced hormonal fluctuations, subsequently resulting in diminished estrogen levels following menopause [91, 93]. Due partially to low estrogen levels, postmenopausal women experience elevated inflammation, which may affect women’s health during aging [93–95]. Indeed, estrogen typically inhibits inflammation, and inflammatory processes play a role in atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and other age-related diseases later in life [94, 96, 97]. These complex relationships affect multiple other hormone mediators and neurotransmitters, providing promising targets for explaining sex differences in mood disorders [91].

On average, women live longer than men, and it is important to examine factors that alter women’s risk for health problems during aging [98]. Women have elevated rates of depression compared to men, and depression’s inflammatory consequences are linked to poor health. Heightened inflammation increases risk for age-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and metabolic syndrome [97]. For example, individuals with higher levels of CRP, IL-6, IL-18, and TNF-α are more likely to develop cardiovascular disease compared to those with lower inflammation [99]. Exaggerated inflammatory responses to immune challenges (e.g., stressors and pathogens) may also carry important health risks over time [22••]. However, laboratory endotoxin studies to date have focused primarily on male participants [18], and inclusion of more women represents an avenue for future research.

Depression continues to be a leading cause of disability worldwide, with women experiencing greater risk than men [100]. Due to the depression-inflammation connection, these patterns may promote additional health risks for women. Accordingly, successful prevention and treatment of women’s depression could have an immense public health impact. Given that women experience elevated inflammation compared to men [14], anti-inflammatory strategies may be particularly important in improving women’s health and mood. A variety of pharmacological treatments and lifestyle interventions can reduce inflammation and improve mood [6, 7••]. Considering the impact of inflammation on women’s mental health may foster a better understanding of sex differences in depression, as well as the selection of effective depression treatments.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Bromet E, Andrade LH, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Alonso J, de Girolamo G, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 2011;9(1):90.

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey I: lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Disord. 1993;29(2–3):85–96. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-G.

Cyranowski J, Frank E, Young E, Shear M. Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: a theoretical model. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):21–7. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21.

Hyde JS, Mezulis AH, Abramson LY. The ABCs of depression: integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychol Rev. 2008;115(2):291–313. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.291.

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Jackson B. Mediators of the gender difference in rumination. Psychol Women Q. 2001;25(1):37–47. doi:10.1111/1471-6402.00005.

Haroon E, Raison CL, Miller AH. Psychoneuroimmunology meets neuropsychopharmacology: translational implications of the impact of inflammation on behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):137–62. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.205.

Slavich GM, Irwin MR. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: A social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(3):774–815. This comprehensive review provides an in-depth, mechanistic discussion of how stress, depression, and inflammation impact one another, as well as how other key factors such as early life stress can play important roles in these processes.

Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(2):171–86. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b.

Liu Y, Ho RC-M, Mak A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. 2012;139(3):230–9. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.003.

Valkanova V, Ebmeier KP, Allan CL. CRP, IL-6 and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):736–44. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.004.

Fagundes CP, Glaser R, Hwang BS, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Depressive symptoms enhance stress-induced inflammatory responses. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;31:172–6. This study suggests that even lower levels of depressive symptoms can boost inflammatory responses under stress.

Pace T, Mletzko T, Alagbe O, Musselman D, Nemeroff C, Miller A, et al. Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. Am J Psychiatr. 2006;163(9):1630–3.

Quintero OL, Amador-Patarroyo MJ, Montoya-Ortiz G, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya J-M. Autoimmune disease and gender: plausible mechanisms for the female predominance of autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2012;38(2–3):J109–19. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2011.10.003.

Yang YC, Kozloski M. Sex differences in age trajectories of physiological dysregulation: inflammation, metabolic syndrome, and allostatic load. J Gerontol A: Biol Med Sci. 2011;66A(5):493–500. doi:10.1093/gerona/glr003.

Matthews KA, Schott LL, Bromberger JT, Cyranowski JM, Everson-Rose SA, Sowers M. Are there bi-directional associations between depressive symptoms and C-reactive protein in mid-life women? Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(1):96–101. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.08.005.

Khandaker G, Pearson R, Zammit S, Lewis G, Jones P. Association of serum interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein in childhood with depression and psychosis in young adult life: a population-based longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(10):1121–8. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1332.

Capuron L, Miller AH. Immune system to brain signaling: neuropsychopharmacological implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130(2):226–38. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.014.

Schedlowski M, Engler H, Grigoleit J-S. Endotoxin-induced experimental systemic inflammation in humans: a model to disentangle immune-to-brain communication. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;35:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2013.09.015.

Capuron L, Ravaud A, Miller AH, Dantzer R. Baseline mood and psychosocial characteristics of patients developing depressive symptoms during interleukin-2 and/or interferon-alpha cancer therapy. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18(3):205–13. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2003.11.004.

Udina M, Moreno-España J, Navinés R, Giménez D, Langohr K, Gratacòs M, et al. Serotonin and interleukin-6: the role of genetic polymorphisms in IFN-induced neuropsychiatric symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(9):1803–13. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.03.007.

Moieni M, Irwin MR, Jevtic I, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Eisenberger NI. Sex differences in depressive and socioemotional responses to an inflammatory challenge: Implications for sex differences in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015. doi:10.1038/npp.2015.17. In this key report of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, laboratory study of endotoxin responses, women appeared more vulnerable to the behavioral effects of inflammation compared to men. In response to endotoxin, women reported more depressive symptoms and social disconnection than men. Among women, those with greater inflammatory responses also had larger increases in social disconnection, one pathway that can help explain sex differences in depression.

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, & Fagundes CP (in press) Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. The American Journal of Psychiatry. This thoughtful review focuses on 'how' and 'for whom' depression and inflammation are linked, and discusses how this information may be used in clinical practice to enhance recovery and prevent recurrence.

Duivis HE, de Jonge P, Penninx BW, Na BY, Cohen BE, Whooley MA. Depressive symptoms, health behaviors, and subsequent inflammation in patients with coronary heart disease: prospective findings from the Heart and Soul study. Am J Psychiatr. 2011;168(9):913–20. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081163.

Maes M, Ombelet W, Jongh D, Kenis G, Bosmans E. The inflammatory response following delivery is amplified in women who previously suffered from major depression, suggesting that major depression is accompanied by a sensitization of the inflammatory response system. J Affect Disord. 2001;63(1–3):85–92. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00156-7.

Christian LM, Franco A, Iams JD, Sheridan J, Glaser R. Depressive symptoms predict exaggerated inflammatory responses to an in vivo immune challenge among pregnant women. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(1):49–53. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.05.055.

Husky MM, Mazure CM, Maciejewski PK, Swendsen JD. Past depression and gender interact to influence emotional reactivity to daily life stress. Cogn Ther Res. 2009;33(3):264–71.

Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(4):555.

Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46–56. doi:10.1038/nrn2297.

Silverstein B, Edwards T, Gamma A, Ajdacic-Gross V, Rossler W, Angst J. The role played by depression associated with somatic symptomatology in accounting for the gender difference in the prevalence of depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;48(2):257–63. doi:10.1007/s00127-012-0540-7.

Griffis CA, Breen EC, Compton P, Goldberg A, Witarama T, Kotlerman J, et al. Acute painful stress and inflammatory mediator production. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2013;20(3):127–33. doi:10.1159/000346199.

Hilderink PH, Burger H, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, Oude Voshaar RC. The temporal relation between pain and depression: results from the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(9):945–51. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182733fdd.

Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carrillo C, Sadeghi N, FitzGerald JD, Ranganath VK, et al. Sleep loss exacerbates fatigue, depression, and pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Sleep. 2012;35(4):537–43. doi:10.5665/sleep.1742.

Cho HJ, Seeman TE, Kiefe CI, Lauderdale DS, Irwin MR. Sleep disturbance and longitudinal risk of inflammation: moderating influences of social integration and social isolation in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;46:319–26. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2015.02.023.

Irwin MR. Why sleep is important for health: a psychoneuroimmunology perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66(1):143–72. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115205. This thorough paper reviews the current evidence linking sleep disturbances to inflammatory processes, and addresses the sex differences and health implications associated with these findings.

Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N, Olmstead R, Irwin MR, Cole SW. Inflammatory responses to psychological stress in fatigued breast cancer survivors: relationship to glucocorticoids. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(3):251–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2006.08.001.

Irwin MR, Carrillo C, Olmstead R. Sleep loss activates cellular markers of inflammation: sex differences. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(1):54–7. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.06.001.

Valentine RJ, McAuley E, Vieira VJ, Baynard T, Hu L, Evans EM, et al. Sex differences in the relationship between obesity, C-reactive protein, physical activity, depression, sleep quality and fatigue in older adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(5):643–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2008.12.003.

Kendler KS, Gardner CO. Sex differences in the pathways to major depression: a study of opposite-sex twin pairs. Am J Psychiatr. 2014;171(4):426–35. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13101375.

Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, McGinn MM. Marital quality and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(1):140–87. doi:10.1037/a0031859.

Whisman MA, Uebelacker LA. A longitudinal investigation of marital adjustment as a risk factor for metabolic syndrome. Health Psychol. 2012;31(1):80–6. doi:10.1037/a0025671.

Donoho CJ, Crimmins EM, Seeman TE. Marital quality, gender, and markers of inflammation in the MIDUS cohort. J Marriage Fam. 2013;75(1):127–41. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01023.x. This paper provides a well-written overview of the marital quality and inflammation literature, and explains how this link may differ for men and women. These MIDUS study results suggested spousal support was more strongly linked to inflammation for women than for men, even after accounting for other factors like health behaviors.

Whisman MA, Baucom DH. Intimate relationships and psychopathology. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;15(1):4–13. doi:10.1007/s10567-011-0107-2.

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(4):472–503. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472.

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Malarkey W, Chee M, Newton T, Cacioppo J, Mao H, et al. Negative behavior during marital conflict is associated with immunological down-regulation. Psychosom Med. 1993;55(5):395–409.

Mayne TJ, O’Leary A, McCrady B, Contrada R, Labouvie E. The differential effects of acute marital distress on emotional, physiological and immune functions in maritally distressed men and women. Psychol Health. 1997;12(2):277–88.

Kyrou I, Chrousos GP, Tsigos C. Stress, visceral obesity, and metabolic complications. In: Chrousos GP, Tsigos C, editors. Stress, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, vol. 1083. Oxford: Blackwell Science Publ; 2006. p. 77–110.

Shen B-J, Farrell KA, Penedo FJ, Schneiderman N, Orth-Gomer K. Waist circumference moderates the association between marital stress and c-reactive protein in middle-aged healthy women. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(3):258–64. doi:10.1007/s12160-010-9211-7.

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(2):453–63. doi:10.1037/a0017216.

Leifheit-Limson EC, Reid KJ, Kasl SV, Lin H, Jones PG, Buchanan DM, et al. The role of social support in health status and depressive symptoms after acute myocardial infarction: evidence for a stronger relationship among women. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(2):143–50. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.899815.

Loerbroks A, Apfelbacher CJ, Bosch JA, Stuermer T. Depressive symptoms, social support, and risk of adult asthma in a population-based cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(3):309–15. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d2f0f1.

Yang YC, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social support, social strain and inflammation: Evidence from a national longitudinal study of U.S. adults. Soc Sci Med. 2014;107:124–35. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.013.

Mezuk B, Diez Roux AV, Seeman T. Evaluating the buffering vs. direct effects hypotheses of emotional social support on inflammatory markers: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(8):1294–300. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2010.06.006.

Hughes S, Jaremka LM, Alfano CM, Glaser R, Povoski SP, Lipari AM, et al. Social support predicts inflammation, pain, and depressive symptoms: longitudinal relationships among breast cancer survivors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;42:38–44. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.12.016.

Hackett RA, Hamer M, Endrighi R, Brydon L, Steptoe A. Loneliness and stress-related inflammatory and neuroendocrine responses in older men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(11):1801–9. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.016.

Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Peng J, Bennett JM, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, et al. Loneliness promotes inflammation during acute stress. Psychol Sci. 2013;24(7):1089–97. doi:10.1177/0956797612464059.

Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):378–85. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499.

Keyes KM, Eaton NR, Krueger RF, McLaughlin KA, Wall MM, Grant BF, et al. Childhood maltreatment and the structure of common psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2012;200(2):107–15. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093062.

Nanni V, Uher R, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatr. 2012;169(2):141–51. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020335.

Miller GE, Cole SW. Clustering of depression and inflammation in adolescents previously exposed to childhood adversity. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(1):34–40. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.034.

Slopen N, Kubzansky LD, McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC. Childhood adversity and inflammatory processes in youth: a prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(2):188–200. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.05.013.

Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Pariante CM, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(12):1135–43.

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Gouin J-P, Weng N, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf DQ, Glaser R. Childhood adversity heightens the impact of later-life caregiving stress on telomere length and inflammation. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(1):16.

Carpenter LL, Gawuga CE, Tyrka AR, Lee JK, Anderson GM, Price LH. Association between plasma IL-6 response to acute stress and early-life adversity in healthy adults. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(13):2617–23. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.159.

Gouin J-P, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf D, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Childhood abuse and inflammatory responses to daily stressors. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44(2):287–92. doi:10.1007/s12160-012-9386-1.

Lacey RE, Kumari M, McMunn A. Parental separation in childhood and adult inflammation: the importance of material and psychosocial pathways. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(11):2476–84. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.05.007.

Raposa EB, Bower JE, Hammen CL, Najman JM, Brennan PA. A developmental pathway from early life stress to inflammation: the role of negative health behaviors. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(6):1268–74. doi:10.1177/0956797614530570.

Schrepf A, Markon K, Lutgendorf SK. From childhood trauma to elevated C-reactive protein in adulthood: the role of anxiety and emotional eating. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(5):327–36. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000072.

Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9 · 1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377(9765):557–67. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5.

Bauman A, Bull F, Chey T, Craig CL, Ainsworth BE, Sallis JF, et al. The International Prevalence Study on Physical Activity: results from 20 countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:21. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-6-21.

Guthold R, Ono T, Strong KL, Chatterji S, Morabia A. Worldwide variability in physical inactivity a 51-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):486–94. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.013.

Wells JCK, Marphatia AA, Cole TJ, McCoy D. Associations of economic and gender inequality with global obesity prevalence: understanding the female excess. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2012;75(3):482–90. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.029.

Zhao G, Ford ES, Li C, Tsai J, Dhingra S, Balluz LS. Waist circumference, abdominal obesity, and depression among overweight and obese U.S. adults: national health and nutrition examination survey 2005–2006. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:130. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-130.

Vogelzangs N, Kritchevsky SB, Beekman AT, Newman AB, Satterfield S, Simonsick EM, et al. Depressive symptoms and change in abdominal obesity among older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1386–93. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1386.

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BWJH, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):220–9. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2.

de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A, Penninx B, Zitman F, Cuijpers P. Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(2):230–5. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015.

Kim C-S, Park H-S, Kawada T, Kim J-H, Lim D, Hubbard NE, et al. Circulating levels of MCP-1 and IL-8 are elevated in human obese subjects and associated with obesity-related parameters. Int J Obes. 2006;30(9):1347–55. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803259.

Herder C, Peltonen M, Koenig W, Kraft I, Muller-Scholze S, Martin S, et al. Systemic immune mediators and lifestyle changes in the prevention of type 2 diabetes—results from the Finnish diabetes prevention study. Diabetes. 2006;55(8):2340–6. doi:10.2337/db05-1320.

Rana JS, Arsenault BJ, Despres J-P, Cote M, Talmud PJ, Ninio E, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers, physical activity, waist circumference, and risk of future coronary heart disease in healthy men and women. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(3):336–44. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp010.

Choi J, Joseph L, Pilote L. Obesity and C-reactive protein in various populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14(3):232–44. doi:10.1111/obr.12003. This meta-analysis provides an excellent test of the obesity-inflammation link across diverse samples. The results suggest that the relationship between obesity and CRP is larger among women than men.

Brydon L, Wright CE, O’Donnell K, Zachary I, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Stress-induced cytokine responses and central adiposity in young women. Int J Obes (2005). 2008;32(3):443–50. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803767.

McInnis CM, Thoma MV, Gianferante D, Hanlin L, Chen X, Breines JG, et al. Measures of adiposity predict interleukin-6 responses to repeated psychosocial stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;42:33–40. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.018.

Cooney G, Dwan K, Mead G. Exercise for depression. JAMA. 2014;311(23):2432–3.

Hamer M, Sabia S, Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Tabak AG, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Physical activity and inflammatory markers over 10 years follow-up in men and women from the Whitehall II Cohort Study. Circulation. 2012;126(8):928–33. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.103879.

Lavoie M-E, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Doucet E, Mignault D, Messier L, Bastard J-P, et al. Association between physical activity energy expenditure and inflammatory markers in sedentary overweight and obese women. Int J Obes. 2010;34(9):1387–95. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.55.

Henson J, Yates T, Edwardson CL, Khunti K, Talbot D, Gray LJ, et al. Sedentary time and markers of chronic low-grade inflammation in a high risk population. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e78350. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078350. This paper highlights the distinct role of sedentary behavior on inflammation. Adults with greater sedentary time, as measured by accelerometer, had higher IL-6 levels than those with less sedentary time, even after accounting for their BMI and levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity.

Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–8. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3.

Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, Buchowski MS, Beech BM, Pate RR, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(7):875–81. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm390.

Benros ME, Waltoft BL, Nordentoft M, Ostergaard SD, Eaton WW, Krogh J, et al. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for mood disorders: a nationwide study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(8):812–20. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1111.

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Jaremka L, Andridge R, Peng J, Habash D, Fagundes CP, et al. Marital discord, past depression, and metabolic responses to high-fat meals: interpersonal pathways to obesity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;52:239–50. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.11.018.

Terrill AL, Garofalo JP, Soliday E, Craft R. Multiple roles and stress burden in women: a conceptual model of heart disease risk. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2012;17(1):4–22. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9861.2011.00071.x.

Altemus M, Sarvaiya N, Neill Epperson C. Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35(3):320–30. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.05.004.

Gaskins AJ, Wilchesky M, Mumford SL, Whitcomb BW, Browne RW, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. Endogenous reproductive hormones and c-reactive protein across the menstrual cycle: the biocycle study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(5):423–31. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr343.

Figueroa-Vega N, Moreno-Frías C, Malacara JM. Alterations in adhesion molecules, pro-inflammatory cytokines and cell-derived microparticles contribute to intima-media thickness and symptoms in postmenopausal women. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0120990. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120990.

Kop WJ, & Mommersteeg PMC (2015) Psychoneuroimmunological pathways and sex differences in coronary artery disease: the role of inflammation and estrogen. In K. Orth-Gomér, N. Schneiderman, V. Vaccarino, & H.-C. Deter (Eds.), Psychosocial Stress and Cardiovascular Disease in Women (pp. 129–149). Springer International Publishing. Retrieved from http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-09241-6_9

Rubinow DR, Girdler SS. Hormones, heart disease, and health: individualized medicine versus throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(4):282–96. doi:10.1002/da.20810.

Moreau KL, Hildreth KL. Vascular aging across the menopause transition in healthy women. Adv Vasc Med. 2014;2014:e204390. doi:10.1155/2014/204390.

Michaud M, Balardy L, Moulis G, Gaudin C, Peyrot C, Vellas B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines, aging, and age-related diseases. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(12):877–82. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.009.

Xu J, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;168:1–8.

Kaptoge S, Seshasai SRK, Gao P, Freitag DF, Butterworth AS, Borglykke A, Danesh J (2013) Inflammatory cytokines and risk of coronary heart disease: new prospective study and updated meta-analysis. European Heart Journal, eht367. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht367

Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–223. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Heather M. Derry, Jennifer L. Kuo, and Spenser Hughes declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Avelina C. Padin has received a grant from the NIH.

Janice K. Kiecolt-Glaser has received grants from the NIH.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Sources of Funding

Work on this manuscript was supported in part by NIH grants CA172296, CA186251, and CA186720 and a Pelotonia Predoctoral Fellowship from the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Women’s Mental Health

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Derry, H.M., Padin, A.C., Kuo, J.L. et al. Sex Differences in Depression: Does Inflammation Play a Role?. Curr Psychiatry Rep 17, 78 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0618-5

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0618-5