Abstract

Purpose of Review

The purpose of this review is to synthesize the recently published scientific evidence on disparities in epidemiology and management of fragility hip fractures.

Recent Findings

There have been a number of investigations focusing on the presence of disparities in the epidemiology and management of fragility hip fractures. Race-, sex-, geographic-, socioeconomic-, and comorbidity-based disparities have been the primary focus of these investigations. Comparatively fewer studies have focused on why these disparities may exist and interventions to reduce disparities.

Summary

There are widespread and profound disparities in the epidemiology and management of fragility hip fractures. More studies are needed to understand why these disparities exist and how they can be addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is common in postmenopausal women as well as older adults in both sexes. Reduced bone mineral density seen in osteoporosis places patients at risk for fractures as a result of low-energy trauma [1]. These fragility fractures are common in the hip, spine, and wrist [2]. The most common mechanism of injury for fragility hip fractures is a fall [3]. There is an estimated 12.1% and 4.6% lifetime risk of fragility hip fracture for women and men, respectively [4]. It has been estimated that the worldwide annual incidence of hip fracture may increase from 1.6 million per year in 2000 to 4.5 million per year by 2050 due in part to the worldwide increases in life expectancy [5, 6]. Fragility hip fractures primarily consist of femoral neck fractures and intertrochanteric femur fractures, with femoral neck fractures accounting for approximately 58% [7]. The management of hip fractures is largely operative, consisting of hip arthroplasty or osteosynthesis for femoral neck fractures and osteosynthesis for intertrochanteric fractures due to the substantial morbidity and nonunion rates for conservative treatment [7, 8]. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend surgical treatment within 48 h of admission to reduce the risk for mortality and other complications [8, 9], although approximately 6.2% of patients may undergo nonsurgical treatment due to short life expectancy, poor pre-injury mobility, high risk for postoperative complications, or goals of care that are not consistent with surgery [10,11,12].

Racial and ethnic differences in health and healthcare outcomes have been identified in the epidemiology and management of a number of conditions after controlling for confounding factors [13, 14]. There have been overall improvements in key aspects of hip fracture care in recent years, with reductions rates of delayed surgery [15] and in mortality [16]. However, there remain disparities in key aspects of hip fracture care such as higher rates of hip fractures in neighborhoods with higher levels of socioeconomic deprivation [17,18,19,20] and increased delays in time to surgery for minority patients [21]. It is important to understand how health, the risk for hip fracture, and the care for these fractures may vary by the patient’s race and ethnicity, sex, and socioeconomic status. In this literature review, we review the existing evidence on disparities in the epidemiology and management of fragility hip fractures.

Disparities in Epidemiology

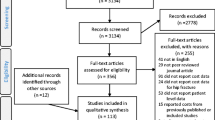

Studies evaluating disparities in the epidemiology of fragility hip fractures have primarily utilized large national administrative databases along with multivariable regression analysis to determine the association between a predictor such as patient race with the risk for fragility hip fracture after controlling for relevant confounders (Table 1). While these studies have generally reported differences in rates of fragility hip fractures across different patient groups, there are comparatively less studies evaluating the mechanisms for these differences.

Race

White patients have been shown to have increased rates of hip fracture compared to non-White patients. A retrospective analysis of the National Hospital Discharge Survey demonstrated that White women have a relative risk of hip fracture from 1.5 to 4.0 compared to non-White women for all ages after 40 [22]. A study evaluating hip fractures in CA reported that the odds of hip fracture were 41–74% lower for non-White women compared to White women and 51–75% lower for non-White men compared to White men [23]. Native Americans have also been shown to be at increased risk of hip fracture compared to White patients [24]. The association of race with the risk of fragility hip fracture is likely to be partially mediated by bone mineral density, as White patients are likely to have lower bone mineral density compared to Black patients [25], although this is not true with all groups as Asian patients have been shown to have lower bone mineral density and also lower risk for osteoporotic fracture [26]. Interestingly, rates of vitamin D deficiency do not seem to influence racial differences in rates of fragility hip fracture, as vitamin D deficiency has been reported to be higher in Black compared to White patients (91% vs. 61%) [27].

Sex

Female patients are at an increased risk for hip fracture compared to male patients [22]. Males are generally younger than female patients by 3–6 years at the time of hip fracture [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Males with hip fractures also generally have more medical comorbidities, with higher rates of alcohol use [28, 34], smoking [35], hypertension [34], renal disease [28, 29], renal stones [28], malignancy [29], congestive heart failure [29], COPD [29, 34, 36], diabetes [29], peripheral vascular disease [29, 34], myocardial infarction [29, 34], stroke [34], connective tissue disease [29], Parkinson disease [34], liver disease [29], as well as higher number of total comorbidities [37] and American Society of Anesthesiologists score [35] than females with hip fractures. Sex differences in rates of hip fracture may be due in large part to hormone changes in menopause and associated changes in bone mineral density [38], as well as differences in bone strength and geometry between the sexes [39,40,41].

Geographic Factors

There are considerable global geographic differences in hip fracture incidence. The incidence of hip fracture is highest in Europe and North America and lowest in Latin America and Africa for both men and women [6]. The age-adjusted rates of hip fractures in women are highest in Norway (532 per 100,000) and lowest in Nigeria (2 per 100,000). Similarly, the age-adjusted rate of hip fractures in men is also highest in Norway (281 per 100,000) and lowest in Nigeria (2 per 100,000) [6]. These differences may be attributed to differences in rates of osteoporosis distribution across countries which may be due to differences in environmental or societal factors such as sun exposure, physical activity, and diet.

Socioeconomic Deprivation

Socioeconomic status has also been shown to be a risk factor for fragility hip fracture. Adults age 50 or older residing in areas with higher levels of socioeconomic deprivation in Northern England have a higher incidence of hip fractures compared to those residing in other regions of England (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 2.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.00–2.12 for men; IRR 1.62, 95% CI 1.60–1.65 for women) [17]. A similar trend was also shown in Israel, with more socioeconomically deprived areas being associated with a higher incidence of hip fracture in the National Trauma Registry [18]. Patients with higher income in the Danish health registry were less likely to sustain hip fracture (odds ratio [OR] 0.78, 95% CI 0.72–0.85 for highest quintile of income compared to third quintile) [19]. Hip fractures were shown to be associated with higher levels of deprivation in the French national hospital discharge database as well (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.05 for the fourth quartile of socioeconomic deprivation compared to the first quartile) [20]. The mechanism for the effect of socioeconomic status on risk for fragility hip fracture is unclear but may be due to differences in nutritional status or ability to take time off work to attend preventative healthcare appointments. Future work may seek to further elucidate the mechanisms for disparities in hip fracture incidence across groups with differing levels of socioeconomic deprivation and whether these vary across geographic areas. This knowledge would be particularly helpful in designing interventions.

Medical Comorbidities

Differences in the incidence of fragility hip fractures have also been associated with certain medical comorbidities such as neurological disorders and chronic disease that affect bone mineralization such as chronic renal disease. A meta-analysis demonstrated that patients with Parkinson disease have been shown to have an increased risk of hip fracture compared to patients without Parkinson disease (hazard ratio 3.13, 95% CI 2.53–3.87) [42].

Additionally, patients with vision loss had a 154% increased odds of hip fracture compared to patients without vision loss in a study of Medicare claims data from 2014 [43]. Patients with chronic kidney disease [44], dementia [45], and those chronically using corticosteroids [46] have also been shown to be at risk for hip fractures. Interventions to reduce fall risk may represent an important area of future work to reduce the incidence of hip fractures in certain populations such as individuals with dementia or Parkinson disease.

Disparities in Management

In addition to the known differences in rates of hip fractures, disparities in the management of patients with hip fractures and those at risk for hip fractures are also well established. Prior work in this area has investigated disparities in primary prevention, surgical timing, choice of treatment, type of anesthesia used in surgery, and secondary prevention (Table 2). Similar to the work focusing on disparities in epidemiology, considerably less work has focused on why these disparities in management may exist.

Primary Prevention

The US Preventative Services Task Force (USPTF) and the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommend osteoporosis screening for all women age 65 or older as well as younger women with risk factors for osteoporosis, while the American Association of Endocrinology recommends osteoporosis screening for all postmenopausal women age 50 or older [47]. A nationwide study demonstrated that Black women were less likely to be screened for osteoporosis across all age groups (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.87–0.97 for age 80 or older) [48]. A multi-state study showed that Black women were less likely than White women to undergo screening for osteoporosis (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.43–0.62) [49]. Similarly, Black women were less likely to undergo screening in a study of two outpatient internal medicine clinics (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.22–0.68) [50]. Clinicians have been shown to mention osteoporosis less commonly in the medical record for Black women compared to White women (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.11–0.37), suggesting that lower rates of clinician recommendations for screening may contribute to these differences [50]. A number of other reasons for racial disparities in screening have been proposed, including clinicians inappropriately deeming Black patients at low risk for osteoporosis, incorrect clinician assumptions about differences in bone biology, and higher rates of comorbidities in Black patients which may take more clinic time to address [50].

Surgical Timing

The AAOS recommends surgical treatment of fragility hip fractures within 48 h of admission in order to optimize outcomes [8]. A number of prior studies have demonstrated evidence of racial and ethnic differences in surgical timing. A retrospective study including five hospitals in a single health system showed that Black patients waited 7 h longer for surgery than White patients (41 vs. 34 h, P = 0.01). This was largely driven by a difference in the community hospitals but not in the tertiary hospitals [51]. A study using an all-payer database from NY state showed that Black patients were more likely to undergo surgery after more than 2 days of initial presentation (OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.42–1.57) compared to White patients, and both Black and Asian patients were more likely to undergo delayed surgery for all levels of social deprivation when stratified by degree of social deprivation [21]. Similar findings were also reported in a study by Amen et al. using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, where it was shown that Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients had a greater odds of surgery being delayed by 2 days or more compared to White patients after controlling for patient factors including medical comorbidities, hospital characteristics, insurance, and socioeconomic status [15]. An analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank showed that Black patients were more likely to experience delay of 48 h or greater to surgery when compared to White patients on unadjusted analysis [52]. Another study using the same data source showed that patients with Black, Hispanic, and other race and ethnicity had a 20–97% increase in odds of delay of more than 48 h to surgical treatment of hip fracture after controlling for confounder variables [53]. An analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database showed that Black patients were less likely to undergo surgical treatment of hip fracture within 48 h when compared to White patients on multivariable analysis (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.29–1.58) [54]. In contrast, a retrospective study evaluating patients in an integrated managed care system with standardized protocols for management showed no difference in odds of delay of 48 h or more in surgical timing [55]. Racial differences in timing of surgery may be at least partially due to differences in timing of diagnosis and initial workup. A retrospective study including five hospitals in a single health system showed that Black patients had a 3-h longer wait time for radiographic evaluation than White patients [51]. Other potential reasons may be related to access to appropriate care as a study from an integrated managed care system showed no difference in odds of surgical treatment performed greater than 2 days after presentation for Black patients [55]; another study evaluating outcomes after twelve different surgical procedures found no differences in outcomes by race for patients included in universally insured population compared to those without universal insurance [56].

There is also evidence of other demographic differences in surgical timing. Lower educational level, older age, and male sex were associated with delay of greater than 2 days on multivariable analysis in a study evaluating all hospital discharges in the Piedmont region of Northwest Italy [57]. Insurance has not been a focus in many studies evaluating surgical timing but was not associated with delay greater than 48 h to surgery in a study using the National Trauma Data Bank [53]. A study evaluating older residents of Ontario, Canada, demonstrated no difference in time to surgery for female versus male patients with hip fractures [58].

Choice of Treatment

The primary treatments for displaced femoral neck fractures among older adults are total hip arthroplasty or hemiarthroplasty. Total hip arthroplasty may result in superior function and lower risk of reoperation compared to hemiarthroplasty, but total hip arthroplasty may not be the best option in low demand patients, patients without pre-existing hip degenerative disease, or patients with more comorbidities due to increased risk of dislocation, increased blood loss, and longer operative time compared to hemiarthroplasty [59, 60].

Multiple studies have evaluated the association between race and treatment choice for patients with femoral neck fractures and did not find a significant association. In an analysis of national Medicare claims data, White patients had no difference in rates of hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.84–1.02) [61]. Similarly, no difference in rates of total hip arthroplasty rather than hemiarthroplasty were seen for minorities compared to White patients (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.32–1.61 for Black vs. White) [62].

An analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) demonstrated that Asian or Pacific Islander patients had a 49% lower odds of receiving total hip arthroplasty rather than hemiarthroplasty (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.33–0.78, P = 0.002) after controlling for patient and facility factors. Notably, other racial and ethnic differences in treatment between White patients and Hispanic, Native American, or other race/ethnicity patients were not observed [63].

An analysis of the NIS demonstrated that patients with Medicaid insurance had a 29% lower odds of undergoing total hip arthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fracture than patients with Medicare insurance (OR 1.45, 95% CI 0.55–0.92) after controlling for patient and facility factors [63]. An analysis of the UK National Hip Fracture Database showed that increasing levels of socioeconomic deprivation were associated with lower likelihood of undergoing total hip arthroplasty for hip fracture (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.66–0.88 for most deprived compared to least deprived quintile) among patients meeting eligibility criteria for possible total hip arthroplasty [64].

It is important to note that some of the factors that may lead surgeons to choose total hip arthroplasty rather than hemiarthroplasty such as baseline activity level and pre-existing hip pain or degenerative disease [59] are likely to be poorly captured in large databases and may bias the inferences from these studies. One potential barrier to undergoing total hip arthroplasty for hip fracture may be the availability of surgeons comfortable with this procedure. It has been shown that patients undergoing elective total hip arthroplasty with low volume surgeons have higher risk for complications, revision surgery, and death [65, 66]. Centralization of care to centers with surgeons comfortable with performing total hip arthroplasty surgery may be one possible solution [64].

Type of Anesthesia

A study evaluating older residents of Ontario, Canada, revealed that women were less likely to receive perioperative geriatric care (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.72–0.88) as well as anesthesia consultation (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.80–0.98); there was no difference in rates of neuraxial or regional analgesia by sex. The authors did not evaluate the association between race and ethnicity and treatment [58]. Schaar et al. [67] reported that Black patients were less likely than White patients to receive neuraxial anesthesia as a primary anesthetic, but Black patients were more likely to receive a regional block.

Outpatient Management of Osteoporosis Following Hip Fracture

Females were more likely than males to be treated for osteoporosis following hip fracture (OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.47–4.31) in a study evaluating patients at three hospitals in Hawaii on multivariable analysis. This same study did not identify differences by race and ethnicity in osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture [68]. A study of men age 50 or older with hip fractures in the US Department of Veterans Affairs system showed no racial or ethnic differences in any osteoporosis care, medication for osteoporosis, or dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan on multivariable analysis [69].

Interventions to Reduce Disparities

Geriatric Fracture Programs

There has been considerably less work aimed at addressing disparities in the epidemiology and management of fragility hip fractures. One potential intervention that may be beneficial in reducing disparities in management of fragility hip fractures is the development and implementation of geriatric fracture programs. These programs aim to minimize time to surgery, avoid iatrogenic illness through collaboration between orthopedic surgeons and geriatric medicine physicians, reduce variation in care through standardized protocols, and facilitate efficient discharge planning through early engagement with social workers and other care navigators [70,71,72]. These programs have also been shown to result in financial benefits to hospitals [73, 74]. The impact of geriatric fracture programs in disparities in the management of geriatric hip fractures is less well understood. Parola et al. demonstrated that there was no difference in delay to surgery by gender or race and ethnicity in a single institution study evaluating outcomes after instituting a geriatric fracture program at a single center [75]. The effect of geriatric fracture program implementation at other centers on disparities in management of fragility hip fractures is largely unknown, but the promising results of the study by Parola et al. suggest that development and implementation of standardized and protocol-driven care pathways may result in reductions in disparities.

Healthcare Policy

There has also been some work aimed at understanding the impact of federal reimbursement policies on the care of patients with fragility hip fractures. Bundled payment programs for primary total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty include both elective surgeries as well as surgeries for fracture. Programs such as the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) [76], the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative (BPCI) [77], and BPCI Advanced [78] include a single risk-adjusted payment to hospitals for care delivered during the encounter and the 90-day postoperative period [79]. Through these programs, hospitals that keep their spending below a quality-adjusted target price keep the difference (“reward”), while those that exceed the target price require to repay the difference to Medicare (“penalty”), thereby incentivizing hospitals to achieve high-quality outcomes with measured spending. Notably, the CJR sets separate and higher target prices for episodes where patients undergo total hip replacements for hip fractures (compared to total hip replacement for degenerative disease) to recognize the higher spending that is needed for hip fracture patients. These programs have resulted in savings to both Medicare and hospitals [80] but have also been shown to be associated with worsening disparities in rates of elective total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty [81, 82]. Recent adjustments to these models for primary total hip and knee replacements have aimed to address disparities in care by introducing risk adjustment for clinical (adjustment forage and hierarchical condition category score [a comorbidity index]) and social risk (adjustment for dual-eligibility for both Medicare and Medicaid, a marker for socioeconomic risk) [83]. The impact of these policies on disparities in management remains to be seen; however, the majority of patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty are undergoing elective surgery for degenerative disease, and there are concerns about differences in outcomes and inadequate cost adjustment in these programs when applied to patients undergoing primary arthroplasty for fracture [84,85,86,87]. Desires to optimize treatment of all fragility hip fractures including those not treated with arthroplasty led some to suggest implementation of bundled payment programs for the treatment of hip fractures [88, 89]. The effects of the recent implementation of a bundled payment program for operative treatment hip and femur fractures without arthroplasty, BPCI Advanced [90], on these disparities are unknown. Future work may aim to better understand the effects of these policies on disparities in management.

Conclusions

A number of disparities are present in the epidemiology and management of geriatric hip fractures despite controlling for potential confounding factors. The majority of work in this area has been focused on understanding which disparities exist, but comparatively fewer studies have focused on why these differences may exist or how they could be addressed. It is important that clinicians, policymakers, and researchers are aware of how these factors may influence health and patient care. Future work should focus on determining the extent to which these differences may be due to differences in clinical appropriateness and patient preferences versus bias on the part of clinicians or the healthcare system, the effects of disparities on patient health outcomes, understand why these disparities may exist, evaluate the effect of programs and policies on disparities, and also seek to develop and implement interventions to reduce these disparities. Future work may also seek to better understand the association of socioeconomic deprivation on the epidemiology, management, and outcomes of fragility hip fractures and how this may vary across geographic areas. Reduction in disparities in the epidemiology and management of fragility hip fractures will help improve equity in orthopedic care.

References

Riggs BL, Melton LJ III. The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: insights afforded by epidemiology. Bone. 1995;17:505S-511S.

Dennison E, Cooper C. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Horm Res. 2000;54:58–63.

Moreland BL, Legha JK, Thomas KE, Burns ER. Hip fracture-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations and deaths by mechanism of injury among adults Aged 65 and Older, United States 2019. J Aging Health. 2022;0:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/08982643221132450

Hopkins RB, Pullenayegum E, Goeree R, Adachi JD, Papaioannou A, Leslie WD, et al. Estimation of the lifetime risk of hip fracture for women and men in Canada. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:921–7.

Cooper C, Cole Z, Holroyd C, Earl S, Harvey N, Dennison E, et al. Secular trends in the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures and the IOF CSA Working Group on Fracture Epidemiology Europe PMC Funders Group. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1277–88. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3546313/pdf/ukmss-36681.pdf.

Cauley JA, Chalhoub D, Kassem AM, Fuleihan GEH. Geographic and ethnic disparities in osteoporotic fractures. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:338–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2014.51. (Nature Publishing Group).

Tsuda Y, Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, Ogawa S, Kawano H, Tanaka S. Association between dementia and postoperative complications after hip fracture surgery in the elderly: analysis of 87,654 patients using a national administrative database. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135:1511–7 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg).

Roberts KC, Brox WT, Jevsevar DS, Sevarino K. Management of hip fractures in the elderly. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:131–7.

Ryan DJ, Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D, Egol KA, Zuckerman JD. Delay in hip fracture surgery: An analysis of patient-specific and hospital-specific risk factors. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:343–8.

Loggers SAI, Van Lieshout EMM, Joosse P, Verhofstad MHJ, Willems HC. Prognosis of nonoperative treatment in elderly patients with a hip fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2020;51:2407–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2020.08.027. (Elsevier Ltd).

Neuman MD, Fleisher LA, Even-Shoshan O, Mi L, Silber JH. Nonoperative care for hip fracture in the elderly: the influence of race, income, and comorbidities. Med Care. 2010;48:314–20.

Khan AZ, Rames RD, Miller AN. Clinical management of osteoporotic fractures. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018;16:299–311.

Weinstein JN, Geller A, Negussie Y, Baciu A. Communities in action: pathways to health equity. National Academies Press. 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425848/. Accessed 21 Sept 2022.

Penner LA, Hagiwara N, Eggly S, Gaertner SL, Albrecht TL, Dovidio JF. Racial healthcare disparities: a social psychological analysis. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2013;24:70–122.

Amen TB, Varady NH, Shannon EM, Chopra A, Rajaee S, Chen AF. Racial and ethnic disparities in hip fracture surgery care in the United States from 2006 to 2015: a nationwide trends study. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30:E182–90.

Downey C, Kelly M, Quinlan JF. Changing trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture - a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2019;10:166–75.

Bhimjiyani A, Neuburger J, Jones T, Ben-Shlomo Y, Gregson CL. Inequalities in hip fracture incidence are greatest in the North of England: regional analysis of the effects of social deprivation on hip fracture incidence across England. Public Health. 2018;162:25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.05.002. (Elsevier Ltd).

Goldman S, Radomislensky I, Ziv A, Abbod N, Bahouth H, Bala M, et al. The impact of neighborhood socioeconomic disparities on injury. Int J Public Health. 2018;63:855–63.

Hansen L, Judge A, Javaid MK, Cooper C. Social inequality and fractures- secular trends in the Danish population : a case-control study. Osteoporos Int. 2019;29:2243–50.

Héquette-Ruz R, Beuscart JB, Ficheur G, Chazard E, Guillaume E, Paccou J, et al. Hip fractures and characteristics of living area: a fine-scale spatial analysis in France. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31:1353–60.

Dy CJ, Lane JM, Pan TJ, Parks ML, Lyman S. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in hip fracture care. J Bone Jt Surg - Am. 2016;98:858–65.

Farmer ME, White LR, Brody JA, Bailey KR. Race and sex differences in hip fracture incidence. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:1374–80.

Sullivan KJ, Husak LE, Altebarmakian M, Brox WT. Demographic factors in hip fracture incidence and mortality rates in California, 2000–2011. J Orthop Surg Res. 2016;11:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-015-0332-3.

Salamon E, Leslie WD, Metge CJ, Dale J, Yuen CK. Increased incidence of hip fractures in American Indians residing in Northern latitudes. J BONE Miner Res. BLACKWELL SCIENCE INC 350 MAIN ST, MALDEN, MA 02148; 1997. p. 148.

Raffat SK, Shaikh AB, Sarim M, Syed AR. Bone mineral density comparison of total body, lumbar and thoracic: an exploratory study. J Pak Med Assoc Pakistan. 2015;65:388–91.

Khandewal S, Chandra M, Lo JC. Clinical characteristics, bone mineral density and non-vertebral osteoporotic fracture outcomes among post-menopausal U.S. South Asian Women. Bone. 2012;51:1025–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2012.08.118. (Elsevier Inc.).

Khazai N, Judd SE, Tangpricha V. Calcium and vitamin D: Skeletal and extraskeletal health. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:110–7.

Becker C, Crow S, Toman J, Lipton C, McMahon DJ, Macaulay W, et al. Characteristics of elderly patients admitted to an urban tertiary care hospital with osteoporotic fractures: correlations with risk factors, fracture type, gender and ethnicity. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:410–6.

Kannegaard PN, van der Mark S, Eiken P, Abrahamsen B. Excess mortality in men compared with women following a hip fracture. National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival. Age Ageing. 2010;39:203–9.

Löfman O, Berglund K, Larsson L, Toss G. Changes in hip fracture epidemiology: redistribution between ages, genders and fracture types. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:18–25.

Samuelsson B, Hedström MI, Ponzer S, Söderqvist A, Samnegård E, Thorngren KG, et al. Gender differences and cognitive aspects on functional outcome after hip fracture - a 2 years’ follow-up of 2,134 patients. Age Ageing. 2009;38:686–92.

Wehren LE, Hawkes WG, Orwig DL, Hebel JR, Zimmerman SI, Magaziner J. Gender differences in mortality after hip fracture: the role of infection. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:2231–7.

Holt G, Smith R, Duncan K, Hutchison JD, Gregori A. Gender differences in epidemiology and outcome after hip fracture: evidence from the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser B. 2008;90:480–3.

Hawkes WG, Wehren L, Orwig D, Hebel JR, Magaziner J. Gender differences in functioning after hip fracture. J Gerontol - Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:495–9.

Endo Y, Aharonoff GB, Zuckerman JD, Egol KA, Koval KJ. Gender differences in patients with hip fracture: a greater risk of morbidity and mortality in men. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:29–35.

Arinzon Z, Shabat S, Peisakh A, Gepstein R, Berner YN. Gender differences influence the outcome of geriatric rehabilitation following hip fracture. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50:86–91.

Pande I, Scott DL, O’Neill TW, Pritchard C, Woolf AD, Davis MJ. Quality of life, morbidity, and mortality after low trauma hip fracture in men. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:87–92.

Lane JM, Russell L, Khan SN. Osteoporosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;372:139–50.

Sigurdsson G, Aspelund T, Chang M, Jonsdottir B, Sigurdsson S, Eiriksdottir G, et al. Increasing sex difference in bone strength in old age: the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik study (AGES-REYKJAVIK). Bone. 2006;39:644–51.

Riggs BL, Melton LJ, Robb RA, Camp JJ, Atkinson EJ, Peterson JM, et al. Population-based study of age and sex differences in bone volumetric density, size, geometry, and structure at different skeletal sites. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1945–54.

Cawthon PM. Gender differences in osteoporosis and fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1900–5.

Hosseinzadeh A, Khalili M, Sedighi B, Iranpour S, Haghdoost AA. Parkinson’s disease and risk of hip fracture: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Belg Italy. 2018;118:201–10.

Hamedani AG, Vanderbeek BL, Willis AW. Blindness and visual impairment in the Medicare population: disparities and association with hip fracture and neuropsychiatric outcomes. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2019;26:279–85.

Robertson L, Black C, Fluck N, Gordon S, Hollick R, Nguyen H, et al. Hip fracture incidence and mortality in chronic kidney disease: the GLOMMS-II record linkage cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:1–10.

Wang HK, Hung CM, Lin SH, Tai YC, Lu K, Liliang PC, et al. Increased risk of hip fractures in patients with dementia: a nationwide population-based study. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:1–8.

Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Joseph Melton L, et al. A meta-analysis of prior corticosteroid use and fracture risk. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:893–9.

Ruiz-Esteves KN, Teysir J, Schatoff D, Yu EW, Burnett-Bowie SAM. Disparities in osteoporosis care among postmenopausal women in the United States. Maturitas. 2022;156:25–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.10.010. (Elsevier B.V.).

Gillespie CW, Morin PE. Trends and disparities in osteoporosis screening among women in the United States, 2008–2014. Am J Med. 2017;130:306–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.10.018.

Neuner JM, Zhang X, Sparapani R, Laud PW, Nattinger AB. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in bone density testing before and after hip fracture. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1239–45.

Miller RG, Ashar BH, Cohen J, Camp M, Coombs C, Johnson E, et al. Disparities in osteoporosis screening between at-risk African-American and White women. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:847–51.

Ali I, Vattigunta S, Jang JM, Hannan CV, Ahmed MS, Linton B, et al. Racial disparities are present in the timing of radiographic assessment and surgical treatment of hip fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:455–61.

Jarman MP, Sokas C, Dalton MK, Castillo-Angeles M, Uribe-Leitz T, Heng M, et al. The impact of delayed management of fall-related hip fracture management on health outcomes for African American older adults. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;90:942–50.

Bhatti UF, Shah AA, Williams AM, Biesterveld BE, Okafor C, Ilahi ON, et al. Delay in hip fracture repair in the elderly: a missed opportunity towards achieving better outcomes. J Surg Res. 2021;266:142–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2021.03.027. (Elsevier Inc.).

Nayar SK, Marrache M, Ali I, Bressner J, Raad M, Shafiq B, et al. Racial disparity in time to surgery and complications for hip fracture patients. CiOS Clin Orthop Surg. 2020;12:430–4.

Okike K, Chan PH, Prentice HA, Paxton EW, Navarro RA. Association between race and ethnicity and hip fracture outcomes in a universally insured population. J Bone Jt Surg - Am. 2018;100:1126–31.

Schoenfeld AJ, Jiang W, Harris MB, Cooper Z, Koehlmoos T, Learn PA, et al. Association between race and postoperative outcomes in a universally insured population versus patients in the state of California. Ann Surg. 2017;266:267–73.

Petrelli A, De Luca G, Landriscina T, Costa G, Gnavi R. Effect of socioeconomic status on surgery waiting times and mortality after hip fractures in Italy. J Healthc Qual. 2017;40:209–16.

Cho N, Boland L, McIsaac DI. The association of female sex with application of evidence-based practice recommendations for perioperative care in hip fracture surgery. CMAJ. 2019;191:E151–8.

Florschutz AV, Langford JR, Haidukewych GJ, Koval KJ. Femoral neck fractures: current Management. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:121–9.

Li X, Luo J. Hemiarthroplasty compared to total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of femoral neck fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16:1–9.

Fanuele JC, Lurie JD, Zhou W, Koval KJ, Weinstein JN. Variation in hip fracture treatment: are black and white patients treated equally? Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2009;38:13–7.

Rudasill SE, Dattilo JR, Liu J, Kamath AF. Hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty: is there a racial bias in treatment selection for femoral neck fractures? Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2019;10:215145931984174.

Dangelmajer S, Yang A, Githens M, Harris AHS, Bishop JA. Disparities in total hip arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty in the management of geriatric femoral neck fractures. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2017;8:155–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/2151458517720991.

Perry DC, Metcalfe D, Griffin XL, Costa ML. Inequalities in use of total hip arthroplasty for hip fracture: population based study. BMJ. 2016;353.

Katz JN, Phillips CB, Baron JA, Fossel AH, Mahomed NN, Barrett J, et al. Association of hospital and surgeon volume of total hip replacement with functional status and satisfaction three years following surgery. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:560–8.

Losina E, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Katz JN. Early failures of total hip replacement: effect of surgeon volume. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1338–43.

Schaar AN, Finneran JJ, Gabriel RA. Association of race and receipt of regional anesthesia for hip fracture surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2023;0:1–7.

Nguyen ET, Posas-Mendoza T, Siu AM, Ahn HJ, Choi SY, Lim SY. Low rates of osteoporosis treatment after hospitalization for hip fracture in Hawaii. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29:1827–32.

Solimeo SL, McCoy K, Reisinger HS, Adler RA, Vaughan SM. Factors associated with osteoporosis care of men hospitalized for hip fracture: a retrospective cohort study. JBMR Plus. 2019;3:1–8.

Sinvani L, Goldin M, Roofeh R, Idriss N, Goldman A, Klein Z, et al. Implementation of hip fracture co-management program (AGS CoCare: Ortho®) in a large health system. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1706–13.

Kelly M, Kates SL. Geriatric fracture centers—improved patient care and economic benefits: English Version. Unfallchirurg. 2017;120:1–4.

O’Mara-Gardner K, Redfern RE, Bair JM. Establishing a geriatric hip fracture program at a level 1 community trauma center. Orthop Nurs. 2020;39:171–9.

Rocca GJD, Moylan KC, Crist BD, Volgas DA, Stannard JP, Mehr DR. Comanagement of geriatric patients with hip fractures: a retrospective, controlled, cohort study. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2013;4:10–5.

Kates SL, Mendelson DA, Friedman SM. The value of an organized fracture program for the elderly: Early results. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25:233–7.

Parola R, Neal WH, Konda SR, Ganta A, Egol KA. No differences between white and non-white patients in terms of care quality metrics, complications, and death after hip fracture surgery when standardized care pathways are used. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2022;481:324–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000002142.

US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Comprehensive care for joint replacement model [Internet].CMS.gov. 2023. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/cjr. Accessed 28 Feb 2023.

US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Bundled payments for care improvement (BPCI) initiative: general information [Internet]. CMS.gov. 2022. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/bundled-payments.

US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). BPCI advanced [Internet]. CMS.gov. 2023. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/bpci-advanced.

Ellimoottil C, Ryan AM, Hou H, Dupree J, Hallstrom B, Miller DC. Implications of the definition of an episode of care used in the comprehensive care for joint replacement model. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:49–54.

Navathe AS, Troxel AB, Liao JM, Nan N, Zhu J, Zhong W, et al. Cost of joint replacement using bundled payment models. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:214–22.

Kim H, Meath THA, Quiñones AR, McConnell KJ, Ibrahim SA. Association of Medicare mandatory bundled payment program with the receipt of elective hip and knee replacement in White, Black, and Hispanic beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e211772. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1772.

Thirukumaran CP, Kim Y, Cai X, Ricciardi BF, Li Y, Fiscella KA, et al. Association of the comprehensive care for joint replacement model with disparities in the use of total hip and total knee replacement. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:1–15.

Three-year RM. Medicare program: comprehensive care for joint replacement model three-year extension and changes to episode definition and pricing; Medicare and Medicaid programs; policies and regulatory revisions in response to the COVID-19 public health emergency [Internet]. 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-05-03/pdf/2021-09097.pdf. Accessed 11 May 2022.

Skibicki H, Yayac M, Krueger CA, Courtney PM. Target price adjustment for hip fractures is not sufficient in the bundled payments for care improvement initiative. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36:47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.07.069. (Elsevier).

Yoon RS, Mahure SA, Hutzler LH, Iorio R, Bosco JA. Hip arthroplasty for fracture vs elective care: one bundle does not fit all. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:2353–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.061.

Cairns MA, Ostrum RE, Clement RC. Refining risk adjustment for the proposed CMS surgical hip and femur fracture treatment bundled payment program. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100-A:269–77. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.17.00327.

Schroer WC, Diesfeld PJ, LeMarr AR, Morton DJ, Reedy ME. Hip fracture does not belong in the elective arthroplasty bundle: presentation, outcomes, and service utilization differ in fracture arthroplasty care. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:S56-60 (United States).

Malik AT, Khan SN, Ly TV, Phieffer L, Quatman CE. The “hip fracture” bundle—experiences, challenges, and opportunities. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2020;11:1–7.

Antonova E, Boye ME, Sen N, O’Sullivan AK, Burge R. Can bundled payment improve quality and efficiency of care for patients with hip fractures? J Aging Soc Policy. 2015;27:1–20.

Cooper KB, Mears SC, Siegel ER, Stambough JB, Bumpass DB, Cherney SM. The hip and femur fracture bundle: preliminary findings from a tertiary hospital. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S761-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2022.03.059. (Elsevier Inc.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Caroline P. Thirukumaran, MBBS, MHA, PhD, had the idea for the article. Derek T. Schloemann, MD, MPHS, performed the literature search and drafted the work. Caroline P. Thirukumaran, MBBS, MHA, PhD, Derek. T. Schloemann, MD, MPHS, and Benjamin F. Ricciardi, MD critically revised the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Schloemann reports grants from the University of Rochester and the American Foundation for Surgery of the Hand, outside the submitted work. Dr. Ricciardi reports grants from National Institutes of Health and Johnson and Johnson, outside the submitted work. Dr. Thirukumaran reports grants from National Institutes of Health, outside the submitted work. Dr. Thirukumaran reports honoraria from Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health, Brown University, outside the submitted work. Dr. Thirukumaran reports serving as the section editor of the disparities section of Current Osteoporosis Reports and as assistant editor for the disparities section of Anesthesia and Analgesia.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Schloemann, D.T., Ricciardi, B.F. & Thirukumaran, C.P. Disparities in the Epidemiology and Management of Fragility Hip Fractures. Curr Osteoporos Rep 21, 567–577 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-023-00806-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-023-00806-6