Abstract

We examined whether eyewitness confidence, familiarity with the defendant (defined as number of prior exposures), and eyewitness age (Study 1 only) influenced mock jurors in a murder trial. Participants read a criminal mock trial transcript where the eyewitness reported seeing the defendant once or many times (vs. none) and answered questions relating to the defendant’s guilt, culpability, and the accuracy of the eyewitness’ identification. In Studies 1 and 2 (N = 542 and N = 169, respectively) only confidence influenced jurors’ judgments with more guilt judgments and higher likelihood of identification accuracy when the witness espoused high (vs. low) confidence. Study 3 (N = 179) utilized a stronger operationalization of familiarity by explicitly stating the number of times the eyewitness had seen the defendant prior to the crime (e.g., 0, 10, or 20 times). Mock jurors were more likely to believe that the defendant was guilty when the eyewitness had seen him 10 times prior to the crime compared to zero times. Additionally, there was a trend for more favorable perceptions of the eyewitness as familiarity with the defendant increased. These results suggest that in some cases, familiarity between an eyewitness and defendant can impact mock juror decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Influence of Familiar and Confident Eyewitnesses on Mock Jurors’ Judgments

Research examining the influence of eyewitness identification on jurors’ decision-making has found that it is highly influential (Devenport et al. 1997; Wells and Olson 2003). However, the majority of the research examining the influence of eyewitness identification focuses on stranger identifications, that is, an identification of a person not known to the eyewitness. Given that researchers have estimated that almost half of identifications in the real world involve someone familiar to the eyewitness (e.g., Flowe et al. 2011), it also is important to examine how jurors perceive familiar identifications, that is, an identification of a person that is known to the eyewitness.

One variable that may interact with this shared familiarity is eyewitness age. The research examining the influence of eyewitness age on jurors’ decision has yielded mixed results, especially when case type is varied (i.e., sexual abuse versus non-sexual abuse; Pozzulo et al. 2006); moreover, these results are framed in light of stranger identifications. Child eyewitnesses are typically viewed more negatively than older eyewitnesses in non-sexual abuse, stranger, cases (e.g., Bruer and Pozzulo 2014; Goodman et al. 1987; Pozzulo et al. 2014); therefore, it can be speculated that mock jurors may perceive a familiar identification made by a child eyewitness more favorably compared to a stranger identification as the child reports knowing the defendant in some capacity. Little is known regarding how eyewitness age may influence jurors’ perceptions of an identification made of a familiar person which is troublesome given that a child victim is typically familiar with suspects in maltreatment cases (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2015). Similarly, confidence may also play more of a role in jurors’ judgments when the eyewitness is rating his or her confidence in the identification of a familiar, as opposed to unfamiliar, person. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to examine whether an eyewitness’ age, confidence in identification decision, and familiarity with the defendant influenced mock jurors’ judgments.

Given that stranger eyewitness identifications are highly influential in jurors’ judgments, familiar identifications may be perceived as even more indicative of a defendant’s guilt, as mock jurors may assume that familiarity would increase accuracy. When an eyewitness identifies a stranger, and this information is presented in court, jurors often have difficulty distinguishing between accurate and inaccurate eyewitnesses (Wells and Olson 2003). There is also evidence of similar difficulties in familiar identification cases. Joseph Abbitt is one such case where he was charged and convicted of assault based, in part, on the basis of two eyewitness’ testimony who stated that their attacker looked like a man who had previously lived in the area and had been to their home before, Joseph Abbitt (The National Registry of Exonerations 2018). After 14 years, DNA was tested from the rape kits and Abbitt was ruled out as a suspect. Because of the real-world occurrence of familiar identifications, it is important to understand how it influences jurors’ judgments so that we can better distinguish between guilty and innocent suspects.

Familiar Identifications

Given the relatively new direction of examining eyewitness-defendant familiarity, there is not yet one concrete definition of familiarity in a forensic context. As a result, it is possible to examine the definition of familiarity in other areas of research. Social psychologists have studied how familiarity occurs and provides a basis for understanding and defining the concept of familiarity. One such theory posited by social psychologists is the mere exposure effect (Zajonc 1968). The mere exposure effect suggests that the more we are exposed to a stimulus, the more familiar we become with that stimulus. In the realm of juror decision-making, as the number of exposures between the eyewitness and defendant increase, so should the perceived familiarity between them (e.g., Moreland and Beach 1992; Moreland and Zajonc 1982). Mandler (2008) also suggests that exposure duration, that is, how long we are exposed to a stimulus, influences familiarity such that increased exposure results in increased familiarity. Research examining the impact of exposure on eyewitness memory has found that increased exposure to a perpetrator increases an eyewitness’ accuracy when they are asked to make an identification from a lineup (Bornstein et al. 2012; Leippe et al. 1991; Memon et al. 2003). Increased exposure duration has also been found to increase the accuracy of child eyewitnesses (Cain et al. 2005); however, this finding is not always consistent (e.g., Gross and Hayne 1996). Given the little research that has examined familiarity in a legal context, not much is known at this time how familiarity may influence eyewitness identification in different scenarios (e.g., stressful situations).

The mere exposure effect and exposure duration are, perhaps, the most common ways in which familiarity has been defined when examining the influence of familiarity on mock jurors’ decisions. For example, Lindsay et al. (1986) examined the influence of exposure duration on mock jurors’ judgments. The eyewitness was described as either seeing the defendant for 5 s, 30 min, or an additional 30 min with interaction. No impact of exposure duration was found; however, when the eyewitness was exposed to the criminal for only 5 s, mock jurors indicated that the eyewitness had significantly less time to view the perpetrator compared to the other two conditions. To take this one step further, Pozzulo et al. (2014) examined the number of exposures between eyewitness and defendant. Specifically, the eyewitness was described as seeing the defendant zero, three, or six times prior to the crime. No influence of the number of exposures was found, thus suggesting that mock jurors may not perceive seeing someone six times as indicative enough of familiarity to influence their verdict or their perceptions of the witness.

To further test this, Sheahan et al. (2018) increased the number of exposures and examined whether seeing the defendant eight times prior to the crime (in comparison to zero) would be influential. The eyewitness was described as having seen the defendant eight times in a convenience store. Sheahan et al. found that compared to never having seen the defendant before, seeing him eight times prior to the crime was influential such that mock jurors were more likely to determine that the defendant was guilty when the eyewitness was familiar with the defendant compared to when there was no shared familiarity. While there was this influence on verdict decisions, there was no influence of familiarity on mock jurors’ perceptions of the eyewitness, similar to Pozzulo et al. (2014).

Vallano et al. (2018) examined the number of exposures and its influence on mock jurors’ judgments; however, no specific number of exposures was given, familiarity was described as having never seen the defendant prior to the crime, seeing him once, or seeing him many times; familiarity was not influential in jurors’ judgments. A second study was conducted utilizing a stronger conceptualization of familiarity, in which contextual details surrounding the prior exposure the witness had to the defendant was provided (i.e., how long before the crime the prior exposure occurred). Vallano et al. found that when the eyewitness was described as being familiar with the defendant, mock jurors were more likely to believe the defendant was guilty and that the identification of the defendant was accurate on both dichotomous and continuous measures; however, the effect was curvilinear. When the eyewitness had minimal exposure to the defendant, there was an increase in perceived guilt and identification accuracy compared to both the stranger and extensive exposure.

Other researchers have taken a different approach to familiarity through defining it as type of relationship shared (e.g., Pica et al. 2017). Pica et al. conceptualized familiarity as stranger, acquaintance (i.e., lunch monitor), or a familiar person (i.e., former teacher). Pica et al. (2017) found that mock jurors were more likely to assign higher guilt ratings to the defendant when he shared a familiar relationship with the eyewitness. In a follow-up study, the authors found that mock jurors were still more likely to assign higher guilt ratings when the witness was described as being a familiar person to the witness (i.e., their uncle). Given that there is no clear-cut definition of familiarity, and the mixed findings examining the influence of familiarity, the current studies sought to examine how many exposures are needed to establish that perception of familiarity. Given that only one study has found an influence with eight exposures (Sheahan et al. 2018), the current studies examined whether a specific number of reported exposures was needed for jurors to believe that the eyewitness and defendant shared a level of familiarity and whether it would influence their judgments.

Eyewitness Age and Familiarity

Eyewitnesses of all ages can be called to testify in court. The age of the eyewitness has been extensively studied; however, the results have been inconsistent with some research finding older eyewitnesses are perceived more favorably than younger eyewitnesses (e.g., Bruer and Pozzulo 2014; Goodman et al. 1987; Pozzulo et al. 2014) while other research has found the opposite (e.g., Ross et al. 1990). Past research examining the combined influence of age and familiarity has generally found that it does not sway mock jurors’ verdict decisions or perceptions (e.g., Pozzulo et al. 2014; Sheahan et al. 2018). Sheahan et al. suggest that the fact the eyewitness and defendant shared a familiar relationship was strong enough to where eyewitness age became an irrelevant factor for mock jurors to consider. Despite past research suggesting age and familiarity do not impact mock juror decisions, it is possible that the mock jurors did not perceive the familiarity to be enough to improve children’s accuracy. Given that children are often perceived as poorer eyewitnesses compared to older eyewitnesses in non-sexual abuse cases, it may be possible that a shared familiarity with the defendant would increase mock jurors’ perceptions of child eyewitnesses for these types of non-sexual crimes, depending on how familiarity is operationalized. Past research has found that increased familiarity, in terms of exposure, may increase child eyewitness accuracy (Cain et al. 2005) and does increase adolescent (e.g., Sheahan and Pozzulo under review) and adult accuracy (e.g., Bornstein et al. 2012); as such, this is an important interaction to consider. Therefore, the current study aimed to examine the role of age in combination with a stronger manipulation of familiarity.

Eyewitness Confidence and Familiarity

One of the most well-researched indicators of eyewitness identification accuracy is confidence (Sauer and Brewer 2015; Sporer et al. 1995). Generally speaking, high (vs. low) confidence identifications occurring under “pristine” conditions (e.g., good lighting, close proximity to the perpetrator) are more indicative of defendant guilt (Wixted and Wells 2017). Research additionally finds that jurors are accordingly persuaded by these high confidence identifications, as they are more likely to judge the defendant as guilty and the identification as accurate (Brewer and Burke 2002; Cutler et al. 1988). However, the majority of this research has focused primarily on stranger identifications. Given that there are general assumptions of how memory works (i.e., it is easier to remember someone we have seen before versus someone we have never seen), it can be speculated that jurors may perceive a high confidence identification of a familiar person even more influential.

To date, we know of only one study that has systematically examined the influence of confidence and familiar identifications on mock jurors’ decisions. Specifically, Vallano et al. (2018) examined whether an eyewitness who had seen the defendant many times, once, or never prior to the crime and was either highly confident or not confident in the identification decision, impacted juror’ judgments. Results supported previous research that has examined confidence and stranger identifications. Specifically, they found that when the eyewitness made an identification with high confidence, mock jurors were more likely to believe the identification was accurate and the defendant was guilty.

Study 1

The purpose of Study 1 was to examine whether eyewitness age, familiarity, and eyewitness confidence influenced mock jurors’ judgments. Study 1 was identical to that of Vallano et al. (2018) with the exception of it being a Canadian sample. We predicted that when the eyewitness reported seeing the defendant many times prior to the commission of the crime, there would be more guilty verdicts for the defendant. Additionally, when the eyewitness reported being highly confident in her identification decision, we predicted there would be more guilty verdicts for the defendant. Lastly, we predicted that confidence would play more of a role in jurors’ judgments when the eyewitness and defendants were strangers. Specifically, that when the eyewitness identified a stranger with high confidence, it would be more influential compared to when a stranger identification was made with low confidence.

Method

Participants

Undergraduate students (N = 542; 71.2% female) were recruited from a psychology participant pool at a university in Eastern Ontario, Canada. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 70 years old (M = 20.48, SD = 5.62). The majority of participants were identified as White/Caucasian (69.7%), with a considerable amount identifying as Asian (12.8%), and smaller amounts identifying as Black/African Canadian (8.5%), Latin American (1.1%), Aboriginal-Canadian (1.5%), and mixed or other (6.3%). Participants received course credit for their participation.

Design

The present study utilized a 3 (eyewitness age = 15 vs. 45 vs. 75 years) × 2 (confidence = sure vs. unsure) × 3 (familiarity with the defendant: seen many times before vs. seen once before vs. never seen before) between-subjects factorial design resulting in 18 conditions.

Materials and Procedure

Data were collected through the online survey tool Qualtrics. Participants were provided with the link to the study materials (see below) upon signing up for the study.

Trial Transcript

Eighteen versions of a seven-page criminal trial transcript were created that were identical except in regard to eyewitness age, confidence, and familiarity with the defendant. Each transcript began with instructions from the judge, followed by excerpts from the trial which involved a murder at a bus stop including testimony from four witnesses (i.e., a police officer, the eyewitness, defendant’s girlfriend, and defendant). The transcript concluded with closing statements from the lawyers and legal guidelines and instructions to the jury members.

Juror Questionnaire

Participants then rendered judgments concerning the dependent variables: the accuracy of the eyewitness’ identification, whether the defendant was the shooter, and defendant guilt. Next, participants rated several aspects of the eyewitness’s witnessing experience: view, attention, length of exposure to the perpetrator, and the amount of distance between the eyewitness and perpetrator (e.g., 1 = poor view, 7 = good view). Participants also rated the certainty, credibility, and honesty of the eyewitness’s identification (e.g., 1 = not credible, 7 = very credible). Finally, participants completed several questions regarding the general effects of certain estimator variables on eyewitness identification accuracy (e.g., the presence of a weapon). Embedded within these questions were items that specifically assessed participants’ beliefs about the accuracy of familiar compared to stranger identifications.

Upon completion, participants were debriefed and thanked for their participation.

Results and Discussion

Dichotomous Responses

There were two primary questions of interest: (1) do you think that the defendant is guilty of the murder (yes/no) and (2) do you believe that the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant is accurate (yes/no). Two separate sequential logistic regressions were conducted with eyewitness age, eyewitness confidence, and familiarity in the model to assess independent and combined effects on mock jurors’ dichotomous decisions.

Model 1 included only the main effects, Model 2 included the main effects and two-way interaction, and Model 3 included the main effects, two-way interactions, and three-way interaction. When examining whether mock jurors believed the defendant was guilty of the murder, Model 1 was significant (χ2(5) = 29.49, p < 0.001). Additionally, Models 2 and 3 were significant (χ2(13) = 32.62, p = 0.002 and χ2(17) = 34.65, p = 0.007, respectively). There were no significant effects in Model 3, and as such, Model 2 was retained. Only a significant effect of eyewitness confidence emerged (B = 0.78, SE = 0.40, p = 0.05). Mock jurors were more likely to believe the defendant was guilty when the eyewitness was confident (vs. not confident) in her identification. The remaining effects were not significant.

When examining whether mock jurors believed the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant was accurate, Model 1 was significant (χ2(5) = 41.43, p < 0.001). Additionally, Models 2 and 3 were significant (χ2(13) = 44.18, p < 0.001 and χ2(17) = 44.68, p < 0.002, respectively). There were no significant effects in Model 3, and as such, Model 2 was retained. Only a significant effect of eyewitness confidence emerged (B = 0.79, SE = 0.40, p = 0.05). Mock jurors were more likely to believe the defendant was guilty when the eyewitness was confident in her identification. The remaining effects were not significant.

Continuous Responses

There were four primary questions of interest: (1) how likely is it that the defendant is guilty of the murder, (2) do you believe that the defendant is the shooter, (3) how likely is it that the defendant is the shooter, and (4) how likely is it that the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant was accurate. Given that all four dependent variables were significantly correlated (p < 0.001), a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to determine whether eyewitness age, eyewitness confidence, and eyewitness familiarity with the defendant influenced mock jurors’ perceptions. Using Wilk’s λ, there was a significant multivariate effect of eyewitness confidence (F(4, 495) = 6.50, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.05). Univariate effects indicated significance for all dependent variables [the likelihood of guilt, F(1, 498) = 19.13, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.04, the belief that the defendant was the shooter, F(1, 498) = 17.94, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.05 = .04, the likelihood the defendant was the shooter, F(1, 498) = 16.60, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.03, and the likelihood of the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant being accurate, F(1, 498) = 24.89, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.05 (see Table 1 for descriptives). Increased eyewitness confidence influenced jurors to believe that the defendant was guilty, the defendant was the shooter, and an increased likelihood that the defendant was the shooter and the eyewitness’ identification was accurate. Using Wilk’s λ, there also was a significant multivariate three-way interaction between eyewitness age, eyewitness confidence, and eyewitness familiarity with the defendant (F(16, 1512.88) = 1.76, p = 0.03, partial η2 = 0.01). However, none the univariate effects were significant.

Perceptions of the Eyewitness

A series of questions were asked regarding the certainty, credibility, reliability, and honesty of the eyewitness’ identification on 1 (not at all) to 7 (very) Likert-type scales. As all four questions were significantly correlated (p < 0.001), a composite scale was created (α = 0.82). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine whether eyewitness age, confidence, and familiarity influenced mock jurors’ perceptions of the eyewitness’ identification. Only a significant effect of confidence emerged (F(1, 499) = 298.81, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.38). When the eyewitness was confident in her identification decision, she was perceived more favorably (M = 5.07, SD = 1.04) compared to when she was not confident (M = 3.43, SD = 1.11). The remaining effects were not significant.

Perceptions of Familiarity

Similar to Vallano et al. (2018), the current study examined whether mock jurors believed that prior exposure corresponded with familiarity. Mock jurors responded to two post-manipulation questions: (1) do witnesses who have seen a person before make more accurate identifications than those who have not seen a person before and (2) do witnesses who have seen a person many times before make more accurate identifications than those who have seen a person once before? Given that mock jurors answered this question on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), we classified responses from 1 to 3 as in disagreement with the proposition, responses from 5 to 7 as in agreement with the proposition, and a response of 4 as equivocal (the midpoint of the scale).

Overall, 54.2% of participants agreed that witnesses who have seen a person before make more accurate identifications than those who have not seen the person before (M = 4.61, SD = 1.46). A bivariate linear regression was then conducted to determine whether mock jurors’ familiarity perceptions were associated with mock jurors’ judgments on all four continuous variables. An increase in mock jurors’ beliefs regarding the accuracy of familiar identifications corresponded with an increase in the likelihood of defendant guilt (B = 0.35, SE = 0.05, t = 7.68, p < 0.001), belief that the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.45, SE = 0.05, t = 8.78, p < 0.001), the likelihood the defendant was the shooter (B = .36, SE = 0.05, t = 7.56, p < 0.001), and the likelihood the eyewitness’ identification was accurate (B = 0.35, SE = 0.05, t = 7.58, p < 0.001).

Overall, 68.6% of mock jurors agreed that witnesses who have seen a person many times before make more accurate identifications than those who saw the person only once before (M = 5.14, SD = 1.46). An increase in mock jurors’ beliefs regarding the accuracy of familiar identifications corresponded with an increase in the likelihood of defendant guilt (B = 0.23, SE = 0.05, t = 4.95, p < 0.001), belief that the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.31, SE = 0.05, t = 5.89, p < 0.001), the likelihood the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.25, SE = 0.05, t = 5.03, p < 0.001), and the likelihood the eyewitness’ identification was accurate (B = 0.24, SE = 0.05, t = 5.07, p < 0.001).

The results of Study 1 are in correspondence with previous research that has found increased confidence in more persuasive to jurors (e.g., Brewer and Burke 2002; Cutler et al. 1988; Sporer et al. 1995) in addition to previous research that has not found familiarity, defined as increasing exposures, to be influential (e.g., Pozzulo et al. 2014). Given that the current study stated that the witness had only seen the defendant before, the lack of interaction may be one factor jurors took into account.

Study 2

Similar to previous research (e.g., Pozzulo et al. 2014; Vallano et al. 2018), the number of exposures of familiarity did not influence mock jurors’ judgments. Bruce et al. (2001) examined participants’ ability to identify familiar and unfamiliar faces from CCTV clips and suggest that an additional component in addition to exposure must be present (i.e., interaction) in order for familiarity to be established. Given that Sheahan et al. (2018) found that when the eyewitness saw the defendant eight times in a convenience store and found an effect of familiarity, Study 2 added a prior interaction between eyewitness and perpetrator to determine whether this created an enhanced perception of familiarity. Previous research has found that adding more contextual information to the basis of familiarity can enhance that sense of familiarity and be influential (e.g., Vallano et al. 2018). Additionally, eyewitness age was dropped for Study 2 as no effects were found in Study 1. Given the findings of Study 1, we again predicted that confident eyewitnesses would be more influential than low confident witnesses. We also predicted that eyewitnesses who reported seeing the defendant many times (and thus interacting with the defendant many times) would produce more guilty verdicts than when the eyewitness and defendant were strangers. Lastly, we predicted there to be an interaction between confidence and familiarity such that there would be more guilty verdicts for the defendant when the eyewitness reported being more familiar with a confident identification of the defendant compared to when the eyewitness reported the defendant was a stranger and an identification made with no confidence.

Method

Participants

Undergraduate students (N = 169; 66.9% female) were recruited from a psychology participant pool from a university in Eastern Ontario, Canada. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 51 years old (M = 19.91, SD = 4.02). The majority of participants identified as White/Caucasian (69.8%), with a considerable amount identifying as Asian (14.2%) and smaller amounts identifying as Black/African American (6.5%), Latin American (0.6%), Aboriginal-Canadian (3.0%), and those that identified themselves as mixed or other (5.9%). Participants received course credit for their participation.

Design

The present study utilized a 2 (confidence: sure vs. unsure) × 3 (familiarity with the defendant: seen many times before with interaction vs. seen once before with interaction vs. never seen before) between-subjects factorial design.

Materials and Procedure

The materials and procedure were identical to that of Study 1 with the exception of the removal of eyewitness age in the trial transcript and the addition of the prior interaction between eyewitness and alleged perpetrator and how many times the eyewitness saw the defendant prior to the crime.

Results and Discussion

Dichotomous Responses

There were two primary questions of interest: (1) do you think that the defendant is guilty of the murder (yes/no) and (2) do you believe that the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant is accurate (yes/no). Two separate sequential logistic regressions were conducted to determine whether eyewitness confidence and familiarity influenced mock jurors’ dichotomous decisions. When examining whether mock jurors believed the defendant was guilty of the murder, Model 1 was not significant (χ2(3) = 5.14, p = 0.16), as such Models 2 and 3 were not examined given their inability to add to the overall model. When examining whether mock jurors believed that the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant was accurate, Models 1 and 2 were significant (χ2(3) = 11.78, p = 0.008 and χ2(5) = 12.44, p = 0.03), respectively. However, no significant effects were obtained in Model 2 thus suggesting the included variables did not account for a significant amount of the variance in defendant guilt. As such, Model 1 was retained. Similar to Study 1, only a significant effect of confidence emerged (B = 0.86, SE = 0.33, p = 0.008). Mock jurors were more likely to believe the eyewitness’ identification was accurate when she exhibited high (vs. low) confidence. The remaining effects were not significant.

Continuous Responses

There were four primary questions of interest: (1) how likely is it that the defendant is guilty of the murder, (2) do you believe that the defendant is the shooter, (3) how likely is it that the defendant is the shooter, and (4) how likely is it that the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant was accurate. Given that all four dependent variables were significantly correlated (p < 0.001), a MANOVA was conducted to determine whether eyewitness confidence and familiarity influenced mock jurors’ perceptions. Only a significant multivariate effect of confidence emerged using Wilk’s λ (F(4, 145) = 4.08, p = 0.004, partial η2 = 10). All univariate effects were significant: the likelihood of guilt (F(1, 148) = 8.91, p = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.06), the belief that the defendant was the shooter (F(1, 148) = 4.44, p = 0.04, partial η2 = 0.03), the likelihood the defendant was the shooter (F(1, 148) = 4.63, p = 0.03, partial η2 = 0.03), and the likelihood of the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant being accurate (F(1, 148) = 11.97, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.08) (see Table 2). Mock jurors were more apt to believe that the defendant was guilty and the shooter when the eyewitness’ confidence was high (vs. low); moreover, the likelihood that the defendant was the shooter and the eyewitness’ identification was accurate when her confidence was high (vs. low).

Perceptions of the Eyewitness

A series of questions were asked that pertained to the certainty, credibility, reliability, and honesty of the eyewitness’ identification on 1 (not at all) to 7 (very) Likert-type scales. All four questions were significantly correlated (p < 0.001), and as such, a composite scale was created (α = 0.76). A two-way ANOVA was conducted to determine whether eyewitness confidence and familiarity influenced mock jurors’ perceptions of the eyewitness’ identification. Similar to Study 1, only a significant effect of confidence emerged (F(1, 144) = 78.15, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.35). Mock jurors were more likely to hold positive perceptions of the eyewitness’ identification when she was confident (M = 4.81, SD = 1.10) compared to not confident (M = 3.33, SD = 0.90).

Perceptions of Familiarity

When examining mock jurors’ responses to familiarity in general, 55.6% agreed that witnesses who have seen a person before are more accurate than those who have not seen the person before (M = 4.64, SD = 1.57). A bivariate linear regression was then conducted to determine whether mock jurors’ familiarity perceptions influenced mock jurors’ judgments on all four continuous variables. An increase in mock jurors’ beliefs regarding the accuracy of familiar identifications corresponded with an increase in the likelihood of defendant guilt (B = 0.24, SE = 0.08, t = 2.97, p = 0.003), belief that the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.26, SE = 0.09, t = 2.93, p = 0.004), the likelihood the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.27, SE = 0.08, t = 3.36, p = 0.001), and the likelihood the eyewitness’ identification was accurate (B = 0.22, SE = 0.08, t = 2.90, p = 0.004). We then examined their perceptions of seeing a person many times and 72.2% of mock jurors agreed that witnesses who have seen a person many times are more accurate than those who saw the person only once (M = 5.37, SD = 1.38). An increase in mock jurors’ beliefs regarding the accuracy of familiar identifications corresponded with an increase in the belief that the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.21, SE = 0.10, t = 2.09, p = 0.04), the likelihood the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.25, SE = 0.09, t = 2.75, p = 0.007), and the likelihood the eyewitness’ identification was accurate (B = 0.19, SE = 0.09, t = 2.15, p = 0.031); however, no effect was found for the likelihood of defendant guilt.

Study 3

Studies 1 and 2 revealed that vaguely stating the number of exposures between the eyewitness and defendant prior to the crime was not enough to influence jurors’ judgments. Perhaps the vagueness of the description of familiarity was too subjective to individual mock jurors. Given that the current study stated that the witness was described as seeing and interacting with the defendant once or many times before the commission of the crime, the lack of specificity may be why familiarity was not influential. Therefore, the purpose of Study 3 was to examine whether explicitly stating that the eyewitness had seen the defendant 10 or 20 times prior to the crime was influential. Only one study, to date, has found that a high number of exposures, explicitly stated, influenced jurors’ judgments (e.g., Sheahan et al. 2018). Given that seeing someone 20 times is something that a juror may be able to better conceptualize, rather than a vague sense of familiarity, we predicted that explicitly stating this would be more influential.

Method

Participants

Undergraduate students (N = 179; 63.1% female) were recruited from a psychology participant pool from a university in Eastern Ontario, Canada. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 46 years old (M = 19.87, SD = 3.91). The majority of participants identified as White/Caucasian (66.5%), with a considerable amount identifying as Asian (16.2%) and smaller amounts identifying as Black/African American (7.3%), Latin American (1.7%), Aboriginal-Canadian (2.2%) and those that identified themselves as mixed or other (6.1%). Participants received course credit for their participation.

Design

The design was a 2 (confidence: sure vs. unsure) × 3 (familiarity with the defendant: seen 20 times before with interaction vs. seen 10 times before with interaction vs. never seen before) between-subjects factorial design.

Materials and Procedure

The materials and procedure were identical to that of Study 2 with the exception of the prior interaction between eyewitness and the defendant added in addition to how many times the eyewitness saw the defendant prior to the crime in numerical format.

Results and Discussion

Dichotomous Responses

There were two primary questions of interest: (1) do you think that the defendant is guilty of the murder (yes/no) and (2) do you believe that the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant is accurate (yes/no). Two separate sequential logistic regressions were conducted to determine whether eyewitness confidence and familiarity influenced mock jurors’ dichotomous decisions. When examining whether mock jurors believed the defendant was guilty of the murder, only Model 1, including only the main effects, was significant (χ2(3) = 10.74, p = 0.01). Only a significant effect of confidence emerged (B = 0.92, SE = 0.32, p = 0.004); mock jurors were more likely to believe the defendant was guilty when the eyewitness was confident in her identification. When examining whether mock jurors believed the eyewitness’ identification was accurate, both Models 1 and 2 were significant (χ2(3) = 8.49, p = 0.04 and χ2(5) = 14.65, p = 0.01, respectively). Therefore, Model 2 was retained. There was a significant effect of confidence on mock jurors’ beliefs that his identification was accurate (B = 1.80, SE = 0.60, p = 0.003); mock jurors were more likely to believe the identification was accurate when the eyewitness was confident in her decision. Additionally, there was a significant effect of familiarity (Wald = 5.91, df = 2, p = 0.05). Mock jurors were more likely to believe the identification was accurate when the eyewitness reported seeing the defendant 10 times prior to the crime compared to never (B = 2.86, SE = 1.21, p = 0.02). The remaining effects were not significant; no influence of seeing the defendant 20 times prior to the crime influenced jurors’ judgments.

This omnibus test also produced a significant Confidence × Familiarity interaction (Wald = 6.04, df = 2, p = 0.05). Follow-up analyses revealed that mock jurors were more likely to believe the eyewitness’ identification was accurate when the eyewitness saw the defendant 20 times prior to the crime and was confident in her decision (0.58) compared to not confident in her decision (0.32), χ2(3, N = 65) = 4.34, p = 0.04, Cramer’s v = 0.26). Additionally, when the eyewitness had never seen the defendant prior to the crime, mock jurors were significantly more likely to believe the identification was accurate when the eyewitness reported being confident in her decision (0.63) compared to not confident (0.22) (χ2(1, N = 57) = 9.75, p = 0.002, Cramer’s v = 0.41).

Continuous Responses

There were four primary questions of interest: (1) how likely is it that the defendant is guilty of the murder, (2) do you believe that the defendant is the shooter, (3) how likely is it that the defendant is the shooter, and (4) how likely is it that the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant was accurate. Given that all four dependent variables were significantly correlated (p < 0.001), a MANOVA was conducted to determine whether eyewitness confidence and familiarity influenced mock jurors’ perceptions. Using Wilk’s λ, only a significant multivariate effect of confidence emerged (F(4, 154) = 3.25, p = 0.01, partial η2 = 08). Upon analyzing the univariate effects, the likelihood of guilt (F(1, 157) = 10.97, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.07), the belief that the defendant was the shooter (F(1, 157) = 7.71, p = 0.006, partial η2 = 0.05), the likelihood the defendant was the shooter (F(1, 157) = 9.00, p = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.05), and the likelihood of the eyewitness’ identification of the defendant being accurate (F(1, 157) = 10.46, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.06) all were significant (see Table 3). Mock jurors were more apt to believe that the defendant was guilty and the shooter when the eyewitness’ confidence was high (vs. low). Supporting Studies 1 and 2, when the eyewitness was confident in her decision, mock jurors’ believed there was an increased likelihood that the defendant was the shooter and the eyewitness’ identification was accurate. The remaining effects were not significant.

Perceptions of the Eyewitness

All four questions were significantly correlated (p < 0.001); as such, a composite scale was created (α = 0.82). An ANOVA revealed that there was a significant effect of confidence (F(1, 159) = 60.21, p < 0.001). Mock jurors were more likely to have positive perceptions of the eyewitness when she was confident in her identification (M = 4.88, SD = 1.18) compared to not confident (M = 3.51, SD = 1.13). There also was a significant effect of familiarity (F(1, 159) = 3.04, p = 0.05). Follow-up post hoc analyses revealed that there was no significance; however, there was a trend for eyewitnesses to hold more positive perceptions when the eyewitness had seen the defendant 20 times prior to the crime (M = 4.48, SD = 1.42) compared to both 10 (M = 4.16, SD = 1.28) and zero times (M = 4.06, SD = 1.30).

Perceptions of Familiarity

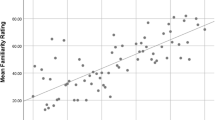

When examining mock jurors’ responses to familiarity in general, 54.2% agreed that witnesses who have seen a person before are more accurate than those who have not seen the person before (M = 4.52, SD = 1.61). A bivariate linear regression was then conducted to determine whether mock jurors’ familiarity perceptions influenced mock jurors’ judgments on all four continuous variables. An increase in mock jurors’ beliefs regarding the accuracy of familiar identifications corresponded with an increase in the likelihood of defendant guilt (B = 0.40, SE = 0.07, t = 5.95, p < 0.001), belief that the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.47, SE = 0.08, t = 6.08, p < 0.001), the likelihood the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.44, SE = 0.07, t = 6.17, p < 0.001), and the likelihood the eyewitness’ identification was accurate (B = 0.46, SE = 0.07, t = 6.53, p < 0.001). We then examined their perceptions of seeing a person many times and 64.8% of mock jurors agreed that witnesses who have seen a person many times are more accurate than those who saw the person only once (M = 4.90, SD = 1.45). An increase in mock jurors’ beliefs regarding the accuracy of familiar identifications corresponded with an increase in the likelihood the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.42, SE = 0.08, t = 5.42, p < 0.001), the belief that the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.44, SE = 0.09, t = 4.91, p < 0.001), the likelihood the defendant was the shooter (B = 0.45, SE = 0.08, t = 5.45, p < 0.001), and the likelihood the eyewitness’ identification was accurate (B = 0.46, SE = 0.08, t = 5.53, p < 0.001).

General Discussion

Given that many cases involve at least one eyewitness being familiar with the defendant in criminal trials (e.g., Flowe et al. 2011), it is important to understand how jurors perceive this shared familiarity between an eyewitness and a defendant. Also, the persuasiveness of eyewitness testimony in the courtroom has been well-established with stranger identifications; however, the persuasiveness of familiar identifications has received far less attention. The current studies are the second in a program of research examining mock jurors’ judgments of familiar identifications where the eyewitness’ confidence also is manipulated. When examining mock jurors’ dichotomous guilt decisions, confidence was the only significant predictor. These findings are not surprising as previous research has consistently found that highly confident eyewitnesses are more influential than non-confident eyewitnesses in stranger identifications, thus providing support that this also extends to familiar identifications. We also wanted to examine whether eyewitness age and/or confidence influenced mock jurors’ judgments in relation to familiarity. The influence of eyewitness age has produced mixed results in the literature, and Study 1 found no effect in accordance with similar research manipulating eyewitness age and familiarity (e.g., Pozzulo et al. 2014; Sheahan et al. 2018), which may suggest that familiarity does not impact jurors’ perceptions differentially across the lifespan. Perhaps these effects are due to the strong role of confidence on jurors’ judgments.

These findings do not explain the null results regarding defendant culpability given that mock jurors generally believed that increased familiarity results in increased accuracy. Across all three studies, a slight majority of mock jurors believed that familiar identifications are more accurate than strange identifications. However, their beliefs did not translate into their judgments in Studies 1 and 2. As mentioned previously, this may be due to the subjective nature in which familiarity was portrayed. Increased exposure was defined as “seen many times”; however, this may mean something different to each individual who took part in this study. Partial support is found for this in Study 3 such that an explicit number of exposures did influence jurors’ judgments. These findings suggest that familiarity between a defendant and an eyewitness needs to be properly defined before mock jurors utilize familiarity in their decision-making. Another potential explanation is that only a slight majority of the sample believed that familiar identifications are more accurate—this could indicate that laypeople do not know a lot about how memory works or that they have an overconfidence in memory abilities (e.g., the idea that “I would remember what happened to me” ).

Interestingly, when the eyewitness had seen the defendant 10 times prior to the crime, mock jurors were more likely to believe the identification was accurate compared to when the eyewitness reported being a stranger to the defendant; however, there was no influence of familiarity at 20 times. These results are similar to those of Vallano et al. (2018) who found that minimal exposure between an alleged perpetrator and eyewitness was more influential to mock jurors than greater exposure. Perhaps jurors may think that 10 times is sufficient to be familiar with an individual and not let other factors hinder their identification of said individual. However, if you see an individual many times mock jurors may perceive this as being too familiar such that an individual may be overconfident in their identification, as can be seen in the case of Joseph Abbitt. Future studies may want to include open-ended questions to ask mock jurors for their reasoning when including evidence of familiar identifications.

When examining the role of familiarity in combination with eyewitness confidence, the current study found a combined influence such that mock jurors were more likely to believe that an identification decision made by an eyewitness was accurate when the eyewitness was described as seeing the defendant 20 times prior to the commission of the crime, and that they were highly confident in their decision. This finding is not surprising, as eyewitness confidence has been found to be highly persuasive to jurors, even when the eyewitness and defendant are described as strangers (e.g., Brewer and Burke 2002). Specifically, mock jurors are likely to believe eyewitness evidence when the eyewitness claims to be very confident in their decision. Additionally, familiarity influenced perceptions of the eyewitness; however, follow-up analyses were not significant but were in the expected direction. Specifically, the more the eyewitness reported seeing the defendant, the more positively she was perceived; as exposure increased, so did perceptions. This suggests that familiarity does, in fact, have the ability to influence mock jurors’ perceptions of the eyewitness which previous research has failed to find (e.g., Pozzulo et al. 2014; Sheahan et al. 2018).

The current program of research also provided some insight into how mock jurors perceive familiarity. For example, approximately half of the participants across all studies (i.e., 54.2% in Study 1; 55.6% in Study 2; 54.2% in Study 3) believed that familiarity between a defendant and an eyewitness would increase identification accuracy compared to identifications made by stranger eyewitnesses. This suggests that approximately half of the participants did not believe that familiarity would increase eyewitness identification accuracy, which may explain why familiarity did not consistently impact mock juror decision-making. It is possible that mock jurors have a misperception about making an identification (e.g., that it would be easy to recognize someone after witnessing a crime). For example, research has found that people tend to be swayed by identifications of suspects compared to other types of lineup decisions (e.g., rejecting the lineup; Wright 2007), which may suggest that a decision from a lineup is enough evidence for mock jurors, and familiarity may not increase the persuasiveness of the eyewitness evidence provided. More research examining familiarity and mock jurors’ reasoning behind their decisions may be useful.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations of this study should be addressed. First is the use of undergraduates. There is some research suggesting that student samples may differ from community samples (e.g., Keller and Wiener 2011). However, a recent meta-analysis found few consistent differences in defendant culpability ratings between the two samples (Bornstein et al. 2017). Future research should extend the current research with a more representative sample of the broader population, perhaps a deliberating mock jury, as research suggests that deliberations may influence verdict decisions (Nuñez et al. 2011).

More pertinent to familiarity itself, jurors’ perceptions of familiar eyewitness identifications are relatively understudied in the literature. As a result, there is not yet a clear or common definition of “familiarity” to use in the current program of research. In fact, familiarity could be reasonably operationalized in a number of different ways (e.g., exposure, type of relationship between the defendant and eyewitness). As a result, the findings from this study cannot be applied to all familiar identification cases, as “familiar” encompasses many different dimensions. As a result, future research should examine other operationalizations of familiarity to better understand its role on mock juror decision-making.

References

Bornstein BH, Deffenbacher KA, Penrod SD, McGorty EK (2012) Effects of exposure time and cognitive operations on facial identification accuracy: a meta-analysis of two variables associated with initial memory strength. Psychol Crime Law 18:473–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/106831X.2010.508458

Bornstein BH, Golding JM, Neuschatz J, Kimbrough C, Reed K, Magyarics C, Luecht K (2017) Mock juror sampling issues in jury simulation research: a meta-analysis. Law Hum Behav 41(1):13–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000223

Brewer N, Burke A (2002) Effects of testimonial inconsistencies and eyewitness confidence on mock-juror judgments. Law Hum Behav 26(3):353–364. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015380522722

Bruce V, Henderson Z, Newman C, Burton AM (2001) Matching identities of familiar and unfamiliar faces caught on CCTV images. J Exp Psychol Appl 7:207–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-898X.7.3.207

Bruer K, Pozzulo JD (2014) Influence of eyewitness age and recall error on mock juror decision-making. Leg Criminol Psychol 19(2):332–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.l2001

Cain WJ, Baker--Ward L, Eaton KL (2005) A face in the crowd: the influences of familiarity and delay on preschoolers’ recognition. Psychol Crime Law 11:315–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160418331294835

Cutler B, Penrod S, Stuve T (1988) Juror decision making in eyewitness identification cases. Law Hum Behav 12:41–55

Devenport J, Penrod S, Cutler B (1997) Eyewitness identification evidence: evaluation commonsense evaluations. Psychol Public Policy Law 3:338–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8971.3.2-3.338

Flowe HD, Mehta A, Ebbeson EB (2011) The role of eyewitness identification evidence in felony case dispositions. Psychol Public Policy Law 17:140–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021311

Goodman GS, Golding JM, Helgeson VS, Haith MM, Michelli J (1987) When a child takes the stand: jurors’ perceptions of children’s eyewitness testimony. Law Hum Behav 11:27–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01044837

Gross J, Hayne H (1996) Eyewitness identification by 5- to 6-year-old children. Law Hum Behav 20:359–373. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129636

Keller SR, Wiener RL (2011) What are we studying? Student jurors, community jurors, and construct validity. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 29:376–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.971

Leippe MR, Romanczyk A, Manion AP (1991) Eyewitness memory for a touching experience: accuracy differences between child and adult witnesses. J Appl Psychol 76:367–379

Lindsay RCL, Lim R, Marando L, Cully D (1986) Mock-juror evaluations of eyewitness testimony: a test of metamemory hypotheses. J Appl Soc Psychol 16:447–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1986.tb01151.x

Mandler G (2008) Familiarity breeds attempts: a critical review of dual-process theories of recognition. Perspect Psychol Sci 3:390–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00087.x

Memon A, Hope L, Bull R (2003) Exposure duration: effects on eyewitness accuracy and confidence. Br J Psychol 94:339–354

Moreland RL, Beach SR (1992) Exposure effects in the classroom: the development of affinity among students. J Exp Soc Psychol 28:244–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(92)90055-O

Moreland RL, Zajonc RB (1982) Exposure effects in person perception: familiarity, similarity, and attraction. J Exp Soc Psychol 18(5):395–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(82)90062-2

Nuñez N, McCrea SM, Culhane SE (2011) Jury decision making research: are researchers focusing on the mouse and not the elephant in the room? Behavioral Sciences and the Law 29:439–451. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.967

Pica E, Sheahan C, Mesesan A & Pozzulo J (2017) The influence of prior familiarity, identification delay, appearance change, and descriptor type on mock jurors’ judgments. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-017-9251-z

Pozzulo JD, Lemieux JMT, Wells E, McCuaig HJ (2006) The influence of eyewitness identification decisions and age of witness on jurors’ verdicts and perceptions of reliability. Psychol Crime Law 12(6):641–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160500415539

Pozzulo JD, Pettalia JL, Bruer K, Javaid S (2014) Eyewitness age and familiarity with the defendant: influential factors in mock jurors’ assessments of defendant guilt? American Journal of Forensic Psychology 32:39–51

Ross DF, Dunning D, Toglia MP, Ceci SJ (1990) The child in the eyes of the jury: assessing mock jurors’ perceptions of the child witness. Law Hum Behav 14:5–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01055786

Sauer JD, Brewer N (2015) Confidence and accuracy of eyewitness identification. In: Valentine T, Davis JP (eds) Wiley series in the psychology of crime, policing and law. Forensic facial identification: theory and practice of identification from eyewitnesses, composites and CCTV. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, pp 185–208

Sheahan CL & Pozzulo JD (under review) “I know that guy!”: familiarity, lineup procedure, and the adolescent witness. Manuscript submitted for publication

Sheahan C, Pozzulo J, Reed J, Pica E (2018) The role of familiarity with the defendant, type of descriptor discrepancy, and eyewitness age on mock jurors’ perceptions of eyewitness testimony. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 33:35–44

Sporer S, Penrod S, Read D, Cutler B (1995) Choosing, confidence, and accuracy: a meta-analysis of the confidence-accuracy relation in eyewitness identification studies. Psychol Bull 118:315–327

The National Registry of Exonerations (2018) Joseph Lamont Abbitt. Retrieved from: https://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/casedetail.aspx?caseid=3807

U.S. Department of Health and Human Sevices (2015) Child maltreatment. Retrieved on December 5, 2018 from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2015.pdf

Vallano J, Pettalia J, Pica E & Pozzulo J (2018) An examination of mock jurors’ judgments in familiar identification cases. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9266-0

Wells G, Olson E (2003) Eyewitness testimony. Annu Rev Psychol 54:277–295. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145028

Wixted JT, Wells GL (2017) The relationship between eyewitness confidence and identification accuracy: a new synthesis. Psychol Sci Public Interest 18:10–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100616686966

Wright DB (2007) The impact of eyewitness identifications from simultaneous and sequential lineups. Memory 15:746–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210701508401

Zajonc RB (1968) Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. J Pers Soc Psychol 9:1–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025848

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pica, E., Sheahan, C.L., Pozzulo, J. et al. The Influence of Familiar and Confident Eyewitnesses on Mock Jurors’ Judgments. J Police Crim Psych 34, 351–361 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9306-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9306-9