Abstract

Elevated atmospheric nitrogen (N) deposition has been detected in many regions of China, but its effects on soil N transformation in temperate forest ecosystems are not well known. We therefore simulated N deposition with four levels of N addition rate (N0, N30, N60, and N120) for 6 years in an old-growth temperate forest in Xiaoxing’an Mountains in Northeastern China. We measured gross N transformation rates in the laboratory using 15N tracing technology to explore the effects of N deposition on soil gross N transformations taking advantage of N deposition soils. No significant differences in gross soil N transformation rates were observed after 6 years of N deposition with various levels of N addition rate. For all N deposition soils, the gross NH4 + immobilization rates were consistently lower than the gross N mineralization rates, leading to net N mineralization. Nitrate (NO3 −) was primarily produced via oxidation of NH4 + (i.e., autotrophic nitrification), whereas oxidation of organic N (i.e., heterotrophic nitrification) was negligible. Differences between the quantity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and ammonia-oxidizing archaea were not significant for any treatment, which likely explains the lack of a significant effect on gross nitrification rates. Gross nitrification rates were much higher than the total NO3 − consumption rates, resulting in a build-up of NO3 −, which highlights the high risk of N losses via NO3 − leaching or gaseous N emissions from soils. This response is opposite that of typical N-limited temperate forests suffering from N deposition, suggesting that the investigated old-growth temperate forest ecosystem is likely to approach N saturation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In most temperate forest ecosystems, nitrogen (N) availability is the main factor limiting forest productivity (Matson et al. 2002; Chen et al. 2004; Zhao et al. 2007). However, due to increasing human activity, including chemical nitrogenous fertilizer production via the Haber–Bosch process and the combustion of fossil fuels (Galloway et al. 2004), the amount of reactive N has rapidly increased worldwide. Atmospheric N deposition is elevated in industrial regions throughout the world and has been accelerating in many developing countries over the last several decades (Fang et al. 2004). Further increases in the deposition of ammonia (NHx) and reactive N oxides (NOX) are projected, which could affect internal soil N cycling and sequestration and subsequent biomass accumulation in forest ecosystems in temperate and boreal zones of Europe and North America (Fan et al. 2007; Brumme and Khanna 2008). For instance, elevated N input decreased gross N mineralization but increased gross nitrification rates in temperate beech and spruce forest soils that experienced considerable N losses (Corre et al. 2003). Results from the NITREX and EXMAN projects indicate that NO3 − leaching from temperate and boreal forests increases when N deposition levels exceed approximately 25 kg ha−1 year−1 and the C/N ratio of the forest floor is less than approximately 25 (Gundersen et al. 1998a, b; MacDonald et al. 2002). In China, elevated NH4 +–N and NO3 −–N concentrations in precipitation have been observed in many cities since the 1980s (Galloway et al. 1987; Li 1984). As a result, temperate forest ecosystems are gradually becoming N-saturated and are switching from a closed to an open N-cycling system, with increasing nitrate leaching and NOx emissions (Aber et al. 1998). Thus, excess Nr is accumulating at the local, regional, and global levels, perhaps leading to negative environmental effects such as deteriorating air quality due to particulate matter as well as increased tropospheric ozone, adverse health effects (Townsend et al. 2003), disrupted forest ecosystem processes (Aber et al. 2003), and the eutrophication and acidification of lakes and streams (Driscoll et al. 2001).

In contrast to studies in temperate zones in industrialized countries, such as European NITREX projects and in Harford Forest (Hofstra and Bouwman 2005), studies quantifying the effects of N deposition on soil N transformations rates and N availability in developing countries have begun later. Thus, the impacts of N deposition on soil N transformations in temperate forest ecosystems in China are not well known (Pu et al. 2001, 2002; Fang et al. 2004). Moreover, field experiments in an old-growth temperate forest site have showed that net primary production (Mao et al. unpublished data) and soil respiration (Gao et al. 2016) were not affected by 6 years of N fertilization, which is different from the general response of temperate forests (Du et al. 2014). Thus, studies are needed to clarify the effects of 6 years of simulated N deposition on gross soil N transformation rates in the old-growth temperate forest in northeastern China, whether the soil is N-limited, and the underlying mechanism of N cycling.

Soil gross N transformation rates measured using 15N tracing techniques could provide a more mechanistic understanding of soil N dynamics than net N transformation rates (Müller et al. 2007; Rütting and Müller 2007; Huygens et al. 2008; Rütting et al. 2008). Thus, the objectives of this study were (1) to measure the gross N transformation rates in a simulated N deposition experiment and (2) to explore the responses of the dynamics of soil gross N transformations to 6 years of simulated atmospheric N deposition in an old-growth temperate forest in northeastern China. The results of this study provide a theoretical basis for appropriately assessing the environmental impacts of N deposition on temperate forest ecosystems in northeastern China.

Materials and methods

Site description

The study site is located in the Liangshui National Reserve of the Xiaoxing’an Mountains in northeastern China (47°10′50″N, 128°53′20″E). The reserve has a typical hilly landscape. The reserve, which had not been harvested or disturbed in any other way since 1952, was established in 1980 and has been part of the China’s Man and the Biosphere Reserve Network since 1997. This reserve was promoted to national nature reserve status with the approval of the Chinese State Council in December 1997 to protect the old-growth mixed broadleaf–Korean pine (Pinus koraiensis) forest ecosystem. This approximately 12,133 ha area is characterized by a rolling mountainous terrain, with elevations ranging from 300 to 707 m a.s.l. with a typical slope of 10°–15° (Qi et al. 2014). The atmospheric N deposition is 12.93 kg N ha−1 year−1 (Song et al. 2017). The soil is classified as dark-brown forest soil according to the Chinese soil classification, which is equivalent to Humaquepts or Cryoboralfs based on American soil taxonomy (Soil Survey Staff 1999). The soil cation exchange capacity is 30.1 cmol kg−1, base saturation is 59%, and the clay (< 10 μm) content is 52%. The mean annual precipitation is 676 mm, with summer precipitation accounting for more than 60% of the total. The relative humidity is 78%, with an annual evaporation of 805 mm. The mean annual temperature is − 0.3 °C, with minimum and maximum monthly average temperatures of − 19.4 °C in January and 20.9 °C in July, respectively. The daily maximum temperature during July and August frequently exceeds 30 °C. The site is covered by snow for 130–150 days, and the frost-free period is 100–120 days per year. The main canopy species include Pinus koraiensis, Picea koraiensis, Abies nephrolepis, Tilia amurensis, T. mandshurica, Acer mono, Fraxinus mandshurica, Ulmus laciniata, Betula costata, B. platyphylla, Quercus mongolica, Larix gmelinii, Juglans mandshurica, Acer ukurunduense, and A. tegmentosum.

To determine the effects of increased N deposition on N transformations in the mixed broadleaf–Korean pine forest, a simulated N deposition field experiment was initiated in 2008. Twelve plots (20 × 20 m) were established at 10-m intervals to prevent disturbance among plots. The site factors were considered in site selection to minimize any confounding effects on the responses of forest ecosystems to chronic N deposition (Lovett and Rueth 1999; Goodale and Aber 2001). All woody stems > 2 cm diameter at breast height in the plot were mapped, measured, identified to species, and tagged in 2008. Four levels of N addition treatment were established in triplicate (N0, N30, N60, and N120) by applying CO(NH2)2 solution at a rate of 0, 30, 60, and 120 kg N ha−1 a−1, respectively, with the N0 treatment receiving an equal amount of water. The solution was applied at the beginning of June, July, and August each year (since June 2008) using an equal split application.

In November 2014, three soil subsamples were taken from the A horizon (0–20 cm) of each plot, pooled together, passed through a 2 mm sieve, homogenized, and split into two subsamples. One subsample was stored at 4 °C for < 1 month before the experiment, and the other was air-dried for soil property analysis.

15N tracing experiment

Two 15N-labelled treatments (three replicates each) were established. Nitrogen was applied as 15NH4NO3 or NH 154 NO3 at 10.22 and 10.19 atom % 15N excess, respectively. For each soil sample, 30 Erlenmeyer flasks (250 mL) were prepared with 20 g (oven-dry basis) fresh soil. The soils (in sealed flasks) were pre-incubated in the dark at 25 °C for 24 h. After pre-incubation, 2.2 mL of 15NH4NO3 solution was added to 15 Erlenmeyer flasks and 2.2 mL of NH 154 –NO3 solution was added to the other 15 Erlenmeyer flasks at a rate of 20 mg NH4 +–N g−1 soil and 20 mg NO3 −–N g−1 soil, respectively. The 15N-labelled solutions were pipetted evenly over the soil surface, and the final soil moisture content was adjusted to 60% water-holding capacity with deionized water. The flasks were then sealed with plastic film containing small holes to permit gas exchange and incubated in the dark at 25 °C for 96 h.

The 15NH4NO3- and NH 154 NO3-labelled flasks were extracted with 2 M KCl solution (at a soil to KCl solution ratio of 1:5 m/v) at 0.5, 48, and 96 h of incubation. After the samples were shaken at 250 rpm on a mechanical shaker in the dark at 25 °C for 1 h, they were filtered through Whatman No. 42 filter papers. The extraction was used to determine the concentrations and isotopic compositions of NH4 + and NO3 −.

15N-tracing model

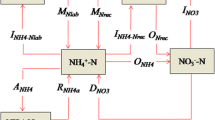

The 15N-tracing data were analyzed using the Ntrace model (Müller et al. 2007), a process-based 15N-tracing model (Fig. 1). Ten gross N transformation rates were quantified with this model: M Nrec, mineralization of recalcitrant organic N to NH4 +; M Nlab, mineralization of labile organic-N to NH4 +; I NH4_Nlab, immobilization of NH4 + to labile organic N; I NH4_Nrec, immobilization of NH4 + to recalcitrant organic N; R NH4ads, release of adsorbed NH4 +; A NH4, adsorption of NH4 + on cation exchange sites; O NH4, oxidation of NH4 + to NO3 − (autotrophic nitrification); O Nrec, oxidation of recalcitrant organic N to NO3 − (heterotrophic nitrification); I NO3, immobilization of NO3 − to recalcitrant organic N; and D NO3, dissimilatory NO3 − reduction to NH4 + (DNRA; Müller et al. 2007). The main N transformations considered in the model included the following: mineralization (M = M Nrec + M Nlab), nitrification (N = O NH4_+ O Nrec), and immobilization of NH4 + (I NH4) and NO3 − (I NO3).

15N-tracing model used for data analysis. M Nrec, mineralization of recalcitrant organic N to NH4 +; M Nlab, mineralization of labile organic-N to NH4 +; I NH4_Nlab, immobilization of NH4 + to labile organic N; I NH4_Nrec, immobilization of NH4 + to recalcitrant organic N; R NH4ads, release of adsorbed NH4 +; A NH4, adsorption of NH4 + on cation exchange sites; O NH4, oxidation of NH4 + to NO3 − (autotrophic nitrification); O Nrec, oxidation of recalcitrant organic N to NO3 − (heterotrophic nitrification); I NO3, immobilization of NO3 − to recalcitrant organic N; and D NO3, dissimilatory NO3 − reduction to NH4 + (DNRA)

The transformation rates were calculated using zero-order, first-order, or Michaelis–Menten kinetics. To identify the most appropriate model that best described the measured N dynamics, we tested several model modifications, varying in the number of N transformations, kinetic settings, and N pools (Rütting et al. 2008). The final model was selected according to Akaike’s information criterion (AIC; Cox et al. 2006). Parameter optimization was carried out with the Metropolis algorithm (MCMC-MA). The steps used in model development and the optimization algorithm were described in detail by Müller et al. (2007). The misfit function between the simulation output and observations, f(m) (see Eq. 3 of Müller et al. (2007)), takes into account the variance of the individual observations. Analyses using this parameter optimization concept in previous studies have shown that the mineralization of two conceptual organic N pools produce realistic NH4 + dynamics (Huygens et al. 2007; Müller et al. 2009). The MCMC-MA routine was set up in the MATLAB software package (Version 7.2, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA), which calls models that are separately set up in Simulink (Version 6.4). Initial concentrations of the mineral N pools (14N and 15N pool size) were determined according to Müller et al. (2004). Briefly, NH4 + and NO3 − concentrations were estimated for time zero by back-extrapolation of data at t = 0.5 h and t = 48 h. The difference between NH4 + applied and NH4 + determined was considered to represent NH4 + that was immediately adsorbed on NH4 + exchange sites (NH4ads) (Zhang et al. 2011).

Data supplied to the model were the concentrations and 15N excess values (mean ± SD) of NH4 + and NO3 − from the two 15N treatments.

Analyses

Soil properties were determined following the Soil Agro-Chemical Analysis procedures of Lu (2000). Soil pH was measured in a 1:2.5 (v/v) soil to water ratio using a DMP-2 mV/pH detector (Quark, Nanjing, China). Soil organic carbon (SOC) was analyzed by wet digestion using H2SO4–K2Cr2O7, and total N (TN) was determined by semi-micro Kjeldahl digestion using Se, CuSO4, and K2SO4 as catalysts (Lu 2000). NH4 + and NO3 − were extracted using 2 M KCl at a soil to solution ratio of 1:5 (m/v) on a mechanical shaker for 60 min at 250 rpm at 25 °C. The extract was filtered through qualitative filter paper, and the NH4 + and NO3 − concentrations were determined using a continuous-flow analyzer (Skalar, Breda, Netherlands). Isotopic compositions of NH4 + and NO3 − were determined using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (SerCon 20–22; Europa Scientific Integra, Crewe, UK). The abundances of AOA and AOB communities were determined by reverse-transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR).

Calculation

Two net transformation rates used in this literature can be determined using the following equations:

where M net and N net are the net N mineralization rate and the net NO3 − nitrification rate, respectively; M, N, I NH4, I NO3, and D NO3 are the gross NH4 + mineralization rate, the gross NO3 − nitrification rate, the gross NH4 + immobilization rate, the gross NO3 − immobilization rate, and the rate of dissimilatory NO3 − reduction to NH4 +, respectively. The mean residence time (MRT) of the NH4 + pool was calculated using the following equation:

where NH4 + pool is the NH4 + pool size and M is the gross mineralization rate. The MRT indicates the mean length of time in which an N atom resides in a given pool. A lower MRT indicates a faster turnover rate and hence a more dynamic pool (Hart et al. 1994).

Statistical analyses and model setup

The optimization procedure resulted in a probability density function for each parameter, from which parameter means and standard deviations were calculated (Müller et al. 2007). Each run of the analysis was carried out with three parallel sequences to identify adequate iteration numbers. Based on the kinetic settings and the final parameters, average N transformation rates were calculated over the entire period, which were expressed in units of mg N kg−1 soil day−1.

Differences in soil properties and gross N transformation rates among different soil treatments were assessed with one-way ANOVA and compared with a LSD test at P = 0.05. Pearson’s correlation analysis was applied to correlate edaphic variables with gross N transformation rates using SPSS software version 18.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Multiple stepwise regression analyses were applied to determine whether the soil variables (i.e., soil organic C, total N, C/N ratio, pH, initial NH4 +–N, and NO3 −–N concentrations) were significantly related to the gross N transformation rates.

Results

Soil properties after 6 years of N deposition

Six years of elevated N addition did not have a significant effect on any of the measured soil properties (i.e., pH, TN, SOC, and NO3 – concentrations) except NH4 + concentration, which was significantly higher under N120 treatment than under N30 treatment. All soils were weakly acidic, with pH values ranging from 5.5 to 5.7 (Table 1). The soil organic C contents were extreme high, ranging from 113.2 to 87.7 g C kg−1. Total N contents varied from 10.5 to 7.9 g N kg−1. The C/N ratios were relatively low, ranging from 10.8 to 12.0 in the four treatment groups. The inorganic N was dominated by NO3 −, which was one order of magnitude higher than NH4 + concentrations for all treatments. The NH4 + and NO3 − concentrations ranged from 1.6 to 1.1 mg N kg−1 and 33.0 to 13.7 mg N kg−1, respectively.

NH4 + and NO3 − concentrations and 15 N enrichment during incubation

The increased concentrations and isotopic enrichments were generally within the range of the observed mean ± SD. In all soils, ammonium concentrations generally decreased with incubation time, whereas nitrate concentrations increased, indicating that net nitrification had occurred.

The 15N abundance of the NH4 + pool declined in all soils when the pool was labelled, indicating a dilution of NH4 + under natural or low 15N enrichment conditions. By contrast, the 15N abundance of the NO3 − pool increased when NH4 + was labelled, indicating a transfer of NH4 + into the NO3 − pool. Similarly, the decline in 15N abundance of the NO3 − pool in the 15NO3 −-labelled treatment indicated that NO3 − entered this pool under natural or low 15N enrichment conditions. The 15N abundance of the NH4 + pool remained more or less unchanged, indicating that remineralization of immobilized NO3 − or DNRA was negligible.

Gross N transformation

No significant differences in gross soil N transformation rates were observed among any treatment after 6 years of simulated N deposition in the field (Figs. 2, 3). For all treatments, the gross NH4 + immobilization rates were consistently lower than the gross N mineralization rates, resulting in net N mineralization, which was also not significantly different among treatments (Fig. 2). In addition, the mean residence time (MRT) of the NH4 + pool did not significantly differ among the four treatments, ranging from 0.21 to 0.28 d. The gross N mineralization rates were strongly positively correlated with the gross NH4 + immobilization rates (P < 0.01; Fig. 4a). However, neither gross N mineralization rates nor gross NH4 + immobilization rates were significantly correlated with soil organic C (SOC), total N (TN), or C/N ratio.

NO3 − was primarily produced via oxidation of NH4 + (i.e., autotrophic nitrification), whereas oxidation of organic N (i.e., heterotrophic nitrification) was negligible. There were some changes in gross nitrification rates among different treatments, but they were not statistically significant, mainly due to large spatial variability. In all treatments, the rates of NO3 − immobilization and dissimilatory NO3 − reduction to NH4 + (DNRA) were near zero.

The gross nitrification rates were much higher than the NO3 − immobilization rates, DNRA, or total NO3 − consumption (the sum of NO3 − immobilization and DNRA) in all treatments, resulting in substantial net NO3 − production. Thus, the risk of NO3 − loss was high in all of the studied soils (Fig. 3). The gross nitrification rates were strongly negatively correlated with gross NH4 + immobilization rates (P < 0.01; Fig. 4b). Meanwhile, there was no significant relationship between gross NO3 − immobilization rate and C/N ratio.

Soil AOB and AOA abundance

The differences in ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) abundances were not significant among N deposition treatments (Fig. 5). Moreover, there was no difference in the ratios of archaeal to bacterial amoA gene copy numbers among treatments, which ranged from 1.16 to 1.13.

Discussion

Soil N transformations occur simultaneously and interact with each other; thus, the response of transformations to N deposition and fertilization is complex (Gao et al. 2015). In addition to the amounts and forms of N deposition and fertilization, soil N transformations are also affected by many factors, such as pH, SOC, TN, and OXC (oxidation capacity), as well as AOA and AOB abundances (Corre et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2009). This complexity makes it difficult to identify the main characteristics, controls, and mechanisms regulating changes in transformations induced by N deposition or fertilization, which explains why we have an incomplete understanding of the relationships between N enrichment, N loss, and soil acidification in response to N deposition and fertilization (Templer et al. 2008; Zhao et al. 2007).

Gross N mineralization and NH4 + immobilization rates

In general, N addition to N-limited ecosystems can stimulate N mineralization by removing microbial N limitation, mainly by reducing C/N ratios. However, in the present study, N addition had no significant effect on gross N mineralization after 6 years of N deposition in the field, which is in line with the results obtained in a boreal forest at the southern edge of the AOSR, Alberta (Cheng et al. 2011) and in the Catskill Mountains (Christenson et al. 2009). The plots in the Catskill Mountains (Christenson et al. 2009) and in southern Canada (Cheng et al. 2011) had been fertilized for 3.5 and 4 years, respectively, and had received cumulative amounts of N addition equivalent to 187.5 and 120 kg N ha−1, respectively. By contrast, both the duration (6 years) and cumulative amounts of N (180, 360, and 720 kg N ha−1, for N30, N60, N120 treatment, respectively) applied to our sites in the current study nearly exceeded those used in the previous studies. The explanations for the lack of a response to N fertilization in a N-limited ecosystem proposed in the previous studies were that either the amount of N added was insufficient to cause a significant response or that there was a lag between the time of N application and the onset of changes to soil N transformation rates (Cheng et al. 2011).

In the present study, the gross NH4 + immobilization rates (I NH4) were consistently lower than the gross N mineralization rates, resulting in the flow of large amounts of mineral N to the nitrification process (Fig. 2), which is in contrast to the typical response in temperate forests (Corre et al. 2003), as NH4 + immobilization rates are comparable to gross N mineralization rates. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that the main fate for deposited and added N in forest soils is microbial N immobilization, especially under N limited conditions (Bengtsson and Bergwall 2000; Templer et al. 2005; Zogg et al. 2000). Hodge et al. (2000) and Schimel and Bennett (2004) suggested that added N added in soils only promotes the net release of NH4 + and autotrophic nitrification if the microbial N limitation is removed. Taken together, our results of soil gross N transformations suggest that the old-growth temperate forest ecosystem in northeastern China is not N-limited but is likely approaching N saturation.

Gross nitrification and NO3 − immobilization rates

The gross nitrification rates were much higher than the total NO3 − consumption rates in all treatments, resulting in a net production of nitrate. This result is in line with the observation that inorganic N was dominated by NO3 − in the studied soils, which led to a high risk of NO3 − loss. According to the nutrient retention hypothesis proposed by Vitousek and Reiners (1975), mineral N production in native ecosystems is generally low to curtail excessive N loss. A low rate of nitrification can minimize NO3 − losses (Vitousek et al. 1979). Stark and Hart (1997) reported that the coupling between high nitrification rates and high NO3 − immobilization rates represents another N conservation mechanism in undisturbed coniferous forest soils in New Mexico and Oregon. Our results, which were obtained from an old-growth temperate forest ecosystem, are not consistent with the findings of Vitousek and Reiners (1975) and Stark and Hart (1997).

Soil pH is an important factor that may affect autotrophic nitrification. Microbiological oxidation of NH4 + to NO3 – does not occur in soils with pH < 4.5 (Weber and Gainey 1962), despite recent investigations suggesting that ammonia-oxidizing archaea could drive the oxidation of NH4 + to NO3 – (Lu et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2012). In general, the autotrophic nitrification rate increases with increasing soil pH (Cheng et al., 2013; Zhang et al. 2013). Since the soil pH values in the current study were > 5.5, autotrophic nitrification would not have been impeded by pH. Soil C/N ratios are another factor affecting soil N conservation. Results from the NITREX and EXMAN projects indicate that NO3 − leaching from temperate and boreal forests can increase if the C/N ratio falls below 25 (Dise et al. 1998; Gundersen et al. 1998b; MacDonald et al. 2002). The C/N ratio of the temperate forest soils investigated in the current study was much < 25 (ranging from 10.8 to 12.0), also supporting the notion that the risk of NO3 − leaching was high. However, the mechanisms governing microbial processes are currently unclear. Further studies are needed to explore the underlying mechanism of gross N transformations in the climax forest ecosystem in northeastern China.

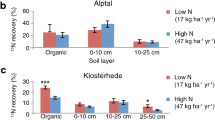

Many previous studies have found that N addition increases gross nitrification rates and subsequently increases NO3 − leaching in temperate forest soils (Tietema 1998; Venterea et al. 2003). However, the rates of nitrification (net and gross nitrification) and NO3 − consumption (gross NO3 − immobilization + DNRA) in the forest soils investigated in the current study showed no significant responses to N fertilization, in agreement with the findings of Aber et al. (1998), Corre et al. (2007), and Cheng et al. (2011). Some studies have suggested that N deposition and fertilization could affect soil NO3 − production pathways. For example, Jordan et al. (2005) found that nitrification in the organic and 0–10 cm mineral soil layer was dominated by heterotrophic nitrification in two acidic forest soils that received a high rate of N deposition. However, Wertz et al. (2012) reported that autotrophic nitrification still primarily contributed (55–97%) to nitrification in N-amended organic and mineral soils in logged pine and spruce stands. Our results indicate that NO3 − was primarily produced via autotrophic nitrification, which was little affected by 6 years of simulated N depositions. The abundances of AOA and AOB and the ratio of AOA to AOB gene copy number were also not significantly altered by 6 years of simulated N deposition (Fig. 5), which might be the main reason that our 6-year simulated N deposition treatment had little effect on nitrification rates. Therefore, the risk of NO3 − loss from this boreal forest soil is considerable.

Aber et al. (1998) defined four stages of N saturation in forest ecosystems (stages 0–3). In stages 0 and 1, primary production is limited by N supply in most forest ecosystems, and the systems are efficient at retaining atmospheric N input. In stage 2, net primary productivity (NPP) starts to decrease, mainly due to the suppression of humus-degrading enzymes and the alteration in chemical bond structures in soil organic matter. Gross N mineralization, gross nitrification, and the risk of NO3 − loss increase sharply at this stage. In the present study, gross N mineralization and NH4 + immobilization were not found to be tightly coupled in temperate forest soils. Soil microbial N cycling, characterized by low N immobilization associated with high gross N mineralization and nitrification in N-deposited and N-fertilized forest sites, is a sign of uncoupled soil N cycling (Corre et al. 2003; Tietema 1998). Additionally, an experiment at the current experimental site showed that net primary production (Mao et al. unpublished data) and soil respiration (Gao et al. 2016) were not affected by 6 years of N fertilization. Therefore, the soil features in response to N deposition observed in our study are indicative of stage 2. In addition, Zhang et al. (2016) found that the NO3 − to NH4 + ratio was as high as 8 and that NO3 − became the dominant N form in stream water at the same study site. These values are significantly higher than the values obtained in sites with lower soil nitrification rates. These findings, together with the current results, suggest that (1) the amount of external N fertilizer utilized by our studied soil was negligible, and most was probably lost by leaching or NOX emissions, and (2) our studied soil was likely approaching N saturation.

Conclusions

The results show that N addition had no significant effect on soil gross N transformations after 6 years of N fertilization in the field. The gross NH4 + immobilization rates and gross NO3 − consumption rates were consistently lower than the gross N mineralization rates and gross nitrification rates, respectively, for all treatments, indicating that the risk of NO3 − loss was probably high in the investigated soils. Additionally, N fertilization had no significant effects on gross soil N transformations, NPP, or soil respiration, suggesting that the old-growth temperate forest ecosystem in northeastern China is likely approaching N saturation. Further studies should be conducted to explore the underlying mechanism of soil N cycling in this climax forest ecosystem in northeastern China.

References

Aber JD, McDowell W, Nadelhoffer KJ, Magill A, Berntson G, Kamakea M, McNulty SG, Currie W (1998) Nitrogen saturation in temperate forest ecosystems, hypotheses revisited. Bioscience 48(11):921–934

Aber JD, Goodale CL, Ollinger SV, Smith ML, Magill AH, Martin ME, Hallett RA, Stoddard JL (2003) Is nitrogen deposition altering the nitrogen status of northeastern forests? Bioscience 53(4):375–389

Bengtsson G, Bergwall C (2000) Fate of 15 N labelled nitrate and ammonium in a fertilized forest soil. Soil Biol Biochem 32(4):545–557

Brumme R, Khanna PK (2008) Ecological and site historical aspects of N dynamics and current N status in temperate forests. Glob Change Biol 14(1):125–141

Chen XY, Mulder J, Wang YH, Zhao DW, Xiang RJ (2004) Atmospheric deposition, mineralization and leaching of nitrogen in subtropical forested catchments, South China. Environ Geochem Health 26(2):179–186

Cheng Y, Cai ZC, Zhang JB, Scott XC (2011) Gross N transformations were little affected by 4 years of simulated N and S depositions in an aspen-white spruce dominated boreal forest in Alberta, Canada. For Ecol Manag 262(3):571–578

Cheng Y, Wang J, Mary B, Zhang JB, Cai ZC, Chang SX (2013) Soil pH has contrasting effects on gross and net nitrogen mineralizations in adjacent forest and grassland soils in central Alberta, Canada. Soil Biol Biochem 57:848–857

Christenson LM, Lovett GM, Weathers KC, Arthur MA (2009) The influence of tree species, nitrogen fertilization, and soil C to N ratio on gross soil nitrogen transformations. Soil Sci Soc Am J 73(2):638–648

Corre MD, Beese FO, Brumme R (2003) Soil nitrogen cycle in high nitrogen deposition forest: changes under nitrogen saturation and liming. Ecol Appl 13(2):287–298

Corre MD, Brumme R, Veldkamp E, Beese FO (2007) Changes in nitrogen cycling and retention processes in soils under spruce forests along a nitrogen enrichment gradient in Germany. Glob Change Biol 13(7):1509–1527

Cox GM, Gibbons JM, Wood ATA, Craigon J, Ramsden SJ, Crout NMJ (2006) Towards the systematic simplification of mechanistic models. Ecol Model 198(1):240–246

Dise NB, Matzner E, Forsius M (1998) Evaluation of organic horizon C:N ratio as an indicator of nitrate leaching in conifer forests across Europe. Environ Pollut 102(1):453–456

Driscoll CT, Lawrence GB, Bulger AJ, Butler TJ, Cronan CS, Eagar C, Lambert KF, Likens GE, Stoddard JL, Weathers KC (2001) Acidic deposition in the northeastern United States: sources and inputs, ecosystem effects, and management strategies. Bioscience 51(3):180–198

Du ZH, Wang W, Zeng WJ, Zeng H (2014) Nitrogen deposition enhances carbon sequestration by plantations in northern China. PLoS ONE 9(2):e87975

Fan HB, Huang YZ, Yuan YH, Li YY, Huang RZ, Fan HY (2007) Carbon cycling of forest ecosystems in response to global nitrogen deposition: a review. Acta Ecol Sin 27(7):2997–3009

Fang YT, Mo JM, Gundersen P, Zhou GY, Li DJ (2004) Nitrogen transformations in forest soils and its responses to atmospheric nitrogen deposition: a review. Acta Ecol Sin 24(7):1523–1531

Galloway JN, Dianwu Z, Jiling X, Likens GE (1987) Acid rain: China, United States, and a remote area. Science 236(4808):1559–1562

Galloway JN, Dentener DG, Capone EW (2004) Nitrogen cycles: past, present and future. Biogeochemistry 70(2):153–226

Gao WL, Yang H, Kou L, Li SG (2015) Effects of nitrogen deposition and fertilization on N transformations in forest soils: a review. J Soil Sediments 15(4):863–879

Gao WF, Shi BK, Jin GZ (2016) Effect of simulated nitrogen deposition on soil respiration in the typical mixed broadleaved Korean pine forest. J Nanjing For Univ 40(1):8–14

Goodale CL, Aber JD (2001) The long-term effects of land-use history on nitrogen cycling in northern hardwood forests. Ecol Appl 11(1):253–267

Gundersen P, Callesen I, Vries WD (1998a) Nitrate leaching in forest ecosystems is related to forest floor C/N ratios. Environ Pollut 102(1):403–407

Gundersen P, Emmett BA, Kjonaas OJ, Koopmans CJ, Tietema A (1998b) Impact of nitrogen deposition on nitrogen cycling in forests: a synthesis of NITREX data. For Ecol Manag 101(1):37–55

Hart SC, Nason GE, Myrold DD, Perry DA (1994) Dynamics of gross nitrogen transformations in an old-growth forest: the carbon connection. Ecology 75(4):880–891

Hodge A, Robinson D, Fitter A (2000) Are microorganisms more effective than plants at competing for nitrogen? Trends Plant Sci 5(7):304–308

Hofstra N, Bouwman AF (2005) Denitrification in agricultural soils: summarizing published data and estimating global annual rates. Nutr Cycl Agroecosys 72(3):267–278

Huygens D, Rütting T, Boeckx P, Cleemput OV, Godoy R, Müller C (2007) Soil nitrogen conservation mechanisms in a pristine south Chilean Nothofagusforest ecosystem. Soil Biol Biochem 39(10):2448–2458

Huygens D, Boeckx P, Templer P, Paulino L, Cleemput OV, Oyarzún C, Müller C, Godoy R (2008) Mechanisms for retention of bioavailable nitrogen in volcanic rainforest soils. Nat Geosci 1(8):543–548

Jordan FL, Cantera JJL, Fenn ME, Stein LY (2005) Autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria contribute minimally to nitrification in a nitrogen-impacted forested ecosystem. Appl Environ Microbiol 71(1):197–206

Li HZ (1984) Analysis of the precipitation acidity of selected areas in China. Chinese Academy of Meteorology, Beijing

Lovett GM, Rueth H (1999) Soil nitrogen transformations in beech and maple stands along a nitrogen deposition gradient. Ecol Appl 9(4):1330–1344

Lu RK (2000) Soil agro-chemical analyses. Agricultural Technical Press of China, Beijing

Lu L, Han WY, Zhang JB, Wu YC, Wang BZ, Lin XG, Zhu JG, Cai ZC, Jia ZJ (2012) Nitrification of archaeal ammonia oxidizers in acid soils is supported by hydrolysis of urea. ISME J 6(10):1978–1984

MacDonald JA, Dise NB, Matzner E, Armbruster M, Gundersen P, Forsius M (2002) Nitrogen input together with ecosystem nitrogen enrichment predict nitrate leaching from European forests. Glob Change Biol 8(10):1028–1033

Matson P, Lohse KA, Hall SJ (2002) The globalization of nitrogen deposition: consequences for terrestrial ecosystems. Ambio 31(2):113–119

Müller C, Stevens RJ, Laughlin RJ (2004) A 15 N tracing model to analyse N transformations in old grassland soil. Soil Biol Biochem 36(4):619–632

Müller C, Rütting T, Kattge J, Laughlin RJ, Stevens RJ (2007) Estimation of parameters in complex 15 N tracing models via Monte Carlo sampling. Soil Biol Biochem 39(3):715–726

Müller C, Rütting T, Abbasi MK, Laughlin RJ, Kammann C, Clough TJ, Sherlock RR, Kattge J, Jäger HJ, Watson CJ, Stevens RJ (2009) Effect of elevated CO2 on soil N dynamics in a temperate grassland soil. Soil Biol Biochem 41(9):1996–2001

Pu GX, Saffigna PG, Xu ZH (2001) Denitrification, leaching and immobilisation of 15 N-labelled nitrate in winter under windrowed harvesting residues in hoop pine plantations of 1–3 years old in subtropical Australia. For Ecol Manag 152(1):183–194

Pu GX, Xu ZH, Saffigna PG (2002) Fate of 15 N-labelled nitrate in a wet summer under different residue management regimes in young hoop pine plantations. For Ecol Manag 170(1):285–298

Qi YJ, Li FR, Liu ZL, Jin GZ (2014) Impact of understorey on overstorey leaf area index estimation from optical remote sensing in five forest types in northeastern China. Agric For Meteorol 198:72–80

Rütting T, Müller C (2007) 15 N tracing models with a Monte Carlo optimization procedure provide new insights on gross N transformations in soils. Soil Biol Biochem 39(9):2351–2361

Rütting T, Huygens D, Müller C, Cleemput OV, Godoy R, Boeckx P (2008) Functional role of DNRA and nitrite reduction in a pristine south Chilean Nothofagus forest. Biogeochemistry 90(3):243–258

Schimel JP, Bennett J (2004) Nitrogen mineralization: challenges of a changing paradigm. Ecology 85(3):591–602

Soil Survey Staff (1999) Soil taxonomy: A basic system of soil classification for making and interpreting soil surveys. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Washington

Song L, Tian P, Zhang JB, Jin GZ (2017) Effects of 3 years of simulated nitrogen deposition on soil nitrogen dynamics and greenhouse gas emissions in a Korean pine plantation of northeast China. Sci Total Environ 609:1303–1311

Stark JM, Hart SC (1997) High rates of nitrification and nitrate turnover in undisturbed coniferous forests. Nature 385(6611):61–64

Templer PH, Lovett GM, Weathers KC, Findlay SE, Dawson TE (2005) Influence of tree species on forest nitrogen retention in the Catskill Mountains, New York, USA. Ecosystems 8(1):1–16

Templer PH, Silver WL, Pett-Ridge J, DeAngelis KM, Firestone MK (2008) Plant and microbial controls on nitrogen retention and loss in a humid tropical forest. Ecology 89(11):3030–3040

Tietema A (1998) Microbial carbon and nitrogen dynamics in coniferous forest floor material collected along a European nitrogen deposition gradient. For Ecol Manag 101(1):29–36

Townsend AR, Howarth RW, Bazzaz FA, Booth MS, Cleveland CC, Collinge SK, Dobson AP, Epstein PR, Holland EA, Keeney DR, Mallin MA, Rogers CA, Wayne P, Wolfe AH (2003) Human health effects of a changing global nitrogen cycle. Front Ecol Environ 1(5):240–246

Venterea R, Groffman P, Verchot L, Magill A, Aber J, Steudler P (2003) Nitrogen oxide gas emissions from temperate forest soils receiving long-term nitrogen inputs. Glob Change Biol 9(3):346–357

Vitousek PM, Reiners WA (1975) Ecosystem succession and nutrient retention: a hypothesis. Bioscience 25(6):376–381

Vitousek PM, Gosz JR, Grier CC, Melillo JM, Reiners WA, Todd RL (1979) Nitrate losses from disturbed ecosystems. Science 204(4392):469–474

Weber DF, Gainey PL (1962) Relative sensitivity of nitrifying organisms to hydrogen ions in soils and solutions. Soil Sci 94(3):138–145

Wertz S, Leigh AKK, Grayston SJ (2012) Effects of long-term fertilization of forest soils on potential nitrification and on the abundance and community structure of ammonia oxidizers and nitrite oxidizers. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 79(1):142–154

Xu YB, Xu ZH, Cai ZC, Reverchon F (2013) Review of denitrification in tropical and subtropical soils of terrestrial ecosystems. J Soil Sediments 13(4):699–710

Zhang JB, Cai ZC, Cheng Y, Zhu TB (2009) Denitrification and total nitrogen gas production from forest soils of Eastern China. Soil Biol Biochem 41(12):2551–2557

Zhang JB, Cai ZC, Zhu TB (2011) N2O production pathways in the subtropical acid forest soils in China. Environ Res 111(5):643–649

Zhang LM, Hu HW, Shen JP, He JZ (2012) Ammonia-oxidizing archaea have more important role than ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in ammonia oxidation of strongly acidic soils. ISME J 6(5):1032–1045

Zhang JB, Cai ZC, Zhu TB, Yang WY, Müller C (2013) Mechanisms for the retention of inorganic N in acidic forest soils of southern China. Sci Rep 3(2342):1–8

Zhang JB, Tian P, Tang JL, Yuan L, Ke Y, Cai ZC, Zhu B, Müller C (2016) The characteristics of soil N transformations regulate the composition of hydrologic N export from terrestrial ecosystem. J Geophys Res Biogeosci 121(6):1–11

Zhao W, Cai ZC, Xu ZH (2007) Does ammonium-based N addition influence nitrification and acidification in humid subtropical soils of China? Plant Soil 297(1–2):213–221

Zogg GP, Zak DR, Pregitzer KS, Burton AJ (2000) Microbial immobilization and the retention of anthropogenic nitrate in a northern hardwood forest. Ecology 81(7):1858–1866

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Project funding: This work was supported by Grants from the “973” Project (2014CB953803), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2572017EA02), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD, 164320H116).

The online version is available at http://www.springerlink.com

Corresponding editor: Chai Ruihai.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, P., Zhang, J., Müller, C. et al. Effects of six years of simulated N deposition on gross soil N transformation rates in an old-growth temperate forest. J. For. Res. 29, 647–656 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-017-0484-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-017-0484-6