Abstract

Background

In recent years, organizational leaders have faced growing pressure to respond to social and political issues. Although previous research has examined the experiences of corporate CEOs engaging in these issues, less is known about the perspectives of healthcare leaders.

Objective

To explore the experiences of healthcare CEOs engaging in health-related social and political issues, with a specific focus on systemic racism and abortion policy.

Design

Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews from February to July 2023.

Participants

CEOs of US-based hospitals or health systems.

Approach

One-on-one interviews which were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, and analyzed using thematic analysis.

Key Results

This study included 25 CEOs of US-based hospitals or health systems. Almost half were between ages 60 and 69 (12 [48%]), 19 identified as male (76%), and 20 identified as White (80%). Approximately half self-identified as Democrats (13 [55%]). Most hospitals and health systems were private non-profits (15 [60%]). The interviews organized around four domains: (1) Perspectives on their Role, (2) Factors Impacting Engagement, (3) Improving Engagement, and (4) Experiences Responding to Recent Polarizing Events. Within these four domains, nine themes emerged. CEOs described increasing pressure to engage and had mixed feelings about their role. They identified personal, organizational, and political factors that affect their engagement. CEOs identified strategies to measure the success of their engagement and also reflected on their experiences speaking out about systemic racism and abortion legislation.

Conclusions

In this qualitative study, healthcare CEOs described mixed perspectives on their role engaging in social and political issues and identified several factors impacting engagement. CEOs cited few strategies to measure the success of their engagement. Given that healthcare leaders are increasingly asked to address policy debates, more work is needed to examine the role and impact of healthcare CEOs engaging in health-related social and political issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Chief executive officers (CEOs) are increasingly expected to take public stances on sensitive social and political issues, engaging in what is now commonly called “CEO Activism.”1 CEOs have made statements on various polarizing issues in recent years, including immigration policy, gun control, abortion restrictions, climate change, voting, and LGBTQIA + rights. They play an essential role in defining an organization’s mission and helping guide community engagement and investment, and their activism influences employee perceptions and commitment to the company.2,3,4,5,6,7,8 While research has examined the experiences, perspectives, and approaches to social responsibility among corporate CEOs, less is known about healthcare CEOs.

Their perspectives are important for several reasons. First, as the largest US employer, healthcare CEOs employ over 20 million people and hold considerable power and influence.9 Second, many leading social, environmental, political, and ethical issues directly relate to health and health disparities. Because healthcare CEOs lead organizations dedicated to improving the health and well-being of their communities, these issues relate to their mission in a way that is more direct than organizations in other sectors. Finally, health systems often hold positions of trust in communities, a role that has become increasingly important as public trust in government erodes.10,11

Thus, while healthcare CEOs face unique pressures related to health-related social and political issues, little is known about their experiences responding to these issues. To fill this gap, we conducted a qualitative study with healthcare CEOs to explore their experiences engaging in health-related social and political issues, with a specific focus on systemic racism and abortion policy. The goal was to develop a richer understanding of CEO experiences, and identify areas for future study regarding the role and the impact of healthcare CEOs engaging in health-related social and political issues.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

In this qualitative study, we conducted semi-structured interviews with healthcare CEOs across the United States from February to July 2023. Participants were eligible if they were the CEO of a US-based hospital or health system. Using convenience and snowball sampling, a member of our research team (K.B.M.) recruited an initial sample of CEOs through email. Participants were consented verbally at the time of interview and no financial compensation was provided. The study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) reporting guidelines,12 and was deemed exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

A research team member trained in qualitative techniques (K.K.M, Z.B.) conducted audio-recorded semi-structured interviews via telephone or videoconferencing which lasted approximately 30 min. The interview guide (eAppendix 2 in Supplement 1) asked respondents about their role as CEO, factors they consider when navigating when and how to respond to social and political issues in their role as CEO, and whether they feel they have responded successfully.

The guide specifically probed how CEOs responded to the police killing of George Floyd in May 2020 and the US Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson decision in June 2022. When available, CEOs were asked to provide internal communications that had been sent to their employees surrounding these two specific incidents. These were reviewed for keywords and themes. The research team is described in eAppendix 3 in Supplement 1. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was reached.13

Data Coding and Analysis

Recordings were professionally transcribed and uploaded to QSR NVivo14 software for coding and analysis. We analyzed the data using thematic analysis, which involved familiarizing ourselves with the data, generating codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, and naming themes.14

The coding team coded transcripts systematically using an inductive and deductive approach, developing a structure that included codes that emerged from CEOs’ responses. An initial codebook was developed by three team members (K.K.M., J.S.G., Z.B.) and then revised iteratively throughout the coding process.

Coding was performed by two team members (K.K.M., J.S.G.). Approximately half (44%) of transcripts were coded independently by both coders. The degree of inter-rater agreement was measured using the \(\kappa\) coefficient. After independent coding, the coders identified coded segments with a \(\kappa\) < 0.6, and resolved discrepancies by discussion and consensus. The final \(\kappa\) coefficient average was 0.95, suggesting excellent inter-rater reliability. The research team then reviewed the coded data to identify and name themes.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the 25 CEOs. Almost half were between ages 60 and 69 (12 [48%]), 19 identified as male (76%), and 20 identified as White (80%). Many held advanced degrees and multiple degrees, including a Doctor of Medicine (9 [36%]), a Master’s in Health Administration (7 [28%]), or a Master’s in Business Administration (5 [20%]). Approximately half self-identified as Democrats (13 [55%]).

Table 2 shows the hospital and health system characteristics. Most were private non-profits (15 [60%]), 4 were affiliated with a public university (16%), and 2 were religiously affiliated (8%). There were 6 CEOs of single hospitals (24%) and 19 CEOs of health systems consisting of more than one hospital (76%) with a median of 10 hospitals in their system. Health systems from 44 states were included in our sample because several operated across state lines. We received copies of communications from 12 CEOs regarding the police killing of George Floyd and systemic racism and 6 CEOs regarding the Dobbs decision and changing abortion policies.

The interviews organized around four domains: (1) Perspectives on their Role, (2) Factors Impacting Engagement, (3) Improving Engagement, and (4) Experiences Responding to Recent Polarizing Events. Within these four domains, nine themes emerged.

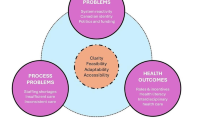

Within the first domain, two themes emerged: (1) Increasing pressure to engage and (2) Feelings Mixed on Role of Healthcare CEOs. Within the second domain, three themes emerged: (1) Personal Characteristics, (2) Organizational Characteristics, and (3) Political Environment. Within the third domain, two themes emerged: (1) Learning from Others is Key and (2) Measuring Success is Challenging. Within the fourth domain, CEOs reflected on their experiences responding to (1) Systemic Racism and (2) Changing Abortion Policies.

We summarize the nine major themes below and in Fig. 1. See eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1 for additional representative quotations.

Domain 1. Perspectives on Their Role

Theme 1. Increasing Pressure to Engage

Many CEOs described increasing pressure to respond to social and political issues in recent years. A frequently cited turning point was Trump’s candidacy: “Starting in 2015 with then candidate Trump’s candidacy… I needed to be more vocal about issues concerning race and racism, anti-immigrants, anti-Muslim – the Charlottesville incident clearly was extremely troubling.” Many felt that in recent years, employees had been more vocal about their beliefs, which some viewed positively and others viewed negatively. Multiple CEOs also discussed the “event fatigue” that occurs with trying to respond to issues: “If we speak out on every single issue, trying to represent [thousands of] unique perspectives, we really don’t then have a set of priorities or any unique position.”

Theme 2. Feelings Mixed on Role of Healthcare CEOs

CEOs had a range of views on their role in engaging in social and political issues and often described the difficult balance of commenting on public health-related issues with how politically polarizing it could be. Some felt they should not weigh in on controversial topics, such as abortion, while others said they shouldn’t take a “Republican” or “Democratic” position. Regardless of the issue, most respondents remarked about the difficulty navigating how to respond, especially as the country became more polarized.

Respondents also spoke about a responsibility to the community and commitment to the common good. Some framed this as a responsibility to provide patients with quality care, while others felt it was their role to lead on these issues and impact policy: “I do health care every day. This is what my life is. Politicians don’t spend every day in health care, right. I feel like we’re in a position where we can influence policy decisions. Because of our knowledge, we should try to do that.”

Domain 2. Factors Impacting Engagement

Theme 1. Personal Characteristics

Many CEOs discussed a desire to keep their personal beliefs out of their work. However, some felt that personal views heavily influenced their decision to be in healthcare leadership, so it became harder to separate them. Respondents discussed how their identity heavily influenced how they governed and made decisions as CEO, including their race, gender, upbringing, or training as a physician or nurse.

Multiple CEOs cited losing their job as a possible consequence of speaking up, but those who had been in their career for many years or felt more secure in their positions worried less about this. CEOs also identified personal attacks and employee alienation, among other negative impacts of speaking out. They cited receiving “hurtful” emails and being confronted by people in and outside the hospital.

Respondents also highlighted the positive impacts of speaking out, particularly around employee engagement and connection. Often, this came in the form of emails to the CEO or conversations with employees. When CEOs responded personally—with stories of their upbringing or life events—they received more supportive feedback from employees. One CEO said, “I do talk a lot about my own personal experiences and lessons learned and things that I’ve struggled with. And I think that makes us all a bit more relatable but also helps people appreciate we’re trying to get this right.”

Theme 2. Organizational Characteristics

For most CEOs, institutional characteristics impacted how they chose to respond more than their own personal characteristics. Those in larger systems spanning multiple states seemed to experience less direct pressure from employees to respond to specific incidents than those in hospitals concentrated in one state or city. CEOs of smaller rural hospitals discussed feeling pressure from the community because they were well-known figures. For religiously affiliated health systems, CEOs discussed the need to align with the procedures available at their hospitals, as most did not perform abortions regardless of state laws.

CEOs discussed the importance of understanding the organization and its different stakeholders: “You have multiple audiences. So, one audience is your board. One audience is the community. One audience is the faculty or physicians, because you got community docs, and you got noncommunity docs. And one audience is your staff. So, and then you have another problem if you’re [Health System Name] and you’re a state hospital.” Irrespective of their location, almost all CEOs agreed that having the board’s support was important when speaking out. Respondents were generally less concerned about the financial impact of speaking up. However, CEOs of health systems that received state funding discussed the importance of aligning what they said with the state legislature.

Theme 3. Political Environment

Many CEOs discussed how their role differed depending on their health system location. Those in more “Red states” or conservative areas tended to avoid topics like abortion. Those in predominately White, rural areas said there was less pressure to respond to the killing of George Floyd or the Dobbs decision, as employees were more concerned about COVID-19 vaccines and mask mandates. Those in “Blue states” expressed few worries about employee or political backlash when speaking to social and political topics: “It’s easier for me to speak on these issues if I’m on the bully pulpit in [‘Blue’ state] as opposed to somebody who might be running a health system in [‘Red’ state].”

Domain 3. Improving Engagement

Theme 1. Learning from Others Is Key

Many CEOs discussed the importance of having a team to help coordinate their responses. A handful said they relied on leaders outside their organization to help them navigate various issues. This was particularly important for CEOs of rural hospitals with a smaller internal leadership team. CEOs also discussed diversifying their team to better understand others’ perspectives. Most also pointed out the importance of recognizing mistakes in communication and being willing to listen and learn from their employees.

Theme 2. Measuring Success Is Challenging

When CEOs were asked how they measure success in communication, few described having any formal tracking process. They discussed connections with employees as a more reliable way to measure success, saying that positive and negative feedback was helpful because it meant that people were more actively responding to their statement. Some said town halls or other in-person events, as opposed to email, are often more helpful for understanding employee reactions.

Domain 4. Experiences Responding to Recent Polarizing Events

Theme 1. Responding to Systemic Racism

Most respondents discussed George Floyd’s death as a significant organizational turning point. In response, many hospitals formed diversity, equity, and inclusion committees; appointed diversity officers; began mandating employee bias training; or tried hiring more proactively from the community. Almost all CEOs wrote internal communications. Some CEOs wrote that this incident did not affect everyone equally, and it was clear that some employees, including Black or African American employees, were suffering more.

One CEO who wrote an “inclusive message” says he feels he “missed the mark” for not calling out the harms of systemic racism more explicitly. Most of those who wrote a communication used George Floyd’s name, but a few did not. One CEO shared that she received negative feedback for not using his name and felt this was a necessary learning experience.

A few CEOs wrote more personal stories about how it affected them, some because of their upbringing or identity, others because it had “a profound impact.” One CEO said, “I felt compelled to write a letter to the organization to both express my sort of personal reaction to sort of the culmination of a lot of our societal events that culminated into that, as well as to share perspectives as an African American man and an African American CEO. And I would tell you that that was the first time that I had ever sort of put more of my sort of personal self into communicating to the organization that I led.”

Some CEOs did not feel they needed to respond to this event. One said he did not respond because it did not occur in his state, and another thought it did not affect their institution where there were few non-White employees.

Theme 2. Responding to Changing Abortion Policies

There were a variety of responses from CEOs to the Dobbs decision. For CEOs of health systems in states where abortion remained legal, some felt it was essential to reiterate their commitment to providing abortion care. Others thought it was better to stay silent because it would not affect their care, and they would get involved in politics unnecessarily: “There’s nothing good about [CEO name] taking a position on the Dobbs decision when it’s not impacted any of us.” In states where abortion access would change, many CEOs responded to clarify the procedures providers could or could not offer. One CEO from a state where abortion is now illegal offered quiet support by not prohibiting faculty from making public statements.

Our review of internal communications revealed very few CEOs expressed disapproval of the decision. Those who chose to respond mostly reiterated the importance of decision-making remaining between the physician and their patient. Many of the same CEOs who chose not to say anything regarding Dobbs decided to respond to George Floyd’s killing. Some said Floyd’s killing felt more like a true injustice, and there was a greater moral obligation to respond than Dobbs, which felt like commenting on law. However, one CEO who was outspoken about her disappointment in Dobbs was surprised by how few CEOs spoke out publicly.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study examined healthcare CEOs’ experiences engaging in health-related social and political issues, specifically focusing on systemic racism and restrictive abortion policy. We found that CEOs experienced increasing pressure to engage in social and political issues and had mixed feelings regarding their role in responding to them. Personal, organizational, and political factors influenced their decisions about whether and how to respond. Given that CEOs are increasingly expected to respond to social and political polarizing issues which are known to affect employee engagement,1,2,3 these results have implications for how healthcare leaders address significant social policy issues that intersect with health which could have profound effects on their communities.

CEOs’ opinions differed regarding their role in engaging in polarizing social and political issues. Some thought it was important to be leaders in this space with the potential to influence policy. Others thought CEOs should remain apolitical and would be more effective leaders if they focused solely on patient care. This is consistent with a prior article that suggested healthcare CEOs are divided about whether they should speak out in polarizing times.15 Almost uniformly, CEOs agreed it was important to approach all problems from a public health perspective and avoid alienating employees. Interestingly, few CEOs were concerned that their public statements could alienate patients.

A complex balance of personal, organizational, and political factors influenced CEOs’ decisions around if and how to respond to issues. In general, CEOs appeared to more heavily weight organizational factors, although they increasingly shared personal anecdotes to connect with employees. Many CEOs highlighted the positive impacts of speaking out, including perceived employee engagement. Prior work in the corporate environment suggests that employee commitment to their organization is often contingent upon how their beliefs align with leadership in their organization, including the CEO, but it is unknown whether this also applies to the healthcare sector.3 More work is needed to examine how healthcare CEOs’ engagement with social and political issues affects employee dedication, turnover, and burnout, as well as patient satisfaction and trust in the organization. In addition, more work is needed to explore the fundamental question of whether leaders of hospitals or health systems are required to speak out on polarizing public issues. This point is particularly salient given recent resignations of leaders in other sectors (including universities) regarding their engagement on issues related to antisemitism and hate speech.16

Many CEOs expressed a sense of “event fatigue” about engaging in social and political issues, worrying that if they were to acknowledge every event, their response would lose importance. This concern is consistent with prior work in the corporate environment, which has suggested that it can be helpful to classify crises based on their “threat level” to determine if and how quickly a company should respond.17 Importantly, while the interviewed CEOs described increased communication around these issues, we did not measure related investment or impact. More work is needed to examine the presence or absence of concrete actions taken by healthcare CEOs to address health-related social issues — like systematic racism — in their institutions and communities.

Politically, CEOs in “Blue states” perceived it easier to discuss social and political topics because they worried less about employee or political backlash. In contrast, CEOs in “Red states” avoided issues like abortion, often because they were constrained by new laws that banned access. Importantly, while several CEOs viewed abortion access as health-related, many felt it was too political to engage in. These findings suggest that political polarization may prevent CEOs from engaging in topics they believe to be health-related and reflects factors that can affect their decision to engage in polarizing social and political issues. More work is needed to examine the degree to which the local political environment may be associated with CEO engagement and what impact, if any, a CEO’s degree of engagement impacts their job security, the organization’s financial health, employee satisfaction, quality of care, and health outcomes.

CEOs described strategies they used to improve their engagement, and many highlighted mistakes they had made and learned from, often around the terminology they used. CEOs had few strategies to measure the “success” of their engagement, suggesting more work is needed to develop metrics and examine the impact of CEOs’ investment and engagement around health-related social and political issues.

Limitations

A strength of this study is that it explored the experiences of healthcare CEOs, discovering perspectives that may not be elicited through survey-based research. However, this study also has limitations. First, we could not determine whether engagement of healthcare CEOs on health-related social and political issues was associated with objective improvements in care or employee satisfaction; future work should aim to link qualitative and quantitative analyses to understand these associations. We also could not determine statistical associations between personal, political, and organizational characteristics and the degree to which CEOs engaged. This association also deserves more study. Second, it is possible that interviewees’ responses were subject to social desirability bias. This concern may have been mitigated by assuring CEOs that their responses would be anonymized and aggregated. Third, the sample was also subject to nonresponse bias, meaning participating CEOs may be more interested in engaging in social and political issues. Fourth, as the CEOs in the initial sample were recruited through a co-author (and CEO), the sample is subject to selection bias. Additional CEOs were recruited through snowball sampling. To mitigate this bias, effort was made to contact CEOs from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, from for-profit and non-profit institutions, and states across the political spectrum. The final sample mainly comprised male CEOs who identified as non-Hispanic White; however given that as of 2019, 89% of all hospital CEOs were White, our sample is more racially diverse than national estimates.18 These results underscore the need to diversify senior hospital leadership. The majority of our sample also consisted of non-profit health systems; however, these comprise the majority of US hospitals.19 Approximately half (57%) of institutions were located in “Blue” states with the remainder in “Red” and “Purple” states. Finally, our study team resides in a “Purple” state; although we discussed reflexivity during study design and analysis, it is possible that this characteristic introduced bias into our study. Finally, although this study included CEOs from a range of hospitals and health systems, the results should be seen as hypothesis-generating and the perspectives of included CEOs may not generalize to other organizations.

CONCLUSIONS

In this qualitative study, we found that healthcare CEOs had diverse perspectives engaging in polarizing issues that largely depended on their personal beliefs, organizational characteristics, and the political environment. Our study helps to deepen our understanding of the experiences of healthcare CEOs in engaging in social and political issues and the factors that affect their decisions. Given that CEOs are increasingly expected to exercise their voice in response to major policy debates that have a direct impact on health and well-being, healthcare leaders play a uniquely vital role in influencing conversations around these consequential issues.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during this research are not publicly available due to the confidential nature of the data and the concern for anonymity of the participants but may be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Chatterji AK, Toffel MW. Assessing the Impact of CEO Activism. Organ Environ. 2019;32(2):159-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026619848144.

Mayer D. The Law and Ethics of CEO Social Activism. Journal of Law, Business, and Ethics. 2017;23(21):23-43.

Wowak AJ, Busenbark JR, Hambrick DC. How Do Employees React When Their CEO Speaks Out? Intra- and Extra-Firm Implications of CEO Sociopolitical Activism. Adm Sci Q. 2022;67(2):553-593. https://doi.org/10.1177/00018392221078584.

Cook T. Opinion Tim Cook: Pro-discrimination “religious freedom” laws are dangerous. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/pro-discrimination-religious-freedom-laws-are-dangerous-to-america/2015/03/29/bdb4ce9e-d66d-11e4-ba28-f2a685dc7f89_story.html. Published 2015. Accessed 26 March 2024.

More Than 100 Major CEOs & Business Leaders Urge North Carolina To Repeal Anti-LGBT Law. Human Rights Campaign. https://www.hrc.org/press-releases/more-than-100-major-ceos-business-leaders-demand-north-carolina-repeal-radi. Published 2016. Accessed 26 March 2024.

Thomas L. Read Nike CEO John Donahoe’s note to employees on racism: We must ‘get our own house in order.’ CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/05/nike-ceo-note-to-workers-on-racism-must-get-our-own-house-in-order.html. Published 2020. Accessed March 26, 2024.

Lucas A. Chief executives of 145 companies urge Senate to pass gun control laws. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/12/chief-executives-of-145-companies-urge-senate-to-pass-gun-control-laws.html. Published 2019. Accessed 26 March 2024.

Blair E. After protests, Disney CEO speaks out against Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill. NPR. https://www.wlrn.org/2022-03-08/after-protests-disney-ceo-speaks-out-against-floridas-dont-say-gay-bill. Published 2022. Accessed 26 March 2024.

Dowell EKP. Census Bureau’s 2018 County Business Patterns Provides Data on Over 1,200 Industries. United States Census Bureau. 2020. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/10/health-care-still-largest-united-states-employer.html. Accessed 26 March 2024.

Jones J. Confidence in U.S. Institutions Down; Average at New Low. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/394283/confidence-institutions-down-average-new-low.aspx. Accessed 26 March 2024.

Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report.; 2023. https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2023-03/2023%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Global%20Report%20FINAL.pdf Accessed 26 March 2024.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893-1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8.

Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 2020;42(8):846–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030.

Perna G. CEOs are divided on speaking out in polarizing times. Health Evolution. https://www.healthevolution.com/insider/ceos-are-divided-on-speaking-out-in-polarizing-times/. Published 2020. Accessed 26 March 2024.

Hartocollis A, Saul S. College Presidents Under Fire After Dodging Questions About Antisemitism. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/06/us/harvard-mit-penn-presidents-antisemitism.html. Published 2023. Accessed 26 March 2024.

Burnett JJ. A Strategic Approach To Managing Crises. Public Relat Rev. 1998;24(4):475-488.

Increasing and Sustaining Racial Diversity in Healthcare Leadership Policy Position. American College of Healthcare Executives. Published online 2020. https://www.ache.org/about-ache/our-story/our-commitments/policy-statements/increasing-and-sustaining-racial-diversity-in-healthcare-management. Accessed 26 March 2024.

KFF. State Health Facts: Hospitals by Ownership Type. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/hospitals-by-ownership/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Published 2022. Accessed March 26, 2024.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the late Judy A. Shea, Ph.D., Leon Hess Professor of Medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, for her invaluable contributions in designing the interview guide and codebook.

Funding

This work was supported with internal funds from Penn Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Bouchelle reported grants from the Academic Pediatric Association (Region II Young Investigator Award), the University of Pennsylvania Center for Guaranteed Income Research, CHOP PolicyLab and Clinical Futures Pilot, and Oscar and Elsa Mayer Foundation outside of this submitted work. Mr. Mahoney is on the boards of Lancaster General Health, Penn Medicine Board and Executive Committee, Pennsylvania Hospital, Princeton Health, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center. No other disclosures were reported.

Disclaimer

The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

This work was presented at the National Clinician Scholars Program Annual Meeting in New Haven, CT on October 12, 2023.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Meltzer, K.K., Bouchelle, Z., Grewal, J.S. et al. Leading a Healthcare Organization During a Period of Social Change: A Qualitative Study of Chief Executive Officers. J GEN INTERN MED (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08790-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08790-y