Abstract

Background

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic physicians worked on the front lines, immersed in uncertainty. Research into perspectives of frontline physicians has lagged behind clinical innovation throughout the pandemic.

Objective

To inform ongoing and future efforts in the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted a qualitative exploration of physician perspectives of the effects of policies and procedures as well as lessons learned while caring for patients during the height of the first wave in the spring of 2020.

Design

A confidential survey was emailed to a convenience sample. Survey questions included demographic data, participant role in the pandemic, and geographic location. Eleven open-ended questions explored their perspectives and advice they would give going forward. Broad areas covered included COVID-19-specific education, discharge planning, unintended consequences for patient care, mental health conditions to anticipate, and personal/institutional factors influencing workforce well-being amid the crisis.

Participants

We received fifty-five surveys from May through July 2020. Demographic data demonstrated sampling of frontline physicians working in various epicenters in the USA, and diversity in gender, race/ethnicity, and clinical specialty.

Approach

Inductive thematic analysis.

Key Results

Four themes emerged through data analysis: (1) Leadership can make or break morale; (2) Leadership should engage frontline workers throughout decision-making processes; (3) Novelty of COVID-19 led to unintended consequences in care delivery; and (4) Mental health sequelae will be profound and pervasive.

Conclusions

Our participants demonstrated the benefit of engaging frontline physicians as important stakeholders in policy generation, evaluation, and revision; they highlighted challenges, successes, unintended consequences, and lessons learned from various epicenters in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. There is much to be learned from the early COVID-19 pandemic crisis; our participants’ insights elucidate opportunities to examine institutional performance, effect policy change, and improve crisis management in order to better prepare for this and future pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

“She sleeps in a room with four other adults.” My heart sank. The day prior, on my first day caring for patients with COVID-19, I discharged a woman home with instructions to isolate away from her family. She was in her forties, and had survived breast cancer. We were so happy she survived COVID-19 and to speak to her directly in Spanish. But in the end, I sent her home to infect her family.

The lead author (CMG) took care of the patient in the aforementioned clinical case with unintended negative consequences. It was similar to stories shared by other frontline colleagues during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Physicians working on the front lines often resorted to anecdotal evidence for a sense of direction. Understandably, most research initially sought to inform direct clinical care (e.g., ICU management, antiviral therapies).1,2,3 Minimal research qualitatively explored frontline physicians’ perspectives regarding novel policies and procedures in real time during the first wave of the pandemic in the USA.4 As the pandemic progressed, more qualitative investigations were conducted exploring physician perspectives on working in subsequent waves of the pandemic,5, 6 the impact of COVID-19 on primary care,7, 8 integration of palliative medicine into intensive care units,9 and telehealth.10,11,12,13,14,15,16

To inform future efforts in the COVID-19 pandemic and prepare for future crises, we must understand frontline physicians’ perspectives from the first wave of the pandemic, when the least was known about this crisis. Given their central role in the healthcare system’s response, further crisis management without exploration of the perspectives of frontline physicians risks missing opportunities for success as well as opportunities to anticipate and proactively address sequelae for both patients and clinicians. Therefore, to address this gap in knowledge, we report a qualitative exploration of physician perspectives of their experiences working on the frontlines as well as lessons learned in real time while caring for patients during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020.

METHODS

As described above, the unintended consequences presented in the clinical vignette, as well as the anecdotal reports of physicians’ reactions to the chaos of the pandemic, inspired our qualitative study. We desired to obtain their perspectives in as close to real time as possible; therefore, we conducted an online qualitative study eliciting frontline physicians’ perspectives to questions through free-text narrative responses. We created a list of questions that participants could answer online if they found the time. Questions were developed in an iterative fashion by a hospitalist (CMG), an ambulatory generalist, and a subspecialist who had been redeployed to attend on newly created COVID wards. We piloted the initial set of questions with members of the Society of General Internal Medicine’s (SGIM) Health Equity Commission; we revised them for clarity. The confidential survey was emailed to a convenience sample through institutional and SGIM listservs (with up to two reminders sent weeks apart); it explained the voluntary nature of the study with an embedded link that participants could forward as well.

Participants answered questions related to demographic data, including their role in the pandemic and geographic location. Eleven open-ended questions explored their perspectives and advice they would give going forward (Appendix). Broad areas covered included COVID-19-specific education, discharge planning, unintended consequences for patient care, mental health conditions to anticipate, and personal/institutional factors influencing workforce well-being amid the crisis. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Free-text responses were analyzed through inductive thematic analysis.17 Two authors independently read through responses and attached notes to units of text. Responses were reviewed; a codebook and coding dictionary were developed and applied to the responses. Using a constant comparative approach,18 two authors analyzed the coded responses and from low inference codes generated potential themes. Through continued discussion, the authors reached a consensus on themes, the relationship between themes, and selected exemplary quotes.19 The only exceptions to this process were the mental health diagnoses listed by physicians analyzed by simple frequency analysis.

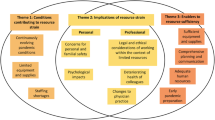

RESULTS

We received 55 completed surveys from May through July 2020. One international participant was excluded for a total N=54. Demographic data demonstrated sampling of frontline physicians working in various epicenters, mostly concentrated in New York (Table 1). Survey respondents represented 13 states, 41 (76%) were women, 30 (56%) identified as white, 50 (93%) worked as generalists in internal medicine, pediatrics, geriatrics, or family medicine, and 32 (59%) cared for patients on COVID-only floors (Table 1). Our analysis resulted in four themes related to leadership’s communication and decision-making practices, patient care, and mental health. The four themes include the following: (1) Leadership can make or break morale; (2) Leadership should engage frontline workers throughout decision-making processes; (3) Novelty of COVID-19 led to unintended consequences in care delivery; and (4) Mental health sequelae will be profound and pervasive. We report participants’ experiences and contextualize them with exemplary quotes below; suggestions made by participants are listed in Text Box 1. Participant quotes are designated by their participant number followed by E (epicenter) or NE (not epicenter) in order to illustrate the range of participant experiences. Epicenter refers to a point in a region with the highest disease activity.20

Text Box 1 Suggestions from participants in a qualitative survey study exploring lessons learned during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (May–July 2020).

Theme 2: Leadership should engage frontline workers throughout decision-making processes | |

• “[Going forward] share information between hospitals all around our country to develop proven best practices for the care of COVID patients” (P30). | |

• “The institution should limit the thank yous/hero worship and spend more time engaging front line workers in a debrief AND to be a part of future planning” (P18). | |

• “Your emergency plan should be fluid and may need implementation several times during the COVID crisis” (P06). | |

• “Training non-medical staff on appropriate PPE is of utmost importance” (P38). | |

Theme 3: Novelty of COVID-19 led to unintended consequences in care delivery | |

Compensating for changes in care delivery: | |

• “Have a plan for sedating newly intubated patients on the floor - this was a big issue as you had to wait for delivery of a controlled substance (e.g. versed, fentanyl) while the patient is agitated on vent” (P16). | |

• “[Create a] tracking system to ensure patients don’t get lost between the cracks when system-wide appointments are cancelled” (P10). | |

• “Schedule patients for telemedicine follow up within one week and every week until asymptomatic” (P11). | |

• “Patients ideally should be sent home with pulse oximeter - would be helpful to have these so that patients have objective measurement if dyspneic” (P16). | |

• “Accept that some of the patients are going to die- many more than we would otherwise accept. Push hard for goals of care conversations early in the hospital stay” (P37) | |

Combatting isolation: | |

• “We should have some type of buddy system for people who are isolated or alone” (P27). | |

• “set-up a way for patients to communicate with family members” (P53) | |

• “…a better system for family members to drop things off” (P37) | |

Improving the discharge process: | |

• “…collaborate with hotels and other sites for discharge before sending patients to their overcrowded apartments …set-up networks of subacute rehabilitation centers prepared to take our elderly and deconditioned patients with COVID-19 who we now know takes weeks or more to recover.” (P30) | |

• “Try to get patient refills of all meds from the hospital pharmacy so they don’t have to go out once they get home” (P31). | |

Theme 4: Mental health sequelae will be profound and pervasive | |

• To help with anticipated mental health needs we should “deploy widely in communities to identify now who needs help” (P30). | |

• “Line up long-term care of disaster related response” (P28) to support patients and communities. |

Theme 1: Leadership Can Make or Break Morale

Participants shared leadership practices whose efficacy varied widely. Effective leadership appeared to enhance morale for those on the receiving end of it. One participant enthused: “There was a ‘we’re all in this together’ feel, which honestly, made everything possible. My colleagues and I trusted our leadership…Have never been prouder to work for my organization than I am right now” (P55E). Trust in communication was a significant factor during the crisis. Effective communication from leadership enhanced trust. On the other hand, a lack of transparency stoked resentment and anger: “I pretty much lost all faith in my institution at one point. Don’t lie- if things are bad and you are struggling just say that and outline a plan to do better” (P16E). The crisis for frontline workers appeared compounded when issues of trust arose.

Consistent, unified communication was important. Within institutions, communication from leadership sometimes varied in quality between departments, further complicating clinical care: “My department gave good guidance and support but saw other departments struggling and it was challenging to focus on patient care with all the conflicts and lack of or miscommunication that was occurring” (P24E). Even when effective communication of guidelines was achieved, “running into systems that were not set up to follow those guidelines” (P16E) challenged effective delivery of care. Consistent, unified communication, if achieved, could still be thwarted by other factors, impeding the intended positive outcomes.

Leadership decisions beyond communication practices affected workforce morale. Favorable decisions included spreading the burden of caring for additional patients during the crisis across clinicians, not just those who would have been assigned on a given day to cover the hospital units: “Creating extra teams, extra ICUs, etc. Pulling non-medicine services to work on medicine floors” (P45E). Participants valued thoughtful staffing decisions. Conversely, decisions “putting very anxious clerical staff to work on the front lines without preparation” (P27NE) were deemed short-sighted. Additional positive decisions included “setting up check-ins with psychologists/psychiatrists/social workers for front line workers” (P19E) and “reducing number of patients per provider, checking temperatures at entry to hospital, and providing scrubs and PPE [personal protective equipment] at the entrance” (P43E). These and similar initiatives enhanced some participants’ morale.

Decisions negatively affecting morale angered those who felt unprotected by their organizations. Decisions and communication about PPE were commonly cited as detrimental to morale: “There should have been a policy of universal use of PPE with all patients regardless of suspicion of COVID-19 infection” (P25E). At times, PPE decisions were described as increasing unnecessary exposures to COVID-19 among healthcare workers: “Don’t allow people at the top [to] keep you from keeping yourself, your colleagues, your residents, and your patients safe” (P19E). When they did not feel protected by their institutions, participants reported advocating for themselves and others. Some participants noted that system-level barriers obstructed self-advocacy: “I purchased my own masks due to [the] PPE shortage, but in absence of fit testing made available to staff, was not able to use them in a safe manner” (P38E). Safety concerns during the crisis impacted morale.

Theme 2: Leadership Should Engage Frontline Workers Throughout Decision-making Processes

Participants described experiences with their leadership’s engagement of them as frontline stakeholders. Responses spanned a spectrum of engagement. For example, some participants felt disconnected from leadership, “It felt like the ground was shifting beneath you and you had no control. They treated providers like pawns...” (P07E). Fewer participants reported efforts to seek input, “[leadership] welcomed our feedback” (P55E). Leadership engagement impacted the reported perspectives and morale in general. For example, when leadership did not engage with frontline workers, well-meaning decisions were often viewed through a negative lens. One participant lamented, “Free food in the cafeteria is nice, but …I couldn’t even get a bottle of water when I was thirsty because water wasn’t allowed during ‘breakfast time’” (P37E).

Participants identified several shortcomings of new institutional policies. “Housing COVID + and COVID (test pending) or COVID (negative) In the same areas— didn’t make sense and continues to be baffling” (P29E). PPE came up again in this context: “Demanding compliance with PPE policies with sometimes threat of disciplinary actions lead to increased anxiety, distrust and exposures” (P38E). Physicians reported that some policies hindered their ability to deliver effective care. One participant noted “For a new illness [like COVID-19], restricting lab tests to specific specialty services is not helpful, especially for physicians who are directly taking care of patients” (P38E). Another participant reported, after pushing outpatient visits out into the future in anticipation of a surge that did not manifest, “Now in June, we are hitting rapidly increasing [COVID-19] numbers meanwhile trying to play ‘catch up’ for all the missed visits from months prior” (P10NE).

The lack of shared information between different health systems to help prepare frontline physicians frustrated some participants. One participant suggested “[reviewing] algorithms and practices from Italy and China to inform how we approach patients now” (P17E). Once the pandemic hit the USA, participants would have valued “knowledge about what was happening at other epicenters” (P47E). Given the knowledge that should have been available from other health systems, both within and outside the USA, the lack of information sharing felt like a missed opportunity to some participants.

Participants identified advice they would give to other frontline physicians and administrative leadership from their experiences at various epicenters: “Be an advocate for yourself and others…Don’t be afraid to speak up, your voice is needed” (P53E). Without frontline physician engagement, some participants felt constrained in their ability to plan and adjust workflows: “Be significantly more transparent about what is and isn't available within our healthcare system. We would gladly have one provider see 50 patients wearing one N95 if that is all of the N95s that we had for one day. Without knowing, we can't plan effectively” (P37E). Engaging physicians on the frontlines as valued stakeholders in policy making had perceived benefit in various aspects of the crisis. One insight gave a broad view of the issue: “I think this pandemic is a test of institutional morals and values. To the extent that institutions and physician are aligned in these areas, providers and patients will be incredibly pleased with the care given and received” (P55E). Incorporation of physicians’ suggestions depended on their engagement as stakeholders by leadership; exemplary suggestions are listed in the Text Box.

Theme 3: Novelty of COVID-19 Led to Unintended Consequences in Care Delivery

Participants reported that the inability to prepare for the COVID pandemic negatively affected healthcare delivery in four key areas: routine medical care, continuity of care, goals of care conversations/family engagement, and discharge planning. One participant experienced a “complete pivot to telehealth, without a great plan for labs/other measures that allow us to manage chronic disease” (P54NE). Caring for patients was challenging when procedural changes were not comprehensively implemented. Participants emphasized relying on their strong foundation of “medicine training” to improvise and make decisions in the face of clinical uncertainty: “…don’t just follow protocols if they make no sense for your patient” (P19E). The impact of the pandemic highlighted opportunities for revision of previously existing protocols.

Continuity of care was impacted by the pandemic: “I saw a gap in the ED's continued reliance on follow up in the primary care setting although this follow up could only occur in the virtual space…” (P55E). Challenges to continuity of care manifested in hospital discharge planning: “Patients may not be able to get the supportive care they need due to COVID distancing restrictions (e.g., face-to-face specialty consults, adequate PT, speech/swallow)” (P08E). The unpredictable clinical course of COVID-19 required creative approaches to discharge planning (Text Box 1). Silos inherent to the healthcare system further constrained coordinated care delivery. To counteract these unintended consequences, participants provided several suggestions (Text Box 1).

Goals of care discussions with patients and families, palliative care, and family engagement in general reportedly became more complex during the pandemic. The high death toll left participants identifying opportunities to have been better prepared, especially in palliative care. One palliative care physician expressed their frustration at the high number of resuscitation codes: “…Increased risk to healthcare workers providing many futile episodes of CPR. Approximately 30 codes per 24-hour period at the peak” (P25E). Better guidance in early goals of care discussions may have prevented some of the exposure to clinicians in settings where it was not possible to help some patients despite all efforts. Participants wanted assistance communicating with families when loved ones passed away: “Preparing for death and many patients decompensating…preparing to tell so many families that their family member is going to die” (P31E). This was especially pertinent when a no-visitor policy was in place: “Stopping visitation made caring for patients and aligning goals of care more difficult.” (P34E). Such challenges were often worse prior to widespread availability of video conferencing with families.

Participants identified strategies to adapt to new care delivery models, combat isolation for their patients, and improve the discharge process; exemplary suggestions are listed in Text Box 1.

Theme 4: Mental Health Sequelae Will Be Profound and Pervasive

Participants anticipated a sharp increase in patient and physician mental health needs. For patients, participants were concerned about substance misuse, survivor guilt, grief, and loneliness. The most frequently cited diagnoses included anxiety (30), depression (27), and PTSD (16). They also were concerned for “exacerbation of existing psychiatric disorders due to limited follow up with their doctors” (P38E). One participant noted that “Primary care follow-up will take a coordinated effort that can address PTSD and other mental health sequelae” (P15E). Participants predicted mental health sequelae for years to come and offered suggestions to proactively mitigate some of these sequelae, listed in Text Box 1.

For frontline physicians, participants anticipated a sharp increase in mental health conditions including formal diagnoses such as depression (N=24), anxiety (N=23), and PTSD (N=20), along with guilt and burnout. One participant stated, “Doing this for two months is wearing me down physically and mentally” (P40E); some anticipated they would “want to see a therapist” (P24E). Guilt plagued some participants for multiple reasons, including “overwhelming feeling of guilt when patients die” (P36E) and “calls for volunteers [to care for patients]” when they did not volunteer (P39E). Finally, the COVID-19 crisis stressed “already burned out” physicians: “This just makes it 10 times worse” (P40E). Contributors to burnout included “trauma of seeing mass death and morbidity, and functioning in a low-resourced and overburdened system” (P50E).

Participants reported effective ways to care for physicians, including virtual well-being meetings led by a clinical psychologist. Timing regarding mental health services was key: “During the peak crisis - no time for front-line providers to access it” (P25E). Participants wanted leadership to “acknowledge our fears” (P26E) and work on organizational workload issues to prevent mental health conditions: “set reasonable and sustainable precautions in place (people are burning out!)” (P10NE). Leadership should be cognizant of actions that might limit physicians seeking mental health services. One participant warned against “calling workers ‘hero’s’ and how that affects their ability to ask for help” (P48NE). Although mental health sequelae were expected “for years to come,” there was a sense of urgency to respond to the mental health sequelae experienced by physicians: “If just preparing now...it’s too late” (P30E).

Participants varied significantly in their skills and willingness to actively manage stress. Perspectives ranged from “daily yoga online” (P39E) to aversion about “anything containing the word ‘wellness.’ Please don't tell me to journal, eat healthfully, or take pro-biotics after I've watched people get intubated” (P41E). Strategies ranged from positive behaviors (e.g., “continue weekly therapy sessions” (P42E)) to negative coping behaviors (e.g., “daily alcohol” (P09E)). Health-promoting strategies included meditation, exercise, intentionality about nutrition, social support systems, and use of social media.

DISCUSSION

We sampled participants from various parts of the country, but with the greatest concentration in New York, the nation’s first epicenter when the least was known about the pandemic. Participants represented a range of ages (and subsequently, work experience) and medical specialties. Themes that emerged through analysis of this diverse group’s perspectives demonstrated the power of leadership to influence morale in a crisis, the need to be proactive to avoid or mitigate unintended consequences whenever possible, and the mental health sequelae some patient and physicians are likely to experience. As we strive toward a post-pandemic world, frontline physician perspectives, suggestions, and lessons learned can inform future crisis management in an effort to prevent “the cycle of panic then forget (that) has become routine.”21

Leadership during a crisis is especially challenging; it will affect teams and institutional culture for the foreseeable future.22 Participants described effective and ineffective leadership behaviors; these divergent experiences point out that low morale is not an inevitable consequence of a crisis. Others have reported significant increases in morale because of a sense that safety and physical and mental well-being is a priority in their department and institution.23 Effective communication is a factor within the control of institutional leaders, and can enhance trust,24 which is directly related to employee compliance.25 Open, honest, frequent communication has been shown to enhance morale,22, 25, 26 and is corroborated by our study in the context of a catastrophic pandemic. Effective communication is bi-directional22; clinical teams want to be engaged in decision-making.6, 24 Engagement of stakeholders during the COVID pandemic has contributed to bioethics policy for scarce resource allocation,27 and successful program initiatives for healthcare delivery and community engagement within this crisis.26 Intentional consideration of stakeholders from all specialties affected is important as well.28

While none of the hospitals entered into crisis standards of care during the early waves of the pandemic, physicians in our study reported several areas of care delivery that suffered, creating learning opportunities for healthcare systems. Participants were specifically keen to identify opportunities for specific training and learning from the experiences of others who were leaders in disease surveillance and healthcare innovation during the pandemic. Palliative care is an integral part of effective crisis management, with comprehensive guidelines published prior to the pandemic.29, 30 There is an inherent complexity of palliative care (and other) guidelines, given the potential for exacerbating disparities,30 further supporting the importance of engaging frontline physicians in ongoing decision-making. Our physicians noted concerns about the impact of the pandemic on the delivery of routine medical care and continuity of care. Promising initial evidence supports participants’ suggestions for intense post-discharge monitoring of patients with COVID-19,31 as well as creative methods of delivering care and accounting for the limitations of isolation recommendations,32 such as field hospitals, hotels, and dedicated quarantine facilities.33,34,35 One hotel providing isolation for homeless persons in Chicago collaborated with a community health center to provide daily medical care and wrap-around services; improvements in blood pressure and diabetes were noted, and pathways to permanent housing were identified.36 Our participants’ suggestions to combat loneliness and isolation may be particularly important given the higher prevalence and disproportionate impact among the elderly, who are at higher risk of mortality from COVID. Kuwahara et al. suggest change at the level of the preparedness phase (of disaster/emergency/crisis management), including “multiple plans and measures to maintain social ties should be prepared at the individual level (e.g., family, friends, neighborhood), organizational or community levels, and societal levels to prevent or mitigate the negative impact of social isolation and its related problems.37” Finally, shortages of PPE were a prominent issue early in the pandemic5, 28, 38; adequate PPE is an essential component to healthcare worker wellness in this crisis.39, 40 PPE has no longer become a critical issue for the majority of US hospitals, but the variation in hospital leadership’s ability to address the health and safety of frontline workers affected morale and had downstream effects. Such shortages could be avoided in future crises with timely, proactive measures stemming from the lessons learned in this pandemic.

The massive death toll and the subsequent trauma of handling the volume of deceased bodies posed severe mental health threats.29 High-profile cases in the media of frontline physicians having death by suicide due to the grief, guilt, and stress of COVID mortality. Healthcare workers’ wellness needs to be proactively planned for as part of comprehensive crisis preparedness.22, 30 Witnessing death on such a massive scale led to palpable trepidation on the part of healthcare workers.23 Failure to implement existing crisis care standards, when indicated, caused unnecessary moral distress.5, 29, 30 Moral distress can affect everyone; it has been suggested that it be openly discussed given that it is a healthy, rather than a pathological, response.41 Moral distress can be mitigated by systemic factors despite similar clinical exposures42; this highlights the power of systemic decisions to minimize moral distress in addition to addressing it through individual physician wellness. Physician wellness has been threatened in this pandemic; there are demonstrated associations between COVID quarantine and PTSD, psychological stress, substance use disorders, and consideration of resignation in healthcare workers.43 Stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in healthcare workers have been reported throughout the crisis.39 Programs to support healthcare workers’ mental health at an individual and institutional level and address increased burnout,44 may be critical to sustaining the presence and viability of the physician workforce.22, 29, 44 Additional suggestions include public awareness campaigns to encourage people to care for their mental health as well as their physical health during crises, as early in a crisis as possible.45

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we do not know how many potential participants were reached by our email invitation; therefore, we cannot calculate a response rate. However, we were not seeking to generalize experiences, but rather to qualitatively explore previously unknown physician perspectives. Our results, then, are meant to inform further investigations. Although we received responses from across the country, we did have a high proportion of responders from New York, likely reflecting both the local efforts to reach potential participants, as well as the fact that New York City was the nation’s first epicenter and frontline physicians were facing many unknowns. We may have missed opportunities for richer insights with our online free-text response survey as compared to focus groups; the ability to include perspectives of physicians on the frontlines who may have been unable to make the time to participate in a focus group mitigates that limitation given the objective of our study. Finally, our responses were limited to the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA, physician experiences and insights may have changed in subsequent waves.

CONCLUSION

It is unrealistic to think we will not have another pandemic within the span of our careers. Regardless, COVID-19 continues to reverberate across the globe as new variants arise. Our participants demonstrated the benefit of engaging frontline physicians as important stakeholders in institutional policy generation, evaluation, and revision; they highlighted challenges, successes, unintended consequences, and lessons learned in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. There is much to be learned from the early COVID-19 pandemic crisis; our participants’ insights elucidate opportunities to examine institutional performance, effect policy change, and improve crisis management in order to better prepare for this and future pandemics.

References

Nauka PC, Baron SW, Assa A, et al. Utility of D-dimer in predicting venous thromboembolism in non-mechanically ventilated COVID-19 survivors. Thromb Res. 2021;199:82-84.

Keller MJ, Kitsis EA, Arora S, et al. Effect of Systemic Glucocorticoids on Mortality or Mechanical Ventilation in Patients With COVID-19. J Hosp Med: an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2020;15(8):489-493.

Casadevall A, Pirofski LA, Joyner MJ. The Principles of Antibody Therapy for Infectious Diseases with Relevance for COVID-19. mBio. 2021;12(2):e03372-20.

Butler CR, Wong SPY, Wightman AG, O'Hare AM. US Clinicians’ Experiences and Perspectives on Resource Limitation and Patient Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2027315.

Blanchard J, Messman AM, Bentley SK, et al. In their own words: Experiences of emergency health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2022.

Rao H, Mancini D, Tong A, et al. Frontline interdisciplinary clinician perspectives on caring for patients with COVID-19: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e048712.

DePuccio MJ, Sullivan EE, Breton M, McKinstry D, Gaughan AA, McAlearney AS. The Impact of COVID-19 on Primary Care Teamwork: a Qualitative Study in Two States. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(8):2003-2008.

Sullivan EE, Breton M, McKinstry D, Phillips RS. COVID-19’s Perceived Impact on Primary Care in New England: A Qualitative Study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(2):265-273.

Schockett E, Ishola M, Wahrenbrock T, et al. The Impact of Integrating Palliative Medicine Into COVID-19 Critical Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62(1):153-158 e151.

Davoodi NM, Chen K, Zou M, et al. Emergency physician perspectives on using telehealth with older adults during COVID-19: A qualitative study. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(5):e12577.

Goldberg EM, Jimenez FN, Chen K, et al. Telehealth was beneficial during COVID-19 for older Americans: A qualitative study with physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(11):3034-3043.

DePuccio MJ, Gaughan AA, McAlearney AS. Making It Work: Physicians’ Perspectives on the Rapid Transition to Telemedicine. Telemed Rep. 2021;2(1):135-142.

Gomez T, Anaya YB, Shih KJ, Tarn DM. A Qualitative Study of Primary Care Physicians’ Experiences With Telemedicine During COVID-19. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(Suppl):S61-S70.

Goldberg EM, Lin MP, Burke LG, Jimenez FN, Davoodi NM, Merchant RC. Perspectives on Telehealth for older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic using the quadruple aim: interviews with 48 physicians. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):188.

McAlearney AS, Gaughan AA, Shiu-Yee K, DePuccio MJ. Silver Linings Around the Increased Use of Telehealth After the Emergence of COVID-19: Perspectives From Primary Care Physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13:21501319221099485.

DePuccio MJ, Gaughan AA, Shiu-Yee K, McAlearney AS. Doctoring from home: Physicians’ perspectives on the advantages of remote care delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2022;17(6):e0269264.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101.

Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):9-18.

Lingard L. Beyond the default colon: Effective use of quotes in qualitative research. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(6):360-364.

Bergquist S, Otten T, Sarich N. COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Policy Technol. 2020;9(4):623-638.

Godeau D, Petit A, Richard I, Roquelaure Y, Descatha A. Return-to-work, disabilities and occupational health in the age of COVID-19. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2021;47(5):408-409.

Walton M, Murray E, Christian MD. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020;9(3):241-247.

Edwards JA, Breitman I, Kovatch I, et al. Lessons Learned at a COVID-19 designated hospital. Am J Surg. 2021;221(1):62-64.

Lavoie B, Bourque CJ, Cote AJ, et al. The responsibility to care: lessons learned from emergency department workers’ perspectives during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. CJEM. 2022.

Everly GS, Wu AW, Cumpsty-Fowler CJ, Dang D, Potash JB. Leadership Principles to Decrease Psychological Casualties in COVID-19 and Other Disasters of Uncertainty. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1-3.

Doolittle BR, Richards B, Tarabar A, Ellman M, Tobin D. The day the residents left: lessons learnt from COVID-19 for ambulatory clinics. Fam Med Community Health. 2020;8(3). https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2020-000513.

Bruno B, Hurwitz HM, Mercer M, et al. Incorporating Stakeholder Perspectives on Scarce Resource Allocation: Lessons Learned from Policymaking in a Time of Crisis. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2021;30(2):390-402.

Sharma A, Maxwell CR, Farmer J, Greene-Chandos D, LaFaver K, Benameur K. Initial experiences of US neurologists in practice during the COVID-19 pandemic via survey. Neurology. 2020;95(5):215-220.

Institute of Medicine. Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response: Volume 1: Introduction and CSC Framework. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012.

Powell T, Chuang E. COVID in NYC: What We Could Do Better. Am J Bioeth. 2020;20(7):62-66.

Gordon WJ, Henderson D, DeSharone A, et al. Remote Patient Monitoring Program for Hospital Discharged COVID-19 Patients. Appl Clin Inform. 2020;11(5):792-801.

Madewell ZJ, Yang Y, Longini IM, Jr., Halloran ME, Dean NE. Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2031756.

Baughman AW, Hirschberg RE, Lucas LJ, et al. Pandemic Care Through Collaboration: Lessons From a COVID-19 Field Hospital. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(11):1563-1567.

Bruni T, Lalvani A, Richeldi L. Telemedicine-enabled Accelerated Discharge of Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 to Isolation in Repurposed Hotel Rooms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(4):508-510.

Choi H, Cho W, Kim MH, Hur JY. Public Health Emergency and Crisis Management: Case Study of SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3984.

Huggett TD, Tung EL, Cunningham M, et al. Assessment of a Hotel-Based Protective Housing Program for Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Management of Chronic Illness Among Persons Experiencing Homelessness. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2138464.

Kuwahara K, Kuroda A, Fukuda Y. COVID-19: Active measures to support community-dwelling older adults. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;36:101638.

Robblee J, Buse DC, Halker Singh RB, et al. Ten Eleven Things Not to Say to Healthcare Professionals During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Headache. 2020;60(8):1837-1845.

Shreffler J, Petrey J, Huecker M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Worker Wellness: A Scoping Review. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(5):1059-1066.

Harris G, Adalja A. ICU preparedness in pandemics: lessons learned from the coronavirus disease-2019 outbreak. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2021;27(2):73-78.

Khoo EJ, Lantos JD. Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(7):1323-1325.

Rosenwohl-Mack S, Dohan D, Matthews T, Batten JN, Dzeng E. Understanding Experiences of Moral Distress in End-of-Life Care Among US and UK Physician Trainees: a Comparative Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):1890-1897.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912-920.

Amanullah S, Ramesh Shankar R. The Impact of COVID-19 on Physician Burnout Globally: A Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(4):421.

Carbone SR. Flattening the curve of mental ill-health: the importance of primary prevention in managing the mental health impacts of COVID-19. Ment Health Prev. 2020;19:200185.

Contributors

The authors would like to thank Dr. Irene Blanco and Dr. Shani Scott for their assistance in developing the initial survey questions and Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith, Dr. Marshall Fleurant and members of SGIM Health Equity Commission for their guidance refining survey questions.

Funding

Dr. Gonzalez is funded by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities K23MD014178.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gonzalez, C.M., Hossain, O. & Peek, M.E. Frontline Physician Perspectives on Their Experiences Working During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 4233–4240 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07792-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07792-y