Abstract

Background

The United States is facing a primary care physician shortage. Internal medicine (IM) primary care residency programs have expanded substantially in the past several decades, but there is a paucity of literature on their characteristics and graduate outcomes.

Objective

We aimed to characterize the current US IM primary care residency landscape, assess graduate outcomes, and identify unique programmatic or curricular factors that may be associated with a high proportion of graduates pursuing primary care careers.

Design

Cross-sectional study

Participants

Seventy out of 100 (70%) IM primary care program directors completed the survey.

Main Measures

Descriptive analyses of program characteristics, educational curricula, clinical training experiences, and graduate outcomes were performed. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine the association between ≥ 50% of graduates in 2016 and 2017 entering a primary care career and program characteristics, educational curricula, and clinical training experiences.

Key Results

Over half of IM primary care program graduates in 2016 and 2017 pursued a primary care career upon residency graduation. The majority of program, curricular, and clinical training factors assessed were not associated with programs that have a majority of their graduates pursuing a primary care career path. However, programs with a majority of program graduates entering a primary care career were less likely to have X + Y scheduling compared to the other programs.

Conclusions

IM primary care residency programs are generally succeeding in their mission in that the majority of graduates are heading into primary care careers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Primary care has been associated with better health outcomes, higher patient satisfaction, and decreased health care cost.1,2,3,4 However, the United States is currently facing a primary care physician (PCP) shortage with recent estimates projecting a need for up to 43,000 additional physicians by 2030.5 General internists make up about one third of the national PCP workforce,6 but the numbers of internists pursuing primary care careers have been declining over the past several decades.7 Although increasing numbers of advanced practice providers, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants, may help alleviate some primary care demand, current workforce projections demonstrate that there will still be a significant primary care practitioner shortage.8, 9 Primary care physicians may play an especially important role in managing an aging population with multiple complex conditions.10, 11 In the early 1970s, internal medicine (IM) primary care residency programs and tracks were developed to help produce more primary care internists.12 Recent evidence suggests that graduates of IM primary care programs are twice as likely to pursue primary care careers than their categorical IM resident colleagues.7

The United States has seen a significant increase in the number of IM primary care programs over the past few decades.13 There is a paucity of literature describing the characteristics and curricula of IM primary care residency programs. The objectives of this study were to characterize the IM primary care residency landscape in this country, determine graduate outcomes, and assess whether unique programmatic or curricular factors were associated with having graduates pursue primary care careers.

METHODS

Subjects, Setting, and Study Design

We conducted a survey of US internal medicine primary care program directors (PDs) in 2017. Internal medicine primary care PDs were identified as part of a prior study about the locations of IM primary care programs.13 This list was augmented with input from two primary care program director interest groups at the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine and the Society of General Internal Medicine.

We designed and iteratively revised the survey based on feedback from pilot testing with primary care IM PDs. Survey questions, including areas to be explored, were formulated based on a review of the published literature, discussions with several current primary care PDs, presentations at medical education academic conferences, and input from internists practicing in primary care who graduated from primary care IM programs.

Survey Instrument and Data Collection

We designed the survey around four sections. First, we asked about general primary care training program characteristics such as if their program possesses a distinct National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) internal medicine primary care program code and number of positions available (and filled) for the 2017–2018 academic year. The second part of the survey addressed primary care program educational curricula and learning environment. Third, the instrument collected information about primary care clinical training experiences including the total number of clinic sessions per resident at the primary continuity clinic site and the presence of a second ambulatory continuity clinic site for residents. Finally, the survey captured data about the jobs or training programs that recent graduates pursued after residency: “For your [2016 or 2017] cohort of graduates, please list the number of primary care track graduates that took the following jobs or went on to further training below.” Respondents were asked to enter the number of graduates next to a list of 14 answer choices.

All PDs were sent an email link to the online survey administered through Qualtrics. Potential respondents received up to two follow-up reminder emails. We assigned each program to its respective geographic region as denoted by the U.S. Census Bureau.14 This study was exempted by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive characteristics, including means and standard deviations, for the applicable variables were computed. The number of total half-day clinic sessions at the primary clinic was dichotomized at 160, which was the median number of reported half-day clinic sessions. We stratified results by programs with a unique NRMP primary care program code (NRMP program) versus programs that do not possess a NRMP primary care code (non-NRMP programs) because the NRMP programs with a primary care code are easily identified by medical students interested in pursuing primary care internal medicine and therefore may have differences in graduate outcomes compared to non-NRMP programs. We used bivariate logistic regression analysis to evaluate the association between having a majority of graduates (≥ 50%) pursue a primary care career and other measured variables (program characteristics, educational curricula/learning environment, and clinical training experiences). Primary care career was defined to include pursuing outpatient private practice general internal medicine, academic general internal medicine, outpatient clinic care for the underserved, addiction medicine fellowship, or geriatrics fellowship. Since chief residency is a temporary position and we did not have data on their subsequent career plans, chief residents were excluded from the calculation of primary care career outcomes. We used multivariate logistic regression analysis to evaluate the association between having a majority of program graduates pursue a primary care career and the independent variables of the presence of a X + Y scheduling model and a geographic region of the program. We conducted a sensitivity analysis by including graduates who pursued a general internal medicine (GIM) fellowship. Analyses were conducted using Stata 15.0.

RESULTS

Of the 100 identified primary care program directors, 70 (70%) completed the survey. The majority of respondents (n = 46, 66%) were affiliated with programs having a distinct NRMP internal medicine primary care program code (NRMP programs). Primary care program directors from NRMP programs were significantly more likely to have been in their current positions for ≥ 5 years compared to non-NRMP primary care program directors (66.7% vs. 21.7%, p < 0.001).

Program Characteristics

The majority of NRMP programs were established before 2000 while non-NRMP programs tended to have been established in 2000 or later (Table 1). Primary care programs were mostly located in the northeast (44.3%), south (21.4%), and west (21.4%). NRMP programs had an average fill rate of available spots of 91.0% versus 74.4% for non-NRMP programs (p = 0.06). Over half of the programs reported using a X + Y scheduling model. Only a quarter of programs have recurrent home visits as part of the training experience.

Clinical Practice Characteristics

Most programs had their primary resident continuity clinic site at a clinic based at a hospital or academic center (90.2%), and most clinic sites were patient-centered medical homes. Residents saw on average six patients in a half-day clinic session at their primary continuity clinic, which had an average no show rate of 20.7%. NRMP programs were more likely to have over 100 patients on their graduating residents’ patient panels compared to non-NRMP programs (p = 0.03). Half of the programs had second continuity clinics, and residents generally had fewer than a total of 50 half-day sessions at these second sites over the course of residency.

Program Graduates

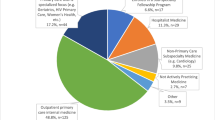

Fifty-seven percent of IM primary care program graduates from June 2016 and 2017 pursued a primary care career (including addiction medicine fellowship and geriatrics fellowship) at the end of residency training (Table 1). Sixty-one percent of NRMP program graduates entered a primary care career compared to 44% of non-NRMP graduates (p ≤ 0.001). Figure 1 displays the percentage of primary care programs (NRMP vs. non-NRMP programs) and their associated rates of graduates pursuing primary care careers during the years of 2016 and 2017. Sixty-nine percent of the NRMP programs (n = 29) graduated > 50% of their residents to primary care career paths as compared to 60% of non-NRMP programs (n = 12). Table 2 describes the immediate plans of primary care program graduates in 2016 and 2017. The most common post-graduation pursuits for those not engaging in a primary care career after residency were hospital medicine (14.4%) and other medicine subspecialty fellowships (15.6%).

Factors Associated with Most Graduates Pursuing Primary Care Career

Table 3 displays the results of the bivariate logistic regression analysis examining factors associated with ≥ 50% of graduates entering a primary care career. The only factor significantly associated with a majority of program graduates entering primary care careers was the use of X + Y scheduling model by the training program. Programs having a majority of program graduates entering primary care careers were less likely to have X + Y scheduling compared to the other programs (OR = 0.2, 95% CI = 0.1 to 0.9, p = 0.04). After adjusting for the geographic region, programs that used the X + Y scheduling model remained significantly less likely to have a majority of their graduates enter a primary care career (OR = 0.2, 95% CI = 0.1 to 0.9, p = 0.04). However, 97% of PDs that used the X + Y scheduling model (n = 33) believed that this model has enhanced the trainee experience with ambulatory medicine (as compared with their prior scheduling model). In a sensitivity analysis including GIM fellowship, X + Y scheduling was no longer significantly associated with the outcome (OR = 0.3, 95% CI = 0.0 to 1.4, p = 0.11).

DISCUSSION

In this national study, we found that 57% of graduates of US internal medicine primary care programs pursue primary care careers after graduation. NRMP primary care programs were more successful in having more of their graduates pursue careers in primary care directly after graduation compared to non-NRMP programs. Similarly, NRMP programs also trended toward a higher fill rate of available primary care program positions compared to non-NRMP programs. While the majority of programmatic and curricular factors assessed through our survey were not associated with having the majority of a program’s graduates pursuing primary care careers upon graduation, X + Y scheduling was inversely associated with this outcome.

To our knowledge, this is the only national collective assessment of program characteristics, curricula, and graduate outcomes of internal medicine primary care residency programs. There have been prior studies evaluating graduate outcomes from individual primary care programs.12, 15,16,17 In single-program retrospective studies that evaluated primary care graduate outcomes prior to 2006 (majority of the studies examined outcomes before 1994), most reported rates of graduates pursuing primary care careers were in the 70–90% range.12, 15,16,17 In an old national cohort study of internal medicine residents that trained between 1977 and 1982, 72% of IM primary care residency graduates chose primary care careers compared to 54% of categorical residency graduates.18 This finding is in contrast to a recent 2012 study of IM residents that demonstrated that less than 20% of categorical IM residents and less than 40% of primary care residents plan to pursue primary care careers after graduation.7 In addition, recent single-institution studies published in the past decade have demonstrated that the rate of graduates pursuing primary care was between 51 and 59%.19,20,21 These recent study results are more consistent with the findings of our national assessment of US internal medicine primary care programs. From our study, we learned that NRMP programs tended to have a higher fill rate of available positions with a higher proportion of graduates pursuing primary care careers. Because getting an NRMP primary care code is straightforward, we imagine that these data may encourage some primary care programs/tracks to apply for this designation. This observational study cannot explain the observed differences, but perhaps these NRMP-branded programs are better able to attract medical students who are most committed to a primary care career (because they are easily identified as a separate program from the categorical track) or the NRMP-specific label may permeate the culture in a way that validates the primary care career choice.

Prior research has demonstrated associations between residents’ satisfaction with their primary continuity clinic (e.g., satisfaction with the number of patients seen in clinic, continuity with clinic patients) and primary care career choice.22 A recent qualitative study examining such factors discovered that more patients seen‚ a diversity of outpatient experiences, and supportive resources that address social determinants of health all positively influence the pursuit of primary care careers among trainees.23 Not surprisingly, scheduling models that limit inpatient and outpatient conflict for residents may translate into greater resident satisfaction with their training.24 X + Y scheduling, a model that schedules residents’ inpatient or non-ambulatory rotations (“X” blocks) in discrete periods with alternating ambulatory or “Y” blocks, is instituted specifically to decrease the conflict between inpatient and outpatient patient care responsibilities.25, 26 Several studies of X + Y scheduling have found this model to be associated with less care fragmentation, increased perception of clinic continuity among residents, and higher resident satisfaction.27,28,29 Our study unearthed the association that primary care programs using the X + Y scheduling model were less likely to have a majority of their program graduates pursue primary care at the time of graduation. Of course, not all X + Y models are the same (e.g., distribution of inpatient vs. outpatient time, time allotted to each setting before switching), and these nuances may influence the link between X + Y scheduling and graduate career choice. Further study with attention to specific details may be required in order to better understand these associations.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, it is possible that non-responders may have different perspectives. While non-response bias is always possible, the high response rate and the comparable proportions of non-responders from NRMP and non-NRMP programs make this less likely. Second, there is potential of inaccurate recall regarding graduate outcomes. However, we asked program directors to recall information from their most recent two cohorts of graduates. Given that most programs are small, typically with less than ten residents per year, we expect recall bias to be minimal. Third, our study only assessed career decisions immediately after graduation and did not account for future changes. Finally, several factors that are known to be positively associated with primary care career choice, such as primary care mentorship and a supportive learning environment, would have been problematic to ascertain from our survey of program directors and so these elements were not captured. Further studies assessing these variables among current and former primary care residents are needed.

Our study demonstrates that the majority of US internal medicine primary care program graduates pursue a primary care career upon graduation. In the context of a generalist physician shortage and because fewer than one fifth of categorical IM residents pursue careers in primary care,7 internal medicine primary care programs are an important conduit to increase the number of general internists. In our future work, we plan to study primary care program graduates directly; such research will help to determine the optimal training and environment for augmenting the generalist workforce with clinically excellent physicians.

References

Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2007;37(1):111–126. https://doi.org/10.2190/3431-G6T7-37M8-P224.

Chang C, Stukel TA, Flood AB, Goodman DC. Primary care physician workforce. JAMA. 2015;305(20):2096–2105.

Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Aff. 2004;23(SUPPL). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.W4.184.

Kravet SJ, Shore AD, Miller R, Green GB, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Health care utilization and the proportion of primary care physicians. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):142–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.021.

Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, Lacobucci W. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2015 to 2030 (2017 Update). 2016:1–51.

Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6):503–510. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1431.INTRODUCTION.

West CP, Dupras DM. General medicine vs subspecialty career plans among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2241–2247. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.47535.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services HR and SA. Projecting the Supply and Demand for Primary Care Practitioners Through 2020. Rockville, Maryland; 2013. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/projectingprimarycare.pdf.

Martsolf GR, Barnes H, Richards MR, Ray KN, Brom HM, McHugh MD. Employment of advanced practice clinicians in physician practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):988–990. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1515.

Buerhaus P, Perloff J, Clarke S, O’Reilly-Jacob M, Zolotusky G, DesRoches CM. Quality of primary care provided to medicare beneficiaries by nurse practitioners and physicians. Med Care. 2018;56(6):484–490. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000908.

Ward BW, Schiller JS, Goodman RA. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: a 2012 update. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E62. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd11.130389.

McPhee SJ, Mitchell TF, Schroeder SA, Perez-Stable EJ, Bindman AB. Training in a primary care internal medicine residency program. The first ten years . JAMA. 1987;258(11):1491–1495.

O’Rourke P, Tseng E, Levine R, Shalaby M, Wright S. The current State of US internal medicine primary care training. Am J Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.05.006.

United States Census Bureau. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2018.

Perez JC, Brickner PW, Ramis CM. Preparing physicians for careers in primary care internal medicine: 17 years of residency experience. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1997;74(1):20–30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9210999%0A http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC2359253.

Strelnick AH, Bateman WB, Jones C, et al. Graduate primary care training: a collaborative alternative for family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109(4):324–334.

Witzburg RA, Noble J. Career development among residents completing primary care and traditional residencies in medicine at the Boston City Hospital, 1974-1983. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(1):48–53.

Noble J, Friedman RH, Starfield B, Ash A, Black C. Career differences between primary care and traditional trainees in internal medicine and pediatrics. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(6):482–487. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-116-6-482.

Stanley M, O’Brien B, Julian K, et al. Is training in a primary care internal medicine residency associated with a career in primary care medicine? J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1333–1338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3356-9.

Chen D, Reinert S, Landau C, McGarry K. An evaluation of career paths among 30 years of general internal medicine/primary care internal medicine residency graduates. R I Med J (2013). 2014;97(10):50–54.

Dick JF 3rd, Wilper AP, Smith S, Wipf J. The effect of rural training experiences during residency on the selection of primary care careers: a retrospective cohort study from a single large internal medicine residency program. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23(1):53–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2011.536893.

Peccoralo LA, Tackett S, Ward L, et al. Resident satisfaction with continuity clinic and career choice in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1020–1027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2280-5.

Long T, Chaiyachati K, Bosu O, et al. Why aren’t more primary care residents going into primary care? A qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(12):1452–1459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3825-9.

Stepczynski J, Holt SR, Ellman MS, Tobin D, Doolittle BR. Factors affecting resident satisfaction in continuity clinic—a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4469-8.

Noronha C, Chaudhry S, Chacko K, et al. X + Y scheduling models in internal medicine residency programs: a national survey of program directors’ perspectives. Am J Med. 2018;131(1):107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.09.012.

Shalaby M, Yaich S, Donnelly J, Chippendale R, DeOliveira MC, Noronha C. X + Y scheduling models for internal medicine residency programs—a look back and a look forward. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):639–642. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00034.1.

Heist K, Guese M, Nikels M, Swigris R, Chacko K. Impact of 4+1 block scheduling on patient care continuity in resident clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(8):1195–1199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2750-4.

Chaudhry SI, Balwan S, Friedman KA, et al. Moving forward in GME reform: A 4 + 1 model of resident ambulatory training. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1100–1104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2387-3.

Mariotti JL, Shalaby M, Fitzgibbons JP. The 4∶1 schedule: a novel template for internal medicine residencies. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(4):541–547. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-10-00044.1.

Funding

Dr. Wright is the Anne Gaines and G. Thomas Miller Professor of Medicine which is supported through the Johns Hopkins Center for Innovative Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Prior Presentations

This work was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in April 2018.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Rourke, P., Tseng, E., Chacko, K. et al. A National Survey of Internal Medicine Primary Care Residency Program Directors. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 1207–1212 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04984-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04984-x