Abstract

Background

Although primary care is associated with population health benefits, the supply of primary care physicians continues to decline. Internal medicine (IM) primary care residency programs have produced graduates that pursue primary care; however, it is uncertain what characteristics and training factors most affect primary care career choice.

Objective

To assess factors that influenced IM primary care residents to pursue a career in primary care versus a non-primary care career.

Design

Multi-institutional cross-sectional study.

Participants

IM primary care residency graduates from seven residency programs from 2014 to 2019.

Main Measures

Descriptive analyses of respondent characteristics, residency training experiences, and graduate outcomes were performed. Bivariate logistic regression analyses were used to assess associations between primary care career choice with both graduate characteristics and training experiences.

Key Results

There were 256/314 (82%) residents completing the survey. Sixty-six percent of respondents (n = 169) practiced primary care or primary care with a specialized focus such as geriatrics, HIV primary care, or women’s health. Respondents who pursued a primary care career were more likely to report the following as positive influences on their career choice: resident continuity clinic experience, nature of the PCP-patient relationship, ability to care for a broad spectrum of patient pathology, breadth of knowledge and skills, relationship with primary care mentors during residency training, relationship with fellow primary care residents during training, and lifestyle/work hours (all p < 0.05). Respondents who did not pursue a primary care career were more likely to agree that the following factors detracted them from a primary care career: excessive administrative burden, demanding clinical work, and concern about burnout in a primary care career (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Efforts to optimize the outpatient continuity clinic experience for residents, cultivate a supportive learning community of primary care mentors and residents, and decrease administrative burden in primary care may promote primary care career choice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Primary care is foundational to optimizing population health.1 Primary care has been associated with numerous benefits to patients and the health system, including enhanced patient satisfaction, less emergency department visits, fewer hospital admissions, reduced mortality, and lower costs.2,3,4,5,6,7,8 However, the Association of American Medical Colleges has projected a shortfall of between 21,400 and 55,400 primary care physicians (PCP) by 2033.9 Access to this valuable resource, which is already limited, will be further restricted.9

General internists make up approximately one-third of the United States’ PCP workforce.10 Unfortunately, interest among internal medicine (IM) residents in primary care careers continues to decline.11,12,13 Over the past decade, the percentage of IM resident physicians planning to pursue a general internal medicine career has decreased by nearly half.13 Per 2019 to 2021 IM in-training exam data, fewer than 10% of residents planned to pursue a career in general internal medicine compared to 15% that intended to go into hospital medicine and 68% that anticipated working in a medical subspecialty.13

IM primary care residency tracks or programs have seen that a majority of their graduates wind up practicing primary care or in primary care related fields such as geriatrics or addiction medicine.14,15 While the number of IM primary care programs have increased and grown in popularity,16 it is poorly understood which components of these programs most impactfully influence residents’ ultimate decision to pursue careers in primary care. Such information could help programs to optimize their training to inspire more residents into the workforce. Therefore, we conducted a survey of primary care residency graduates to elucidate the factors that influenced their resolve to pursue a primary care versus a non-primary care career.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a cross-sectional electronic survey that included all IM primary care residency graduates who completed their training between 2014 and 2019 from seven institutions: Ascension St. Vincent, Emory University, Johns Hopkins Bayview, University of Colorado, University of Pennsylvania, University of California Los Angeles, and the University of Washington. These academic and community-based residency programs were selected due to geographic diversity and varying program size.

Survey Instrument

We based survey items on studies that have evaluated factors influencing primary care education and workforce issues; we also integrated expert opinion from several primary care residency program directors and others.12,17,18 The survey was piloted with two IM primary care residency graduates who graduated outside of the study period from one of the study institutions and revised based on their feedback.

At the start of the survey (Appendix), primary care was defined as “the level of our health services system that provides entry into the system for all new needs and problems, provides person-focused (not disease-oriented) care over time, provides care for all but very uncommon or unusual conditions, and coordinates or integrates care, regardless of where the care is delivered and who provides it.”19 The survey topics included graduates’ fellowship and employment history after residency training (including characteristics of and satisfaction with current work), interest in primary care as a career choice prior to residency and after residency, factors influencing primary care career choice (e.g., presence of primary care mentors, residency continuity clinic experience, income potential, and perception of administrative burden), and satisfaction with various components of their residency experience. We also asked respondents to self-report age, gender, racial or ethnic heritage, year of graduation from residency, and financial debt from medical school.

Survey Distribution

The survey was emailed via Qualtrics in fall 2020. Non-respondents received two additional reminder emails 2 weeks apart to encourage participation.

Statistical Analysis

After reviewing responses, we excluded current general internal medicine and geriatrics fellows (n = 6) from the study since it was unclear if they would be pursuing primary care careers after fellowship. We conducted descriptive analyses to summarize responses for all items. We performed chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate for categorical variables and t-tests for means when comparing demographic data. We performed bivariate logistic regressions using primary care practice vs not as the dependent variable and adjusted for clustering of variance by program. For questions using a Likert scale for satisfaction, we dichotomized answers (satisfied or very satisfied versus neutral or dissatisfied). For questions using a Likert scale for agreement, we dichotomized answers (agree or strongly agree versus disagree or strongly disagree). For questions using a Likert scale for interest, we dichotomized answers (fairly or fully committed versus disinterested or opposed). Analyses were conducted using Stata (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LP). This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Of 314 eligible primary care residency graduates, 256 responded to the survey (82%).

Graduate Characteristics

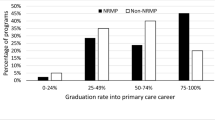

Almost two-thirds of respondents (n = 169, 66%) currently practice primary care or primary care with a specialized focus such as geriatrics, HIV primary care, or women’s health (Fig. 1). Characteristics of respondents are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in self-reported demographics among graduates who pursued a primary care career compared with those graduates that did not pursue primary care as a career (all p > 0.05). There was no significant difference in primary care career choice among respondents regardless of their years out from training (p = 0.767) or the specific residency program they attended (p = 0.429). While there was no significant difference in reported primary care career interest at the beginning of residency training among respondents who ultimately chose a primary care career versus respondents who did not (89% vs. 92%, p = 0.235), by the end of residency the group that went into primary care careers were much more interested in this path (95% vs. 42%, p < 0.001).

Perceptions of Factors Influencing Primary Care Career Choice

Table 2 displays the association between various factors on primary care career choice among IM primary care residency graduates.

Table 3 shows the association between graduate perspectives after completing internal medicine primary care residency and primary care career choice.

There was no significant difference in the reported influence of primary care clinical experiences or mentorship prior to their residency training related to respondents’ primary care career choice. There was also no significant difference between respondents’ career choice and their end-of-residency perceptions about income potential or prestige associated with a primary care career, or their opportunities for loan repayment associated with a primary care career.

However, respondents who pursued a primary care career were more likely to report the following as positive influences on career choice compared with those respondents who did not choose primary care: resident continuity clinic experience (p < 0.001), the nature of the PCP-patient relationship (p = 0.005), ability to care for a broad spectrum of patient pathology (p < 0.001), breadth of knowledge and skills (p < 0.001), relationship with primary care mentors during residency training (p = 0.015), relationship with fellow primary care residents during training (p = 0.017), and lifestyle/work hours (p < 0.001).

Graduates that pursued primary care careers were also more likely to have had higher satisfaction with interdisciplinary case management in their outpatient residency continuity clinic experience (p = 0.007). They were also more likely to find primary care clinical work extremely fulfilling (p < 0.001).

Respondents who did not pursue a primary care career were more likely to agree that the following factors undermined their interest in a primary care career: excessive administrative burden (86.2% vs. 73.4%, p = 0.002), clinical work being overwhelmingly demanding (83.9% vs. 75.1%, p = 0.005), and concern about higher burnout potential in primary care (82.8% vs. 57.4%, < 0.001).

Over half of all respondents (51%) reported that faculty members during residency made disparaging remarks about primary care and over one-fifth of respondents reported that some faculty discouraged them from pursuing primary care; there was no significant difference among respondents who pursued a primary care career versus those who did not.

Although over one-third of respondents ultimately did not choose a primary care career, the vast majority of all respondents, including 97.5% of respondents who did not pursue a primary care career, reported that completing the primary care track residency experience was valuable for them.

DISCUSSION

In this survey of six cohorts of IM primary care residency graduates from seven programs, we found that most graduates were practicing primary care. We also identified a variety of clinical and programmatic features that influenced primary care career choice among IM primary care residency graduates.

Similar to other published studies, our data support that satisfaction with the residency continuity clinic experience may be pivotal to primary care career choice.12,20,21,22 A 2018 systematic review found resident satisfaction with their continuity clinic experience was associated with minimized inpatient and outpatient conflict during training, patient-resident physician continuity in clinic, and exposure to a dedicated outpatient faculty.23 IM primary care residents can also be frustrated when unable to address patients’ unmet social needs in clinic; this points to the benefit to both patients and trainees of interdisciplinary case management support in resident clinics.24 Preference for and finding pleasure in the core aspects of the primary care physician role, particularly the nature and continuity of the PCP-patient relationship and breadth of clinical presentations, have also been associated with primary care career choice.17,22 These findings may suggest that focusing resources on positive clinical experiences in primary care may be most influential to encourage IM primary care residency graduates to enter the primary care workforce.

The literature has been more mixed regarding the effect of perceived lifestyle in primary care. Although our study shows evidence that primary care residents who pursued primary care expressed more positive perspectives about perceived lifestyle/work hours, other studies have demonstrated that lifestyle concerns, particularly administrative and paperwork concerns, may have deleterious effects on primary care career choice.17

Notably, most primary care residency graduates in our study who practice primary care expressed substantial concern with the administrative burden and demands of clinical work associated with a primary care career. It is possible that the effect of administrative burden assessed through the survey instrument may relate to the administrative burden of their clinical experience or an individual’s own tolerance for administrative burden. While these graduates still chose to pursue a primary care career, this raises concern of potential burnout; this is consistent with other studies.23 Approximately one in six general internists choose to leave internal medicine by mid-career compared to one in 25 internal medicine subspecialists.25 The substantive concerns over burnout, administrative burden, and the demands of primary care clinical work suggest a need for continued innovation in primary care clinical work environments to attract and retain clinicians in the workforce.

Other studies have also noted that supportive primary care faculty role models and peers positively influence selection of primary care careers among medical trainees.17,20,22,24 Of note, physician mentors’ attitudes toward primary care are important regardless of their clinical specialty.17,24 In several ways, our results reaffirm the importance of exemplary faculty and peers to inspire trainees about the honor and joys of serving as a primary care physician.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, we evaluated only graduates of IM primary care residency programs and not categorical IM residency programs. Second, we did not evaluate graduates of other residencies that are associated with primary care such as family medicine and pediatrics. Further study may be warranted to evaluate graduates of such programs. Third, we assessed graduates of only seven internal medicine residency programs. Although we attempted to include programs with variable geographic location and size, this data may not be generalizable to all internal medicine primary care residency programs. Fourth, this is a cross-sectional study so responses regarding past perceptions of training experiences and primary care interest are subject to recall bias. Fifth, while our survey methodology allows for efficient data gathering from a large sample of primary care residency graduates, we acknowledge that this approach limits the details we can gather and further qualitative work may build upon our findings. Sixth, survey data was collected in fall 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic and there may have been changes in residency structures or content due to pandemic effects as well as time since survey collection.

Our study demonstrates factors associated with primary care career choice among IM primary care residency graduates. The results suggest the importance of optimizing the quality of the outpatient continuity clinic experience for residents, including ensuring appropriate multidisciplinary patient support. Cultivating a supportive learning community during training appears to promote enthusiasm about pursuing careers in primary care. Initiatives that mitigate the administrative burden may also help decrease concern for burnout in primary care. These data may compel health system and medical education leaders to explore, advocate for, and implement adaptations that will better support the expansion of the primary care workforce. The health of the population depends on efforts to maintain access to an effective primary care workforce.

References

McCauley L, Phillips RL, Meisnere M, Robinson SK. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care (2021). 2021. https://doi.org/10.17226/25983.

Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. Quantifying the Health Benefits of Primary Care Physician Supply in the United States. Int J Heal Serv. 2007;37(1):111-126. https://doi.org/10.2190/3431-G6T7-37M8-P224.

Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Aff. 2004;23(SUPPL.). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.W4.184

Kravet SJ, Shore AD, Miller R, Green GB, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Health Care Utilization and the Proportion of Primary Care Physicians. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):142-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.021.

Chang C, Stukel TA, Flood AB, Goodman DC. Primary Care PhysicianWorkforce and Medicare Beneficiaries’ Health Outcomes. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2015;305(20):2096-2105.

Pandhi N, Saultz JW. Patients’ perceptions of interpersonal continuity of care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(4):390-397. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.19.4.390.

Pourat N, Davis AC, Chen X, Vrungos S, Kominski GF. In California, Primary Care Continuity Was Associated With Reduced Emergency Department Use And Fewer Hospitalizations. Health Aff. 2015;34(7):1113-1120. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1165.

Sonmez D, Weyer G, Adelman D. Primary Care Continuity, Frequency, and Regularity Associated With Medicare Savings. JAMA Netw open. 2023;6(8):e2329991. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.29991.

Dall T, West T, Iacobucci W. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2018 to 2033. Assoc Am Med Coll. 2020;(June):1–59.

Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs:2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6):503-510. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1431

CP W, DM D. General medicine vs subspecialty career plans among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2241-2247. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.47535.

Stanley M, O’Brien B, Julian K, et al. Is Training in a Primary Care Internal Medicine Residency Associated with a Career in Primary Care Medicine? J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1333-1338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3356-9.

Paralkar N, LaVine N, Ryan S, et al. Career Plans of Internal Medicine Residents From 2019 to 2021. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(10):1166-1167. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.2873.

O’Rourke P, Tseng E, Chacko K, Shalaby M, Cioletti A, Wright S. A National Survey of Internal Medicine Primary Care Residency Program Directors. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1207-1212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04984-x.

Klein R, Alonso S, Anderson C, et al. Delivering on the Promise: Exploring Training Characteristics and Graduate Career Pursuits of Primary Care Internal Medicine Residency Programs and Tracks. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(4):447-453. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00010.1.

O’Rourke P, Tseng E, Levine R, Shalaby M, Wright S. The Current State of US Internal Medicine Primary Care Training. Am J Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.05.006.

DeWitt DE, Curtis JR, Burke W. What influences career choices among graduates of a primary care training program? J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(4):257-261. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00076.x.

Chen D, Reinert S, Landau C, McGarry K. An evaluation of career paths among 30 years of general internal medicine/primary care internal medicine residency graduates. R I Med J (2013). 2014;97(10):50–54.

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Primary Care Policy Center. Definitions. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/johns-hopkins-primary-care-policy-center/definitions. Accessed April 28, 2024.

Peccoralo LA, Tackett S, Ward L, et al. Resident satisfaction with continuity clinic and career choice in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1020-1027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2280-5.

Chen I, Forbes C. Reflective writing and its impact on empathy in medical education: systematic review. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2014;11:20. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2014.11.20

Kryzhanovskaya I, Cohen BE, Kohlwes RJ. Factors Associated with a Career in Primary Care Medicine: Continuity Clinic Experience Matters. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3383-3387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06625-8.

Stepczynski J, Holt SR, Ellman MS, Tobin D, Doolittle BR. Factors Affecting Resident Satisfaction in Continuity Clinic-a Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4469-8.

Long T, Chaiyachati K, Bosu O, et al. Why Aren’t More Primary Care Residents Going into Primary Care? A Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(12):1452-1459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3825-9.

Bylsma WH, Arnold GK, Fortna GS, Lipner RS. Where have all the general internists gone? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(10):1020-1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1349-2.

Funding

Dr. Wright is the Anne Gaines and G. Thomas Miller Professor of Medicine supported through the Johns Hopkins Center for Innovative Medicine, and he is the Mary and David Gallo Scholar for Johns Hopkins’ Initiative to Humanize Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

This work was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in April 2022.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Rourke, P., Tackett, S., Chacko, K. et al. Factors Influencing Primary Care Career Choice: A Multi-Institutional Cross-sectional Survey of Internal Medicine Primary Care Residency Graduates. J GEN INTERN MED (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08846-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08846-z