Abstract

Despite their colossal size and importance in policing, China’s auxiliary police forces have garnered very little research attention. This study attempts to fill our knowledge gap by first describing key features that distinguish the auxiliary police from the regular police in China and their counterparts in Western societies, followed by an empirical investigation of public attitudes toward the auxiliary police in China. Based on survey data collected from a coastal city in China, we reported the general patterns of people’s evaluations of auxiliary officers and assessed whether variables representing institutional trust, media exposure, and neighborhood context are predictive of Chinese attitudes toward the auxiliary police. We found that Chinese citizens rated their local auxiliary officers very positively. Trust in the government and police and known negative reports about the auxiliary police are linked to Chinese’ global satisfaction with the auxiliary police. Trust in the police, exposure to and belief in negative media reports about the auxiliary police, and perception of neighborhood collective efficacy are associated with people’s specific attitudes toward auxiliary officers. Implications for future research and policy are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, China has moved unprecedentedly toward the most authoritarian society, with the police exercising the key role in governmental surveillance, censorship, and punishment of its populace. The 2 million strong regular police force, the so-called People’s Police (minjing in Chinese), assisted by the massive auxiliary police (fujing in Chinese) and the quasi-military People’s Armed Police (wujing in Chinese), is empowered with seemingly unlimited authority and resources to protect the privileges and interests of the Chinese Communist Party. Given the pivotal role of the Chinese police in domestic governance, an increasing number of studies have devoted to analyzing various aspects of policing, with research on public attitudes toward the police as one of the most frequently investigated areas. Relying predominately on public opinion surveys, a vein of recent inquiries has noticeably extended the criminological literature by studying Chinese views on the police along such evaluative measures as general attitudes (Michelson and Read 2011; Zhang et al. 2014), satisfaction (Jiang et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2013), trust or confidence (Han et al. 2017; Hsieh and Boateng 2015; Lai et al. 2010; Sun et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2016), and legitimacy (Liu and Liu 2018; Sun et al. 2017).

This study focuses on public attitudes toward the auxiliary police in China, a group of individuals who play an extremely important role in Chinese policing but receive very little research attention in the existing literature. With a gargantuan number of personnel at least twice the number of the regular police, China’s auxiliary police are salaried employees who are actively involved in law enforcement, order maintenance, and service activities. The similarities and distinctions between China’s auxiliary police and these in Western countries have never been examined in previous research.

Like the volunteer police in the U.S.A. (Dobrin and Wolf 2016), very little is known about the auxiliary police in China. This study extends the policing literature on two fronts. First, it provides an introduction of the auxiliary police covering key functions, distinctive features, and recent challenges, enhancing our understanding about the critical roles as well as the dilemmas associated with the auxiliary police in contemporary China. Such information is imperative to scholars and the public to appreciate how street-level policing is carried out in China and why. Second, to the best our knowledge, no previous study has examined factors related to people’s attitudes toward the auxiliary police in China. Our study enriches the existing literature by assessing the linkages between institutional trust, media exposure, and neighborhood context and people’s assessments of the auxiliary police.

Based on survey data gathered from Xiamen, China, this study attempts to answer two questions. First, what are the general patterns of people’s evaluations of their local auxiliary officers? Second, are variables representing institutional trust, media exposure, and neighborhood context predictive of Chinese evaluations of the auxiliary police? Important implications for future research and policy are expected to be derived from the findings of this study.

China’s Auxiliary Police—The Unavoidable Dilemmas

The word fujing in Chinese literally means “assistants to the police”. Officially speaking, China’s auxiliary police are non-police personnel who are employed, based on each locality’s situations of law and order and the needs of public security, to assist police officers in performing their daily operations and activities (State Council of People’s Republic of China 2016). The history of auxiliary forces in the Communist China can be traced back to the 1960s when the police started utilizing the joint prevention teams formed collaboratively by workers of state-owned enterprises and the police for the purposes of patrol, order maintenance, and crime prevention (Jin and Ding 2015). China’s fast economic growth in the 1980s witnessed a rapid expansion of auxiliary forces to deal with rising crime and disorder problems. The enlarged auxiliary force was seriously plagued by abusive and corrupt behaviors, leading to the dismissal of a large number of auxiliary officers in the early 2000s (Xiong 2014, but see Lo 2012). The move toward retrenchment nonetheless was short lived due chiefly to the chronicle problem of manpower shortage of the police. Beginning in 2009, another wave of recruiting more auxiliary police officers surfaced (Jin and Ding 2015). The auxiliary police have been used continuously as a primary approach to address the pervasive problem of understaffing among police agencies (Lo 2012).

To illustrate some unique features of China’s auxiliary police, Table 1 summarizes the comparisons of three forces, the auxiliary police in Xiamen and the auxiliary forces in two U.S. cities, New York and Los Angeles. Past studies have documented considerable variations among U.S. agencies having volunteer officers (Malega and Garner 2019; Wolf et al. 2016) and across the U.S and U.K. police departments with similar programs (Britton et al. 2018; Pepper and Wolf 2015). We selected New York Police Department (NYPD) and Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) as comparison groups because their auxiliary police programs vary greatly with respect to police power and core functions. In fact, police auxiliaries in NYPD and LAPD stand at opposite ends on the continuum of volunteer policing (Wolf et al. 2016). That is, LAPD’s reserve officers are endowed with full police power and responsibilities as regular officers, whereas NYPD’s auxiliary police have no arrest power and perform principally order maintenance and service activities, with most other police agencies utilizing their volunteers somewhere in between these two large departments (Wolf et al. 2016). Both departments were also chosen as their programs’ essential elements are well articulated and readily available to the public online.

Under the direct supervision of police officers, China’s, including Xiamen’s, auxiliary police are engaged broadly in all sorts of police work including crime investigation, which is similar to LAPD’s level 1 and 2 reserve officers (see Table 1), but it is not the case for NYPD’s auxiliaries whose involvement in police work is normally non-enforcement and non-hazardous in nature. Serving as auxiliary officers in China thus could be a risky occupation as they routinely work side-by-side with police officers to dispose of potentially violent confrontations. On October 2, 2019 in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province, one police officer and one auxiliary officer were shot to death and a second auxiliary officer was critically injured when responding to a domestic violence incident. During recent years, the auxiliary police in China suffered an average death on duty of 100 annually, with an additional 2000 injured (Xinhua News Agency 2016). In 2019, a total of 147 deaths and 5699 injuries were recorded for China’s auxiliary police (Ministry of Public Security, People’s Republic of China, 2020).

No reliable national statistics regarding the size of China’s police auxiliaries is available. A few studies reported an estimated number from two to four million countrywide (e.g., Wang and Huang 2015). Statistics on individual provinces or cities showed an auxiliary officer/police officer ratio ranging from roughly 1.5 to 3.0 (Li et al. 2012; Wang 2016). In Xiamen, there are less than 4500 police officers who are assisted by approximately 10,000 auxiliary officers. It should be pointed out that the ratio is even higher among the neighborhood-level police field stations (the so-called paichusuo) (Song 2017). These numbers clearly indicate that the auxiliary police at their current manpower strength are an indispensable part of street-level policing in China.

Although China’s auxiliary police are not empowered with independent authority to enforce the law, relevant regulations do permit them to assist the police in performing all kinds of policing activities including enforcement actions as long as at least one regular police officer is present at the scene (Xiong 2014). The Chinese police, particularly regarding their street-level operations, have fully taken the advantage of this powerful force. It is common for auxiliary officers to shoulder some of the least desirable assignments (e.g., domestic violence incidents, traffic enforcement, and public protests) in Chinese policing (Jin and Ding 2015). The responding team to 110/emergency calls to the police normally consists of one police officer and at least one, and often more, auxiliary officers. It is fair to stress that China’s auxiliary police are the essential law enforcers on the street. Their omnipresence has eventually established a form of surrogate policing that has never been observed in the Chinese history and rarely been formally acknowledged in the literature.

Like regular police officers, auxiliary officers are street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky 1980), who face a work environment that can be characterized as inadequate resources, ambiguous work goals and expectations, unclear performance measures, and non-voluntary clients. Adding to their job challenges, auxiliary officers are treated as second-class personnel within public security organizations. They are highly localized forces funded entirely by local governments and staffed primarily by local residents. Depending upon economic developments of the jurisdictions and financial situations of local governments, auxiliary officers receive a salary typically no more than half of that of police officers and have limited or no benefits at all. Compared to police officers, auxiliary officers have lower job qualifications, and their rank structures and training are not standardized, varying considerably across jurisdictions. Making things even worse, when police misconduct and abusive behaviors were exposed on social media, auxiliary officers often become the convenient scapegoats for blame to quiet public outcry against the police. High degrees of workload and stress, lack of advancement opportunity, and low levels of compensation and public respect have made high job turnover a common problem among the auxiliary forces (Jin and Ding, 2015).

In addition to comparing Xiamen’s auxiliary police with these in Los Angeles and New York, we also elucidate the dilemmas associated with police auxiliaries in other Western countries, such as Australia (Cherney and Chui 2010, 2011), the Netherlands (Van Steden 2017), and the U.K. (Merrit and Dingwall 2010) and describe similar issues in China. In Australia, for instance, although Queensland’s Police Liaison Officers contributed to better police engagement with ethnically and culturally diverse communities, they faced a dilemma related primarily to conflicting expectations of their accountability to the organization and the greater community (Cherney and Chui 2010). In rural England and Wales, the creation of Police Community Support Officers (PCSOs) allowed the police to rejuvenate some positive aspects associated with the “village bobby” image, but the lack of career development for PCSOs has undermined some potential benefits of the program (Merrit and Dingwall 2010). Like their counterparts in Xiamen, PSCOs are salaried employees, but it should be noted that PSCOs have no law enforcement authority and a decrease in the use of PSCOs due to budget reductions over the past several years has been noted (Leahy et al. 2020).

The existence and widespread use of the auxiliary police have also created dilemmas in Chinese policing. The governmental use of a massive policing manpower (i.e., the auxiliary police) to exercise a heightened social control often runs counter to the public’s expectations to have fair and quality policing on the street. On the one hand, police auxiliaries have effectively alleviated the unbearable pressure of understaffing of police agencies by recruiting young people into workforces as auxiliary officers at a rather low cost (Jin and Ding 2015). On the other hand, the expectation for fair service and quality policing delivered by well-trained and adequately compensated professionals is unlikely to be fulfilled with over-reliance on auxiliary officers. Unfortunately, under the current political climate in China, it seems that a strong wish to maintain social stability and regime legitimacy by all means has overpowered the establishment of professional police forces that serve the interests of all social segments.

No known study has analyzed Chinese attitudes toward the auxiliary police and associated factors of such evaluations. Social media often portrays auxiliary officers as under-appreciated members of the police forces who are regularly disrespected, doubted, and even challenged by neighborhood residents (Wang 2018). Other news reports on misconduct and abusive actions committed by auxiliary officers are also not uncommon, further tarnishing the image of the auxiliary police. In January 2016, the central government issued “The Opinions on Regulating the Management of Auxiliary Police under the Public Security Organizations” aimed at tightening the administration of China’s auxiliary forces (State Council of People’s Republic of China 2016). Some localities have taken up the directive by improving the recruitment, training, evaluation, and compensation of their auxiliary forces (Wang 2018). The roles and functions associated with auxiliary officers, however, remain largely unchanged in recent years.

Predicting Attitudes toward the Auxiliary Police

This study represents a first attempt to assess factors related to Chinese perceptions of the auxiliary police. Three groups of variables, including institutional trust, media exposure, and neighborhood context, were selected as predictors of public attitudes toward the auxiliary police in China. The following sections explain these correlates’ theoretical and empirical relevance to public views on auxiliary officers. Given the paucity of literature pertaining to auxiliary officers, our review on correlates of perceptions draws references predominately from studies on police officers.

Institutional Trust

Institutional trust refers to the extent to which people trust political, legal, and civil institutions to accomplish their expected roles in a satisfactory manner (Hudson 2006). Public trust in political institutions in particular is crucial to the healthy functioning of a government as it forms the legitimacy base of a political system (Easton 1975). High degrees of distrust were found to stimulate greater public engagement in mobilized modes of political participation, such as riots and other anti-government political activities (Seligson 1980), posing significant threats to the stability of domestic governance. In contrast, trust, as an important dimension of police legitimacy, can promote compliance and cooperative behaviors among the public (Tyler 1990).

This study tests whether Chinese trust in governmental institutions can be linked to their attitudes toward the auxiliary police. A few studies conducted in European Union (EU) countries have supported a connection between trust in governmental institutions and public evaluations of the police. For example, conceptually and statistically separating trust in legal institutions (the police and the legal systems) and trust in political institutions (parliament, politicians, and political parties), a study of EU countries found a high degree of correlation between the two types of trust (Schaap and Scheerpers 2014). Using survey data collected from Bulgaria and Romania, another study showed that institutional trust was the strongest predictor of people’s attitudes toward the police in both countries (Andreescu and Keeling 2012). A third study revealed that levels of government corruption were significantly related to the country-level variation in trust in the police (Kaariainen, 2007).

Worthy to mention, social and institutional trust are two most popular types of trust that have been used to predict Chinese attitudes toward the police. Social or interpersonal trust, often conceptualized as consisting of generalized and particularized trust, has been found to be predictive of trust in the Chinese police (Han et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2015; Sun et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2016). Past studies also used trust in neighborhood resident committees as an indicator of institutional trust and found that it is significantly linked to trust in the police (Sun et al. 2012; Sun et al., 2013, 2013b). The association between institutional trust and trust in the police, however, has not been adequately assessed in China. We hypothesize that trust in government and trust in the police are positive related to Chinese attitudes toward the auxiliary police.

It should be noted that conducting survey projects related to institutional trust in an authoritarian setting carries some challenges that could pose threats to the reliability of survey data. For instance, when being asked about their trust in the police, the respondents may not feel comfortable providing honest and accurate answers. While it is difficult to determine the scope and impact of these potential threats, researchers have recognized the issue and come up with methods that could possible mitigate the problem. For example, prior research has found that Chinese expressed highly positive attitudes toward the police when asked about their overall or global satisfaction with trust/confidence in the police using one single item (Lai et al. 2010; Sun et al. 2012; Wu and Sun 2009). Greater variations and more critical evaluations, however, were observed when Chinese were inquired about specific evaluative items, such as police fairness, effectiveness, and integrity (Wu and Sun 2010). These findings point to the need to consider multiple evaluative areas that go beyond a single-item indicator of global attitudes toward the police.

Media Exposure

In this study, media exposure reflects the extent to which people have encountered and believe in negative reports about the auxiliary police in China from major media sources. The influence of the media on public attitudes toward the police in Western societies has been widely reported (e.g., Callanan and Rosenberger, 2011; Kaminski and Jefferis 1998; Weitzer and Tuch, 2006). The relationship between media consumption and public attitudes toward legal authorities is rather complex and shaped by, for instance, the type and content of the media and the frequency of media exposure (Wu 2014). Reports on police misconduct were found to lower public satisfaction with the police (Kaminski and Jefferis 1998; Weitzer 2002). Frequent exposure to such negative news coverage has a particularly detrimental effect on people’s satisfaction with the police and their beliefs in the frequency of police misconduct (Weitzer and Tuch, 2006).

Several studies have assessed the plausible link between media exposure on public perceptions of the police in Chinese societies. As expected, being exposed to and having faith in the truth of negative news about the police were associated with lower ratings of the Chinese police (Sun et al., 2013, 2013b). Similar findings were reported in studies on Taiwanese’ perceptions of the police (Sun et al. 2014; Sun et al. 2016). A comparative study, however, found that the frequency of consumption of television, newspaper, and the Internet did not affect public trust in the police in both China and Taiwan (Wu 2014). Following identical indicators used in previous research (Sun et al. 2014; Sun et al., 2013), this study analyzes the relationships between the frequency of being exposed to negative reports and the degree of believing in such reports and people’s attitudes toward the auxiliary police. It is hypothesized that Chinese who are more frequently exposed to negative reports on media about auxiliary officers tend to express less favorable attitudes toward the auxiliary police. In addition, people who have greater belief in media negative reports on the auxiliary officers are less positive about the auxiliary police.

Neighborhood Context

Neighborhood context refers to the structural and organizational characteristics associated with neighborhoods that individuals reside in. The linkages between neighborhood contextual characteristics and crime and delinquency have long been acknowledged by social disorganization theorists (Sampson and Groves 1989; Shaw and McKay 1942). Albeit still limited in scope, a line of research has found that neighborhood characteristics, such as concentrated disadvantage, racial or minority population, and disorder and crime, are predictive of public attitudes toward the police (Reisig and Parks 2000; Sampson and Jeglum-Bartusch 1998; Wu et al. 2009). This study investigates the association between two neighborhood contextual indicators, collective efficacy and sense of safety, and Chinese attitudes toward auxiliary officers. Collective efficacy signals the degree of local residents’ mutual trust, cohesion, and willingness to intervene when neighbors need help (Sampson et al. 1997). Several past studies conducted in Western countries have shown a positive connection between collective efficacy and public evaluations of the police (Cantora et al. 2019; Kochel 2018; Nix et al. 2015; Wu et al. 2011). Such a linkage was also confirmed by studies based on data from Asian societies, including China (Han et al. 2017), South Korea (Kwak and McNeeley, 2019), and Taiwan (Lai 2016).

A second indicator related to neighborhood context is perceived safety in the neighborhood. The relationship between a sense of safety and public evaluations of the police can be explained using the instrumental model, which posits that the police are instrumental in accomplishing their core mission of preventing people from being victimized and making people feel safe (Jackson and Bradford 2009). If the police are viewed as not fulfilling such expectations, then the public is likely to believe that crime cannot be handled effectively, subsequently lowering their favorable attitudes toward the police. These arguments are in line with key propositions associated with the performance or accountability model of public attitudes toward the police, which contends that the police are accountable for their responsibilities of fighting crime and maintaining order and that their performance shapes people's views on the police (see Skogan 2009). Studies conducted in mainland China and Taiwan reveal inconsistent results, with some reporting a positive link between feelings of safety and perceptions of the police (Sun et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2012), whereas others suggesting a non-significant relationship (Sun et al., 2013, b).

Given that a large portion of China’s auxiliary police are assigned to neighborhood field stations to assist frontline officers, the respondents’ assessments of auxiliary officers could be a reflection of their views on the conditions of collective efficacy and safety within the neighborhood. Based on the existing literature, we hypothesize that higher degrees of collective efficacy and sense of safety are likely to be accompanied by more positive attitudes toward the auxiliary police.

Methodology

Data Collection and Sample

This study used survey interview data obtained from Xiamen in southeastern Fujian Province of China during the fall of 2018. Xiamen is an economically and culturally well-developed coastal city that has been consistently rated as one of the best cities to live in China. With a population of over four million, Xiamen is divided into six administrative districts. The research project was carried out in the most populous and urbanized district in the city due mainly to the researchers’ connection to local officials, familiarity with the area, and frequent police-citizen encounters that occur in this busy district. Depending upon a survey instrument that consisted of 120 items, a team of researchers from a local university conducted face-to-face interviews with selected local residents in the sample district.

The study sample was selected from the district through a multiple-stage process. First, within the 10 street blocks in the district, 16 neighborhood residents’ committees (NRCs) were randomly selected from a total of 97 NRCs based on the population size of each street block. Specifically, 1 NRC was chosen from each of the 4 small-population street blocks, 2 NRCs were selected from each of the 3 mid-population-size street blocks, and 3 NRCs were chosen from each of the 2 large-population street blocks as the primary sampling units (PSUs). Second, 50 households were randomly selected from each of the 16 PSUs, resulting in an initial sample of 800. Finally, within each sampled household, a resident who was at least 18 years old and willing to participate in the project was interviewed. During the data collection process, 45 selected samples declined to participate, resulting in a response rate of 94.6%. Supplementary respondents were randomly chosen to reach the target sample of 800. The average time to finish an interview was 40 min. All respondents were informed about the principles of voluntariness and anonymity prior to the interview.

Among the 800 collected surveys, 4 were deemed unusable due to large amounts of missing data. Another 30 respondents were dropped from the analysis due to missing values on key study variables, leading to a final sample of 766 respondents for this study. As shown in Table 2, the final sample was comprised of 52% female and 48% male respondents. The average age of the respondents was 42 and roughly one-third of them had some college or higher education background. Slightly over one-third of the respondents had a nonlocal hukou (household registration).

Variables

Recognizing the potential problem of only using a single-item indicator in measuring people’s attitudes toward the police, two dependent variables were constructed to represent people’s global attitudes and specific attitudes toward the auxiliary police separately (see Brandl et al. 1994; Zhao and Ren 2015). People’s global attitudes were measured through a single item asking the respondents’ overall satisfaction with their local auxiliary police. The response categories of the item included: highly dissatisfied (1), dissatisfied (2), satisfied (3), and highly satisfied (4). Preliminary analysis showed that the assumption of the parallel lines for ordered logistic regression was violated. The measure thus was recoded into a dummy variable, with 0 representing “highly dissatisfied” or “dissatisfied” and 1 signaling answers of “satisfied” or “highly satisfied.”

An additive scale reflecting people’s attitudes toward the auxiliary police was also constructed as the second dependent variable in the regression analysis. As displayed in Table 3, the scale was made up by seven items that tapped into people’s supportive views on the roles, functions, trustworthiness, and respectability of the auxiliary police. Although these items reflect different (but related) conceptual dimensions, they loaded onto a single factor with good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88). We thus employed a broad term “attitudes” to encompass these different dimensions. A higher score on the scale indicates a higher level of favorable attitudes toward the auxiliary police. These seven items were used separately to demonstrate the general patterns of public attitudes toward auxiliary officers.

Three groups of independent variables were constructed, including institutional trust, media exposure, and neighborhood context. Institutional trust was represented by two additive scales, indicating trust in government and trust in police. Trust in the government included six items measuring respondents' trust in different levels of government, ranging from the central government to the village committee. Another six items were used to reflect the respondents’ degrees of trust in the regular police. Cronbach’s alpha associated with the two trust scales is 0.93 and 0.91, respectively, implying high internal consistency.

The second group of independent variables, tapping into media exposure, included two single-item variables. The respondents were asked about “how often you have heard or read news (from radios, TVs, newspapers, and the Internet) about misconduct by the auxiliary police (such as brutality, abusive languages, and lack of professionalism)” (1 = never; 2 = rare, 3 = sometimes, and 4 = often) and “do you believe the negative news about the auxiliary police reported by the media (1= don’t believe; 2=slightly don’t believe; 3=believe; 4=strongly believe).” A higher value thus suggests a higher level of exposure to and belief in negative media reports about the auxiliary police.

The last category of independent variable is comprised of two neighborhood contextual characteristics, collective efficacy and neighborhood safety. The former is a 5-item additive scale and the latter a 4-item scale signaling the levels of perceived collective efficacy and safety in the respondents’ neighborhoods. Both scales have good internal consistency, registering a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 and 0.81, respectively.

Two groups of variables measuring the respondents’ familiarity and previous contact with the auxiliary police and background characteristics were controlled. Two items asking whether the respondents were familiar with the auxiliary police’s recruitment and duties (1 = not familiar at all, 4 = very familiar) were combined to form the familiarity scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89). The respondents were also inquired about whether they have family members and relatives or friends serving as the auxiliary police (no = 0, yes = 1). A third control variable signals whether the respondent had contact with the auxiliary police for any reason over the past year (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Lastly, demographic characteristics include gender (male = 1), age (measured in years), educational attainment (elementary school and under = 1, graduate school and above = 6), self-perceived SES (compared to surrounding families, would you say your family’s economic status is 1 = much worse, much better = 5), government or party employee (no = 0, yes = 1), and non-local hukou (local hukou = 0, nonlocal = 1). Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics for all variables used in regression analysis. Multi-collinearity among the independent and control variables was not a problem as the variance inflation factors (VIFs) were all below 1.5 and the highest correlation between any two predictors was 0.45 (between trust in government and trust in police).

Results

To address our first question about the general patterns of public evaluations of the auxiliary police, we report the percentage distributions associated with the participants’ responses regarding their overall satisfaction with as well as their attitudes toward the auxiliary police. As shown in Table 4, Chinese satisfaction with the auxiliary police is highly positive, which is somewhat unexpected. Nearly 85% of the respondents reported they were “satisfied” with their local auxiliary police and another 6.5% of the respondents reported “highly satisfied.” Adding them together, more than 90% of the Chinese respondents rendered a satisfactory rating of their local auxiliary officers.

Looking at the seven items used to construct our dependent variable, attitudes toward the auxiliary police, Chinese rendered high ratings of their local auxiliary officers. With the only exception of the item “Auxiliary police serve as the bridge to connect the police and the public”, more than 80% of the participants chose “somewhat agree”, “agree,” or “highly agree” as their responses to the questions. As indicated by the response mean (4.74), the item stating that “Auxiliary police are important forces to assist the police and stabilize social order” received the highest rating, with 52.2% of the responses expressing “agree” and another 15.5% conveying “highly agree.” The statement that “People should support the work of auxiliary police” is also highly rated (mean = 4.62), registering a percentage of 46.2 and 11.6 for “agree” and “highly agree,” respectively. With respect to the item asking about police trustworthiness (mean = 4.36), the category “somewhat agree” received 43.9% of responses, followed by 35.4% for “agree” and 8.6% for “highly agree.” Among the seven items, the question stating “Auxiliary police serve as the bridge to connect the police and the public” received a lowest mean score of 4.14, which is still above the median point of 3.5. Although these ratings for specific items remain positive, they show greater variations across different items and on average more critical assessments of the auxiliary police, compared to the score for the global satisfaction variable.

Table 5 reports the regression results of public global and specific attitudes toward the auxiliary police. The results indicate that people’s global and specific attitudes toward the auxiliary police are linked to a somewhat different set of predictors. Consistent with our expectations, both forms of institutional trust are significantly related to global attitudes toward the auxiliary police, with views of the government and the police trustworthiness associated with greater satisfaction with the auxiliary. As predicted, knowing negative reports about the auxiliary police reduced people’s satisfaction with the force. Believing in media reports is not predictive of overall satisfaction with the auxiliary police, so do the two neighborhood variables of collective efficacy and neighborhood safety. Only one control variable is connected to global attitudes toward the auxiliary police. People who are more familiar with the recruitment policies and duties of the auxiliary police are more likely to express satisfaction with the force.

Switching to specific attitude model, among the two trust variables, trust in the police is a significant and the strongest predictor of people’s attitudes toward the auxiliary police. Consistent with our hypothesis, those who rated the regular police as trustworthy are more likely to express positive evaluations of the auxiliary police. Unlike the results in the global attitudes model, trust in the government is not significantly related to attitudes toward police auxiliaries.

Although only one media variable is predictive in the global attitudes model, both media exposure variables exerted a significant connection to the specific attitudes variable. Consistent with our expectations, Chinese who have been exposed to negative reports of the auxiliary police and who tended to believe such reports are true are more inclined to rate the auxiliary police less favorably. While neighborhood variables are not significant in the global attitude model, one of the two neighborhood contextual characteristics is significantly linked to specific attitudes toward the auxiliary police. As hypothesized, residents who viewed their neighborhood as having higher levels of collective efficacy demonstrated more positive assessments of auxiliary officers. The second neighborhood contextual variables, sense of safety, is not predictive of public opinions on auxiliary officers.

Two of the control variables were also predictive of assessments of the auxiliary police. People who were familiar with the auxiliary police or have family members, relatives, or friends serving as auxiliary officers rated the force more positively. None of the demographics were a significant predictor of attitudes toward the auxiliary police. The explanatory variables together accounted for 31% of the variation in Chinese evaluations of the auxiliary police.

Discussion

This study represents a pioneering assessment of an important but severely under-investigated group within China’s public security organizations, the auxiliary police. We pointed out that the auxiliary force’s massive size and involvement in all aspects of police work have made them crucial members of China’s blanket security aimed at monitoring and handling any perceived threats to the status quo. Auxiliary officers’ vital roles in China nonetheless are irreconcilable with their secondary status in qualifications, training, prestige, and compensation within police agencies. They face a difficult working environment and are subject to a disadvantageous social status. It seems that, however, their disadvantages did not automatically transmit into unfavorable public opinions.

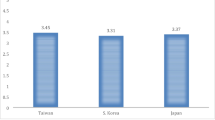

Our finding is largely in line with the results from past studies on the Chinese police which have consistently shown that the majority of Chinese people rated the police favorably, with approximately 60 to 70% of respondents viewing the police as satisfactory or trustworthy (for example, see, Jiang et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2012; Wu and Sun 2009). Our analysis found that the auxiliary police received high levels of support from urban dwellers, with more than 90% of the respondents rating them satisfactorily. The auxiliary police in Xiamen appear to receive even more support from the public than the regular police, as indicated by a prior study that used an identical evaluative item to study Chinese regular police. Specifically, Sun et al. (2013) reported a mean satisfaction score of 2.89 on the police in rural and urban China, lower than the 2.97 mean score of satisfaction found in this study.

Although our data do not allow us to offer empirical explanations to account for such a high satisfactory level of the auxiliary police, two possible explanations come to mind. First, despite an increasingly difficult working environment (Scoggins and O’Brien 2016), there has been little media reports on police abusive and corruptive behavior in Xiamen over the past few years. Overly positive evaluations might actually reflect satisfactory performance delivered by the city police forces including the auxiliary police (Sun et al., 2012). Second, aspects of the authoritarian culture may promote Chinese respondents’ positive attitudes toward the auxiliary police, including the traditional values of respect for and deference to legal authorities and avoidance of conflicts including refraining from criticizing the authority (Shi 2001; Wu et al. 2012). More research on public assessments of the auxiliary police is warranted to uncover factors related to such evaluations.

Regarding the predictors of people’s global and specific attitudes toward police auxiliaries, the results support most of our hypotheses. One exception is that trust in the government, albeit predictive of people’s overall satisfaction, is not linked to respondents’ specific attitudes toward the auxiliary police. While past studies suggest a positive linkage between trust in political institutions and attitudes toward the police (Andreescu and Keeling 2012; Schaap and Scheerpers, 2014), such a connection does not appear to extend to the auxiliary police, who may be considered by the public more as civilian authority than governmental authority. Consistent with our expectation, we discovered a significant connection between trust in the police and more favorable global and specific attitudes toward auxiliary officers. It is worthwhile to point out that the correlation between the trust in the police and the global and specific attitudes variables is not excessively high (r = 0.37 and 0.46, respectively), suggesting that while there is an intertwined nature of attitudes toward the traditional officers and the auxiliary officers, the survey respondents were able to, to a certain degree, distinguish between the two groups and have somewhat differential attitudes toward them. Using comparable data collected from both groups, future research should continue to explore relevant factors that underlie the similarities and possible distinctions regarding public evaluations of both groups of officers.

We also found that the two variables representing media influences, particularly knowing about negative reports, are closely related to people’s views on auxiliary officers. Consistent with findings from previous studies (Sun et al. 2014; Sun et al., 2013; Wu 2014), negative messages carried on news media as well as believing in such reports are likely to be crystalized in people’s unfavorable attitudes toward the auxiliary police. Although the media, particularly new forms of social media, have been widely viewed as one of the most powerful influencers of public opinion, its connection to public views on the auxiliary officers remains under-analyzed in China. More research efforts are needed to, for example, distinguish among different types of media and investigate their relationships with people’s attitudes toward the auxiliary police. Efforts are also needed to assess the content of different media types on their reports of auxiliary officers.

Both neighborhood variables are not predictive of people’s overall satisfaction with the auxiliary police, but one characteristic of neighborhood context, collective efficacy, was found to be linked to attitudes toward auxiliary officers, with residents in neighborhoods with higher levels of cohesion, mutual trust, and willingness to intervene for the common good reporting more support for the auxiliary police. This finding does not come as a surprise as neighborhoods that have positive informal relationships tend to also see positive relationships with formal social control institutions, such as the police, in Western countries (Wu et al. 2011). This positive connection may be even stronger in China as the Chinese frontline officers, including auxiliary officers, operate from neighborhood field stations and collaborate closely with local residents and resident committees. Officers’ community member status and heavy involvement in neighborhood affairs could afford them with many opportunities to participate in various community building efforts and programs, which is likely to improve police–community relations and foster strong bonds and rapport between officers and residents. Collective efficacy and other neighborhood structural and organizational features, such as concentrated disadvantage, percent migrant population, and density of civic engagement, ought to be considered in future research of public assessments of the police.

The second neighborhood variable in our analysis, neighborhood safety, is not predictive of respondents’ specific evaluations of the auxiliary police. This finding is not completely surprising given that past findings are less than consistent with respect to the relationship between perceived neighborhood safety and public assessments of the police (see Wu et al. 2012 and Sun et al., 2013). A possible explanation of this finding is that the majority of Chinese cities, including our study site, have relatively low crime rates with few crime hot spots, leading to little variation in local residents’ perceptions of neighborhood safety. Given that the available findings are equivocal, future research should continue to investigate the potential linkage between perceived neighborhood safety and public attitudes toward the auxiliary police.

This preliminary study has a few limitations that can be improved in future endeavors. First, our survey data were gathered from a group of randomly selected respondents from the coastal city of Xiamen in South China. Although the auxiliary police system in this city is similar to those in other comparable cities, our findings may not be generalized to localities of different geographic and population sizes and with different degrees of economic development. Caution therefore needs to be exercised when applying our findings to other jurisdictions. More studies using diverse samples from different areas of China should be used to further test people’s attitudes toward the auxiliary police. Second, our dependent variable of global attitudes was constructed based on a single item, which is more prone to produce simplistic assessments of social phenomena (Hudson and Kuhner 2010). Meanwhile, although our specific attitudes variable signals multiple evaluative areas (e.g., role, function, trustworthiness, and respectability), future research should tap into additional aspects of public attitudes toward the auxiliary police, such as distributive justice, procedural justice, lawfulness, and effectiveness. Finally, labeled as neighborhood contextual variables, collective efficacy and sense of safety employed in this study are individual-level measures. Using neighborhood contextual variables in individual-level analyses could be problematic as, for example, respondents who are naturally nested in a same neighborhood are often correlated to each other in certain ways. Multi-level statistical approaches should be utilized to properly assess the connections between neighborhood contexts and residents’ attitudes toward the auxiliary police.

Our findings bear some implications for policy. Public attitudes toward the auxiliary police are not stand-alone phenomena but rather highly intertwined with public trust in the police. This connection sends a clear message to police administrators that they should attach similar values to improving the performance of auxiliary officers as to that of sworn officers. Meanwhile, cultivating the image of police trustworthiness is likely to promote positive attitudes toward all segments within the public security organizations. Police agencies should encourage efforts, such as fair and just treatments toward the citizenry, that are likely to enhance public views on police trustworthiness (Tyler 1990).

Given that both media variables are influential, another area that requires more attention from government officials and police administrators is responding appropriately to media reports. Despite tight governmental control over social media, it is nearly impossible to completely or constantly cover up negative reports related to the police. The best strategy to minimize the damage is to have a timely response, regardless of the accuracy of the report. The public has the right to know the truth and the police have the obligation to provide it. Finally, police forces should continue to promote community policing programs designed to build healthy and strong neighborhoods. Playing an active role in promoting mutual trust and cohesion among urban residents should be one of the priorities in police-initiated activities. Neighborhoods with strong collective efficacy benefit both local residents and police officers.

References

Andreescu, V., & Keeling, D. (2012). Explaining the public distrust in police in the newest European Union countries. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 14, 219–245.

Brandl, S., Frank, J., Worden, R., & Bynum, T. (1994). Global and specific attitudes toward the police: disentangling the relationship. Justice Quarterly, 11, 119–134.

Britton, I., Wolf, R., & Callender, M. (2018). A comparative case study of reserve deputies in a Florida sheriff’s office and special constables in an English police force. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 20, 259–271.

Callanan, V., & Rosenberger, J. (2011). Media and public perceptions of the police: examining the impact of race and personal experience. Policing and Society, 21, 167–189.

Cantora, A., Wasileski, G., Iyer, S., & Restivo, L. (2019). Examining collective efficacy and perceptions of policing in East Baltimore. Crime Prevention & Community Safety, 21, 136–152.

Cherney, A., & Chui, W. (2010). Police auxiliaries in Australia: police liaison officers and dilemmas of being part of the police extended family. Policing and Society, 20, 280–297.

Cherney, A., & Chui, W. (2011). The dilemmas of being a police auxiliary: an Australian case study of police liaison officers. Policing: A Journal of Policy & Practice, 5, 180–187.

Dobrin, A., & Wolf, R. (2016). What is known and not known about volunteer policing in the United States. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 18, 220–227.

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science, 5, 444–445.

Han, Z., Sun, I., & Hu, R. (2017). Social trust, neighborhood cohesion, and public trust in the police in China. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 40, 380–394.

Hsieh, M., & Boateng, F. (2015). Perceptions of democracy and trust in the criminal justice system: a comparison between mainland China and Taiwan. International Criminal Justice Review, 25, 153–173.

Hu, R., Sun, I., & Wu, Y. (2015). Chinese trust in the police: the impact of political efficacy and participation. Social Science Quarterly, 96, 1012–1026.

Hudson, J. (2006). Institutional trust and subjective well-being across the EU. Kyklos, 59, 43–62.

Hudson, J., & Kuhner, S. (2010). Beyond the dependent variable problem: The methodological challenges of capturing the productive and protective dimensions of social policy. Social Policy and Society, 9, 167–179.

Jackson, J., & Bradford, B. (2009). Crime, policing, and social order: on the expressive nature of public confidence in policing. British Journal of Sociology, 60, 493–521.

Jiang, S., Sun, I., & Wang, J. (2012). Citizens’ satisfaction with police in Guangzhou, China. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 35, 801–821.

Jin, Y., & Ding, Y. (2015). An analysis of current auxiliary police system in China. Journal of People’s Public Security University of China (Social Science Edition), 175, 108–118.

Kaariainen, J. (2007). Trust in the police in 16 European countries. European Journal of Criminology, 4, 409–435.

Kaminski, R., & Jefferis, E. (1998). The effect of a violent televised arrest on public perceptions of the police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, (21), 683–706.

Kochel, T. (2018). Police legitimacy and resident cooperation in crime hotspots: effects of victimisation risk and collective efficacy. Policing and Society, 28, 251–270.

Kwak, H., & McNeeley, S. (2019). Neighbourhood characteristics and confidence in the police in the context of South Korea. Policing and Society, 29, 599–612.

Lai, Y. (2016). College students’ satisfaction with police services in Taiwan. Asian Journal of Criminology, 11, 207–229.

Lai, Y., Cao, L., & Zhao, J. (2010). The impact of political entity on confidence in legal authorities: a comparison between China and Taiwan. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 934–941.

Leahy, D., Pepper, I. & Light. P. (2020). Recruiting police support volunteers for their professional knowledge and skills: a pilot study. Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles. Online first at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0032258X20914676, .

Li, M., Lu, Y., & Yuan, C. (2012). The difficulties and future directions of managing the auxiliary police: an investigation of the current situation of the auxiliary police in Jiangsu. Policing Studies, 216, 78–88.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public services. New York: Russell.

Liu, S., & Liu, J. (2018). Police legitimacy and compliance with the law among Chinese youth. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62, 3536–3561.

Lo, S. (2012). The changing context and content of policing in China and Hong Kong: policy transfer and modernization. Policing and Society, 22, 185–203.

Malega, R., & Garner, G. (2019). Sworn volunteers in American policing, 1999-2013. Police Quarterly, 22, 56–81.

Merrit, J., & Dingwall, G. (2010). Does plural suit rural? Reflections on quasi-policing in the countryside. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 12, 388–400.

Michelson, E., & Read, B. (2011). Public attitudes toward official justice in Beijing and rural China. In M. Woo, M. Gallagher, & M. Goldman (Eds.), Chinese justice: civil dispute resolution in contemporary China (pp. 169–203). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ministry of Public Security, People’s Republic of China (2020). In visiting frontline officers in Anhui, Zhao Kezhi stressed the importance of maintaining the good well and creating a healthy and stable society. Accessed on January 13, 2020 at https://www.mps.gov.cn/n2253534/n2253535/c6858225/content.html.

Nix, J., Wolfe, S., Rojek, J., & Kaminski, R. (2015). Trust in the police: the influence of procedural justice and perceived collective efficacy. Crime & Delinquency, 61, 610–640.

Pepper, I., & Wolf, R. (2015). Volunteering to serve: an international comparison of volunteer police officers in a UK North East Police Force and a US Florida Sheriff’s Office. The Police Journal: Theories, Practice, and Principles, 88, 209–219.

Reisig, M., & Parks, R. (2000). Experience, quality of life, and neighborhood context: a hierarchical analysis of satisfaction with police. Justice Quarterly, 17, 607–630.

Sampson, R., & Groves, W. (1989). Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 774–802.

Sampson, R., & Jeglum-Bartusch, D. (1998). Legal cynicism and (subcultural?) tolerance of deviance: the neighborhood context of racial differences. Law and Society Review, 32, 777–804.

Sampson, R., Raudenbush, S., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924.

Schaap, D., & Scheerpers, P. (2014). Comparing citizens’ trust in the police across European countries: as assessment of cross-country measurement equivalence. International Criminal Justice Review, 24, 82–98.

Scoggins, S., & O’Brien, K. (2016). China’s unhappy police. Asian Survey, 56, 225–242.

Seligson, M. (1980). Trust, efficacy and modes of political participation: a study of Costa Rican peasants. British Journal of Political Science, 10, 75–98.

Shaw, C., & McKay, H. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press.

Shi, T. (2001). Cultural values and political trust: a comparison of the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan. Comparative Politics, 33, 401–419.

Skogan, W. (2009). Concern about crime and confidence in police: reassurance or accountability? Police Quarterly, 12, 301–308.

Song, M. (2017). On system of auxiliary police’s participation in law enforcement in China’s public security organization. Journal of Sichuan Police College, 29, 37–42.

State Council of the People’ Republic of China. (2016). Opinions on regulating the management of auxiliary police under the public security organs. Accessed on January 8, 2020 at http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2016-11/29/c_1120015347.htm.

Sun, I., Hu, R., & Wu, Y. (2012). Social capital, political participation, and public trust in police in urban China. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 45, 87–105.

Sun, I., Wu, Y., & Hu, R. (2013). Public assessments of the police in rural and urban China: a theoretical extension and empirical investigation. British Journal of Criminology, 53, 643–664.

Sun, I., Hu, R., Wong, D., He, X., & Li, J. (2013b). One country, three populations: trust in police among migrants, villagers, and urbanites in China. Social Science Research, 42, 1737–1749.

Sun, I., Jou, S., Hou, C., & Chang, Y. (2014). Public trust in the police in Taiwan: a test of instrumental and expressive models. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 47, 123–140.

Sun, I., Wu, Y., Triplett, R., & Wang, S. (2016). Media, political party orientation, and public perceptions of police in Taiwan. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 39, 694–709.

Sun, I., Wu, Y., Hu, R., & Farmer, A. (2017). Procedural justice, legitimacy, and public cooperation with police: does western wisdom hold in China? Journal of Research on Crime and Delinquency, 54, 454–478.

Sun, I., Han, Z., Wu, Y., & Farmer, A. (2019). Trust in police in rural China: a comparison between villagers and local officials. Asian Journal of Criminology, 14, 241–258.

Tyler, T. (1990). Why people obey the law. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Van Steden, R. (2017). Municipal law enforcement officers: towards a new system of local policing in the Netherlands. Policing and Society, 27, 40–53.

Wang, Q. (2016). The evaluation, training and encouragement of auxiliary police under public security reform. Journal of Hebei Vocational College of Public Security Police, 16, 78–81.

Wang, S. (2018). Why the “Shenzhen model” of auxiliary police reform has earned the appraisal of leaders of central government? Accessed on January 8, 2020 at http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2018-08-19/doc-ihhxaafy8155498.shtml.

Wang, N., & Huang, Z. (2015). Thoughts on how to improve the management system of the auxiliary police. Journal of Jiangxi Police Institute, 3(2015), 21–23.

Weitzer, R. (2002). Incidents of police misconduct and public opinion. Journal of Criminal Justice, 20, 397–408.

Weitzer, R., & Tuch, S. (2006). Race and policing in America: conflict and reform. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wolf, R., Holmes, S., & Jones, C. (2016). Utilization and satisfaction of volunteer law enforcement officers in the office of the American sheriff: An exploratory nationwide study. Police Practice and Research, 17, 448–462.

Wu, Y. (2014). The impact of media on public trust in legal authorities in China and Taiwan. Asian Journal of Criminology, 9, 85–101.

Wu, Y., & Sun, I. (2009). Citizen trust in police: the case of China. Police Quarterly, 12, 170–191.

Wu, Y., & Sun, I. (2010). Perceptions of police: an empirical study of Chinese college students. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 33, 93–113.

Wu, Y., Sun, I., & Triplett, R. (2009). Race, class or neighborhood context: which matters more in measuring satisfaction with police? Justice Quarterly, 26, 125–156.

Wu, Y., Sun, I., & Smith, B. (2011). Race, immigration, and policing: Chinese immigrants’ satisfaction with police. Justice Quarterly, 28, 745–774.

Wu, Y., Poteyeva, M., & Sun, I. (2012). Public trust in police: a comparison between China and Taiwan. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 36, 189–210.

Wu, Y., Sun, I., & Hu, R. (2016). Public trust in the Chinese police: the impact of ethnicity, class, and Hukou. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 49, 179–197.

Xinhua News Agency. (2016). China issues rules to regulate auxiliary police. Accessed on January 8, 2020 at http://www.china.org.cn/china/2016-11/30/content_39815930.htm.

Xiong, Y. (2014). Thinking about the construction of auxiliary police under the background of police practice reform in China: a comparative approach of the auxiliary police system and police practice reform in England and Hong Kong in China. Journal of People’s Public Security University of China (Social Science Edition), 170(4), 1–16.

Zhao, J., & Ren, L. (2015). Exploring the dimensions of public attitudes toward the police. Police Quarterly, 18, 3–26.

Zhang, H., Zhao, R., Zhao, J., & Ren, L. (2014). Social attachment and juvenile attitudes toward the police in China: bridging eastern and western wisdom. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 51, 703–734.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human Animal and Informed Consent

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, I.Y., Wu, Y. & Hu, R. Public Attitudes toward Auxiliary Police in China: a Preliminary Investigation. Asian J Criminol 16, 293–312 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09333-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09333-0