Abstract

This study examines how residents from a high-crime, high-poverty neighborhood in East Baltimore interact with one another, participate in their community, and perceive police. Using community surveys collected from 191 respondents, the study empirically measures collective efficacy, community participation, and police services and encounters. We predict that high levels of collective efficacy lead to more positive perceptions of police and an increased willingness to work with law enforcement. The results indicate that neighborhood trust is an important factor in shaping a community’s overall perception of police. Furthermore, older residents who own their homes are more likely to report a more positive perception of police, specifically police response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The association between place and crime has been the subject of political and social research for most of this century, giving rise to the importance of the neighborhood and the community. While the discussion of place and crime is not new, the responses to the variation in crime in spaces have continued to be an evolving debate. One such response gaining recent momentum through targeting place has been neighborhood and community revitalization initiatives that present a multifaceted approach to fighting crime and disorder. As cited in a 2011 White House report, revitalization efforts are beneficial in that they try to not only engage important stakeholders within a community, but also involve community members themselves, providing a more holistic approach to crime fighting.

The subject of this paper is a high-crime neighborhood located in Baltimore City, which has one of the highest homicide rates in the USA, making this city an area ripe for crime control and revitalization efforts. This research paper is part of a larger community revitalization initiative funded by the US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance. In 2012, the City of Baltimore received a Byrne Criminal Justice Initiative grant (BCJI) to concentrate research efforts and revitalization strategies in one neighborhood in East Baltimore. The BCJI sets out to use data and research to guide community improvement projects, while involving neighborhood residents and community stakeholders in the process. For 3 years, researchers, residents, and community groups engaged in gathering data and implementing projects to improve the area. One of the key objectives of the BCJI was to improve the level of engagement of residents in neighborhood activities. In an effort to capture engagement and involvement, a community survey was conducted in 2015 and 2016. The survey was aimed at understanding how people interact with one another, participate in the community, and perceive safety and police services. The survey also included measures of collective efficacy.

The citizen’s assessment of the police differs considerably across social groups and it is often impacted by macro-level factors such as poverty and unemployment. In addition to poverty and unemployment, Baltimore has one of the largest murder rates in the USA and police–citizen relations are often associated with anger and impediments of citizen’s trust and support for police for at least three decades. The number of violent crimes, including the homicide rates, and an ongoing debate over racial bias in policing, continuously underscored the importance of mutual trust between police and the people in Baltimore they serve.

Consequently, the main purpose of this study is to present findings from the community survey, specifically to assess attitudinal differences among neighbors in East Baltimore toward community policing, police response to citizens, police–citizen encounters, and satisfaction with the police services in the neighborhood. This study will conclude with recommendations on how to enhance resident involvement and collective efficacy.

Literature review

The association between crime and place first gained momentum in the USA as a group of scholars began to examine crime in Chicago (Burgess 1925; Thrasher 1927; Shaw and McKay 1942). Later coined as the “Chicago School of thought,” the overall premise is that certain characteristics of the urban landscape give rise to crime and disorder, but make important distinctions between structural and social variables of an area (Burgess 1925; Thrasher 1927; Shaw and McKay 1942). Specifically, Shaw and McKay (1942) assert that the urban community has three common characteristics that result in crime, including low economic status, high residential turnover, and population diversity. Urban communities with high poverty tend to attract the poorest of residents, including immigrant groups. The urban poor often have unstable housing and move between high-poverty areas. The instability of residents and their cultural clash create communities that are “socially” disorganized and thus less unified. So while not ignoring the fact that economic opportunity and the means of available funds can be crucial to solving some of the problems plagued by urban communities, the social disorganization theory highlights the importance of the presence of social interaction and the social underpinnings of a community by arguing that the social activity of a community can serve to mediate the existence of disorder and crime.

Wilson and Kelling (1982) argue that the physical landscape of an area, coupled with the activities of community members, can result in more crime by informally communicating what is acceptable and what is not. As such, their Broken Windows theory argues that the presence of social and physical disorder such as loitering, substance use, graffiti and litter, abandoned buildings, and other such incivilities matter because it enables criminals to see these areas as attractive spots to commit crime, as residents are perceived as unwilling to address inappropriate behaviors. The theory goes on to explain that even minor forms of disorder, such as loitering and graffiti, can have a detrimental impact, so long as the activities are able to go on without interference. This theory draws on earlier work by Reiss (1971), who used systematic social observations to discover that residents and guests of a community will tune into the informal rules or norms of an area when certain behaviors remain unchecked. For example, if residents simply throw their trash on the street and no resident or policing agent does anything, replication of that behavior is likely to follow (thus becoming the new norm). In contrast, the opposite is communicated if a resident of that community was to scold someone who is throwing their trash while walking by. These earlier theories all imply a call for action among residents to mobilize and present a unified front in order to control crime and disorder in their neighborhoods.

Acting as a force against disorder, the social control theory, when applied at the neighborhood and community level, is defined as the ability of residents within a neighborhood to realize and hold common values as well as to act to regulate and control that behavior (Janowitz 1975). Sampson and Raudenbush (1999) break down social control into formal (by policy and the courts) and informal (by residents themselves) control. Informal social control is not only the shared values to control antisocial behavior in a community, but their willingness to intervene against disorderly behavior. Intervention by residents can be achieved either by direct intervention by that resident (e.g., telling a resident not to throw trash), by forming a group of residents (e.g., having a few people discourage littering), or by engaging and calling formal authorities (e.g., the police by 911 or 311). Sampson et al. (1997) separate individual efficacy or action and neighborhood efficacy or action. While a certain resident may be likely to act as an individual, at the neighborhood level, there needs to be a shared goal of preventing antisocial behavior, as well as mutual trust that neighbors will act as a united front when needed.

The importance of social ties and bonding to control deviance and crime is explained by the term collective efficacy (Bandura 1975), which is defined as the relationships of a group that lead to trust and the shared expectation to intervene and control behaviors within an environment (Sampson et al. 1997; Sampson and Raudenbush 1999). While collective efficacy can be applied to different social groups such as work or sports (Zaccaro et al. 1995), analyzing this term as it applies to a neighborhood or community has created a wealth of research that explored this notion more fully (Sampson et al. 1997). Sampson et al. (1997) tested this theory in 343 Chicago neighborhoods using a paper survey that measured the likelihood of action regarding varying behaviors including monitoring children playing, intervening in truancy and loitering by teen groups, and acting when individuals are “exploiting or disturbing public space” (Sampson et al. 1997, p. 918). They found that concentrated disadvantage, high immigrant populations, and residential instability explained 70% of the difference in collective efficacy among the sampled neighborhoods. However, collective efficacy mitigated a “substantial” portion of residential instability and disadvantage with respect to violence (p. 923).

Sampson and Raudenbush (1999) further analyzed the presence of informal control in 196 Chicago neighborhoods to measure physical and social disorder. They found that while structural characteristics such as poverty and mixed land use were associated with disorder, collective efficacy predicted lower observed disorder even after controlling for both of these variables. Most of the earlier works on collective efficacy have measured this phenomenon using hypothetical questions about what a resident would do if confronted with a situation to control antisocial behavior (Sampson et al. 1997).

Collective efficacy research has expanded to examining which neighborhood variables can contribute to the formation of social bonds and relationships within communities. For example, commitment to a neighborhood including place attachment (Brown et al. 2003, 2004) neighborhood satisfaction (Oh 2003), length of residency, age of its residents (Oh 2003), and other such factors have been found to increase collective efficacy. Place attachment refers to the emotional bond that develops between residents of a neighborhood due to their physical environment (Brown et al. 2003; Brown and Perkins 1992). Place attachment is often an ever evolving process that changes with the makeup of its residents (e.g., age of its residents), housing and residential changes (e.g., new buildings, introduction of high rises), and economic and/or environmental changes (natural disasters, etc.) (Brown et al. 2003). Despite this, research has found that home owners (Taylor 1996), older residents (Oh 2003), and those involved in community events or agencies (Uchida et al. 2014) have higher place attachment, as well as higher perceived collective efficacy. Those that own their homes, for example, are more likely to stay longer, invest in the upkeep and maintenance of their properties, and may be more likely to bond with their neighborhoods (Uchida et al. 2014). Similarly, older residents are less likely to move and have been known to have stronger attachments to their neighborhoods, often looking after the rest of the residents (Oh 2003; Altergott 1988). In fact, Oh (2003) found in his study of 1123 Chicago residents ages 65 and up that local social bonds, specifically friendship, social cohesion, and trust have significant positive effects on the level of neighborhood satisfaction, and negative effects on the likelihood of mobility. These findings indicate the importance of social interaction and bonding to whether residents are more or less likely to move. As mentioned, frequent mobility or residential turnover is one of the possible factors that can contribute to the decline of a neighborhood. Collective efficacy has and will continue to be part of the discussion when it comes to revitalization efforts of urban neighborhoods as cohesion and trust, the pillars of collective efficacy, have been proved to mediate crime and deviance even in declining neighborhoods (Brown et al. 2004).

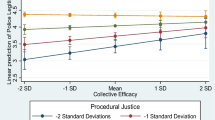

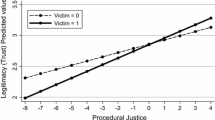

Research on collective efficacy and procedural justice provide insight into why residents trust and cooperate with police. In neighborhoods where police resources are limited and crime is relatively high, obtaining cooperation from residents and enhancing residents’ willingness to exert social control becomes vital to the safety of the community. In order for this to work, residents must perceive police to be legitimate and fair. Legitimacy is measured by whether people trust the police and believe they should obey them (Tyler 1990; Sunshine and Tyler 2003). Perception of police being fair refers to the fairness in the procedures police use to obtain a particular outcome (Thibaut and Walker 1975); therefore, perceiving the police as fair will increase the level of trust citizens have for them (Tyler 2005). Citizens who trust the police are more willing to cooperate by reporting criminal activity and exerting informal social control (Nix et al. 2015). In addition, social cohesion also influences attitudes toward police. Gau et al. (2012) examined social cohesion (trust and closeness with neighbors) and found that residents with high levels of perceived social cohesion had greater perceptions of procedural justice.

Furthermore, the concept of fairness refers to quality of decision-making (objective and neutral), quality of interpersonal treatment (respect and dignity), and citizen involvement in decision-making (Tyler 2005; Nix et al. 2015). The idea is that if residents perceive the police as fair, they are more likely to trust them, perceive them in a positive light, and be more willing to cooperate.

Similarly, in the UK, numerous studies have examined what factors contribute to an individual’s confidence in police officers, and have often found individuals who report a sense of cohesion among their community members also tend to report a higher confidence in police officers (Merry et al. 2011; Perkins 2016). In addition, individuals who were more personally involved in the community felt more confident in police. These findings are consistent with similar research conducted in the USA.

Studies of the effect of gendered attitudes toward the police have found that women are significantly more likely to have positive perceptions of police (Cao et al. 1996), whereas others found little or no differences between gender and attitudes toward police (Ren et al. 2005). Some studies argue that men express a more negative opinion about police and police legitimacy than do women (Hawdon and Ryan 2003; O’Connor 2008). These gender differences in the attitudes toward police can be attributed to differences in the experiences that people have with law enforcement.

A substantial amount of empirical research also examines the relative importance of age and race in measuring residents’ satisfaction with police. Older residents are often more likely to have positive views of police (Gau et al. 2012; Ren et al. 2005). Younger people are more likely to hold a negative perception of police and police services in the area. The studies suggest that younger people’s attitudes are more negative because they are more likely to be involved in formal contact with police, and they are also more likely to be targeted by the law enforcement initiatives and programs (Brunson 2007; Hagan et al. 2005).

When examining race, researchers find that minorities are less trusting in police (Tyler 2005), and have more negative perceptions of police (Engel 2005). Prior research has consistently shown that blacks and Latinos hold lower level of trust and confidence in police and police services than do whites and other racial and ethnic minorities. The increased distrust and dissatisfaction with law enforcement expressed by minority residents are commonly associated with racial profiling, police brutality, and racial impartiality of police (Schuck et al. 2008).

More specifically, a national survey conducted in 2016 found that blacks are approximately two times more likely than whites to report that police are “too quick to use lethal force,” and that police in general are viewed as “too harsh” (Ekins 2016). Furthermore, nearly 40% of black respondents indicated they knew someone who had been abused by police, compared to 18% of white respondents. The survey also found that 65% of all respondents believe that police officers engage in racial profiling. The Baltimore City Survey in 2012 reported that 54% of surveyed Baltimore residents are dissatisfied with police protection and other police services (Schaefer Center for Public Policy 2012).

As mentioned above, the existing research suggests that the level of satisfaction with police services and perception of police–citizen encounters depends on individual and neighborhood factors. While some residents have direct contact with the police, many hold the perception based on real or perceived problems in the neighborhood. It has been found that residents perceiving higher levels of crime in their neighborhood are less satisfied with police services (Decker 1981; Weitzer and Tuch 2005). However, crime rate and perception of crime are not the only important factors to predict the attitudes toward police. The perception of social disorder (graffiti, abandoned houses) has been found to be a predictor of satisfaction with police as well. In addition, more recent research suggests that victimization experiences tend to increase unfavorable attitudes toward police (Homant et al. 1984; Wu et al. 2009).

The goal of this study is to better understand how people from East Baltimore perceive the police–citizen encounters, participate in their community, and the degree to which they are satisfied with police services in their neighborhood. Our study measures the presence of collective efficacy among residents of a high-crime, high-poverty neighborhood in East Baltimore. Based on the findings from previous studies, this study predicts that collective efficacy, the cooperation, social cohesion, and trust among neighbors, leads to willingness to work with law enforcement and perceive them in a positive light. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that residents who trust and interact with each other, and intervene in finding solutions to problems, tend to report positive perceptions of police roles in local initiatives and view police as a critical part of public safety.

Methods

Research setting

From 2013 to 2016, the City of Baltimore received a Byrne Criminal Justice Initiative grant (BCJI) to concentrate research efforts and revitalization strategies in one highly distressed neighborhood in East Baltimore. During the course of the grant period, researchers and community stakeholders participated in data collection and community improvement projects. Two of the key objectives of the BCJI were to improve the level of engagement of residents in neighborhood activities and to reduce criminal activity.

During the first year of the grant in 2013, a plan was developed with community input during meetings and focus groups. Residents and other neighborhood stakeholders provided potential solutions to help reduce crime in the neighborhood. The research team, which consisted of the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance (BNIA) and the School of Criminal Justice (SCJ), both at the University of Baltimore, also provided potential solutions for crime reduction based on prior neighborhood plans and best practices. The community voted on a range of strategies that were then funded during the second and third year of the grant. Fifty percent of the funds were directed to workforce development programs for East Baltimore residents. Twenty-five percent of funding was allocated toward addressing youth programming including recreation, education, and mentoring programs. The final 25% of program funding was designated for cleanliness and environmental improvement of the neighborhood, including greening initiatives, service programs, organizing residents around city services, and other improvements to the neighborhood (see Iyer et al. 2013, 2015, 2016). During the second and third years of the grant, a community survey was conducted.

Data collection

Data used in this study were collected over two different time periods. A neighborhood survey on collective efficacy was administered between June 10 and August 24, 2015. A second round, with a new sample of residents, was administered March 28 through May 2, 2016. To administer the survey in both years, a group of 8–11 residents from the neighborhood were recruited and trained. Members of the survey team administered the survey using a door-to-door, drop-off approach. Survey team members visited each of the randomly selected addresses and sought to administer the survey to the first person who answered the door. Survey team members often circled back to pick up the completed survey the same day of the drop-off, or later during the week. Some team members stayed with participants as they filled out the survey.

The core objective of the survey was to measure the concept collective efficacy—defined as “capacity for residents (and community groups) to exert social control over neighborhood issues, thereby reducing crime. This includes the willingness to work together, trust each other, and intervene in order to achieve that social control” (Sampson 2012). A 64-item survey containing six parts was developed to measure this concept and other variables. Most of the survey items were selected from previous neighborhood research (Cohen-Callow et al. 2014; Sampson 2012; Uchida et al. 2014); however, several items (specifically “Neighborhood participation”) were developed by the researchers and outreach workers in the neighborhood.

Sample

Although surveys were administered during two different time periods, the sample from each survey is unique. The original intent of the survey administration was to identify any changes after the implementation of several interventions in the neighborhood. An effort to re-survey the original sample was a goal; however, researchers were unable to reach the same sample, as only four residents from 2015 also participated in the survey administrated in 2016. Consequently, these four respondents were excluded from the sample. Survey administrators reported several reasons for their inability to reach the original sample such as: the resident moved, passed away, did not answer the door after several attempts, refused the survey, or the home was now vacant. Since the samples from both waves are different, the researchers combined both survey waves into one large sample (N = 191).

Between June 10 and August 24, 2015, a random sample of 336 residential addresses was selected from data obtained from the Maryland Department of Planning. This sample was selected from a total of 1421 occupied residential properties that existed on 69 blocks within the East Baltimore neighborhood. To obtain a representative sample of the neighborhood, we selected five households on each block for a total of 336 addresses.Footnote 1 Prior to the random selection process, vacant properties were identified from the Maryland Department of Planning data and excluded from the random selection process. A total of 79 residents, out of 336 households selected, completed the survey (24% response rate). Twenty-seven percent refused to take the survey (n = 92).Footnote 2

From March 28 through May 2, 2016, a sample of 644 residential addresses was selected from data obtained from the Maryland Department of Planning. This sample was selected from a total of 1374 occupied residential properties on 69 blocks within the East Baltimore neighborhood. In an effort to increase the response rate from year of 2015, ten households on each block for a total of 644 addresses were selected. A total of 112 residents, out of 644 households selected, completed the survey (23% response rate).

Demographics

The majority of participants in the combined sample were female (57%), African-American (75%), and over the age of 46 (39%). Forty-eight percent were employed full-time or part-time and 66% of participant rented their home compared to 34% who owned their home. Fifty-five percent of participants reported planning to stay in the neighborhood for a long time. The average time living in the neighborhood was almost 11 years (Table 1).

Variables

Four dependent variables were constructed to measure the respondents’ attitudes toward police roles, police encounters, and satisfaction with police services. Table 2 displays the survey items and associated coding used to construct these variables. The measures of community policing and police response reflect respondents’ attitudes toward aspects of community policing and expectations for police response. These two variables are additive scales constructed based on two or more items. Table 2 displays the survey items and associated coding used to construct these variables and reliability estimates (e.g., Cronbach’s α). The last two measures, police–citizen encounters and police satisfaction, were constructed based on a single item: (a) respondents’ perception of encounters with the police in the neighborhood and (b) overall satisfaction with the police services in the neighborhood.

The main independent variables are neighborhood trust, community involvement, and community intervening. All three variables are additive scales. The neighborhood trust scale indicates the strength of social cohesion among residents such as willingness to help and to work together to get problems solved, close-knit, trust, friendliness, and satisfaction living in the neighborhood. The community involvement variable is an additive scale measuring the level of social capital among residents of the neighborhood: willingness to help in a time of need, exchanging favors, not hesitating to ask others for help. Response categories for these variables include (a) neither; (b) disagree; and (c) agree. A higher score indicates a higher level of social cohesion among people living in the neighborhood and higher level of social capital. The community intervention scale demonstrates number of interferences of neighbors during problems and disorders that occur in the neighborhood such as: youth skipping school, being disrespectful to an adult, presence of crime such as burglary, drugs, and weapon crimes, and presence of vacant houses. Response categories for community intervention variable include (a) very unlikely; (b) unlikely; (c) likely; and (d) very likely. A higher score indicates a higher number of neighbors’ intervention during problems and disorders in the community.

Control variables include participants’ gender, race, and homeownership. All three control variables are coded as a dummy variable with 1 representing female, black, and homeowner. In addition, age of the respondent is four categories variable indicated age range: (1) younger than 18; (2)18–25; (3) 26–34; (4) 35–45; and (5) 46 and older. Descriptive statistics for all variables in the sample are displayed in Table 3.

Analysis

Two types of multivariate regression analyses, ordinary least squares (OLS) and ordinal logistic regression, were performed in order to examine variation in neighbors’ view toward four attitudinal dimensions. OLS regression was estimated for the models of community policing and police response because the scales are continuous variables. The normality of the error distribution for both models was examined through histograms and probability plots, and the degree of non-normality was low. Plots of residuals and Durbin–Watson statistics were used to verify that the independence of the errors and the independence assumptions were not violated. Ordinal logistic regression was the appropriate method for models examining police encounters and satisfaction with police, as these measures are ordinal variables.

Results

Table 3 summarizes the results from the regression analyses. Community involvement and community intervention are not significant predictors of residents’ attitudes toward the community policing, their expectations for police response, police–citizen encounters, and satisfaction with the police services.

However, attitudes toward community policing, police response, and satisfaction with police are significantly influenced by neighborhood trust. The residents with greater social cohesion have more favorable attitudes toward police response and greater support for community policing and are more likely to report satisfaction with police services in their neighborhood. The neighborhood trust variable on its own showed a moderate explanatory power of attitudes toward community policing, registering a R2 of .194.

In addition to the neighborhood trust variable, expectation for police response is also significantly influenced by the control variables of respondent’ age and homeownership. In line with the literature, residents who rent their homes are less likely to have a positive perception of police response. However, younger respondents tend to view police response more positively. The predictors together account of 17.5% for the variation in attitudes toward police response.

Age is also found to be a consistently significant predictor in predicting variation in attitudes toward police–citizen encounters and respondent’s satisfaction with police services Younger respondents are more likely to report negative encounters with police and are also less likely to be satisfied with the quality of police services in the neighborhood. This result is congruent with the findings from several previous studies that stress the importance of age in shaping citizen’s perception and satisfaction with law enforcement (Weitzer and Tuch 2002).

Race also showed a significant connection with police satisfaction. Black respondents report more satisfaction with the quality of police services in the neighborhood. The variables together (neighborhood trust, age and race) explain about 25% of the variation in police satisfaction.

Contrary to the existing literature, black respondents also report their contact with police mostly positive. The existing literature and research suggest that minorities are more likely than whites to perceive contact with law enforcement negatively, and are also more likely to be dissatisfied with the service of police.

While the extant literature has demonstrated that males evaluate the police more negatively than females, the current study did not show significant relationships between gender and expectations for police responses, attitudes toward police encounters, and satisfaction with police services.

Limitations

Before discussing the direction for future research, two limitations associated with this study should be noted. First, this study used survey data that were collected after an intense month of conflict within the city of Baltimore. In April 2015, a Baltimore resident, Freddie Gray, died while in police custody, which resulted in several weeks of protest and a series of small riots which left significant property damage throughout the city. As a response to the riots, the city went into a state of emergency for a full week. During spring 2016, the second wave of surveying occurred during the criminal trials of six Baltimore City police officers involved in Freddie Gray’s death. The results of the trials yielded one mistrial, one acquittal, and eventually all charges dropped for officers who were waiting to go to trial. Negative perceptions toward law enforcement were intensified during those time frames and may have impacted residents’ responses to the law enforcement survey items. In addition, the low response rate, 24% and 23%, respectively, suggests people’s lack of willingness to respond to surveys. Even with the low response rate, the study does a fairly good job of representing the population from which the survey sample was originally drawn. However, the low response rate also suggests that respondents from high-crime rates areas are perhaps likely to refuse to participate, especially in times of unrest.

Second, police encounter and police satisfaction were measured using a single survey item. Thus, they may not adequately capture the complex connection between police–citizen contact and the complexity of police services. Thus, the findings of this study need to be interpreted with caution. Finally, our models revealed few significant findings and small R2 levels. Thus, future research should consider using additional sources of data to supplement survey information on collective efficacy in Baltimore neighborhoods. For example, in-depth interviews with neighbors might allow researchers to gather useful information regarding factors that may shape the development of collective efficacy, as well as how collective efficacy, or lack of it, influences neighbors and their perception of police and police services.

Discussion

The results from this study have important implications for improving neighborhood cohesion and relations with police. The examination of neighbors’ attitudes toward community policing, police response, citizen–police encounters, and satisfaction with police services generates several main findings. First, neighborhood trust is most evident in residents’ attitudes toward community policing, police response, and the satisfaction with the police services in the neighborhood. Neighborhoods where residents know, help, and trust each other are more likely to agree with community policing approach, have more positive experience with police response, and are overall more satisfied with the police services. The former is in line with the previous research, suggesting that social cohesion is positively related to public satisfaction with police.

This study did not show enough evidence to confirm a link between community involvement, such as helping their neighbors in times of need, and residents’ attitudes toward community policing, police response, police–citizen encounters, and satisfaction with police services. However, a growing body of the literature supports the claim that residents’ perception of police is critical to increase a cooperation between police and citizens. Many argue that a different level of social capital contributes to a different level of satisfaction with police services (McDonald and Stiokes 2006). The measurement of the social capital in this study refers to the connection among people within an immediate social group: the neighbors. Perhaps including measurement of connection to a larger social order (ties across race, class, or religion) might influence the perception of community policing, police response or the satisfaction with the police services.

Enhancing social cohesion and social capital is important for communities who wish to strengthen their relationships among neighbors and with local law enforcement. The East Baltimore neighborhood has a strong group of community organizations and committed long-term residents who meet frequently to discuss local issues. Occasionally, local law enforcement participates in community meetings, although their involvement has been inconsistent over the past few years. Similarly, the consistency of having the same officers involved in community initiatives and patrolling efforts has been problematic for the neighborhood. It is difficult to maintain a relationship with police when officer turnover in the area is high. Building trust and rapport generally takes some time and often takes longer to build between police officers and the community members they serve.

Residents that rent their homes display a high degree of disagreement with police response. Although homeownership did not show any significant effect on attitudes toward community policing, police–citizen encounters and satisfaction with law enforcement, enhancing ways to involve residents who rent their home may be valuable for improving collective efficacy and police relations. Renters are often not as committed to the neighborhood due to the lack of long-term attachment to the area. Creating incentives to involve them in community meetings and neighborhood events might increase their willingness to be involved and might spark interest in remaining in the area. The city has developed homeownership programs such as the “Vacant to Values Program” which provides willing buyers with a financial investment to purchase a formerly vacant or dilapidated home. Economic programs like this one are important, so too are the residents’ perceptions and feelings toward their neighborhood. Therefore, enhancing residents’ interest and commitment to the area may need to occur prior to introducing a homeownership incentive program.

Similarly, it would be beneficial to develop programs that would help engage younger residents in order to improve the overall perceptions of policing within a community, as age was significantly related to police response, police–citizen encounters, and police satisfaction. Such programs would be particularly beneficial, because the younger residents also tend to be the same individuals who are renting homes in a community. In the present study, 76% of homeowners in the sample were older than 45 years.

In terms of race, the findings support past research that shows a connection between individuals’ race and their satisfaction with police services and perception of police–citizen encounters. African-Americans and whites differ significantly in their satisfaction with police; with African-Americans holding less favorable satisfaction and viewing their encounters with police more negatively. The result of this research shows that residents of Baltimore are divided by race in their attitudes toward the police. It seems that the legacy of Baltimore’s racial segregation and very recent disparities in the rates of stops, searches, and arrests of African-Americans have an enduring effect on public satisfaction with police.

The existing literature suggests that residents living in the areas of crime and social disorder are less satisfied with police. However, problems and social disorder in East Baltimore do not significantly affect respondents’ expectation for police responses, attitudes toward community policing and police–citizen encounters, and satisfaction with the police services. This lack of relationship is likely attributed to the fact that residents encounter police for different reasons. The perception of police might vary based on whether the residents initiated encounters to report a crime or disturbance, they became a crime victim, or they were a subject of the encounter. Future studies should include measurements of victimization and other reasons for police–citizen encounters. In order to increase citizen’s satisfaction with police, we need to understand which factors and reasons for the encounter are likely to predict residents’ satisfaction with police. Furthermore, future studies could also examine the concept of mutual trust between police and citizens. Van Craen (2015) states that when police have a higher level of trust in citizens, they are more responsive and cooperative toward citizens. While this study focused exclusively on the perceptions of citizens, it is important to consider the perception of police officers toward the communities they are serving, as their perception may influence the way they interact with community members.

Notes

On blocks with five or less residential properties, we include all properties in the sample.

This includes eight residents who spoke Spanish and were unable to communicate with the survey team.

References

Altergott, K. 1988. Social action and interaction in later life: Aging in the United States. In Daily life in later life: Comparative perspectives, ed. K. Altergott, 117–146. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Bandura, A. 1975. The ethics and social purposes of behavior modification. In Annual review of behavior therapy theory and practice, vol. 3, ed. C.M. Franks and G.T. Wilson. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Brown, B., and D. Perkins. 1992. Disruptions in place attachments. In Place attachment, ed. I. Altman and S. Low, 279–304. New York: Plenum Press.

Brown, G., B.B. Brown, and D.D. Perkins. 2004. New housing as neighborhood revitalization: Place attachment and confidence among residents. Environment and Behavior 36 (6): 749–775.

Brown, B., D.D. Perkins, and G. Brown. 2003. Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: Individual and block level analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology 23: 259–271.

Brunson, R. 2007. “Police don’t like Black people”: African American young men’s accumulated police experiences. Criminology and Public Policy 6: 71–102.

Burgess, E.W. 1925. The growth of the city. In The city, ed. R.E. Park, E.W. Burgess, and R.D. MacKenzie. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Cao, L., J. Frank, and F.T. Cullen. 1996. Race, community context and confidence in the police. American Journal of Police 15 (1): 3–22.

Cohen-Callow, A., K. Hopkins, M. Meyer, and S. Iyer. 2014. Evaluation: Baltimore community foundation target neighborhood initiative. Baltimore, MD: Prepared for the Baltimore Community Foundation.

Decker, S.H. 1981. Citizen attitudes toward the police: A review of past findings and suggestions for future policy. Journal of Police Science and Administration 9: 80–87.

Ekins, E. 2016. Policing in America: Understanding public attitudes toward that police. Cato Institute: Results from a national survey.

Engel, R.S. 2005. Citizens’ perceptions of injustice during traffic stops with police. Journal of Research in Crime & Delinquency 42: 445–481.

Gau, J.M., N. Corsaro, E.A. Stewart, and R.K. Brunson. 2012. Examining macrolevel impacts on procedural justice and police legitimacy. Journal of Criminal Justice 40: 333–343.

Hagan, J., C. Shedd, and M.R. Payne. 2005. Race, ethnicity and youth perceptions of criminal injustice. American Sociological Review 70: 381–407.

Hawdon, J., and J. Ryan. 2003. Police-resident interactions and satisfaction with police: An empirical test of community policing assertions. Criminal Justice Policy Review 14: 55–74.

Homant, R.J., D.B. Kennedy, and R.M. Fleming. 1984. The effect of victimization and the police response on citizens attitudes to the police. Journal of Police Science and Administration 12: 323–332.

Iyer, S., C. Knott, and A. Cantora. 2013. McElderry park: Community plan for crime reduction. Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance, Jacob France Institute, University of Baltimore. http://www.bniajfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/McElderry-Park-BCJI-Plan-Year-1-Final.pdf. Accessed Nov 2018.

Iyer, S., C. Knott, and A. Cantora. 2015. McElderry park: Byrne criminal justice innovation grant. Final report for year 2 funding (2014–2015). Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance, Jacob France Institute, University of Baltimore. http://www.bniajfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/BCJI%20Year%202%20Report%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed Nov 2018.

Iyer, S., C. Knott, and A. Cantora. 2016. McElderry park: Byrne criminal justice innovation grant. Final report for year 3 funding (2015–2016). Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance, Jacob France Institute, University of Baltimore. http://bniajfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/BCJI-Year-3-Report.pdf. Accessed Nov 2018.

Janowitz, M. 1975. Sociological theory and social control. American Journal of Sociology 81: 82–108.

McDonald, J., and R.J. Stiokes. 2006. Race, social capital, and trust in police. Urban Affairs Review 41: 358–375.

Merry, S., N. Power, M. McManus, and L. Alison. 2011. Drivers of public trust and confidence in police in the UK. International Journal of Police Science & Management 14 (2): 118–135.

Nix, J., S.E. Wolfe, J. Rojek, and R.J. Kaminski. 2015. Trust in the police: The influence of procedural justice and perceived collective efficacy. Crime & Delinquency 61 (4): 610–640.

O’Connor, C.D. 2008. Citizen attitudes toward the police in Canada. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 31 (4): 578–595.

Oh, J. 2003. Social bonds and the migration intentions of elderly urban residents: The mediating effect of residential satisfaction. Population Research and Policy Review 22: 127–146.

Perkins, M. 2016. Modelling public confidence of the police: How perceptions of the police differ between neighborhoods in a city. Police Practice and Research 17 (2): 113–125.

Reiss Jr., A.J. 1971. Systematic observations of natural social phenomena. In Sociological methodology, vol. 3, ed. Herbert Costner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ren, L., L. Cao, N. Lovrich, and M. Gaffney. 2005. Linking confidence in the police with the performance of the police: Community policing can make a difference. Journal of Criminal Justice 33: 55–66.

Sampson, R. 2012. Great American city. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, R.J., and S.W. Raudenbush. 1999. Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology 105: 603–651.

Sampson, R.J., S. Raudenbush, and F. Earls. 1997. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277: 918–924.

Schaefer Center for Public Policy. 2012. Baltimore city citizen survey. University of Baltimore. Retrieved from https://finance.baltimorecity.gov/sites/default/files/citizensurvey.pdf. Accessed Nov 2018.

Schuck, A.M., D.P. Rosenbaum, and D.F. Hawkins. 2008. The influence of race/ethnicity, social class, and neighborhood context on residents’ attitudes toward the police. Police Quarterly 11: 496–519.

Shaw, C.R., and H.D. McKay. 1942. Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago. (Reprint ed., 1969).

Sunshine, J., and T.R. Tyler. 2003. The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law & Society Review 37: 513–548.

Taylor, R.B. 1996. Neighborhood responses to disorder and local attachments: The systemic model of attachment, social disorganization, and neighborhood use value. Sociological Forum 11 (1): 41–74.

Thibaut, J., and L. Walker. 1975. Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Thrasher, F.M. 1927. The gang: A study of 1,313 gangs in Chicago. Chicago, IL: Phoenix Books. (Abridged ed., 1963).

Tyler, T.R. 1990. Why people obey the law. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Tyler, T.R. 2005. Policing in Black and White: Ethnic group differences in trust and confidence in the police. Police Quarterly 8: 322–342.

Uchida, C.D., M.L. Swatt, S.E. Solomon, and S. Sean Varano. 2014. Neighborhoods and crime: Collective efficacy and social cohesion in Miami-Dade County. U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/245406.pdf. Accessed Nov 2018.

Van Craen, M. 2015. Understanding police officers’ trust and trustworthy behavior: A work relations framework. European Journal of Criminology 13 (2): 274–294.

Weitzer, R., and S.A. Tuch. 2002. Perceptions of racial profiling: Race, class, and personal experience. Criminology 40: 435–457.

Weitzer, R., and S.A. Tuch. 2005. Determinants of public satisfaction with the police. Police Quarterly 8: 279–297.

Wilson, J.Q., and G. Kelling. 1982. The police and neighborhood safety: Broken windows. The Atlantic Monthly 127: 29–38.

Wu, Y., I.Y. Sun, and R.A. Triplett. 2009. Race, class or neighborhood context: Which matters more in measuring satisfaction with police. Justice Quarterly 26: 125–156.

Zaccaro, S.J., U. Blair, C. Peterson, and M. Zazanis. 1995. Collective efficacy. In Self-efficacy, adaptation, and adjustment, ed. J.E. Maddux, 305–328. New York: Plenum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cantora, A., Wasileski, G., Iyer, S. et al. Examining collective efficacy and perceptions of policing in East Baltimore. Crime Prev Community Saf 21, 136–152 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-019-00065-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-019-00065-7