Abstract

With limited studies on antecedents and consequences of work engagement with special reference to NGOs, two novel antecedents of work engagement, namely workload (job demand) and proactive personality (job resource) are introduced in the study. By drawing on the revised JD-R model, the study empirically examines the indirect effects of job demands, job resources, personal resources, and ideological resources on organizational outcomes, i.e. intention to quit and organizational citizenship behaviour through work engagement in NGOs. The data collected from paid employees of registered NGOs operating in India were analysed using structural equation modelling. The study reveals that workload does not decrease employees' work engagement in NGOs. Whereas employment insecurity was negatively associated with work engagement. Besides, transformational leadership, intrinsic rewards, community service self-efficacy, proactive personality, and public service motivation played a vital role in fostering work engagement in NGOs. Furthermore, work engagement was negatively associated with the intention to quit and positively associated with organizational citizenship behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The rise of non-government organizations (NGOs) has been a vital process in the social and economic development of developing countries such as India (Baviskar, 2001). The success of NGOs significantly depends upon various social actors involved, which include partners, donors, members, volunteers, and employees. NGO employees play a vital role in emancipating the world from the shackles of poverty, illiteracy, violence, child abuse, harassment, etc. However, in contemporary times, NGOs have faced a dynamic environment, complexities from government and state regulations, and globalization (Aboramadan et al., 2020), which have impacted employees’ commitment, performance, and engagement levels. These employees often undergo pressing job demands such as workload, burnout, and employment insecurity (Kostadinov et al., 2021; McEntee et al., 2021), which trigger their turnover (Kostadinov et al., 2021). With employee turnover becoming rampant in NGOs (Habib & Taylor, 1999; Benson, 2012; Kostadinov et al., 2021), it is imperative to address employee-related issues as turnover impacts their success quite intensely.

Work engagement is a gateway to the solution pertaining to employee turnover. It is not only a key indicator of employee retention (Memon et al., 2020) and organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) but also an antidote to burnout (Meynaar et al., 2021). Engaged employees in NGOs can be a significant asset as they are constantly in a positive state of mind wherein they are fully invested, committed to their roles (Vecina et al., 2012), and show a higher tendency to remain associated (Huynh et al., 2014). Drawing from the most common theory to study engagement, job demands and resources theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), we know that individuals with many job resources can cope better with their job demands and show higher levels of engagement (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Besides, every job may have specific job demands and resources depending on the specific job characteristics (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Since NGOs are not-for-profit organizations, their functioning is quite different from for-profit organizations. For instance, employees in NGOs have a different orientation towards their work as their values, strategic goals, and management are strongly aligned with each other (Ridder et al., 2010). They are intrinsically motivated due to their mission (Auriol & Brilon, 2018) and find meaningfulness in their jobs. Since they have a different outlook towards work, the job demands, job resources, and personal resources that lead to their engagement are also different from for-profit organizations as they are also endowed with ideological resources (Selander, 2015).

While the concept of work engagement has been extensively researched in the context of for-profit organizations, research and findings are inadequate in the context of NGOs (Abromadan & Dahleez, 2020; Park et al., 2018). There are studies on the predictors of work engagement in the third sector (Selander, 2015) and NPOs (Akingbola and Berg, 2019; Park, 2018; Aboramadan et al., 2020) but not on NGOs, which are a subset of NPOs (Salamon & Anheier, 1997). NGOs are proactive organizations that are engrossed in serving the nation (De Souza, 2010). Employees in NGOs are passionate about serving the communities; they are more inclined towards non-monetary aspects, such as intrinsic rewards (Borzaga & Tortia, 2006); and exhibit a great deal of transformational leadership (Aboramadan et al., 2020).

Prior studies state that NGOs in India generally function under the leadership and supervision of the main founder who exhibits a “one-man-show” (Shiva and Suar, 2012); is often supported only by a few professionals and even fewer staff employees; and lack in a proper hierarchy (Shiva and Suar, 2012). Since NGOs in India have scarce physical and financial resources (Shiva and Suar, 2012; Mer & Virdi, 2021), they find motivating and engaging their employees challenging. Moreover, NGOs are witnessing increasing job demands such as workload (Ariza-Montes & Lucia-Casademunt, 2016; McEntee et al., 2021) and employment insecurity (Zbuchea et al, 2019; McEntee et al., 2021). In such contexts, it becomes imperative for NGOs to gain clarity on the job demands and resources that might impact their engagement levels. A deep understanding of the antecedents of work engagement is likely to decrease the intention to quit the job, boost organizational citizenship behaviour and performance of the employees and subsequently contribute to the overall effectiveness of the NGOs (Mer & Vijay, 2021).

In this backdrop, this study explores specific job demands, job resources, personal resources, and ideological resources as antecedents of work engagement, their interrelationships, their impact on intention to quit, and organizational citizenship behaviour in NGOs in India. This study contributes to the existing literature in two ways. First, this study takes novel factors such as workload (job demand) and proactive personality (personal resource) as antecedents of work engagement in the NGOs context. Second, it is the first study on NGOs that uses job demands and resources theory to examine the indirect effects of the job demands, job resources, personal resources and ideological resources on two very important organizational outcomes, i.e. intention to quit and organizational citizenship behaviour via work engagement. Thus, the study empirically answers three research questions:

-

1.

What are the antecedents of work engagement with respect to job demands, job resources, personal resources, and ideological resources as relevant in Indian NGOs?

-

2.

What are the consequences of work engagement in Indian NGOs?

-

3.

How does work engagement translate these demands and resources to intention to quit and organizational citizenship behaviour of the employees working in Indian NGOs?

Job Demands-Resources Model: Theoretical Framework of the Study

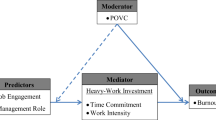

The theoretical foundation of the proposed conceptual model is the job demands-resources (JD-R) model (Fig. 1), given by Bakker and Demerouti (2007). Job demands are the “physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical and/or psychological (i.e. cognitive or emotional) effort or skills and are associated with certain physiological and/or psychological costs”. Role ambiguity, time pressure, workload, employment insecurity, etc., are examples of job demands. Stress results from job demands (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008), leading to employee disengagement.

Source: Bakker and Demerouti (2007)

Revised JD-R model of Work engagement.

On the other hand, job resources refer to “physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are either/or: (i) functional in achieving work goals, (ii) reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, and (iii) stimulate personal growth, learning, and development” (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Job resources help accomplish organizational goals, decrease job demands and increase work engagement (Crawford et al., 2010). Job autonomy, social support, feedback, etc., are examples of job resources. At the same time, personal resources such as resilience, self-efficacy, and self-esteem are the “aspects of the self that are generally linked to resiliency and refer to individuals’ sense of their ability to control and impact upon their environment successfully” (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007).

Background of Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) in India

The rise of concern for social justice, growth for everyone, and empowerment of the marginalized have given an impetus to the growth of civil society, which has encouraged the formation of open and secular institutions such as NGOs that serve as a mediator between the citizens and the state in modern democratic societies (Ghosh, 2009). In India, the government has launched several ambitious programs that involve NGOs in their execution, thus strengthening the role of leadership in NGOs in the success or failure of these programmes. There are more than 1,18,101 different types of NGOs operating in India (Niti Aayog, 2021). They hold a distinctive mediating position in moving inefficient states to efficient markets through services encompassing a wide range of services activities. Indian NGOs are shaped by Indian ethos and have a history of social reform movements that have taken place in India (Sengupta, 2014). The span of their activities is mainly related to religion, spirituality, humanity, environment, etc. While Indian NGOs support the nation’s public services significantly and contribute to mitigating the critical situation of India as a developing country (Ariza-Montes and Lucia-Casademunt 2016), their success largely depends on identified partners, donors, registered members, volunteers, and most importantly employees.

NGOs have a distinct cultural scenario (Sashkin, 1995) of change management, goal achievement, and coordination of efforts, led mainly by the founder's vision (Schneider et al., 1995). Also, NGOs in India face erratic external factors and financial and resource crunch compared to for-profit organizations (Goel & Kumar, 2005). They have to keep functioning under the dynamically-changing external environment that comprises of their donors, stakeholders, government regulations, etc., which often puts challenges on the job demands for the few employees associated with them. For these reasons, NGOs face unique challenges in retaining, motivating, and engaging their employees.

Hypotheses Development

Job Demands as Antecedents of Work Engagement in the Context of Indian NGOs

NGOs are witnessing an increasing magnitude of job demands like workload (Ariza-Montes and Lucia-Casademunt 2016; McEntee et al., 2021) and job insecurity (Baluch, 2017; Zbuchea et al., 2019; McEntee et al., 2021). Humanitarian organizations confront high employee turnover due to job insecurity and workload. The growing magnitude of workload in NGOs has led to high employee turnover (Mer & Virdi, 2021). Studies indicate that a high workload decreases work engagement (Llorens et al., 2007; Taipale et al., 2011; Ahmed et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). Similarly, studies suggest that job insecurity also decreases work engagement (Mauno et al., 2007; Karatepe et al., 2020). However, there has been no attempt to investigate the effect of workload on work engagement in the context of NGOs. The current study analyses the effect of two job demands, namely workload and employment insecurity on work engagement. Based on the above literature, the researchers hypothesize that:

H1

Job demands, specifically the workload, has a significant negative effect on work engagement.

H2

Job demands, specifically employment insecurity, has a significant negative effect on work engagement.

Job Resources as Antecedents of Work Engagement in the Context of Indian NGOs

As per the job demands-resources model, job resources enhance work engagement (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). The study analyses two job resources, namely transformational leadership and intrinsic rewards, as predictors of work engagement in NGOs. Studies indicate that transformational leadership is positively associated with work engagement in non-profit organizations (Freeborough & Patterson, 2016; Aboramadan et al. 2020). In addition to transformational leadership, intrinsic rewards emanate from the job itself (Kim, 2017). Studies indicate that the employees in NGOs are more inclined towards non-monetary aspects and are more committed to work (Borzaga & Tortia, 2006; Aboramadan et al. 2020). Greater learning opportunities are positively associated with work engagement in NPOs (Kim, 2017).

It is interesting to note here that in Indian NGOs, it is generally the main founder who leads and supervises the functioning of the NGO. With a limited number of employees and less salaries due to financial constraints, job autonomy, a vital job resource in NPOs in developed countries, is not visibly seen in Indian NGOs. Most employees in NGOs are made to work in bookkeeping, general administration, raising money, and operations, wherein the extent of autonomy is either limited to setting deadlines or substantially missing. As such, job autonomy is not a salient feature in Indian NGOs, due to which the researchers have selected two salient job resources—transformational leadership and intrinsic rewards. Based on the above literature, the researchers hypothesize that:

H3

Job resources, specifically transformational leadership, positively influence work engagement.

H4

Job resources, specifically intrinsic rewards, positively influence work engagement.

Personal Resources as Antecedents of Work Engagement in the Context of Indian NGOs

The current study analyses two personal resources: proactive personality and community service self-efficacy as predictors of work engagement in NGOs. People who exhibit proactive personalities impact environmental change, take initiative, seek better ways of doing their work, and persevere until they bring about meaningful change. NGOs demand employees who prefer challenging work, struggle for continuous improvement, and search for new opportunities (Rank et al., 2004). Studies indicate that NGOs are very proactive organizations driven by innovative and altruistic people (Souza, 2010). Similarly, community service self-efficacy is “the individual's confidence in his or her own ability to make clinically significant contributions to the community through service" (Reeb et al., 1998). In the face of organizational demands, employees in NGOs with greater community service self-efficacy enjoy greater work engagement (Harp et al., 2017). Based on the above literature, the researchers hypothesize that:

H5

Personal resources, specifically proactive personality, positively influence work engagement.

H6

Personal resources, specifically community service self-efficacy, positively influences work engagement.

Ideological Resources as Antecedents of Work Engagement in the Context of Indian NGOs

According to Selander (2015), ideologically oriented employees with public service motivation join third sector organizations. NGOs are unique organizations and, therefore, cannot be compared with business or government organizations. The factors like value delivery to society, self-motivation, commitment to a cause, voluntary spirit, and strong internal vision make NGOs unique and help in bringing social change (Sridhar & Nagabhushanam, 2008). Based on the above literature, the researchers hypothesize that:

H7

Ideological resource, specifically public service motivation, positively influences work engagement.

Intention to Quit and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour as Consequences of Work Engagement

Intention to quit is a deliberate and willful attempt by employees to leave their organizations, and organizational citizenship behaviour is the behaviour that goes beyond the basic requirements of the job, discretionary to a large extent, and is of benefit to the organization. While work engagement is negatively associated with quitting (Park et al., 2018), it is positively associated with OCB in NGOs (Gupta et al., 2017). Based on the above literature, the researchers hypothesize that:

H8

Work engagement has a significant negative effect on the intention to quit.

H9

Work engagement has a significant positive effect on organizational citizenship behaviour.

Work Engagement as a Mediator Between its Antecedents and Consequences

Kahn (1990) proposed that individual and organizational factors influence work engagement, driving individual attitudes and behaviour such as turnover intention and affective commitment. In other words, work engagement is believed to mediate the relationships between job demands and resources on one hand and job outcomes on the other hand (Schaufeli, 2015).

To study the mediating effect of work engagement between its antecedents like job demands (workload and employment insecurity), job resources (transformational leadership and intrinsic rewards), personal resources (proactive personality and community service self-efficacy), ideological resource (public service motivation) on one hand and intention to quit, on the other hand, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H10

Work engagement mediates the relationship between its antecedents and intention to quit.

To study the mediating effect of work engagement between its antecedents like job demands (workload and employment insecurity), job resources (transformational leadership and intrinsic rewards), personal resources (proactive personality and community service self-efficacy), ideological resource (public service motivation) on one hand and organization citizenship behaviour on the other hand, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H11

Work engagement mediates the relationship between its antecedents and organizational citizenship behaviour.

These hypotheses lead to a conceptual model as presented in Fig. 2.

Method

The study employed a quantitative research design. The data were collected from paid employees of registered NGOs operating in education, livelihood, and environment/disaster relief operations in the Uttarakhand state in India. The total number of registered NGOs in Uttarakhand is 386 (Source: uttarakhand.ngosindia.com). While the researchers considered both national and international NGOs as the samples, the data were collected from only Indian nationals working here. Expatriates or volunteers working in NGOs were not a part of the study.

Participants and Procedure

Total forty-eight NGOs expressed their willingness to be a part of the study. The data were collected through an online link to the questionnaire and through a hard copy of the questionnaire, where there was a lack of access to the internet. Multistage sampling method was used for data collection. Out of 650 employees who took part in the study, 444 employees responded with full details, indicating a response rate of 68%. The participants were selected based on a minimum of 3 years of service or more with the organization. Data collection spanned over eight months. Refer to Table 1 for the respondents' profiles.

Measures

The participants answered all measures on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly agree) to 5 (Strongly disagree).

Work engagement comprising vigour, dedication, and absorption was captured by Schaufeli et al. (2006) nine-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) (Cronbach’s α > 0.80). A sample item is “At my work, I feel bursting with energy”. Workload was measured by two items drawn from Nordic Questionnaire (QPS Nordic) (Cronbach’s α > 0.70). A sample item is “Do you have too much to do”. Employment insecurity was measured using the Job Insecurity Scale (JIS), comprising of four items developed initially by De Witte (2000) (Cronbach’s α > 0.80). A sample item is ‘‘Chances are, I will soon lose my job’’.

Intrinsic reward was captured by four items drawn from Sak’s (2006) rewards and recognition scale (Cronbach’s α > 0.80). A sample item is “My organization gives me learning and development opportunities”. Transformational leadership was captured by seven items (Carless et al., 2000) (Cronbach’s α > 0.80). A sample item is “My supervisor fosters trust, involvement and cooperation among team members”. Community service self-efficacy was gauged with a three-item scale developed by (Reeb et al., 1998) (Cronbach’s α > 0.70). A sample item is “I am confident that, through community service, I can help in promoting social justice”.

Proactive personality was measured with four items from Bateman and Crant (1993) (Cronbach’s α > 0.80). A sample item is “I like to use my know-how to reach good results”.

Public service motivation was measured by a three-item scale developed by (Perry, 1996) (Cronbach’s α > 0.80). A sample item is “I consider my work to be socially beneficial”.

Intention to quit was measured by two items from the validated scale of Colarelli (1984) (Cronbach’s α > 0.70). A sample item is “I frequently think of quitting my job”. Organizational citizenship behaviour was measured with four items from the validated scale of Lee and Allen (2002) (Cronbach’s α > 0.70). A sample item is "I feel that problems faced by my organization are also my problems".

Results

The hypotheses were tested using structural equation modelling. A two-step approach comprising of measurement and structural model was adopted (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Data were analysed using AMOS 22.0. Multicollinearity was checked through the variance inflation factor (VIF). All the items on the questionnaire had VIF values ranging from 1.567 to 2.800. Since the VIF values were less than 5, this ruled out the potential collinearity problem (Hair et al., 2016). To test the measurement model, various fit measures were analysed. The mediating effects were tested by the bootstrap method in AMOS (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). This procedure is done by resampling with replacement, repeated several times. The indirect effect of each subsample is computed. This leads to an overall confidence interval. The reported results are based on bias-corrected and confidence intervals set at 0.95 with 5,000 resamples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Measurement Model

Confirmatory Factor Analysis was used to assess the distinctiveness of various variables. A measurement model was constructed to assess the convergent and discriminant validity. The measurement model comprised ten variables: workload, employment insecurity, transformational leadership, proactive personality, community service self-efficacy, public service motivation, work engagement, intention to quit and OCB. The values of measurement model are: (χ2) = 1551.354, (χ2/df) = 2.114, RMSEA = 0.050, CFI = 0.933 and TLI = 0.925 and thus, the confirmatory factor analysis showed an acceptable overall model fit. Table 2 depicts CR and AVE. Since all the standardized factor loadings are greater than the threshold limit of 0.60 (Barclay et al., 1995) therefore, construct reliabilities are greater than the threshold limit of 0.80 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), and the average variance extracted are greater than the threshold limit of 0.50. Thus, convergent validity is established (Table 2).

Structural Model

The hypotheses were tested using a structural model. The values of measurement model are: (χ2) = 1553.317, (χ2/df) = 2.113, RMSEA = 0.050, CFI = 0.933 and TLI = 0.925. This indicates that the fit indices of the structural model showed a good fit of the data. The results of direct effects are represented in Table 3, and the results of bootstrapped indirect (mediating effects) are shown in Tables 4 and 5. As shown in Table 3, Hypothesis 1 is rejected because workload (job demand) does not negatively affect NGOs’ workforce work engagement (β = 0.015, p > 0.05). On the contrary, Hypothesis 2 is accepted as employment insecurity (job demand) negatively affects work engagement (β = − 0.090, p < 0.05).

The results indicate that job resources are positively associated with work engagement. As hypothesized, intrinsic rewards have a positive effect on work engagement (β = 0.155, p < 0.05), whereas transformational leadership has comparatively a small positive on work engagement effect (β = 0.136, p < 0.05). Thus, hypotheses 3 and 4 are accepted. Similarly, as hypothesized, personal resources are positively associated with work engagement. Proactive personality has a notably robust effect on work engagement (β = 0.387, p < 0.001), whereas community service self-efficacy has comparatively a small positive on work engagement effect (β = 0.113, p < 0.05). Thus, hypotheses 5 and 6 are accepted. The results indicate that ideological resource like public service motivation is positively associated with work engagement (β = 0.227, p < 0.001). Regarding the consequences of work engagement, the results indicate that work engagement strongly affects the employees' intention to quit the job (β = − 0.403, p < 0.01). On the other hand, work engagement exerts a robust positive effect on organizational citizenship behaviour among employees in NGOs (β = 0.372, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypotheses 8 and 9 are accepted.

The results provide partial support for Hypothesis 10. As regards workload, both direct and indirect effects are insignificant. Thus, there is no evidence of mediation of work engagement between workload and intention to quit. On the other hand, there is partial mediation of work engagement between employment insecurity and intention to quit. There is evidence of full mediation of work engagement between transformational leadership, intrinsic rewards, proactive personality, community service self-efficacy, public service motivation on the one hand, and intention to quit on the other hand.

Similarly, hypothesis 11 is partially accepted. There is no evidence of mediation of work engagement between workload and organizational citizenship behaviour. There is partial evidence of work engagement as a mediator between community service self-efficacy, proactive personality on one hand and OCB on the other hand. There is evidence of full mediation of work engagement between employment insecurity, transformational leadership, intrinsic rewards and public service motivation on one hand and OCB on the other hand.

Discussion

The study examines the antecedents and consequences of work engagement in NGOs by drawing on the JD-R model of work engagement. Taking into account the hypotheses related to the antecedents of work engagement in NGOs, the study suggests that job demands may not necessarily decrease work engagement. The study indicated that workload (job demand) in NGOs does not negatively affect the work engagement of its employees. The finding resonates with prior studies (Bormann, 2013; Crawford et al., 2010). A possible explanation could be that employees in NGOs have a different orientation towards work, unlike employees in for-profit organizations, such that they are mission-driven rather than money-driven (Towers Perrin, 2003) and the main “perk” is “working for an NGO” itself (Werker & Ahmed, 2008). On the contrary, some studies found workload to adversely affect work engagement (Llorens et al., 2007; Ahmed, 2017), possibly because workload makes employees stressed at work, thus making them feel a dearth of energy and mental connectivity (Taipale et al., 2011). Interestingly, Mauno et al. (2007) divulged different results, indicating workload to foster employees' work engagement. Thus, there are inconsistent results in the literature, challenging established paradigms regarding workload.

Employment insecurity was reported to have a significant negative relationship with work engagement. Findings reveal employment insecurity as the sixth most crucial antecedent of work engagement in NGOs and also corroborate with the findings of Park et al. (2018). Interestingly, there is an inconsistent finding reported by Selander (2015), wherein employment insecurity is not associated with work engagement. Employment insecurity in NGOs emanates due to the contractual nature of the job (Zbuchea et al., 2019; Baluch, 2017), time-bound projects, the uncertainty of extension of projects by funding agencies, etc.

Findings further suggest that job resources such as transformational leadership and intrinsic rewards are positively associated with work engagement. Transformational leadership is the fourth most crucial antecedent of work engagement in NGOs. The findings corroborate with previous studies (Freeborough & Patterson, 2016; Gözükara & Şimşek, 2015). This is because transformational leaders transfer their zeal to their subordinates through modeling (Breif & Weiss, 2020). It should be noted here that the absence of job autonomy does not bring any difference in the work engagement of the employees in NGOs as transformation leadership plays an important role in inspiring the employees to think creatively and help them to be successful so that they may raise the level of work engagement by bringing in them the needed energy (Terry et al., 2000). Transformational leaders instil values and self-motivation among employees (Shamir et al., 1993), wherein employees work intrinsically without demanding any autonomy in their work. Regarding intrinsic rewards, findings indicate that intrinsic reward is the third most crucial antecedent of work engagement in NGOs. Hulkko-Nyman et al. (2012) and Akingbola & Berz (2019) also divulged similar findings in their study. This is because employees who join the NGOs are mission-driven rather than money-driven (Surtees et al., 2014), work with full dedication and commitment, and are attracted by factors other than monetary compensation (Borzaga & Musella, 2003).

The study further indicates that personal resources such as proactive personality and community service self-efficacy positively relate to work engagement. Proactive personality stands out as a significant antecedent of work engagement in NGOs. The findings corroborate with the findings of Mastenbroek et al. (2017) and Yan et al. (2019). This is because employees in NGOs take personal initiative and persist until and unless they bring a meaningful change in their work (Bakker et al., 2012). Regarding community service self-efficacy, the findings suggest that community service self-efficacy is the fifth most crucial antecedent of work engagement in NGOs. A possible reason could be that when employees are confident that by serving the community, making a positive change in their community, and using their knowledge to resolve “real-life” problems, the employees in NGOs feel engaged in work. The study is in congruence with the study conducted by Harp (2017).

Regarding ideological resources, the result indicates that public service motivation is the second major antecedent of work engagement in NGOs. The main aim of employees in NGOs is to achieve social outcomes, as opposed to making profits (Surtees et al., 2014). Employees in the social service sector are oriented towards serving society (Werker & Ahmed, 2008). The study is congruent with prior studies (Kahn, 1990; Selander, 2015; Park, 2018), which state that employees' perception of their work role induces the investment of physical, cognitive, and emotional energy.

Considering the hypotheses related to the consequences of work engagement in NGOs, the study's findings suggest that work engagement is inversely related to intention to quit. The more the employees are engaged in NGOs, the less is their intention to quit the organization. This suggests that employees engaged in volunteering and altruistic work have less intention to quit the job (Park et al., 2018). Possible reasons for engaged employees' decreased intention to quit are that, first, the passion for serving society propels the individuals to join the NGOs and stay with the organization (Park et al., 2018). Secondly, engaged employees in NGOs brim with a positive state of mind and indulge in serving society in such a manner that they are not touched by the thought of quitting their jobs (Gupta & Shaheen, 2017). Thirdly, since engaged employees are endowed with positive emotions coupled with joy and zeal in their work to serve society (Schaufeli et al., 2006), their tendency to quit their job is low. The result is in congruence with prior studies (de Oliveira & da Silva, 2015; Akingbola & Van den Berz, 2019; Park et al., 2018; Aboramadan et al., 2020).

Taking into account the work engagement as a mediator, the study's findings also indicate that there is no evidence of mediation of work engagement between workload on one hand and intention to quit and OCB on the other hand. Besides, work engagement partially mediates the relationship between employment insecurity and intention to quit and fully mediates the relationship between employment insecurity and OCB. Our findings provide strong evidence of the indirect effect of transformational leadership, intrinsic reward, proactive personality, community service self-efficacy, and public service motivation on intention to quit and OCB through work engagement.

Theoretical and Managerial Implications

This research empirically tests the effect of novel job demand (workload) and personal resource (proactive personality) on work engagement in NGOs. The study's novelty stems from using the JD-R model to empirically examine the indirect effects of job demands, job resources, personal resources, and ideological resources on two significant organizational outcomes, i.e. intention to quit and organizational citizenship behaviour through work engagement in NGOs.

The current study has specific managerial implications for the practitioners, such as founders and leaders of NGOs in India, Bangladesh, and other Southeast Asian countries that have similar work cultures and working conditions of NGOs. NGOs need to know factors fostering and impeding work engagement. Since employment insecurity hinders work engagement, therefore to overcome employment insecurity, the HR Managers can resort to the social enterprise concept in some of their activities for self-sustenance, i.e. apart from the regular free operations of NGOs, they can also run a hospital/school for nominal fees for supporting the mission of the NGO.

Since transformational leadership, intrinsic reward, proactive personality, community service self-efficacy, and public service motivation lead to work engagement, the managers should recruit transformational leaders as supervisors, people with proactive personality, high community service self-efficacy, public service motivation and selfless attitude. This can be ensured by conducting a psychometric test during recruitment and selection. Managers should also provide intrinsic rewards to the employees in NGOs. Corporates that play an essential role in the success of NGOs can help facilitate work engagement by fostering transformational leadership. The corporates can identify people in corporates who exhibit transformational leadership and are an epitome of a just leader. Such leaders can conduct youth leadership programs to foster transformational leadership in NGOs. To boost intrinsic rewards, corporates should provide learning and development opportunities to the employees of NGOs by conducting capacity-building programs and providing peer-to-peer learning platforms at the national level, wherein the employees of various NGOs can come together and learn from each other.

Even government can take initiatives to enhance transformational leadership, intrinsic rewards, community service self-efficacy, and proactive personality in NGOs, which will enhance work engagement. The government can take the initiative to facilitate digital learning in NGOs. Just as SWAYAM is an initiative of the government for promoting e-learning among students and faculty members, similar initiatives can be taken by the government wherein advanced programmes on leadership (with a focus on transformation leadership), community service self-efficacy and proactive personality can be conducted. This will, in turn, enhance work engagement in NGOs.

Conclusion, Limitations and Future Research

Notwithstanding the study's essential implications, it has a few limitations too. First is the research design, which might limit the causality among the selected variables. The current study used a cross-sectional approach, and therefore one cannot confidently claim causal relations based on cross-sectional studies. For this, future research can focus on longitudinal studies. Second, the sample used is employees from Indian NGOs in the northern part of the country, which might limit the generalizability of the study. Although our study is contextualized in Indian NGOs, and our results are consistent with the prior theoretical and empirical literature on the JD-R model, there is a need to replicate the study using a larger sample from other parts of the country, as India is a culturally and geographically diverse country. Similarly, studies can be replicated in other developing or Asian countries whose work culture resonates with Indian culture. Third, our study chooses only selected job resources and personal resources as deemed fit for employees working in Indian NGOs. Future studies can include a host of other job demands and job resources as applicable in the context of NGOs.

The study leaves ample scope for future research. There is a dearth of research on work engagement in NGOs based on Indian cultural values and philosophy. First, ancient Indian wisdom emphasizes nishkam karm (selfless action). Since the NGOs' employees are altruistic and aim to achieve social outcomes instead of making a profit (Surtees et al., 2014), therefore nishkam karm can be another antecedent of work engagement under ideological resources in NGOs. Second, the studies indicate that the employees in NGOs are benevolent, and they join the organization because of the cause served by the organization. Therefore, empirical studies can be conducted by studying the effect of belief in human benevolence (ideological resource) on work engagement in NGOs. Third, studies can also be conducted by adding control variables like gender, age, occupational class, etc., in the proposed model, which has not been explored yet.

References

Aboramadan, M., Albashiti, B., Alharazin, H., & Dahleez, K. A. (2020). Human resources management practices and organizational commitment in higher education: The mediating role of work engagement. International Journal of Educational Management, 34(1), 154–174.

Ahmed, U., Shah, M. H., Siddiqui, B. A., Shah, S. A., Dahri, A. S., & Qureshi, M. A. (2017). Troubling job demands at work: Examining the deleterious impact of workload and emotional demands on work engagement. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(6), 96–106.

Akingbola, K., & van den Berg, H. A. (2019). Antecedents, consequences, and context of employee engagement in non-profit organizations. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 39(1), 46–74.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Ariza-Montes, A., & Lucia-Casademunt, A. M. (2016). Non-profit versus for-profit organizations: A European overview of employees’ work conditions. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(4), 334–351.

Auriol, E., & Brilon, E. (2018). Non-profits in the field: An economic analysis of peer monitoring and sabotage. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 89(1), 157–174.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223.

Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations, 65(10), 1359–1378.

Baluch, A. M. (2017). Employee perceptions of HRM and well-being in non-profit organizations: Unpacking the unintended. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(14), 1912–1937.

Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to casual modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an Illustration.

Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. (1993). The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(2), 103–118.

Baviskar, B. S. (2001). NGOs and civil society in India. Sociological Bulletin, 50(1), 3–15.

Benson, C. (2012). Conservation NGOs in Madang, Papua new Guinea: Understanding community and donor expectations. Society & Natural Resources, 25(1), 71–86.

Bormann S. (2013). Like plants need water - antecedents of work engagement at Sodexo`s. (Doctoral dissertation, Radboud University Nijmegen).

Borzaga, C., & Tortia, E. (2006). Worker motivations, job satisfaction, and loyalty in public and non-profit social services. Non-Profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 35(2), 225–248.

Borzaga, C., & Musella, M. (2003). Produttività ed efficienza nelle organizzazioni nonprofit: il ruolo dei lavoratori e delle relazioni di lavoro. Edizioni31.

Carless, S. A., Wearing, A. J., & Mann, L. (2000). A short measure of transformational leadership. Journal of Business and Psychology, 14(3), 389–405.

Colarelli, S. M. (1984). Methods of communication and mediating processes in realistic job previews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(4), 633.

Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848.

De Souza, R. (2010). NGOs in India’s elite newspapers: A framing analysis. Asian Journal of Communication, 20(4), 477–493.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Freeborough, R., & Patterson, K. (2016). Exploring the effect of transformational leadership on non-profit leader engagement. Servant Leadership: Theory & Practice, 2(1), 49–70.

Ghosh, B. (2009). NGOs, civil society and social reconstruction in contemporary India. Journal of Developing Societies, 25(2), 229–252.

Goel, S. L., & Kumar, R. (2005). Administration and management of NGOs: Text and cases. Deep and Deep publications.

Gupta, M., Shaheen, M., & Reddy, P. K. (2017). Impact of psychological capital on organizational citizenship behavior: Mediation by work engagement. Journal of Management Development, 36(7), 973–983.

Gözükara, I., & Şimşek, O. F. (2015). Linking transformational leadership to work engagement and the mediator effect of job autonomy: A study in a Turkish private non-profit university. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 963–971.

Habib, A., & Taylor, R. (1999). South Africa: anti-apartheid NGOs in transition. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Non-profit Organizations, 10(1), 73–82.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Harp, E. R., Scherer, L. L., & Allen, J. A. (2017). Volunteer engagement and retention: Their relationship to community service self-efficacy. Non-Profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(2), 442–458.

Hulkko-Nyman, K., Sarti, D., Hakonen, A., & Sweins, C. (2012). Total rewards perceptions and work engagement in elder-care organizations: Findings from Finland and Italy. International Studies of Management & Organization, 42(1), 24–49.

Huynh, J. Y., Xanthopoulou, D., & Winefield, A. H. (2014). The job demands-resources model in emergency service volunteers: Examining the mediating roles of exhaustion, work engagement and organizational connectedness. Work & Stress, 28(3), 305–322.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724.

Karatepe, O. M., Rezapouraghdam, H., & Hassannia, R. (2020). Job insecurity, work engagement and their effects on hotel employees’ non-green and nonattendance behaviors. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87, 102472.

Kim, W. (2017). Examining mediation effects of work engagement among job resources, job performance, and turnover intention. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 29(4), 407–425.

Kostadinov, V., Roche, A. M., McEntee, A., Duraisingam, V., Hodge, S., & Chapman, J. (2021). Strengths, challenges, and future directions for the non-government alcohol and other drugs workforce. Journal of Substance Use, 26(3), 261–267.

Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 131–142.

Llorens, S., Schaufeli, W., Bakker, A., & Salanova, M. (2007). Does a positive gain spiral of resources, efficacy beliefs and engagement exist? Computers in Human Behavior, 23(1), 825–841.

Shiva, M. S. A., & Suar, D. (2012). Transformational leadership, organizational culture, organizational effectiveness, and programme outcomes in non-governmental organizations. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Non-profit Organizations, 23(3), 684–710.

Mastenbroek, N. J. (2017). The art of staying engaged: The role of personal resources in the mental well-being of young veterinary professionals. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 44(1), 84–94.

Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., & Ruokolainen, M. (2007). Job demands and resources as antecedents of work engagement: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(1), 149–171.

McEntee, A., Roche, A. M., Kostadinov, V., Hodge, S., & Chapman, J. (2021). Predictors of turnover intention in the non-government alcohol and other drug sector. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 28(2), 181–189.

Memon, M. A., Salleh, R., Mirza, M. Z., Cheah, J. H., Ting, H., Ahmad, M. S., & Tariq, A. (2020). Satisfaction matters: The relationships between HRM practices, work engagement and turnover intention. International Journal of Manpower, 42(1), 21–50.

Mer, A., & Virdi, A. S. (2021). Human resource challenges in NGOs: Need for sustainable HR Practices. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 17(6), 818–837.

Mer, A., & Vijay, P. (2021). Towards enhancing work engagement in the service sector in India: A conceptual model. In Doing business in emerging markets. Routledge, India.

Meynaar, I. A., Ottens, T., Zegers, M., van Mol, M. M., & Van Der Horst, I. C. (2021). Burnout, resilience and work engagement among Dutch intensivists in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis: A nationwide survey. Journal of Critical Care, 62, 1–5.

Niti Aayog (2021). Last accessed on 05–04–2022 and retrieved from https://ngodarpan.gov.in/

Park, S., Kim, J., Park, J., & Lim, D. H. (2018). Work engagement in non-profit organizations: A conceptual model. Human Resource Development Review, 17(1), 5–33.

Perry, J. L. (1996). Measuring public service motivation: An assessment of construct reliability and validity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 6(1), 5–22.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Rank, J., Pace, V. L., & Frese, M. (2004). Three avenues for future research on creativity, innovation, and initiative. Applied Psychology, 53(4), 518–528.

Reeb, R. N., Katsuyama, R. M., Sammon, J. A., & Yoder, D. S. (1998). The community self-efficacy scale: Evidence of reliability, construct validity, and pragmatic utility. Michigan Journal of Community ServiceLearning, 5, 48–57.

Ridder, H. G., & McCandless, A. (2010). Influences on the architecture of human resource management in non-profit organizations: An analytical framework. Non-Profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(1), 124–141.

Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619.

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1997). Defining the non-profit sector: A cross-national analysis (Vol. 3). Manchester University Press.

Sashkin, M. (1995). Organizational culture assessment questionnaire. Ducochon Press.

Schaufeli, W. B. (2015). Engaging leadership in the job demands-resources model. Career Development International, 20(5), 446–463.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 25(3), 293–315.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716.

Schneider, B., Goldstein, H. W., & Smith, D. B. (1995). The ASA framework: An update. Personnel Psychology, 2(1), 81–104.

Selander, K. (2015). Work engagement in the third sector. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Non-profit Organizations, 26(4), 1391–1411.

Sengupta, U. (2014). From seva to cyberspace: The many faces of volunteering in India. Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research, 5(1).

Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1993). The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept-based theory. Organization Science, 4(4), 577–594.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445.

Sridhar, K. M., & Nagabhushanam, M. (2008). NGOs in India-uniqueness and critical success factors, results of an FGD. Vision, 12(2), 15–21.

Surtees, J., Sanders, K., Shipton, H., & Knight, L. (2014). HRM in the not-for-profit sectors. In Human resource management: Strategic and international perspectives. London: Sage Publication.

Taipale, S., Selander, K., Anttila, T., & Nätti, J. (2011). Work engagement in eight European countries: The role of job demands, autonomy, and social support. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 31(7/8), 486–504.

Terry, P. C., Carron, A. V., Pink, M. J., Lane, A. M., Jones, G. J., & Hall, M. P. (2000). Perceptions of group cohesion and mood in sport teams. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4(3), 244–253.

Vecina, M. L., Chacón, F., Sueiro, M., & Barrón, A. (2012). Volunteer engagement: Does engagement predict the degree of satisfaction among new volunteers and the commitment of those who have been active longer? Applied psychology, 61(1), 130–148.

Werker, E., & Ahmed, F. Z. (2008). What do non-governmental organizations do? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 73–92.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121.

Yan, X., Su, J., Wen, Z., & Luo, Z. (2019). The role of work engagement on the relationship between personality and job satisfaction in Chinese nurses. Current Psychology, 38(3), 873–878.

Zbuchea, A., Ivan, L., Petropoulos, S., & Pinzaru, F. (2019). Knowledge sharing in NGOs: The importance of the human dimension. Kybernetes, 49(1), 182–199.

Zhang, M., Zhang, P., Liu, Y., Wang, H., Hu, K., & Du, M. (2021). Influence of perceived stress and workload on work engagement in front-line nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(11–12), 1584–1595.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

It is to specifically state that “No Competing interests are at stake and there is No Conflict of Interest” with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper.

Human and Animal Rights

As a corresponding author along with co-authors of this paper, the paper has been submitted with full responsibility, following due ethical procedure, and there is no duplicate publication, fraud, plagiarism, or concerns about animal or human experimentation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mer, A., Virdi, A.S. & Sengupta, S. Unleashing the Antecedents and Consequences of Work Engagement in NGOs through the Lens of JD-R Model: Empirical Evidence from India. Voluntas 34, 721–733 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00503-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00503-5