Abstract

This chapter presents a review of the literature on the personal and situational work-based identity (WI) antecedents that are to be used in the Bester (A model of work identity in multicultural work settings. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2012) and De Braine (Predictors of work-based identity. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2012) studies.

In the first section this chapter explains how the interactions between the personal and situational characteristics help to develop WI. In the second section the relevance of using the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model as an organising or foundational framework in the prediction of WI is explained despite the lack of specific research evidence that links job resources (JRs) and job demands (JDs) to WI which will be investigated in the current research project.

The third section presents the respective job demands and JRs (that may include ones outside the traditional JD-R model) that are to be used in these two studies and also explains their potential link to WI based on existing literature. No previous research could be found that linked JRs and JDs with WI. In the fourth section the possible mediation role of JDs on the relationship of JRs and WI is briefly explained. No previous research is reported on such relationships in respect of WI.

Finally, this chapter concludes with a discussion of the literature on the biographical and demographical control variables and their possible moderation role in the prediction of WI. Also in this case no specific studies are reported on the moderating effects of such variables in the prediction of WI.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Control variables

- Job demands

- Job Demands-Resources model

- Job resources

- Personal resources

- Push factors

- Pull factors

1 Introduction

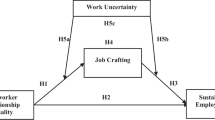

The broad research aims of the Work Identity research project were formulated in relation to the research model (Fig. 1.4) presented in Chap. 1. Chapter 2 provides an explanation of the work-based identity (WI) formation process based on two prominent identity theory streams. The WI construct was conceptualised based on the identity prototypes resulting from the identity formation process. The aim of the current chapter is therefore to present a review of the literature on specific personal and situational antecedents potentially related to WI that are to be used in the Bester (2012) and De Braine (2012) studies.

Firstly, this chapter explains how the interactions between the personal or individual and situational or work characteristics help to develop WI. Thereafter, the relevance of using the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model as a basis or as a foundational framework for the prediction of WI is explained.

What follows next is a series of discussions on personal resources and job demands, and how those selected JRs and JDs are to be used in these two studies. The possible mediation role of JDs on the relationship of JRs and WI is briefly explained.

This chapter then concludes with a discussion of the literature on the potential biographical and demographical control variables and their role in the possible prediction of WI.

2 Interaction of Individual and Work Characteristics

Work identities develop as a result of the interplay between an individual’s dispositions and structural conditions of the work context (Kirpal 2004a). These dispositions could be personality, self-efficacy and the regulatory focus of an individual (Tims and Bakker 2010). It could also include constructs like work beliefs, intrinsic motivation, organisational-based self-esteem and optimism. These constructs or individual dispositions could also be viewed as personal resources. The role that personal resources may have with WI has never been studied before. This is discussed later in this chapter.

These constructs have not been included in any of the doctoral studies in the research project, but it is worth mentioning for future studies on WI. The scope of the two doctoral studies that looked at the antecedents of WI focused mainly on the prediction role of structural conditions. Structural conditions of the work context could, amongst other variables, include work characteristics. Work characteristics were delineated into two broad categories: job demands and JRs, as postulated in the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model in the prediction of work engagement (Xanthopoulou et al. 2007). Consequently, both JDs and JRs are adjusted by employees through the process of job crafting (Tims et al. 2012), which helps employees to modify their work identities (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001).

2.1 Relevance of the JD-R Model in Predicting Work-Based Identity

The JD-R model was developed and introduced by Demerouti et al. in 2001. It has been more extensively used to predict work engagement, well-being and burnout (Hakanen et al. 2005; Mauno et al. 2007; Schaufeli and Bakker 2004) than older stress models such as the Job Demands-Control model (Karasek 1979) and the Effort-Reward Imbalance model (Siegrist 1996). This is due to the limited number of job characteristics that the older models consider (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Van den Broeck et al. 2008), whereas the JD-R model can incorporate all types of both proximal resources or demands (those close to the individual – e.g. supervisor support, etc.) and distal resources or demands (those more removed from the individual – e.g. such as supporting climate). The JD-R model has therefore demonstrated external validity (Xanthopoulou et al. 2007). On these grounds it also becomes highly applicable in the study of WI, as it potentially caters for all professional, occupational and career identities of individuals. The foundational argument is that the ratio between JRs and JDs will either grow (in the case where JRs are proportionally dominant) or inhibit (in the case where JDs are proportionally dominant) WI.

The specific JDs and JRs that were used in this study were primarily taken from the Job Demands-Resource Scale (JDRS) that was developed by Jackson and Rothmann (2005). These resources were growth opportunities, organisational support and advancement. The job demands taken from the JDRS were overload and job insecurity. Additional JRs were also added that were outside of the traditional JDRS model. These included task identity (Hackman and Oldham 1975), team climate (Anderson and West 1998) and perceived external prestige (Carmeli et al. 2006). Work-family conflict (Netemeyer et al. 1996) was an additional job demand outside of the JDRS that was also included as a possible predictor of work identity. Task identity was chosen due to its positive correlation with job involvement (Udo et al. 1997). Job involvement is considered to be an indicator of WI. Team climate was chosen because the use of teams is becoming more prevalent in South African organisations (Robbins et al. 2011). Perceived external prestige was chosen because it influences organisational identification (Smidts et al. 2001), which is regarded as another indicator of WI. The additional job demand work-family conflict was specifically chosen because of the role pressure incompatibility that it can create. This directly influences work identity.

2.2 Job Resources

Job resources (JRs) are ‘…those physical, psychological, social or organisational aspects of a job that either/or (1) reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs; (2) are functional in achieving work goals; and (3) stimulate personal growth, learning and development’ (Demerouti et al. 2001: 501). JRs can further be grouped into proximal and distal JRs. Proximal resources (those closer to the individual) could include resources like skill variety, relationship with supervisors and peers and role clarity. Distal resources (those further removed from the individual) could include team climate, perceived external prestige and flow of information and communication. Furthermore JRs are considered critical for employee retention. When employees experience low work engagement, low job autonomy and low departmental resources, they are more likely to leave their companies or transfer to other departments (De Lange et al. 2008). It is not clear at this point in time whether distal resources show weaker relationships with outcome variables.

JRs are linked to identification through the process of social exchange. A social exchange is judged to be one of quality when employee inputs (examples include work, time and effort) into the relationship are equivalent to the benefits (examples include salary, promotion and recognition) that the employee receives from the relationship. If the social exchange is deemed favourable by the employee, the employee then becomes more motivated to maintain the work relationship (Van Knippenberg et al. 2007). From this point, a merging occurs between the individual and the organisation, and deep structure identification begins to develop (Rousseau 1998). JRs are also related to work-based identity through the process of job crafting. It is postulated that employees may increase their level of JRs in order to handle JDs more successfully (Tims and Bakker 2010). This influences the revision of an individual’s work identity (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001).

2.3 Job Demands

Job demands (JDs) refer to ‘…those physical, social, psychological, or organisational aspects of a job that require sustained physical and/or psychological (i.e. cognitive and emotional) effort on the part of the employee and are therefore associated with certain physiological and/or psychological costs’ (Demerouti et al. 2001: 501). JDs can further be grouped into proximal and distal job demands. Proximal JDs (those closer to the individual) include emotional demands, role ambiguity, role conflict, lack of job control, lack of social support from supervisors and colleagues, lack of feedback and work overload. Distal JDs (those further removed from the individual) could include an unfavourable physical work environment and an unsupportive climate. Job demands are usually associated with the negative characteristics in an individual’s job that, if not adequately dealt with, can lead to ill-health. It is not cleat this point in time whether distal JDs show a weaker relationship with outcome variables.

However, JDs may at times be viewed in a more positive light as job challenges (Van den Broeck et al. 2010). Van den Broeck et al. differentiated between two types of JDs: JDs that hinder optimal functioning, termed job hindrances, and JDs that challenge an employee to exert energy and effort to execute work tasks, termed job challenges. Job hindrances serve to frustrate the process of employees achieving their work-related goals and can lead to ill-health. Job challenges serve to stimulate individual effort to overcome work difficulties and contribute to the fulfilment of individual needs. In as much as job challenges may contribute to as increased well-being, it can also contribute to burnout and ill-health (Van den Broeck et al. 2010). The implication may be that when job challenges become too high to cope with, negative consequences may occur.

Evidence that JDs may be related to work-based identity alludes to the process of job crafting and the process illustrated by Hockey’s (1997) Compensatory Regulatory-Control model, in which employees aim to protect themselves against the pressure from JDs. This is explained later in this chapter. Job crafting is defined as ‘…the physical and cognitive changes individuals make in the task or relational boundaries of their work’ (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001: 179). It is postulated that, as employees engage in crafting their jobs, they may increase their level of job challenges to increase opportunities to use more of their skills, or they may decrease the level of job hindrances to limit the possible negative effects of job hindrances (Tims and Bakker 2010).

3 Dual or Parallel Processes of the JD-R Model

Another motivation for using the JD-R model in the prediction of work-based identity is its ability to view two parallel processes that influence employee well-being. The two parallel processes are: (a) a de-energising process in which JDs exhaust an employee’s mental and physical resources, which could lead to burnout and, eventually, ill-health, and (b) a motivational process in which JRs promote work engagement, which could lead to organisational commitment (Hakanen et al. 2006; Hakanen and Roodt 2010).

The de-energising process associated with the JD-R model is due to the influence of job hindrances. This process can be understood by applying the premise of Hockey’s (1997) Compensatory Regulatory-Control (CRC) model, which states that stressed employees struggle with protecting their primary performance goals (benefits) in the midst of dealing with increased JDs that require an increased amount of mental effort (costs). An employee thus mobilises his or her compensatory effort to cope with this struggle. If this compensatory effort is continuous, the employee will experience energy loss, which could ultimately result in burnout and ill-health. This process is associated with physiological and psychological costs, such as increased sympathetic activity, fatigue and loss of motivation (Hakanen et al. 2006; Hakanen and Roodt 2010). Evidence of this process was found in a cross-lagged longitudinal study done on Finnish dentists in whom JDs were positively correlated with burnout and depression over a period of 3 years (Hakanen et al. 2008).

As part of the motivational process, JRs intrinsically help to foster employee growth, learning and development or extrinsically by helping an employee to achieve his or her work goals (Hakanen et al. 2006; Hakanen and Roodt 2010). The self-determination theory provides support for this motivational process (Deci et al. 1991). The self-determination theory postulates that if the need for competence, relatedness and autonomy (or self-determination) is met in any social context, well-being and increased commitment are enhanced. An example of this can be demonstrated by the proximal JR organisational support, which is shown by supervisory and peer support. JRs play a vital role in promoting work engagement (Bester 2012). Work engagement is closely related to WI. Consequently it has been shown that work engagement and work-based identity shared about 70 % common variance (De Braine and Roodt 2011). WI has also shown to predict work engagement (Bester 2012).

Hobfoll’s (1998, 2002) conservation of resources (COR) theory also provides a sound board for the motivational role that JRs play in employee well-being. The basic premise of this theory is that employees aim to conserve, retain or protect the resources that they have at their disposal in their work environments. They also attempt to bring in additional resources to prevent losing their existing resources, and they will even risk resources to gain resources (gain spiral). Furthermore, employees with many resources are less likely to lose resources, and, vice versa, employees with a lack of resources are more likely to lose resources (loss spiral) (Hobfoll and Shirom 2001). Gaining more resources also enhances engagement (Hakanen and Roodt 2010). Individuals also use their physical, emotional and cognitive selves to perform their roles (Kahn 1990). These are personal resources that assist an individual to work. According to Fredrickson’s (2000) broaden-and-build (BAB) theory, positive emotions help to build enduring personal resources. It helps to foster creativity and the willingness to experiment with new things.

4 Interactions Between Job Demands and Job Resources

Generally, JDs are negatively correlated with JRs (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Xanthopoulou 2007). JRs have been found to be the strongest predictors of work engagement (Bakker et al. 2008; Mauno et al. 2007; Rothmann and Jordaan 2006; Schaufeli and Bakker 2004), especially in the midst of high JDs (Bakker et al. 2008; Rothmann and Jordaan 2006), and have shown to be negatively related to exhaustion and cynicism (Bakker et al. 2004). Furthermore, empirical evidence indicates that JRs are able to buffer the negative impact of JDs on burnout. It was found that JRs buffer the relationship between workload and exhaustion. Social support, for example, buffers the relationship between workload and cynicism (Xanthopoulou et al. 2007). The buffer effect has not been supported in every study on burnout (Bakker et al. 2004). Although the buffer effect of JRs was not addressed as an objective in the current studies of WI, it is mentioned to motivate how important JRs are in employee well-being.

5 Personal Resources

As indicated earlier, the study of the possible relationship that personal resources may have with WI has never been studied before. It is an important construct to study in terms of WI, as personal resources have shown to have positive effects on physical and emotional well-being (Chen et al. 2001; Scheier and Carver 1985). Personal resources are aspects of the self that are generally linked to resiliency and refer to individual’s sense of their ability to control and impact upon their environment successfully (Hobfoll et al. 2003). Personal resources could include self-efficacy, organisational-based self-esteem and optimism. Personal resources were included in the JD-R in the prediction of work engagement (Xanthopoulou et al. 2007). They were found to mediate the relationship between engagement and exhaustion and influenced the perceptions of JDs. Furthermore in a longitudinal study by Xanthopoulou et al. (2009), it was suggested that personal resources were reciprocal with JRs and work engagement. This in essence means that JRs predict work engagement and personal resources, and in turn personal resources predict JRs and work engagement (Demerouti and Bakker 2011). A useful construct that can be used to explain personal resources is PsyCap (abbreviated from Psychological Capital), which consist of the following constructs: hope, efficacy, resilience and optimism (Avey et al. 2010). PsyCap has been shown to positively influence well-being (Avey et al. 2010).

An assumption could be made that it would, based on the positive nature of identification in the workplace and the finding that WI predicts work engagement (Bester 2012), that personal resources as part of the JD-R model could predict WI. Also the development of work identity as a result of the interplay between an individual’s dispositions and structural conditions of the work context is yet to be investigated. This will provide insight into the possible role of personal resources on work identity.

6 Job Resources and the Rationale for Using Some of Them in These Studies

As stated earlier, JRs include those ‘…physical, psychological, social or organisational aspects of a job that either/or (1) reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs; (2) are functional in achieving work goals; and (3) stimulate personal growth, learning and development’ (Demerouti et al. 2001: 501). The JRs that were used in the two doctoral studies on the antecedents of work-based identity were chosen based on the above listed aspects. In this section of the chapter, a specific focus is placed on the following JRs: growth opportunities, organisational support, advancement, task identity, perceived external prestige (organisational reputation), team climate and need for organisational identity (nOID). Growth opportunities will be the first JR discussed.

6.1 Growth Opportunities

The following variables related to growth opportunities within organisations will be discussed: skill variety and opportunities to learn. These indicators of growth opportunities were derived from the adapted JD-Resources Scale (JDRS) (Jackson and Rothmann 2005) that was used in De Braine’s (2012) doctoral study.

6.1.1 Skill Variety

The presence of skill variety has a highly motivational role in the work life of an employee (Nel et al. 2008; Rothmann and Jordaan 2006) and has been shown to be a predictor of job satisfaction (Anderson 1984; Glisson and Durick 1988; Udo et al. 1997). Skill variety refers to ‘…the degree to which a job requires a variety of different activities in carrying out the work, which involves the use of a number of different skills and talents of the employee’ (Hackman and Oldham 1975, p. 161). It also positively relates to an employee’s experienced meaningfulness and responsibility in his or her work (Nel et al. 2008), which helps with the cultivation of work engagement (Olivier and Rothmann 2007). What is important to note is that skill variety has been shown to be positively correlated with job involvement (an indicator of work-based identity) and intention to stay (Udo et al. 1997). Moreover, a job that allows scope for skill variety aids employees in the execution of their daily tasks. This in turn helps employees to fulfil their respective roles and thus strengthening their work identities.

6.1.2 Opportunities to Learn

The growth and development of employees cannot be achieved without providing employees opportunities to learn. Such opportunities assist employees to gain the necessary knowledge, skills and attitudes to fully participate in their respective occupational communities of practice. These communities foster the development of professional identities (Kirpal 2004a; Loogma et al. 2004). Professional identity is regarded as one of the indicators of work identity. This has been regarded as a strategy that employers use to develop and enhance the work identities of their employees (Brown 2004), which can happen through the individual and social learning experiences of employees at work (Collin et al. 2008).

6.2 Organisational Support

Individuals need the support of their organisations to perform in their jobs. An example of organisational support could include managerial and peer support. The perceptions that employees have of the respective support that they get from their organisations can also be regarded as important for the enhancement of work identities. This is known as perceived organisational support. This term was coined and defined by Eisenberger et al. (1986: 501) as the ‘…global beliefs concerning the extent to which the organisation values their contributions and cares about their wellbeing’. If an employee perceives that the organisational support helps to meet their needs for recognition and approval, they will incorporate their organisational membership into their self-identities (Ashforth and Mael 1989). The cognitive schema that is derived from the organisational membership leads to an experienced congruence between their working selves and their broader self-concept (Turner 1978), which enhances their work-based identity.

The following variables related to organisational support within organisations will be discussed: relationship with supervisors and colleagues, communication, role clarity and participation in decision-making. These variables were also taken from the JDRS.

6.2.1 Relationships with Supervisors and Colleagues

Work identities in essence are social identities that individuals display in their specific roles in organisations. Employees take on a role and a relational identity as they interact and work with colleagues, supervisors and clients in their particular work context to achieve their work goals. Research suggests that healthy interpersonal relationships between supervisors and subordinates are critical for the development of organisational identification (Witt et al. 2002) and also help to develop employees’ professional identities (Dobrow and Higgins 2005). Both organisational identification and professional identity are indicators of WI.

Subordinates judge the kind of supervisory support that they receive from their supervisors. Supervisory support refers to ‘…the degree to which employees perceive that supervisors offer employees support, encouragement, and concern’ (Babin and Boles 1996: 60). This creates positive relationships between supervisors and subordinates. Furthermore, positive relationships with supervisors and peers assist with developing teams (Riketta 2005), creating satisfaction (Brunetto and Farr-Wharton 2002; Cohrs et al. 2006) and engaged employees (Bakker et al. 2007; Mostert and Rathbone 2007; Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). It also helps to buffer the effects of JDs on employees (Berry 1998; Xanthopoulou et al. 2007). Interactional justice (perceived fairness of the interpersonal treatment received from the supervisor) is also strongly associated with work-unit identification (Olkkonen and Lipponen 2006).

6.2.2 Flow of Information and Communication

Employee communication has been defined as ‘…the communication transactions between individuals and/or groups at various levels and in different areas of specialisation that are intended to design and redesign organisations, to implement designs and to coordinate day-to-day activities’ (Frank and Brownell 1989: 5–6). Employee communication is an antecedent of organisational identification through two of its components: the content of organisational messages and the communication climate of an organisation. The content of organisational messages includes information about the organisation’s goals and objectives and information regarding the roles that employees perform. Communication climate is described as the communicative elements within a work environment, such as the trustworthiness of information (Smidts et al. 2001). In the study by Smidts et al. communication climate proved to be a better predictor of organisational identification than the content of communication.

6.2.3 Role Clarity

Work roles are regarded as important aspects of the self (Mortimer and Lorence 1989), in which individuals display their WI (Lloyd et al. 2011; Walsh and Gordon 2007). Therefore, the issue of role clarity becomes so important to employees. Role clarity refers to the certainty that individuals have regarding what is expected from them in their work roles (Bush and Busch 1981). If employees lack role clarity, they will struggle to craft their jobs on a task and relational level and struggle to identify with their work. Job crafting is defined as ‘…the physical and cognitive changes individuals make in the task or relational boundaries of their work…’ and which causes work identities to be revised and changed (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001: 179). Furthermore, a lack of role clarity also affects employee affective commitment (Meyer and Allen 1988). It can also lead to employees experiencing mental distance and exhaustion in their work (Koekemoer and Mostert 2006), which will then further cause a de-identification with work.

6.2.4 Participation in Decision-Making

Modern workplaces are allowing employees to engage or participate in decision-making. This has led to the improvement of production methods, the lessening of bureaucracy and the blurring of the boundaries between workers and management. Through this, a decline of traditional class-based identities has occurred (Baugher 2003). Organisations now have to consider how employees participate and exercise their selves in their work (Billet 2006). Active participation in an organisation through an open communication climate helps to develop organisational identification, which, in turn, increases the self-enhancement of employees (Smidts et al. 2001). Self-enhancement is a key motive for identification according to social identity theory (Pratt 1998).

6.3 Advancement

The workplace is considered to be one of the key places where human development and growth occur (Gini 1998). The following variables related to advancement within organisations were taken from the JDRS (Jackson and Rothmann 2005): remuneration, career possibilities and training opportunities. These will be discussed in the next section.

6.3.1 Remuneration

Although it has been shown that individuals connect and identify with organisations based on more than just receiving economic rewards (Dutton et al. 1994), economic rewards are still considered to be one of the primary reasons why people work (Steers and Porter 1991). Pay satisfaction has shown to have a positive impact on job satisfaction (Igalens and Roussel 1999) and intentions to stay (Brown et al. 2004). Furthermore, an argument more closely related to work identity is the notion that a salary helps to enhance an employee’s self-status as they progress to higher career levels. Employees see a connection between a salary increase and the attainment of the next career level (Rowold and Schilling 2006).

6.3.2 Career Possibilities

It is assumed that employees who exhibit high career salience will spend more time exploring career possibilities in organisations. It is also assumed that such employees will also become more involved in their profession’s community of practice, where they can interact with others in their field and further develop their abilities and skills to improve their career or professional identity. This allows for self-status and self-enhancement to occur as the individual’s skill increases (Brown 2004).

6.3.3 Training Opportunities

In a similar way to opportunities to learn, training opportunities can also be utilised as an employer strategy to develop work identities. Such opportunities allow employees to gain job-related competencies (Noe 2005). Furthermore, formal training also plays a motivational role as it helps employees to develop expertise and confidence, to facilitate the process of professional exchange between colleagues, and assists with new options for broader learning (Kirpal 2004b). This encourages employee identification with work (Kirpal 2004b). In a study by Collin (2009), it was found that learning and work-related identity are related to one another.

6.4 Task Identity

Task identity, in a similar way as skill variety, also plays a strong motivational role on both an intrinsic and extrinsic level for employees (Rothmann and Jordaan 2006). It is defined as ‘…the degree to which the job requires completion of a “whole” and identifiable piece of work – that is, doing a job from beginning to end with a visible outcome’ (Hackman and Oldham 1975: 161). Previous studies have shown that task identity is positively correlated with job involvement (an indicator of work-based identity) and intention to stay (Udo et al. 1997). It is also a predictor of job satisfaction (Anderson 1984; Glisson and Durick 1988; Udo et al. 1997). Task identity also influences the experience of meaning at work and sense of responsibility in employees (Nel et al. 2008).

6.5 Perceived External Prestige (PEP)

Perceived external prestige is related to organisational prestige. According Carmeli et al. (2006), there are three key constructs that are presented in research on organisational prestige: corporate reputation, organisational identity and perceived external prestige (PEP). They further stated that each of these constructs can have an influence on employee identification.

Perceived external prestige (PEP) is defined as ‘…the judgment or evaluation about an organisation’s status regarding some kind of evaluative criteria, and refers to the employee’s personal beliefs about how other people outside the organisation such as customers, competitors and suppliers judge its status and prestige’ Carmeli et al. (2006: 93). In a study on corporate image, another term related to PEP by Riordan et al. (1997), it was found that corporate image is positively related to job satisfaction and negatively related to intentions to leave the organisation.

Organisational prestige was found to be a significant antecedent of organisational identification (Mael and Ashforth 1992) and job satisfaction (Tuzun 2007). This may be due to the role that identification with a group plays in enhancing self-image (Ely 1994). Smidts et al. (2001) found that the more prestigious the employee perceives an organisation to be, the greater the potential for identification with the organisation. Similar findings were established by Fuller et al. (2006).

6.6 Team Climate

Team climate represents a team’s shared perception of organisational policies, practices and procedures (Anderson and West 1998). They further propose that it is comprised of four broad factors: (a) shared vision and objectives, (b) participative safety, defined as ‘… a situation in which involvement in decision-making is motivated and occurs in a non-threatening environment’ (Bower et al. 2003: 273), (c) commitment to excellence, involving a shared concern for the quality of task performance and (d) support for innovation, which includes expressed and practical support (West 1990).

According to Klivimaki and Elovainio (1999), team climate also includes perceptions of a shared commitment to teamwork, high standards and systemic support for cooperation. This notion of shared perceptions is supported by Al-Beraidi and Rickards (2003). Individuals need to share their perceptions and work together as a team, and for a healthy team climate to develop, individuals need to interact (Anderson and West 1998). This is supported by Loewen and Loo (2004). The sharing of insights and having a common goal are indicators that individual team members have adopted the group’s perspective as their own (Burke and Stets 2009). This, in turn, helps to create a positive self-identity (Goldberg 2003). Team climate is known to predict process improvement, customer satisfaction and employee satisfaction (Howard et al. 2005).

The following JR, need for organisational identification (nOID), does not form part of the traditional JRs as in the JD-R model list, but was added in an exploratory way by Bester (2012) as a potential resource or pull factor for individuals.

6.7 Need for Organisational Identification

Bester (2012) considered need for organisational identification (nOID) in his study as an antecedent of WI. NOID falls outside the definition of JRs as formulated in the traditional JD-R model. NOID should rather be viewed as a pull factor or a factor that will facilitate WI within the framework of a force field analysis model of WI. NOID is defined as ‘…an individual’s need to maintain a social identity derived from membership in a larger, more general social category of a particular collective’ (Glynn 1998: 240). The larger social category could be an organisation (Kreiner and Ashforth 2004). Individuals are motivated by an organisation’s attributes if it helps to reinforce their individual self-concept (Walsh and Gordon 2007), which thus drives increased performance (Kreitner et al. 1999). Through nOID, a person expresses which role the opposing drives of ‘I or me’ (individual distinctiveness) versus ‘we’ (organisational inclusivity) play in WI (Brewer 1991: 476). Finally, in a study to establish different degrees of identification, Kreiner and Ashforth (2004) found that nOID, organisational identification and positive affectivity are positively associated with one another.

7 Job Demands and the Rationale for Using Some of Them in These Studies

As stated earlier, JDs include ‘…those physical, social, psychological, or organisational aspects of a job that require sustained physical and/or psychological (i.e. cognitive and emotional) effort on the part of the employee and are therefore associated with certain physiological and/or psychological costs’ (Demerouti et al. 2001: 501). JDs may also be categorised as physical, cognitive and emotional demands. The JDs overload and job insecurity form part of the JDRS that was used in this study. The JD work-family conflict was an additional JD that was added in De Braine’s study. The fifth demand (breach of psychological contract) was added in an exploratory fashion in the Bester (2012) study which also falls outside the traditional JD-R model. In this case breach of psychological contract is viewed as a push (restraining) factor in the force field analysis framework. Overload and job insecurity can be regarded as being both cognitive and emotional demands. They both have the potential to trigger cognitive and emotional effort from individuals when required. Work-family conflict can arise as a result of high JDs which can be the result of demands that can be either physical, cognitive and/or emotional. Breach of psychological contract can be regarded as a cognitive and emotional demand. These JDs will be discussed in more detail in the following four sections.

7.1 Overload

Work identities are greatly influenced by workload pressures and competitive work environments (Collin et al. 2008). Work overload, cited as the most frequent job stressor (Oliver and Griffiths 2005), is regarded as anything that places high attentional demands on an employee over an extended period of time (Berry 1998). It is also known as a job strain due to the high demands that is coupled with it (Bakker and Demerouti 2007). Overload can be categorised into quantitative and qualitative overload. Quantitative overload is described as having too much work to do in the time available. This kind of load is known to lead to stress-related ailments such as coronary heart disease. Qualitative overload is characterised by work that is too difficult for an employee (Nel et al. 2008) or work that requires high concentration levels (Dietstel and Schmidt 2009). Two distinctive types of overload are mental overload and emotional overload.

Mental overload influences how an employee delivers his or her work outputs. If employees struggle to perform their daily tasks, it will affect the way they craft their jobs which will, in turn, affect their work identities. On a positive note, cognitive demands have also been shown to be positively related to work engagement (Bakker et al. 2005).

‘Emotions are dependent and activated by social relationships’ (Cartwright and Holmes 2006: 203) and are regarded as being pivotal to how identity is formed and defined (Zembylas 2003). Some jobs and occupations are characterised by a high amount of emotional load or emotional demands, which can negatively influence an employee’s identity. A classic example of this emotional load is particularly prevalent in the work of teachers. Having to continually display a caring attitude can be seen as an emotionally exhausting professional demand (O’Connor 2008). Emotional exhaustion is defined as ‘…the feeling of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by one’s work’ (Maslach and Jackson 1981: 101). It is usually coupled with time pressure and work overload (Lee and Ashforth 1996).

7.2 Job Insecurity

Job insecurity refers to ‘feeling insecure in the current job and level with regard to the future thereof’ (own emphasis) (Rothmann et al. 2006). It forms part of the JDs resources scale (JDRS) (Jackson and Rothmann 2005) and is considered a JD. It is also regarded as ‘…a sense of powerlessness to maintain desired continuity in a threatened job situation’ (Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt 1984: 438). From an employee’s point of view, job insecurity is judged on a cognitive and affective level (Wong et al. 2005). Low job insecurity has a significant, positive effect on the amount of dedication an employee displays in his/her work (Mauno et al. 2007). Bosman et al. (2005) found that individuals who experience job insecurity often experience less work engagement, more exhaustion and work disengagement. Wong et al. (2005) found that job insecurity also has an effect on organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB) and job performance. They further state that these relationships are dependent upon the organisation type and the level of employee trust (Wong et al. 2005), and it has been found to be dependent and varied according to economic sector, gender and the measuring scales used in a particular study (Mauno and Kinnunen 2002). In another study, job insecurity was found to be negatively related to job performance and positively related to absenteeism (Chirumbolo and Areni 2005). In light of the above findings, it is assumed that job insecurity would lessen work identification. It is also noted that organisations that offer job secure work environments are more able to facilitate the development of deep structure identification (Rousseau 1998).

7.3 Work-Family Conflict (WFC)

Work-family conflict has received considerable attention due to the increasing rate of participation by women in the workplace (Chandola et al. 2004), the rise in work-family conflict to the general increase in working hours (Brett and Stroh 2003) and the extension of work hours into family time (Milliken and Dunn-Jensen 2005), and the negative effects of WFC experienced by individuals (Allen et al. 2000). It is usually an outcome of high work demands. In this study we have used it as a predictor of WI because of how closely it is related to the effects of high JDs and the role pressure incompatibility that it can create.

Work-family conflict is also described as work-family interference (WFI) (Greenhaus et al. 2006) and as a job hindrance (Lepine et al. 2005). It is defined as ‘…a form of interrole conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect’ (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985: 77). Greenhaus and Beutell explicate this by stating that work-family conflict exists when ‘(a) time devoted to the requirements of one role makes it difficult to fulfill requirements of another role, (b) strain from participation in one role makes it difficult to fulfill requirements of another; and (c) specific behaviours required by one role make it difficult to fulfill the requirements of another’ (p. 76).

This is supported by Huang (2000). Due to the incompatibility of roles, work-family conflict is also defined as ‘…the extent to which experiences in the work (family) role result in diminished performance in the family (work) role’ (Greenhaus et al. 2006: 65). This definition allows for the cross-role reference in performance to be explained (Greenhaus et al. 2006). There are three forms of work-family conflict: (a) time-based conflict, (b) strain-based conflict and (c) behaviour-based conflict (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985). Time-based conflict is associated with the amount of hours that individuals work and inflexible work schedules. This can lead to strain-based conflict, which usually develops from role conflict and role ambiguity. Behaviour-based conflict arises when behaviour in one role makes fulfilling another role difficult (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985).

Each of the types of work-family conflict relates to role pressure incompatibility (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985). Role pressure incompatibility will negatively affect the role identity of the individual at work, which, in turn, will negatively impact the individual’s WI (Walsh and Gordon 2007).

7.4 Breach of Psychological Contract

Bester (2012) also considered the breach of psychological contract as an antecedent in his study. The psychological contract is a subjective set of expectations (and obligations) that an employee and employer have of each other (Muller-Camen et al. 2008; Robinson and Morrison 2000). An employee’s experience of the psychological contract is influenced by the expectations that the employee has about fairness, employment security, scope of tasks, development, career, involvement and trust (Guest and Conway 1997, 2004). This in turn influences absences, turnover, retention and performance (Muller-Camen et al. 2008). Employees’ perceptions of contract vary depending on the type and contract of breach (Schaupp 2012). On these grounds breach of psychological contract was included as a push factor or demand in this study.

If employees perceive that a breach of psychological contract has occurred between themselves and their organisation, feelings of resentment can develop which can lead to the breakdown of organisational commitment (Geurts et al. 1999) and cause organisational de-identification (Kreiner and Ashforth 2004).

8 Mediation of Job Demands on the Relationship of Job Resources on Work-Based Identity

The JD-R model holds that JRs help to reduce the physiological and psychological costs associated with JDs (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). Furthermore, employees who have high JDs with a lack of resources are likely to develop burnout and experience a reduction in engagement (Hakanen et al. 2006; Hakanen and Roodt 2010). JRs influence JDs. One of the conditions for mediation is that the independent variable (JRs) must significantly account for variation in the presumed mediator (JDs). JRs predict WI (De Braine 2012). It is assumed that the presence of JDs would reduce the relationship that JRs have with WI. This is based on the possible physiological and psychological costs that can be associated with JDs. This provides the basis with which to assess whether JDs mediate the relationship between JRs and work-based identity. The aim was to establish if JDs (mediator) account for the relationship between JRs (predictor) and work-based identity or reduces that relationship. According to Baron and Kenny (1986) if a significant reduction occurs between an independent variable and dependent variable via a mediator, then mediation has occurred. There has been no research conducted on this as yet.

9 Biographical Control Variables in the Prediction of Work-Based Identity

Race, age, nationality and gender are the biographical variables that were explored as possible moderators of the relationship that JDs and JRs had in predicting work-based identity. The theoretical model (the proposed bow-tie model in Fig. 1.4 in Chap. 1) and the concomitant theoretical framework (suggested in Table 1.1 in Chap. 1) guided the researchers in selecting these demographic and biographic variables, since very little empirical evidence exists that links these variables to work-based identity.

9.1 Race

Race is often linked to cultural differences but is usually associated with the physical differences in people (Human 2005). Individuals who are different from the majority race group experience less positive emotional responses to their employing organisations and usually receive lower performance evaluations from their supervisors of a different race (Miliken and Martins 1996). The concept of similarity to others provides insight into this. This concept stems from the similarity-attraction paradigm in which demographic similarity amongst group members leads to interpersonal attraction (Jackson et al. 1991).

Other findings indicate that diversity usually negatively affects groups in the early stages of a group’s development, until individual members become more comfortable with one another and learn how to integrate (O’Reilly et al. 1989). This may imply that race influences identification with an organisation from the initial contact that potential employees have with an organisation. Within the South African work context, race still remains a contentious issue that affects organisational cultures (Motileng et al. 2006). It was found in one study that black, coloured and Indian employees experience higher levels of job insecurity than white employees (Buitendach et al. 2005). There may be several reasons related to this finding in this study, but it is an indicator that race does play a role in the experiences of employees. Furthermore, race is part of an individual’s social identity, according to social categorisation theory (Ashforth and Mael 1989). This means that race can be a social category from which individuals view their in-group (their own race group) in comparison to an out-group (another race group) in an organisation. This can influence social identification within an organisation. As stated earlier, race is also related to cultural differences amongst people; this may also serve as a contributor to differences in work identification. This study will therefore explore if race groups are related to differences in WI levels.

9.2 Gender

Gender is not only a physical characteristic, it is also a socially constructed factor into which girls and boys are socialised into gendered work identities (Buche 2006). The media, educational institutions and role models play a role in this socialisation process. Girls, in particular, may develop a negative, self-fulfilling prophecy that becomes internalised into their work identities, as a result of barriers that have hindered from entering more traditionally male-dominated professions, such as engineering (Buche 2006). According to the gender model, women’s self and professional identity are developed around their interdependent relationships with others and family roles, whereas men are socialised to take on a work identity that is more independent and goal directed (Dick and Metcalfe 2007).

In terms of gender and JDs, it was found that gender influences job insecurity, where males experience higher levels of job insecurity than women (Buitendach et al. 2005). With regard to work-family conflict – another JD – female participants who have high levels of family role salience experience higher work-family conflict than their male colleagues (Biggs and Brough 2005). A study conducted by Mannheim et al. (1997) revealed that the work centrality of women is lower than that of men. This may be attributed to the female identity having strong associations with the family role (Hill et al. 2004).

In the SA context, the younger generations of black women are choosing careers that are more male dominated and are rejecting the more traditional roles of women (Gaganakis 2003). This is contrary to what has occurred in the past and is at least one step in the right direction regarding equal work opportunities. Although these great strides have been made, an argument still exists that gendered work identities require renegotiation and change to cater for the needs of the current world of work (Abrahamson 2006). This change is important as women are experiencing work-family conflict, motherhood issues, insufficient acceptance in the workplace and a paucity of female role models and mentors (Buche 2006). Gender discrimination, for example, still continues, and glass ceilings still exist for women who aspire to top management positions (Grobler et al. 2006). These factors inevitably affect the level of identification that women experience in the workplace. Many women are engaging in what Johnston and Swanson (2007) term cognitive acrobatics to manage their mothering responsibilities and their work identities. In as similar way, this study will explore if gender groups relate to differences in WI score levels.

9.3 Nationality (Cultural Differences)

Bester (2012) considered the moderating role of different nationality groups (national cultures) in his study of the work identities of employees in various multicultural work settings within the UAE. As this study investigates WI in multicultural work settings, the inclusion of nationality is essential to examine this aspect. Within multicultural work settings, sometimes there are many cultural differences amongst individuals within a specific nationality. Hofstede’s (1983) studies on the different cultural dimensions across nations noted that differences influence individual identity, the execution of political power and individual mental programming.

Bester (2012) further noted that national values provide shared meaning in a nation. The thinking patterns and perceptions of different nationalities may therefore be different (Hofstede 1983; Keating and Abramson 2009). This may mean that different nationalities could think about or perceive a WI process in diverse ways as the results of multiple studies into WI-associated concepts have shown. Some researchers proposed that organisational commitment is subordinate to the cultural context (Adler and Graham 1989).

9.4 Age

Each generation has its varying values and needs (Allen 2003, cited in Nel et al. 2008) that influence job satisfaction. Laff (2008) found that all generations in the workplace currently experience dissatisfaction with their current employers, but the younger generation, between the ages of 21–30, is by far the most dissatisfied. Many studies have indicated that older workers experience more job satisfaction that their younger counterparts (Spector 2000). In one study, the psychological contract of older workers was stronger than younger workers (Bal et al. 2008). This may be due to jobs becoming more intrinsically satisfying for individuals in their final career stages, which is shown in most career development models (Berry 1998). In some instances, there are no significant differences between older and younger workers in their job attitudes towards social support, organisational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intentions (Brough et al. 2011). Age is also considered a positive determinant of work engagement (Barkhuizen and Rothmann 2006) and work (role) centrality, which is an indicator of work-based identity (Mannheim et al. 1997).

South Africa has a relatively young population – more than 60 % are younger than 30 years of age (Grobler et al. 2006). According to Martin (2006), employers need to be aware of the characteristics of young workers in the twenty-first century, known as Generation Y. Martin (2006) stated that they are the self-esteem generation who believe that education is ‘cool’. They are multicultural, socially conscious team players who have a sense of immediacy and are requiring the highest ‘maintenance’ in history. It is also noted that, within the South African context, older employees find the growing number of younger workers, women and female managers stressful (Nel et al. 2008), and this has implications for older workers’ WI. Some large companies in France, for example, hire young and highly qualified workers due to the expectation that they will be more flexible in their approach to work and that they would generally display attitudes that are more in tune with the modern workplace (Kirpal 2004a). It is argued that age would have a moderating influence as different generations differ in terms of their needs and values. This would in turn influence what they seek in organisations.

10 Demographical Control Variables in the Prediction of Work-Based Identity

Flowing from the proposed theoretical model and the suggested research framework (in Chap. 1), the following demographic variables have been used as control variables in the doctoral studies: academic qualification, marital status, job level, medical fund and work region. The first moderator under consideration is academic qualification.

10.1 Academic Qualification

Education includes all educational qualifications from elementary level to university degrees (Hankin 2005). It provides individuals with the necessary knowledge, skills (e.g. reading, writing and arithmetic skills), moral values and an understanding of life. Education, in essence, prepares individuals for career success (Nel et al. 2008). It therefore enables individuals to develop a professional identity (Feen-Calligan 2005). In one study, academic qualification was shown to have a small moderating effect on affective and cognitive insecurity (Buitendach et al. 2005).

10.2 Marital Status

Marital status influences internal career orientations (Chompookum and Derr 2004). A career orientation is the occupational self-concept of an individual, which encompasses the individuals ‘…skills, needs, and expectations evolving in the development of a career’ (Van Wyk et al. 2003: 62). This is then directly linked to the career identities (an indicator of WI) of individuals. Internal career orientations vary from individual to individual. It is the product of individuals’ motives, values, talents and personal constraints (Chompookum and Derr 2004). Personal constraints are those things that may constrain an individual pursuing certain career decisions solely on the basis of their values, motives and talents. An example of this would be a mother who has children and is given an opportunity to develop her career by studying abroad and decides not to embark on this opportunity due to her spousal and mothering responsibilities.

Furthermore, it has been reported that married employees with children have a ‘getting secure’ internal career orientation (characterised by a need for lifetime employment and job security), while single employees tend to have ‘getting high’ (characterised by exciting work and entrepreneurial opportunities) and ‘getting free’ career orientation (characterised by seeking positions with greater autonomy and personal space) (Chompookum and Derr 2004; Derr 1986, 1987). It was found that husband-wife relationships moderate the relationship between experienced stress and well-being (Burke and Weir 1977). So marital status may influence work identity through an individual’s internal career orientations.

10.3 Job Level

Another term for job level is job grade. Job grades are used to sort jobs into categories based on their value within an organisation. Through the process of job evaluation, which is ‘…a systematic comparison done in order to determine the worth of one job relative to another…’, job grades are created for pay purposes (Dessler 2008: 433). Each job grade contains jobs that are similar in terms of requirements, duties and responsibilities (Dessler 2008). Job grades are also associated with certain roles, so it is assumed that job grades are related to an employee’s role identity. It is therefore argued that job level will have a moderating influence on the relationship that work-based identity has with JDs and JRs.

10.4 Medical Fund

Individuals that have permanent work contracts usually receive the benefit of having a medical aid or fund with the organisation. Many organisations usually contribute towards a portion of their employees’ medical fund. This is a benefit that is regarded as very important to employees due to the high cost of medical treatment. This may encourage or enhance organisational identification, as employees may feel greatly supported by their organisation. Although there was no literature that provided evidence that membership of a medical fund moderates the relationship that work-based identity may have with JDs and JRs, it is assumed that it will have an influence, due to the increase in employees experiencing burnout and occupational stress. Employees that experience stress-related illnesses are more likely to make use of their medical funds membership.

10.5 Work Location (Work Region)

Large organisations usually operate within different geographical regions or provinces of a country. Organisations differ in how they set up or organise their operations across a given geographical space – resulting in organisational regions. Within these different regions, the organisation has various interrelationships with its consumers, competitors, suppliers, intermediaries and the labour market. These regions are often referred to as an organisation’s market or task environment (Banhegyi et al. 2008). Each region has its own sociocultural environment that influences the way the business operates (Banhegyi et al. 2008). Furthermore, employees may be more attracted to work in certain regions that have certain facilities such as universities, schools and shopping malls than regions where this is lacking. Sometimes large organisations base some of their functions within certain regions, for example, one region may be responsible for manufacturing or production, and another region may be responsible for its head office activities. This then ultimately influences the functions and responsibilities of employees in a particular region. In turn, such decisions have an impact on what development and growth opportunities are available to individuals and may therefore influence the activation or development of their work identities.

11 Conclusions and Implications for Research

A systematic review of the literature on the potential antecedents of WI highlighted the following key points:

-

1.

WI is a relatively ‘new’ construct in the literature that has been explored more qualitatively, than quantitatively. The lack of quantitative empirical research that specifically links potential antecedents to WI is evident from this review.

-

2.

The traditional JD-R Model as used in the JDRS has shown potential to be a highly applicable as a predictive or baseline model for explaining WI due to its ability to be used across a variety of jobs and its consideration of situational characteristics of work (i.e. JDs and JRs) that are important for WI formation and ultimately well-being. It should however also be kept in mind that the JD-R model was not initially designed to predict WI.

-

3.

Based on sound theorisation it was argued why these selected JRs and JDs in this study are (or could be) related to WI. These selected JRs and JDs do not all fall within the traditional JD-R model, and some were selected based on pure pragmatic grounds or evidence from practice.

-

4.

However, the literature is sparse on these relationships. Only in some instances is it reported that certain JDs and JRs have a relationship with WI facets, for example, perceived external prestige has a strong relationship with organisational identification. No specific studies could be found that related such antecedents to the complete WI construct.

-

5.

No empirical evidence is reported in the literature that indicates that JRs mediate the relationship between JDs and WI. The current study’s assumption of a relationship was based on the premise of the JD-R Model where JRs serve as buffers that help to reduce the physiological and psychological costs associated with JDs (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004).

-

6.

The rather restrictive nature of the traditional JD-R model is also acknowledged, because it does not incorporate all possible push and pull factors that relate to WI. Other push and pull factors outside the traditional JD-R model were included in this study.

-

7.

Many of the biographical and demographic variables show relationships with the facets of WI, such as age with work (role) centrality, but no evidence is reported on such relationships with the WI construct.

-

8.

The role that personal resources could play in the prediction of WI was also considered in this review. These personal resources’ impact has yet to be explored and established in research. Based on their proximity to the individual, it is argued that they may potentially serve as mediators with a wide range of other more distal variables.

References

Abrahamson, L. (2006). Exploring construction of gendered identities at work. In S. Billet, T. Fenwick, & M. Somerville (Eds.), Work, subjectivity & learning (pp. 105–121). Dordrecht: Springer.

Adler, N., & Graham, J. (1989). Cross-cultural interaction: The international comparison fallacy? Journal of International Business Studies, 20(3), 515–537. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490367.

Al-Beraidi, A., & Rickards, T. (2003). Creative team climate in an international accounting office: An exploratory study in Saudi Arabia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 18(1/2), 7–18. doi:10.1108/02686900310454156.

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E. L., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 278–308.

Anderson, C. H. (1984). Job design: Employee satisfaction and performance in retail stores. Journal of Small Business Management, 22, 9–17.

Anderson, N. R., & West, M. A. (1998). Measuring climate for work group innovation: Development and validation of the team climate inventory. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 19(3), 235–258.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organisation. The Academy of Management Review, 14, 20–39.

Avey, J. B., Luthans, F. L., Smith, R. M., & Palmer, N. F. (2010). Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(1), 17–28. doi:10.1037/a0016998.

Babin, B. J., & Boles, J. S. (1996). The effects of perceived co-worker involvement satisfaction. Journal of Retailing, 72(1), 57–75. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(96)90005-6.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309–328. doi:10.1108/02683940710733115.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43(1), 83–104. doi:10.1002/hrm.20004.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. (2005). The crossover of burnout and work engagement among working couples. Human Relations, 58, 661–689. doi:10.1177/0018726705055967.

Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 274–284. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.274.

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work and Stress, 22(3), 187–200. doi:10.1080/02678370802393649.

Bal, P. M., De Lange, A. H., Jansen, P. G. W., & Van Der Velde, M. E. G. (2008). Psychological contract breach and job attitudes: A meta-analysis of age as a moderator. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72, 143–158.

Banhegyi, S., Bates, B., Booysen, K., Bosch, A., Botha, M., Cunningham, P., & Southey, L. (2008). Business management. Fresh perspectives. Cape Town: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Barkhuizen, N., & Rothmann, S. (2006). Work engagement of academic staff in South African higher education institutions. Management Dynamics, 15(1), 38–46.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychology research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Baugher, J. E. (2003). Caught in the middle? Worker identity under new participatory roles. Sociological Forum, 18(3), 417–439. doi:10.1023/A:1025717619065.

Berry, L. M. (1998). Psychology at work: An introduction to industrial and organisational psychology (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bester, F. (2012). A model of work identity in multicultural work settings. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg.

Biggs, A., & Brough, P. (2005). Investigating the moderating influences of gender upon role salience and work-family conflict. Equal Opportunities International, 24(2), 30–41. doi:10.1108/02610150510787999.

Billet, S. (2006). Work, change and workers. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/1-4020-4651-0.

Bosman, J., Rothmann, S., & Buitendach, J. H. (2005). Job insecurity, burnout and work engagement: The impact of positive and negative affectivity. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31(4), 48–56.

Bower, P., Campbell, S., Bojke, C., & Sibbald, B. (2003). Team structure, team climate and the quality of care in primary care: An observational study. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 12, 273–279. doi:10.1136/qhc.12.4.273.

Brett, J., & Stroh, L. K. (2003). Working 61 hours per week: Why do managers do it? Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 67–68. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.67.

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 475–482. doi:10.1177/0146167291175001.

Brough, P., Johnson, G., Drummond, S., Pennis, S., & Timms, C. (2011). Comparisons of cognitive ability and job attitudes of older and younger workers. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 30(2), 105–126.

Brown, A. (2004). Engineering identities. Career Development International, 9(3), 245–273. doi:10.1108/13620430410535841.

Brown, W., Yoshiaka, C., & Munoz, P. (2004). Organisational mission as a core dimension in employee retention. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration, 22(3), 28–43.

Brunetto, Y., & Farr-Wharton, R. (2002). Using social identity theory to explain the job satisfaction of public sector employees. The International Journal of Public Sector Management, 15(7), 534–551. doi:10.1108/09513550210448571.

Buche, M. W. (2006). Gender and IT professional work identity. In E. Trauth (Ed.), Gender and IT encyclopaedia (pp. 434–439). University Park: Information Science Publishing. doi:10.4018/978-1-59140-815-4.ch068.

Buitendach, J. H., Rothmann, S., & De Witte, H. (2005). The psychometric properties of the job insecurity questionnaire. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31(4), 7–16.

Burke, P. J., & Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity theory and social identity theory. Retrieved from http://www.scribd.com/doc/19720726/identity-theory-and-social-identity-theory

Burke, R. J., & Weir, T. (1977). Marital helping relationships: The moderators between stress and well-being. The Journal of Psychology, 95, 121–130. doi:10.1080/00223980.1977.9915868.

Bush, R. F., & Busch, P. (1981). The relationship of tenure and age to role clarity and its consequences in the industrial sales force. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 2(1), 17–23.

Carmeli, A., Gilat, G., & Weisberg, J. (2006). Perceived external prestige, organisational identification and affective commitment: A stakeholder approach. Corporate Reputation Review, 9(2), 92–104.

Cartwright, S., & Holmes, N. (2006). The meaning of work: The challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Human Resource Management Review, 16, 199–208.

Chandola, T., Martikainen, P., Bartley, M., Lahelma, E., Marmot, M., Michikazu, S., & Kagamimori, S. (2004). Does conflict between home and work explain the effect of multiple roles on mental health? A comparative study of Finland, Japan and the UK. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(4), 884–893.

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organisational Research Methods, 4, 62–83.

Chirumbolo, A., & Areni, A. (2005). The influence of job insecurity on job performance and absenteeism: The moderating effect of work attitudes. Journal of Individual Psychology, 31, 65–71.

Chompookum, D., & Derr, C. B. (2004). The effects of internal career orientations on organisational citizenship behavior in Thailand. Career Development International, 9(4), 406–423. doi:10.1108/13620430410544355.

Cohrs, J. C., Abele, A. E., & Dette, D. E. (2006). Integrating situational and dispositional determinants of job satisfaction: Findings from three samples of professionals. The Journal of Psychology, 140(4), 363–395.

Collin, K. (2009). Work-related identity in individual and social learning at work. Journal of Workplace Learning, 21(1), 23–35.

Collin, K., Paloniemi, S., Virtanen, A., & Etelopelto, A. (2008). Constraints and challenges on learning and construction of identities at work. Vocations and Learning, 1, 191–210. doi:10.1007/512186-008-9011-4.

De Braine, R. (2012). Predictors of work-based identity. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg.

De Braine, R., & Roodt, G. (2011). The job demands- resources model as predictor of work identity and work engagement: A comparative analysis. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(2), Art. #889, 11 pages. doi:10.4102/sajip.v37i2.889.

De Lange, A. H., De Witte, H., & Notelaers, G. (2008). Should I stay or should I go? Examining longitudinal relations among job resources and work engagement for stayers versus movers. Work and Stress, 22(3), 201–223. doi:10.1080/02678370802390132.

Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychology, 26, 325–355. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2603&4_6.

Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37, 1–9. doi:10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499.

Derr, C. B. (1986). Managing the new careerists: The diverse career success orientations of today’s workers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Derr, C. B. (1987). What value is your management style? Personnel Journal, 66(6), 75–83.

Dessler, G. (2008). Human resource management (11th ed.). Cranbury: Pearson Education Inc.

Dick, G., & Metcalfe, B. (2007). The progress of female police officers: An empirical analysis of organisational commitment and tenure explanations in two UK police forces. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 20(2), 81–100. doi:10.1108/09513550710731463.

Dietstel, S., & Schmidt, K. (2009). Mediator and moderator effects of demands on self-control in the relationship between work load and indicators of job strain. Work and Stress, 23(1), 60–79. doi:10.1080/02678370902846686.

Dobrow, S. R., & Higgins, M. C. (2005). Developmental networks and professional identity: A longitudinal study. Career Development International, 10(6), 567–583. doi:10.1108/13620430510620629.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organisational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 239–263. doi:10.2307/2393235.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchinson, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organisational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500.

Ely, R. J. (1994). The effects of organisational demographics and social identity on relationships among professional women. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 203–238. doi:10.2307/2393234.

Feen-Calligan, H. (2005). Constructing professional identity in art therapy through service-learning and practica. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 22(3), 122–131.

Frank, A., & Brownell, J. (1989). Organisational communication and behaviour: Communicating to improve performance. Orlando: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Fredrickson, B. (2000). Why positive emotions matter in organisations. Lessons from the broaden-and-build model. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 4, 131–142.

Fuller, J. B., Hester, K., Barnett, T., Frey, L., & Relyea, C. (2006). Perceived organizational support and perceived external prestige: Predicting organizational attachment for university faculty, staff, and administrators. The Journal of Social Psychology, 146(3), 327–347. doi:10.3200/SOCP.146.3.327-347. PMid: 16783985.

Gaganakis, M. (2003). Gender and future role choice: a study of black adolescent girls. South African Journal of Education, 23(4), 281–286.

Geurts, S. A., Schaufeli, W. B., & Rutte, C. G. (1999). Absenteeism, turnover intention and inequity in the employment relationship. Work and Stress, 13, 253–267. doi:10.1080/026783799296057.

Gini, A. (1998). Work, identity and self: How we are formed by the work we do. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(17), 707–714. doi:10.1023/A:1017967009252.

Glisson, C., & Durick, M. (1988). Predictors of job satisfaction and organisational commitment in human service organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 61–81. doi:10.2307/2392855.

Glynn, M. (1998). Individual’s need for organisational identification (nOID): Speculations on individual differences in the propensity to identify. In D. Whetten & P. Godfrey (Eds.), Identity in organisations: Building theory through conversations (pp. 238–244). Thousand Oakes: Sage.

Goldberg, C. B. (2003). Applicant reactions to the employment interview. A look at demographic similarity and social identity theory. Journal of Business Research, 56, 561–571. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00267-3.

Greenhalgh, L., & Rosenblatt, Z. (1984). Job insecurity: Towards conceptual clarity. Academy of Management Review, 9, 438–448.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

Greenhaus, J. H., Allen, T. D., & Spector, P. E. (2006). Health consequences of work-family conflict: The dark side of the work-family interface. Employee health, coping and methodologies. Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being, 5, 61–98. doi:10.1016/S1479-3555(05)05002-X.

Grobler, P., Warnich, S., Carrell, M. R., Elbert, N. F., & Hatfield, R. D. (2006). Human resource management in South Africa (3rd ed.). London: Thomson Learning.

Guest, D., & Conway, N. (1997). Employee motivation and the psychological contract. London: CIPD.

Guest, D., & Conway, N. (2004). Employee well-being and the psychological contract. London: CIPD.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 159–170. doi:10.1037/h0076546.

Hakanen, J. J., & Roodt, G. (2010). Using the job demands-resources model to predict engagement: Analysing a conceptual model. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement, a handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 85–101). Hove: Psychology Press.

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2005). How dentists cope with the job demands and stay engaged: The moderating role of job resources. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 113, 487–497. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00250.xPMid:16324137.

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 495–513. doi:10.1016/j. jsp.2005.11.001.

Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The Job Demands-Resources model: A three year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment and work engagement. Work and Stress, 22(3), 224–241. doi:10.1080/02678370802379432.

Hankin, H. (2005). The new workforce. New York: Amacom.

Hill, E. J., Yang, C., Hawkins, A. J., & Ferris, M. (2004). A cross-cultural test of the work-family interface in 48 countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1300–1316. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00094.x.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1998). Stress, culture and community: The psychology and philosophy of stress. New York: Plenum Press.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6, 307–324. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307.

Hobfoll, S. E., & Shirom, A. (2001). Conservation of resources theory. In R. Golembiewski (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behaviour (pp. 57–80). New York: Dekker.