Abstract

The Corporation for National and Community Service defines professional skills-based community service as “the practice of using work-related knowledge and expertise in a volunteer opportunity.” Traditional definitions of volunteer work in organizational communication scholarship, however, are typically based on (1) the bifurcation between work and volunteer activity; (2) low barriers to volunteer entry and exit; (3) the lack of managerial power/control over volunteers; and (4) the altruistic focus of volunteer work. An analysis of interviews with 19 skills-based volunteers highlights the identity and role tensions inherent in professional volunteering and serves as the basis for a proposal for a new way to visualize volunteering characterized by spectrums of tension rather than by the traditional lens of “not work.”

Résumé

La Corporation for National and Community Service (corporation pour les services nationaux et communautaires) définit les services communautaires professionnels offerts sur la base des compétences comme « la pratique consistant à utiliser des connaissances et de l’expertise professionnelles à des fins bénévoles ». Cependant, les définitions traditionnelles du travail bénévole que l’on retrouve dans les documents académiques sur les communications organisationnelles se basent typiquement sur (1) la bifurcation entre les activités professionnelles et bénévoles ; (2) les faibles obstacles à l’entrée et à la sortie des bénévoles ; (3) le manque de contrôle/d’encadrement des bénévoles ; et (4) l’aspect altruiste du travail bénévole. Une analyse d’entrevues menées auprès de 19 bénévoles offrant des services sur la base de leurs compétences lève le voile sur les tensions entre identités et rôles inhérentes au bénévolat professionnel, et sert de fondement pour proposer un nouveau mode de visualisation de celui-ci en le caractérisant par des spectres de tensions plutôt qu’à travers le prisme traditionnel du « non-travail ».

Zusammenfassung

Die Corporation for National and Community Service definiert professionelle und qualifizierte Gemeindedienstleistungen als „die Praxis, arbeitsbezogene Kenntnisse und Expertise in einer ehrenamtlichen Tätigkeit anzuwenden“. Die traditionellen Definitionen von ehrenamtlicher Arbeit im Wissenschaftsbereich Organisationskommunikation beruhen jedoch typischerweise auf (1) der Teilung von Arbeit und ehrenamtlicher Tätigkeit, (2) den niedrigen Barrieren für die Aufnahme und Beendigung einer ehrenamtlichen Tätigkeit, (3) der nicht vorhandenen Führung oder Kontrolle gegenüber anderen Ehrenamtlichen und (4) dem altruistischen Fokus der ehrenamtlichen Arbeit. Eine Analyse von Interviews mit 19 fachlich qualifizierten Ehrenamtlichen stellt die Identitäts- und Rollenkonflikte heraus, die mit einer professionellen ehrenamtlichen Tätigkeit einhergehen, und dient als Basis für einen Vorschlag, die ehrenamtliche Arbeit als eine von Spannungen gekennzeichnete Tätigkeit neu zu visualisieren statt durch die traditionelle Perspektive der „Nicht-Arbeit“ zu betrachten.

Resumen

La Corporación para el Servicio Nacional y Comunitario define el servicio a la comunidad profesional basado en competencias como “la práctica de usar el conocimiento y la pericia relacionados con el trabajo en una oportunidad como voluntario.” Las definiciones tradicionales del trabajo voluntario en los estudios académicos sobre comunicación organizativa, sin embargo, se basan normalmente en (1) la bifurcación entre el trabajo y la actividad de voluntario; (2) barreras bajas para la entrada y salida de voluntarios; (3) la falta de poder/control de la gestión sobre los voluntarios; y (4) el enfoque altruista del trabajo del voluntario. Un análisis de entrevistas de 19 voluntarios basados en las competencias resalta la identidad y las tensiones de rol inherentes al voluntariado profesional y sirve de base para una propuesta para una nueva forma de visualizar el voluntariado caracterizada por espectros de tensión en lugar de por la lente tradicional de “no trabajo”.

Chinese

国家和社区服务公司将基于职业技能的社区服务定义为“在志愿机会中使用工作相关的知识和专业知识的实践”。传统的志愿定义适合组织沟通学术研究;然而,通常基于 (1) 工作和志愿活动之间的分歧;(2) 较低的志愿进入和退出障碍;(3) 缺少志愿的管理能力/控制;和 (4) 志愿工作的无私重点。对19位基于技能的志愿者采访的分析突出了职业志愿内在的身份和角色压力,作为新的可视化使用压力范围而不是传统“不运行”视角特性化的建议书的基础。

Arabic

المؤسسة للخدمة الوطنية والمجتمع توضح المهارات المهنية على أساس خدمة المجتمع القائم على إنها “ممارسة إستخدام عمل ذوصلة بالمعرفة والخبرات في فرصة التطوع”. التوضيح التقليدي للعمل التطوعي في منحة التواصل التنظيمية، مع ذلك، عادة ما تكون على أساس(1) التشعب بين العمل والنشاط التطوعي؛ (2)إنخفاض حواجز لدخول التطوع و الخروج؛ (3) عدم وجود السلطة الإدارية/السيطرة على المتطوعين؛ (4) التركيز الغير أناني للعمل التطوعي. تحليل لمقابلات مع19 متطوع قائم على أساس المهارات يسلط الضوء على هوية ودور التوترات المتأصلة في التطوع المهني ويخدم كأساس لإقتراح لطريقة جديدة لتصور التطوع يتميز بأطياف التوتر بدل من العدسة التقليدية “لا تعمل .”

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that about 62.6 million Americans over the age of 25 volunteered through or for an organization at least once between September 2014 and September 2015. This means that about 25.9% of the over 25 adult population in the USA volunteered at least once last year (Bureau of Labor Statistics—US Census Bureau 2016). Because the Bureau of Labor Statistics only counts those who volunteer with or through a nonprofit organization (and do not include individuals who volunteer in more informal manners), the number of Americans volunteering in a broad sense is even higher. While the most recent comprehensive report found that the majority of volunteers in the USA do not perform service activities that relate to their professional or occupational skills, a small but significant percentage of volunteers (ranging from 7 to 23% of people volunteering from within a particular industry, depending on the industry/occupation of the volunteer) do volunteer to provide professionally related skills-based service (Corporation for National and Community Service- Office of Research and Policy Development 2008).

The Corporation for National and Community Service defines professional skills-based and pro bono community service as overlapping forms of service. Both types of service involve “the practice of using work-related knowledge and expertise in a volunteer opportunity” (Corporation for National and Community Service 2014). The phrase pro bono is often associated with the legal profession’s practice of providing free legal services to person(s) of need, but skills-based service includes a wide variety of activities, including teachers volunteering as tutors, nurses volunteering at a free clinic, web developers making Web sites for a nonprofit organization, or logistics experts helping food banks improve their inventory system. In this essay, pro bono service will be assumed to be a smaller subset of the larger category of skills-based service. In all of these situations, the individual volunteer is providing skills or service that are included in their occupational job description and for which the recipient nonprofit organization or client would otherwise have to pay. This is an important subset of volunteering, not only because of the number of volunteers involved, but because this subset of volunteering provides critical infrastructure and service capacity building for nonprofit organizations that could not otherwise afford them (Corporation for National and Community Service 2014).

Since Lewis’s (2005) seminal call for organizational communication scholars to study nonprofit organizations, a growing body of research has focused on the characteristics and motivations of volunteers, volunteer satisfaction, volunteer retention and turnover, effectiveness of volunteers, and expectations of volunteers (see Haski-Leventhal and Bargal 2008; Kramer et al. 2013). Yet, current definitions of volunteers in the literature emphasize “traditional” volunteering in which a person volunteers doing something other than his/her professional work. As a result, our understandings of volunteer recruitment, socialization, management, and impact are all shaped by what we consider volunteering to be. This paper considers the particular case of the skills-based volunteer in order to explore the limitations present in our current theorizations of volunteering. Specifically, this paper draws on in-depth interviews with 19 skills-based volunteers to examine the identity and role tensions inherent in skills-based volunteering and to propose a new way to visualize volunteering characterized by spectrums of tension rather than by the traditional lens of “not work.”

Defining Volunteer

Most scholars of volunteerism employ three criteria for defining a volunteer: the volunteer (1) performs tasks with free will, (2) receives no financial gain and (3) acts to benefit others (see Lewis 2013; McAllum 2014). Like the US Bureau of Labor Statistics definition above, typically these definitions are operationalized to include “planned prosocial behaviors that benefit strangers and occur within an organizational setting” (Penner 2002, p. 448). Typically, organizational volunteering is further defined as “proactive (e.g., signing up to serve meals at a shelter every Sunday) rather than reactive (stopping to help an accident victim after a car accident)” and therefore entails planned commitment of time and effort (Lewis 2005, p. 258).

Scholars, however, have begun recognizing that these traditional definitions of volunteering are limited and limiting in the face of the reality of volunteer work. These definitions ignore “a vast array of volunteer roles involving service to membership organizations, professional associations, sports/civic/school organizations (i.e., serving those we know well), fine arts volunteers, and those with questionable social ethics (e.g., volunteering to support a hate-group’s efforts to spread stereotypes” (Lewis 2013, p. 6).

As a result, more sophisticated definitions of volunteering have focused on the ways volunteer work is organized. For example, Pearce (1993) noted that volunteer work is more piecemeal and part-time, their relationships are less strong and more limited, and feedback is limited or nonexistent. Ashcraft and Kedrowicz (2002) added that volunteers are often less credentialed, receive little job training, are provided with few development opportunities and frequently work alone or off-site. Yet, even these definitions are limited, given that some volunteers are anything but piecemeal or part-time and that professional skills-based volunteers are often, by definition, more credentialed and trained in their particular skill set than anyone else (paid or unpaid) in a particular nonprofit organization. Lewis (2013) argues that in some ways, our study of volunteering has been subject to the stereotypes of the unpaid, altruistic volunteer in a traditional social service role (e.g., serving in a food kitchen), and so ignores the large number of volunteer roles that challenge that conception.

Challenging Volunteer Through Skills-Based Volunteerism

There are four theoretical conceptions of volunteering widely present in the volunteerism literature that may be most explicitly challenged by skills-based volunteering: (1) the bifurcation between work and volunteer activity; (2) low barriers to volunteer entry and exit; (3) the lack of managerial power/control over volunteers; and (4) the altruistic focus of volunteer work.

Bifurcation Between Work and Volunteer Activity

Similar to how the nonprofit, nonstatutory, or nongovernmental sector is most often defined in terms of what it is not, dominant definitions of volunteering define volunteering in comparative terms that accentuate how it differs from full-time paid work (McAllum 2014). Specifically, organizational communication scholarship has described volunteer relationships and work as “notably different from other types of public/professional/paid work” (Scott and Stephens 2009, p. 388). At times, this bifurcation has been operationalized as paid work and unpaid work, in which volunteer activity is unpaid work chosen by the individuals themselves, and which is carried out within the framework of an organization to assist individuals to which they have no familial or contractual obligation (see, for example, Erlinghagen and Hank 2006). In some ways, this distinction has been meaningful in helping to explore the full volunteer experience. As Ashcraft and Kedrowicz (2002) point out, organizational communication theory has tended to treat paid, full-time, permanent employees as the universal relationships between member and organization. Recognizing volunteers as not-employees can be instrumental in theorizing how things like empowerment function for volunteers. The problem emerges in that the tendency to define volunteering in terms of its similarities and differences to employment has fostered a number of binary oppositions in the literature. When work and volunteering are bifurcated into separate and nonoverlapping spheres, our theorizing can and does ignore instances where volunteers’ engagement can exist as both work and volunteer. Skills-based volunteering asks us to take more seriously extant communication scholarship that positions volunteers in an uncertain and ambiguously defined “third space” or “third place” (McNamee and Peterson 2014, p. 215).

Low Barriers to Volunteer Entry and Exit

One of the most notable ways that volunteering is positioned in the literature as not-employment is through the attention to volunteers’ low barriers to organizational entry and exit. In terms of organizational entry, Omoto and Snyder (2002) explain that volunteerism involves people freely choosing to help others in need and that acts of volunteering are typically ones that have been actively sought out by the volunteers themselves rather than solicited by an organization. Omoto and Snyder (2002) also add that “because volunteers typically help people with whom they have no prior contact or association, it is a form of helping that occurs without any bonds of prior obligation or commitment to the recipients of volunteer services” (p. 847).

In terms of organizational exit, traditional definitions of volunteering also assume that volunteers have virtually consequence-free opportunities for organizational exit. For instance, Iverson (2013) claims that “volunteer labor is free to leave” (p. 48, see also Hager and Brudney 2004). This ease-of-exit scenario seems to be primarily linked to the definition of volunteers as unpaid. For instance, McNamee and Peterson (2014) explain that unlike paid employees, who may take on and persist in negative experiences for the sake of pay, volunteers have no financial remuneration and thus are perceived as more able to leave without consequence. This ignores those volunteers who might actually accrue some financial remuneration (McBride et al. 2011). McNamee and Peterson also acknowledge that for some volunteers, payment status might not be particularly salient (for example in the case of volunteer firefighters), but they do not in their study explore how remuneration’s lack of salience might affect the ease of organizational exit. Overall, these studies largely ignore the potential mediating factor of the profession. They do not fully investigate whether an individual who is volunteering as a member of his/her profession (with his/her professional skill set) maintains the low barriers to entry/exit theorized in the literature.

Lack of Managerial Power/Control Over Volunteers

As a consequence of the perceived low barriers to entry and exit, the literature on volunteer management typically cautions that volunteer organizations will lack managerial control over volunteers. Wilson and Pimm (1996) noted that since volunteers can exit a nonprofit organization with relative ease and without financial penalty, the “conventional levers of management—control and direction—are either lost or so diluted as to be accepted or ignored according to mood and condition” (p. 25). The result of this thinking, according to McAllum (2013), is that “organizations cannot control volunteers” (p. 386).

A slightly more optimistic view in the literature is that volunteers might be managed if volunteer organizations are able to identify and meet volunteers’ needs (McAllum 2013). For instance, Hager and Brudney (2004) explain that volunteers must be cultivated rather than controlled. Iverson (2013) elaborates that cultivation focuses on creating the right environment for volunteers to meet organizational expectations and using encouragement rather than traditional, direct forms of control. Overall, however, the literature seems to agree that volunteer management is a “precarious yet highly consequential task” given the lack of traditional mechanisms of control (McNamee and Peterson 2014, p. 219). However, these existing studies do not fully investigate whether an individual who is volunteering as a member of his/her profession still exists outside of traditional power and control mechanisms in volunteer agencies.

Altruistic Focus of Volunteer Work

Finally, a significant component of much of the current volunteer literature is the assumption that the volunteering must be done for altruistic reasons. Altruism is often first operationalized in the literature as a lack of remuneration or pay (see Handy et al. 2000; Kramer et al. 2013; Musick and Wilson 2008). Volunteering, under these guidelines must be done for motives other than financial reasons (and thus is not work).

Volunteering in traditional definitions also requires altruism in that the volunteer work must be to the benefit of others and not to the benefit of the person doing the volunteer service. Net-cost theory explains how people judge the degree to which a volunteer is “pure.” The net-cost of any volunteer situation is the “the total cost minus total benefits to the volunteer” (Handy et al. 2000, p. 45). Musick and Wilson (2008) explain net-cost theory this way, “Purity of motivation becomes the template against which individual acts are compared and volunteer status is denied to those motivated primarily out of self-interest” (p. 17).

Yet, altruism as a criterion for volunteerism neglects a large segment of volunteer work. As Lewis (2013) explains, there has not yet been significant study of a variety of volunteers including pro bono professionals, coaches, or volunteering in the context of membership organizations that “may be less about altruism and…more about paying the dues of belonging to the organization or participating in the activities enabled by the organization” (p. 17).

Therefore, in this study, I consider the particular case of the skills-based volunteer. Specifically, I wanted to understand how skills-based volunteers describe their identity as skills-based volunteers and the role tensions inherent in their volunteering experience. As such, I was guided by the following research question:

RQ: How do skills-based volunteers characterize what it means to be a skills-based volunteer and the identity and role tensions that characterize that experience?

Method

Interpretive research is grounded in the belief that individuals each experience and interpret their reality in unique ways (Baxter and Babbie 2004). Interpretive researchers seek to examine specific experiences or contexts deeply to more fully understand the meaning that the participants hold (Baxter and Babbie 2004; Lindlof and Taylor 2002). In the current project, I adopt an interpretive framework as I seek to understand how skills-based volunteers talk about their volunteering.

Participants

To participate in this study, respondents had to: (1) be at least 18-year-old, and (2) have volunteered using professional/job-related skills for at least one nonprofit organization over the last year. A sample of individuals who identified as having been skills-based volunteers who fit these criteria was obtained using a network sampling technique.

For this study, I interviewed 19 skills-based volunteers. Of those volunteers, eleven were female and five were male. The participants’ ages ranged from 30 to 59 years, with an average age of 37.8 years. The participants represented a range of occupations/professions in their paid working lives. Eight of my participants described occupations broadly characterized as in Communication and the Arts (including Graphic Design, Web Design and Social Media, Public Relations, and Creative Directing). Six of my participants described occupations broadly represented as Allied Health, in that all of their professions required at least some degree of medical/health licensing from the state in which they practiced (including Dental Hygienists, Athletic Trainers, and a Doula/Midwife). Three of my participants were working in Law as lawyers who had passed their state’s licensing/bar exam. One participant characterized his paid occupation as a Computer Software Engineer, and one participant described her occupation as Community Organizing.

Procedures

A semi-structured interview protocol was designed to elicit participants’ communication about and around skills-based volunteering. The interview protocol included open-ended questions asking for stories about their communication with an in skills-based volunteering contexts, their communication with paid work colleagues about skills-based volunteering, as well as communication with and in nonskills-based volunteering contexts. The participants were also asked how they defined skills-based volunteering and asked to tell stories of how that volunteering was similar to and different from both nonskills-based volunteering and paid work.

Using the protocol as a guide, I conducted individual interviews that were tape-recorded. Overall, 19 interviews ranged from 21 to 60 min and averaged 38 min in length. Once collected, the interviews were transcribed near-verbatim (filler words which did not alter meaning were omitted). This resulted in 220 pages of single-spaced text for analysis.

The data were analyzed using data reduction and interpretation by following the six-step thematic analysis process outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). I first engaged in a repeated close reading of the transcripts. Second, I inductively coded the data by jotting down themes which appeared to be recurrent across the transcripts. Third, I collated coded data into or themes, broadening and narrowing as necessary to get at the underlying meanings of the data. Fourth, I checked to ensure that all of the potential themes fit the data in the coded extracts. Fifth, I defined and named the themes, and finally I selected vivid, compelling extracts from the data to represent each theme in the analysis below. Results were shared with one of my participants as a member check to ensure resonance and clarity (Lindlof and Taylor 2002).

Results

This study was guided by the research question: How do skills-based volunteers characterize what it means to be a skills-based volunteer and the identity and role tensions that characterize that experience? Three central themes emerged: (A) skills-based volunteering as Not Work and Work; (B) skills-based volunteering as Voluntary and Not Voluntary; and (C) skills-based volunteering as Professional and Not Professional.

Not Work and Work

Because skills-based service, by definition, involves “the practice of using work-related knowledge and expertise in a volunteer opportunity” (Corporation for National and Community Service 2014), participants in this study saw skills-based volunteering as existing in a space of both Work and Not Work. As John, a 37-year-old software engineer, explained, “You’ve got your paid work on the one hand…Then on the other end of the spectrum, we’ve got the pure volunteer work… Then somewhere in the middle you’ve got the skills-based volunteering.” He then went on to say “I think it’s hard to say it [skills-based volunteering] is distinct from either of those things just because it’s almost like a mix of the two, or a blend.”

Many of these participants described skills-based volunteer opportunities that were Not Work but that came with additional benefits that enhanced both their volunteering experience and their professional lives. For instance, bringing professional skill sets to the organizations made them more effective as volunteers. Karen, a 33-year-old attorney, explained that in a previous nonskills-based volunteer role, she couldn’t help thinking to herself “You know, me knocking on doors is not the highest use of my time.” When asked to explain, she elaborated that the “really nice thing about pro bono work is that it does make use of your specific skills and education that are, I think that my time doing that is more valuable to somebody.” Linda, a 32-year-old Doula, agreed, saying “I feel more effective when I’m volunteering within my profession because it’s something that I actually know… I feel more effective and more useful.” In that way, skills-based volunteering meant that their professional skills made them better volunteers.

Second, participants saw skills-based volunteering as a way to build, play with, or refine professional skill sets of use to them in their paid work. As Mary, a 38-year-old graphic designer, explained that when choosing skills-based volunteering projects, she would “take on a project so that I can practice a specific skill set or try something out or if I think the client or organization will be open to something a little bit more experimental.” Robert, a 39-year-old creative director, echoed similar ideas, saying, “I’m able to go in and do some stuff that I wouldn’t necessarily do or do more stuff that I’m trying to learn. It builds my confidence and my skills in that area.” In this vein, more than one participant saw professional volunteering as a way to put into practice skills that might otherwise only be learned through textbooks or theoretical examples. For instance, Nancy, a 59-year-old dental hygienist and professor, talked about her time volunteering as a Hygienist at the Veterans Affairs clinic. She explained “We get the opportunity, unfortunate opportunity, of seeing things like colon cancer, addiction problems, things like mental health issues, those types of things that we get to see in the textbooks as the worst of the worst, a lot of things we experienced when we’re doing the volunteering.” In those ways, professional volunteering functioned as work and volunteering, by allowing space for professionals to use and refine their skills in a way that benefited both the nonprofits for whom they volunteered and their paid workplaces.

However, the people I interviewed also felt that skills-based volunteering in a unpaid environment could force them back into work-like relationships that could undermine the value they received from volunteering. For instance, many of these skills-based volunteers described seeking out more diverse nonwork-related volunteering situations and becoming pigeon-holed into skills-based volunteering once their professional identity(ies) was discovered. Patricia, a 34-year-old graphic designer and artist, explained that as part of her graphic design practice she does a lot of spreadsheet and computer programming work. One time she attempted to volunteer for a food bank making lunches as way to spend time away from her professional world of graphic design. But, she continued that “If I’m supposed to be in a place to make sandwiches and they find out I can use a spreadsheet, all of a sudden I’m doing spreadsheets, when really all I wanted to do was make sandwiches.” Dorothy, a 36-year-old community organizer, agreed when she explained that she had sought out some art-themed volunteering activities because “I actually like to do crafty things.” However, when organizations learned of her community connections and organizational skills, she was often diverted to volunteer management activities. Dorothy explained “It’s not a good or bad thing, but a part of my own natural instinct goes unfulfilled because my skill and profession puts me over here.” Margaret, a 40-year-old associate professor of relational communication, summarized that being pulled into skills-based volunteering was hard because “I’m just doing more of the same thing that I do that’s paid labor.” In this way, skills-based volunteering, especially when the use of professional skills was unsolicited by the volunteer themselves, limited the ability of volunteers to engage in nonwork volunteering that might have been meaningful to them.

In this particular sample, volunteers reported both being sought out/recruited by nonprofit organizations specifically for their professional/job skill sets and volunteers reported actively seeking out volunteer work (both related and not-related to their professional/job skill sets). There were situations (like those described by both Dorothy and Margaret above) in which skilled volunteers sought to volunteer at organizations that often welcome nonskilled volunteer workers. The particular frustration described above emerged, then, when the volunteer had hoped to do nonskilled (or non-job-related) volunteer work and had sought out that type of volunteer work only to be pushed into skilled volunteer work by the voluntary organization.

Additionally, core to many theoretical conceptions of the difference between work and volunteer is the idea that volunteers can exit a nonprofit organization with relative ease and without financial penalty (see, for example, Wilson and Pimm 1996). Yet, many of these skills-based volunteers explained that their skills-based volunteering work had such real, material consequences for their paid work that they did not have such flexibility. Initially, because these volunteers were, by definition, volunteering with their professional skill sets, the volunteer work could not be substandard or left incomplete due to the consequences for their professional reputation. As Barbara, a 33-year-old web designer, indicated that if she turned in an inferior project or quit a job, “then it could reflect on me poorly in my current job or potential jobs.” Michael, a 37-year-old digital marketing and social media analyst, agreed saying, “I think that could definitely have a negative impact, if you didn’t meet deadlines and people started talking in the community.”

For these volunteers working in the medical and law industries, inferior skills-based volunteer work carried even higher potential consequences. As Karen, a 33-year-old lawyer, explained that once you agree to professionally volunteer as a lawyer, you can’t walk away from a project or a client without petitioning the court. She notes, “You can’t abandon the client, and often, you can’t, even if you find the client another attorney, you can’t just automatically withdraw. You often have to get permission from the court to withdraw, and sometimes they won’t grant it.” Furthermore, as Karen explains, “You can absolutely commit malpractice for a pro bono client, and pro bono clients have sued attorneys for malpractice before. It’s serious business in a way that volunteering at a food bank or something, while being important and valuable, is less tied to your regular professional life and your livelihood.”

Similarly, for the participants working in the medical field, volunteering with their medical skills raised professional liability issues. As Helen, a 34-year-old athletic trainer and assistant professor, explained, “Since it’s medical coverage usually we have to have our own professional liability insurance for self-protection. If we do something wrong we can be in trouble for it.” Susan, a 44-year-old athletic trainer and professor, agreed and emphasized that if she provided poor quality care in a skills-based volunteering situation that she was legally liable and she could lose her state medical license. She indicated that it did not matter if you weren’t being paid for your skills-based volunteer work because “you have a separate duty to the state [of State Name] because of your medical license.” Thus, though skills-based volunteering was by definition Not Work, it also implicated and replicated Work.

Voluntary and Not Voluntary

Just as skills-based volunteering functioned for these participants in a space of Not Work and Work, skills-based volunteering also existed in a space both Voluntary and Not Voluntary. Traditionally, the Voluntary nature of volunteer work has been characterized as something that a volunteer might seek out or opt into (Omoto and Snyder 2002). The participants in my study did describe seeking out volunteering as an important part of their skills-based volunteer service. For instance, Susan, a 44-year-old athletic trainer and professor, explained she enjoys volunteering so “I seek them [volunteer opportunities] out.” Helen, a 34-year-old athletic trainer and assistant professor, similarly explained, “Usually what I do when I come to a new area is I’ll find out who the contact person is for the major events in the area and then ask to be on their Listserv so I get notified when they are looking for [volunteer] coverage.”

However, these participants were much more likely to describe being drawn into a skills-based volunteer experience was through the specific request of family, friends, or professional colleagues. For instance, Michael, a 37-year-old digital marketing and social media analyst, explained that of his most recent volunteer experiences, “I was contacted by all three of them… it was personal friends. They reached out to me.” When asked the difference between skills-based volunteering and other nonskills-based volunteering, Robert, a 39-year-old creative director, summarized:

Well, the non-professional volunteering is stuff that I will generally seek out or have a personal or family connection to, right? If the kids are going to play baseball, I might as well be their coach. If scouting was important to me, I want the kids to do scouting, I need to be involved. Whereas, the professional stuff is usually people seeking me out. I think that’s about it.

Being connected to volunteer opportunities through personal connections created for many of these skills-based volunteers a social obligation framework that made it difficult to say “no.” For instance, when asked how she became involved in skills-based volunteering experiences, Mary, a 38-year-old graphic designer, said “for the most part it was either a direct factor, someone who knew me as a friend or a colleague, or it was someone who just heard about me and then requested, often through another friend.” After a longer story, I then asked it if the fact that it was a favor created a sense of obligation. Mary exclaimed “Exactly. Yeah, it just feels very different. I fire clients. I’ve never fired someone I was volunteering for because it’s almost always that kind of situation.” This sentiment was especially true for people who were connected to skills-based volunteering opportunities through their paid work. For instance, Robert, a 39-year-old creative director, explained “If my boss is asking me [to volunteer] that’s always really high up there. If my boss asks me to help, then I’m always going to help.” In those instances, skills-based volunteering felt not entirely voluntary.

In fact, several of these skills-based volunteers described a system in which their workplaces actively incentivized volunteering in a skills-based capacity. For instance, James, a 35-year-old patent/intellectual property lawyer, explained that at his law firm, associates were required to complete a certain number of billable hours of work a month. But, at “my former firm, they used to be big on pro bono. You actually get billable hour credit one to one ratio for pro bono work. If you’re, anyone who’s light on work or whatever, they could always do pro bono to help get their hour and a count toward their bonus, so that was pretty nice.” Similarly, Karen, a 33-year-old lawyer, explained that most lawyers in her office also engaged in skills-based volunteer work:

In part because we operate under a billable hour structure, actually, billable 6 min. Yeah, it’s a nightmare. The firm will treat a certain amount of pro bono work for associates as billable. There’s an allotment in your billable hour structure that some of it counts towards the number of hours you need to make for the year. There’s a really strong incentive to do it.

However, these work incentives at times created the impression that volunteer work was Not Voluntary. Karen continued that lawyers in her office were given a target goal for the number of pro bono or skills-based volunteer hours they should complete each year. She then explained, “I think if you don’t make it, I’ve heard at least that if you don’t do the hours that you’re asked to do, you get an email from the CEO of the firm at the end of the year.” Thus, not completing skills-based volunteer hours could hurt the lawyer’s reputation and standing in their paid work. In the end then, these volunteers were frequently drawn into skills-based -based volunteering in ways that did not feel entirely Voluntary. As a result, though professional volunteering was by definition Voluntary, it also functioned in NonVoluntary ways.

Professional and Not Professional

Finally, skills-based volunteering exists in a space of Professional and Not Professional. Overwhelmingly, the skills-based volunteers I interviewed enjoyed professional volunteer work (work that engaged the same skills as their profession/career) in part because it allowed them a space to feel “professional” in their volunteer work. When asked about the differences between skills-based volunteering and other nonskills-based volunteer experiences, Mary, a 38-year-old graphic designer, explained “I think the major difference is that I really feel like I have the expertise in the professional capacity… Whereas I probably could help people in those other ways too, but it’s a uniqueness or a specialness that I can bring [to skills-based volunteering] that other people can’t.” Similarly, when describing the differences experienced when volunteering in a nonskills-based situation, Susan, a 44-year-old athletic trainer and professor, explained that in nonprofessional volunteering “I have a lot less confidence.”

Nancy, a 59-year-old dental hygienist and professor, explained that bringing professional skills to a volunteering situation led to her being automatically trusted and treated as a professional authority figure in a way that did not happen in other types of volunteer environments. She explained:

When I’m in a dental situation, I’m usually in uniform. I’m in scrubs, I have a lab coat on, I have name tag that identifies who I am and what I do. They come in and look to me for the authority. When I’m out of the dental setting, I don’t have that same authority, I have to earn it, where I automatically have it in the other. I guess they’re not sure of me, my role, what I’m doing, and so I have to earn it.

In skills-based volunteering roles then, skills-based volunteers often entered organizations with some degree of the status and credibility that they were used to in their professions.

On the other hand, many of the skills-based volunteers in my study believed that their very act of skills-based volunteering served to undermine their clients’ views of their professions. Many of the professionals I interviewed said that voluntary clients treated them as less expert or less professional because they were getting services for free. Linda, 32-year-old doula, explained that “a lot of what doulas do is coaching and giving advice, and if you’re not paying for it, then you’re not going to take the advice as seriously.” Patricia, a 34-year-old graphic designer and artist, agreed and elaborated that “clients who have chosen to pay for work have already had some kind of education about the value of that thing or they wouldn’t have chosen [to pay].” In contrast, Mary, a 38-year-old graphic designer, continues “If someone has an organization and they’re looking around for someone to do design for free and they make that ask, there’s that expectation that what the designer does isn’t really valuable.”

In addition to potentially undermining their own expert or professional status, many of the skills-based volunteers I spoke with worried that skills-based volunteering undermined the future of their profession by communicating that the services could or should be provided without pay. Helen, a 34-year-old athletic trainer and assistant professor, explained “I guess if you’re always willing to work for free that’s obviously going to hurt you because at some point you need to get paid.” Helen summarized “we have this conversation all of the time in our department—if you’re doing too good a job with too little then there’s no incentive for the entity to give you more.”

While devaluing your own ability to be paid for your professional skills is obviously undesirable, the participants in my study were generally even more worried that they were hurting the employability of their professions as a whole. Susan, a 44-year-old athletic trainer and professor, explained this as a logical implication of Helen’s concerns, saying:

For example, [an athletic training] clinic wants a high school contract and so they say, ‘We’ll do it for free.’ It does, it devalues it in a way and then what if that clinic can’t afford to do it for free anymore? Then the next clinic comes in and says, ‘We’ll do it for $10,000.’ The high school will respond ‘Well we’ve been getting it for free for 5 years why should we pay? We never had to pay before.’

Linda, a 32-year-old doula, expressed a similar sentiment saying, “There’s a lot of lashback for doing free births. They think that it devaluates the industry as a whole.” In the end then, many of the volunteers in this study actively enjoyed skills-based volunteering because they both felt like competent, authoritative professionals. On the other hand, these skills-based volunteers were very conscious of the ways in which skills-based volunteering undercut both their own professional value and the public value of their professions. This resulted in an ongoing tension between Professional and Not Professional in skills-based volunteering work.

Discussion

Since Lewis’s (2005) seminal call for organizational communication scholars to study nonprofit organizations, research has increasingly focused on a wide range of issues unique to the volunteer experience in organizations (see Haski-Leventhal and Bargal 2008; Kramer et al. 2013). Yet, current definitions of volunteers and volunteering largely centered on positioning volunteers as not paid work. The result is that volunteers are prominently defined by (1) the bifurcation between work and volunteer activity; (2) their low barriers to volunteer entry and exit; (3) the lack of managerial power/control over volunteers; and (4) the altruistic focus of volunteer work.

This study reveals, however, that these characterizations of the volunteer experience are overly simplistic. First, as the participants in this study described, work and volunteer activity do not always exist in separate and mutually exclusive spheres. These skills-based volunteers brought their professional skill sets to volunteering in a way that enhanced the nonprofit organization they served while simultaneously letting the volunteers refine skills to help their own professions/paid work. In a positive way, representing their professions while volunteering often afforded these volunteers a sense of respect from their nonprofit clients. Yet, these skills-based volunteers were often pushed into work-like “jobs” at nonprofit organizations, even when they sought out other “forms” of volunteering. Since skills-based volunteering is, at its core, volunteer work for which the organization would otherwise have to pay (Corporation for National and Community Service 2014), volunteer organizations may push volunteers with professional/job-related skill sets to engage as skills-based volunteers so that the nonprofit organization can avoid paying an employee to do that work. As a result, volunteer work and paid work may increasingly exist in overlapping rather than bifurcated spheres. In all of these situations, work and volunteering overlapped and blurred in significant ways for these volunteers.

Second, many volunteers in this study described their participation in volunteering as not entirely based in free will. Many of the volunteers were recruited specifically for the particular professional skill set that the nonprofit organization needed. Most of that recruitment was done through personal and workplace social networks, which fostered an obligation framework that many skills-based volunteers felt made them beholden to volunteer. Moreover, some paid workplaces actively encouraged (and, in some cases, all but required) skills-based volunteering in a way that felt involuntary. As a result, these narratives position skills-based volunteering as different from our traditional conceptions of barrier-free volunteer entry.

Third, professional expectations and legal requirements meant that barriers to skills-based volunteer exit are real and at times substantial. When volunteering within their profession, none of my volunteers believed that they could leave the volunteer work incomplete or could turn in low quality work without it having implications for their professional reputation and paid work. Further, legal requirements on some professions (including legal and medically licensed professions) meant that a skills-based volunteer could not abandon or underperform for a nonprofit client without the risk of malpractice. Moreover, because the spheres of work and volunteer are mutually influential, the choices by these skills-based volunteers to volunteer had real implications both for their own ability to be paid for their skill sets and for their professions to be deemed worthy of paid work status.

As a result, I propose that this study demonstrates the need for a tension-centric model of volunteering. Organizational communication scholars are increasingly concerned with the various tensions, contradictions, and double binds that appear to be endemic to organizational life (Trethewey and Ashcraft 2004). Yet, our volunteering literature prominently defines volunteering and work in black and white, work and not work (or paid and unpaid work) terms.

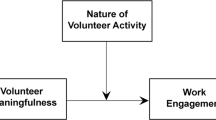

If we began theorizing volunteering as a domain characterized by three prominent tensions: the tensions of work and not work, the tensions of voluntary and not voluntary, and the tensions of professional and not professional, we could much more productively understand the spectrum of tensions that characterize each act of volunteering. Figure 1 indicates a preliminary visualization of a more nuanced way we could examine volunteering.

The tension of Work and Not Work would recognize that while some forms of volunteering are “notably different from other types of public/professional/paid work” (Scott and Stephens 2009, p. 388), other forms of volunteering may be, in the case of a skills-based volunteer by definition, a replication of paid work in a voluntary context. Even though some scholars have worked to develop a more nuanced characterization of volunteering as a type of “unpaid work” that might be contrasted with “paid work”, this characterization still (1) presumes a bifurcation (rather than overlapping spheres between paid and unpaid work) and (2) insists that to be volunteering that unpaid work must be “provided to parties to whom the worker owes no contractual, familial, or friendship obligations” (Wilson and Musick 1997, p. 694). Breaking down this binary of work/not work and of paid/unpaid work (as it is currently understood) would also allow us as researchers to more specifically expand definitions of volunteer as piecemeal and part-time (Pearce 1993) to also include those who volunteer in more systematic ways (even as a vocation). Disrupting this binary might also help recognize that, as in the case of many skills-based volunteers recruited to voluntary organizations by their bosses, friends or family, volunteering can occur in contexts in which the volunteer does have contractual, familial or friendship obligations with those with whom they volunteer. This tension of work and not work highlights that while volunteering may indeed be a third space (McNamee and Peterson 2014), we must continue to conceptualize that space as substantially overlapping both work and home life.

The tension of Voluntary and Not Voluntary would recognize that while some volunteering is certainly unpaid, based in altruism, and guided by free will (Lewis 2013), in other cases students are required to volunteer as part of a class requirement (Botero et al. 2013) or individuals are required to volunteer as part of a court-ordered community service program (Carson 1999). In this study, skills-based volunteers were often encouraged (and at times coerced) into volunteering by their paid employers. The tensions on this spectrum have important implications for volunteer entry and exit as well as for volunteer management (power and control)

The tension of Professional and Not Professional would recognize that while some volunteers are certainly less credentialed and have less job training than paid nonprofit staff (Ashcraft and Kedrowicz 2002), in other scenarios skills-based volunteers may, by definition, bring their professional training and skills to an organization lacking those resources. Moreover, this tension of the professional and nonprofessional has significant implications for who is seen as professional by clients and how professions (as deserving of pay) are socially understood.

These tensions, moreover, should not be understood as simply linear. As this study demonstrates, a particular volunteering activity might exist in tensions of both professional and nonprofessional, for example, at the same time. Future exploration would be needed to develop this preliminary visualization more fully into a model of volunteering. But, a more nuanced understanding of volunteering (including volunteer recruitment, socialization, management, and impact) can only be possible when we move beyond the volunteering as not work frame.

Though the richness of their stories made nineteen interviewees an acceptable number for this exploratory study, certainly future research must continue to examine the experiences of skills-based volunteers as well as other volunteers who do not easily fit our traditional conceptions of volunteering. Furthermore, these particular respondents only included people who identified as currently in the workforce. Given the substantial number of older adults who choose to volunteer after retiring from their work-lives, additional research should explore the perspectives of that subset of skills-based volunteers. Finally, it is notable that all of the participants in this study had college degrees (and many, though not all, had graduate/post-secondary degrees). This is consistent with research that indicates that higher levels of educational attainment correlate to higher levels of charitable work/charitable giving (Brown and Ferris 2007). Skills-based volunteers may on average have even higher educational attainment than nonskills-based volunteers, though this study did not explore that question. Yet, many potentially valuable skills (e.g., plumbing, electrical work, automotive repair) do not require college degrees. Thus, future studies of skills-based volunteering could expand on the perceived educational expectations of this type of volunteer work. Nevertheless, this study highlights the identity and role tensions inherent in or skills-based volunteering and the need for a new definitional model of volunteering characterized by spectrums of tension rather than by the traditional lens of “not work.”

Change history

11 April 2018

The PDF version of this article was reformatted to a larger trim size

References

Ashcraft, K. L., & Kedrowicz, A. (2002). Self-direction or social support?: Nonprofit empowerment and the tacit employment contract of organizational communication studies. Communication Monographs, 69(1), 88–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750216538.

Baxter, L. A., & Babbie, E. (2004). The basics of communication research. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Botero, I. C., Fediuk, T. A., & Sies, K. M. (2013). When volunteering is no longer voluntary: Assessing the impact of student forced volunteerism on future intentions to volunteer. In M. W. Kramer, L. K. Lewis, & L. M. Gossett (Eds.), Volunteering and communication: Studies from multiple contexts (Vol. 1, pp. 297–319). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brown, E., & Ferris, J. M. (2007). Social capital and philanthropy: An analysis of the impact of social capital on individual giving and volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764006293178.

Bureau of Labor Statistics—US Census Bureau. (2016). Volunteering in the United States—2015 [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/volun.htm.

Carson, E. D. (1999). Comment: On defining and measuring volunteering in the United States and abroad. Law and Contemporary Problems, 62(4), 67–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/1192267.

Corporation for National and Community Service. (2014). Toward a New Definition of Pro Bono: Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved from https://www.nationalserviceresources.gov/pro-bono-faq#.VCmfQGddXl4.

Corporation for National and Community Service- Office of Research and Policy Development. (2008). Capitalizing on volunteers’ skills: Volunteering by occupation in America Retrieved from Washington, DC: http://www.nationalservice.gov/pdf/08_0908_rpd_volunteer_occupation.pdf.

Erlinghagen, M., & Hank, K. (2006). The participation of older Europeans in volunteer work. Ageing and Society, 26(4), 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X06004818.

Hager, M. A., & Brudney, J. L. (2004). Balancing act: The challenges and benefits of volunteers. Retrieved from Washington, DC: http://www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/411125_balancing_act.pdf.

Handy, F., Cnaan, R., Brudney, J., Ascoli, U., Meijs, L. M. P., & Ranade, S. (2000). Public perception of “who is a volunteer”: An examination of the net-cost approach from a cross-cultural perspective. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 11(1), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008903032393.

Haski-Leventhal, D., & Bargal, D. (2008). The volunteer stages and transitions model: Organizational socialization of volunteers. Human Relations, 61(1), 67–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707085946.

Iverson, J. O. (2013). Communicating belonging: Building communities of expert volunteers. In M. W. Kramer, L. K. Lewis, & L. M. Gossett (Eds.), Volunteering and communication: Studies from multiple contexts (Vol. 1, pp. 45–64). New York: Peter Lang.

Kramer, M. W., Lewis, L. K., & Gossett, L. M. (Eds.). (2013). Volunteering and communication: Studies from multiple contexts (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Lewis, L. K. (2005). The civil society sector: A review of critical issues and research agenda for organizational communication scholars. Management Communication Quarterly, 19(2), 238–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318905279109.

Lewis, L. K. (2013). An introduction to volunteers. In M. W. Kramer, L. K. Lewis, & L. M. Gossett (Eds.), Volunteering and communication: Studies from multiple contexts (Vol. 1, pp. 1–24). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Lindlof, T. R., & Taylor, B. C. (2002). Qualitative communication research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

McAllum, K. (2013). Challenging nonprofit praxis: Organizational volunteers and the expression of dissent. In M. W. Kramer, L. K. Lewis, & L. M. Gossett (Eds.), Volunteering and communication: Studies from multiple contexts (Vol. 1, pp. 383–404). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

McAllum, K. (2014). Meanings of organizational volunteering: Diverse volunteer pathways. Management Communication Quarterly, 28(1), 84–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318913517237.

McBride, A. M., Gonzales, E., Morrow-Howell, N., & McCrary, S. (2011). Stipends in volunteer civic service: Inclusion, retention, and volunteer benefits. Public Administration Review, 71(6), 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02419.x.

McNamee, L. G., & Peterson, B. L. (2014). Reconciling “third space/place”: Toward a complementary dialectical understanding of volunteer management. Management Communication Quarterly, 28(2), 214–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318914525472.

Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2008). Volunteers: A social profile. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (2002). Considerations of community: The context and process of volunteerism. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(5), 846–867. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764202045005007.

Pearce, J. (1993). Volunteers: The organizational behavior of unpaid workers. New York, NY: Routledge.

Penner, L. A. (2002). Dispositional and organizational influences on sustained volunteerism: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 447–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00270.

Scott, C. R., & Stephens, K. K. (2009). It depends on who you’re talking to…: Predictors and outcomes of situated measures of organizational identification. Western Journal of Communication, 73(4), 370–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570310903279075.

Trethewey, A., & Ashcraft, K. L. (2004). Special issue introduction. Practicing disorganization The development of applied perspectives on living with tension. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 32(2), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0090988042000210007.

Wilson, J., & Musick, M. (1997). Who cares? Toward an integrated theory of volunteer work. American Sociological Review, 62(5), 694–713. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657355.

Wilson, A., & Pimm, G. (1996). The tyranny of the volunteer: the care and feeding of voluntary workforces. Management Decision, 34(4), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251749610115134.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steimel, S. Skills-Based Volunteering as Both Work and Not Work: A Tension-Centered Examination of Constructions of “Volunteer”. Voluntas 29, 133–143 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9859-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9859-8