Abstract

Despite the benefits of volunteering to the individual, organization and community, the retention of volunteers within volunteer and not-for-profit organizations remains a significant challenge. Examining the motivations of individuals who have ceased their engagement in a volunteer organization may provide insights to improve retention rates. The perceptions of 64 volunteers formerly involved in an international volunteer organization were examined through community telephone interviews and online surveys. Results show that while volunteers valued their participation in the volunteer organization, their decision to cease engagement in the organization was driven by five major themes: ‘Work overload and burnout,’ ‘Lack of autonomy and voice,’ ‘Alienation and cliques,’ ‘Disconnect between volunteer and organization’ and ‘Lack of faith in leadership.’ Strategies to improve and refine organizational practice and culture may contribute to a strengthened membership and retention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Volunteering has been shown to produce significant enhancements to quality of life, providing a sense of satisfaction, purpose and improved outcomes in aging (Cattan et al. 2011; Chen 2016; Greenfield and Marks 2004; Warburton 2010; Warburton et al. 2007). In addition to the number of benefits to the volunteer themselves, at an organizational and community level, volunteers are often essential to the operations and functioning of organizations, making volunteers an invaluable resource (Volunteering 2015).

Despite the documented benefits of volunteering at the individual, organizational and broader societal levels, volunteer retention remains a significant challenge for volunteer and not-for-profit organizations (Harp et al. 2017). Understanding the motivations of volunteers to sustain their engagement in volunteer organizations and increasing retention rates of volunteers is a key focus for volunteer and not-for-profit organizations.

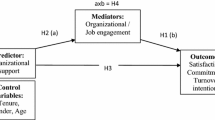

Attempts to understand the nature of volunteering, and therefore retention of volunteers within organizations, have focused on intrinsic motivators such as individual motives for volunteering, whether they be altruistic or egoistic (Veludo-de-Oliveira et al. 2015), as well as broader extrinsic and organizational factors (Curran et al. 2016; Harp et al. 2017; Wilson 2012). Conceptual frameworks of volunteer retention suggest that a volunteer’s decision to remain within an organization is dependent on their satisfaction and engagement, with these outcomes resultant of interactions between the organizational structure, the individual, and the tasks volunteers are required to undertake (Harp et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2007; Van Vianen et al. 2008). While intrinsic motivators such as social enjoyment and personal motives drive volunteers to first initiate contact with organizations, sustained retention of volunteers may be influenced more heavily by extrinsic factors. Long-term retention of volunteers may require greater opportunities to develop connections with peers and feelings of commitment to the organization (Hyde et al. 2016).

At a personal or intrinsic level, an individuals’ perceived fit between their personality and that of the prototypical organization member has a significant influence on their commitment to the volunteer organization (Van Vianen et al. 2008). Volunteering has been suggested to contribute to the development of a ‘volunteer’ identity, with the development of this self-concept possibly contributing to greater motivation to continue engagement with an organization (Van Vianen et al. 2008). In relation to this personal-organization fit, volunteers further enter organizations with implicit and explicit perceived expectations and understandings of the organization (Walker et al. 2016). Volunteers report higher satisfaction when these perceived expectations are met. Thus, the ability for organizations to fulfill these expectations may have significant influences on volunteer retention (Walker et al. 2016).

Research examining the extrinsic influences of volunteer retention has identified multiple factors including the provision of opportunities for learning and development (Newton et al. 2014), organization support (Walker et al. 2016), social inclusion (Waters and Bortree 2012) and opportunities for decision making (Waters and Bortree 2012) as particularly influential in determining an individual’s commitment and continued engagement with an organization. The importance of these factors is further influenced by volunteer gender (Waters and Bortree 2012). While motivations to continue engagement with a volunteer organization are largely driven by social inclusion and support for female volunteers, opportunities for decision making may be particularly influential for male volunteers (Waters and Bortree 2012).

It is clear that volunteer retention results from a complex interaction between personal and organizational factors. Though previous research provides insights into the dynamics of intrinsic and extrinsic factors underlying volunteer retention, the majority of these studies have been conducted with volunteers still engaged in voluntary organizations (Garner and Garner 2011; Harp et al. 2017; Hyde et al. 2016; Walker et al. 2016). Little investigation to date has examined the motivations of those who have ceased their engagement in a volunteer organization. Investigating the motives of volunteers who have discontinued their engagement in volunteering may provide insights into the reasons why these individuals cease volunteering and assist in identifying strategies to improve retention of these individuals.

Background to Research

This research project was undertaken through an international volunteer organization comprising of over 1.2 million members worldwide, with approximately 30,000 volunteers engaged in the Australian branches of the organization. The organization is considerably long-lived with a history of strong traditions and routines. Volunteer clubs within this organization fall into geographically defined regions, with each led by a nominated person. Clubs, however run independently, led by a club president and club office holders. Clubs engage in a large range of activities including community service projects, youth development and international development. For the current study, a focus was placed on a region containing 48 clubs.

Method

A retrospective mixed methodology (Terrell 2012) that collected both quantitative and qualitative data was used. Ethical approval for the study was obtained through Curtin University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2016-0413).

Participants and Recruitment

Past members of a national community service organization were the participants of interest in this study. Convenience (Etikan et al. 2016) and opportunistic sampling (Coolican 2014) were used in this project whereby eligible participants were sourced from a database provided by senior officials of the volunteer organization. A passive opt-out method was used in which eligible individuals were informed that they would be contacted by a research team, unless they informed the organization that they did not want to be contacted. Participant inclusion criteria stipulated that the individual be a full member associated with the volunteer organization in the between the years of July 2013–July 2016; be contactable via a current email address and/or phone number; and have the ability to comprehend and speak English. Participants were excluded if they held an ‘honorary’ membership and a known incapacity that would prevent participation. A total of 374 eligible participants were identified as contactable from the provided database (291 participants via email and 83 via telephone). Of the 83 eligible participants contacted via telephone, 34 declined to participate and 30 were un-contactable due to inaccurate data (e.g., out-of-date phone numbers). Of the 291 members emailed, 45 responded to the online survey. Thus, the 64 former volunteers represent the sample analyzed in this study. Table 1 contains demographic information of the respondents.

Data Collection

Telephone interviewing (Musselwhite et al. 2006) and online surveys were used to understand reasons underlying why former members ceased engagement with the volunteer organization. Telephone interviews were offered to eligible participants who had provided a contact number. Interviews were approximately 10 min in length and conducted by a psychologist. Participants provided verbal consent prior to the continuation of the interview. A semi-structured interview guide was utilized, consisting of demographic, open-ended and Likert-scale-type questions. Interviewee responses were documented using an online Qualtrics database (Qualtrics 2017). During the interview process, the interviewer kept personal notes and member-checking was undertaken and during the interviews to ensure accuracy of the results (Krefting 1991). A verbal summary of interviewee responses was also provided at the end of the interview to correct any misunderstandings. The same process was used for the online survey; however, it was not possible to undertake member-checking on the responses. Former members who provided emails were sent out an email invite of participation with the online survey link (same questions as the telephone interview) with participant information embedded within the email. Open-ended questions in both interview and online surveys pertained to their motivations to join the volunteer organization, the benefits gained from their involvement and why they ceased their engagement with the volunteer organization. Likert-scale questions were presented on a 5-point scale with questions relating to how much the volunteer organization developed their level of competency, how autonomous they felt, how content they were, and how the volunteer organization influenced their identity and sense of belonging.

Data Analysis Approach

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the demographic data. Demographic data were examined in terms of frequency, mean, median and central tendency and variability (Portney and Watkins 2009). Descriptive statistics were also used on the data generated from the Likert responses to examine frequency, trend and pattern of responses. Qualitative interview responses were organized using thematic anlysis (Guest et al. 2012). Statements of relevance were highlighted and selected to formulate emerging themes (Van Manen 1990). Trustworthiness and rigor were ensured by cross analysis of the data by the research team (Krefting 1991). The researchers carried out an independent analysis and then came together to reach mutually agreed positions on interpretation on agreed themes. Data from telephone and online surveys were first analyzed separately due to the potential influence of data collection methods on the results. Comparisons between telephone and online surveys revealed that results were comparable across data collection methods; therefore, data were compiled and analyzed across both telephone and online data collection methods.

Results

Likert-scale data examining how the organization contributed to respondent’s sense of belonging, competence, contentment, identity and autonomy are displayed in Table 2.

Analysis of the open-ended questions revealed five major themes regarding why respondents both joined and left the volunteer organization. Relevant quotes from respondents are included in the themes of the findings to emphasize and highlight the particular point being discussed.

Work Overload and Burnout

While respondents often expressed how much pleasure and contentment they gained from their overall experience of the volunteer organization (Table 2), further exploration of responses pointed to a few specific factors that may have impacted members’ sense of contentment and pleasure and may have contributed to their decision to leave the organization. One such commonly occurring factor was perceived work overload and burnout.

Some respondents suggested that membership brought with it a heavy workload that eventually took a toll on them:

I gave 20 years of my life, I enjoyed it but I had enough. It was demanding work, not an easy job…A lot of work outside hours…Eventually you burn out. (Respondent 50).

In some cases, respondents also indicated that they believed there was an uneven distribution in member workload and variability in members’ willingness to complete tasks, such that those who took on more of the work would become disillusioned and dissatisfied:

The lack of volunteers to do things in the community…too many people wanting to say what needed to be done but not enough do-ers, not enough follow-through (Respondent 55).

Lack of Autonomy and Voice

Respondents made frequent mention of the broader hierarchy of the club as determinants of their experience of the organization, and of the way working relationships developed between members.

Respondents’ perceptions of club and region structures also appeared to have a significant impact on an individuals’ sense of autonomy, power and voice within organizational structures.

Most respondents appeared to acknowledge that while specific hierarchies existed, and were necessary, some respondents saw these hierarchies as restricting. Several respondents were particularly critical of perceived power differentials within the organization that left them feeling frustrated. For example, they reported difficulties for general members to initiate preferred projects without approval of the Club Board:

I would get mixed feedback on what I could or couldn’t do. Everything had to go through the Board…too slow to get an answer (Respondent 55).

Overall, respondents appeared to agree that their capacity and power to make decisions increased as they became more involved in leadership roles:

As a member, you wouldn’t get as much (autonomy) because the Board gives the final say. As you become a Director or a President you get more influence. If there is a financial implication… then the Board will examine further and if it’s a fair bit of money then it was less likely to be given approval. (Respondent 49).

Despite the apparent increase in power brought on by club leadership positions, some respondents alluded to increased pressure from further up the organization hierarchy and felt restricted in their dealings between their local club and the region:

I wasn’t a big fan of the region conferences and all that. I didn’t like it when I was President and region officials coming to observe me, watch over me, I didn’t really like that. I didn’t like having to go to region meetings. You are expected to go when you are President. (Respondent 49).

Within our club I had complete autonomy but within the worldwide organization I probably still had to stick to protocols. (Respondent 57).

Despite these power differentials, most respondents reported enjoying a high level of autonomy and freedom to make their own decisions and to complete tasks within their role and the parameters established by their Board or region Executive. Of note, one respondent noted much less freedom in the organization when compared to other areas of their life:

You don’t have autonomy… you can’t do your own thing. You have to lead, inspire but there is hierarchy. In my own life I owned a business and could do whatever I wanted but not at [the organization]. (Participant 65).

Other respondents expressed frustration at not being able to engage fully in their duties club. Some respondents argued that they would have been more involved in the club, had they had the same financial means as other members:

Financially was a struggle and in the end didn’t think it was worth it e.g. pay membership, dinner, parking, donations - I don’t think some [volunteers] understand that some people need to be careful with their money and can’t contribute like other members can. (Respondent 62).

Alienation and Cliques

Respondents to both telephone and online survey indicated a sense of belonging and fellowship as a result of engagement in the volunteer organization, with a number of respondents reporting that a desire for a place to belong underpinned their initial motivation to join the organization.

For my husband and I to engage in a volunteer activity together, working with the community and other like-minded people and for fellowship and fun. (Respondent 53).

Similarly, respondents also reported joining the organization as a means of developing social connections and friendship. Respondents reflected that the organization offered opportunity for social interaction and the opportunity to meet other people and spend time away from family:

Camaraderie and networking with a nice bunch of people. (Respondent 2).

Contrary to this sense of belonging, the findings appear to point to a majority of respondents feeling cynical and disenfranchised.

Of the 64 people who completed the question, over 63% of respondents indicated lower than average levels of belongingness. Respondents identified several barriers to belonging and its impact on member retention, citing factors including ‘club cliques,’ and alienation. One respondent described feeling disconnected from other club members:

Some of the guys who had been there a while, they thought they owned the club. Personality clashes; time new people came and I started to not feel like a member anymore. A lot of them that came in were all friends. Many of the older members felt they were not seen the same by the younger members. (Respondent 63).

This sense of disconnect with the club was identified by another respondent:

I felt that the particular club was unfriendly and I felt that I had to prove myself rather than join in the way I had anticipated. There were definite cliques (Respondent 5).

While the social structure of the clubs appeared to play a significant role in feelings of belongingness, some members reported that a sense of hierarchy based on the member’s financial status contributed to feelings of alienation, which appeared to drive resignation from the organization:

The club I belonged to also had quite high status and wealthy members and I found this alienating at times as a young middle-class adult who had not stemmed from a privileged background and was still trying to find their way in life. I found the focus of the club to be inauthentic at times and lacking any real sense of integrity. (Respondent 6).

Of note, the length of membership was perceived as a barrier to facilitating a club sense of belonging. Several respondents commented that as they grew older with their fellow volunteers, they subsequently lost numbers of enthusiastic members, impacting on their ability to relate to new members. The loss of members appeared to the detriment of the club’s ability to function. Similarly, there was a feeling that new members joined for reasons perceived to be inconsistent with their own motivations, such as making business connections. For these individuals, there appeared to be disconnect between the original reason respondents joined and the reality of being a volunteer within the organization.

I think a lot of members that left came in for wrong idea i.e. to gain business but members now are not businessmen anymore so need to change focus to community. (Respondent 57).

However, respondents also expressed the need for time and space to develop a sense of belonging for new members:

Even though I didn’t always feel comfortable, by the end I had a core group of [volunteers] who I caught up with regularly and knew well. It took some time but by the end I felt very much that I fit in. (Respondent 6).

Disconnect between Volunteer and Organization

Disconnect between the volunteers’ motivations for joining the organization and the reality of involvement in the club appeared to influence satisfaction with the organization.

In particular, some respondents felt disillusioned when their Board took a purely financial approach to projects rather than considering the members’ areas of interest and particular skills as well as the potential benefits to the community.

Respondents also held mixed views of the organization protocols and policies. Some respondents lamented the erosion of past customs and the disappearance of club traditions and believed these changes negatively impacted their enjoyment of club activities:

There were a lot of protocols but that started to disappear, things that used to make me feel happy (e.g. the fines sessions). (Respondent 63).

[Club] meetings should be fun. I found one club was fun and efficient, and stuck to protocol but another club was not running as efficiently, not run with protocol. If it’s run to protocol you get the business done quickly and get to have fun afterwards. (Respondent 53).

On the other hand, several respondents reported that they had not enjoyed their club’s inflexible application of various policies and protocols such as attendance requirements, meal costs, expected financial contributions or timing of meetings. Several respondents indicated that they had little spare time or financial capacity to engage to the club requirements or expectations, while some perceived club protocols as more suitable to retirees who may have sufficient time and financial resources to attend than younger members engaged in full-time employment:

Expectation to attend regular meetings became tedious – the new president warned I would need to attend more meetings, but I can’t (I have very little spare time). I was a little jaded by membership drives and requirements on attendance. I know why the requirement is there but it should be about what you contribute not how often you attend. There seemed to be too much attention on attendance and no other aspects of membership. (Respondent 58).

Respondents also expressed varied opinions about the evolution of the organizations values and traditions. For example, some respondents stated that the organization had traditionally been a ‘male-only’ organization and that recent changes to open membership to female members had negatively impacted their enjoyment of club activities:

I felt like the club was going wrong – women were joining the club and felt like they were taking over. They managed to get themselves on the Board and were going in a different direction. (Respondent 63).

Respondents stated that they did not feel their club had sufficiently modernized and evolved and believed that many of the club traditions were now outdated. Several respondents indicated that they would only consider rejoining on the condition that their club changed its practices. Again, several participants alluded to a gender issue:

Strong element of right wing misogynistic club members who were happy for women to do the minute keeping, newsletter writing and organizing but were definitely not interested in their voice. The misogyny, in spite of every effort being made to encompass diversity [in the club], at the grass roots level it is still a boy’s club. (Respondent 9).

Responses also suggested a divide between how older and younger generations perceived the evolution of club traditions. Several older, long-term members disapproved of the loss of traditions; however, for many younger members, the club culture was too outdated and was not attractive to them:

I found some of the rituals absurd. The format was out of the 70s. (Respondent 5).

While there was disconnect between the volunteers ceasing their engagement in the organization and the organization itself, disconnect was also apparent between respondents’ and other members of the organization:

I felt the target demographic was predominantly retired people with a huge amount of free time and lifestyle flexibility, the average age of the members of the club I was involved in was probably 60. (Respondent 16).

Some participants suggested that the organization needed to become more relevant to younger people in order to attract and retain members:

I think [the organization] need to find out what the young people want. You still have 60+ people trying to attract young people but they’re not sure how, they are still doing the same things to attract them. [The organization] needs to work out what they want, what kind of club they want to be. (Respondent 50).

Lack of Faith in Leadership

A deeper issue of trust, particularly as it related to working relationships and leadership, also emerged. Respondents commented on a perceived lack of trust in their club’s leadership in instances when poor member behavior was not addressed appropriately:

I didn’t think the President was strong enough at the time. That’s the problem with [the organization] - you need to rotate President but not all members are leaders. (Respondent 54).

Respondents also indicated that in some cases, their independent efforts were not recognized or valued by other members and particularly by those in leadership positions, placing them at odds with their club. One respondent identified a perceived lack of support from their club after they experienced barriers to a project they were running, as a reason for leaving:

I was assigned to advertise [the organization] and put street signs up… but change of venue and another [organization] clubs moved into venue and took over event (without doing all the work). When I brought it up with my club, they told me to get over it - I felt let down. (Respondent 65).

Respondents reported that they did not feel supported by the regions or the head office and office bearers:

Support for head office was only in terms of workshops, not hand-on…office bearers who would come up with ideas that weren’t interesting to me. They were good ideas that would help people, but I didn’t think they were projects I found valuable. They were not of interest to me, to the office bearers’ yes but not to me. (Respondent 47).

Discussion

The evaluation of why volunteer members join and leave organizations contributes to a unique insight into the experiences of volunteers and the implications for future strategies for the growth and healthy development of volunteer organizations and its members. Areas of need identified by the respondents include the themes of Work overload and burnout,’ ‘Lack of autonomy and voice,’ ‘Alienation and cliques,’ ‘Disconnect between volunteer and organization’ and ‘Lack of faith in leadership.’

It has been argued that belonging is key to a sense of well-being (Whalley Hammell and Iwama 2012). A good proportion of respondents identified their main purpose of joining the organization was for a place to belong and connect with others. Yet despite stating these reasons, respondents indicated low levels of belonging. Citing factors included club cliques, inauthenticity of club ideals, retirement of founding members, paternalistic and misogynistic attitudes and behaviors. These findings are largely consistent with previous studies examining volunteer retention which have found that feelings of social inclusion influence volunteer retention (Waters and Bortree 2012). Efforts by volunteer organizations to ensure that members feel socially included may assist in improving retention rates.

Related to this feeling of belonging, respondents also felt a sense of inequality within the context of financial or social status. Individually these factors are of concern, given the impact they appear to be having on retention of members. Similarly, there appears to be disconnect between incoming ‘new members’ and ‘old’ existing members. Previous research has indicated that the ‘fit’ between the volunteer and the organization may be a greater indicator of volunteer satisfaction and retention than the club culture (Van Vianen et al. 2008). It is possible that new members entering the club perceive a mismatch between their values, motives and beliefs, and those of existing members of the organization, with this perhaps compounded by a perceived disconnected between their social and financial status and other members. Given that the club examined is deeply embedded in tradition and has historically appealed largely to older individuals, it is possible that the values held by the clubs’ members do not hold well according to contemporary societal values and ideas, contributing to issues in retaining younger individuals or those holding differing values. A potential suggestion to managing the reported feelings of ‘cliques’ includes pairing new members with club mentors to assist in reducing feelings of alienation and cliqueness within clubs.

Models of volunteer retention have identified three key phases of volunteering: novice, episodic and sustained (Hyde et al. 2016). A feeling of social connectedness and belonging is essential for retaining novice volunteers and provides the foundation for volunteers to transition from novice to sustained members of an organization. While a commitment to the organization and a motivation to support the volunteer organization financially may assist in the retention longer-term volunteers, this may not be the case for newer members (Hyde et al. 2016). It is possible that the policies and procedures currently in place do not provide adequate support to integrate new members into the club and to assist them to transition from novice to longer-term members.

The evaluation findings identified that the majority of respondents reported their experience of being a member was characterized by feelings of pleasure and contentment. Doble and Caron-Santha (2008) define pleasure as the opportunity to engage in enjoyable or fun experiences. Within this context, specific barriers were identified that appeared to lessen their overall sense of enjoyment. These factors included heavy workloads as a volunteer and uneven distributions of workload within clubs. Importantly, respondents identified that the values, protocols and policies of the clubs negatively impact on their enjoyment and subsequently influence their decision to leave the organization. Respondents described how there appeared to be ‘outdated’ practices that negatively impacted on their well-being. Hankinson and Rochester (2005) suggested that outdated practices and attitudes have a major role on volunteer membership and retention. Respondents identified an area of need included the recruitment of younger members that would help challenge some of the older traditions and policies. Similarly, existing members may need to feel empowered to facilitate innovation and change within volunteer organizations. The adoption of progressive values within clubs may be facilitated through the use of open forums supported by the region boards. It is important to note that the cultures and traditions of an organization can also play a role in the retention of volunteers and can contribute to greater engagement of volunteers (Curran et al. 2016). While volunteer organizations may benefit from the adoption of more progressive values and the implementation of modified traditions and policies, it is also essential to retain the brand heritage of associated with the broader volunteer organization.

It is apparent that members have an expectation of region leadership/board/activity that is not being fulfilled. These unfilled expectations have similarly been found to influence volunteer retention previously (Walker et al. 2016). Volunteers and organizations both have an understanding of their respective roles, with these understandings and expectations often not made explicit (Walker et al. 2016). Volunteer organizations may therefore be at risk of volunteers ceasing their engagement if they do not work to ensure a match between the expectations of the volunteer and the organizations. Volunteer and not-for-profit organizations need to ensure that the expectations, roles and responsibilities within the organization are transparent including communication between levels of the organization.

A broader issue of communication emerged from the respondents indicating that the organization’s communication style and strategy were not at a level to meet members’ needs. It was evident that respondents had a range of views regarding how communication should be conducted across various levels within the organization. Some of these views may not necessarily reflect what is current or desired for practice. This is emerging an area that the organization should pay further attention to given the impact that incorrect perception may have on membership retention.

Previous studies have identified that voice, or the perception of being recognized and heard, has the capacity to influence volunteer retention (Garner and Garner 2011). In the current study, the idea of working relationships, hierarchy, autonomy and trust were raised, perhaps corroborating and extending upon these theories related to organization voice. Autonomy is strongly related to perceptions of agency. Doble and Caron-Santha (2008) propose that individuals’ need for agency is addressed when they perceive that they exert influence or control in important or valued aspects of their occupational lives. Agency may be experienced when individuals choose what occupations they do, and how, when, where, how often, and with whom they perform occupations. A major consideration identified by the respondents included the clubs investing time and effort on new member support, for example, by ensuring adequate mentoring of incoming members, and by exploring and establishing projects aimed at new members’ particular interests and skills. Similarly reviewing club manual, protocols, culture and practice, e.g., transparent process for nomination of its leaders, may be beneficial.

A number of limitations are associated with the current study. Firstly, this study examined the perceptions of former volunteers from one region; it is possible that the views expressed by those in the current study do not generalize to other regions or clubs, or other volunteer and not-for-profit organizations (Polit and Beck 2010). Indeed, the unique nature of the individual clubs was highlighted by the respondents in the current study. The limited sample size is also acknowledged (Sandelowski 1995). While attempts were made to contact all former volunteers of the region, only a small number of former volunteers from this pool participated in the study. The nature of the sample may have also contributed to a bias in the results (Collier and Mahoney 1996); it is possible those who participated felt higher levels of dissatisfaction. Due to the broad geographic locations of participants, telephone interviews were used in place of traditional face-to-face interview methods. Telephone interviews have drawn criticism due to the reduction in visual, contextual and nonverbal cues available to the interviewer, possibly influencing their interpretation of the interview content (Novik 2008). However, this potential influence was reduced through the use of member-checking with the interviewees, and it is possible that the format of interviews contributed to the interviewee providing more sensitive responses (Novik 2008). Finally, it is also possible that the results may have been influenced by the interpretation of the results by the researchers; attempts to address these potential concerns were made by the researchers with cross-checking of the data conducted by the research team (Mays and Pope 1995).

In conclusion, the research findings have shown that its members value and enjoy participation in the organization and value its guiding principles. However, factors including communication, club culture and practices, feelings of belonging and autonomy influenced respondent’s decisions to cease their engagement with the organization. Volunteer organizations should seek to refine and improve their practices and culture, with a focus on facilitating communication within clubs, with an emphasis on the integration of new members to foster a sense of belonging. Further refinement and improvement of organization practice and culture may strengthen the organization position and membership numbers.

References

Cattan, M., Hogg, E., & Hardill, I. (2011). Improving quality of life in ageing populations: What can volunteering do? Maturitas, 70(4), 328–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.08.010.

Chen, L.-K. (2016). Benefits and dynamics of learning gained through volunteering: A qualitative exploration guided by seniors’ self-defined successful aging. Educational Gerontology, 42(3), 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2015.1108150.

Collier, D., & Mahoney, J. (1996). Insights and pitfalls: Selection bias in qualitative research. World Politics, 49, 56–91. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.1996.0023.

Coolican, H. (2014). Research methods and statistics in psychology (6th ed.). Hove, East Sussex: Psychology Press.

Curran, R., Taheri, B., & O’Gorman, K. (2016). Nonprofit brand heritage its ability to influence volunteer retention, engagement and satisfaction. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(6), 1234–1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764016633532.

Doble, S., & Caron-Santha, J. (2008). Occupational well-being: Rethinking occupational therapy outcomes. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(3), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740807500310.

Etikan, I., Musa, S., & Alkassim, R. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11.

Garner, J. T., & Garner, L. T. (2011). Volunteering an opinion: Organizational voice and volunteer retention in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(5), 813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764010366181.

Greenfield, E., & Marks, N. (2004). Formal volunteering as a protective factors for older adults’ psychological well-being. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 59(5), S258–S264. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.5.S258.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K., & Namey, E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Hankinson, P., & Rochester, C. (2005). The face and voice of volunteering: A suitable case for branding? International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 10, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.15.

Harp, E. R., Scherer, L. L., & Allen, J. A. (2017). Volunteer engagement and retention. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(2), 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764016651335.

Hyde, M. K., Dunn, J., Bax, C., & Chambers, S. K. (2016). Episodic volunteering and retention: An integrated theoretical approach. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764014558934.

Kim, M., Chelladurai, P., & Trail, G. T. (2007). A model of volunteer retention in youth sport. Journal of Sport Management, 21(2), 151–171. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.21.2.151.

Krefting, L. (1991). Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(3), 214–222. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.45.3.214.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (1995). Rigour and qualitative research. British Medical Journal, 311(6997), 109–112.

Musselwhite, K., Cuff, L., McGregor, L., & King, K. (2006). The telephone interview is an effective method of data collection in clinical nursing: A discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(6), 1064–1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.05.014.

Newton, C., Becker, K., & Bell, S. (2014). Learning and development opportunities as a tool for the retention of volunteers: A motivational perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(4), 514. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12040.

Novik, G. (2008). Is there a bias against telephone interviews in qualitative research? Research in Nursing & Health, 31(4), 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20259.

Polit, D., & Beck, C. (2010). Generalization in quantitive and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47, 1451–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004.

Portney, L., & Watkins, M. (2009). Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Qualtrics. (2017). Qualtrics. Retrieved from http://www.qualtrics.com. Accessed 4 Nov 2016.

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(2), 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770180211.

Terrell, S. (2012). Mixed-methods research methodologies. Qualitative Report, 17, 254–280.

Van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. New York: State University of New York Press.

Van Vianen, A. E. M., Nijstad, B. A., & Voskuijl, O. F. (2008). A Person-environment fit approach to volunteerism: Volunteer personality fit and culture fit as predictors of affective outcomes. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 30(2), 153.

Veludo-de-Oliveira, T. M., Pallister, J. G., & Foxall, G. R. (2015). Unselfish? Understanding the role of altruism, empathy, and beliefs in volunteering commitment. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 27(4), 373. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2015.1080504.

Volunteering WA. (2015). Economic, social and cultural value of volunteering to Western Australia. Perth: Volunteering WA.

Walker, A., Accadia, R., & Costa, B. M. (2016). Volunteer retention: The importance of organisational support an psychological contract breach. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(8), 1059. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21827.

Warburton, J. (2010). Volunteering as a productive ageing activity: Evidence from Australia. China Journal of Social Work, 3(2–3), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17525098.2010.492655.

Warburton, J., Paynter, J., & Petriwskyj, A. (2007). Volunteering as a productive aging activity: Incentives and barriers to volunteering by Australian seniors. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 26(4), 333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464807304568.

Waters, R. D., & Bortree, D. S. (2012). Improving volunteer retention efforts in public library systems: How communication and inclusion impact female and male volunteers differently. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 17(2), 92. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.438.

Whalley Hammell, K., & Iwama, M. (2012). Well-being and occupational rights: An imperative for critical occupational therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 19(5), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2011.611821.

Wilson, A. (2012). Supporting family volunteers to increase retention and recruitment. ISRN Public Health, 2012. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/698756.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Richard Pascal for his support in data collection and data analysis. The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to Rotary Australia for allowing this study to take place.

Funding

This research and evaluation were funded by Rotary Intentional. The authors report no financial interest or benefit arising from direct application of the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Professor Buchanan makes declaration of role as a past Rotary District Governor.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Milbourn, B., Black, M.H. & Buchanan, A. Why People Leave Community Service Organizations: A Mixed Methods Study. Voluntas 30, 272–281 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-0005-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-0005-z