Abstract

Real-world evidence focusing on medication switching patterns amongst direct oral anticoagulant (DOACs) has not been well studied. The objective of this study is to evaluate patterns of prescription switching in non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients initiated on a DOAC and previously naïve to anticoagulation (AC) therapy. Data was obtained from Truven Health MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental database (2009–2013). AC naïve (those without prior anticoagulant use) NVAF patients initiated on a DOAC, with 6 months of continuous health plan enrollment before and after treatment initiation and maintained on continuous therapy for a minimum of 6 months were included. Of 34,022 AC naïve NVAF patients initiating a DOAC, 6613 (19.4%) patients switched from an index DOAC prescription to an alternate anticoagulant and 27,409 (80.6%) remained on the DOAC [age: 68.5 ± 11.7 vs. 67.1 ± 12.7 years, p < 0.001; males: 3781 (57.2%) vs. 17,160 (62.6%), p < 0.001]. Amongst those that switched medication, 3196 (48.3%) did so within the first 6 months of therapy. Overall, 2945 (44.5%) patients switched to warfarin, 2912 (44.0%) switched to another DOAC and 756 (11.4%) switched to an injectable anticoagulant. The highest proportion of patients switched from dabigatran to warfarin (N = 2320; 42.5%) or rivaroxaban (N = 2252; 41.3%). The median time to switch from the index DOAC to another DOAC was 309.5 days versus 118.0 days (p < 0.001) to switch to warfarin. In NVAF patients newly initiated on DOAC therapy, one in five patients switch to an alternate anticoagulant and one of every two patients do so within the first 6 months of therapy. Switching from an initial DOAC prescription to traditional anticoagulants occurs as frequently as switching to an alternate DOAC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

After many decades of warfarin use, the antithrombotic landscape now includes four direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) approved for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients. Each DOAC agent (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban) was demonstrated to be at least as safe and effective as warfarin [1,2,3,4]. DOACs also offer increased conveniences to patients and providers alike, such as predictable dose response, the elimination of routine laboratory monitoring, as well as less drug–food and drug–drug interactions [5, 6]. Given these advantages, perhaps it comes as no surprise that utilization of DOACs has increased worldwide [7,8,9,10,11], and as many as half of the patients treated with oral anticoagulants in Europe and North America are now treated with a DOAC [12].

While utilization trends have been documented, real-world evidence focusing on treatment switching patterns amongst DOACs is not well studied. Currently, the majority of the literature focuses on medication safety once anticoagulant therapy has been switched [13,14,15,16] or on attitudes to switching therapy [17, 18]. While recent studies have assessed switching patterns in warfarin initiators [19] or in a mixed anticoagulation (AC) therapy naïve and non-naïve cohort [20], there remains a paucity of literature examining switching patterns amongst those initiating a DOAC and from DOACs to traditional therapies. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate patterns of prescription switching in NVAF patients initiated on a DOAC and previously naïve to AC therapy.

Methods

Setting and participants

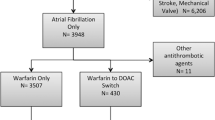

This is a retrospective observational cohort study using patient-level claims data to evaluate patterns of medication switching amongst NVAF patients initiating a DOAC. Data was obtained from Truven Health MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Database for the period 01/01/2009–12/31/2013. This database contains de-identified medical claims for over 200 million unique U.S. patients. The database is comprised of patient-level medical inpatient and outpatient claims, enrollment, and outpatient prescription information [21, 22]. Anticoagulant prescription use was determined by National Drug Codes (NDC) in the outpatient prescription file.

Patients were selected into the study cohort by the following inclusion criteria: (1) ≥ 1 prescription for a DOAC; (2) ≥ 18 years of age at the date of the first DOAC prescription (hereafter referred to as the ‘index date’); (3) first NVAF diagnosis prior to index date was confirmed with either 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient International Classification of Diseases ninth edition (ICD-9) codes for AF (ICD-9: 427.31) in the primary or secondary diagnosis position; (4) having at least 6 months of continuous health plan enrollment before and after index date. Patients were excluded from the study cohort if they had any previous use of an anticoagulant prior to index date or a concurrent claim for warfarin or another DOAC on the index date.

Outcomes

Several outcomes were measured following DOAC initiation. First, medication usage patterns of any DOAC (dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban) was observed. Edoxaban was not included as it was not yet available and FDA approved during the study period. Secondly, medication switching patterns among patients newly initiated on a DOAC were assessed. A medication switch was defined as a claim during the follow-up period for an anticoagulant different than the index DOAC medication. This was evaluated by (1) counting the number of switches from the index DOAC medication, (2) documenting the first alternate anticoagulant the patient was switched to from the index DOAC, and (3) the time in days to switch from the first anticoagulant to the alternate anticoagulant. Lastly, predictors of switching from the index DOAC therapy to alternate anticoagulants were examined.

Baseline covariates

Patient demographic characteristics were identified at index date. These characteristics include: age, gender, type of health plan [comprehensive, exclusive provider organization (EPO), health maintenance organization (HMO), point-of-service (POS), preferred provider organization (PPO), high-deductible health plan (HDHP) and consumer-driven health plan (CDHP)] and census region of residence (northeast, north central, south, west and unknown). Clinical characteristics such as comorbidities were identified in the 6-month period prior to index date. As such, comorbidities and an aggregate Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was generated using previously validated ICD-9 algorithm using inpatient and outpatient medical claims [23].

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between patients who switched from their index DOAC and those who remained on their index DOAC. Student t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum test, as appropriate, were used to compare continuous variables and the Chi square test was used to compare categorical variables. A subgroup analysis of switching patterns by age group (< 55, 55–64, 65–74, and ≥ 75 years) was conducted by using the Chi square test. The time to switch to the first alternate anticoagulant was assessed by using a Median Two-Sample Wilcoxon rank sum test. Factors associated with switching from the index DOAC to alternate anticoagulants were examined by multivariate logistic regression. Covariates from Table 1 (with p < 0.2 in univariate logistic models) were entered into a final multivariate model using a backward elimination process that only retained covariates with p < 0.05. The University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB) provided a determination that this work was not deemed human subjects research (#2016-0043).

Results

A total of 34,022 NVAF patients were included in the study cohort, with 1 in 5 patients switching from their index DOAC to an alternate anticoagulant. More specifically, 6613 (19.4%) patients switched therapy while 27,409 (80.6%) remained on their index DOAC (Table 1). The mean age [± standard deviation (SD)] between those patients that switched and those that remained on the index DOAC was 68.1 ± 11.8 versus 66.7 ± 12.8 years (p < 0.0001), with the highest proportion of patients aged ≥ 75 years [(N = 2215; 33.5%) vs. (N = 8396; 30.6%), p < 0.0001]. The proportion of males was lower in patients that switched therapy compared to those who did not switch [(N = 3781; 57.2%) vs. (N = 17,160; 62.6%); p < 0.0001]. Among those that switched and remained on index DOAC therapy, dabigatran was the most commonly used DOAC in both groups.

Amongst those that switched to an alternate anticoagulant, 29.1% (N = 1942) of patients switched therapy once during follow-up and 70.9% (N = 4689) switched ≥ 2 times (Table 2). Patients that switched therapy primarily switched to warfarin (N = 2945; 44.5%) or another DOAC (2912; 44.0%). Observing switching rates by individual DOACs, 23.2% (N = 5456) of patients switched from dabigatran, 11.2% (N = 1110) from rivaroxaban and 7.5% (N = 47) from apixaban. The majority of patients switched from dabigatran to rivaroxaban (N = 2252; 41.3%) or to warfarin (N = 2320; 42.5%) as their first alternate anticoagulant.

In assessment of switching patterns by time, the overall median (interquartile range; IQR) time to first switch from index date was 190.0 (63.0–420.0) days. More specifically, the duration of time to switch to warfarin was 118.0 (41.0–287.0) days and to an alternate DOAC was 309.5 (119.0–552.0) days (Table 3). Additionally, within 6 months of DOAC therapy initiation, 1 in 2 patients had switched to an alternate anticoagulant (48.3%) (Fig. 1a). The percentage of patients that switched their index DOAC continued to increase gradually over time. Examining switching patterns over time, compared to DOACs, a higher proportion of patients switched to warfarin at each time point (between 6 and 24 months post index date) (Fig. 1b).

In terms of switching patterns across age groups, a greater proportion of older adults (≥ 65 years) switched their initial DOAC therapy when compared to those < 65 years old (Table 4). Further, 21.5% (N = 1681) of patients 65–74 years and 20.9% (N = 2215) of patients ≥ 75 years switched to an alternate anticoagulant. Amongst patients ≥ 75 years, 49.9% switched to warfarin and 43.2% to an alternate DOAC.

All baseline covariates presented in Table 1 were included in a multivariate model to determine predictors of switching initial DOAC therapy. Region was not included in the model as it was not associated with switching therapy in univariate analysis (p > 0.2). In addition, each variable included in the health plan covariate was also removed from the multivariate analysis due to p > 0.05. Therefore, the predictors of switching index DOAC therapy were age, sex, CCI and the type of index medication (Table 5). Each age group (55–64, 65–74 and ≥ 75 years) significantly increased the odds of switching initial therapy by 15–40% compared to < 55 year olds. Compared to females, being a male decreased the odds of switching therapy by 18% (OR 0.82; CI 0.78–0.87; p < 0.0001). Interestingly, using apixaban or rivaroxaban as the index DOAC significantly decreased the odds of switching therapy by 75 and 59%, respectively, compared to dabigatran [(apixaban: OR 0.25; CI 0.18–0.34; p < 0.0001); (rivaroxaban: OR 0.41; CI 0.38–0.44; p < 0.0001)].

In an effort to explore additional factors that may influence switching patterns among DOAC initiators, additional analysis was undertaken. Factors that were examined included mean copayments (copays), the timing of FDA approvals for rivaroxaban and apixaban, renal function and clinical outcomes. With regard to mean copays, there was no statistically significant difference in the mean copays between patients that switched index DOAC and those that did not [(switched index DOAC: $45.07) vs. (remained on index DOAC: $45.48); p = 0.46]. Further, only 4.4% (N = 100) and 6.9% (N = 33) of patients switched their index DOAC therapy within 3 months of rivaroxaban and apixaban approval, respectively., Among all adults that switched index therapy, only 5.7% (N = 378) had renal insufficiency. Lastly, the proportion of patients experiencing a thromboembolic or bleeding event decreased after switching therapy. Among adults that switched therapy, 198 (3.0%) experienced a stroke/TIA event prior to switching but only 69 (1.0%) patients had an event after switching therapy (p < 0.0001). Similarly, 136 (2.1%) patients experienced a major bleed prior to switching but 115 (1.7%) had an event after switching therapy (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

In our study of AC naïve NVAF patients, 19.4% switched from their index DOAC therapy to an alternate anticoagulant. Of those that switched, interestingly, similar proportions of patients switched to either a different DOAC (44.0%) or to warfarin (44.5%). Further, almost 71% of patients had ≥ 2 switches in their anticoagulant therapy. While the highest proportion of patients initiated dabigatran, this should not necessarily be construed as provider preference but rather as specific DOACs availability in the US and the timeframe of our dataset. Given this, however, it is important to note that almost 1 in 4 dabigatran initiators switched their therapy to either rivaroxaban (41.3%) or to warfarin (42.5%). The decrease in dabigatran utilization over time is consistent with findings also reported in previous studies [9, 19, 24].

The DOACs have been considered to be more convenient and at least as safe and effective as warfarin, yet in this real-world study we see a large percentage of our cohort switching over to warfarin. More specifically, nearly 50% of adults ≥ 75 years old switched from their index DOAC to warfarin and in the majority of cases this switch occurs within the first few months of DOAC initiation. Interestingly, as only 8.8% of these adults (≥ 75 years old) had documented renal insufficiency, additional clinical and patient related factors likely contribute to the preference for warfarin over a DOAC. One such factor could be the preference and benefits of a more structured anticoagulation management approach that offers patients a greater provider support system and enhanced education.

Given that a fairly high percentage of patients switched from their index DOAC and this aspect has not been previously studied amongst DOAC initiators, we explored factors that may explain the necessity to switch. Our multivariate model illustrated that older age and female gender were significantly associated with a higher likelihood to switch index therapy. Additionally, since one of the core criticisms against DOAC use has been their high cost, we compared the mean copays for the index DOAC prescription between patients that switched and those that remained on their index medication. Since there was no statistically significant difference in the mean copays for the two groups, it remains inconclusive if economic circumstances alone drive switching behavior. Additionally, we examined whether FDA approval had an impact on switching patterns. To this end, only a small percentage of patients switched their therapy within 3 months of rivaroxaban and apixaban approval, thereby reducing any reasoning that the availability of newer DOACs motivated switching behavior. Furthermore, we specifically observed renal function in this cohort in order to assess whether renal insufficiency may impact switching patterns. Again only a small proportion of patients that switched had renal insufficiency. Lastly, in assessment of thromboembolic and bleeding outcomes, it is observed that the proportion of patients experiencing an event significantly decreases after the switching of therapy. Perhaps then, clinical outcomes act as the catalyst for switching from an index DOAC to an alternate anticoagulant because all other factors provide inconclusive evidence. Given this, further investigation is warranted to assess clinical and patient related factors such as therapy related complications, drug interactions or patient and provider preferences for systematic management models of care.

While our study addresses a knowledge gap in current, contemporary anticoagulation practice, our results must be interpreted in context of some study limitations. Given the nature of administrative claims data, there are potential covariates that may predict or explain switching behavior, yet were not available in the dataset such as demographic, socioeconomic or clinical factors. Especially in the case of disease states such as renal insufficiency, laboratory values were not available in our dataset, and therefore previously validated algorithms were used [23]. Additionally, specific reasons for switching were not included in this dataset, which are important to this work. However, we have explored factors such as medication cost and FDA approval status to assess their potential impact on switching patterns. Also, as patients were required to meet continuous enrollment criteria, those that had dis-enrolled or died were not eligible to contribute to our cohort. Lastly, this study uses data from a commercially insured population which may not be generalizable to other populations. Despite these limitations, using administrative claims to address medication usage patterns is a defensible approach [25].

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study is among the first to assess real-world DOAC treatment switching patterns in previously AC naïve patients with NVAF. Among these patients, 1 in 5 switched their initial DOAC to an alternate anticoagulant and 1 in 2 switched their therapy within the first 6 months of initiation. Interestingly, switching from an initial DOAC prescription to traditional anticoagulants occurred just as frequently as switching to an alternate DOAC. While additional investigation is warranted to assess potential causes for switching, the availability of DOAC-specific reversal agents and emergence of personalized medicine will contribute to shaping future antithrombotic treatment patterns.

References

Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S et al (2009) Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 361(12):1139–1151

Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J et al (2011) Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365:883–891

Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ et al (2011) Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365(11):981–992

Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E et al (2013) Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 369:2093–2104

Spyropoulos AC, Goldenberg NA, Kessler CM, Kittelson J, Schulman S, Turpie AG, Cutler NR, Hiatt WR, Halperin JL, The Antithrombotic Trials Leadership and Steering Group (2012) comparative effectiveness and safety of the novel oral anticoagulants: do the pivotal clinical trials point to a new paradigm? J Thromb Haemost 10(12):2621–2624

Barnes GD, Ageno W, Ansell J, Kaatz S, Subcommittee on the Control of Anticoagulation of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (2015) Recommendation on the nomenclature for oral anticoagulants: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 13:1154–1156

Elewa H, Alhaddad A, Al-Rawi S et al (2017) Trends in oral anticoagulant use in Qatar: a 5-year experience. J Thromb Thrombolysis 43(3):411–416

Barnes GD, Lucas E, Alexander GC et al (2015) National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med 128:1300–1305

Weitz JI, Semchuk W, Turpie AG, Fisher WD, Kong C, Ciaccia A, Cairns JA (2015) Trends in prescribing oral anticoagulants in Canada, 2008–2014. Clin Ther 37(11):2506–2514.e4

Desai NR, Krumme AA, Schneeweiss S, Shrank WH, Brill G, Pezalla EJ, Spettell CM, Brennan TA, Matlin OS, Avorn J, Choudhry NK (2014) Patterns of initiation of oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation-quality and cost implications. Am J Med 127(11):1075–1082.e1

Olesen JB, Sørensen R, Hansen ML, Lamberts M, Weeke P et al (2015) Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulation agents in anticoagulant naïve atrial fibrillation patients: Danish nationwide descriptive data 2011–2013. Europace 17(2):187–193

Huisman MV, Rothman KJ, Paquette M, Teutsch C, Diener HC et al (2015) Antithrombotic treatment patterns in patients with newly diagnosed nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: the GLORIA-AF Registry, Phase II. Am J Med 128(12):1306–1313

Schiavoni M, Margaglione M, Coluccia A (2017) Use of dabigatran and rivaroxaban in non-valvular atrial fibrillation: one-year follow-up experience in an Italian centre. Blood Transfus 31:1–6

Beyer-Westendorf J, Gelbricht V, Förster K, Ebertz F, Röllig D et al (2014) Safety of switching from vitamin K antagonists to dabigatran or rivaroxaban in daily care–results from the Dresden NOAC registry. Br J Clin Pharmacol 78(4)908–917

Clemens A, van Ryn J, Sennewald R, Yamamura N, Stangier J et al (2012) Switching from enoxaparin to dabigatran etexilate: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety profile. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 68(5):607–616

Bouillon K, Bertrand M, Maura G, Blotière PO, Ricordeau P et al (2015) Risk of bleeding and arterial thromboembolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation either maintained on a vitamin K antagonist or switched to a non-vitamin K-antagonist oral anticoagulant: a retrospective, matched-cohort study. Lancet Haematol 2(4):e150–e159

Auyeung V, Patel JP, Abdou JK, Vadher B, Bonner L et al (2016) Anticoagulated patient’s perception of their illness, their beliefs about the anticoagulant therapy prescribed and the relationship with adherence: impact of novel oral anticoagulant therapy—study protocol for The Switching Study: a prospective cohort study. BMC Hematol 16(1):22

Attaya S, Bornstein T, Ronquillo N, Volgman R, Braun LT et al (2012) Study of warfarin patients investigating attitudes toward therapy change (SWITCH Survey). Am J Ther 19:432–435

Hale ZD, Kong X, Haymart B, Gu X, Kline-Rogers E et al (2017) Prescribing trends of atrial fibrillation patients who switched from warfarin to a direct oral anticoagulant. J Thromb Thrombolysis 43(2):283–288

Hellfritzsch M, Husted SE, Grove EL, Rasmussen L, Poulsen BK et al (2017) Treatment changes among users of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 120(2):187–194

Truven Health Analytics Health research data for the real world: the MarketScan Databases. Available at http://truvenhealth.com/portals/0/assets/PH_11238_0612_TEMP_MarketScan_WP_FINAL.pdf

Truven Health Analytics Truven health analytics links clinical data with claims to enhance oncology outcomes research. Available at http://truvenhealth.com/news-and-events/press-releases/detail/prid/33/Truven-Health-Analytics-Links-Clinical-Data-with-Claims-to-Enhance-Oncology-Outcomes-Research

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie C (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

Adelborg K, Grove EL, Sundbøll J et al (2016) Sixteen-year nationwide trends in antithrombotic drug use in Denmark and its correlation with landmark studies. Heart 102:1883–1889

Grymonpre R, Cheang M, Fraser M, Metge C, Sitar DS (2006) Validity of a prescription claims database to estimate medication adherence in older person. Med Care 44(5):471–477

Acknowledgements

Department of Pharmacy Systems, Outcomes and Policy (PSOP) and the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomic Research (CPR) at University of Illinois at Chicago for providing material support to the research. Dr. Galanter is supported by grant U19HS021093 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Nutescu is supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute Award Number K23HL112908 and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Award Number U54MD010723. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Manzoor, B.S., Walton, S.M., Sharp, L.K. et al. High number of newly initiated direct oral anticoagulant users switch to alternate anticoagulant therapy. J Thromb Thrombolysis 44, 435–441 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-017-1565-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-017-1565-2