Abstract

Direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) agents offer several lifestyle and therapeutic advantages for patients relative to warfarin in the treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF). These alternative agents are increasingly used in the treatment of AF, however the adoption practices, patient profiles, and reasons for switching to a DOAC from warfarin have not been well studied. Through the Michigan Anticoagulation Quality Improvement Initiative, abstracted data from 3873 AF patients, enrolled between 2010 and 2015, were collected on demographics and comorbid conditions, stroke and bleeding risk scores, and reasons for anticoagulant switching. Over the study period, patients who switched from warfarin to a DOAC had similar baseline characteristics, risk scores, and insurance status but differed in baseline CrCl. The most common reasons for switching were patient related ease of use concerns (37.5%) as opposed to clinical reasons (16.5% of patients). Only 13% of patients that switched to a DOAC switched back to warfarin by the end of the study period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

After decades with warfarin as the only anticoagulant for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF), four new direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have become available since 2010. DOACs offer many potential advantages over warfarin including rapid onset of action, no required therapeutic blood level monitoring, less interactions with food and medications, no dosing adjustments, and fewer lifestyle modifications [1–5]. As a result, the clinical use of DOACs has been increasing in the United States and Canada, and accounted for over half of new anticoagulant starts by the end of 2014, and appears to be rising [6–10]. With several anticoagulant options, physicians and patients appear to have an increasingly collaborative role in medication selection [11]. However, the characteristics of the AF patients that switch from warfarin to a DOAC, their reasons for switching, and whether or not they switch back to warfarin, are not well studied.

We hypothesize that warfarin-treated patients with AF who elect to change therapy are younger and with fewer comorbidities as compared to those patients who choose to remain on warfarin. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a retrospective analysis of AF patients from six diverse anticoagulant clinics participating in the Michigan Anticoagulation Quality Improvement Initiative (MAQI2). Additionally, we abstracted data from clinic and hospital visits to monitor for any patients who transitioned from a DOAC back to warfarin.

Methods

Michigan anticoagulation quality improvement initiative (MAQI2)

MAQI2 is a Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network (BCBSM/BCN) quality improvement collaborative [12]. This collaborative of six health system anticoagulation clinics was formed in 2008, with the focus to improve anticoagulation patient safety, healthcare quality, and promoting collaboration on outcomes projects across the state of Michigan. Patients newly enrolling in each center’s anticoagulation clinic are randomly selected for chart abstraction into the MAQI2 database. Trained data abstractors collect de-identified patient care data from anticoagulation clinic visits and supplement that data with both outpatient and hospitalization records. BCBSM/BCN provides funding for data collection and quality improvement work, but does not participate in data analysis or manuscript editing. The MAQI2 project was reviewed and approved by the IRB at the coordinating center (University of Michigan) and each participating site.

Patient selection

Between January 2010 and June 2015, all non-valvular AF patients in the MAQI2 database who were treated with warfarin were eligible for inclusion in this study. Exclusion criteria include patients on anticoagulation solely for indications other than AF (e.g. venous thromboembolism, mechanical valve replacement), patients who switched to non-DOAC warfarin alternatives (e.g. enoxaparin, clopidogrel), and patients with fewer than one follow up encounter. 3873 patients met selection criteria (Fig. 1). These patients were divided into two cohorts: (1) patients who switched from warfarin therapy to DOAC therapy, and (2) patients who remained exclusively on warfarin therapy.

Data collection

Demographic, comorbidity, INR levels, insurance status, and co-administered medication data were collected at the time of enrollment in the anticoagulation clinic. HAS-BLED and CHA2DS2-VASc risk scores, and time in therapeutic range were calculated using the baseline characteristics data to measure patient risk and warfarin INR control [11, 13, 14]. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) status, defined as creatinine clearance (CrCl) <60 mL/min, was obtained from review of the medical record, and laboratory data were used to calculate the estimated CrCl with the Crockroft-Gault equation [15].

Outcomes

The primary outcomes assessed were baseline patient characteristics (age, weight, gender, and presence of CKD). Secondary outcomes include rates and reasons for switching to DOAC, as well as those for switching back to warfarin from a DOAC. Reasons for switching from warfarin to DOAC therapy were abstracted from the medical chart when documented by the physician or anticoagulation clinic provider. These were categorized using pre-defined reasons. Not all patients had a documented reason for switching from warfarin to a DOAC medication.

Statistical analyses

Patient demographics and comorbidities were compared using Fisher’s exact, Cochran-Armitage Trend Tests. A 2-sided test with p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

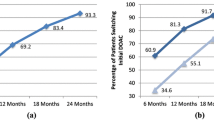

Between 2010 to mid 2015, 400/3873 (10.3%) non-valvular AF patients switched from warfarin therapy to a DOAC. Of the patients who switched to a DOAC, 191 (47.8%) switched to dabigatran, 130 (32.5%) to rivaroxaban, 75 (18.8%) to apixaban, and none to edoxaban. The percent of patient switching from warfarin to dabigatran declined during the study period while the percent of patients switching from warfarin to apixaban increased. Patients who switched to DOAC therapy were less likely to have advanced CKD or to take amiodarone compared to non-switchers. Overall, both groups were similar in baseline characteristics (age, weight, gender), risk scores (HAS-BLED and CHA2DS2-VASc), and insurance status (Table 1).

As shown in Table 2, warfarin treated AF patients more often switched to a DOAC for a patient related ease of use concern (37.5%) than a clinical reason (16.5%). The most common reasons for warfarin to DOAC switching was unstable INR (13.5%), challenges with access to blood drawing laboratories/need for frequent blood draws/need for any dose changes (9.8%), and concerns regarding patient adherence (4.3%).

Of the patients that switch to a DOAC, 52/400 (13%) switch back to warfarin. Roughly half of those patients (28/52, 53.8%) switched from a DOAC back to warfarin within the first 6 months of DOAC use. The most common reasons to switch from a DOAC back to warfarin were side effects (21.2%), clotting events (17.3%), and cost/insurance issues (13.5%) (Table 3).

Discussion

In our study of AF patients initiated on warfarin, 10% changed to DOAC therapy during the period of study. Of those who changed to a DOAC, 10% ended up switching back to warfarin for a variety of reasons. Surprisingly, the baseline characteristics between switchers and non-switchers are relatively similar. In fact, the presence of significant renal dysfunction was the only major difference between the two cohorts. This may be related to patient selection by prescribers given the renal clearance of the DOACs. Additionally, no difference was seen in bleeding and stroke risk or the insurance type. Finally, factors that contribute to patient ease of use and adherence had the greatest impact on the decision to switch from warfarin to a DOAC, accounting for roughly two-thirds (150/216, 69%) of transitions for which data were collected.

Our study is unique as we examined not only the trends in anticoagulant use, but we also explored why the changes occurred. As with other studies of anticoagulant trends, we saw a rise in DOAC utilization during the year each respective DOAC became available, and overtime saw a relative drop in dabigatran use relative to the other DOACs [7, 16]. Also similar to other studies, we found that DOAC patients had better renal function relative to warfarin users, which is reassuring given that severe renal dysfunction is a contraindication for most DOAC medications [17]. However, several studies saw a difference in stroke and bleeding risk among DOAC patients, and others found DOAC users to be younger [6, 17, 18]. We did not find the differences in our population’s risk scores for either bleeding or stroke, which may reflect the contrast between patients who were initially started on warfarin before switching to DOAC therapy (our study) vs. patients who start on DOAC therapy de novo (most other studies).

One other study claimed that patients are playing an increasingly collaborative role in prescribing habits, but that safety concerns, rather than compliance and lifestyle concerns were most important to patients [11]. Our real-world study appears to show rates of bleeding, stroke, and clotting events close to the expected findings of the original data, which is reassuring [1–3].

Our study design has multiple strengths. The study population is an inception cohort of newly initiated warfarin in AF patients, which reduces outside confounders such as prior experience using warfarin or a DOAC, or having failed an alternative treatment prior to the study. Trained abstractors who were familiar with the model of the anticoagulation clinics performed all the data collection and conducted random audits to validate the collected data. These factors ensure high quality retrospective data. The study is based on a unique cohort of patients, those having switched from warfarin to a DOAC, and who have not been well studied prior to this point.

Nevertheless, our study must be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. As it is an observational analysis, there are inherently potential confounders, and reduced generalizability of the study. However, our data registry has a heterogeneous patient population, including patients from rural and urban communities across Michigan. Also, the population covers several health systems, including private, public and academic institutions of various sizes. While the study predominately examined warfarin to DOAC transitions, the data regarding DOAC maintenance and transition back to warfarin may lack generalizability to current DOAC populations (predominately rivaroxaban and apixaban), as the majority of our patients initially switched to dabigatran, the first agent available, yet over the course of our study period, the relative new switches to dabigatran fell as the anti-Xa agents became available [6, 7]. Additionally, there were several patients whose reasons for switching from warfarin to a DOAC were unable to be collected. These unrecorded reasons may have skewed the data.

Conclusions

A significant population of AF patients elect to switch from warfarin to DOAC therapy for stroke prevention. While there are many factors at play in anticoagulant prescribing trends, patient preference factors are likely playing an increasing role. It remains to be seen how the introduction of DOAC-specific reversal agents will impact the clinical decision to remain on warfarin therapy or switch to DOAC therapy for stroke prevention in AF [19, 20].

References

Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener HC, Joyner CD, Wallentin L, RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators (2009) Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 361:1139–1151

Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KA, Califf RM, ROCKET AF Investigators (2011) Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365:883–891

Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A, Bahit MC, Diaz R, Easton JD, Ezekowitz JA, Flaker G, Garcia D, Geraldes M, Gersh BJ, Golitsyn S, Goto S, Hermosillo AG, Hohnloser SH, Horowitz J, Mohan P, Jansky P, Lewis BS, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Verheugt FW, Zhu J, Wallentin L, Aristotle Committees and Investigators (2011) Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365:981–992

Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Halperin JL, Waldo AL, Ezekowitz MD, Weitz JI, Spinar J, Ruzyllo W, Ruda M, Koretsune Y, Betcher J, Shi M, Grip LT, Patel SP, Patel I, Hanyok JJ, Mercuri M, Antman EM, Engage, AF-TIMI 48 Investigators (2013) Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 369:2093–2104

Barnes GD, Ageno W, Ansell J, Kaatz S, Subcommittee on the Control of Anticoagulation of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (2015) Recommendation on the nomenclature for oral anticoagulants: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 13:1154–1156

Desai NR, Krumme AA, Schneeweiss S, Shrank WH, Brill G, Pezalla EJ, Spettell CM, Brennan TA, Matlin OS, Avorn J, Choudhry NK (2014) Patterns of initiation of oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation-quality and cost implications. Am J Med 127(1075–82):e1

Weitz JI, Semchuk W, Turpie AG, Fisher WD, Kong C, Ciaccia A, Cairns JA (2015) Trends in prescribing oral anticoagulants in Canada, 2008–2014. Clin Ther 37(2506–2514):e4

Kirley K, Qato DM, Kornfield R, Stafford RS, Alexander GC (2012) National trends in oral anticoagulant use in the United States, 2007–2011. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 5:615–621

Barnes GD, Lucas E, Alexander GC, Goldberger ZD (2015) National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med 128(1300–5):e2

Steinberg BA, Holmes DN, Piccini JP, Ansell J, Chang P, Fonarow GC, Gersh B, Mahaffey KW, Kowey PR, Ezekowitz MD, Singer DE, Thomas L, Peterson ED, Hylek EM, Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF) Investigators and Patients (2013) Early adoption of dabigatran and its dosing in US patients with atrial fibrillation: results from the outcomes registry for better informed treatment of atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2:e000535

Andrade JG, Krahn AD, Skanes AC, Purdham D, Ciaccia A, Connors S (2015) Values and preferences of physicians and patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who receive oral anticoagulation therapy for stroke prevention. Can J Cardiol 32(6):747–753

Barnes GD, Kaatz S, Winfield J, Gu X, Haymart B, Kline-Rogers E, Kozlowski J, Beasley D, Almany S, Leyden T, Froehlich JB (2014) Warfarin use in atrial fibrillation patients at low risk for stroke: analysis of the Michigan anticoagulation quality improvement initiative MAQI2. J Thromb Thrombolysis 37:171–176

Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY (2010) A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro heart survey. Chest 138:1093–1100

Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briet E (1993) A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost 69:236–239

Cockcroft DW, Gault MH (1976) Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16:31–41

Adelborg K, Grove EL, Sundboll J, Laursen M, Schmidt M (2016) Sixteen-year nationwide trends in antithrombotic drug use in Denmark and its correlation with landmark studies. Heart. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309402

Baker D, Wilsmore B, Narasimhan S (2016) Adoption of direct oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Intern Med J 46:792–797

Hanemaaijer S, Sodihardjo F, Horikx A, Wensing M, De Smet PA, Bouvy ML, Teichert M (2015) Trends in antithrombotic drug use and adherence to non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants in the Netherlands. Int J Clin Pharm 37:1128–1135

Pollack CV Jr, Reilly PA, Eikelboom J, Glund S, Verhamme P, Bernstein RA, Dubiel R, Huisman MV, Hylek EM, Kamphuisen PW, Kreuzer J, Levy JH, Sellke FW, Stangier J, Steiner T, Wang B, Kam CW, Weitz JI (2015) Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal. N Engl J Med 373:511–520

Lu G, DeGuzman FR, Hollenbach SJ, Karbarz MJ, Abe K, Lee G, Luan P, Hutchaleelaha A, Inagaki M, Conley PB, Phillips DR, Sinha U (2013) A specific antidote for reversal of anticoagulation by direct and indirect inhibitors of coagulation factor Xa. Nat Med 19:446–451

Acknowledgements

The Michigan Anticoagulation and Quality Improvement Initiative is funded by the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network, which did not contribute to data collection, interpretation, or manuscript writing. Dr. Barnes is supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (2-T32-HL007853-16).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

ZH, XK, BH, XG, JK, GK—none; EKR—consultant: Janssen, ACP, board member: AC Forum; SA—consulting fees/honoraria: Kona, Trice Orthopedics, Micardia; ownership/partnership/principal: Biostar Ventures, Ablative Solutions, research/research grants: Boston Scientific Watchman, Abbott Absorb trial; SK—consultant: BI, Janssen Dalichi Sankyo, Bristol Myer Squibb, Pfizer, speaker’s bureau: Janssen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myer Squibb, Pfizer, CSL Behring; JF—consultant Merck, Bristol Myer Squibb, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Janssen Pharmaceuticals; research grants: Fibromuscular Disease Society of America, Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan; GB—consulting for Portola and Aralez, research grants from Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan and BMS/Pfizer.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hale, Z.D., Kong, X., Haymart, B. et al. Prescribing trends of atrial fibrillation patients who switched from warfarin to a direct oral anticoagulant. J Thromb Thrombolysis 43, 283–288 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-016-1452-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-016-1452-2