Abstract

In the present study we aimed to investigate the role of social support, particularly emotional support, on work-family conflict (WFC) and employment-related guilt among employed mothers. Achieving an optimal work-family balance is difficult, especially for employed mothers with young children. Previous research has found support to be a key factor in helping to alleviate conflict. However, determining which types of support are most beneficial is an important issue to be investigated. Using path analysis, we examined the effect of three sources of social support—emotional spousal support, emotional supervisory support, and instrumental spousal support—on WFC and employment-related guilt. Voluntary domestic support, paid domestic support, and number of children were control variables. Data were collected from 201 employed Turkish mothers who have at least one child below the age of 10. Participants were between 25 and 47 years-old (M = 33.6, SD = 4.4). Spousal and supervisory emotional support were significant predictors of WFC for employed mothers. Moreover, supervisory support was a significant predictor of employment-related guilt. Implications of the results are discussed with reference to cultural context, and recommendations are provided for professionals in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Because household responsibilities are often a “second shift” for employed mothers who remain largely responsible for childcare and household chores (Bianchi et al. 2000), achieving an optimal balance between work and family can be difficult for employed mothers with young children. Work-family conflict (WFC) occurs when a person’s work-related responsibilities interfere with their family-related responsibilities, whereas family-work conflict (FWC) occurs when a person’s family-related responsibilities interfere with their work-related responsibilities (Galovan et al. 2010). Married people experience more FWC compared to single people (Herman and Gyllstrom 1977). Additionally, demanding work (Ollo-López and Goñi-Legaz 2017), having a child or a baby (Beutell and Greenhaus 1980; Greenhaus and Kopelman 1981), and living in a large family are associated with increased FWC (Cartwright 1978; Keith and Schafer 1980). Women experience more WFC and FWC compared to men (Koura et al. 2017; Van Daalen et al. 2006; Voydanoff 2004; Williams and Alliger 1994), and the experience of WFC may lead to feelings of employment-related guilt (Holcomb 1998).

Social support, both at home and in the workplace, is key in helping mothers to overcome work-family conflict. With support, employed mothers feel better able to balance work and family roles. However, not all forms of support are equal. According to Hobfoll’s (1989) conservation of resources theory, social support is beneficial only when it is relevant to situational needs. Hobfoll states that “people strive to retain, protect and build resources and that what is threatening to them is the potential or actual loss of these valued resources” (p. 516). Support comes from different sources including from family or from within the workplace, and it is important to explore the differential effects of each on WFC and FWC. Previous research has shown that various forms of social support are related to WFC, including spousal support (Adams et al. 1996; Aycan and Eskin 2005; Ely et al. 2014), family support (Blanch and Aluja 2012), paid domestic support (Spector et al. 2007), and organizational support (Alison 2009; Dutton et al. 1994; Golden-Biddle and Rao 1997). Although previous studies have highlighted the different types of support and their relationships with work family conflict, few have directly compared these types of support. Further, emotional and instrumental support have not always been distinguished in previous studies (Adams et al. 1996).

Studies show that women provide more emotional support compared to men (Reis 1998), which suggests that women married to men may receive less emotional support than other sources of support. Emotional spousal support has shown to be a predictor of well-being (Biehle and Mickelson 2012; Thoits 1995) and WFC (e.g., Michel et al. 2011). Even in countries which support the employment of women and favor gender equality, women are expected to take on more of the household and childcare duties (Hagqvist et al. 2017). Moreover, women who adopt more traditional gender roles, such as women in Turkey, are more likely to believe that home care and childcare are their own responsibilities. Thus, a lack of spousal emotional support could be a key factor leading to higher stress, perceptions of greater WFC, and negative emotions such as guilt. Additionally, when emotional support is lacking at home, we would further expect a lack of emotional supervisor support to affect employed mothers’ experiences of WFC, FWC and employment-related guilt. In the present study, we examine the effect of three types of support: emotional spousal, instrumental spousal, and emotional supervisory on WFC, FWC and employment-related guilt of employed mothers who have at least one child below the age of 10. In line with the theory of conservation of resources, we hypothesize that, for employed Turkish mothers, emotional support will be more effective in alleviating WFC compared to the other forms of support.

We also examine the influence of other types of domestic support including paid and voluntary domestic support. Results of previous research on the effects of paid and voluntary domestic support on WFC are contradictory (Luk and Shaffer 2002; Spector et al. 2004, 2007), and to the best of our knowledge the effect of different types of domestic support on feelings of employment-related guilt has not been investigated. When mothers have support at home, we would expect lower FWC. However, they may also experience higher guilt due to having to ask others (e.g., their parents) for help. In addition, the societal expectation that mothers should be with their children for a long period (Guendouzi 2006) may cause mothers who receive domestic help to feel that they are failing to meet the demands of society, leading to feelings of guilt.

The contributions of our paper to the current literature are twofold. First, we expand theoretically and empirically on our understanding of the effect of emotional support on employed mothers’ experiences of WFC and guilt. The importance of social support for dealing with WFC has been documented in multiple studies, however it is not known whether emotional support is more beneficial for employed mothers compared to instrumental support. Second, our research gives us the opportunity to compare other forms of support at home, including voluntary domestic support and paid support. In countries with more collectivist cultures, such as Turkey, mothers receive domestic support from their parents, however, the differential effects of voluntary or paid support on employment-related guilt has not been investigated.

Gender Roles in Turkey

Studies of WFC show clear cross-cultural differences based on the gender roles associated within a culture. Ollo-López and Goñi-Legaz (2017) showed that perceptions of work-family relationships vary across cultures. In Turkey, mothers have more expressive roles defined as “providing more emotional support to spouse, the children, the grandparents, keeping the family united, maintaining a pleasant environment…” (Ataca 2009, p.117) and more childcare roles compared to fathers (Ataca 2009), meaning that they have more household responsibilities. Although intrafamily relations have become more equalitarian in recent years, as exemplified by increased shared decision making, communication and/or role sharing between women and their spouses (Ataca and Sunar 1999), stereotypes relating to household responsibilities persist (Günay and Bener 2011; Imamoğlu 1991). Even when men take on more responsibility at home, woman retain their perceptions about traditional gender roles (Eken 2006). According to the study by Ollo-López and Goñi-Legaz (2017), Turkey is one of the least egalitarian countries among 16 European countries. In a highly egalitarian society women have more opportunities to enter the labor market, and the roles allocated to men and women are less distinct. However, Turkey can be characterized as a country with a more traditional gendered division of work.

Support and Work-Family Conflict

Support has been shown to be a key factor in helping individuals to deal with work-family conflict (Ferguson et al. 2012; Lapierre and Allen 2006; Michel et al. 2010; Pluut et al. 2018; Spector et al. 2007). For employed mothers, support at home includes spousal support, paid domestic support, and voluntary domestic support. Employed women with younger children will be more likely to hire professional help or to seek voluntary domestic support (e.g., from their parents). Voluntary support has previously been studied in the context of elder domestic support, defined as support from the parents of either partner (Lu et al. 2009). Previous research shows that support from other family members is related to WFC and FWC (Lu et al. 2009; Spector et al. 2004). Domestic support is more common in collectivist cultures (Spector et al. 2004) because people living in collectivist cultures are closer to their extended family members (Kagitcibasi 2005), making it easier to obtain domestic support. For example, in Turkey it is common to seek domestic help from mothers or mothers-in-law. Although research into voluntary domestic support is lacking, a few studies have shown that elder domestic help is negatively related to both types of WFC (Lu et al. 2009; Spector et al. 2004).

Another source of support which may lessen WFC is paid domestic help (Spector et al. 2004) in which women hire someone to support them at home and with childcare. In their study, Spector et al. (2004) found that although elder domestic help was negatively related to both types of WFC, paid domestic help was not related to WFC. Moreover, Luk and Shaffer (2002) showed that although paid domestic help was related to a decrease in family role demands, it was not related to FWC and WFC. Similarly, in their study Spector et al. (2007) found weak correlations between paid support and WFC. Although studies comparing voluntary support and paid support have produced conflicting results, we expected that domestic support would decrease household and childcare demands which would in turn reduce feelings of WFC and FWC. Thus we hypothesized that employed mothers who receive paid or voluntary domestic support will experience lower WFC and FWC compared to mothers with no domestic support (Hypothesis 1).

Ely et al. (2014) highlighted the importance of spousal support for women who have a career plan. Studies have shown that wives whose spouses are supportive and understanding are more motivated and confident (Lu et al. 2009). Spousal support is not only important for marital satisfaction (Acitelli and Antonucci 1994; Chong and Mickelson 2016; Husaini et al. 1982) but also for health outcomes (Kiran et al. 2003; Tanaka and Lowry 2013). More generally, support from a partner protects married people from high levels of FWC (Berkowitz and Perkins 1984; Holahan and Gilbert 1979; Rosin 1990). Support can either be instrumental or emotional (Adams et al. 1996). Whereas emotional support includes features such as showing empathy, love, thoughtfulness, understanding, and the offering of advice, instrumental support is briefly summarized as help with childcare and domestic work (Aryee et al. 1999; Burke and Greenglass 1999). Emotional support increases feelings of satisfaction both at home and at work whereas instrumental support decreases the load of family responsibilities (Parasuraman et al. 1996).

Emotional support has also been found to be an important predictor of well-being (Biehle and Mickelson 2012; Heffner et al. 2004; Thoits 1995). Although wives provide more emotional support than their husbands do (Vinokur and Vinokur-Kaplan 1990), they also receive less support than their husbands do (Allen et al. 1999; Spitze and Ward 2000; Yedirir and Hamarta 2015). Further, emotional support, compared to instrumental support, is a stronger predictor of additional variables such as marital satisfaction (Leggett et al. 2012; Yedirir and Hamarta 2015). In line with these findings, we hypothesized that both emotional spousal support and instrumental spousal support will be related to WFC and FWC. However, we expected emotional spousal support to be a stronger predictor of WFC and FWC than instrumental spousal support. Specifically, we predicted that employed mothers who report receiving more emotional and instrumental spousal support will experience lower WFC and FWC (Hypothesis 2a) and that emotional spousal support will be more important in reducing WFC and FWC compared to instrumental spousal support (Hypothesis 2b).

Finally, supervisory support is the main source of support in the workplace. Supervisors have an important role in minimizing the negative impact of work-family conflict (O'Driscoll et al. 2003), reducing stress and role conflict and enhancing family functioning (Campbell-Clark 2001). Employees perceive organizational support when their supervisors show supportive behaviors (Dutton et al. 1994; Golden-Biddle and Rao 1997). Within the workplace, emotional supervisory support refers to empathic concern for the well-being of the employee and his or her family (Adams et al. 1996; Eby et al. 2005; Frone et al. 1997). Effective supervisory support includes the fostering of an environment in which employees’ family roles are acknowledged (Adkins and Premeaux 2012).

In a study of working parents, supervision was the second most important factor related to the quality of family life after a pay increase (Galinsky and Hughes 1987). Previous research showed that support from managers reduces stress, minimizes work-family problems, and positively influences family functioning (Burke 1988; Galinsky and Stein 1990; Greenhaus et al. 1987; Merton 1957; Repetti 1987). Supervisory support increases retention of employees dealing with high WFC (Chenot et al. 2009); it is a predictor of WFC (Beutell 2010); and it also predicts marital love, depressive symptoms, conflict and role overload (Ransford et al. 2008). Previous studies showed that women provide more emotional support compared to men (Reis 1998), which would increase their need for emotional support not only at home but also in the workplace. Whereas men’s well-being is mainly related to spousal support, supervisory support for women is also important for women’s well-being (Greenberger and O’Neil 1993). Thus we expected that employed mothers who report receiving more emotional supervisory support will also experience lower WFC and FWC (Hypothesis 3).

Employment-Related Guilt

Research suggests that working mothers who experience WFC may feel guilty when they feel that this conflict violates a social standard (Holcomb 1998; Piotrkowski and Repetti 1984). Although several outcomes relating to WFC have been explored, such as burnout (Jun et al. 2017; Pu et al. 2017), job and family satisfaction, and commitment (Carlson et al. 2009), few studies have explored negative emotions resulting from WFC. It is important to examine negative emotions because they may act as a mediator between WFC and individuals’ attitudes.

Employment-related guilt is one such negative emotion rarely studied in relation to WFC (Aycan and Eskin 2005; Judge et al. 2006). Guilt is defined as an emotional state which arises from misperceptions of actions and intentions (Martínez et al. 2011). Fear of violating social norms related to gender roles can lead to feelings of guilt (Morgan and King 2012). According to traditional gender roles, women, especially mothers, are expected to be warm and nurturing (Eagly et al. 2000) and to take on more responsibility at home in order to provide a stable family environment (Gutek et al. 1981). Even when mothers seek employment to contribute to household earnings, expectations of women’s responsibilities at home are maintained (Gutek et al. 1991). To satisfy these expectations, mothers accept more responsibility for housekeeping (Major 1993) and childrearing (Bianchi et al. 2000). These expectations and the notion of being a good mother are enduring social concepts which can be difficult to overcome (McMahon 1995). Popular culture and the media portrays mothers as fundamental to the permanence of family life (Kaplan 1992), supporting the ideal of motherhood at home (Cheal 1991).

Additional questions relating to the quality of care and amount of time spent with children are debated (Guendouzi 2006). Although some studies claim that the quality of childcare is most important, there is still a stigma surrounding working mothers and the care of children (Zimmerman et al. 2001). It is not surprising then that working mothers have feelings of guilt (Guendouzi 2006; Mickelson et al. 2013). Employed mothers feel guilty when they perceive that their work life negatively impacts their family life, particularly if it negatively affects their children and if they have to leave their children with a caregiver in order to go to work.

In addition to expectations of family life, there are also expectations of work life. These expectations place a high demand on the time and energy of working mothers (Bianchi et al. 2006). In other words, the expectations placed on mothers at home and in the workplace, combined with the limited time and resources that women have to dedicate to meeting these expectations, may lead to feelings of guilt for working mothers (Bianchi et al. 2006). Along with WFC, employment-related guilt may be experienced due to nonconformity to traditional gender role expectations (Borelli et al. 2014). It was found that working mothers have high levels of work-family guilt compared to working fathers (Borelli et al. 2014).

In the present study then, we expected that mothers who experience WFC will have higher employment-related guilt. Mothers who report high WFC will struggle more with the demands of family because of the high demands at work. Receiving social support will be important. We expected that emotional support both at home and in the workplace would decrease employment-related guilt. When mothers feel that they are unable to fulfill their household duties, social support, including empathic understanding, would reduce these perceptions of failure, and thus decrease feelings of employment-related guilt. Thus we proposed three additional hypotheses: (a) that mothers who report receiving more emotional spousal support, instrumental spousal support, and emotional supervisory support will have lower employment-related guilt (Hypothesis 4), (b) that employed mothers who experience higher WFC will have higher employment-related guilt (Hypothesis 5), and (c) that employed mothers who receive paid and voluntary domestic support will experience lower employment-related guilt compared to mothers with no domestic support (Hypothesis 6).

Previous studies have also shown a positive association between the number of children an individual has and WFC (Grzywacz and Marks 2000; Lambert et al. 2006). However, Okonkwo (2014) found no significant association between the two variables, and this non-finding was explained in line with traditional gender roles in Nigeria. In a sample of American employees, Adkins and Premeaux (2012) found a positive association between number of children and WFC. Given that the role played by number of children is unclear, we controlled for it in our models.

Overall then, the combined hypotheses and the conceptual model to be tested are summarized as follows: Emotional spousal support, instrumental spousal support, and emotional supervisory support are related to work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and employment-related guilt. Furthermore, WFC is related to employment-related guilt while voluntary domestic support, paid domestic support, and number of children are controlled for in the model.

Method

Participants

Fully 201 employed mothers living in Turkey participated in our study. Participants were between 25 and 47 years-old (M = 33.6, SD = 4.4). A majority (n = 135, 67%) of the mothers had a university degree, 18% (n = 37) had a post education degree, and 14% (n = 29) had a high school degree. More than half the participants were working in private organizations (n = 123, 61%). Fully 67% (n = 135) of the participants had 1 child, 29% (n = 58) had two children, and 4% (n = 8) had three or more children. One-quarter (n = 50) of the participants had worked for more than 10 years in the same organization, 30% (n = 61) for 6–10 years and 35% (n = 70) for 1–5 years. One in five (n = 40) mothers reported receiving paid domestic support whereas 35% (n = 71) received voluntary domestic support from family members.

Procedure and Measures

Data were collected from employed mothers living in Istanbul, one of the largest industrialized cities in Turkey. Participants were employed married women who had at least one child below the age of 10 living at home. The age of a child in a family is an important determinant of feelings of WFC. Studies have shown that there is a negative relationship between the age of a child and WFC (Frone and Yardley 1996). Employees who had a child below the age of 6 reported higher WFC compared to employees with an adolescent between the ages of 13 and 18 (Bennett et al. 2017). Children who are younger than 10 require more care and guidance because they are too young to be left alone at home and are still in elementary school. Participants working in public or private companies were asked to complete a 15 min online survey. Participants were recruited through snowball sampling in which recruitment emails were sent directly to personal contacts who were then asked to forward the invitation to their network. The survey was hosted by Survey Monkey, and all data were sent to and stored on this server. Prior to data collection, approval from the Institutional Review Board at Bahcesehir University was given, and all participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Demographics

Participants were asked to indicate their age, marital status, organizational tenure, type of organization (private/ public), the number of children they have, the age of their children, and other types of support received (voluntary or paid domestic support).

Work-Family Conflict

A ten-item scale developed by Netemeyer et al. (1996), and standardized by Aycan and Eskin (2005), was used to measure work-family conflict. The scale contains five items which measure family-to-work conflict and five items which measure work-to-family conflict. Sample items include: “The amount of time my job takes up makes it difficult to fulfill family responsibilities” (WFC) and “I have to put off doing things at work because of demands on my time at home” (FWC). Responses were made using a 5-point Liker-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher summed scores indicating greater feelings of conflict. For the present sample, the internal consistency of the WFC scale was .92 and of the FWC scale was .90.

Employment-Related Guilt

Feelings of guilt due to working (and, therefore, not being able to spend as much time with family) was measured by using a scale developed by Aycan and Eskin (2005). Sample items of the scale include: “I feel guilty for going to work and leaving my children every day” and “I feel guilty for not being able to spend as much time as I wish with my children.” Responses were given using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), and they were summed so that higher scores indicate greater levels of perceived guilt. Cronbach’s alpha was .91 in our study.

Supervisor Support

Three items, developed by Campbell-Clark (2001), were used to measure employees’ perceived supervisor support in the workplace. This scale measures emotional supervisor support; the three items are: “My supervisor understands my family demands,” “My supervisor listens when I talk about my family,” and “My supervisor acknowledges that I have obligations as a family member.” Ratings were made on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and then summed so that higher scores indicate stronger supervisor support. Cronbach’s alpha was .92 in the present study.

Spousal Support

Spousal support was measured with the 44-item Family Support Inventory developed by King et al. (1995). This scale has two subscales: an Emotional Sustenance subscale consisting of 29 items and an Instrumental Assistance subscale consisting of 15 items. Emotional sustenance includes behaviors and attitudes which provide encouragement, understanding, and attention toward the spouses, and instrumental assistance includes behaviors and attitudes aimed at assisting daily family/household operations. Responses were given using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale was adapted to the Turkish language by Aycan and Eskin (2005). Sample items of the scale include: “When I succeed at work, my spouse shows that he is proud of me” and “When something at work is bothering me, my spouse shows he understands how I’m feeling.” The internal consistency of the emotional sustenance scale was .97 and of the instrumental assistance was .92 for the present sample. Items for each subscale were summed such that higher scores on each reflect greater levels of spousal support. The order of measures in the survey parallel their order of presentation here.

Results

Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations for the measured variables are shown in Table 1. WFC was negatively correlated with emotional spousal support and supervisor support as well as positively correlated with employment-related guilt. On the other hand, FWC was negatively correlated with emotional spousal support, instrumental spousal support, and supervisory support as well as positively correlated with employment-related guilt. Finally, the number of children was found to relate only to employment-related guilt (see Table 1), but this correlation was negative. In other words, mothers with more children reported lower employment-related guilt. Although a significant correlation was found between the two variables, the proportion of participants who had three children was only 4%, while 67% of the participants had one child, so the groups were unbalanced.

We examined differences between mothers who were receiving paid domestic support (n = 40), voluntary domestic support (n = 71), and no support (n = 90) in terms of their experiences of WFC, FWC, and employment-related guilt using a MANOVA. A test of the homogeneity of variances was not significant (p = .42). Results showed no significant difference in WFC (Mpaid = 14.8, SD = 4.4; Mvol = 15.5, SD = 4.9; Mnone = 14.9, SD = 4.7) and FWC (Mpaid = 11.1, SD = 3.8; Mvol = 11.4, SD = 4.1; Mnone = 12.5, SD = 4.6) across the three groups, F(2,198) = 6.44, p < .01. Therefore, Hypothesis 1, which predicted that mothers with these supports would experience lower WFC and FWC than would mothers without supports, was rejected.

In order to test our proposed model, we conducted a path analysis using AMOS 21.0. Moreover, in other multivariate procedures, hypothesis testing is more difficult compared to SEM (Byrne 2001). Thus, by using this analysis we were able to include latent variables in the model and test the impact of one variable on the others by modeling causal direction. In the model, emotional spousal support, instrumental spousal support, and emotional supervisor support were tested as predictors of WFC, FWC and employment-related guilt while two types of domestic support (voluntary domestic support and paid domestic support) and number of children were included as control variables.

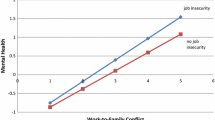

Composite scores for each variable were used in our model. Model fit was assessed using several fit indices as suggested by Bentler (1990) and Kline (1998). The goodness of fit indices suggested that the data fit the tested model well: χ2 = 4.49, χ2/df = 1.49, p = .21, GFI = .99, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .05. However, not all estimated paths were significant (see Table 2). According to the results, emotional spousal support was a significant predictor both for WFC and FWC, but instrumental spousal support was not. Therefore, Hypothesis 2a, which predicted that greater support would be related to less WFC and FWC, was supported for emotional but not for instrumental support, indicating that emotional support is more important than instrumental support in line with Hypothesis 2b. In addition, emotional supervisory support was a significant predictor of both WFC and FWC, supporting Hypothesis 3 (see Table 2).

Turning to Hypotheses 4–6, which brought in women’s reported guilt, emotional supervisory support and WFC were significant predictors of employment-related guilt, which supported Hypothesis 5 and partially supported Hypothesis 4 (see Table 2). However, both forms of spousal support were not related to women’s reported guilt, unlike the positive relationships we predicted in Hypothesis 4. In sum and in line with our expectations, emotional support from both spouse and supervisor were significant predictors of WFC and FWC for employed mothers even when controlling for voluntary and paid domestic support and number of children. Additionally, mothers who experienced supervisory support had lower employment-related guilt.

Results of an one-way MANOVA showed a significant difference in the experience of employment-related guilt across the three groups (mothers who received paid domestic support, voluntary domestic support, and no support), F(2,198) = 6.44, p = .002, ƞρ2 = .061. Contrary to our expectations post-hoc comparisons showed that (p = .001, d = .73) mothers who receive voluntary domestic support reported higher employment-related guilt (M = 28.69, SD = 8.02) compared to mothers who receive paid domestic support (M = 22.70, SD = 8.31). Additionally, mothers who receive no domestic support reported higher employment-related guilt (M = 26.82, SD = 8.84, p = .03, d = .48) compared to mothers who receive paid domestic support. In sum, women who reported having paid domestic support reported lower levels of guilt compared to women with no support and voluntary support.

Discussion

Work-family conflict is an important source of stress which is related to physical and psychological ill-health (Bacharach et al. 1991; Burke 1988; Frone et al. 1992; Livingston and Judge 2008). In recent years researchers have explored possible predictors of WFC in order to reduce experiences of conflict among employed parents, with a particular aim to protect mental health and increase positive work-related outcomes. In a study by Ollo-López and Goñi-Legaz (2017), Turkey was one of the top countries for reports of WFC among 16 European countries, and women experience higher WFC compared to men (Aycan and Eskin 2005).

Studies have revealed that social support is key in helping mothers to deal with WFC. However, sources of support vary in their effectiveness. The present study aimed to explore the effectiveness of different types of support for reducing WFC and employment-related guilt among mothers working in Turkey. Results revealed that emotional support, from both spouses and supervisors, were important for decreasing both WFC and FWC. By using Hobfoll’s (1989) conservation of resources theory, we can conclude that for mothers in Turkey emotional support is more of a need compared to instrumental support when they deal with work and family demands.

Differences between instrumental and emotional support were also shown in previous studies (Ganster et al. 1986; LaRocco et al. 1980). For example, Kaufmann and Beehr (1989) found that instrumental support and emotional support were differentially related to depression, boredom, and job satisfaction. Similarly, in a study by Yedirir and Hamarta (2015) emotional spousal support was found to be a stronger predictor of marital satisfaction in Turkish couples than instrumental support. Moreover, emotional spousal support was a stronger predictor of marital well-being and feelings of marital burnout compared to instrumental spousal support (Erickson 1993). Although instrumental support helps individuals to deal with the demands of the family role, emotional support boosts feelings of self-efficacy (Parasuraman et al. 1996). Parasuraman et al. (1996) suggested that instrumental support provides individuals with more time for their work role whereas emotional support changes one’s perceptions of the severity of WFC. It is known that women provide more emotional support (Vinokur and Vinokur-Kaplan 1990) but receive less (Yedirir and Hamarta 2015). Thus, emotional support can be perceived as a loss which would be threatening for women from the perspective of Hobfoll (1989). Thus, our results support findings from previous research showing that when employed mothers receive emotional support, they perceive lower levels of WFC and FWC and feel more able to deal with the demands of work and home (Parasuraman et al. 1996).

Emotional supervisory support was also tested in our model as a predictor of WFC, FWC, and employment-related guilt. Although some studies suggested supervisory support was only related to WFC (Aycan and Eskin 2005; Griggs et al. 2013), recent research suggests that support in one domain can alleviate conflict in other domains (Ferguson et al. 2012; Ollo-López and Goñi-Legaz 2017; Pluut et al. 2018). Supervisors have an influence on role conflict and they can enhance family functioning (Campbell-Clark 2001). In the present study, supervisory support was measured from the perspective of emotional support. When employed mothers feel that their supervisors are supportive of their family roles, they may feel more able to balance their roles. Thus, mothers who reported higher supervisory support, reported not only lower WFC but also lower FWC. Our results are also in agreement with those from Greenberger and O’Neil (1993) who found that, unlike for men, both spousal and supervisor support are important for women. Thus, one of the key contributions of our study is in increasing our understanding of the possible differences between emotional and instrumental support as predictors of WFC and FWC.

Our finding that WFC predicts employment-related guilt among mothers is in keeping with previous research (Aycan and Eskin 2005; Martínez et al. 2011). In one study, Livingston and Judge (2008) found that traditional people (i.e., individuals who embrace more traditional gender roles) reported higher guilt related to work and family conflict compared to egalitarian people. Traditional women identify with home (Hochschild 1989) therefore working traditional women are more likely to experience employment-related guilt, which is what would be expected in Turkey. Borelli et al. (2017) also found that mothers had higher work-family guilt compared to fathers. In other words, the finding that employed mothers who experience more severe WFC report stronger feelings of guilt was in line with our expectations.

However, an interesting finding in the present study relates to emotional supervisory support and its influence on guilt. To our knowledge, the role of support on feelings of guilt has not previously been studied. According to our results, when mothers perceive higher emotional supervisory support, they also reported lower levels of employment-related guilt. Presumably when women receive supervisory support (which includes care, empathy, and concern for family responsibilities), their perceptions of working life may be more positive, which in turn may reduce stress and feelings of conflict. Thus, supervisory support may help to facilitate the adjustment of employees to the demands of the workplace (Adkins and Premeaux 2012). In other words, by offering support, supervisors may promote positive attitudes toward employment, leading to positive emotions. Supportive supervisors may offer other benefits, such as giving employees more flexibility. This would allow mothers more time to dedicate to childcare and family demands and thus reduce feelings of guilt. In future studies it would be interesting to examine the influence of other factors relating to supervisor support such as flexibility or workload.

We also asked mothers about other types of domestic support they receive. Previous research suggests that voluntary and paid domestic support are related to severity of WFC (Griggs et al. 2013; Spector et al. 2004, 2007), but differences between types of support has not been fully examined. When comparing types of domestic support (voluntary support, paid support, and no support), we found no significant difference between the groups in terms of the perceived severity of WFC and FWC. This non-finding is in line with previous findings (Luk and Shaffer 2002). However, there was a significant difference in employment-related guilt. According to our results, mothers who receive voluntary support report the most guilt, followed by the no support group and the paid support group. Some previous studies have concluded that support alone is not enough to decrease WFC and to increase well-being. Mothers who experience good caregiving interactions perceive social support as positive, which is associated with well-being (see in Kossek et al. 2008). Higher quality of childcare is also related to perceptions of positive social support (Kossek et al. 2008). Thus, the childcare provider is an important consideration: childcare training and education are two predictors of perceived childcare quality. Perhaps the mothers in the present study who were paying for support perceive that support to be of higher quality than the mothers who were receiving voluntary support from their parents, especially if the former are receiving support from people with relevant childcare training. At this point it is not possible to ascertain whether significant differences are best accounted for by types of support because the three groups were not balanced and cannot be randomly assigned. Future research may benefit from the inclusion of more balanced groups of mothers receiving different types of domestic support as well as look for other factors that differentiate these groups and which may be related to their differences in reported levels of guilt.

WFC is not only related to personal and family characteristics but also to cultural factors (Crompton and Lyonette 2006; Ollo-López and Goñi-Legaz 2017). Hence it is helpful to consider the present findings from a cultural perspective. According to gender role theory (Pleck 1977), family care and household duties are the responsibility of women (Fletcher and Bailyn 2005). Although in recent years men have increasingly taken on more household and childcare responsibilities, this may not be the case for more traditional men and women. In other words, although women’s participation in the workplace has increased, their household duties may not have decreased (Álvarez and Miles 2006) especially in a traditional culture. Turkey as a country has both eastern and western features and is in a transition period in terms of gender roles (Aycan and Eskin 2005). Although involvement in the workplace is increasing for women, Turkish urban middle-class families still maintain traditional family values (Aycan and Eskin 2005). Indeed, Turkey is one of the least egalitarian countries among 16 European countries (Ollo-López and Goñi-Legaz 2017) so traditional gender roles persist.

Moreover, unlike individualist cultures, in collectivist cultures like Turkey, work and family domains are generally viewed as integrated (Yang 2005) which is important for understanding the concept of WFC (Aycan 2008). From this cultural perspective, the significant effect of emotional spousal support but not instrumental spousal support on WFC and FWC might reflect the strong ties women in eastern cultures such as Turkey have to their traditional roles of being a mother and homemaker (Pedersen et al. 2009). Emotional spousal support predicts marital satisfaction of traditional women better than it does for egalitarian women for whom marital satisfaction and conflict are predicted by both instrumental and emotional support (Mickelson et al. 2006). Our results are in line with this finding.

Effects of supervisory support on employment-related variables may also be related to cultural differences. Turkey scores highly on Hofstede’s (2001) power distance dimension, which tells us that Turkish employees feel comfortable with hierarchy and that the ideal boss is a father figure. Thus, for people in eastern cultures, a supervisor has a more paternalistic role (Abdullah 1996) whereas in western cultures the relationship between employees and employers resembles a cost-benefit relationship (Restubog and Bordia 2007). In collectivist cultures, a superior is also thought of as a father or a mother figure. In other words, superiors take care of employees’ personal issues as well as their professional issues (Abdullah 1996) which may explain our findings showing the effects of supervisory support on WFC, FWC, and employment-related guilt. At this point it is not possible to ascertain whether the findings are related to cultural values or gender differences. It would be interesting for future studies to examine this issue further.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

There are limitations to the present study. First and foremost, our data were self-report and cross-sectional in nature, limiting the inference of causal associations among the study variables. Nevertheless, our research provides a useful framework and a model for future longitudinal research, particularly focusing on the role of emotional support on WFC. Because it is not easy to collect data from employed mothers, we had a limited number of participants. Therefore, our results require replication in a larger sample. In addition, future studies could examine these issues using participants from different cultures, and the quality of support received could be included as another variable. Ratings of conflict and guilt may also be affected by mood. Therefore, future studies should include a mood scale to control for this possible effect. Finally, employed fathers might be included in future studies in order to compare the effects of different types of spousal support on WFC among mothers and fathers.

Practice Implications

Our findings have implications for counselors, managers, and policymakers. From a practical perspective, our study highlights the importance of emotional support for helping employed mothers to deal with WFC and employment-related guilt. Supervisors who show empathy and concern for the well-being of the employee and her family, as well as spouses who show empathy and love and who offer advice when it is needed, will play vital roles in helping employed women deal with conflict between work and family. Training intervention programs can be developed to increase awareness of these issues. Emotion-based interaction training to promote communication between spouses and coworkers would be particularly beneficial.

Conclusion

Sometimes a solution for a difficult problem is less complex than we might imagine. Work-family conflict is a core problem both for men and women, as well as for management and policymakers. Yet the debate about the disadvantages of working mothers continues in some countries. Our research with employed Turkish mothers shows that certain types of support can help to reduce WFC. In particular, a spouse who shows empathy and love, who is thoughtful and understanding and who offers advice when needed, provides an important source of social support for working mothers. Additionally, a supervisor with empathic understanding for the well-being of women and their families can help to create more favorable working and home environments for working mothers of dependent children.

References

Abdullah, A. (1996). Going global: Cultural dimensions in Malaysian management. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Institute of Management.

Acitelli, L. K., & Antonucci, T. C. (1994). Gender differences in the link between marital support and satisfaction in older couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 688–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.688.

Adams, G. A., King, L. A., & King, D. W. (1996). Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work–family conflict with job and life satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.411.

Adkins, C. L., & Premeaux, S. F. (2012). Spending time: The impact of hours worked on work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.09.003.

Alison, C. (2009). Connecting work-family policies to supportive work environments. Group and Organization Management, 34(2), 206–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601108330091.

Allen, S. M., Goldscheider, F., & Ciambrone, D. A. (1999). Gender roles, marital intimacy, and nomination of spouse as primary caregiver. The Gerontologist, 39(2), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/39.2.150.

Álvarez, B., & Miles, D. (2006). Husbands' housework time: Does wives' paid employment make a difference? Investigaciones Economicas, 30(1), 5–31.

Aryee, S., Luk, V., Leung, A., & Lo, S. (1999). Role stressors, interrole conflict, and well-being: The moderating influence of spousal support and coping behaviors among employed parents in Hong Kong. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(2), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1667.

Ataca, B. (2009). Turkish family structure and functioning. In S. Bekman & A. Aksu-Koc (Eds.), Perspectives on human development, family, and culture (pp. 108–125). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ataca, B., & Sunar, D. (1999). Continuity and change in Turkish urban family life. Psychology and Developing Societies, 11(1), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/097133369901100104.

Aycan, Z. (2008). Cross-cultural approaches to work-family conflict. In K. Korabik, D. S. Lero, & D. L. Whitehead (Eds.), Handbook of work-family integration: Research, theory and best practices (pp. 353–370). Boston: Academic Press.

Aycan, Z., & Eskin, M. (2005). Relative contributions of childcare, spousal support, and organizational support in reducing work–family conflict for men and women: The case of Turkey. Sex Roles, 53(7–8), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-7134-8.

Bacharach, S. B., Bamberger, P., & Conley, S. (1991). Work-home conflict among nurses and engineers: Mediating the impact of role stress on burnout and satisfaction at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030120104.

Bennett, M. M., Beehr, T. A., & Ivanitskaya, L. V. (2017). Work-family conflict: Differences across generations and life cycles. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 32(4), 314–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-06-2016-0192.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238.

Berkowitz, A. D., & Perkins, H. W. (1984). Stress among farm women: Work and family as interacting systems. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 46, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.2307/351874.

Beutell, N. J. (2010). Work schedule, work schedule control and satisfaction in relation to work-family conflict, work-family synergy, and domain satisfaction. Career Development International, 15(5), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431011075358.

Beutell, N. J., & Greenhaus, J. H. (1980). Some sources and consequences of interrole conflict among married women. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Eastern Academy of Management, 17, 2–6.

Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces, 79(1), 191–228. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/79.1.191.

Bianchi, S. M., Robinson, J. P., & Milkie, M. A. (2006). Changing rhythms of American family life. New York: Russell Sage.

Biehle, S. N., & Mickelson, K. D. (2012). Provision and receipt of emotional spousal support: The impact of visibility on well-being. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 1(3), 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028480.

Blanch, A., & Aluja, A. (2012). Social support (family and supervisor), work–family conflict, and burnout: Sex differences. Human Relations, 65(7), 811–833. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712440471.

Borelli, J. L., Nelson, S. K., & River, L. R. (2014). Pomona work and family assessment (Unpublished document). Pomona College, Claremont, CA.

Borelli, J. L., Nelson, S. K., River, L. M., Birken, S. A., & Moss-Racusin, C. (2017). Gender differences in work-family guilt in parents of young children. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 76(5–6), 356–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0579-0.

Burke, R. J. (1988). Some antecedents of work-family conflict. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 3(4), 287–302.

Burke, R. J., & Greenglass, E. R. (1999). Work–family conflict, spouse support, and nursing staff well-being during organizational restructuring. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4(4), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.4.4.327.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Campbell-Clark, S. (2001). Work cultures and work/family balance. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 58, 348–365. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1759.

Carlson, D. S., Grzywacz, J. G., & Zivnuska, S. (2009). Is work—family balance more than conflict and enrichment? Human Relations, 62(10), 1459–1486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709336500.

Cartwright, L. K. (1978). Career satisfaction and role harmony in a sample of young women physicians. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 12(2), 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(78)90033-7.

Cheal, D. J. (1991). Family and the state of theory. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Chenot, D., Benton, A. D., & Kim, H. (2009). The influence of supervisor support, peer support, and organizational culture among early career social workers in child welfare services. Child Welfare, 88(5), 129–147.

Chong, A., & Mickelson, K. D. (2016). Perceived fairness and relationship satisfaction during the transition to parenthood: The mediating role of spousal support. Journal of Family Issues, 37(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13516764.

Crompton, R., & Lyonette, C. (2006). Work-life “balance” in Europe. Acta Sociologica, 49(4), 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699306071680.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 39–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393235.

Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., & Diekman, A. B. (2000). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. In T. Eckes & H. M. Trautner (Eds.), The developmental social psychology of gender (pp. 123–174). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Eby, L. T., Casper, W. J., Lockwood, A., Bordeaux, C., & Brinley, A. (2005). A retrospective on work and family research in IO/OB: A content analysis and review of the literature (1980–2002). Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(1), 124–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.11.003.

Eken, H. (2006). Toplumsal cinsiyet olgusu tcmelinde mesle|e ilicldn rol ile aile ici rol etkileçimi: Turk Silahli Kuwetlerindeki kadm subaylar. [Occupational and domestic role interaction among female officers in Turkish Armed Forces on the basis of gender]. Selçuk University, Journal of Social Sciences, 15, 247–278.

Ely, R. J., Stone, P., & Ammerman, C. (2014). Rethink what you “know” about high-achieving women. Harvard Business Review, 92(12), 100–109.

Erickson, R. J. (1993). Reconceptualizing family work: The effect of emotion work on perceptions of marital quality. Journal of Marriage and Family, 55(4), 888–900. https://doi.org/10.2307/352770.

Ferguson, M., Carlson, D., Zivnuska, S., & Whitten, D. (2012). Support at work and home: The path to satisfaction through balance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.001.

Fletcher, J. K., & Bailyn, L. (2005). The equity imperative: Redesigning work for work-family integration. In E. E. Kossek & S. J. Lambert (Eds.), LEA's organization and management series. Work and life integration: Organizational, cultural, and individual perspectives (pp. 171–189). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Frone, M. R., & Yardley, J. K. (1996). Workplace family-supportive programmes: Predictors of employed parents' importance ratings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 69(4), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1996.tb00621.x.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1997). Relation of work–family conflict to health outcomes: A four year longitudinal study of employed parents. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(4), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00652.x.

Galinsky, E., & Hughes, D. (1987). The Fortune magazine child care study. Paper presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, New York, NY.

Galinsky, E., & Stein, P. J. (1990). The impact of human resource policies on employees: Balancing work/family life. Journal of Family Issues, 11(4), 368–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251390011004002.

Galovan, A. M., Fackrell, T., Buswell, L., Jones, B. L., Hill, E. J., & Carroll, S. J. (2010). The work–family interface in the United States and Singapore: Conflict across cultures. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 646–656. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020832.

Ganster, D. C., Fusilier, M., & Mayes, B. (1986). The role of social support in the experience of stress at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.1.102.

Golden-Biddle, K., & Rao, H. (1997). Breaches in the boardroom: Organizational identity and conflicts of commitment in a nonprofit organization. Organization Science, 8(6), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.8.6.593.

Greenberger, E., & O’Neil, R. (1993). Spouse, parent, worker: Role commitments and role-related experiences in the construction of adults’ well-being. Developmental Psychology, 29(2), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.29.2.181.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Kopelman, R. E. (1981). Conflict between work and nonwork roles: Implications for the career planning process. Human Resource Planning, 4(1), 1–10.

Greenhaus, J. H., Bedeian, A. G., & Mossholder, K. W. (1987). Work experiences, job performance, and feelings of personal and family well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31(2), 200–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(87)90057-1.

Griggs, T. L., Casper, W. J., & Eby, L. T. (2013). Work, family and community support as predictors of work–family conflict: A study of low-income workers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 82(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.11.006.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work–family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.111.

Guendouzi, J. (2006). “The guilt thing”: Balancing domestic and professional roles. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(4), 901–909. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00303.x.

Günay, G., & Bener, Ö. (2011). Perception of family life in frame of gender roles of women. TSA, 15(3), 157–171.

Gutek, B. A., Nakamura, C. Y., & Nieva, V. F. (1981). The interdependence of work and family roles. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020102.

Gutek, B. A., Searle, S., & Klepa, L. (1991). Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(4), 560–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.4.560.

Hagqvist, E., Gådin, K. G., & Nordenmark, M. (2017). Work–family conflict and well-being across Europe: The role of gender context. Social Indicators Research, 132(2), 785–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1301-x.

Heffner, K. L., Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Loving, T. J., Glaser, R., & Malarkey, W. B. (2004). Spousal support satisfaction as a modifier of physiological responses to marital conflict in younger and older couples. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 27(3), 233–254. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBM.0000028497.79129.ad.

Herman, J. B., & Gyllstrom, K. K. (1977). Working men and women: Inter-and intra-role conflict. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 1(4), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1977.tb00558.x.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513.

Hochschild, A. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York: Viking.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Holahan, C. K., & Gilbert, L. A. (1979). Conflict between major life roles: Women and men in dual career couples. Human Relations, 32(6), 451–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872677903200602.

Holcomb, B. (1998). Not guilty: The good news about working mothers. New York: Scribner.

Husaini, B. A., Neff, J. A., Newbrough, J. R., & Moore, M. C. (1982). The stress-buffering role of social support and personal competence among the rural married. Journal of Community Psychology, 10(4), 409–426. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(198210)10:4<409::AID-JCOP2290100410>3.0.CO;2-D.

İmamoğlu, O. (1991). Changing intra-family roles in a changing world. Paper presented at the Seminar on the Individual, the Family and the Society in a Changing World, Istanbul, Turkey

Judge, T. A., Ilies, R., & Scott, B. A. (2006). Work–family conflict and emotions: Effects at work and at home. Personnel Psychology, 59(4), 779–814. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00054.x.

Jun, P., Hanpo, H., Ruiyang, M., & Jinyan, S. (2017). The effect of psychological capital between work-family conflict and job burnout in Chinese university teachers: Testing for mediation and moderation. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(14), 1799–1807. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316636950.

Kagitcibasi, C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(4), 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022105275959.

Kaplan, M. M. (1992). Mothers' images of motherhood: Case studies of twelve mothers. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Kaufmann, G. M., & Beehr, T. A. (1989). Occupational stressors, individual strains, and social supports among police officers. Human Relations, 42(2), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678904200205.

Keith, P. M., & Schafer, R. B. (1980). Role strain and depression in two-job families. Family Relations, 29, 83–488. https://doi.org/10.2307/584462.

King, L. A., Mattimore, L. K., King, D. W., & Adams, G. A. (1995). Family support inventory for workers: A new measure of perceived social support from family members. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16, 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160306.

Kiran, R., Mridula, A., & Subbakrishna, D. K. (2003). Coping and subjective well-being in women with multiple roles. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 49(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640030493003.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Kossek, E. E., Pichler, S. M., Meece, D., & Barratt, M. E. (2008). Family, friend, and neighbour child care providers and maternal wellbeing in low income systems: An ecological social perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 81(3), 369–391. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X324387.

Koura, U., Sekine, M., Yamada, M., & Tatsuse, T. (2017). Work, family, and personal characteristics explain occupational and gender differences in work-family conflict among Japanese civil servants. Public Health, 153, 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.08.010.

Lambert, C. H., Kass, S. J., Piotrowski, C., & Vodanovich, S. J. (2006). Impact factors on work-family balance: Initial support for border theory. Organization Development Journal, 24(3), 64–75.

Lapierre, L. M., & Allen, T. D. (2006). Work-supportive family, family-supportive supervision, use of organizational benefits, and problem-focused coping: Implications for work-family conflict and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.2.169.

LaRocco, J. M., House, J. S., & French Jr., J. R. (1980). Social support, occupational stress, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 202–218. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136616.

Leggett, D. G., Roberts-Pittman, B., Byczek, S., & Morse, D. T. (2012). Cooperation, conflict, and marital satisfaction: Bridging theory, research, and practice. Journal of Individual Psychology, 68(2), 182–199.

Livingston, B. A., & Judge, T. A. (2008). Emotional responses to work-family conflict: An examination of gender role orientation among working men and women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.207.

Lu, J.-F., Siu, O.-L., Spector, P. E., & Shi, K. (2009). Antecedents and outcomes of a fourfold taxonomy of work-family balance in Chinese employed parents. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(2), 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014115.

Luk, D. M., & Shaffer, M. A. (2002). Work and family domain stressors, structure and support: Direct and indirect influences on work-family conflict. Hong Kong: Business Research Centre, School of Business, Hong Kong Baptist University.

Major, B. (1993). Gender, entitlement, and the distribution of family labor. Journal of Social Issues, 49(3), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb01173.x.

Martínez, P., Carrasco, M. J., Aza, G., Blanco, A., & Espinar, I. (2011). Family gender role and guilt in Spanish dual-earner families. Sex Roles, 65(11–12), 813–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0031-4.

McMahon, M. (1995). Engendering motherhood: Identity and self-transformation in women's lives. New York: Guilford Press.

Merton, R. K. (1957). The role-set: Problems in sociological theory. The British Journal of Sociology, 8(2), 106–120. https://doi.org/10.2307/587363.

Michel, J. S., Mitchelson, J. K., Pichler, S., & Cullen, K. L. (2010). Clarifying relationships among work and family social support, stressors, and work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(1), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.05.007.

Michel, J. S., Kotrba, L. M., Mitchelson, J. K., Clark, M. A., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). Antecedents of work–family conflict: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(5), 689–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.695.

Mickelson, K. D., Claffey, S. T., & Williams, S. L. (2006). The moderating role of gender and gender role attitudes on the link between spousal support and marital quality. Sex Roles, 55(1–2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9061-8.

Mickelson, K. D., Chong, A., & Don, B. P. (2013). "To thine own self be true": Impact of gender role and attitude mismatch on new mothers' mental health. In J. Marich (Ed.), The psychology of women: Diverse perspectives from the modern world (pp. 1–16). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc..

Morgan, W. B., & King, E. B. (2012). The association between work-family guilt and pro- and anti-social work behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 68(4), 684–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2012.01771.x.

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 400–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400.

O'Driscoll, M. P., Poelmans, S., Spector, P. E., Kalliath, T., Allen, T. D., Cooper, C. L., … Sanchez, J. I. (2003). Family-responsive interventions, perceived organizational and supervisor support, work-family conflict, and psychological strain. International Journal of Stress Management, 10(4), 326–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.10.4.326

Okonkwo, E. (2014). Female nurses experiencing family strain interference with work: Spousal support and number of children impacts. Gender and Behaviour, 12(1), 6182–6188.

Ollo-López, A., & Goñi-Legaz, S. (2017). Differences in work–family conflict: Which individual and national factors explain them? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(3), 499–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1118141.

Parasuraman, S., Purohit, Y. S., Godshalk, V. M., & Beutell, N. J. (1996). Work and family variables, entrepreneurial career success, and psychological well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 48(3), 275–300. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1996.0025.

Pedersen, D. E., Minnotte, K. L., Kiger, G., & Mannon, S. E. (2009). Workplace policy and environment, family role quality, and positive familytowork spillover. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 30, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-008-9140-9.

Piotrkowski, C. S., & Repetti, R. L. (1984). Dual-earner families. Marriage & Family Review, 7(3–4), 99–124.

Pleck, J. H. (1977). The work-family role system. Social Problems, 24(4), 417–427. https://doi.org/10.2307/800135.

Pluut, H., Ilies, R., Curşeu, P. L., & Liu, Y. (2018). Social support at work and at home: Dual-buffering effects in the work-family conflict process. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 146, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.02.001.

Pu, J., Hou, H., Ma, R., & Sang, J. (2017). The effect of psychological capital between work– Family conflict and job burnout in Chinese university teachers: Testing for mediation and moderation. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(14), 1799–1807. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316636950.

Ransford, C. R., Crouter, A. C., & McHale, S. M. (2008). Implications of work pressure and supervisor support for fathers’, mothers’ and adolescents’ relationships and well-being in dual-earner families. Community, Work & Family, 11(1), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800701785312.

Reis, H. T. (1998). The interpersonal context of emotions: Gender differences in intimacy and related behaviors. In D. Canary & K. Dindia (Eds.), Sex differences/similarities in communication (pp. 203–231). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Repetti, R. L. (1987). Individual and common components of the social environment at work and psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(4), 710–720 http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.710.

Restubog, S. L. D., & Bordia, P. (2007). One big happy family: Understanding the role of workplace familism in the psychological contract dynamics. In A. I. Glendon, B. M. Thompson, & B. Myors (Eds.), Advances in organisational psychology (pp. 371–387). Bowen Hills: Australian Academic Press.

Rosin, H. M. (1990). The effects of dual career participation on men: Some determinants of variation in career and personal satisfaction. Human Relations, 43, 169–182 http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/001872679004300205.

Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Poelmans, S., Allen, T. D., O'Driscoll, Michael., Sanchez, J. I., ... Lu, L. (2004). A cross-national comparative study of work-family stressors, working hours, and well-being: China and Latin America versus the Anglo world. Personnel Psychology, 57(1), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.tb02486.x

Spector, P. E., Allen, T. D., Poelmans, S. A., Lapierre, L. M., Cooper, C. L., Michael, O. D., ... Brough, P. (2007). Cross-national differences in relationships of work demands, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions with work–family conflict. Personnel Psychology, 60(4), 805–835. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00092.x

Spitze, G., & Ward, R. (2000). Gender, marriage, and expectations for personal care. Research on Aging, 22(5), 451–469 http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/0164027500225001.

Tanaka, K., & Lowry, D. (2013). Mental well-being of mothers with preschool children in Japan: The importance of spousal involvement in childrearing. Journal of Family Studies, 19(2), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2599981.

Thoits, P. A. (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 53–79 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2626957.

Van Daalen, G., Willemsen, T. M., & Sanders, K. (2006). Reducing work–family conflict through different sources of social support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(3), 462–476 http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.07.005.

Vinokur, A. D., & Vinokur-Kaplan, D. (1990). "In sickness and in health": Patterns of social support and undermining in older married couples. Journal of Aging and Health, 2(2), 215–241 http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/089826439000200205.

Voydanoff, P. (2004). The effects of work demands and resources on work-to-family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(2), 398–412 https://www.jstor.org/stable/3599845.

Williams, K. J., & Alliger, G. M. (1994). Role stressors, mood spillover, and perceptions of work-family conflict in employed parents. Academy of Management Journal, 37(4), 837–868. https://doi.org/10.2307/256602.

Yang, N. (2005). Individualism-collectivism and work-family interfaces: A Sino-U.S. comparison. In S. A. Y. Poelmans (Ed.), Work and family: An international research perspective (pp. 287–318). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Yedirir, S., & Hamarta, E. (2015). Emotional expression and spousal support as predictors of marital satisfaction: The case of Turkey. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 15(6), 1549–1558. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2015.6.2822.

Zimmerman, T. S., Bowling, S. W., & McBride, R. M. (2001). Strategies for guilt among working mothers. The Colorado Early Childhood Journal, 3(1), 32–36.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and the two reviewers for their valueable comments on the previous version of the manuscript. They also thank Katie Peterson for her professional assistance with proofreading.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors confirmed that there are no conflicts of interest. No external funding was used to support this project. Prior to data collection, approval from the Institutional Review Board at Bahcesehir University was taken. All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study. Participation was unpaid and voluntary bases.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Uysal Irak, D., Kalkışım, K. & Yıldırım, M. Emotional Support Makes the Difference: Work-Family Conflict and Employment Related Guilt Among Employed Mothers. Sex Roles 82, 53–65 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01035-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01035-x