Abstract

Researchers who examine the relation of gender role attitudes to division of household labor and marital quality often overlook its relation to emotional spousal support. Moreover, research on gender and marriage often ignores how gender role attitudes may explain the link between spousal support and marital quality. Secondary data analyses on a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults examined the interaction of gender and gender role attitudes on spousal support and marital quality. Emotional spousal support predicted better marital satisfaction and less conflict for traditional women and egalitarian men, whereas both instrumental and emotional spousal support predicted better marital satisfaction for egalitarian women and traditional men. These results suggest that within, as well as between, gender differences are important for understanding the contribution of spousal support to perceived marital quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Moderating Role of Gender and Gender Role Attitudes on the Link Between Spousal Support and Well-Being

Statistics have consistently shown that married, working women often work a daily “second shift” of childcare and household chores (e.g., Bianchi, Milkie, Sayer, & Robinson, 2000; Hochschild & Machung, 1989; Pleck, 1985; Ross, 1987). Researchers have also found that women receive less emotional support from their husbands than men do from their wives (Solomon & Rothblum, 1986; Vinokur & Vinokur-Kaplan, 1990). Thus, it is not surprising that marriage appears to be less beneficial for women than for men. Specifically, married women report poorer mental and physical health (Gove, 1973) and less marital satisfaction than married men do (Noor, 1997; Voydanoff & Donnelly, 1999). Rather than marriage per se, marital quality appears to be more important for women’s well-being (Williams, 1988). Husaini, Neff, Newbrough, and Moore (1982) found that the one situation in which marriage is beneficial for women is when the husband is rated as highly supportive. But what is considered supportive? Do men and women consider the same behaviors by a spouse to be reflective of support? For that matter, do all women (or all men) consider the same spousal behaviors to be supportive?

One limitation of prior research on support in marital relationships is that researchers have tended to examine differences between gender, rather than differences within gender. By collapsing across all women or all men (i.e., “gender-as-personality-variable-perspective,” Ashmore, 1990, p. 509) important in-group differences are lost. The focus remains on the sex difference approach as opposed to the gender perspective where the emphasis lies more on the “interactional context of gender”—i.e., “gender constructs emerge from and are enacted in the interactions of daily life” (Thompson, 1993, p.558). This perspective is especially important when considering the marital relationship as one’s ideas of gender can be shaped and reshaped in the daily interactions between husbands and wives.

One important question that has not been examined systematically is whether gender role attitudes play a part in the link between spousal support and marital quality. The type of spousal support that is most beneficial to marital quality may vary depending on both an individual’s gender and his/her gender role attitudes. For instance, women with traditional gender role attitudes consider housework to be the woman’s responsibility. As such, instrumental support (defined in this paper as help with household tasks) from a husband is less often expected, and, therefore, should be less important than emotional spousal support for these wives’ perceived marital quality. By contrast, women with egalitarian gender role attitudes consider housework a shared domain. As such, instrumental support from a husband is greatly expected, and, therefore, it may be as important as emotional spousal support for these wives’ perceived marital quality. For men, on the other hand, the opposite pattern may be found; traditional men expect more instrumental spousal support from their wives than egalitarian men do. The goal of the present study was to examine whether gender role attitudes influence the relation between spousal support and marital quality (i.e., marital satisfaction and marital conflict) differentially for men and women.

Gender Role Attitudes and Division of Household Labor

The women’s movement and increased numbers of dual-career couples have led to shifts in gender role attitudes—in other words, what a husband and wife expect from themselves and each other in their marital relationship roles (Helmreich, Spence, & Gibson, 1982). Traditional notions that a wife is expected to remain at home and take care of the house, children, and family, while the husband is expected to be the breadwinner and “head of the household,” have begun to decrease and more egalitarian notions (men and women are equal in all domains) have increased among both men and women (Botkin, Weeks, & Morris, 2000). Even though Botkin et al. (2000) found significant shifts toward egalitarianism from 1961 to 1972, these attitude shifts plateaued from 1972 to 1996. Moreover, women tend to be more egalitarian in their gender role attitudes than men (e.g., Fan & Marini, 2000; King & King, 1985; Larsen & Long, 1988).

Not only have gender role attitudes changed, but, concurrently, division of household labor has also shifted. Research on division of household labor suggests that men and women are demonstrating more egalitarian behaviors than in the past (e.g., Davis & Greenstein, 2004). Since the 1960s, women have cut the time they spend on housework by nearly one-half, whereas men have nearly doubled their time (although today women are still responsible for the majority of the housework, e.g., Bartley, Blanton, & Gilliard, 2005; Bianchi et al., 2000; Coltrane, 2000). This move toward equality in household division of labor is consistent with the shift toward egalitarian attitudes.

Although the above research suggests that marital behaviors today are more egalitarian, egalitarian wives are not satisfied. In fact, Amato and Booth (1995) found that as women’s attitudes became more egalitarian, their perceived marital quality declined. In contrast, as men’s attitudes became more egalitarian, their perceived marital quality increased. So, why are egalitarian women less happy in their marriages? One explanation may stem from the finding that an ideology of marital equality does not necessarily translate into an outcome of marital equality (Blaisure & Allen, 1995). Along these lines, Hackel and Ruble (1992) found that violated support expectations (particularly division of childcare and household labor) were related to less marital satisfaction. Additionally, egalitarian women with an unequal division of household labor experience more discontent than traditional women do with an unequal division of labor (Buunk, Kluwer, Schuurman, & Siero, 2000). Voydanoff and Donnelly (1999) also found that for mothers who hold an egalitarian gender ideology, perceived unfairness of household chores to self exacerbates the relationship between hours in household chores and psychological distress. Consequently, the links between egalitarian gender attitudes, spousal support, and marital quality may be partially explained by unmet expectations regarding division of household labor.

Spousal Support and Well-Being

Does this idea extend to emotional support from a spouse? Most studies on gender role attitudes tend to focus solely on the influence of division of household labor (i.e., instrumental spousal support) on marital quality. Yet, research on social support and marriage has repeatedly found that emotional support from a spouse is a significant predictor of both greater marital satisfaction (e.g., Acitelli & Antonucci, 1994) and less marital conflict (e.g., McGonagle, Kessler, & Schilling, 1992; Schuster, Kessler, & Aseltine, 1990)—and more so for women than for men. Emotional support is thought to be more important for women’s well-being, in general, because of women’s emphasis on intimacy in relationships. Within the context of marriage, the expectation for intimacy and caring may make emotional support salient in a wife’s evaluation of marital quality (see Acitelli, 1996, for a review). On the other hand, married men’s well-being within marriage may be strongly connected to both instrumental spousal support (because of their socialized expectations for marriage and marital roles; Thompson, 1993) and emotional spousal support (because the wife is often the sole confidant for married men; Belle, 1987).

However, most researchers have examined only one domain of spousal support and its relation to marital quality. In one of the few exceptions, Erickson (1993) examined the relation of both emotional and instrumental spousal support to marital quality (but for women only). She found that, regardless of whether they were employed or not, emotional support from the spouse was a stronger predictor of marital well-being than instrumental spousal support (e.g., housework or childcare). We have located only one published study that assessed whether type of spousal support is differentially related to well-being for both married men and women. Vanfossen (1981) examined husbands, employed wives, and non-employed wives to determine if emotional support (i.e., affirmation and intimacy) and inequity (i.e., “spouse is demanding, and unwilling to reciprocate equally in the give-and-take of marriage,” p. 134) are similarly related to depression for all three groups. She found that affirmation and intimacy were important predictors of depression for both husbands and non-employed wives. For employed wives, affirmation and inequity were the most important predictors of depression. There are no published studies, to date, on the function of gender role attitudes in the link between spousal support and marital quality for men and women. In fact, a wife’s employment status is often used as a surrogate for gender role attitudes. Yet, given the economics of modern society, it is likely that couples with more traditional attitudes may include a wife who works outside the home purely for financial reasons. In other words, gender role attitudes cannot simply be assumed from a wife’s employment status.

The Present Study

In the present study, we sought to examine systematically, in a nationally representative sample, whether gender role attitudes can help us to understand the differential relation of spousal support (emotional and instrumental) to marital quality (i.e., marital satisfaction and marital conflict) in married/cohabitating men and women. Marital conflict (i.e., disagreement or tension with one’s spouse) is often strongly related to marital satisfaction (e.g., Koren, Carlton, & Shaw, 1980); as a result, both outcomes were included as measures of marital quality in the present study. Based on previous research, it was predicted that men and women would significantly differ in their gender role attitudes, spousal support, marital satisfaction, and marital conflict. Specifically, women would endorse greater egalitarian attitudes, report less emotional and instrumental support from their spouse, report more marital conflict, and be less satisfied than men with their marriages (Hypothesis 1). We also predicted that gender role attitudes would be differentially related to spousal support and marital quality for married men and women. For women, egalitarian attitudes would be positively related to instrumental spousal support and marital conflict, but negatively related to emotional spousal support and martial satisfaction (Hypothesis 2). For men, the opposite predictions were made; in other words, egalitarian attitudes would be positively related to marital satisfaction and emotional spousal support and negatively related to marital conflict and instrumental spousal support (Hypothesis 3). Although we acknowledge that a spouse’s gender role attitudes would play a significant role, we argue that an individual’s own gender role attitudes will also be related to reports of instrumental spousal support. Regardless of the spouse’s gender role attitudes, egalitarian women expect their spouses to share the housework, whereas traditional women do not (and the reverse would be true for egalitarian and traditional men’s support expectations). Furthermore, if we assume that concordance of gender role attitudes among spouses is more common than discordance (Kulik, 2004), an individual’s support expectations should correlate with his/her spouse’s willingness to behave in ways similar to the individual’s expectations.

Finally, our main hypothesis was that gender role attitudes and gender would interact in the link between spousal support and marital quality. This hypothesis is based on the argument that gender role attitudes impact support expectations with respect to different marital domains (e.g., instrumental and emotional support), and, thus, the amount of support received in the specific domain would be related to both marital satisfaction and marital conflict. Specifically, we hypothesized that both emotional and instrumental spousal support would be significant predictors of marital quality (i.e., more marital satisfaction and less marital conflict) for egalitarian women and traditional men. On the other hand, we predicted that only emotional spousal support would significantly predict marital quality for egalitarian men and traditional women (Hypothesis 4).

Methods

Sample

The hypotheses were examined by secondary analyses of data from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS; Kessler et al., 1994), a nationwide household survey of the U.S. population aged 15–54 years. The NCS was designed to produce data on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and their correlates, and was based on a stratified, multistage area probability sample of the non-institutionalized civilian population in the 48 coterminous U.S. states. The 8098 respondents who participated in the NCS were selected using probability methods (response rate was 82.4%).

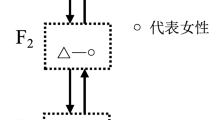

The data were weighted to adjust for the differential probabilities of selection across and within the U.S. households. The data were post-stratified to approximate the national population distributions of age, sex, race-ethnicity, marital status, education, living arrangements, region, and urbanicity, as defined by the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS; U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1992). A comparison of the NCS sample data with the NHIS shows that this sample is quite comparable to the general adult population of the United States. For example, the percentage of men (49.8%) and women (50.2%) in the NCS is equivalent to the national population (49.1 and 50.9%, respectively). Similarly equivalent percentages were found for age, marital status, race, education, region, and urbanicity. See Kessler et al. (1994) for more details on the NCS sample. For the present analyses, only data from those respondents who completed both parts of the interview, who were married or cohabitating, and who had complete data on the study variables were used in analyses. This sub-sample (n = 3500) is comprised of 1787 women (51.06%) and 1713 men (48.94%).

Measures

Sociodemographics

Seven demographic characteristics that were believed to be related to one or more of the major study variables were assessed: age, education, income, urbanicity, race/ethnicity, region, and number of children. Age range in this subsample was from 16 to 54 years and was represented as a continuous variable. Education was a continuous variable that consisted of the number of completed years of formal education. Income was also a continuous variable that represented total family income before taxes in the year prior to the interview. Urbanicity refers to the size of the population where a person lived: major metropolitan (1,000,000 or more people), other urban/suburban (less than 1,000,000 but greater than 20,000 people), and rural (less than 20,000). Race/ethnicity was self-identified and consisted of European Americans, African Americans, Hispanics, and Other races/ethnicities. Region refers to the region of United States in which respondents lived: Northeast, South, Midwest, and West. Finally, number of children was a continuous variable that represented the total number of children who ranged in age between 0 and 19 years, whom the respondent is helping to raise. Race/ethnicity, urbanicity, and region categories were represented using dichotomous variables, with European Americans, metropolitan, and Midwest chosen as the reference groups. Table 1 provides information regarding the demographic characteristics of the married/cohabitating sample used for the present analyses.

Gender Role Attitudes

Gender role attitudes were assessed in the NCS with six items (e.g., “It is much better for everyone if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of home and family”; “Most of the important decisions for the family should be made by the man of the house”; “Husbands and wives should evenly divide household chores like cooking and cleaning”). Respondents rated their level of agreement for each item on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all; 4 = a lot). Items were recoded to all be in the same direction, such that higher scores indicate stronger egalitarian gender attitudes. A sum score on the six items was calculated (α = .73).

Spousal Support

Assessment of emotional spousal support in the NCS was based on a measure previously developed by Schuster et al. (1990). Emotional spousal support was measured with six items (e.g., “How much does your spouse/partner really care about you?”), which respondents rated on 4-point Likert scales (1 = not at all; 4 = a lot). The mean was calculated for the scores on the six items (α = .83). Instrumental spousal support was assessed in the NCS with two items: 1) “Who spends more time taking care of responsibilities at home-you or your (husband/wife/partner)?” was rated on a 7-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 = respondent does a lot more; 4 = both equal; 7 = spouse does a lot more); and 2) “How willing is your husband/wife/partner to help you at home when you are tired after a demanding day?” was rated on a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 = not at all; 4 = very). The two items were summed such that higher scores indicate greater instrumental spousal support. Instrumental spousal support was moderately correlated with emotional spousal support, r = .29, p < .001. Cronbach’s alpha for the instrumental spousal support measure was .52. Although this reliability is low, it is not unexpected given the different rating scales for the items (which weights the first item more heavily than the second item) and the abbreviated test length. Using Nunnally’s (1970) correction for test length, a 6-item measure of instrumental spousal support with the same average correlation among items would achieve an acceptable reliability of .76.

Marital Quality

Both marital satisfaction and marital conflict were assessed in the NCS. Marital satisfaction was measured with one item on a 4-point Likert scale: “Overall, would you rate your (marriage/relationship) as excellent, good, fair or poor?” Scores were reversed so that a higher score indicates greater marital satisfaction. Marital conflict in the NCS was based on a measure previously developed by Schuster et al. (1990) and was assessed with six items (e.g., “How often does your spouse/partner make too many demands on you?”), which respondents rated on 4-point Likert scales (1 = never; 4 = often). The mean was calculated for the scores on the six items (α = .81). The two areas of marital quality were strongly correlated with each other, r = −.53, p < .001.

Overview of Analyses

Given that each scale used a different metric and the weighting of the data was complex, all scale scores were standardized prior to analysis. To determine potential control variables, a series of multiple regression analyses were conducted to determine whether the sociodemographic variables predicted any of the major study variables. Based on the results of those analyses, the following sociodemographic variables were retained as control variables in all analyses: age, education, income, number of children, race, urbanicity, and region. Finally, whenever the total sample was analyzed, respondent gender was included as a control variable. Descriptive statistics were next calculated for the major study variables, followed with a comparison by respondent gender.

To test our hypotheses, multiple linear regression analysis was first used to examine the relation between gender role attitudes and spousal support and marital quality for the entire sample, and then stratified by respondent gender. Next, stratified multiple linear regression analyses were utilized to examine the complex relations between gender, gender role attitudes, spousal support and marital quality. Finally, as a result of the complex sample design and weighting, estimates of standard errors were obtained using the method of Jackknife Repeated Replication (Rust, 1985). A SAS macro was used to implement this procedure by computing estimates in each of 42 subsample pseudoreplicates and manipulating these estimates to arrive at design-based standard errors. These estimates take into account both the clustering and weighting in the study’s design.

Results

Gender Differences in Gender Role Attitudes, Spousal Support, and Well-Being

The first hypothesis predicted that men and women would differ significantly on the major study variables, such that women would report greater egalitarian attitudes, less emotional and instrumental spousal support, less marital satisfaction, and greater marital conflict than men would. A MANCOVA was conducted with gender role attitudes, emotional and instrumental spousal support, and marital satisfaction and conflict as the dependent variables and respondent gender as the independent variable (controlling for age, education, income, race/ethnicity, region, and urbanicity). The multivariate test for respondent gender was significant, F (5, 2487) = 414.37, p < .001. As shown in Table 2, when the dependent variables were tested separately using a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of .01, men and women significantly differed on all of the variables in the predicted directions.

Gender Role Attitudes on Spousal Support and Marital Quality

We also predicted that gender role attitudes would be differentially related to spousal support and marital quality for women and men (Hypotheses 2 and 3). In order to test these hypotheses, the main effects of gender and gender role attitudes were entered simultaneously into a multiple linear regression analyses, after controlling for the sociodemographic variables. Next, the interaction term of gender (0 = men; 1 = women) and gender role attitudes was entered into the model. Finally, the analyses were stratified by respondent gender. The two-way interaction between respondent gender and gender role attitudes was significant for all four variables: 1) emotional spousal support, b = −.10, se = .04, p < .01; 2) instrumental spousal support, b = .09, se = .03,p < .01; 3) marital satisfaction, b = −.16, se = .04, p < .001; and, 4) marital conflict, b = .08, se = .04, p < .05. Analyses stratified by respondent gender showed that, as predicted, women’s egalitarian attitudes were negatively related to emotional spousal support and marital satisfaction and positively related to marital conflict and instrumental spousal support (albeit not significantly for instrumental support). On the other hand, men’s egalitarian attitudes were positively related to emotional spousal support and marital satisfaction and negatively related to marital conflict and instrumental support (albeit not significantly for emotional support or marital conflict). See Table 3.

Moderating Role of Gender and Gender Role Attitudes on Spousal Support and Marital Quality

To test Hypothesis 4, that gender role attitudes and respondent gender combine to influence the relationship between spousal support and marital quality, we analyzed a subsample of men and women whom we classified as distinctly traditional or egalitarian. Specifically, gender role attitudes were dichotomized by taking the lowest and highest quartile scores to create traditional and egalitarian groups, respectively, (i.e., traditional men, egalitarian men, traditional women, and egalitarian women). This decision was based on our belief that these groups of individuals would show the strongest differences in the relation between spousal support and martial quality—as opposed to those individuals who endorsed a combination of traditional and egalitarian attitudes. As a result, the following analyses were conducted on approximately one-half of the sample (n = 1,729). In these stratified analyses, the two aspects of spousal support (emotional and instrumental) were simultaneously entered into regressions to predict marital satisfaction and marital conflict, after controlling for the sociodemographic variables. Results will be presented first for marital satisfaction and then for marital conflict.

As shown in Table 4, results of the stratified analyses indicate that different dimensions of spousal support were related to marital satisfaction based on gender role attitudes and respondent gender. In support of our hypothesis, both emotional and instrumental spousal support were significant predictors of greater marital satisfaction for egalitarian women and traditional men, whereas only emotional spousal support was a significant predictor of greater marital satisfaction for traditional women and egalitarian men.

Table 5 presents the results for marital conflict; the stratified analyses showed results similar to those for marital satisfaction. Specifically, both emotional and instrumental spousal support were significant predictors of less marital conflict for egalitarian women; however, contrary to predictions, only emotional spousal support was a significant predictor of less marital conflict for traditional men. Finally, as predicted, only emotional spousal support was significantly related to less marital conflict for both traditional women and egalitarian men.

Discussion

Although researchers have examined gender role attitudes and marital quality, most of their work has focused on the division of household labor and ignored the role of emotional spousal support. Furthermore, relatively little is known about the connection between spousal support and marital quality, especially within the context of gender (see Acitelli, 1996, for a review). Our study was the first to examine (in a nationally representative sample of married/cohabitating adults) whether gender role attitudes would explain the differential role of spousal support in marital satisfaction and conflict for men and women. Our results show several interesting patterns. First, although men and women differed in the predicted directions on gender role attitudes, spousal support, and marital quality, these simple gender differences do not reveal the full picture. Rather, gender role attitudes, in conjunction with respondent gender, were needed to differentiate the role of spousal support in marital quality.

As evidence of the importance of within group differences, gender role attitudes were differentially related to both spousal support and marital quality for both men and women. Consistent with prior research, egalitarian attitudes were related to better marital quality for men, but lower marital quality and less emotional spousal support for women. It was interesting, but not unexpected, that egalitarian attitudes were related to less instrumental spousal support for men. However, egalitarian attitudes were not significantly related to instrumental spousal support for women or to emotional spousal support for men. Why would gender role attitudes be unrelated to these spousal support perceptions? With respect to instrumental support, as discussed earlier, an ideology of gender equality does not necessarily translate into marital equality. Even though studies show that as men become more egalitarian in their beliefs they are more likely to share in household labor (Perry-Jenkins & Crouter, 1990; Pyke & Coltrane, 1996), Greenstein (1996) found that men do relatively little housework unless both they and their wives are relatively egalitarian in their beliefs about gender and marital roles. In addition, wives are more likely than husbands to do more of the housework on days when their spouse had a stressful day at work (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Wethington, 1989). Thus, regardless of gender role attitudes, the reality is that wives are still doing the majority of the household labor. With respect to emotional support, because men are more likely to rely on their wives for emotional support than the reverse (Belle, 1987), gender role attitudes may not influence this perception. In other words, whether egalitarian or traditional, men tend to view their wives as their sole confidants.

The heart of our findings concerns the intertwining of respondent gender and gender role attitudes in the link between spousal support and marital quality. As predicted, both emotional and instrumental spousal support were significant predictors of marital quality for traditional men and egalitarian women, whereas only emotional spousal support was a significant predictor of marital quality for egalitarian men and traditional women. These results taken together suggest that the fulfillment of emotional support needs appear to be of primary importance for traditional women’s and egalitarian men’s perceptions of the marital relationship. On the other hand, it is a combination of emotional and instrumental support needs that are considered when traditional men and egalitarian women evaluate the quality of their marital relationship. Our results provide preliminary evidence for our idea that not only is the fulfillment of support needs by one’s spouse important for marital quality, but it is also domain specific depending on an individual’s gender and gender role attitudes. This interpretation is supported by the argument that “contextual variables [such as gender] can affect the meaning of perceptions and behaviors in marriage” (Acitelli, 1996, p.90). Although Acitelli (1996) considered gender as one context, she only briefly discussed gender role attitudes as a potential explanation of gender differences in social support and never considered within gender differences in these attitudes. Aside from marriage, researchers have recently begun to examine the interaction of gender and gender role attitudes in understanding other aspects of relationships, such as intimate partner aggression (Fitzpatrick, Salgado, Suvak, L. A. King & D. W. King, 2004).

One implication of the present study for future research is the need to expand work on the intersection of gender and gender role attitudes in marital quality. For instance, the idea of perceived fairness has received quite a bit of attention in relationship research recently. Grote and Clark (2001) found that perceived fairness in the division of household labor is important in understanding marital satisfaction longitudinally. As perceived fairness may be closely tied to support expectations, it would be worthwhile to examine how both of these factors may explain the relationships found in the present study. One issue that may be strongly connected with perceived fairness is whether the wife is employed or is a homemaker. In fact, prior researchers have divided women into employed wives and homemaker/unemployed wives (Erickson, 1993; Vanfossen, 1981)—ostensibly as a measure of egalitarian versus traditional gender role attitudes. However, post hoc analyses of the current dataset showed that, when traditional and egalitarian groups were created based on whether the wife was employed or not, the results indicated only a between-gender difference or no difference at all. Hence, simply knowing whether the wife works outside of the home may not be sufficient to understand the function of gender role attitudes in spousal support and marital quality, or to understand the potential mechanisms involved in this relation.

Because the present sample consisted only of married/cohabitating individuals, it would also be fruitful to examine these issues in married/cohabitating couples (Acitelli, 1996). As suggested by Pasley, Kerpelman and Guilbert (2001), one important issue to address is the concordance or discordance of gender role attitudes within a couple. The findings from the present study naturally lead to the question of what happens when each spouse holds a different notion of what is expected in the marriage. Huston and Geis (1993) reported that husbands and wives typically bring a mixture of gender-related attitudes and beliefs to a marriage that, in turn, affect behavioral patterns in that marriage. For example, if one spouse is egalitarian and one spouse is traditional, it is not possible for both to be satisfied with the division of household labor, which could lead to worse marital quality. Over the past 20 years, researchers have consistently found that discordance of gender role attitudes is related to less marital satisfaction for both men and women (e.g., Bowen & Orthner, 1983; Cooper, Chassin, & Zeiss, 1985; Li & Caldwell, 1987; Lye & Biblarz, 1993; Sanchez & Gager, 2000). We were surprised to find that no published study to date has focused on gender role attitude concordance in the link between spousal support and marital quality. Future research on these issues may benefit more from an examination of whether a husband’s and wife’s gender role attitudes match or not, rather than whether the individuals are traditional or egalitarian.

Limitations

Several caveats regarding the present study are in order. First, this study involves secondary analyses of data previously collected as part of a large national sample. Consequently, we had to take advantage of the measures that were included in that study to test our hypotheses, and those measures do not always provide exact operationalizations of our constructs. For example, the marital satisfaction measure consisted of only one item. However, researchers have found that a single item measure of marital quality is often as good a predictor as multiple item measures (Sharpley & Cross, 1982). Other dataset limitations include the limited scale of instrumental spousal support—a more complete measure of the division of household labor would be desirable and more reliable. The dataset also omitted other potentially relevant domains of spousal support (e.g., support expectations). In addition, the gender role attitudes scale was limited in scope; a more complete assessment of gender role attitudes is needed to replicate the results. Finally, the data are correlational, and hence we cannot determine whether spousal support and marital quality have a unidirectional or bidirectional relation with each other. Despite these limitations, the major strength of this dataset is its generalizability, as it is representative of the adult U.S. population. Also, the results found with the abbreviated measures suggest that the true associations may simply be attenuated from those found with more complete measures.

Conclusion

In the present study, we not only replicated previous research on gender role attitudes and marital quality, we extended the theoretical perspective of gender role attitudes by examining whether within gender differences can explicate the role of spousal support in both marital satisfaction and conflict. Secondary data analyses of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults showed that the intersection of respondent gender and gender role attitudes helped to explain the link between spousal support and marital quality. Specifically, both emotional and instrumental support were predictive of marital quality for egalitarian women and traditional men, whereas only emotional support was predictive of marital quality for traditional women and egalitarian men. Overall, these results suggest that it is important to know not only an individual’s gender, but also his or her gender role attitudes, if we want to understand how spousal support is related to marital quality.

References

Acitelli, L. K. (1996). The neglected links between marital support and marital satisfaction. In G. R. Pierce, B. R. Sarason, & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Handbook of social support and the family (pp. 83–103). New York: Plenum.

Acitelli, L. K., & Antonucci, T. C. (1994). Gender differences in the link between marital support and satisfaction in older couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 688–698.

Amato, P. R., & Booth, A. (1995). Changes in gender role attitudes and perceived marital quality. American Sociological Review, 60, 58–66.

Ashmore, R. D. (1990). Sex, gender, and the individual. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 486–526). New York: Guilford.

Bartley, S. J., Blanton, P. W., & Gilliard, J. L. (2005). Husbands and wives in dual-earner marriages: Decision-making, gender role attitudes, division of household labor, and equity. Marriage and Family Review, 37, 69–94.

Belle, D. (1987). Gender differences in the social moderators of stress. In R. C. Barnett, L. Biener, & G. K. Baruch (Eds.), Gender and stress (pp. 257–277). New York: Free.

Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces, 79, 191–228.

Blaisure, K. R., & Allen, K. R. (1995). Feminists and the ideology and practice of marital equality. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57, 5–19.

Bolger, N., DeLongis, A., Kessler, R. C., & Wethington, E. (1989). The contagion of stress across multiple roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51, 175–183.

Botkin, D. R., Weeks, M. O., & Morris, J. E. (2000). Changing marriage role expectations: 1961–1996. Sex Roles, 42, 933–942.

Bowen, G. L., & Orthner, D. K. (1983). Sex-role congruency and marital quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 223–230.

Buunk, B. P., Kluwer, E. S., Schuurman, M. K., & Siero, F. W. (2000). The division of labor among egalitarian and traditional women: Differences in discontent, social comparison, and false consensus. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 759–779.

Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1208–1233.

Cooper, K., Chassin, L. A., & Zeiss, A. (1985). The relation of sex-role self-concept and sex-role attitudes to the marital satisfaction and personal adjustment of dual-worker couples with preschool children. Sex Roles, 12, 227–241.

Davis, S. N., & Greenstein, T. N. (2004). Cross-national variations in the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1260–1271.

Erickson, R. J. (1993). Reconceptualizing family work: The effect of emotion work on perceptions of marital quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 888–900.

Fan, P., & Marini, M. M. (2000). Influences on gender-role attitudes during the transition to adulthood. Social Science Research, 29, 258–283.

Fitzpatrick, M. K., Salgado, D. M., Suvak, M. K., King, L. A., & King, D. W. (2004). Associations of gender and gender role ideology with behavioral and attitudinal features of intimate partner aggression. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 5, 91–102.

Gove, W. R. (1973). Sex, marital status, and mortality. American Journal of Sociology, 79, 45–67.

Greenstein, T. N. (1996). Husbands’ participation in domestic labor: Interactive effects of wives’ and husbands’ gender ideologies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 585–595.

Grote, N. K., & Clark, M. S. (2001). Perceiving unfairness in the family: Cause or consequence of marital distress? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 281–293.

Hackel, L. S., & Ruble, D. N. (1992). Changes in the marital relationship after the first baby is born: Predicting the impact of expectancy disconfirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 944–957.

Helmreich, R. L., Spence, J. T., & Gibson, R. H. (1982). Sex-role attitudes: 1972–1980. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 8, 656–663.

Hochschild, A. R., & Machung, A. (1989). The second shift. New York: Avon Books.

Husaini, B. A., Neff, J. A., Newbrough, J. R., & Moore, M. C. (1982). The stress-buffering role of social support and personal competence among the rural married. Journal of Community Psychology, 10, 409–426.

Huston, T. L., & Geis, G. (1993). In what ways do gender-related attributes and beliefs affect marriage? Journal of Social Issues, 49, 87–106.

Kessler, R. C., McGonagle, K. A., Zhao, S., Nelson, C. B., Hughes, M., Eshleman, S., et al. (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 8–19.

King, L. A., & King, D. W. (1985). Sex-role egalitarianism: Biographical and personality correlates. Psychological Reports, 57, 787–792.

Koren, P., Carlton, K., & Shaw, D. (1980). Marital conflict: Relations among behaviors, outcomes, and distress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 48, 460–468.

Kulik, L. (2004). Predicting gender role ideology among husbands and wives in Israel: A comparative analysis. Sex Roles, 51, 575–587.

Larsen, K. S., & Long, E. (1988). Attitudes toward sex roles: Traditional or egalitarian? Sex Roles, 19, 1–12.

Li, J. T., & Caldwell, R. A. (1987). Magnitude and directional effects of marital sex-role incongruence on marital adjustment. Journal of Family Issues, 8, 97–110.

Lye, D. N., & Biblarz, T. J. (1993). The effects of attitudes toward family life and gender roles on marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Issues, 14, 157–188.

McGonagle, K. A., Kessler, R. C., & Schilling, E. A. (1992). The frequency and determinants of marital disagreements in a community sample. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9, 507–524.

Noor, N. M. (1997). The relationship between wives’ estimates of time spent doing housework, support, and wives’ well-being. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 7, 413–423.

Nunnally, J. C. (1970). Introduction to Psychological Measurement (pp. 262–264). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pasley, K., Kerpelman, J., & Guilbert, D. E. (2001). Gendered conflict, identity disruption, and marital instability: Expanding Gottman’s model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18, 5–27.

Perry-Jenkins, M., & Crouter, A. C. (1990). Men’s provider-role attitudes: Implications for household work and marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Issues, 11, 136–156.

Pleck, J. H. (1985). Working wives/working husbands. Beverly Hills, California: Sage.

Pyke, K., & Coltrane, S. (1996). Entitlement, obligation, and gratitude in family work. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 60–82.

Ross, C. E. (1987). The division of labor at home. Social Forces, 65, 816–833.

Rust, K. (1985). Variance estimation for complex estimators in sample surveys. Journal of Official Statistics, 1, 381–397.

Sanchez, L., & Gager, C. T. (2000). Hard living, perceived entitlement to a great marriage, and marital dissolution. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 708–722.

Schuster, T., Kessler, R. C., & Aseltine, R. H., Jr. (1990). Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18, 423–437.

Sharpley, C. F., & Cross, D. G. (1982). A psychometric evaluation of the Spanier Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44, 739–747.

Solomon, L. J., & Rothblum, E. D. (1986). Stress, coping, and social support in women. Behavior Therapist, 9, 199–204.

Thompson, L. (1993). Conceptualizing gender in marriage: The case of marital care. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 557–569.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1992). National Health Interview Survey, 1989 (Computer file). Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics.

Vanfossen, B. E. (1981). Sex differences in the mental health effects of spouse support and equity. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 130–143.

Vinokur, A. D., & Vinokur-Kaplan, D. (1990). “In sickness and in health”: Patterns of social support and undermining in older married couples. Journal of Aging and Health, 2, 215–241.

Voydanoff, P., & Donnelly, B. W. (1999). The intersection of time in activities and perceived unfairness in relation to psychological distress and marital quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 739–751.

Williams, D. G. (1988). Gender, marriage, and psychological well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 9, 452–468.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nancy Grote for her comments on an earlier draft, and Heidi Bissell for her assistance on preliminary analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mickelson, K.D., Claffey, S.T. & Williams, S.L. The Moderating Role of Gender and Gender Role Attitudes on the Link Between Spousal Support and Marital Quality. Sex Roles 55, 73–82 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9061-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9061-8