Abstract

This article reports on the psychometric properties of The Recalled Childhood Gender Identity/Gender Role Questionnaire, a 23-item questionnaire designed to measure recalled gender-typed behavior and relative closeness to mother and father during childhood. Five considerations guided its development: (1) scale items should show, on average, evidence for “normative” sex differences or be related to within-sex variation across target groups for which one might expect, on theoretical grounds, significant differences; (2) the items should be written in a manner such that they could be answered by both men and women; (3) the items should provide coverage of a range of gender-typed behaviors, including those that capture core aspects of the phenomenology of gender identity disorder in children; (4) the items should be abstract enough such that the description of the underlying construct would not be tied to a specific object or activity that might have been common during one period of time but not another, thus affording greater ecological validity across a large age range and birth cohorts; and (5) the questionnaire should be short enough that it would have practical utility in broader research projects and in clinical settings. A total of 1305 adolescents and adults (735 girls/women; 570 boys/men), with a mean age of 33.2 years (range=13–74), completed the questionnaire. Factor analysis identified a two-factor solution: Factor 1 consisted of 18 items that pertain to childhood gender role and gender identity, which accounted for 37.4% of the variance, and Factor 2 consisted of three items that pertain to parent–child relations (closeness to mother and father), which accounted for 7.8% of the variance. Tests of discriminant validity were generally successful in identifying significant between-group variation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over the past 40 years or so, psychosexual differentiation has been studied with regard to at least three parameters: gender identity, gender role, and sexual orientation. Gender identity has been defined as a person’s basic sense of self with regard to “maleness” and “femaleness” (Stoller, 1965, 1968). As noted by Collaer and Hines (1995), most biological males have a “male” gender identity and most biological females have a “female” gender identity. In the clinical literature, a person’s “discontent” or unhappiness about being male or female has been characterized by the term “gender dysphoria” (Fisk, 1973). Gender role has been defined in various ways; for example, it has included a person’s preference for, or adoption of, behavioral characteristics or endorsement of personality traits that are linked to cultural notions of masculinity and femininity. In childhood, gender role has been commonly indexed and operationalized with regard to several parameters, including peer preferences, toy interests, roles in fantasy play, dress-up play, and so on (Ruble & Martin, 1998). The extent to which a child identifies with, or feels closer to, the parent of the same or the other sex may also be an indicator of gender identity and gender role identification. Like gender identity, gender role behaviors are also, on average, sex-dimorphic (Collaer & Hines, 1995; Zucker, 2005a). Lastly, sexual orientation can be defined with regard to a person’s sexual attraction and arousal pattern. When sexual orientation is not complicated by a paraphilic sexual arousal pattern, it is typically trichotomized simply as heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual. Sexual orientation is also strongly sex-dimorphic; the vast majority of biological males are predominantly attracted sexually to females, and the vast majority of biological females are predominantly attracted sexually to males (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994).

Over the years, various assessment tools have been developed to measure both gender identity and gender role in children (Ruble & Martin, 1998; Zucker, 1992; Zucker et al., 1993). In adolescents and adults, the measurement of gender identity has received less attention, although some efforts have been made to operationalize gender dysphoria, in both clinical and nonclinical populations (Cohen-Kettenis & van Goozen, 1997; Deogracias et al., 2005; Docter & Fleming, 1992, 2001). In contrast, gender role has been studied more extensively and operationalized with regard to several parameters, including endorsement of putatively sex-dimorphic personality attributes (Bem, 1974; Spence & Helmreich, 1978; Willemsen & Fischer, 1999), activity interests (Berenbaum, 1999), occupational preferences (see e.g., Brown, 1982; Lippa, 1998), and gender “types” (Vonk & Ashmore, 2003) (for a review, see Lippa, 2001).

In a large number of studies of adults, researchers have attempted to measure retrospectively recalled patterns of childhood gender identity and gender role. This line of research has been carried out in the context of comparisons of the developmental histories of heterosexual and homosexual adults, adults with gender identity disorder (GID) and control participants, and adults with various physical intersex conditions, such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and control participants.

The largest body of this literature consists of retrospective comparative studies of heterosexual and homosexual adults, which was subjected to a meta-analysis by Bailey and Zucker (1995). In a quantitative review, they examined 41 studies, which yielded 48 independent effect sizes: 32 compared heterosexual and homosexual men, and 16 compared heterosexual and lesbian women. Bailey and Zucker reported that, on average, there were substantial differences in patterns of recalled gender identity/gender role between heterosexual and homosexual adults. Both homosexual men and women recalled more cross-gender-typed behavior during childhood than did their heterosexual counterparts (respective d’s were 1.31 and 0.96.). Indeed, every single study that was examined showed a significant effect between heterosexual and homosexual adults. Frequency distributions were available for seven male samples and five female samples who were given multiitem scales. For the male samples, 89% of homosexual men exceeded the median of heterosexual men (i.e., indicated more recalled cross-gender behavior), and only 2% of heterosexual men exceeded the median of homosexual men. There was slightly more overlap for women—81% of lesbians exceeded the median of heterosexual women, and only 12% of heterosexual women exceeded the median of lesbians. Subsequent to the Bailey and Zucker (1995) meta-analysis, similar findings have been reported (Bailey, Dunne, & Martin, 2000; Bailey & Oberschneider, 1997; Bogaert, 2003; Cohen, 2002; Dunne, Bailey, Kirk, & Martin, 2000; Grossmann, 2002; Loehlin & McFadden, 2002; Phillips & Over, 1995; Purcell, 1995; Safir, Rosenmann, & Kloner, 2003; Strong, Singh, & Randall, 2000; Tortorice, 2002; Whitam, Daskalos, Sobolewski, & Padilla, 1998) and, to our knowledge, there has been no null finding.

Thus, the recalled measurement of childhood gender-typed behavior has shown significant and substantial variation between heterosexual and homosexual adults. In other studies along this line, researchers have attempted to identify similar variations, as in comparisons of adults with various types of physical intersex conditions and controls (Dittmann et al., 1990; Hines, Ahmed, & Hughes, 2003) or of adults with GID and controls (Freund, Langevin, Satterberg, & Steiner, 1977).

Bailey and Zucker (1995) noted that there was a great deal of variability in measurement approaches: in some studies, single-item scales were used (n=17), and in others multiitem scales were used (n=31). It is not surprising that the latter showed stronger effects. Apart from this technical psychometric issue, there are other constraints to the available measures: some were developed for use only with biological males (Hockenberry & Billingham, 1987) whereas others were developed for use only with biological females (Blanchard & Freund, 1983). The content and coverage of the items also varied; for example, some instruments/measures included toy and activity interests or peer affiliation preference, but others did not (see Bailey & Zucker, 1995, Table 3).

The aim of the present study was to develop a contemporary measure of recalled childhood gender identity and gender role. Five considerations guided its development: (1) scale items should show, on average, evidence for “expected” sex differences or be related to within-sex variation across target groups for which one might expect, on theoretical grounds, significant differences (see e.g., Chivers & Bailey, 2000; Singh, Vidaurri, Zambarano, & Dabbs, 1999; Strong et al., 2000; Taywaditep, 2001; Tortorice, 2002; see also Beard, & Bakeman, 2000; Landolt, Bartholomew, Saffrey, Oram, & Perlman, 2004); (2) the items should be written in a manner such that they could be answered by both men and women; (3) the items should provide coverage of a range of gender-typed behaviors, including those that capture core aspects of the phenomenology of GID in children (American Psychiatric Association, 2000); (4) the items should be abstract enough such that the description of the underlying construct would not be tied to a specific object or activity that might have been common during one period of time but not another, thus affording greater ecological validity across a large age range and birth cohorts; and (5) the questionnaire should be short enough that it would have practical utility in broader research projects and in clinical settings.

Method

Participants

The initial sample consisted of 110 women and 109 men, unselected for gender identity or sexual orientation, primarily of a middle-class background, the majority of whom were either students or employees at a university. The mean age of the sample was 34.2 years (SD=14.6; range, 16–74), with no significant sex difference in age (t < 1). This sample was used to verify the presence of significant sex differences for those items on the questionnaire for which such a difference would be predicted based on the previous empirical literature. Data from this sample were obtained in 1990.

Subsequent to this initial sample, the questionnaire was administered to an additional 1086 adolescents and adults (625 girls/women; 461 boys/men) between 1990 and 2003. Table 1 provides a description of the different types of individuals who comprised this larger sample. Some of these individuals were participants in specific research studies, whereas others completed the questionnaire as part of either their own or their child’s clinical assessment in the Child and Adolescent Gender Identity Clinic, which is housed within the Child, Youth, and Family Program, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Ontario.

Measure

The initial sample of 219 adults completed a 22-item questionnaire that pertained to childhood gender identity, gender role, and feelings about one’s parents. Participants were instructed to answer questions “… about your behavior as a child, that is, the years ‘0 to 12.’ For each question, circle the response that most accurately describes your behavior as a child. Please note that there are no ‘right or wrong’ answers. ” Twenty-one items were rated on a 5-point response scale, and one was rated on a 4-point response scale. For some items, however, an additional response option allowed the participant to indicate that the behavior did not apply (e.g., for the question about favorite playmates, there was the option “I did not play with other children”). After data on this sample were collected, one additional item (Item 20 in the Appendix) was added to the questionnaire. The Appendix shows the final 23-item questionnaire (versions for males and females).

Results

Sex differences

Table 2 shows the mean and SD for each item as a function of sex, based on the initial sample of 219 adults. For Items 1–3, 7–10, and 14, a higher value reflects a putatively female-typical response, and a lower score reflects a putatively male-typical response, whereas for Items 5–6 and 15 a higher value reflects a putatively male-typical response, and a lower score reflects a putatively female-typical response. All 11 items yielded significant sex differences in the expected direction (all p’s < .001). Cohen’s d (M 1−M 2/SD pooled) was calculated and it can be seen in Table 2 that the effect sizes were “large” (Cohen, 1988).

Items 4, 11–13, and 18–20 were written in a manner that reflected degree of conventionality or “normality” (e.g., how good one felt about being a boy or a girl), and thus were not intended to elicit sex differences, but could, theoretically, yield within-sex differences as a function of some other marker variable, such as gender identity or sexual orientation in adulthood. For these seven items, a lower score reflects a putatively conventional or “typical” response. Four items yielded a significant sex difference; men recalled a stronger pattern of conventionality than women did (see Table 2). For these items, the effect sizes were much smaller, as would be expected (see Table 2).

Items 16–17 and 21–22 pertained to parent–child relations. It was predicted that the men would recall feeling somewhat closer emotionally to their fathers and women would recall feeling somewhat closer emotionally to their mothers (Item 16), but the sex difference was not significant. There was also no significant sex difference in relative admiration of mother and father (Item 17). Regarding recalled felt perception of parental care, men recalled that their mothers cared about them significantly more than the women did (Item 21), but there was no sex difference in recalled paternal care (Item 22).

Factor analysis

Prior to performing factor analysis, the responses to the mother-care item (Item 21 in Table 2) and the responses to the father-care item (Item 22 in Table 2) were subtracted to create a difference score to reflect the degree to which there was, or was not, a skew in perceived parental care (e.g., “always felt that my mother cared about me,” but “never felt that my father care about me”). Thus, the difference score could range from −4 to +4. For the factor analysis, all other items were scored in a manner such that a higher score indicated a sex-typical or “conventional” response. If a participant indicated that a specific item did not apply (Option “f” for Items 1–3, 6–10, 12–14, 16, 19, 22–23; see Appendix), it was treated as a missing value.

As recommended by Comrey (1978), preliminary analyses evaluated the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .93, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at p < .00001, which indicate the suitability of the data for factor analytic procedures.

A principal axis factor analysis with varimax rotation was performed on the questionnaire items for all 1305 participants. In order to retain data from participants for whom Option “f” was endorsed for one or more of the items noted above, pairwise deletion was used. Four factor solutions were explored: an unrestricted factor extraction, a forced one-factor solution, a forced two-factor solution (gender identity/gender role and parental identification/closeness), and a forced three-factor solution (gender identity, gender role, and parental identification/closeness). These solutions were examined for women and men combined, for women only, and for men only.

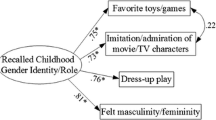

For the women and men combined, the results suggested that a two-factor solution was the best fit to the data: Factor 1 accounted for 37.4% of the total variance, and Factor 2 accounted for 7.8% of the total variance. For Factor 1, corrected item-total correlations ranged from .21 to .76 and Cronbach’s α was .92; for Factor 2, corrected item-total correlations ranged from .50 to .60 and Cronbach’s α was .73.

Table 3 shows the two factors and the items with factor loadings ≥.40. Factor 1, which contained 18 items, clearly indexed gender identity/gender role, and Factor 2, which contained three items, clearly indexed relative identification/emotional closeness with mother and father. For these 21 items, it can be seen in Table 3 that there was no indication of cross-loading. Only one item (Item 13), which pertains to degree of resentment of one’s same-sex sibling (if there was one), did not load on either factor at ≥.40. Table 3 also shows that the factor loadings were very similar when analyzed separately for women and for men.

Discriminant validity

Several data sets within the entire sample were amenable to test the discriminant validity of the scale scores.

Sex differences

For the initial sample of 219 women and men, unselected for gender identity or sexual orientation, a t-test for Factor 1 showed that the men (M, 4.30; SD=.30) recalled a significantly more conventional pattern of gender-typed behavior than the women did (M, 3.59, SD=.49), t(217)=12.71, p < .001. For Factor 2, the women reported a relatively closer relationship to their mothers (M, 2.29, SD=.99) than the men did to their fathers (M, 1.46, SD=.76), t(217)=6.92, p < .001). The effect size for Factor 1 was d=1.74, and for Factor 2 it was d=0.94.

On Factor 1, there was a significant correlation with age for the women, r=.25, p < .01, which indicates that younger women recalled more cross-gender behavior than older women did, but there was no significant correlation with age for men, r=.12. On Factor 2, there was no significant correlation with age either for women, r=−.04, or men, r=−.02.

Heterosexual and homosexual adults

Table 4 shows the data for the heterosexual–homosexual sample of men and women studied by Tkachuk and Zucker (1991). Because the homosexual sample was significantly older than the heterosexual sample and because the heterosexual men had a significantly higher Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R) IQ than the homosexual men, a preliminary analysis was performed with age and PPVT-IQ as covariates. These two demographic variables did not effect the primary analyses.

For Factor 1, a 2 (sex) × 2 (sexual orientation) analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed significant main effects for sex, F(1, 97)=60.6, p < .001, and sexual orientation, F(1, 97)=37.1, p < .001. Women recalled significantly more cross-gender behavior than men did, and homosexual men and women recalled significantly more cross-gender behavior than heterosexual men and women did. For the heterosexual and homosexual men, the effect size was 1.75 and for the heterosexual and lesbian women, the effect size was 1.24.

For Factor 2, there was a significant main effect for sex, F(1, 97)=32.0, p < .001, and a significant sex × sexual orientation interaction, F(1, 97)=4.69, p=.033. Simple effects analysis showed that both the heterosexual and lesbian women recalled relatively closer relationships with their mothers than did heterosexual and homosexual men to their fathers (both p’s < .01). Heterosexual men recalled a relatively closer relationship to their fathers than homosexual men did, but the difference was not significant (p=.136). Lesbians recalled a relatively closer relationship to their mothers than did heterosexual women, but this difference also was not significant (p=.122). For the heterosexual and homosexual men, the effect size was 0.49, and for the heterosexual and lesbian women, the effect size was 0.40.

Women with congenital adrenal hyperplasia versus sisters/female cousins

Table 5 shows the data for women with CAH and their sisters studied by Zucker et al. (1996). For Factor 1, the CAH women recalled significantly more cross-gender behavior than did their sisters, t(44)=2.07, p=.045. There was no significant difference for Factor 2, t < 1. For Factor 1 the effect size was 0.76, and for Factor 2 the effect size was 0.22.

Across both groups on Factor 1, there was no significant correlation with age, r=.09, or PPVT-IQ, r=.18. On Factor 2, age was correlated positively with a relatively closer relationship with mother, r=.31, p < .05, but there was no significant correlation with PPVT-IQ.

Table 6 shows the data for women with CAH as a function of salt-wasting (SW) versus simple virilizing (SV) status. A variety of data suggest that CAH women who are SW are subject to greater prenatal androgenization than are SV women (Zucker et al., 1996). Because the SV women were significantly older than the SW women, a preliminary analysis was performed with age covaried, which proved age to be noncontributory.

For Factor 1, the SW women recalled more cross-gender behavior than did the SV women, t(29)=2.48, p=.019. For Factor 2, the SV women tended to recall a relatively closer relationship to their mothers than did the SW women, t(29)=1.68, p=.103. For Factor 1 the effect size was 0.91, and for Factor 2 the effect size was 0.62.

Mothers of boys with gender identity disorder and mothers of control participants

Table 7 shows the factor scores for mothers of boys with GID compared to mothers of clinical control boys and nonreferred boys. The first 24 GID mothers were in Mitchell’s (1991) study. Preliminary analysis showed that there were no significant differences on the two factor scores between these mothers and the 206 GID mothers who subsequently completed the questionnaire. One-way ANOVAS showed no significant differences between the three groups of mothers on both Factor 1 and Factor 2, both F’s < 1.

Across the three groups of mothers, the Factor 1 score was significantly related to age, r=.16, p < .01, social class, r=.14, p < .02, and marital status, r=−.17, p < .01. Regarding directionality, younger age, lower social class background, and being single, separated, divorced, or remarried was associated with the mothers’ recalled cross-gender behavior. These three demographic variables were not significantly correlated with the Factor 2 score.

Because the three demographic variables were significantly correlated with one another, a multiple regression analysis was performed for the Factor 1 score. Marital status, R 2=.18, p < .01, and age, R 2=.02, p < .01, were significant predictors of the Factor 1 score.

Adolescents with gender identity disorder and those with transvestic fetishism

Table 8 shows the factor scores for clinic-referred adolescents with GID (separately by sex) and adolescent boys with transvestic fetishism (TF) (with or without cooccurring gender dysphoria). Analysis of demographic data showed that there was a significant between-groups difference in age, F(2, 86)=3.68, p=.029, and for parents’ marital status, χ2(2)=6.17, p=.045. There was no group difference in Full-Scale IQ (FSIQ), F < 1.

A preliminary analysis on the factor scores was performed with age and parents’ marital status covaried, which proved to be noncontributory. For Factor 1, a one-way ANOVA for Group (GID boys, GID girls, TF) was significant, F(2, 86)=44.82, p < .001. A Duncan’s multiple range test showed that both the male and female GID adolescents had significantly higher cross-gender scores than did the adolescents with TF (both p’s < .05); in addition, the female GID adolescents had a significantly higher cross-gender score than the male GID adolescents did (p < .05). For the male GID adolescents and the TF adolescents, the effect-size comparison was 1.65; for the female GID adolescents and the TF adolescents, the effect-size comparison was 2.67; for the male and female GID adolescents, the effect-size comparison was 0.73.

For Factor 2, a one-way ANOVA for Group was also significant, F(2, 86)=10.43, p < .001. A Duncan’s multiple range test showed that the female GID adolescents felt closer to their mothers than did the male GID and TF adolescents to their fathers (both p’s < .05); in addition, the TF adolescents tended to feel closer to their fathers than did the male GID adolescents (p < .10). For the male GID adolescents and the TF adolescents, the effect-size comparison was 0.53; for the female GID adolescents and the TF adolescents, the effect-size comparison was 0.62; for the male and female GID adolescents, the effect-size comparison was 1.38.

Across the three groups, the Factor 1 score was significantly related to age, r=‒.21, p < .05, but not with FSIQ, r=.17, or parents’ marital status, r=.02. Older adolescents recalled more cross-gender behavior. These three demographic variables were not significantly correlated with the Factor 2 score.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to develop a contemporary measure of recalled gender-typed behavior during childhood that can be used with both women and men. Its coverage was intended to include some of the more common aspects of childhood gender-typed behavior for which there are well-established mean sex differences and which are used as indicators of GID in children (e.g., toy preferences, fantasy role preferences) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Item analysis from the initial sample of 219 adults showed that significant sex differences were obtained for those items for which such a difference was predicted based on the prior empirical literature. Indeed, all 11 items for which this prediction was made yielded significant sex differences (all p’s < .001), and, by Cohen’s (1998) criteria, the effect sizes were “large.”

The factor analysis for the entire sample identified two factors: Factor 1 contained items that appeared to index the constructs of gender identity and gender role, whereas Factor 2 contained items that pertain to parent–child relations. When the data were analyzed separately for men and women, the factor analyses showed remarkable similarity to the factor analysis for men and women combined. As noted by Comrey (1978) and Nunnally (1978), an important methodological consideration in factor analysis is to have a large sample size (>200 participants) and participant to item ratio (at least 10:1) in order to avoid spurious results. It is likely that the large sample size and participant to item ratio in the present study contributed to the robust nature of the factor analytic findings.

In three separate comparisons (the men and women in the initial sample, in the heterosexual–homosexual sample studied by Tkachuk and Zucker (1991), and in the GID male and female adolescent sample), there was the consistent finding that girls and women recalled significantly more cross-gender behavior than boys and men did. Tests of discriminant validity yielded findings consistent with the previous literature. For example, the comparison of heterosexual and homosexual adults (Tkachuk & Zucker, 1991) yielded a sexual orientation effect for Factor 1 that is consistent with the large body of retrospective studies reviewed by Bailey and Zucker (1995). The comparison of women with CAH and their sisters was also consistent with previous studies (Dittmann et al., 1990). The comparison of mothers of boys with GID and mothers of clinic-referred and nonreferred boys did not, however, lend support to Stoller’s (1968b) hypothesis that mothers of boys with GID were cross-gendered in their behavior during their own childhoods, but was consistent with Green’s (1987) general finding of no difference in recalled cross-gender behavior in his sample of mothers of feminine and control boys. Lastly, the comparative analysis of male and female adolescents with GID and adolescent boys with TF indicated a between-groups difference consistent with the pattern of parent report data derived from clinical interview noted by Zucker and Bradley (1995).

Examination of demographic correlates of factor score variation were limited to a few variables (age, marital status, social class, IQ). These analyses indicated only modest demographic effects. Nonetheless, in future research, it would be prudent to make an effort to match groups on various demographic variables or at least to consider their influence through covariance analysis.

Regarding the data on sex differences in recalled gender-typed behavior and on the various tests of discriminant validity, one of the most common criticisms of this line of retrospective research pertains to memory distortion or selective recall. Regarding comparative studies of heterosexual and homosexual adults, for example, Ross (1980) advanced a particularly strong version of the retrospective distortion hypothesis: homosexual adults did not really have cross-gender traits or behaviors in childhood but merely remembered themselves that way because they have internalized cultural stereotypes. A variant of this hypothesis regarding recalled differences between heterosexual men and heterosexual women might be as follows: heterosexual men have as many cross-gender traits or behaviors in childhood as heterosexual women but have forgotten about them because they have internalized cultural stereotypes that such behavior is deemed inappropriate.

Regarding Ross’s (1980) claim, it should be noted that there is no direct empirical support for the retrospective distortion hypothesis. Ross’s (1980) study, although often cited as supporting the hypothesis (e.g., Hoult, 1983/1984; Ross, 1984; see also Peplau & Huppin, in press), did not show that homosexual adults’ recollections were affected by beliefs about homosexuality and gender roles; in fact, Ross did not even examine sexual orientation differences in childhood cross-gender behavior. The study merely showed that gay men from Sweden were less likely than gay men from Australia (according to Ross, a more conservative culture than Sweden with respect to gender roles) to believe in such an association (Bailey & Zucker, 1995; Zucker, 2005b).

Despite the consistency of the retrospective studies, skeptics might argue that this is to be expected because of the rather widespread “master narrative” in Western culture that presupposes, for example, that “gender inversion” is linked to homosexuality (Cohler & Galatzer-Levy, 2000; Gottschalk, 2003; Hegarty, 1999). One problem with the master narrative hypothesis, however, is that efforts to attempt a formal experiment to falsify it are rare. To our knowledge, only one study has addressed the question: in a series of experiments, Hegarty (1999) attempted to increase heterosexual university students’ recall of gender conforming behaviors from childhood via certain manipulations. The results did not provide strong support for a reconstructive process.

In our view, there are several lines of research that provide supportive evidence for the veridicality of the gender-typed recollections of adults reported in the present study. First, regarding the data on more recalled cross-gender-typed behavior by women than by men, this finding is entirely consistent with research on “normative” sex differences in children, in which it is very common to find that girls show more variability in their actual gender-typed behavior than do boys (Liben & Bigler, 2002). In a recent study, Khuri (2005) found that elementary and high school girls’ recall of their gender-typed behavior at ages 3–6 years was significantly correlated with recollections made by their mothers; moreover, the girls’ recollection of their degree of early female-typical and male-typical interests showed strong relations to several aspects of their current interests and future plans. For example, level of early female-typical interests predicted current romantic interests (e.g., romance movies) and “mainstream” aspirations (e.g., marriage), whereas level of early male-typical interests predicted current male-typical interests (e.g., sports) and “independent” aspirations (e.g., travel, financial independence).

Second, regarding the data on more recalled cross-gender-typed behavior by homosexual adults than by heterosexual adults, there are two lines of convergent evidence: (a) one study of heterosexual and homosexual men and women showed a significant association between the retrospective recall of childhood gender-typed behavior by the participants and their mothers (Bailey, Willerman, & Parks, 1991), and a second study replicated the finding for homosexual men (Bailey, Nothnagel, & Wolfe, 1995); (b) prospective studies of behaviorally feminine and masculine boys show that the former were disproportionately more likely to develop a homosexual sexual orientation (Green, 1987). And, lastly, regarding the data on more recalled cross-gender-typed behavior by women with CAH than by their sisters, this finding is consistent with observational studies of the gender-typed behavior of CAH girls and their sisters (Berenbaum & Hines, 1992; Pasterski et al., 2005).

Although we have argued that the retrospective data in our study show at least some convergence with other lines of data, this is in no way intended to imply that such data are infallible. Indeed, there is a large literature that has identified various constraints in retrospective methodology; nonetheless, this literature has reached a fairly balanced conclusion, namely that claims that the general unreliability of retrospective reports are exaggerated, but that multiple lines of research are required to complement such investigations (Brewin, Andrews, & Gotlib, 1993; Hardt & Rutter, 2004).

In summary, the results of the present study appear to indicate that our measure of recalled childhood gender-typed behavior has reasonable psychometric properties. Relevant items showed the expected pattern of sex differences, the factor structure was clear, and the tests of discriminant validity indicated the potential to identify significant variation in factor scores between groups (either across or within sex). Because the questionnaire is relatively short in length, it is hoped that it will have practical utility in both clinical settings and in larger research projects in which the role of childhood gender-typed behavior has some theoretical purpose.

References

Allin, S. M. (2000). Are heterosexual men with older brothers more feminine, more sexually interested in other men and more left-handed than men with no older brothers? Unpublished B.A. thesis, Department of Psychology, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Bailey, J. M., Dunne, M. P., & Martin, N. G. (2000). Genetic and environmental influences on sexual orientation and its correlates in an Australian twin sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 524–536.

Bailey, J. M., Nothnagel, J., & Wolfe, M. (1995). Retrospectively measured individual differences in childhood sex-typed behavior among gay men: Correspondence between self- and maternal reports. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 24, 613–622.

Bailey, J. M., & Oberschneider, M. (1997). Sexual orientation and professional dance. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26, 433–444.

Bailey, J. M., Willerman, L., & Parks, C. (1991). A test of the maternal stress theory of human male homosexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 20, 277–293.

Bailey, J. M., & Zucker, K. J. (1995). Childhood sex-typed behavior and sexual orientation: A conceptual analysis and quantitative review. Developmental Psychology, 31, 43–55.

Beard, A. J., & Bakeman, R. (2000). Boyhood gender nonconformity: Reported parental behavior and the development of narcissistic issues. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy, 4, 81–97.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 165–172.

Berenbaum, S. A. (1999). Effects of early androgens on sex-typed activities and interests in adolescents with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Hormones and Behavior, 35, 102–110.

Berenbaum, S. A., & Hines, M. (1992). Early androgens are related to childhood sex-typed toy preferences. Psychological Science, 3, 203–206.

Blanchard, R., & Freund, K. (1983). Measuring masculine gender identity in females. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 205–214.

Bogaert, A. F. (2003). Interaction of older brothers and sex-typing in the prediction of sexual orientation in men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 129–134.

Brewin, C. R., Andrews, A., & Gotlib, I. H. (1993). Psychopathology and early experience: A reappraisal of retrospective reports. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 82–98.

Brown, C. A. (1982). Sex typing in occupational preferences of high school boys and girls. In I. Gross, J. Downing, & A. d’Heurle (Eds.), Sex role attitudes and cultural change (pp. 81–88). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Reidel.

Chivers, M. L., & Bailey, J. M. (2000). Sexual orientation of female-to-male transsexuals: A comparison of homosexual and nonhomosexual types. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29, 259–278.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the social sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cohen, K. M. (2002). Relationships among childhood sex-atypical behavior, spatial ability, handedness, and sexual orientation in men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31, 129–143.

Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & van Goozen, S. H. M. (1997). Sex reassignment of adolescent transsexuals: A follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 263–271.

Cohler, B. J., & Galatzer-Levy, R. M. (2000). The course of gay and lesbian lives: Social and psychoanalytic perspectives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Collaer, M. L., & Hines, M. (1995). Human behavioral sex difference: A role for gonadal hormones during early development? Psychological Bulletin, 118, 55–107.

Comrey, A. L. (1978). Common methodological problems in factor analytic studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 648–659.

Deogracias, J. J., Johnson, L. L., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Kessler, S. J., Schober, J. M., & Zucker, K. J. (2005). The Gender Identity Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Dittmann, R. W., Kappes, M. H., Kappes, M. E., Börger, D., Stegner, H., Willig, R. H., et al. (1990). Congenital adrenal hyperplasia I: Gender-related behavior and attitudes in female patients and their sisters. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 15, 401–420.

Docter, R. F., & Fleming, J. S. (1992). Dimensions of transvestism and transsexualism: The validation and factorial structure of the Cross-Gender Questionnaire. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 5(4), 15–37.

Docter, R. F., & Fleming, J. S. (2001). Measures of transgender behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 30, 255–271.

Dunne, M. P., Bailey, J. M., Kirk, K. M., & Martin, N. G. (2000). The subtlety of sex-atypicality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29, 549–565.

Fisk, N. (1973). Gender dysphoria syndrome (The how, what, and why of a disease). In D. Laub & P. Gandy (Eds.), Proceedings of the Second Interdisciplinary Symposium on Gender Dysphoria Syndrome (pp. 7–14). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Freund, K., Langevin, R., Satterberg, J., & Steiner, B. (1977). Extension of the Gender Identity Scale for males. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 6, 507–519.

Garofano, C. (1993). Personality correlates of sexual desire in a female heterosexual university population. Unpublished B.A. thesis, Department of Psychology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Gottschalk, L. (2003). Same-sex sexuality and childhood gender non-conformity: A spurious connection. Journal of Gender Studies, 12, 35–50.

Green, R. (1987). The “sissy boy syndrome“ and the development of homosexuality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Grossmann, T. (2002). Prähomosexuelle kindheiten: Eine empirische Untersuchung über Geschlecthtsrollenkonformität und -nonkonformität bei homosexuellen Mannern. Zeitschrift für Sexualforschung, 15, 98–119.

Hardt, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 260–273.

Hegarty, P. (1999). Recalling childhood, constructing identity: Norms and stereotypes in theories of sexual orientation. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

Hines, M., Ahmed, S. F., & Hughes, I. A. (2003). Psychological outcomes and gender-related development in complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 93–101.

Hockenberry, S. L., & Billingham, R. E. (1987). Sexual orientation and boyhood gender conformity: Development of the Boyhood Gender Conformity Scale (BGCS). Archives of Sexual Behavior, 16, 475–492.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1975). Four-factor index of social status. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Sociology, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Hoult, T. F. (1983/1984). Human sexuality in biological perspective: Theoretical and methodological perspectives. Journal of Homosexuality, 9, 137–155.

Khuri, J. (2005). The consequences of early female gender-typed behavior: Findings in a female sample. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, New York University, New York.

Landolt, M. A., Bartholomew, K., Saffrey, C., Oram, D., & Perlman, D. (2004). Gender non-conformity, childhood rejection, and adult attachment: A study of gay men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33, 117–128.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Liben, L. S., & Bigler, R. S. (2002). The developmental course of gender differentiation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 67(2, Serial No. 269).

Lippa, R. A. (1998). Gender-related individual differences and the structure of vocational interests: The importance of the “people-things” dimension. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 996–1009.

Lippa, R. A. (2001). On deconstructing and reconstructing masculinity–femininity. Journal of Research in Personality, 35, 168–207.

Loehlin, J. C., & McFadden, D. (2002). Otoacoustic emissions, auditory evoked potentials, and traits related to sex and sexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 115–127.

Mitchell, J. N. (1991). Maternal influences on gender identity disorder in boys: Searching for specificity. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, York University, Downsview, Ontario. Canada.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pasterski, V. L., Geffner, M. E., Brain, C., Hindmarsh, P., Brook, C., & Hines, M. (2005). Prenatal hormones and postnatal socialization by parents as determinants of male-typical toy play in girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Child Development, 76, 264–278.

Peplau, L. A., & Huppin, M. (in press). Masculinity, femininity, and the development of sexual orientation in women. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy.

Phillips, G., & Over, R. (1995). Differences between heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women in recalled childhood experiences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 24, 1–20.

Purcell, D. W. (1995). The effects of parent–child relationships on the relation between gender nonconforming behavior in childhood and psychological adjustment in adulthood. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Emory University, Atlanta, GA.

Ross, M. W. (1980). Retrospective distortion in homosexual research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 9, 523–531.

Ross, M. W. (1984). Beyond the biological model: New directions in bisexual and homosexual research. Journal of Homosexuality, 10, 63–70.

Ruble, D. N., & Martin, C. L. (1998). Gender development. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), The handbook of child psychology (5th ed.): Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 933–1016). New York: Wiley.

Safir, M. P., Rosenmann, A., & Kloner, O. (2003). Tomboyism, sexual orientation, and adult gender roles among Israeli women. Sex Roles, 48, 401–410.

Singh, D., Vidaurri, M., Zambarano, R. J., & Dabbs, J. M. (1999). Lesbian erotic role identification: Behavioral, morphological, and hormonal correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 1035–1049.

Spence, J. T., & Helmreich, R. L. (1978). Masculinity and femininity: Their psychological dimensions, correlates, and antecedents. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Stoller, R. J. (1965). The sense of maleness. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 34, 207–218.

Stoller, R. J. (1968a). The sense of femaleness. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 37, 42–55.

Stoller, R. J. (1968b). Male childhood transsexualism. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 7, 193–209.

Strong, S. M., Singh, D., & Randall, P. K. (2000). Childhood gender nonconformity and body dissatisfaction in gay and heterosexual men. Sex Roles, 43, 427–439.

Taywaditep, K. J. (2001). Marginalization among the marginalized: Gay men’s negative attitudes toward effeminacy. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Tkachuk, J., & Zucker, K. J. ( 1991, August).The relation among sexual orientation, spatial ability, handedness, and recalled childhood gender identity in women and men. Poster presented at the meeting of the International Academy of Sex Research, Barrie, Ontario, Canada.

Tortorice, J. L. (2002). Written on the body: Butch/femme lesbian gender identity and biological correlates. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

Vonk, R., & Ashmore, R. D. (2003). Thinking about gender types: Cognitive organization of female and male types. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 257–280.

Whitam, F. L., Daskalos, C., Sobolewski, C. G., & Padilla, P. (1998). The emergence of lesbian sexuality and identity cross-culturally: Brazil, Peru, the Philippines, and the United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 27, 31–56.

Willemsen, T. M., & Fischer, A. H. (1999). Assessing multiple facets of gender identity: The Gender Identity Questionnaire. Psychological Reports, 84, 561–562.

Zucker, K. J. (1992). Gender identity disorder. In S. R. Hooper, G. W. Hynd, & R. E. Mattison (Eds.), Child psychopathology: Diagnostic criteria and clinical assessment (pp. 305–342). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Zucker, K. J. (2005a). Measurement of psychosexual differentiation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34, 375–388.

Zucker, K. J. (2005b). Commentary on Gottschalk’s (2003) “Same-sex Sexuality and Childhood Gender Non-conformity: a spurious connection.” Journal of Gender Studies, 14, 55–60.

Zucker, K. J., & Bradley, S. J. (1995). Gender identity disorder and psychosexual problems in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford.

Zucker, K. J., Bradley, S. J., Sullivan, C. B. L., Kuksis, M., Birkenfeld-Adams, A., & Mitchell, J. N. (1993). A gender identity interview for children. Journal of Personality Assessment, 61, 443–456.

Zucker, K. J., Bradley, S. J., Oliver, G., Blake, J., Fleming, S., & Hood, J. (1996). Psychosexual development of women with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Hormones and Behavior, 30, 300–318.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the meeting of the International Academy of Sex Research, Barrie, Ontario (August 1991) and Hamburg, Germany (June 2002). Dr. Mitchell died on March 16, 2000, and we dedicate this article to her memory.

Appendix: The Recalled Childhood Gender Identity/Gender Role Questionnaire (form for males)

Appendix: The Recalled Childhood Gender Identity/Gender Role Questionnaire (form for males)

Instructions

Please answer the following questions about your behavior as a child, that is, the years “0 to 12.” For each question, circle the response that best describes your behavior as a child. Please note that there are no “right or wrong” answers.

-

1.

As a child, my favorite playmates were

-

a.

always boys (5)

-

b.

usually boys (4)

-

c.

boys and girls equally (3)

-

d.

usually girls (2)

-

e.

always girls (1)

-

f.

I did not play with other children

-

a.

-

2.

As a child, my best or closest friend was

-

a.

always a boy (5)

-

b.

usually a boy (4)

-

c.

a boy or a girl (3)

-

d.

usually a girl (2)

-

e.

always a girl (1)

-

f.

I did not have a best or close friend

-

a.

-

3.

As a child, my favorite toys and games were

-

a.

always “masculine” (5)

-

b.

usually “masculine” (4)

-

c.

equally “masculine” and “feminine” (3)

-

d.

usually “feminine” (2)

-

e.

always “feminine” (1)

-

f.

neither “masculine” or “feminine”

-

a.

-

4.

Compared to other boys, my activity level was

-

a.

very high (5)

-

b.

higher than average (4)

-

c.

average (3)

-

d.

lower than average (2)

-

e.

very low (1)

-

a.

-

5.

As a child, I experimented with cosmetics (make-up) and jewelry

-

a.

as a favorite activity (1)

-

b.

frequently (2)

-

c.

once-in-a-while (3)

-

d.

very rarely (4)

-

e.

never (5)

-

a.

-

6.

As a child, the characters on TV or in the movies that I imitated or admired were

-

a.

always girls or women (1)

-

b.

usually girls or women (2)

-

c.

girls/women and boys/men equally (3)

-

d.

usually boys or men (4)

-

e.

always boys or men (5)

-

f.

I did not imitate or admire characters on TV or in the movies

-

a.

-

7.

As a child, I enjoyed playing sports such as baseball, hockey, basketball, and soccer

-

a.

only with boys (5)

-

b.

usually with boys (4)

-

c.

with boys and girls equally (3)

-

d.

usually with girls (2)

-

e.

only with girls (1)

-

f.

I did not play these types of sports

-

a.

-

8.

In fantasy or pretend play, I took the role

-

a.

only of boys or men (5)

-

b.

usually of boys or men (4)

-

c.

boys/men and girls/women equally (3)

-

d.

usually of girls or women (2)

-

e.

only of girls or women (1)

-

f.

I did not do this type of pretend play

-

a.

-

9.

In dress-up play, I would

-

a.

wear boys’ or men’s clothing all the time (5)

-

b.

usually wear boys’ or men’s clothing (4)

-

c.

half the time wear boys’ or men’s clothing and half the time wear girls’ or women’s clothing (3)

-

d.

usually wear girls’ or women’s clothing (2)

-

e.

wear girls’ or women’s clothing all the time (1)

-

f.

I did not do this type of play

-

a.

-

10.

As a child, I felt

-

a.

very masculine (5)

-

b.

somewhat masculine (4)

-

c.

masculine and feminine equally (3)

-

d.

somewhat feminine (2)

-

e.

very feminine (1)

-

f.

I did not feel masculine or feminine

-

a.

-

11.

As a child, compared to other boys my age, I felt

-

a.

much more masculine (5)

-

b.

somewhat more masculine (4)

-

c.

equally masculine (3)

-

d.

somewhat less masculine (2)

-

e.

much less masculine (1)

-

a.

-

12.

As a child, compared to my brother, I felt

-

a.

much more masculine (5)

-

b.

somewhat more masculine (4)

-

c.

equally masculine (3)

-

d.

somewhat less masculine (2)

-

e.

much less masculine (1)

-

f.

I did not have a brother [Note: If you had more than one brother, make your comparison with the brother closest in age to you.]

-

a.

-

13.

As a child, I

-

a.

always resented or disliked my sister (1)

-

b.

usually resented or disliked my sister (2)

-

c.

sometimes resented or disliked my sister (3)

-

d.

rarely resented or disliked my sister (4)

-

e.

never resented or disliked my sister (5)

-

f.

I did not have a sister [Note: If you had more than one sister, make your comparison with the sister closest in age to you.]

-

a.

-

14.

As a child, my appearance (hair style, clothing, etc.) was

-

a.

very masculine (5)

-

b.

somewhat masculine (4)

-

c.

equally masculine and feminine (3)

-

d.

somewhat feminine (2)

-

e.

very feminine (1)

-

f.

neither masculine or feminine

-

a.

-

15.

As a child, I

-

a.

always enjoyed wearing dresses and other “feminine” clothes (1)

-

b.

usually enjoyed wearing dresses and other “feminine” clothes (2)

-

c.

sometimes enjoyed wearing dresses and other “feminine” clothes (3)

-

d.

rarely enjoyed wearing dresses and other “feminine” clothes (4)

-

e.

never enjoyed wearing dresses and other “feminine” clothes (5)

-

a.

-

16.

As a child, I was

-

a.

emotionally closer to my mother than to my father (1)

-

b.

somewhat emotionally closer to my mother than to my father (2)

-

c.

equally close emotionally to my mother and to my father (3)

-

d.

somewhat emotionally closer to my father than to my mother (4)

-

e.

emotionally closer to my father than to my mother (5)

-

f.

not emotionally close to either my mother or to my father

-

a.

-

17.

As a child, I

-

a.

admired my mother and my father equally (3)

-

b.

admired my father more than my mother (4)

-

c.

admired my mother more than my father (1)

-

d.

admired neither my mother nor my father (2)

-

a.

-

18.

As a child, I had the reputation of a “sissy”

-

a.

all of the time (1)

-

b.

most of the time (2)

-

c.

some of the time (3)

-

d.

on rare occasions (4)

-

e.

never (5)

-

a.

-

19.

As a child, I

-

a.

always felt good about being a boy (5)

-

b.

usually felt good about being a boy (4)

-

c.

sometimes felt good about being a boy (3)

-

d.

rarely felt good about being a boy (2)

-

e.

never felt good about being a boy (1)

-

f.

never really thought about how I felt being a boy

-

a.

-

20.

As a child, I had the desire to be a girl but did not tell anyone

-

a.

almost always (1)

-

b.

frequently (2)

-

c.

sometimes (3)

-

d.

rarely (4)

-

e.

never (5)

-

a.

-

21.

As a child, I would tell others I wanted to be a girl

-

a.

almost always (1)

-

b.

frequently (2)

-

c.

sometimes (3)

-

d.

rarely (4)

-

e.

never (5)

-

a.

-

22.

As a child, I

-

a.

always felt that my mother cared about me (1)

-

b.

usually felt that my mother cared about me (2)

-

c.

sometimes felt that my mother cared about me (3)

-

d.

rarely felt that my mother cared about me (4)

-

e.

never felt that my mother cared about me (5)

-

f.

cannot answer because I did not live with my mother (or know her)

-

a.

-

23.

As a child, I

-

a.

always felt that my father cared about me (1)

-

b.

usually felt that my father cared about me (2)

-

c.

sometimes felt that my father cared about me (3)

-

d.

rarely felt that my father cared about me (4)

-

e.

never felt that my father cared about me (5)

-

f.

cannot answer because I did not live with my father (or know him)

-

a.

Form for females

-

1.

As a child, my favorite playmates were

-

a.

always boys (1)

-

b.

usually boys (2)

-

c.

boys and girls equally (3)

-

d.

usually girls (4)

-

e.

always girls (5)

-

f.

I did not play with other children

-

a.

-

2.

As a child, my best or closest friend was

-

a.

always a boy (1)

-

b.

usually a boy (2)

-

c.

a boy or a girl (3)

-

d.

usually a girl (4)

-

e.

always a girl (5)

-

f.

I did not have a best or close friend

-

a.

-

3.

As a child, my favorite toys and games were

-

a.

always “masculine” (1)

-

b.

usually “masculine” (2)

-

c.

equally “masculine” and “feminine” (3)

-

d.

usually “feminine” (4)

-

e.

always “feminine” (5)

-

f.

neither “masculine” or “feminine”

-

a.

-

4.

Compared to other girls, my activity level was

-

a.

very high (1)

-

b.

higher than average (2)

-

c.

average (3)

-

d.

lower than average (4)

-

e.

very low (5)

-

a.

-

5.

As a child, I experimented with cosmetics (make-up) and jewelry

-

a.

as a favorite activity (5)

-

b.

frequently (4)

-

c.

once-in-a-while (3)

-

d.

rarely (2)

-

e.

never (1)

-

a.

-

6.

As a child, the characters on TV or in the movies that I imitated or admired were

-

a.

always girls or women (5)

-

b.

usually girls or women (4)

-

c.

girls/women and boys/men equally (3)

-

d.

usually boys or men (2)

-

e.

always boys or men (1)

-

f.

I did not imitate or admire characters on TV or in the movies

-

a.

-

7.

As a child, I enjoyed playing sports such as baseball, hockey, basketball, and soccer

-

a.

only with boys (1)

-

b.

usually with boys (2)

-

c.

with boys and girls equally (3)

-

d.

usually with girls (4)

-

e.

only with girls (5)

-

f.

I did not play these types of sports

-

a.

-

8.

In fantasy or pretend play, I took the role

-

a.

only of boys or men (1)

-

b.

usually of boys or men (2)

-

c.

boys/men and girls/women equally (3)

-

d.

usually of girls or women (4)

-

e.

only of girls or women (5)

-

f.

I did not do this type of pretend play

-

a.

-

9.

In dress-up play, I would

-

a.

wear boys’ or men’s clothing all the time (1)

-

b.

usually wear boys’ or men’s clothing (2)

-

c.

half the time wear boys’ or men’s clothing and half the time wear girls’ or women’s clothing (3)

-

d.

usually wear girls’ or women’s clothing (4)

-

e.

wear girls’ or women’s clothing all the time (5)

-

f.

not do this type of play

-

a.

-

10.

As a child, I felt

-

a.

very masculine (1)

-

b.

somewhat masculine (2)

-

c.

masculine and feminine equally (3)

-

d.

somewhat feminine (4)

-

e.

very feminine (5)

-

f.

I did not feel masculine or feminine

-

a.

-

11.

As a child, compared to other girls my age, I felt

-

a.

much more feminine (5)

-

b.

somewhat more feminine (4)

-

c.

equally feminine (3)

-

d.

somewhat less feminine (2)

-

e.

much less feminine (1)

-

a.

-

12.

As a child, compared to my sister (closest to you in age), I felt

-

a.

much more feminine (5)

-

b.

somewhat more feminine (4)

-

c.

equally feminine (3)

-

d.

somewhat less feminine (2)

-

e.

much less feminine (1)

-

f.

I did not have a sister [Note: If you had more than one sister, make your comparison with the sister closest in age to you.]

-

a.

-

13.

As a child, I

-

a.

always resented or disliked my brother (1)

-

b.

usually resented or disliked my brother (2)

-

c.

sometimes resented or disliked my brother (3)

-

d.

rarely resented or disliked my brother (4)

-

e.

never resented or disliked my brother (5)

-

f.

I did not have a brother [Note: If you had more than one brother, make your comparison with the brother closest in age to you.]

-

a.

-

14.

As a child, my appearance (hair-style, clothing, etc.) was

-

a.

very feminine (5)

-

b.

somewhat feminine (4)

-

c.

equally masculine and feminine (3)

-

d.

somewhat masculine (2)

-

e.

very masculine (1)

-

f.

neither masculine or feminine

-

a.

-

15.

As a child, I

-

a.

always enjoyed wearing dresses and other “feminine” clothes (5)

-

b.

usually enjoyed wearing dresses and other “feminine” clothes (4)

-

c.

sometimes enjoyed wearing dresses and other “feminine” clothes (3)

-

d.

rarely enjoyed wearing dresses and other “feminine” clothes (2)

-

e.

never enjoyed wearing dresses and other “feminine” clothes (1)

-

a.

-

16.

As a child, I was

-

a.

emotionally closer to my mother than to my father (5)

-

b.

somewhat emotionally closer to my mother than to my father (4)

-

c.

equally close emotionally to my mother and to my father (3)

-

d.

somewhat emotionally closer to my father than to my mother (2)

-

e.

emotionally closer to my father than to my mother (1)

-

f.

not emotionally close to either my mother or to my father

-

a.

-

17.

As a child, I

-

a.

admired my mother and my father equally (3)

-

b.

admired my father more than my mother (1)

-

c.

admired my mother more than my father (4)

-

d.

admired neither my mother nor my father (2)

-

a.

-

18.

As a child, I had the reputation of a “tomboy”

-

a.

all of the time (1)

-

b.

most of the time (2)

-

c.

some of the time (3)

-

d.

on rare occasions (4)

-

e.

never (5)

-

a.

-

19.

As a child, I

-

a.

always felt good about being a girl (5)

-

b.

usually felt good about being a girl (4)

-

c.

sometimes felt good about being a girl (3)

-

d.

rarely felt good about being a girl (2)

-

e.

never felt good about being a girl (1)

-

f.

never really thought about how I felt being a girl

-

a.

-

20.

As a child, I had the desire to be a boy but did not tell anyone

-

a.

almost always (1)

-

b.

frequently (2)

-

c.

sometimes (3)

-

d.

rarely (4)

-

e.

never (5)

-

a.

-

21.

As a child, I would tell others that I wanted to be a boy

-

a.

almost always (1)

-

b.

frequently (2)

-

c.

sometimes (3)

-

d.

rarely (4)

-

e.

never (5)

-

a.

-

22.

As a child, I

-

a.

always felt that my mother cared about me (5)

-

b.

usually felt that my mother cared about me (4)

-

c.

sometimes felt that my mother cared about me (3)

-

d.

rarely felt that my mother cared about me (2)

-

e.

never felt that my mother cared about me (1)

-

f.

cannot answer because I did not live with my mother (or know her)

-

a.

-

23.

As a child, I

-

a.

always felt that my father cared about me (1)

-

b.

usually felt that my father cared about me (2)

-

c.

sometimes felt that my father cared about me (3)

-

d.

rarely felt that my father cared about me (4)

-

e.

never felt that my father cared about me (5)

-

f.

cannot answer because I did not live with my father (or know him)

-

a.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zucker, K.J., Mitchell, J.N., Bradley, S.J. et al. The Recalled Childhood Gender Identity/Gender Role Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties. Sex Roles 54, 469–483 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9019-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9019-x