Abstract

Purpose

Many conservative interventions are used in the management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). It could be helpful for the prescribers to know what the evidence suggests about the effects of these interventions on the long-term quality of life (QoL), depression, and anxiety. This study aimed to summarize the rationale for the use of conservative interventions to improve the long-term QoL, depression, and anxiety in patients with stable COPD.

Methods

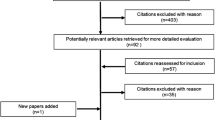

The MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases were searched from database inception to December 2019. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) investigating the long-term effects of conservative interventions on three parameters, including QoL, depression, and anxiety in patients with COPD were eligible for further analysis. To improve methodological rigor, only RCTs examining these parameters as primary outcomes were included. The standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using random effects models. Quality of evidence was rated using the updated version of Van Tulder’s criteria.

Results

Thirty-eight RCTs were identified. Regarding long-term depression, there was moderate evidence supporting cognitive behavioral therapy compared with usual care in patients with COPD; regarding the long-term QoL of patients with COPD, there was limited evidence supporting walking programs, supplementary sugarcane bagasse dietary fiber, roflumilast, and tiotropium.

Conclusions

Cognitive behavioral therapy is effective in alleviating the long-term depression of patients with COPD. Evidence for other interventions was insufficient, making it difficult to draw conclusions in terms of their effectiveness on the long-term QoL, depression, and anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation [1]. COPD is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide that induces a substantial economic and social burden [1]. Extrapulmonary comorbidities in COPD are common and can be very detrimental, including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and diabetes [1]. Interestingly, extrapulmonary brain-related comorbidities of COPD, such as depression and anxiety, are also common. The prevalence of depression and anxiety is higher among patients with COPD than the prevalence among non-COPD individuals [2]. Despite the increased prevalence, mental issues among COPD individuals are somewhat neglected by the medical community compared to the physical problems.

Associations between adverse psychological factors and COPD are well established. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis revealed a bidirectional relationship between depression or anxiety and COPD, that depression and anxiety adversely affected prognosis of COPD, and conversely, COPD increased the risk of developing depression [3]. The overall health status of an individual with COPD is the result of interplay between psychological and physical factors, as COPD is nowadays considered as a multicomponent disease, despite being defined by the presence of persistent airflow limitation [4]. Mental health complications are associated with worsening of disease progression, as evidenced by increased mortality and frequency of exacerbations, and decreased exercise capacity in depressed and anxious COPD patients [5,6,7,8].

Quality of life (QoL) is decreased in COPD patients due to physical and psychological impairments [9], of which depression and anxiety have a stronger association with the reduced QoL in COPD, compared with the widely used spirometric value [10]. Since QoL is considered a major goal in managing the disease, therapies should be focused on improving it.

QoL, depression, and anxiety are important indicators of psychological well-being in patients with COPD. A summary of evidence regarding the efficacy of different interventions on psychological well-being may support clinical treatment decision-making. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review (SR) and meta-analysis to synthesize evidence of different conservative interventions in improving long-term QoL, depression, and anxiety in patients with stable COPD.

Materials and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11]. The study was registered in PROSPERO (Registration Number: CRD42020216443).

Search strategy

We searched the MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase (via Ovid), Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases for relevant articles from database inception to December 2019. Reference list of the included studies were also reviewed for potential eligible trials. The search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Selection criteria

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility. Full-text reviews were then performed. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third reviewer when needed. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that investigate the effectiveness of any conservative interventions on QoL, depression, and anxiety in patients with stable COPD were included. Specifically, studies were included if they met the following criteria:

-

1.

Participants: Participants were patients with stable COPD of any disease severity. We excluded studies whose participants had acute exacerbations of COPD at enrollment. There was no restriction on age, sex, race, or comorbidities of the participants.

-

2.

Interventions: No restrictions were placed on the intervention, except that the intervention should be “conservative.” Surgery or other invasive procedures, such as lung volume reduction surgery or lung transplantation, were considered non-conservative.

-

3.

Outcomes: Studies were eligible whose primary outcomes were QoL and/or depression and/or anxiety. Studies that only provided scores of the QoL subscale instead of the total score were excluded. Focusing on primary outcomes is a useful strategy for improving methodological rigor [12]. The primary outcome of RCT is the basis for the estimation of sample size, which therefore increases the power of the study to find differences in this specific outcome, and the intervention is more likely to be targeted to the primary outcome [12]. Therefore, only studies that considered QoL, depression, and anxiety as their primary outcomes were included in this SR. We considered the outcome as primary if it was directly described by the study as “primary,” “main,” or “key” outcomes. When no outcome was specified as the primary outcome, the outcome that was used in the power analysis was considered the primary outcome. If an RCT did not specify the primary outcome or did not use a certain outcome to perform power analysis, the RCT was excluded. Since we only focused on the long-term benefits of interventions, we only included studies with a follow-up ≥ 6 months (or 24 weeks).

-

4.

Study design: The study design was limited to RCTs.

The language was limited to English. In case the relevant data could not be obtained through the published manuscript, the corresponding author was contacted to request the data. If we could not obtain the data after the contact, the study was excluded.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted the data from the included studies. A third reviewer was involved in case of discrepancies.

Assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias

Methodological quality assessment of each study was performed using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale [13]. Scores on the PEDro scale range from 0 (very low methodological quality) to 10 (high methodological quality). Besides, the risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool [14]. All assessments were performed by two independent reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer when needed.

Data management and statistical analysis

Pooling of data was conducted where studies investigated similar interventions using comparable outcome measures. When data could not be pooled due to the limited number the studies (i.e., fewer than two studies), they were summarized in a forest plot (without an overall pooled estimate of effect) to give easy visualization of the results. We calculated the standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% CIs using random effects models for continuous data. Heterogeneity was quantified by the I2 statistic. Data analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4 [15]. For each finding, we rated the level of evidence as “strong,” “moderate,” “limited,” “very limited,” and “conflicting,” using the updated version of Van Tulder’s criteria [16]. According to the criteria, the level of evidence was determined based on the number and the quality of studies, and the degree of statistical homogeneity among the studies. Detailed information of this criteria is available in Supplementary Table S2.

Results

Study characteristics

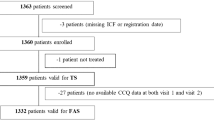

The flowchart of the study selection is provided in Fig. 1. Thirty-eight studies were eligible for inclusion in the current SR. Most of the included studies (N = 34) evaluated QoL, four studies evaluated depression, and four studies evaluated anxiety in patients with COPD as the primary outcome.

Methodological quality assessment and assessment of bias risk

The PEDro quality assessment for each study is listed in Supplementary Table S3. Fourteen studies were rated as high quality [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], and 24 studies as low quality [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Lack of blinding to the subjects and therapist was the most common methodological limitation of the studies, which could be explained by the difficulty in blinding due to the design of the interventions.

The assessment of the bias risk of each included study is presented in Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2. Similarly, the most common risk of bias was the lack of blinding to the patients, personnel, and assessors.

Meta-analyses

A summary of the findings of the meta-analyses is presented in Table 1.

Effects of interventions on QoL

The results that could be pooled are presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4; the results that could not be pooled are presented in Fig. 5.

Effects of other interventions on long-term QoL, depression, and anxiety. Comparisons presented in figure are (1) Indacaterol/glycopyrronium 110 μg/50 μg once daily VS Tiotropium 18 μg once daily plus formoterol 12 μg twice daily; (2) Home-based nocturnal non-invasive ventilation plus PR VS PR alone; (3) Rehabilitation in cold VS in warm climate; (4) fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol 100 µg/62.5 µg/25 µg once daily VS budesonide/formoterol 400 µg/12 µg twice daily; (5) Sugarcane bagasse dietary fiber VS placebo; (6) Honey supplementation VS usual care; (7) Roflumilast 250 mg or 500 mg once daily VS placebo; (8) Ginseng capsules 100 mg twice daily VS placebo; (9) Supervised, outpatient-based exercise plus unsupervised home exercise following PR VS standard care of unsupervised home exercise training; (10) Tiotropium 18 mg once daily VS placebo; (11) Bushen Fangchuan tablets VS placebo; (12) Bushen Yiqi granule VS placebo; (13) and (14) Guided self-change sessions plus nicotine replacement therapy VS nicotine replacement therapy alone

Effects of an integrated pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) program on long-term QoL

Overall, three studies [28, 39, 46] (414 participants) provided with limited level of evidence that an integrated PR program was not superior to control interventions in improving long-term QoL in patients with COPD (SMD = − 0.37, CI − 1.14 to 0.40, p = 0.34, I2 = 93%). Specifically, pooled data from two studies (304 participants) showed that an integrated PR program was not effective compared to usual care to improve long-term QoL (SMD = − 0.69, CI − 1.56 to 0.19, p = 0.12, I2 = 93%). One study (110 participants) showed that an integrated PR program was as effective as Tai Chi in improving long-term QoL (SMD = 0.27, CI − 0.11 to 0.64, p = 0.16) (Fig. 2A).

Effects of exercise on long-term QoL

Three studies investigated the effects of exercise [32, 43, 51] (302 participants). Pooled data demonstrated that exercise was not superior to control in improving the long-term QoL of patients with COPD. The level of evidence was considered limited according to the Van Tulder’s criteria. Specifically, in the comparison of exercise VS usual care, or exercise + PR VS PR alone, the difference was not statistically significant (SMD = − 0.50, CI − 1.21 to 0.21, p = 0.17) (SMD = 0.36, CI − 0.44 to 0.76, p = 0.08) (Fig. 2B).

Effects of self-management and education on long-term QoL

Eleven studies [25, 33, 34, 42, 44, 45, 48,49,50, 52, 54] (1737 participants) evaluated the effectiveness of self-management and education in the long-term QoL of patients compared with control interventions. The evidence derived from these studies was conflicting according to the Van Tulder’s criteria. Specifically, there was moderate evidence from three studies (714 participants) that self-management and education (meeting or coaching) was not superior to educational booklets in improving long-term QoL in COPD patients (SMD = − 0.15, CI − 0.30 to 0.00, p = 0.05, I2 = 0%). There was conflicting evidence from eight studies (1023 participants) as to the effectiveness of self-management and education compared with usual care in long-term QoL (SMD = − 0.17, CI − 0.85 to 0.50, p = 0.62, I2 = 96%) (Fig. 3A).

Effects of physical activity on long-term QoL

Limited evidence from one study [21] (125 participants) suggested that the walking program was superior to usual care in improving long-term QoL (SMD = − 0.40, CI − 0.77 to − 0.04, p = 0.03) (Fig. 3B). There was limited evidence from two studies [22, 37] (309 participants) that the walking program with active feedback demonstrated no superiority over walking without active feedback (SMD = − 0.19, CI − 0.47 to 0.10, p = 0.21, I2 = 25%) (Fig. 3B).

Effects of telemonitoring on long-term QoL

Pool data from two studies [29, 53] (591 participants) suggested that telemonitoring was not effective compared to usual care in long-term QoL (SMD = 0.15, CI − 0.12 to 0.42, p = 0.28, I2 = 64%) (Fig. 3C). Level of evidence was limited.

Effects of other interventions on long-term QoL

Limited evidence suggested that supplementary sugarcane bagasse dietary fiber [20] (SMD = − 0.56, CI − 0.87 to − 0.25, p = 0.0004), roflumilast [17] (SMD = − 2.51, CI − 2.70 to − 2.31, p < 0.00001), and tiotropium [27] (SMD = − 0.30, CI − 0.47 to − 0.12, p = 0.001) were superior to control interventions (e.g., conventional treatment or placebo) in improving long-term QoL in patients with COPD (Fig. 5).

Limited evidence suggested that two-year home-based nocturnal non-invasive ventilation added to PR was not superior to PR alone [23], and that 24 weeks of once-daily triple therapy (fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol 100 µg/62.5 µg/25 µg; ELLIPTA ® inhaler) were as effective as 24 weeks of twice-daily ICS/LABA therapy (budesonide/formoterol 400 µg/12 µg; Turbuhaler ®) [19]. Additionally, limited evidence showed that Bushen Fangchuan tablet [26], Bushen Yiqi granule [26], and ginseng extract [18] were not effective compared to placebo in improving long-term QoL (Fig. 5).

There was very limited evidence that a 6-month regime of honey supplementation was superior to standard care in improving the long-term QoL of patients with COPD [38] (SMD = − 1.05, CI − 1.80 to − 0.30, p = 0.006). There was also very limited evidence that supervised, outpatient-based exercise plus unsupervised home exercise following PR was superior to unsupervised home exercise training alone in improving long-term QoL [41] (SMD = 0.64, CI 0.06 to 1.22, p = 0.03) (Fig. 5).

There was also very limited evidence that once-daily indacaterol plus glycopyrronium was as effective as once-daily tiotropium plus twice-daily formoterol [31], and that rehabilitation in a warm climate compared with that in a colder climate [35] were as effective in improving long-term QoL in individuals with COPD (Fig. 5).

Effect of interventions on long-term depression and anxiety

Only the data from studies investigating cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) could be pooled (Fig. 4). Data that could not be pooled are presented in Fig. 5.

Effects of CBT on long-term depression

There was moderate evidence from three studies (209 participants) that CBT was superior to usual care in improving long-term depression in patients with COPD [36, 40, 47] (SMD = − 0.50, CI − 0.78 to − 0.22, p = 0.0005, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 4A).

Effect of other interventions on long-term depression

There was limited evidence from one study that a guided self-change combined with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) did not add more benefits compared with NRT alone in improving long-term depression in patients with COPD [30] (Fig. 5).

Effects of CBT on anxiety

There was limited evidence from three studies [24, 40, 47] (264 participants) that CBT was not effective compared to usual care in improving long-term anxiety in patients with COPD (Fig. 4B).

Effects of other interventions on long-term anxiety

There was limited evidence that a guided self-change combined with NRT was not superior to NRT alone in improving long-term anxiety in patients with COPD [30] (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This SR identified 38 studies that investigated the effects of interventions on QoL and/or depression and/or anxiety as primary outcomes in patients with COPD. The main findings were as follows: regarding long-term depression, there was moderate evidence supporting the use of CBT compared with usual care in patients with COPD; regarding the long-term QoL of patients with COPD, there was limited evidence supporting the use of walking programs, supplementary sugarcane bagasse dietary fiber, roflumilast, and tiotropium compared with control interventions.

In a meta-analysis by Ma et al. [55], CBT was reported to be effective in improving depression and anxiety in individuals with COPD. However, that study did not specify how long the benefits could be maintained. Our SR extended these findings with a moderate level of evidence that CBT was more effective than usual care in improving long-term depression in patients with COPD. While in regard to the benefits for long-term anxiety, current evidence is insufficient to support the superiority of CBT to usual care.

The latest report of the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (GOLD) has recommended active lifestyle and exercise, self-management, and pulmonary rehabilitation in the management of stable COPD [1]. To our surprise, the results of this SR did not support exercise, self-management and education or PR in improving long-term QoL in stable COPD. One possible reason is that the benefits of these interventions diminish over time in COPD if activity and other positively adaptive behaviors are not continued after the completion of the interventions [56]. This finding highlights the importance of a maintenance program following the intervention that encourages sufficient activity and positively adaptive behaviors in daily life. However, the level of evidence was generally weak (most were rated as “limited” or “very limited”) due to the low number of studies for the same intervention or the tremendous heterogeneity in the pooled data. Therefore, caution must be taken when interpreting the results.

Pharmacological therapies are another important component in the management of stable COPD. They can reduce symptoms and the risk and severity of exacerbations, as well as improve exercise tolerance and the health status and of patients with COPD [1]. This SR demonstrated that roflumilast, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, and tiotropium, a long-acting anticholinergic bronchodilator, are more effective in improving the long-term QoL than placebo. However, many studies that investigated the effects of pharmacological therapies on COPD were not included in the current study. One important reason was that these studies did not employ QoL, depression, or anxiety but spirometry parameters, exacerbation rate, or hospitalizations as their primary outcomes; therefore, they did not meet our inclusion criteria.

Our study focused on three important outcomes of COPD patients, i.e., quality of life, depression, and anxiety. However, except for quality of life, studies measuring the depression and anxiety as their primary outcomes were scarce. Although many studies took them as secondary outcomes, considering the pivotal role of a primary outcome in an RCT, the scarcity of studies primarily examining depression and anxiety has partly proved the notion that mental health of COPD patients was overlooked by the medical community. Besides the physical problems, the improvement of patients’ mental health is as well an important goal in the treatment of COPD, therefore, future studies focusing on the efficacy of interventions on long-term depression and anxiety are in need.

Limitations

There were several limitations in this study. First, the limited number of studies for each intervention reduced the power of the meta-analysis. Second, we set strict eligibility criteria in an attempt to raise the methodological quality of our study. For example, only the studies that employed QoL, depression, and anxiety as the primary outcomes were included. This could lead to missing some studies that considered QoL, depression, and anxiety as secondary outcomes, and some interventions could be omitted. Third, although we only compared studies with similar interventions, we still cannot neglect the heterogeneity of interventions and their corresponding control conditions among different studies. For example, in some RCTs included in the present study, subjects in the control group were assigned to usual care, a term most commonly refers to routine care provided for the target problem in the trial setting. However, usual care can range depending on different settings, from guideline-driven, gold-standard care, to highly variable care to no care [57]. The variability of usual care among trials is a potential source of clinical heterogeneity and merits attention when interpreting the results. Last, due to language restriction, we only included articles written in English. These limitations could reduce the power of this study.

Conclusions

CBT is effective in improving long-term depression in patients with COPD. There was limited evidence that the walking program, supplementary sugarcane bagasse dietary fiber, roflumilast, and tiotropium may be effective in improving long-term QoL in patients with COPD. Evidence for other interventions was insufficient, making it difficult to draw conclusions in terms of their effectiveness on the long-term QoL, depression, and anxiety.

Data availability

Data available within the article or its supplementary materials.

References

Singh, D., Agusti, A., Anzueto, A., Barnes, P. J., Bourbeau, J., Celli, B. R., Criner, G. J., Frith, P., Halpin, D., Han, M., López Varela, M. V., Martinez, F., Montes de Oca, M., Papi, A., Pavord, I. D., Roche, N., Sin, D. D., Stockley, R., Vestbo, J., Wedzicha, J. A., & Vogelmeier, C. (2019). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease: The GOLD science committee report 2019. The European respiratory journal, 53(5), 1900164. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00164-2019.

Di Marco, F., Verga, M., Reggente, M., Maria Casanova, F., Santus, P., Blasi, F., Allegra, L., & Centanni, S. (2006). Anxiety and depression in COPD patients: The roles of gender and disease severity. Respiratory Medicine, 100(10), 1767–1774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2006.01.026

Atlantis, E., Fahey, P., Cochrane, B., & Smith, S. (2013). Bidirectional associations between clinically relevant depression or anxiety and COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest, 144(3), 766–777. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-1911

Franssen, F. M. E., Smid, D. E., Deeg, D. J. H., Huisman, M., Poppelaars, J., Wouters, E. F. M., & Spruit, M. A. (2018). The physical, mental, and social impact of COPD in a population-based sample: Results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine, 28(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-018-0097-3

Pumar, M. I., Gray, C. R., Walsh, J. R., Yang, I. A., Rolls, T. A., & Ward, D. L. (2014). Anxiety and depression—Important psychological comorbidities of COPD. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 6(11), 1615–1631. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.09.28

Maurer, J., Rebbapragada, V., Borson, S., Goldstein, R., Kunik, M. E., Yohannes, A. M., & Hanania, N. A. (2008). Anxiety and depression in COPD: Current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needs. Chest, 134(4 Suppl), 43s–56s. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-0342

Huang, J., Bian, Y., Zhao, Y., Jin, Z., Liu, L., & Li, G. (2021). The impact of depression and anxiety on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease acute exacerbations: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.030

Yohannes, A. M., & Alexopoulos, G. S. (2014). Depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. European Respiratory Review, 23(133), 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1183/09059180.00007813

Janson, C., Marks, G., Buist, S., Gnatiuc, L., Gislason, T., McBurnie, M. A., Nielsen, R., Studnicka, M., Toelle, B., Benediktsdottir, B., & Burney, P. (2013). The impact of COPD on health status: Findings from the BOLD study. European Respiratory Journal, 42(6), 1472–1483. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00153712

Tsiligianni, I., Kocks, J., Tzanakis, N., Siafakas, N., & van der Molen, T. (2011). Factors that influence disease-specific quality of life or health status in patients with COPD: A review and meta-analysis of Pearson correlations. Primary Care Respiratory Journal, 20(3), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00029

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Andrade, C. (2015). The primary outcome measure and its importance in clinical trials. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 76(10), e1320–e1323. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15f10377.

Maher, C. G., Sherrington, C., Herbert, R. D., Moseley, A. M., & Elkins, M. (2003). Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Physical Therapy, 83(8), 713–721.

Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., Welch, V. A. (Editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Cochrane, 2021. Available from https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4. In. (2020). The Cochrane Collaboration.

Van Tulder, M., Furlan, A., Bombardier, C., & Bouter, L. (2003). Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine, 28(12), 1290–1299.

Rabe, K. F., Bateman, E. D., O’Donnell, D., Witte, S., Bredenbroker, D., & Bethke, T. D. (2005). Roflumilast—An oral anti-inflammatory treatment for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 366(9485), 563–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67100-0

Shergis, J. L., Thien, F., Worsnop, C. J., Lin, L., Zhang, A. L., Wu, L., Chen, Y., Xu, Y., Langton, D., Da Costa, C., Fong, H., Wu, D., Story, D., & Xue, C. C. (2019). 12-month randomised controlled trial of ginseng extract for moderate COPD [Journal Article; Multicenter Study; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. Thorax, 74(6), 539–545. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212665

Lipson, D. A., Barnacle, H., Birk, R., Brealey, N., Locantore, N., Lomas, D. A., Ludwig-Sengpiel, A., Mohindra, R., Tabberer, M., Zhu, C. Q., & Pascoe, S. J. (2017). FULFIL Trial: Once-daily triple therapy for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Clinical Trial, Phase III; Journal Article; Multicenter Study; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 196(4), 438–446. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201703-0449OC

Liu, M., Zheng, F., Ni, L., Sun, Y., Wu, R., Zhang, T., Zhang, J., Zhong, X., & Li, Y. (2016). Sugarcane bagasse dietary fiber as an adjuvant therapy for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A four-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study [Journal Article; Multicenter Study; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine = Chung i tsa chih ying wen pan, 36(4), 418–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0254-6272(16)30057-7

Wootton, S. L., Cindy Ng, L. W., McKeough, Z. J., Jenkins, S., Hill, K., Eastwood, P. R., Hillman, D. R., Cecins, N., Spencer, L. M., Jenkins, C., & Alison, J. A. (2014). Ground-based walking training improves quality of life and exercise capacity in COPD. European Respiratory Journal, 44(4), 885–894.

Wootton, S. L., McKeough, Z., Ng, C. L. W., Jenkins, S., Hill, K., Eastwood, P. R., Hillman, D., Jenkins, C., Cecins, N., Spencer, L., & Alison, J. (2018). Effect on health-related quality of life of ongoing feedback during a 12-month maintenance walking programme in patients with COPD: A randomized controlled trial. Respirology, 23(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13128

Duiverman, M. L., Wempe, J. B., Bladder, G., Vonk, J. M., Zijlstra, J. G., Kerstjens, H. A., & Wijkstra, P. J. (2011). Two-year home-based nocturnal noninvasive ventilation added to rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: A randomized controlled trial [Comparative Study; Journal Article; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. Respiratory research, 12, 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-12-112

Heslop-Marshall, K., Baker, C., Carrick-Sen, D., Newton, J., Echevarria, C., Stenton, C., Jambon, M., Gray, J., Pearce, K., Burns, G., & De Soyza, A. (2018). Randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy in COPD. ERJ Open Research. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00094-2018

Jolly, K., Sidhu, M. S., Hewitt, C. A., Coventry, P. A., Daley, A., Jordan, R., Heneghan, C., Singh, S., Ives, N., Adab, P., Jowett, S., Varghese, J., Nunan, D., Ahmed, K., Dowson, L., & Fitzmaurice, D. (2018). Self management of patients with mild COPD in primary care: Randomised controlled trial [Clinical Trial, Phase III; Journal Article; Multicenter Study; Pragmatic Clinical Trial; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 361, k2241. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2241

Wang, G., Liu, B., Cao, Y., Du, Y., Zhang, H., Luo, Q., Li, B., Wu, J., Lv, Y., Sun, J., Jin, H., Wei, K., Zhao, Z., Kong, L., Zhou, X., Miao, Q., Wang, G., Zhou, Q., & Dong, J. (2014). Effects of two Chinese herbal formulae for the treatment of moderate to severe stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 9(8), e103168.

Tonnel, A. B., Perez, T., Grosbois, J. M., Verkindre, C., Bravo, M. L., & Brun, M. (2008). Effect of tiotropium on health-related quality of life as a primary efficacy endpoint in COPD. International Journal of COPD, 3(2), 301–310.

van Wetering, C. R., Hoogendoorn, M., Mol, S. J., Rutten-van Molken, M. P., & Schols, A. M. (2010). Short- and long-term efficacy of a community-based COPD management programme in less advanced COPD: A randomised controlled trial. Thorax, 65(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.118620

Walker, P. P., Pompilio, P. P., Zanaboni, P., Bergmo, T. S., Prikk, K., Malinovschi, A., Montserrat, J. M., Middlemass, J., Šonc, S., Munaro, G., Marušič, D., Sepper, R., Niroshan Siriwardena, A., Calverley, P. M. A., & Dellaca’, C. R. L. (2018). Telemonitoring in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (CHROMED). A randomized clinical trial [Journal Article; Multicenter Study; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 198(5), 620–628. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201712-2404OC

Zarghami, M., Taghizadeh, F., Sharifpour, A., & Alipour, A. (2018). Efficacy of smoking cessation on stress, anxiety, and depression in smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Addiction and Health, 10(3), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.22122/ahj.v10i3.600

Buhl, R., Gessner, C., Schuermann, W., Foerster, K., Sieder, C., Hiltl, S., & Korn, S. (2015). Efficacy and safety of once-daily QVA149 compared with the free combination of once-daily tiotropium plus twice-daily formoterol in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD (QUANTIFY): A randomised, non-inferiority study. Thorax, 70(4), 311. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206345

Chan, A. W., Lee, A., Lee, D. T., Sit, J. W., & Chair, S. Y. (2013). Evaluation of the sustaining effects of Tai Chi Qigong in the sixth month in promoting psychosocial health in COPD patients: A single-blind, randomized controlled trial [Journal Article; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. The Scientific World Journal, 2013, 425082. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/425082

Farmer, A., Williams, V., Velardo, C., Shah, S. A., Yu, L. M., Rutter, H., Jones, L., Williams, N., Heneghan, C., Price, J., Hardinge, M., & Tarassenko, L. (2017). Self-management support using a digital health system compared with usual care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(5), e144. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7116

Gallefoss, F., Bakke, P. S., & Kjaersgaard, P. (1999). Quality of life assessment after patient education in a randomized controlled study on asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 159(3), 812–817. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9804047

Haugen, T. S., & Stavem, K. (2007). Rehabilitation in a warm versus a colder climate in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—A randomized study. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 27(1), 50–56.

Lamers, F., Jonkers, C. C., Bosma, H., Chavannes, N. H., Knottnerus, J. A., & van Eijk, J. T. (2010). Improving quality of life in depressed COPD patients: Effectiveness of a minimal psychological intervention [Comparative Study; Journal Article; Multicenter Study; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. COPD, 7(5), 315–322. https://doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2010.510156

Moy, M. L., Martinez, C. H., Kadri, R., Roman, P., Holleman, R. G., Kim, H. M., Nguyen, H. Q., Cohen, M. D., Goodrich, D. E., Giardino, N. D., & Richardson, C. R. (2016). Long-term effects of an internet-mediated pedometer-based walking program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Randomized controlled trial [Journal Article; Randomized Controlled Trial]. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(8), e215. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5622

Muhamad, R., Draman, N., Aziz, A. A., Abdullah, S., & Jaeb, M. Z. M. (2018). The effect of Tualang honey on the quality of life of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 13(1), 42–50.

Polkey, M. I., Qiu, Z. H., Zhou, L., Zhu, M. D., Wu, Y. X., Chen, Y. Y., Ye, S. P., He, Y. S., Jiang, M., He, B. T., Mehta, B., Zhong, N. S., & Luo, Y. M. (2018). Tai Chi and pulmonary rehabilitation compared for treatment-naive patients with COPD: A randomized controlled trial [Comparative Study; Journal Article; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. Chest, 153(5), 1116–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.053

Pumar, M. I., Roll, M., Fung, P., Rolls, T. A., Walsh, J. R., Bowman, R. V., Fong, K. M., & Yang, I. A. (2019). Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for patients with chronic lung disease and psychological comorbidities undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 11, S2238–S2253. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.10.23

Spencer, L. M., Alison, J. A., & McKeough, Z. J. (2010). Maintaining benefits following pulmonary rehabilitation: A randomised controlled trial. European Respiratory Journal, 35(3), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00073609

Thom, D. H., Willard-Grace, R., Tsao, S., Hessler, D., Huang, B., DeVore, D., Chirinos, C., Wolf, J., Donesky, D., Garvey, C., & Su, G. (2018). Randomized controlled trial of health coaching for vulnerable patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Journal Article; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 15(10), 1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201806-365OC

Wu, M., Zhou, L. Q., Li, S., Zhao, S., Fan, H. J., Sun, J. M., Li, X. N., Luo, J., Wang, A. Q., Wu, J. P., Li, X. Y., & Zhang, J. N. (2018). Efficacy of patients’ preferred exercise modalities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A parallel-group, randomized, clinical trial [Journal Article; Multicenter Study; Randomized Controlled Trial]. Clinical respiratory journal, 12(4), 1581–1590. https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.12714

Xin, C., Xia, Z., Jiang, C., Lin, M., & Li, G. (2016). The impact of pharmacist-managed clinic on medication adherence and health-related quality of life in patients with COPD: A randomized controlled study. Patient Preference and Adherence, 10, 1197–1203.

Coultas, D., Frederick, J., Barnett, B., Singh, G., & Wludyka, P. (2005). A randomized trial of two types of nurse-assisted home care for patients with COPD. Chest, 128(4), 2017–2024. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.128.4.2017

Ferrone, M., Masciantonio, M. G., Malus, N., Stitt, L., O’Callahan, T., Roberts, Z., Johnson, L., Samson, J., Durocher, L., Ferrari, M., Reilly, M., Griffiths, K., & Licskai, C. J. (2019). The impact of integrated disease management in high-risk COPD patients in primary care. NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine, 29(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-019-0119-9

Hynninen, M. J., Bjerke, N., Pallesen, S., Bakke, P. S., & Nordhus, I. H. (2010). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in COPD. Respiratory Medicine, 104(7), 986–994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2010.02.020

Jarab, A. S., AlQudah, S. G., Khdour, M., Shamssain, M., & Mukattash, T. L. (2012). Impact of pharmaceutical care on health outcomes in patients with COPD. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 34(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-011-9585-z

Jonsdottir, H., Amundadottir, O. R., Gudmundsson, G., Halldorsdottir, B. S., Hrafnkelsson, B., Ingadottir, T. S., Jonsdottir, R., Jonsson, J. S., Sigurjonsdottir, E. D., & Stefansdottir, I. K. (2015). Effectiveness of a partnership-based self-management programme for patients with mild and moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(11), 2634–2649. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12728

Khdour, M. R., Kidney, J. C., Smyth, B. M., & McElnay, J. C. (2009). Clinical pharmacy-led disease and medicine management programme for patients with COPD. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 68(4), 588–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03493.x

Linneberg, A., Rasmussen, M., Buch, T. F., Wester, A., Malm, L., Fannikke, G., & Vest, S. (2012). A randomised study of the effects of supplemental exercise sessions after a 7-week chronic obstructive pulmonary disease rehabilitation program. Clinical Respiratory Journal, 6(2), 112–119.

McGeoch, G. R., Willsman, K. J., Dowson, C. A., Town, G. I., Frampton, C. M., McCartin, F. J., Cook, J. M., & Epton, M. J. (2006). Self-management plans in the primary care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Journal Article; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov’t]. Respirology (Carlton, Vic.), 11(5), 611–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00892.x

Tupper, O. D., Gregersen, T. L., Ringbaek, T., Brondum, E., Frausing, E., Green, A., & Ulrik, C. S. (2018). Effect of tele-health care on quality of life in patients with severe COPD: A randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 13, 2657–2662. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S164121

Wong, E. Y., Jennings, C. A., Rodgers, W. M., Selzler, A. M., Simmonds, L. G., Hamir, R., & Stickland, M. K. (2014). Peer educator vs. respiratory therapist support: Which form of support better maintains health and functional outcomes following pulmonary rehabilitation? Patient Education and Counseling, 95(1), 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.12.008

Ma, R. C., Yin, Y. Y., Wang, Y. Q., Liu, X., & Xie, J. (2020). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 38, 101071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.101071

Kruis, A. L., & Chavannes, N. H. (2010). Potential benefits of integrated COPD management in primary care. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease, 73(3), 130–134. https://doi.org/10.4081/monaldi.2010.297

Arch, J. J., & Stanton, A. L. (2019). Examining the “usual” in usual care: A critical review and recommendations for usual care conditions in psycho-oncology. Support Care Cancer, 27(5), 1591–1600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04677-5

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by National Key R&D Program of China (Grand No. 2020YFC2008502) and the Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan Province (Grant No. 2019YJ0119).

Funding

The study was funded by National Key R&D Program of China (Grand No. 2020YFC2008502) and the Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan Province (Grant No. 2019YJ0119).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ZL and QW; Methodology: QW, CF, and RL; Formal analysis and investigation: RL, CF, and QW; Writing—original draft preparation: ZL; Writing—review and editing: QW, LW, GP, and LX; Funding acquisition: QW; Resources: CH; Supervision: QW.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, Z., Wang, Q., Fu, C. et al. What conservative interventions can improve the long-term quality of life, depression, and anxiety of individuals with stable COPD? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res 31, 977–989 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02965-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02965-4