Abstract

Martin Luther King Jr. claimed that “the salvation of the world lies in the hands of the maladjusted”. I elaborate on King’s claim by focusing on the way in which we treat and understand ‘maladjustment’ that is responsive to severe trauma (e.g. PTSD that is a result of military combat or rape). Mental healthcare and our social attitudes about mental illness and disorder will prevent us from recognizing real injustice that symptoms of mental illness can be appropriately responding to, unless we recognize that many emotional states (and not just beliefs!) that constitute those symptoms are warranted by the circumstances they are responsive to. I argue that there is a failure to distinguish between PTSD symptoms that are warranted emotional responses to trauma and those that are not. This results in us focusing our attention on “fixing” the agent internally, but not on fixing the world. It is only by centering questions of warrant that we will be able to understand and expose the relationship between agents’ internal mental states and their oppression. But we also need to ask when someone’s emotional response is unwarranted by their experience (as in the case of someone who develops PTSD after a non-traumatic event). If we fail to do this—as, I claim, both our mental healthcare and the broader social world fail to do—we treat warranted and unwarranted emotions as on a par. This undermines the epistemic judgment of the agent who has warranted PTSD symptoms, resulting in her failing to trust her evaluation of whether her emotional response to her own trauma is warranted by that trauma, and thus failing to recognize her own oppression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In a speech delivered to faith leaders in 1957, Martin Luther King Jr. said:

There are certain technical words in the vocabulary of every academic discipline which tend to become clichés and stereotypes. Psychologists have a word which is probably used more frequently than any other word in modern psychology. It is the word “maladjusted.” This word is the ringing cry out of the new child psychology—“maladjusted.” Now in a sense all of us must live the well-adjusted life in order to avoid neurotic and schizophrenic personalities. But there are some things in our social system to which I’m proud to be maladjusted and to which I call upon you to be maladjusted. I never intend to adjust myself to the viciousness of mob rule. I never intend to adjust myself to the evils of segregation or the crippling effects of discrimination. I never intend to adjust myself to an economic system that will take necessities from the masses to give luxuries to the classes. I never intend to adjust myself to the madness of militarism and the self-defeating effects of physical violence. And my friends, I call upon you to be maladjusted to all of these things, for you see, it may be that the salvation of the world lies in the hands of the maladjusted (2007, 326).

King’s claim is an important insight into how we think about the relationship between mental illness, injustice, and, at a much broader level, the relationship between individual agency and the social world. My goal is to put some more detailed meat on the bones of King’s claim, as well as applying it to today’s social world, by examining ways in which mental illness, injustice, and warrant interact.Footnote 1

I focus on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as pathologized maladjustment. My arguments do not generalize neatly, though they extend naturally to thinking about some mental illnesses (e.g. depression) and less so to others (e.g. schizophrenia). I focus on PTSD because it provides insight into the positive project of amelioration with respect to our concepts of specific mental disorders and illnesses, and because it has a clear environmental-social contribution; indeed, it is often directly responsive to systematic social injustice, e.g. rape or war.

I argue for two related theses. The first has two pieces. First, some trauma reactions that get diagnosed as PTSD are important guides to structural injustice (such as the injustice of sending people to combat zones to fight unjust wars, or rape as a social-structural problem), and our lack of recognition that the agent is warranted in many of her PTSD symptoms serves to wrongly focus our attention exclusively on internal problems with the agent.Footnote 2 Second, there is an important contrast between these kinds of cases and PTSD diagnoses that are triggered by minor interpersonal or personal harm that is not a part of a social-structural problem (for example, losing some money on the stock market while remaining in the 1%). If we don’t treat these cases differently, we won’t be able to distinguish between whether we should try to change the conditions that caused the PTSD, alongside trying to help the agent internally, or whether we should solely attempt to help the agent internally. Thus, the first thesis is: we must not only center warrant, in thinking about mental disorder, but also must center lack of warrant. The second thesis directly connects this up to King’s claims: our lack of focus on warrant serves to systematically obscure oppression and injustice: when our (partly) warranted reactions to trauma are treated as internal problems with us as agents, and when our warranted negative emotional and physiological responses to oppression and injustice are treated as no different from the negative emotional responses to minor, non-systematic personal harm, it is extremely difficult to see ourselves as reacting to something systematically unjust.

The broader upshots here is that, first, we are too focused on desirability norms (focused on being in mental states that are desirable for us) and not focused enough on norms about warrant (focused on being in mental states that are warranted by the circumstances they are responsive to). And, second, this focus on desirability at the expense of warrant exacerbates and obscures oppression. This claim provides support for King’s claims, as well as related claims from Sarah Ahmed (2010, 2015), James Baldwin (1961), Cherry (2018, 2020), Frantz Fanon (1963), Lorde (1980, 1981, 1984), Tessman (2005), Malcolm (1964), Rankine (2015, on mourning) and Srinivasan (2018). But it also helps us think about the interaction between oppression and mental illness in distinctive ways.

I focus on the United States, where I think these issues are particularly pronounced, in part due to our robust ideology of individualism, which helps dictate the dominant cultural ideas—the dominant ideology—about warrant, desirability, and mental health, informed, in some ways, by mental health experts. The U.S. is neither culturally nor ideologically monolithic, and not everything I have to say will apply to non-dominant social practices, norms, culture, and so on.

In Sect. 1, I lay out a few background assumptions and starting points. In Sect. 2, I discuss two ways in which mental illness and health interact with structural injustice which are not my own, but which are connected. In Sect. 3, I provide a starting case, as well as lay out how PTSD is defined and thought about. In Sect. 4, I make further clarifications about warrant and desirability. In Sect. 5, I address what the harm is in the starting case, and then expand outwards to show why it is a general problem that obscures our ability to recognize and fight back against our own oppression. In Sect. 6, I extend Sarah Paul’s (2019) argument about imposter syndrome to PTSD. I conclude in Sect. 7 by offering some thought experiments that motivate the importance of warrant in evaluating PTSD.

2 Some background

I focus on directed emotional states. These are emotional states that are intentional, and are at least vaguely directed at some circumstances, act, event, etc. (They need not be propositional attitudes, since their object needn’t be articulable as a proposition.) Most of our emotional states are directed emotional states, for example, my being angry that I lost five dollars; the kinds of emotional states that are excluded are feeling a general sense of malaise, sadness, manic happiness, general moods, etc. that are not experienced as directed at anything at all. But even a state like being depressed in a way that is vaguely directed at injustice in the world, or at one’s own circumstances broadly understood, counts as a directed emotional state.

I assume that there is a conceptually important distinction between warranted (or “apt” or “fitting”) and desirable directed emotional states. Here I follow many philosophers, but especially Nomy Arpaly (2005), whose paper sets the stage for my own.Footnote 3 Arpaly argues that treating mental illness just like physical illness is both morally and conceptually fraught, precisely because it misses out on the fact that mental states can be warranted and unwarranted, but physical states cannot. Related claims are also present in the psychiatry and philosophy of psychiatry literature. For example, Durà-Vilà and Dein argue that it is important for us to find our own psychological suffering meaningful, and that when psychiatrists assimilate mental disorder to physical illness, they seem to close off that possibility (2009, p. 557).Footnote 4

My concept of warrant differs importantly from Arpaly’s; it is closer, in some ways, to ideas about “fittingness” of emotions. Arpaly takes warrant roughly to be truth-tracking (2005, 283). Warranted directed emotional states are states that correctly match emotions to their objects. They track and respond to our evidence and to reality, as it is presented to us.Footnote 5 I treat warrant for directed emotional states as playing similar role to what justification plays for our beliefs. So warranted mental states needn’t be directed at propositions or circumstances that correctly track reality if reality is obscure to us; instead, they need to be properly responsive to the world as it is presented to us.Footnote 6 Thus someone can be in a warranted directed emotional state, say, frustration with herself for losing five dollars, even if in fact the five dollars was stolen from her (and thus it is neither quite true that she lost five dollars, nor would frustration with herself be warranted if she knew the truth).Footnote 7

The facts about what responses are warranted are objective—it is never warranted to react with callous humor to becoming aware of a horrific death.Footnote 8 But warrant is subjective in the sense that directed emotional states involve both an object of some kind and an emotion directed at that object, and we both can be wrong about those objects, and will, of course, have distinct experiences, presenting us with distinct objects. And our circumstances help determine which matches between emotions and objects are appropriate. As a relatively wealthy person, I am not warranted in being deeply frustrated that I lost five dollars, even when my belief that I lost five dollars is justified. Someone living in poverty would be warranted in this response.

Desirable mental states are, roughly speaking, those that we want to have. This might be cashed out in terms of thinking about what is good for us as individuals. But it is important to note that desirability does not (necessarily) track philosophers’ notions of wellbeing. Desirability is not a philosophical notion; it is an attempt to capture a kind of ordinary social normativity that corresponds to our ordinary concept of what serves our emotional interests as individuals. It’s important to note that philosophers and psychiatrists/psychologists alike acknowledge that it is a deliberate choice of the DSM to focus on (roughly) desirability: the DSM focuses on an operational/reliable set of criteria, but what it is reliable for is diagnosing failures of functionality, of feeling good, and so on.Footnote 9

I want to flag, though, that while I treat desirability and warrant as wholly conceptually distinct in what follows—an intentional choice in order to be able to clarify the conflict between them and the need to focus on warrant when we think about mental illness—I suspect that our actual social norms here are messier, and more entwined, than I make them out to be.

I think, following some others, that at least for some negatively-valenced emotional mental states, including some of those that might seem undesirable for us, them being warranted (or “apt”) is reason enough for us to have them—that they don’t need to serve a prudential or moral role.Footnote 10 While many take this as (somewhat) obvious for belief, there is less consensus when it comes to directed emotional states like being angry that I was fired.Footnote 11

In the philosophy of psychiatry literature, there has been significant focus on the relationship between belief (and belief-like states), delusion, rationality, and desirability. For example, Bortolotti has done important work on distinguishing delusions from irrational belief (e.g. 2020). Radden (2011), whose arguments I am sympathetic to, has argued both that what we count as delusional is a foil for the development of modern epistemology (p. 1), and that this is tied up with the idea that (roughly) what we count as delusion is heavily cultural (for example, certain religious beliefs aren’t counted as delusional despite in many ways seeming to have the right status to do so). And recent discussion of confabulation and its functional role in our lives are also tied up (implicitly) with questions of justification vs. desirability.Footnote 12

Importantly, though, all of these authors are focused on beliefs (or belief-like states), and the relationship between either justification (or something like it), pragmatics, the social/cultural, or the function of belief; I am here focused on emotions and their warrant (or fittingness), not beliefs. The issues are distinct in part because our norms for belief are (even in the “post-truth” era) more strongly tied to justification than our norms about emotion are tied to warrant. Further, warranted emotions seem to be more directly bad for us, desirability-wise, than justified beliefs. And, most importantly, mental health professionals tend to believe in constraints on rationality and justification, of some kind, for belief; if they didn’t, given that the DSM aims at desirability, we’d be awash in people being encouraged by their therapists and psychiatrists to believe—even systematically—against the evidence. (Indeed, some of the literature mentioned above is focused on treating a certain class of beliefs as “epistemically innocent”, but this wouldn’t be a concern to take up if we didn’t take there to be serious epistemic constraints on belief.) It is much less clear that mental health professionals tend to believe that emotions are even the kinds of things that there are epistemic constraints on.

Finally, I assume that while mental illness and health are real phenomena, both the boundaries of mental illness generally and the definitions of particular mental illnesses are at least partly socially constructed. (The chair of the DSM-IV task force, Allen Frances, agrees: see Frances and Widiger (2012).) Clinical ideas about mental illness often differ from general social ideas about mental illness. Social concepts of mental illness (“folk psychiatry”) are constructed by communities of people, with the most influence coming from those with significant power and stakes in these matters (in both negative and positive ways; e.g. well-meaning psychiatrists and psychologists whose aims are to help their patients and the general public, but also, e.g., pharmaceutical companies, whose aims are generally simply to make money). Clinical concepts (“professional psychiatry”) come from some messy combination of the DSM and actual clinical practice, but also are influenced by the social world. The metaphysical underpinnings of mental illness—the boundaries of how far the social construction aspect of mental illness and health reach, and whether there are underlying natural kinds at stake—are not central here, and I will leave them vague, though I note that here I likely don’t disagree, at the broad level, with general views in professional psychiatry that diagnostic categories don’t tend to correspond to natural kinds but rather to pragmatically useful concepts.Footnote 13 I am also sympathetic to Hanna Pickard’s (2009) argument that discovering brain abnormalities that correspond to particular symptoms of mental illnesses does not settle anything about the nature of the mental illness or disorder itself, which essentially involves psychosocial norm violation.Footnote 14

But centrally, I want to emphasize: this is not a paper about the metaphysics of mental disorder, though what I say has important implications for conceptually clarifying mental disorder. I don’t need anything but the assumption—an assumption which is shared by very many—that even if there are natural kinds at stake when it comes to mental illness and health, our concepts—both folk-psychiatric and professional-psychiatric—are at least partly socially constructed. And it is the relationship between the social world, our warranted emotions, and injustice that this paper is about.

3 Mental illness and structural injustice

There are two important ways that mental illness interacts with structural injustice that are not my focus. First, at a very general level, there is significant bias against, stigma surrounding, and poor treatment of mentally ill people. Second, there is extreme inequity along race and class lines both about how mental illness is treated and about whether it is even diagnosed or treated as mental illness.

The rapper Meek Mill sums the second point up well:

Philadelphia Murder rate has been in the 300 murders plus range since I can remember and kids are growing up in that first hand and they have no choice but to carry firearms after seeing all that blood spilled and that will distort your decision making process like PTSD (2019)

You get locked up wit a gun you can’t go to court and say you got PTSD from seeing too much murder (2019).

Meek Mill is highlighting two injustices: first, PTSD diagnoses are unavailable to many poor, black, and brown people. In part this is due to a lack of health care resources and stigmatization around seeking mental health care. But there is more to it than this: one of the things that Meek points out is that severe trauma distorts the way people think about danger, decisions, our impulse control, and so on, but that the very real trauma of living under these kinds of conditions is not itself treated as the sort of thing that we should expect to produce an epidemic of PTSD (whereas, as I will later discuss, wealthier white people receive PTSD diagnoses after experiencing “trauma” such as losing portions of their wealth while still living extremely comfortably). This leads to Meek’s second claim: mental illness is not treated as exculpatory for those who are oppressed along race and class lines, even when, in the case where the disorder is partly environmentally caused (as in PTSD), the environment is rife with the sorts of traumas that trigger PTSD.

My argument is connected to, and has implications for, this point. By focusing on the manifestation of undesirable mental states, we lose sight of the experiences of the agent-world interaction that warrants those mental states. This plays out differently in different contexts; but in many contexts in the US, we have lost sight, when thinking about partly environmentally caused mental illness and disorder, of the importance of the role of warrant.Footnote 15 Without distinguishing between warranted and unwarranted directed emotional states, we can’t properly recognize our own oppression: it is at best obscured and at worst reinforced by the focus on desirability. Our social norms emphasize the importance of desirability of our mental states, and de-emphasize the importance of warrant of our mental states, in part because this supports structural injustice: we can’t “know it when we see it” if we are normatively stripped of the tools for recognizing it, focused internally on our own pain and what is wrong with us, rather than externally on the injustice itself.

4 PTSD

King’s quote reminded me of a conversation that one of my friends (I’ll call her ‘Dominique’), irate about what had happened to her in a recent therapy session, recounted to me just after the 2008 financial crisis. The conversation went something like this:

-

Dominique It is so unreasonable for me to have these psychological reactions to experiences I had long ago that aren’t that bad. (Dominique is grasping at pro-warrant norms after being subjected, by many different mental health professionals, to a constant battery of pro-desirability norms.)

-

Therapist No, it’s not unreasonable. Different people react to different kinds of things differently, and react to trauma differently. And different people experience different things as trauma. I have a client, Chip, who is suffering from PTSD because his large trust fund is down to under half of what it was.

-

Dominique Am I supposed to be comforted by the idea that people like Chip, who have no idea what real suffering is like, are experiencing similar mental health problems to me? This only makes me feel worse: not only is what I am experiencing unreasonable, but you are assimilating it to the experience of someone whose emotional states are extremely unreasonable.

I’ve long tried to figure out exactly what was wrong with Therapist’s side of this conversation. Different people do react to trauma differently, and also experience different things as trauma. And if people really are experiencing symptoms that look like PTSD symptoms in response to events like losing half of one’s wealth while remaining in the 1%, it is not as if they are not deserving of resources for coping with those symptoms. (And, it may be, as Frances and Widiger (2012) discuss, that when it comes to mental illness, if it walks like a duck…) Still, Dominique’s outraged response was exactly correct. Let’s begin to attempt to unpack why that is.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is defined by the DSM-V as comprising four clusters of symptoms:

-

Intrusive/recurrent memories of trauma

-

Avoidance of trauma-related stimuli

-

Negative changes of mood or cognition and/or numbing of mood and/or cognition

-

Pertaining to the trauma

-

Changes in reactivity and arousal. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

The DSM-V also includes specific requirements for what counts as trauma (involving either knowing about or being exposed to serious sexual or physical violence or harm). Thus it looks like it attempts to give an objective account of what the symptoms of PTSD must be triggered by or responsive to. It may be that “concept creep” is at play in how PTSD is being diagnosed, since Chip’s case is not unique; for example, a number of my students have told me that they have been diagnosed with and treated for PTSD where the triggering trauma, while more serious in various ways than Chip’s, does not meet the DSM-V criteria.Footnote 16 That concept creep is certainly at play in the broader social milieu, where things are constantly labeled ‘PTSD’ that are even more minimal than Chip’s trauma, e.g. a student’s response to a difficult exam, or an instructor’s response to dealing with a difficult student.

I suspect that if PTSD is overdiagnosed relative to the diagnostic criteria in the DSM-V, this is partly explained by the fact that, because of the earlier-mentioned intentional move towards operationalizing and reliability over validity and a search for natural kinds, for most mental illnesses, there is no more to their epistemology than their symptoms.Footnote 17 If symptoms look similar, and seem treatable in the same way, then it makes sense that it is subjective experience of an event as traumatic that matters, not whether that event meets the requirements for counting as trauma. Perhaps, then, mental health professionals are right not to focus on whether that experience meets the definition of trauma in the DSM-V.

This is connected to Arpaly’s observation that “psychiatrists think of mental disorders primarily as ‘‘maladaptive’’ mental states, or states that cause ‘‘impairment’’ or ‘‘distress’’: in other words, they think of mental disorders primarily as undesirable mental states, the way that diabetes is an undesirable non-mental condition.” (2005, 284). Given my concept of warrant, I can say something stronger. A collaborator recently mentioned that her therapist had told her that there is no such thing as an unwarranted emotional state; that emotional states are just physical states of our body and that it “doesn’t make sense” to ask if they are correctly responding to the world. This concurs with my own experience with mental health professionals: many of them think that there simply isn’t a further question of warrant when it comes to directed emotional states, because they aren’t the sort of thing that are apt for evaluation as warranted or unwarranted—that is, they reject one of the starting assumptions of my paper. If warrant is not even in play, then it is hard to see why it would matter what event or circumstances one’s PTSD-like symptoms were responsive to, so long as there was a subjective connection between it and one’s undesirable mental states—one’s PTSD-like symptoms.

What is motivating this rejection of warranted emotions? One possible motivation (though one I think is wrongheaded) is elaborated by Steven Gubka (2021), who argues that emotions can’t be the kinds of things that are evaluated for rationality, because we engage in emotional regulation and distortion (medication, going for a run, etc.) that don’t provide us with reasons for shifting our emotions but nevertheless are not irrational. Because emotions are things we manage, not with reason but with medication, therapy, self-care, etc., it doesn’t make sense to evaluate whether our emotions are warranted.

Perhaps, though, mental health professionals have a different (but related) philosophical view here: they think, along with many philosophers, that it is only beliefs that represent reality, whereas our emotions, while they often help shape our beliefs, don’t themselves represent reality. If so, it is only our beliefs that are correct or incorrect with respect to representing reality. So what matters, from a justification/warrant perspective, is whether I am right that I lost five dollars. (Arpaly’s concept of warrant seems to have this implication.) If my anger that I loss five dollars doesn’t aim at representing reality, perhaps it is not evaluable in the same way as my belief that I lost five dollars.

I don’t have the space to argue against these views here. I remind my reader that I am assuming that directed emotional states are warranted and unwarranted. But my argument does (indirectly) motivate that assumption. There is something importantly different between Chip and Dominique, that is neither reducible to the rationality of their beliefs nor to a specifically moral problem with either their beliefs or their emotions. If we don’t attend to that difference, we risk being unable to recognize oppression and injustice. If failing to evaluate them as warranted or unwarranted leads to Chip and Dominique’s situations being treated as on a par, then it is crucial that we correct that.Footnote 18

Crucially, I do not deny that PTSD is bad for those who have it. It can lead to suicide, violence against others, dissociation, personality disorders, addiction, and vulnerability to re-traumatization. PTSD puts people in all sorts of undesirable mental and physiological states.

But are those mental states warranted? It’s complicated: they certainly never all are, in anyone who suffers from PTSD. PTSD typically involves some immediate physiological states, like hyperarousal, that arguably don’t even rise to the level of emotions or directed emotional states and thus aren’t even apt for this kind of evaluation. Further, many non-physiological symptoms of PTSD may not be warranted either. However, some people who have undergone long-term, inescapable trauma (combat soldiers; people in abusive relationships; those living under violence and poverty in urban America; children who are abused by parents, etc.) also are warranted in having many—perhaps even most—of their symptoms. And, my claim is, it is urgent that we separate those with almost entirely unwarranted symptoms (like Chip) from those with many warranted symptoms, like Dominique (who underwent seemingly inescapable long-term trauma, including systematic violence and death threats), are. This doesn’t mean—and I will return to this later—that there might not be preferable sets of warranted reactions to trauma. Perhaps these would involve not suffering from some of the symptoms of PTSD, but retaining others, or simply reacting with anger and sadness, but not with any symptoms of PTSD. Still, serious trauma does warrant many (not all) of PTSD’s symptoms.

One common cause of PTSD is being subjected to extensive domestic violence. People who have justified beliefs that they do not have other options or cannot escape their situation often develop c-PTSD (depending on who you ask, either a particularly acute form of PTSD, or a distinct disorder). In turn, such people may develop at least some emotional responses to certain stimuli that are warranted by what they know and what they can reasonably expect. Their background knowledge and expectations are different from those who have not had their experience. They have learned different things than the rest of us about what kinds of situations are dangerous, when to be on alert, and so on. And their learning tracks their evidence about reality! Insofar as our warranted emotional responses can be warranted by inductive learning about our social and personal environments (just as our justified beliefs can be), victims of long-term domestic violence are being properly responsive to the world when they feel that they are in danger, even if they have escaped the particular violence that they suffered. The social world and our position within it helps determine whether our directed emotional states are warranted, because the social world and our position within it helps determine what our environment looks like, what our evidence is, and what we should inductively reason and learn on the basis of, as well as which emotional responses are warranted by which circumstance.Footnote 19

In cases of long-term, inescapable trauma, our social mechanisms for learning are either prevented from being exercised or are distorted. Soldiers are trained not to have warranted emotional reactions to either witnessing the death or dismemberment of their compatriots, or to themselves killing and injuring others; they are also trained not to have warranted reactions to the contemplation of their own deaths. This is a social process; it distorts and shapes social learning. And acknowledging it supports the idea that it is only once soldiers, or people who were sexually or physically abused, re-enter the broader social world, and engage in social learning about the reality of their own experience, that they can deploy the warranted reactions to their trauma. One way to do that is to “relive” the trauma via memories and flashbacks, experiencing a more apt set of emotions and beliefs aimed at it. Thus, I claim, even delayed experiential symptoms of PTSD may be warranted in cases where they are directed emotional responses to past, but severe, trauma. This may initially seem implausible. But there are further considerations that support it.

First, we often delay in allowing ourselves to experience the appropriate directed emotional states toward, e.g., grieving the loss of a parent or a child. But if someone does prevent themselves from grieving in the short run, mental health professionals often encourage this delayed grieving. And this is reflected in the general social milieu, including in pop culture. In the 2021 miniseries Mare of Easttown, Mare begins therapy two years after her son commits suicide, and her therapist pushes her towards allowing herself to grieve his death. Mare’s delayed grieving is self-imposed; it is too painful to face her son’s death, so she initially doesn’t allow herself to have the emotional responses that the loss of her child warrant.Footnote 20

If, as Martha Nussbaum (2001, 82) claims, one of the reasons we have for our grieving waning over time is that we adjust to the loss we are grieving, and if delayed grief involves not allowing ourselves to adjust to the loss we are grieving, then it makes sense that delayed grief would be both intense and warranted. Similarly, we might think that our emotional reactions to trauma should be (in the warrant sense) intense when delayed, because there has been no period of adjustment to the trauma.

Further, the analogy between justification, for beliefs, and warrant, for directed emotional states, tells in favor of my view here. Suppose that I, a flat-earther, fail for years to believe on the basis of my extremely strong evidence that the earth is roughly spherical. Then I spend a year without being exposed to any further evidence of the earth’s sphericity, but for some reason, at the end of the year, I come to believe that the earth is spherical on the basis of all of my previous evidence. While I initially made an epistemic mistake, I have now rectified that mistake, and am now doing the (epistemically) correct thing.

That is to say: we don’t think there is something wrong, beyond initial lack of belief, with someone who initially fails to believe p, but is justified in believing p, and then later comes to believe p not on the basis of further evidence, but because they realized they were justified all along. We don’t think that merely because there is a delay, it would be better (rationally speaking) for that person to not come to believe p at all. Delayed formation of a belief based on earlier evidence is (significantly!) better (rationally speaking) than never forming that belief, if our evidence strongly justifies that belief. So, there is a prima facie case for the corollary being true for warrant and directed emotional states. The analogy is imperfect—for example, if emotions are processes and beliefs are not, complications arise—but it is suggestive.Footnote 21

Perhaps we should understand flashbacks and intrusive memories of trauma as playing a similar role, with respect to our directed emotional states, as calling earlier evidence to mind does in justifying our delayed beliefs. In typical cases, I need to call to mind some of my earlier evidence in order to form my delayed belief (indeed it might be irrational to form the delayed belief without being aware of the evidence). Similarly, I claim, we need to call the earlier experience of trauma to mind—to both reconceptualize and re-experience it—in order to have a warranted directed emotional response to it.

Marušić (2018, 2022) points out that reasons for grief don’t seem to expire, and so if the reason for his grief is that his mother has died, it doesn’t seem fitting for him to cease grieving (2018, p. 4). Indeed, the sorts of reasons I have for ceasing grieving seem like paradigmatic “reasons of the wrong kind” in Pamela Hieronymi’s (2005, 2013) sense.

The fact that I have to carry on with my life… is a reason of the wrong kind; it merely shows that it would be important for me not to grieve. Also, it may explain why I experience less grief—why my attention shifts from my mother to other matters—but it does not provide a reason for the diminution of grief. (Marušić, 2018, p. 4.)

Marušić’s puzzle (why, given all this, do we cease grieving?) seems to apply to our case in a slightly different way: if our reasons don’t expire, then it is more appropriate to recognize them and grieve after a multi-year delay than to either recognize them many years after they initially present themselves, but not grieve on the basis of them, or to neither recognize them nor grieve on the basis of them.Footnote 22Footnote 23

Marušić himself rejects the “hardline” view that these kinds of reasons never expire. His rejection is partly motivated by a claim that “persistent” grief counts as a mental disorder: “…If the hardline view were correct, persistent grief would not be a mental disorder but the rational response to a loss.” (2018, p. 9; see also 2022, ch. 3). But if Arpaly and I are correct that mental health professionals’ understanding of mental disorders and illnesses largely have to do with desirability—which lines up with reasons of the wrong kind, in this case—this argument against the hardline view is off-base; it amounts to a claim that if the hardline view were correct, persistent grief would not be desirable for us but would be the rational response to a loss. And that is just to re-state that we have reasons of the right kind (my mother’s death) to continue grieving, and only reasons of the wrong kind (it would be easier for me to move on) to cease doing so.

I agree, though, with Marušić’s more general claim against the hardline view: that it gives us an unrealistic moral psychology. (The hardline view, in my framework, would amount to letting warrant norms swamp desirability ones.) But thinking about grief in terms of social norms about warrant and desirability, as I want to, rather than as being a project in moral psychology, does not present us with the same puzzle; on my view, our understanding of our own emotional responses is powerfully shaped by social norms and social learning; our norms, ideology, and systems of rewards and punishments, not by whatever it means to be an individually rational agent. We have more in common than not, though: Marušić, like me, wants to focus on the object of the grief (or trauma) rather than re-focusing the attention on the individual, and we are interested in similar tensions between desirability and warrant. In Marušić’s framework, we can’t reconcile this tension because desirability gives us reasons of the wrong kind, and warrant gives us reasons of the right kind. I agree that the tension is deep, but I do think that we can weigh desirability and warrant against each other, because I locate the strength and shape of desirability and warrant norms in the social rather than in individual moral psychology.

To sum up: while in no case are all symptoms of PTSD warranted, in cases where someone has experienced serious trauma, especially when that trauma is extended over a long period of time, many of those symptoms are warranted. That neither entails that they are desirable for us nor, as D’Arms and Jacobson (2000) argue about similar cases, the morally correct things to feel (or be motivated to act on the basis of). Nor does it entail that it is best, in any sense, for us to continue experiencing them—that is, that their warrant trounces their undesirability (and, if they are morally bad, their moral badness).Footnote 24 But their warrant matters, and matters deeply—it matters deeply to our social world, to critiquing ideology, and to reconsidering our social norms. We must distinguish, in the mental health context, between warranted emotions and unwarranted ones.

5 A bit more on warrant and desirability

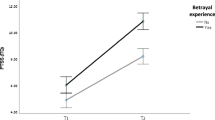

Arpaly (2005) argues that warrant and desirability sometimes conflict. For those who have recently undergone serious traumas like deployment to a combat zone, living in a combat zone, domestic abuse, or rape, warrant and desirability systematically conflict: because there simply aren’t very many positively-valenced directed emotional states that are warranted by their experience, warranted directed emotional states will rarely be desirable for them, and vice-versa.Footnote 25

Chip and Dominique’s treatment by therapist is anecdotal, but suggests that our social and psychosocial norms are too focused on desirability and not focused enough on warrant. I haven’t fully argued for this here, of course—and it must be tempered by the observation that these norms function differently in different contexts. But the idea that only desirability matters is the sort of thing you hear, especially from therapists, all the time.

Whether I am right (generally speaking) that our psychosocial norms push us towards desirability and away from warrant is a partly empirical question. But I believe it should be expected because it is an important piece of the ideology of robust individualism. Pro-warrant norms are inflexible in that, whatever their shape, they essentially focus our attention on the relationship between the agent and the world—because they have to do not just with an agent’s internal states, but with how she understands the external world. Desirability is more flexible because it allows for, in the extreme, solipsism: it doesn’t essentially tie us to others or the external world. Thus, it makes sense that, wielded by an ideology of individualism, our current pro-desirability norms focus most of our attention on an agent and her internal states: this leads us to see her as an isolated individual whose agency is not impacted by or shaped by the world, thus serving to reinforce the idea that we are all self-made individuals, whose successes, failures, poverty, wealth, and so on are entirely due to our individual agency, and have nothing to do with the relationship between us and the broader social world, social systems, and structural injustice.

One might object: we can easily imagine a world in which our pro-desirability norms centered on a different way of thinking about what was desirable for us—e.g. a world shaped around pro-desirability norms based on communitarian ideology. And in such a world, of course, strong pro-desirability norms wouldn’t reinforce individualist ideology. So it’s not pro-desirability norms themselves that are the problem, it’s our hyper-individualist ideology. I agree with this objection, and will use it to clarify that this paper is an exercise in “non-ideal” theory: I’m concerned with the social norms we actually have, and how they reinforce injustice in our non-ideal world. A different paper would start by trying to construct utopian concepts of wellbeing and warrant.

So, I claim, it is no accident that when we lose sight of warrant, we lose sight of the central importance of the external objects of our mental states—of what they are directed at and responsive to. Our negatively-valenced warranted directed emotional states are often directed at structural injustice or instances of it. Focusing on pro-desirability norms—as they currently stand—makes that drop out of the picture. This is exactly what King was concerned about, and is the extension of a point made in various places, but perhaps most clearly by Srinivasan (2018) and by Arpaly, who notes: “For those who value justice, life in a starkly unjust society can be, well, depressing.” (2005, p. 287).

Let’s return to Chip and Dominique’s case. Dominique has many warranted mental states. She also has may have some mental states that might have been warranted in her past circumstances, but are no longer. Chip, on the other hand, is not warranted in having those mental states; he hasn’t actually been in any circumstance in which his PTSD symptoms are properly responsive to their objects. Why aren’t Chip’s PTSD-symptomatic mental states warranted? For the same reason that I’m not warranted in being deeply frustrated with myself for losing five dollars. Chip’s mental states aren’t quite as unwarranted as he would be if he were grieving the loss of one of his fingernail clippings from his body for years on end; there is something that happened to him that some amount of negative emotion is appropriate to, and that needs to be processed and dealt with. He did not, however, undergo trauma, any more than someone who finds themselves traumatized by losing their fingernail clippings did. I don’t take myself to have defended, beyond these analogies, that Chip isn’t warranted in his directed emotional states; recall that I am assuming that there are simply apt and inapt, or warranted and unwarranted, emotions as responses to various circumstances. With that assumption in hand, Chip might be warranted in certain negatively-valenced directed emotional states towards his financial loss, but not the extreme, persistent, and damaging ones that are manifested in PTSD.

None of this is to deny that Chip and Dominique might be in equally undesirable mental states. As I mentioned in Sect. 1, if desirability has to do with wellbeing—if to be in desirable mental states is to be in states that contribute to one’s overall wellbeing—then it may be complicated whether we can say that Chip and Dominique are in equally undesirable mental states, because it depends on our theory of wellbeing. Some theories of wellbeing have something like warrant built into them. (E.g. Feldman, 2004.) However, these theoretical possibilities, while perhaps providing a better account of how we should conceive of wellbeing (and hence, if it is a matter of contributing to wellbeing, desirable mental states), aren’t relevant here; we are focused on our general social understanding of desirability.Footnote 26

I am not suggesting that our norms of desirability don’t compel us to (in typical cases) believe according to our evidence (or justification); if I lost five dollars, I shouldn’t simply disbelieve that I lost five dollars in order to be in a better mental state. Instead, I’m suggesting that our norms of desirability don’t require us to match apt or warranted emotions to those justified beliefs. [This is why some of the aforementioned philosophy of psychiatry literature on beliefs can’t simply be applied here; desirability interacts differently with justification (for beliefs) and warrant (for emotions).]

Consider two people who both have very mild depression, where one is properly responding to their circumstances (say, is working a minimum wage job, living in an unpleasant environment, doesn’t see any way to improve their circumstances), and the other has, by every measure we can think of except their depressive mental states, a meaningful, fulfilling, excellent, comfortable life (and where she can’t identify anything that her depression is even being responsive to), we don’t—and shouldn’t—judge it more desirable for the person working the minimum wage job to have mild depression simply because her depression is a warranted response to her circumstances. One might push back against this by pointing out that depression is a mental illness, and that warrant is only built into desirability insofar as we can maintain mental health while being in warranted states. This response falls apart, though, if—as I claim—a large part of how we determine what states count as together forming a mental illness is whether those states are desirable for us.Footnote 27

None of this should be taken to entail either of two ideas. The first is that, for reasons of justice, only Dominique is deserving of mental health care. The second, more interesting claim is that only Chip really has a mental disorder. (The depression case above suggests this might be true.) I am, in fact, sympathetic to the second claim as a bit of ideal theory (ignoring the important unwarranted symptoms Dominique has for a moment). In an ideal world, we might think: mental health care should be normalized and not intimately tied up with diagnoses. We all need mental health care when something goes wrong in our lives, but that’s not because we have a disorder. Thus it is Chip—who is improperly responding to his circumstances—who is diagnosable, but Dominique is no less deserving of mental health care for not being diagnosable. (Note that, if we do hold fixed that it must be responsive to objective trauma, this would define PTSD out of existence.) I don’t recommend this in our non-ideal world, because I believe it would exacerbate the very problems Meek Mill points out. (Think about the criminal justice system and the way it treats diagnoses as exculpatory, and then consider the consequences of treating Chip, but not Dominique, as diagnosable.)Footnote 28

To sum up so far: pro-warrant and pro-desirability psychosocial norms very often conflict—and they conflict systematically for people who have experienced serious trauma. We are too focused on pro-desirability norms and not focused enough on pro-warrant norms. And, given our ordinary social concepts of warrant and desirability, this can’t be reconciled by claiming that our pro-desirability norms actually have some kind of warrant requirement packed into them. Finally, maintaining pro-desirability norms but not pro-warrant norms helps to both obscure and reinforce structural oppression, in part because when things go wrong for agents, it focuses our attention only on their internal states, and not on the external causes of those states. I’ll unpack this through our test case in the next section.

6 Where is the injustice?

We might initially think that, insofar as there is a problem in Chip and Dominique’s case, it is some kind of epistemic or moral harm to Dominique as an individual.

Dominique is treated as exactly on a par with Chip from the perspective of her doctors and therapists. So, if she trusts her doctors and therapists as epistemic authorities, she should naturally conclude that either she and Chip both have warranted mental states, or neither of them do. (In fact, as Arpaly points out, Therapist probably just doesn’t care about this; perhaps if Therapist had managed to tell Dominique that he was solely focused on the desirability of people’s mental states, it would be somewhat easier to make this inference.) In Dominique’s case—and I suspect this is common—she takes the latter route, and ends up believing that her own mental states are not warranted. But, as I’ve argued, many of her mental states—and this includes at least some of her mental states which are treated as symptoms of PTSD—are warranted, and Therapist ends up undermining Dominique’s trust in herself as a sort of metaepistemic agent: as someone who can move a level up and evaluate whether she is appropriately responding to her evidence and circumstances.

If I am right that this is a common reaction, then what people end up epistemically sacrificing when they are diagnosed with and treated for PTSD is, in many cases, their own ability to idea to trust that their negatively-valenced mental states are warranted by the situation they are in.Footnote 29 Thus, this kind of false equivalence can lead to a kind of self-gaslighting by people like Dominique, which, in turn, can lead to broader failures of agents to recognize harms that are, at least in part, manifestations of systems of oppression.Footnote 30

This seriously wrongs Dominique as an epistemic agent: her trust in her own judgment about what kinds of directed emotional states are warranted and not warranted by her circumstances is undermined. Dominique suffers a kind of epistemic injustice, but one internal to her own agency: her judgments and emotions regarding her own trauma are undermined by (arguably) both testimonial and hermeneutical injustice, indirectly stemming from her psychiatric care, but directly stemming from a kind of higher-order double-bind: either she and Chip are both equally reasonable, or equally unreasonable; either option doesn’t fare well for her metaepistemic attitude towards her own mental states.Footnote 31

Imagine that we actually treated epistemologists as experts on rationality, and then imagine an expert epistemologist (who we might pay for weekly visits to help us be more rational agents) insistently telling you that there was no difference in the epistemic status between your beliefs, which are (stepping outside the scenario for a moment) actually justified, and the beliefs of someone with the very same evidence as you, who believes almost entirely oppositely to you. It is obvious that, if you really took this person to be an expert and yourself not to be, there would be bad results. Likely, either you would begin to believe that truth and justification were subjective and fully relative to the individual, or you would cease trusting your own mechanisms and attitudes about justification in your own case.

In Dominique’s case, this kind of personal injustice is, while serious, limited in scope. It negatively impacted Dominique’s trust in herself, and slowed down her recovery, but it’s not immediately clear how it connects to questions about structural injustice and oppression. And, I claim, our lack of attention to warrant is a social, not just a moral, problem, and both reinforces and is reinforced by our ideology of robust individualism. Thus I need to show that there is a broader social problem here. To do so, consider a different, much more public case. In 2015 Brock Turner raped Chanel Miller. In addition to having to deal with the trauma of being raped, Miller additionally suffered serious psychological harm from having her resultant trauma thought of, treated, and addressed as equivalent to (or, in many cases, less real or severe than) the “trauma” of her rapist who had to undergo a trial, go to jail for a few months, and miss some swim meets (see Miller, 2019).

I focus on Miller because, first, the very person who caused her trauma is the person she is being treated as on a par to, psychologically, by the general public, the courts, lawyers, etc. In Miller’s case, the psychological harm of having her trauma and her rapist’s “trauma” treated as equivalent—the equivalence enabled by our lack of attention to warrant—is thus much easier to be concerned by, than in the case of Chip and Dominique, who bear no relation to one another. Second, what was at stake in Miller’s case—rape and the kind of trauma and psychological damage it often inflicts on its victims—is thought by many of us to be a systematic injustice, a way that systematic oppression is reinforced and inflicted. And third, the case was squarely in the public eye.

This helps lead into motivating the general problem. The damage in Miller’s case was not just damage to Miller, though it is hard to underestimate the kind of psychological damage she was caused by the way she, and her rapist, were treated in both the public eye and the court system.

The broader social problem is that when we lose sight of the role that warrant plays in not just our beliefs but also our directed emotional states, we face inwards towards ourselves as damaged agents, and lose our ability to conceive of trauma-reactions as being generally warranted by structurally unjust or oppressive circumstances (we fail to look outwards to the world for the source of damage). Conceiving of our negatively-valenced emotional states as being properly reactive to what they are responses to is part of how we recognize, and can fight back against, oppression.Footnote 32

When we treat Turner’s negatively-valenced emotional states as on a par with Chanel Miller’s, we are treating the importance of getting people into positively-valenced emotional states as vastly more important than whether their negatively-valenced emotional states are warranted. (Thus further supporting my earlier claim that we focus too much on desirability at the expense of warrant.) But we need warranted directed emotional states to be able to see, expose, and be motivated to fight against injustice.Footnote 33

We also need constraints on when undesirable directed emotional states are taken as guides to actual problems we need to rectify in the world. Neither Chip nor Brock Turner are the victims of injustice. If their PTSD-like symptoms are directed towards their own experiences of trauma, then they are unwarranted, since they haven’t experienced trauma. If their emotional pain is interfering with their ability to function in the day to day, perhaps they need therapeutic or psychiatric intervention—I don’t deny that either is deserving of mental health care. (Though, if their mental health care fails to help them see themselves as perpetrators and not victims, perhaps we should deny this.) We must distinguish that, though, from the claim that their undesirable directed emotional states—if they are directed at themselves as victims—are guides to some actual wrong they have been the victim of. Warrant is what allows us to make that distinction. Importantly, this is not about—or at least not merely about—empathy. Empathy is a tool for understanding what it “feels like” to be the agent, but that means that it doesn’t help us get onto whether the agent is warranted in feeling that way, nor does warrant help us get onto empathy. Thus even an expanded version of Manne’s (2017) notion of ‘himpathy’ focused on a more general pattern of injustice and oppression doesn’t do similar work to the work that warrant does for us in distinguishing directed emotional states.

My first claim in this paper is that we must distinguish between warranted and unwarranted symptoms that help constitute mental disorders. We have now arrived at my version of King’s thesis, which is also my second claim: we need our “maladaptive” responses to certain situations in order to see that they are deeply awful and fight back against those situations. We need them in order to recognize that some circumstances warrant reactions that involve even such harms to us as agents as fragmentation of the self, as loss of control, and so on. We need our “maladaptive” trauma reactions too, even if they harm us. But—and this extends King’s claim further—just as my first claim has two sides (we must pay attention to lack of warrant, and not just warrant), so does this claim about systematic injustice. We also must pay attention to when maladaptive reactions are not a good guide to injustice. We need warrant when evaluating directed emotional states not just because warranted undesirable directed emotional states point at injustice, but also because unwarranted undesirable directed emotional states do not point at injustice, and must not be treated as doing so.

7 Paul on imposter syndrome

Sarah Paul (2019) argues that an ameliorative account of imposter syndrome must distinguish between belief states that are justified and unjustified; but typical discussion of imposter syndrome elides this distinction in favor of distinguishing between false or true beliefs. But focusing on justification allows us to give an analysis of when we need to change the social world vs. when we need to intervene (either on ourselves or others) to alleviate a problem that is internal to an agent. Paul points out that in academic environments, posturing and overconfidence are systematically rewarded (in white men—these are often punished in others), serving to justify our own beliefs in our own inadequacy even if those beliefs are actually false:

If one’s peers are accorded an inordinate amount of respect or credibility because of their confident presentation, or because they are members of a privileged class, this can help to justify the conclusion that you compare unfavourably. (2019, p. 240).

The solution to this problem, Paul argues, is not to intervene into the agent’s psychology to help her ‘fake it til she makes it’; it is to fix the credibility excess being awarded to her (typically more privileged in other ways as well) peers. The crucial point is that we can’t do so without distinguishing between ways in which one’s beliefs are justified by the (unjust) social circumstances in which they are formed, and ways in which they are not. In short, the problem is (often) that those with imposter syndrome are justified in feeling like imposters, because they are properly responding to the evidence that they have. It is the source of that evidence—the external social world—that we have to change, not their internal states.

As Paul points out, conceiving as ourselves as having imposter syndrome in the face of an unjust system of rewards and punishments in academe won’t help fix the core social problem, even if we “overcome” our imposter syndrome by “faking it til we make it”. Instead, focusing on ourselves will lead us to develop adaptive strategies to help ourselves stop feeling like imposters, and, perhaps, to get ourselves rewarded in similar ways to our more privileged peers.

Paul’s reasoning can be extended (a) from the connection between justification and beliefs to the connection between warrant and directed emotional states and (b) to clinical diagnoses (which are not special in some way; they are social constructs just like imposter syndrome is). Some of the symptoms of Imposter Syndrome, like some of the symptoms of PTSD, can be undesirable for us even when—or perhaps especially when—they are justified or warranted by what we know about the non-ideal social world and our place within it.

Conceiving of ourselves as having PTSD when we have warranted directed emotional states and beliefs towards our own trauma takes away our tools for fighting the cause of that trauma on the ground, because it takes our focus off the question “why did this happen to me” and onto being in “desirable” or “helpful” current mental states. Applied to PTSD, the real harm of our focus on desirability over warrant (in clinical, as well as social, contexts) is that it obscures the social-structural circumstances that lead to (at least partially warranted) PTSD. But it also obscures the difference between partially warranted and fully unwarranted cases of PTSD. And the latter reinforces the former: when cases that are unalike because one case is partially warranted and the other is not are treated alike, the message is that it is only what-is-happening-inside-of-us that needs fixing.

8 Intrinsic connections between warranted emotions and their objects

Clinical diagnoses like PTSD themselves can, on their own (given the way they are deployed) make it harder for us to see and fight against structural injustice. War is perhaps the best way to see this. PTSD is a clinical diagnosis because the set of symptoms associated with it are deeply harmful to those who have it as well as those around them. I don’t deny either that any of this is true, or that it is important to help individuals who have PTSD, to study what is happening in our brains and bodies when we exhibit symptoms of it, and so on (thus, I don’t deny that we should draw some boundaries around the symptoms of PTSD, in order to have an object of study). But we might imagine a world in which warranted responses to military trauma that form at least part of the cluster of PTSD symptoms are treated as in fact warranted rather than as a pathological problem with individuals. In such a world, these symptoms could serve partly as guides to what is wrong with war, rather than being pathologized and treated as defective or deviant from a warrant perspective.Footnote 34 This suggests that there is some connection between fitting or warranted negatively-valenced directed emotional responses and badness-in-the-world. Some of that badness-in-the-world is systematic injustice.

Consider our attitude to PTSD in veterans. Our current attitude is, I think, to take PTSD to be a bad consequence of going to war (for those who do develop PTSD). That is importantly different from taking PTSD to be a warranted reaction to going to war. We are almost exclusively focused on the damage PTSD does to one’s wellbeing and the wellbeing of one’s family and friends—it is that the symptoms of PTSD are “bad for” us that we think makes PTSD a bad consequence of going to war. And, because we care about it as a consequence of going to war, its very existence and manifestation may motivate some people to question the value of and justice in sending people to war.

But that military combat, or rape, or ongoing domestic abuse sometimes have as consequences PTSD doesn’t help us see what is intrinsically wrong with military combat, rape, or domestic violence in a systematic way. What we need to see that is warrant. In order for those of us who haven’t been deployed to or lived in a combat zone to be able to see just how bad that is, we need the claim that PTSD is not just a bad consequence of being deployed to a combat zone, but that it is the warranted response to both being a trained killer and witnessing the killing of one’s friends (and “enemies”). If we don’t focus on warrant, we do what we do now: try to treat PTSD to fix veterans’ directed emotional (and physiological) states—to fix the bad consequence—but not do anything to fix the externally-inflicted trauma—the horror of war.

Compare this to a toy case about smoking and cancer. Smoking tobacco is enjoyable, and puts most of us into a relaxed state, but not one that impairs our judgments or agency. Let’s imagine (contra the facts!) that smoking tobacco has its ordinary initial effect on our mood and mental state, but is only mildly physically addictive and doesn’t cause any immediate damage to our bodies or brains, those around us, or the environment. But hold fixed that smoking causes lung cancer in the long term. Now suppose that we found a 100% effective cancer vaccine, and everyone received it. I suspect many of us would go back to smoking, or stop trying to quit. Big Tobacco would lobby hard to relax restrictions, taxes, and so on. Our world would (smoking-wise) look a lot like it did before many of the harmful effects of smoking were made available to the public. And I doubt many of us would object: cancer is a mere bad consequence of smoking; there is no intrinsic moral connection between smoking and cancer; cancer doesn’t somehow reveal or guide us to the true nature of smoking (it’s not a “fitting” response to anything at all). So, it looks like, this is a place where we can simply engage in a bit of consequentialist reasoning that even staunch anti-consequentialists can accept.

But suppose we similarly found a way to prevent PTSD with a vaccine delivered in infancy. If we see PTSD as merely a harmful consequence of going to war—as a set of simply undesirable directed emotional and physiological states—we will celebrate having eliminated it, and continue to send people to war. If we instead see some of the symptoms of PTSD as a set of warranted and undesirable directed emotional states and beliefs—as the fitting response to the horrors of going to war—we should be concerned that a mass vaccination campaign is dystopian in a way that vaccination from cancer is not; that, just as if we developed a vaccine for smoking in my toy case, PTSD vaccination would be seen as removing moral and pragmatic stumbling blocks to large-scale military conflict. (If one isn’t on board with the idea that most military combat the US engages in is unjust, consider whether vaccination in infancy to prevent PTSD as a response to rape is a good idea.)

If we cared more about warrant, it might be those who didn’t develop PTSD in the face of long term military combat, or domestic abuse, or child abuse, or grew up in a community with very high levels of gang violence, who were pathologized. The “symptoms” of PTSD would be treated as reasonable—as warranted reactions to seemingly inescapable violence and trauma. And they would still be deeply harmful to both those who had them, and those around them. In other words, if we focused on warrant, we might be able to grasp the intrinsic connection between experiencing war and the warranted reaction to that experience.

A natural objection is this: we want people to have access to medication that helps them ease the symptoms of PTSD, and we shouldn’t judge people for taking medication. I agree with this, so let me clarify the purpose of the thought experiment. First, note that there’s a reason I was appealing to the idea of vaccination rather than treatment. The idea is that there is an important intrinsic connection between some of the symptoms of PTSD—the warranted ones—and experiencing combat warfare; those symptoms aren’t just bad consequences of going to war, they are instead part of what guides us to seeing the true horrors of war. I am not trying to lodge an objection against psychiatric medication. Instead I am trying to suggest that even those of us who think that, e.g., veterans or victims of rape or abuse should have access to—and should be able to opt for—psychiatric medication when they suffer PTSD in response to the horrors they have experienced, should be concerned that a vaccination campaign would be dystopian. The reason is that such a vaccination campaign would serve to socially disincentive us, over the long run, from comprehending the depth of the intrinsic wrongs of other-inflicted trauma by disabling us from having, witnessing, and recognizing trauma-reacting emotions in response to them. In other words, it would, I think, encourage the same kind of consequentialist reasoning as we saw in the smoking and cancer case, but in this case, that reasoning would serve to obscure a serious moral wrong.

Second, I want to again reinforce that this is not an anti-psychiatry paper. I am not against medication for PTSD, especially if it could target only those symptoms that are arguably either unwarranted in everyone (e.g.: if I am wrong about my earlier argument, flashbacks and intrusive memories), or not the sort of thing that is unwarranted or unwarranted (e.g.: perhaps hypervigilance or adrenaline regulation problems). What medications we take is in fact somewhat (but not entirely) irrelevant to my argument: we can imagine the very same drug helping Dominique and Chip, and nothing I’ve said entails that we should withhold it from either of them, nor even judge them for taking it. My claim is (strictly speaking, at least) orthogonal: we must take seriously the difference in epistemic status between their respective emotional and belief states, which is about their reasons, not (as choices about medication are) their management of those reasons.

Again, my focus on warrant should not be taken to imply a corresponding claim that some version of desirability is not central to our lives. In no sense do I think we ought not aim at desirability; just that we need to allow warrant to shape both how we respond emotionally to the world as individual agents, and how we understand structural injustice. I am not advocating for losing sight of desirability, and doing so would both cause and reinforce its own set of structural social injustices. Nor am I advocating for failing to treat those who are experiencing unwarranted sets of emotional, physical, and belief states. While my goal here is not to argue for a solution to the issues I’ve raised, I think that the way forward is not merely to attempt to better balance pro-desirability and pro-warrant norms, but also to try to reshape our psychosocial norms to focus more attention on the social world—and, in particular, on which of our mental states are properly reactive to the social world—and less attention on the agent-as-individual.

Notes

I don’t deny that we ought to treat PTSD as a mental disorder, nor that there are both normative and descriptive issues at stake in doing so. (Thus this might be construed as a “weak normativist”, not “strong normativist” (Szasz. 1961; Foucault, 1964) critique.) However, as we will see, my argument does point towards overhaul at both the conceptual (we must conceive of it as a disorder grounded in the world/environment) and diagnostic (we must distinguish between similar symptoms that are agentially vs. environmentally grounded) levels.

See also Scrutton (2015a).

There are important differences between warranted emotions and beliefs (e.g. warrant of directed emotional states is (on my view) not unique, e.g., two people can appropriately grieve the death of a friend with distinct sets of emotional reactions, whereas I am neutral about uniqueness for justification).

I don’t claim that what is warranted is fixed, or fully fixed, by mind-and-language-independent facts. Indeed, I believe that our social practices and ideology contribute to not just the strength of our norms about warrant and desirability, but also their shape.

D’Arms and Jacobson (2000) distinguish between what is fitting to feel and what is right or wrong to feel (granting, e.g., that Taylor (1975) might be correct that anger is always wrong (morally) to feel, if it is wrong to feel so “concerned with what is due to one” (Taylor, 1975, 402), but that the further claim that anger is never warranted is wrong). I agree that warrant has little (directly) to do with what is morally right, just as what we should believe on the basis of our evidence has little to do with what is morally right, but if one takes the belief-emotion analogy seriously here, this issue is about whether an analogue of moral encroachment is true for warrant.

I don’t mean to be ruling out that we construct these facts somehow—but they are not individually subjective.

See e.g. Kendell and Jablensky (2003), Andreasen (2007), who point to an intentional decision in the construction of the DSM to focus on reliability over validity. Also see Frances and Widiger (2012), Scrutton (2015b). Scrutton claims that folk-psychiatry concepts tend to be more essentialist, whereas professional-psychiatry concepts tend to be more pragmatic (15). Murphy (2005) critiques the DSM for using something like folk-theoretic, “common sense” ideas about the mental rather than being more scientific, and advocates a focus on causal mechanism. Tabb (2015) sharpens the issue by pointing out that it is actually the assumption that “operationalized criteria for diagnosing clinical types will also successfully pick out populations about which relevant biomedical facts can be discovered” (2015, 1048) that is the real issue here.

Frances and Widiger (2012), make claims about the epistemology and method of the DSM that seem to support Pickard’s claim.

In particularly oppressive contexts, things are more complicated: warrant and desirability norms both systematically conflict, and are systematically enforced, thus putting the oppressed in a double bind. Fully elaborating this is a project for a different paper. (See Srinivasan, 2018 for related argument, and Hirji, 2021 for an account of double binds that fits with this claim.).

See Haslam (2016).

This is, of course, contentious: our inductive learning should arguably rationally be better adaptive to shifts in circumstances. But given that, e.g., victims of abuse are likely to be re-abused, it’s at least unclear exactly what the new circumstance warrants.

Meek Mill’s comments apply here as everywhere—if Mare were not a middle class white woman she would be treated quite differently.

For a critique of the view that, e.g., emotions like grief are “healing processes”, see Marušić 2022, 3.4.

Marušić is partly drawing on Moller (2007), who motivates a similar tension in discussing “resilient” grief.

I focus on Marušić’s discussion of grief because it most closely connects to my argument here, but it’s important to note that there is much disagreement both about what grief is and what role it plays in our lives. (And I don’t intend to be appealing to authority here.) See, among others, e.g. Cholbi (2022), Garland (2021, ch. 5) for grief’s connection to the shaping of identity/self; Atkins (2022) for the relationship between grief and intimacy with the self; Ratcliffe, Richardson, and Millar (2022) on a distinct account of grief’s object; Olberding (2007) on grief in the Zhuangzi/the importance of the capacity for sorrow; Gustafson (1989) on grief as a combination of belief (in the loss) and unsatisfiable desire (that it not be the case); and Price (2010) on grief involving two distinct forms of sadness.

Again, this isn’t an anti-therapeutic or anti-psychiatric treatment paper; the harm that PTSD causes to the agent and those around her are real and serious.

James Fritz (2021) makes a similar point about anxiety: because anxiety is overwhelmingly both fitting and imprudent, “for almost any actual person, it’s impossible to have an overall emotional state that meets the standards of both fitting emotion and prudent emotion.” Michael Cholbi (2017) makes a similar point about grief, and Marušić presents a similar puzzle about grief (2018, 2022) and our response to injustice (2020). Srinivasan (2018) points to a more systematic tension for the oppressed.

Such accounts of wellbeing are relevant to the broader project, if we are looking to ameliorate by conceptually engineering—one way to rectify the way in which desirability trumps warrant norms is by shifting our concept of desirability to one of warrant-including well-being. (This is not my favored solution).

Ruth Whippman (2017) gives an account of the United States’ “happiness industrial complex” and the positive psychology movement, which explains why happiness (and, in particular, happiness that we achieve precisely by being in unwarranted positive mental states—by making peace with any problematic circumstances we are in) is so central to our shared social concept of desirability. Horwitz and Wakefield (2007) provide an extended account of the ways in which fitting/warranted sadness (and other negative emotions) are treated as clinical depression, and the problems this presents.

Instead, insofar as this paper contains a concrete recommendation for mental healthcare providers (which is not my primary goal), it is primarily at the therapeutic level: recognize and mark the distinction between warranted and unwarranted emotions. Perhaps an intermediary suggestion can also be made: distinguish diagnostically between (partly) warranted PTSD and unwarranted PTSD.

Arpaly, who makes similar comments, also points out that this kind of thing can be taken to undermine the way in which we take our own lives and projects to be meaningful (for example, if the artist is told that his “state of inspiration is actually… hypomania, and that hypomania is a symptom of a disease” he may be “insulted or devastated” (2005, 290), though she argues that it is a mistake for us to respond this way.

Abramson (2014) gives an account of gaslighting that is useful here, though it is unclear whether Therapist is guilty of gaslighting—something more complex is happening here. (Therapist is in the grip of a theory on which his speech is both true and helpful.) Dandelet (2021) gives a more extensive account of self-gaslighting.