Abstract

Background Inappropriate use of antibiotics is a public health problem of great concern. Objective To evaluate knowledge of antibiotics, race, gender and age as independent risk factors for self-medication. Setting Residents and population from different regions of Saudi Arabia. Methods We conducted a cross sectional survey study among residents. Data were collected between June 2014 to May, 2015 from 1310 participants and data were recorded anonymously. The questionnaire was randomly distributed by interview of participants and included sociodemographic characteristics, antibiotics knowledge, attitudes and behavior with respect to antibiotics usage. Main outcome measure Population aggregate scores on questions and data were analyzed using univariate logistic regression to evaluate the influence of variables on self-prescription of antibiotics. Results The response rate was 87.7 %. A cumulative 63.6 % of participants reported to have purchased antibiotics without a prescription from pharmacies; 71.1 % reported that they did not finish the antibiotic course as they felt better. The availability of antibiotics without prescription was found to be positively associated with self-medication (OR 0.238, 95 % CI 0.17–0.33). Of those who used prescribed or non-prescribed antibiotics, 44.7 % reported that they kept left-over antibiotics from the incomplete course of treatment for future need. Interestingly, 62 % of respondents who used drugs without prescription agreed with the statement that antibiotics should be access-controlled prescribed by a physician. We also found significant association between storage, knowledge/attitudes and education. Conclusions The overall level of awareness on antibiotics use among residents in Saudi Arabia is low. This mandates public health awareness intervention programs to be implemented on the use of antibiotics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impacts on practice

-

Residents in Saudi Arabia show low level of awareness on the use of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance.

-

There is an urgent need for public health intervention programs to increase the awareness on use and knowledge towards antimicrobial resistance in Saudi Arabia.

-

It must be possible to implement strict legislatures on the dispensing of antibiotics without prescription in Saudi Arabia because Saudi patients who used an antibiotic without prescription agreed with the statement that antibiotics should be access-controlled drugs prescribed by a physician.

Introduction

Antibiotics have been potential sources of life-saving and protection against infectious diseases, but they are hampered by the propensity of bacteria to rapidly develop resistance, which often results in failure of therapy. Antimicrobial resistance represents a current and ongoing threat to human and animals [1, 2]. Both appropriate and inappropriate antibiotic use drive antimicrobial resistance [3, 4]. Inappropriate use of antimicrobial agents and the consequences of spread of antimicrobial resistance is an ever existing public health problem of great concern. In recent years, resistance to antimicrobial agents that were previously effective has emerged or re-emerged in many geographical regions causing global health threat and huge economic impacts that involve humans, livestock, and wildlife. In the United States, it is estimated that two million people become infected with antimicrobial resistant pathogens, and there are twenty thousand antimicrobial resistant related deaths annually [5].

Antimicrobial resistance is a global public health concern. Antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest threats to human health nowadays. In the latest available Saudi census [6], Saudi nationals comprised around 68.9 % of the total population (27.1 million) and the expatriate (non-Saudi) population accounted for 31.1 % of the total population of Saudi Arabia. The non-Saudi population has distinct racial, socioeconomic, and demographic characteristics; accordingly, the received healthcare, response to therapy, and clinical outcomes may differ in this population compared to the population of Saudi nationals. Furthermore, Saudi Arabia is a multi-population country involving a unique and dynamic influx of expatriate workers from numerous countries, and tourists all over the year [7, 8]. Non-prescription dispensing of antibiotics remains a public health issue in Saudi Arabian community raising an increasing concern on its contribution to the spread of antimicrobial resistant pathogens and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance [9–12].

More importantly, the country is the focus of pilgrimage for Muslims from all over the globe for the hajj practice where more than a million of pilgrims gather annually for at least one-month stay in Mecca. In addition, pilgrims visit Mecca all year round for practicing Umrah and some of them can stay up to 3 months in Mecca and may visit other key religious cities and sites. Altogether, this creates a critical public health issue due to extreme congestion of people and may facilitate the occurrence and global spread of several infectious diseases of bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections specifically if the existing infection control and healthcare systems are not well-prepared or experienced [7, 13]. These factors may drive a need to use antibiotics, often inappropriately. The only existing public health contingency plan for hajj focuses on vaccination against infectious diseases. The ongoing uncontrolled use of antibiotics together with the traffic of people through Saudi Arabia during these circumstances have the potential to contribute to national as well as global spread of resistant infectious agents.

Access to antibiotics is uncontrolled among the Saudi population and it is not prescription restricted. Antibiotic agents are available and accessible to the public and can be bought over the counter. There may be silent unreported outbreaks in Saudi hospitals and in healthcare settings. There is no national surveillance system on antimicrobial resistance and healthcare acquired infections. This free access to antibiotics changes the context for antibiotic related interventions in Saudi Arabia. Data on the awareness, among patients and the public, about antibiotic resistance revealed that antimicrobial resistance is an escalating serious concern [10]. There are few reports in literature on the use of antibiotics among the population in Saudi Arabia.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge and behaviours of Saudi individuals towards antibiotics use and self-medication.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The research protocol of the present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Future Scientists Program Committee and faculty of Public Health, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Study population

A cross sectional epidemiological study using survey design was carried out from June 2014 to May, 2015. The inclusion criteria were that participants had to be Saudi nationals and legal resident non-Saudi nationals. All participants had to be older than 18 years and had to have volunteered to participate in the survey. All participants were asked to give a written consent. To avoid double-counting of participants, each participant provided a unique national identification number. The identity of participants was anonymized through the process of data analysis.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed according to scientific literature and the antimicrobial resistance report by the World Health Organization [14, 15] and the questionnaire was presented in written form in Arabic or English by the team. The completed questionnaires were then analyzed. The questionnaire included socio-demographic characteristics, antibiotics knowledge, attitudes and behavior as predictors for antibiotics usage. The questionnaire was conducted among the public in Southwestern region of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as well as randomly selected participants from other regions of the kingdom. The questionnaire was distributed by random in person interview of participants in public areas, clinics, hospitals, houses, and universities.

Analysis

Data were recorded anonymously in a Microsoft excel database and transferred to PASW statistical software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA, version 18.0), which was used for all analyses. The dependent variable, self-prescription of a respondent, was defined as prescription by anyone else than a physician (including pharmacists, nurses, friends, etc.). Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the influence of independent variables on self-prescription of antibiotics. The regression outcome of self-prescription was given by the estimated odds ratios and the corresponding 95 % confidence intervals. Hypothesis tests for regression coefficients (Wald-tests) were performed and expressed with p values at the significance level α = 0.05. Knowledge was measured using a scoring system. There were four questions on basic knowledge, namely (1) What is an antibiotic? (2) What is a prescription? (3) Can antibiotics be used for all types of infections including viral, bacterial, and fungal origin? (4) Are antibiotics used to treat viral infections? Three other questions were more specialized, namely (1) Do you know what antimicrobial susceptibility testing is? (2) Have you heard of the term antimicrobial resistance before? (3) Do you know what antimicrobial resistance is? The variable total knowledge was computed in a way to reflect the different degrees of difficulty for the individual questions. For the four basic questions, the wrong answer resulted in a score of 0, the right answer in a score of 1, and answer “do not know” in a score of 1/3. Responses in the three specialized questions resulted in a score of 1 for the answer “yes”, and a score of 0 for the answer “no”. The value of the final variable total knowledge was defined as the sum of the scores of all seven knowledge questions. This gave a Cronbach α—value of 0.537. The association of demographic characteristics with a number of chosen variables was investigated using Pearson’s Chi square tests.

Results

Of the 1310 questionnaires that were distributed, 161 were returned as uncompleted and 1149 were returned as completed. The response rate was 87.7 %. The socio- demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Among respondents, 41 % were males, and most of respondents were educated except for 6.6 % were illiterate, and respondents represented different residents from different regions in Saudi Arabia shown in Fig. 1. The mean age of participants was 26.8 (SD 8.8). The majority of respondents were female (59.0 %) and Saudi nationals (90.7 %).

Study site locations in Saudi Arabia. Residents from different provinces including Makkah Al Mokaramah, Al Madinah Al Munawarah, Jeddah, Taif, Riyadh, Al Baha, Jazan, Bisha, Najran, Abha, Tabuk, Sakaka, Hail, Buraydah, Al Hofuf, and Dammam were included in the study. Non Saudi residents included nationals from Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Sudan, Syria, United Arab Emirates and Yemen. Figure was reproduced from World fact book available at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/docs/refmaps.html

Further, 71 % of the respondents reported that they had used an antibiotic in the last 6 months. About 63.6 % of participants reported that they had purchased antibiotics without a prescription from pharmacies; 71.1 % reported they did not finish the antibiotic course as they felt better. Of those who used prescribed or non-prescribed antibiotics, 44.7 % reported that they kept left-over antibiotics from the incomplete course of treatment for future need.

Interestingly, 62 % of respondents who used antibiotics without prescription agreed with the statement that antibiotics should be access-controlled drugs prescribed by a physician.

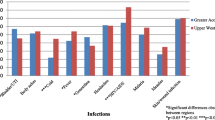

Amoxicillin and its combination with clavulanate was the most commonly requested antibiotic and was dispensed in 29.2 % of cases. We found that 18.2 % of participants self-medicated with antibiotics for respiratory diseases (Fig. 1).

Logistic regression analysis examining the predictors of self-medication with antibiotics was conducted and presented in Table 2. We identified that female respondents were less likely to self-medicate with antibiotics than males (OR 0.635, 95 % CI 0.49–0.82) and Saudi nationals were less likely to self-medicate with antibiotics than representatives of other nationalities (OR 1.8, 95 % CI 1.2–2.69). The association between self-medication and gender was not confirmed by a confounding effect of education, despite the fact that women were less educated than men. The availability of antibiotics without prescription was positively associated with self-prescription (OR 0.238, 95 % CI 0.17–0.33). In addition, using a non-professional source of health-related information about antimicrobial resistance (like internet) was positively associated with taking antibiotics without prescription (OR 1.575, 95 % CI 1.2–2.07).

The following independent variables were also positively associated with self-medication: taking antibiotics following pharmacist’s advice without physician referral (OR 0.241, 95 % CI 0.16–0.35), keeping left-overs (OR 0.412, 95 % CI 0.31–0.55), and incomplete course of antibiotic treatment (OR 1.932, 95 % CI 1.42–2.64). The following predictors were negatively associated with self-medication: using for the treatment of acute upper respiratory infections (OR 0.242, 95 % CI 0.125–0.469), and total knowledge (OR 0.917, 95 % CI 0.85–0.99).

The results of the relationship between individual’s socio-demographic characteristics and storage of antibiotics, attitudes toward and knowledge of the antibiotic use were shown in Table 3.

Nationality had no significant effect on each of the statements as most of respondents were Saudis. There was no association found with marital status. Gender, age and education were significantly associated with knowledge of antimicrobial resistance. We also found significant interactions between storage, knowledge/attitudes and education.

Figure 2 shows the frequency of diseases which antibiotics were used for by the respondents. In addition, 1.04 % of female respondents in the present study reported to self-medicate with antibiotics when they experience menstrual cycle and its associated symptoms such as headache, colic and vaginal pain.

Discussion

There are many drivers for the emergence of antimicrobial resistance among pathogens. Inappropriate use of antibiotics constitutes a growing global public health concern. Increasingly, there are reports of outbreaks caused by bacterial strains that have acquired multiple mechanisms of antimicrobial drug resistance [16, 17]. The unnecessary widespread and imprudent use of antibiotics in humans and in agriculture plays an inevitable role in the increasing problem of antimicrobial resistance in both developing and developed countries [18, 19]. In the present study, a high participation rate of 87.7 % is a major strength. The present study found significant interactions between storage, knowledge/attitudes and education. A significant finding of the present study is that the overall level of awareness on the use of antibiotics and education on antibiotic resistance among residents in Saudi Arabia were found to be low. The study targeted populations including Saudi nationals as well as non-Saudi residents who come from various parts of the world. The overwhelming respondents of Saudi nationals were an objective to mainly target Saudi nationals and it is related to the cultural effects as a risk factor for the non-prescription and increased use of antibiotics.

It was found that 63.6 % of participants reported to have purchased antibiotics from pharmacies without a prescription from the physician. This may be explained by the fact that although many policies exist to regulate antibiotic use but enforcement, education on antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance are insufficient or lacking. Results of the present study are alarming and we hypothesized that if access to antibiotics among Saudi population is controlled, it should reduce the irrational use of antibiotics and consequently will contribute to the reduction of the associated antimicrobial resistance threat.

In the present study use of internet as a nonprofessional indiscriminate drug use and source for prescription of antibiotics was positively associated with taking antibiotics without prescription (OR 1.575, 95 % CI 1.2–2.07) similar to other studies where it was reported that internet is a source of medicines and antibiotic abuses [20, 21]. In the present study, it was found that the majority of respondents were female (59.0 %) which could be attributed to that females are more likely to self-medicate with antibiotics because they might use these antibiotics to treat respiratory tract symptoms among their children as shown Fig. 2. Self-medication contributed to the excessive use of antibiotics as was previously reported [22, 23].

The findings of the present study demonstrate the community antibiotic medications overuse, which may contribute to increase antibiotic resistance. It has been previously reported that antibiotic overuse contribute to the increased antimicrobial resistance as well as emergence of resistant bacterial strains [24]. Consequently, the findings of the present study suggest that the community antibiotic medications overuse may contribute to increase antibiotic resistance in Saudi Arabia and the spread of multidrug resistant bacteria.

Our results are similar to another study performed in Saudi Arabia [15] which confirmed that 48 % of participants reported using antibiotics without consulting a physician. In addition, reports from neighboring countries including Iraq, Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, as well as other parts of the globe showed the imprudent, overuse and self-medication with antibiotics [23, 25–31].

Conclusion

The findings of the present study clearly highlight the need for better implementation of antibiotic stewardship, legislation of antibiotic use and a need for surveillance programs on antimicrobial prescription and resistance in hospitals and primary care settings in Saudi Arabia. Future effective enforcement of legislations regarding antibiotic access in community in Saudi Arabia should be advocated and will help change the driving factors for purchasers.

In addition, optimizing antibiotic use should also be achieved by changing patient and clinician behaviors in the community and hospitals. We have found unrestricted overuse of other classes of medications that require further attention including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and antiviral agents among participants. More importantly, outpatient prescription practices in health centers, primary care settings, and hospitals require investigation to guard against the overuse of antibiotic medications among population in Saudi Arabia. Among the proposed methods that will help track antibiotic prescription in communities is an antibiotic prescription data records and network to monitor all dispensed antibiotics in pharmacies and hospitals. In conclusion, results of the present study recommend that public health awareness intervention programs on the use of antibiotics should be implemented. In addition, health care decision makers should implement policies on access, use and prescription of antibiotics and to further limit and control the access to antibiotics. This will eventually reduce the increasing level of resistance and will help alleviate the ever increasing antimicrobial resistance crisis.

References

Huttner A, Harbarth S, Carlet J, Cosgrove S, Goossens H, Holmes A. Antimicrobial resistance: a global view from the 2013 world healthcare-associated infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2013;2:31.

El Zowalaty ME, Al Thani AA, Webster TJ, El Zowalaty AE, Schweizer HP, Nasrallah GK, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: arsenal of resistance mechanisms, decades of changing resistance profiles, and future antimicrobial therapies. Future Microbiol. 2015;10(10):1683–706.

Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M, Group EP. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365(9459):579–87.

Spencer J, Milburn E, Chukwuma U. Correlation between antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli infections in hospitalized patients and rates of inpatient prescriptions for selected antimicrobial agents, department of defense hospitals, 2010–2014. MSMR. 2016;23(3):6–10.

Antibiotic Resistance Threats—Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Cited 22 April, 2015. www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf.

Statistical Year book. Saudi Arabia Central Department of Statistics and Information database (Riyadh). http://www.cdsi.gov.sa/yb49/ http://www.cdsi.gov.sa/yb49/. Accessed 21 April 2015.

Memish ZA, Venkatesh S, Ahmed QA. Travel epidemiology: the Saudi perspective. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21(2):96–101.

Steffen R, Baños A. Travel epidemiology—a global perspective. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21(2):89–95.

Bawazir S. Prescribing pattern at community pharmacies in Saudi Arabia. Int Pharm J. 1992; 6(5).

Emeka PM, Al-Omar M, Khan TM. Public attitude and justification to purchase antibiotics in the Eastern region Al Ahsa of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2014;22(6):550–4.

Emeka PM, Al-Omar MJ, Khan TM. A qualitative study exploring role of community pharmacy in the irrational use and purchase of nonprescription antibiotics in Al Ahsa. Eur J Gen Med. 2012;9(4):230–4.

Khan TM, Ibrahim Y. A qualitative exploration of the non-prescription sale of drugs and incidence of adverse events in community pharmacy settings in the Eastern Province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract. 2013;20(1):26–31.

Ahmed QA, Arabi YM, Memish ZA. Health risks at the Hajj. Lancet. 2006;367(9515):1008–15.

Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/.

Belkina T, Al Warafi A, Eltom EH, Tadjieva N, Kubena A, Vlcek J. Antibiotic use and knowledge in the community of Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Uzbekistan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8(04):424–9.

Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. World Health Organization; 2014.

Levy SB, Marshall B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat Med. 2004;10:S122–9.

Wise R, Hart T, Cars O, Streulens M, Helmuth R, Huovinen P, et al. Antimicrobial resistance: is a major threat to public health. BMJ. 1998;317(7159):609.

Roca I, Akova M, Baquero F, Carlet J, Cavaleri M, Coenen S, et al. The global threat of antimicrobial resistance: science for intervention. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;6:22–9.

Currie J, Lin W, Zhang W. Patient knowledge and antibiotic abuse: evidence from an audit study in China. J Health Econ. 2011;30(5):933–49.

Forman RF, Marlowe DB, McLellan AT. The internet as a source of drugs of abuse. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(5):377–82.

Raz R, Edelstein H, Grigoryan L, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Self-medication with antibiotics by a population in northern Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7(11):722.

Al-Azzam S, Al-Husein B, Alzoubi F, Masadeh M. Self-medication with antibiotics in Jordanian population. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2007;20(4):373–80.

Nguyen KV, Do NTT, Chandna A, Nguyen TV, Pham CV, Doan PM, et al. Antibiotic use and resistance in emerging economies: a situation analysis for Viet Nam. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1158.

Dooling KL, Kandeel A, Hicks LA, El-Shoubary W, Fawzi K, Kandeel Y, et al. Understanding antibiotic use in Minya District, Egypt: physician and pharmacist prescribing and the factors influencing their practices. Antibiotics. 2014;3(2):233–43.

Al-Ramahi R. Patterns and attitudes of self-medication practices and possible role of community pharmacists in Palestine. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51(7):562–7.

de Melo MN, Madureira B, Ferreira APN, Mendes Z, da Costa Miranda A, Martins AP. Prevalence of self-medication in rural areas of Portugal. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28(1):19–25.

Jassim A-M. In-home drug storage and self-medication with antimicrobial drugs in Basrah, Iraq. Oman Med J. 2010;25(2):1–9.

Muras M, Krajewski J, Nocun M, Godycki-Cwirko M. A survey of patient behaviours and beliefs regarding antibiotic self-medication for respiratory tract infections in Poland. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9(5):854–7.

Shet A, Sundaresan S, Forsberg BC. Pharmacy-based dispensing of antimicrobial agents without prescription in India: appropriateness and cost burden in the private sector. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4(1):1.

Ramay BM, Lambour P, Cerón A. Comparing antibiotic self-medication in two socio-economic groups in Guatemala City: a descriptive cross-sectional study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;16(1):11.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to participants for providing their time and information. Authors would like to thank Deanship for Scientific Research, Jazan University, KSA. The present project was conducted and supervised by Prof. Dr Mohamed Ezzat El Zowalaty as part of the JU Future Scientists program's II projects. This project was supported in parts by the Grant of Charles University in Prague (SVV 260,187) for statistical analysis. The sponsors of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study. MEZ conceived and designed the study; SD, MAG, FAM, NIN, RK, RS, KD, MK, SH, BM, AG, RH, JZ, AWA, AAA performed the experiments; MEZ, TB, JDT analyzed the data; JV contributed analysis tools; MEZ and AEZ statistics analysis, MEZ wrote the paper, MEZ and TB revised it at all stages of publication, HAA, SB, AK, TB, AN, AEZ, MEZ revised the manuscript.

Funding

The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Prof Dr Mohamed Ezzat El Zowalaty is listed as a member and champion of "Antibiotic Action" an independent UK-led global initiative wholly funded by the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

El Zowalaty, M.E., Belkina, T., Bahashwan, S.A. et al. Knowledge, awareness, and attitudes toward antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance among Saudi population. Int J Clin Pharm 38, 1261–1268 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0362-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0362-x