Abstract

This paper investigates when and how children figure out the force of modals: that possibility modals (e.g., can/might) express possibility, and necessity modals (e.g., must/have to) express necessity. Modals raise a classic subset problem: given that necessity entails possibility, what prevents learners from hypothesizing possibility meanings for necessity modals? Three solutions to such subset problems can be found in the literature: the first is for learners to rely on downward-entailing (DE) environments (Gualmini and Schwarz in J. Semant. 26(2):185–215, 2009); the second is a bias for strong (here, necessity) meanings; the third is for learners to rely on pragmatic cues stemming from the conversational context (Dieuleveut et al. in Proceedings of the 2019 Amsterdam colloqnium, pp. 111–122, 2019a; Rasin and Aravind in Nat. Lang. Semant. 29:339–375, 2020). This paper assesses the viability of each of these solutions by examining the modals used in speech to and by 2-year-old children, through a combination of corpus studies and experiments testing the guessability of modal force based on their context of use. Our results suggest that, given the way modals are used in speech to children, the first solution is not viable and the second is unnecessary. Instead, we argue that the conversational context in which modals occur is highly informative as to their force and sufficient, in principle, to sidestep the subset problem. Our child results further suggest an early mastery of possibility—but not necessity—modals and show no evidence for a necessity bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Modals are used to talk about possibilities and necessities, that is, non-actual states of affairs. This paper investigates how children figure out the force of the modals in their language: that words like can, may, or might in (1a) express possibility, whereas words like must, should, or have to in (1b) express necessity.

-

(1)

The experimental literature on children’s modal comprehension suggests that they struggle with modal force until at least age 4: they tend to both accept possibility modals in necessity situations and necessity modals in possibility situations (e.g., Noveck 2001; Ozturk and Papafragou 2015). Typically, these errors are attributed to reasoning difficulties: children over-accept possibility modals in necessity situations because of difficulties reasoning about when a stronger modal would be more appropriate (i.e., they have trouble with scalar implicatures); they accept necessity modals in possibility situations because of difficulties reasoning about open possibilities (Acredolo and Horobin 1987). Usually, these studies take for granted that children already know the underlying force of modals. However, children’s difficulties could reflect a lack of knowledge of their underlying force. In this paper, we address more directly the questions of when and how children figure out modal force by investigating modal talk to and by young children with a corpus study of the Manchester Corpus of UK English (CHILDES database, MacWhinney 2000; Theakston et al. 2001) and four experiments based on a modified version of the Human Simulation Paradigm (HSP; Gillette et al. 1999), testing how well adult participants can guess the force of modals uttered by either children or their mothers from the conversational context alone.

Imagine a child who hears a new modal, sig: ‘You sig go this way.’ How can she determine whether sig expresses necessity or possibility? The modal’s syntactic position, before a verbal complement, might help narrow candidate meanings to expressing some kind of modal meaning (in the spirit of Landau and Gleitman’s 1985 syntactic bootstrapping hypothesis), but it cannot help distinguish force, since possibility and necessity modals can appear in all the same syntactic environments. Cues from the physical context are also bound to be limited, since modals express non-actual concepts, with few physical correlates (Landau and Gleitman 1985). To learn the force of modals, children might thus need to rely heavily on cues from the conversational context. But how informative is the context about modal force?

One issue that might make this mapping of modal form to force particularly challenging is that necessity entails possibility: If you must go this way, considering the range of passable routes, then you can go this way, given that same set of options. Likewise, if you must eat with your right hand, given the rules of etiquette, then those same rules imply you can eat with your right hand. So, if you think that sig means ‘possible’ but in fact it means ‘necessary’, it is unclear how you can discover that in fact, sig has a stronger meaning: in situations where a necessity modal is used, a possibility statement is also systematically true. What then prevents learners from postulating possibility meanings for necessity modals like must or have to? This kind of subset or entailment problem arises whenever two words’ meanings enter into a set/subset relationship, and has been discussed for content words, like dog/animal (e.g., Xu and Tenenbaum 2007), and quantifiers, like some/every and numerals (e.g., Piantadosi 2011; Piantadosi et al. 2012a; Rasin and Aravind 2020). In this paper, we focus on this issue for modals.

Different types of solutions have been proposed in the literature for how learners resolve or sidestep subset problems.Footnote 1 The first one is for them to rely on downward-entailing (DE) environments, which reverse patterns of entailment, as Gualmini and Schwarz (2009) suggest as a general solution to subset problems. The second is a bias toward strong (here, necessity) meanings, in the spirit of Berwick (1985). The third one is for the conversational context in which modals occur to be rich enough for learners to infer their force, without having to rely on either DE environments or a necessity bias (Dieuleveut et al. 2019a; Rasin and Aravind 2020 for every).

According to the first solution, all that children need to solve the subset problem is to observe necessity modals in DE environments, for instance under negation, as these environments reverse patterns of entailment (not possible entails not necessary). If children hear ‘You don’t have to go this way’ in a situation where it is clear that there are other ways to go, they should be able to infer that have to doesn’t express possibility: if it did, its negation would mean impossible, and wouldn’t allow for other ways. We argue that this is not a viable solution for modals. First, our corpus results show that necessity modals rarely occur with negation, let alone in other DE environments, in the actual input to children. Second, problems arise from the fact that scope relation between modals and negation are idiosyncratic. Necessity modals do not uniformly scope under negation: have to does, but must and should do not (Iatridou and Zeijlstra 2013). Third, instances where necessity modals do occur with negation are the least informative about their force: our experimental results show that participants had the most difficulty guessing the force of necessity modals in negative contexts.

If learners cannot clearly rely on DE environments, they may need a bias toward necessity meanings. According to this second solution, children would assume necessity meanings by default and revise their hypothesis only for possibility modals, when hearing them used in situations of non-necessity. This kind of solution, proposed for other instances of the subset problem,Footnote 2 has been criticized by many authors, both on conceptual (Gualmini and Schwarz 2009) and empirical grounds (Musolino 2006; Piantadosi 2011; Piantadosi et al. 2012a; Rasin and Aravind 2020; Xu and Tenenbaum 2007; for a summary, see Musolino et al. 2019). But such a bias could be necessary in the case of modals: there may, for instance, be fewer visual cues about their meanings than for concrete objects or even quantifier meanings, since they express abstract concepts about the non-actual.

In this paper, we argue that a necessity bias may not be necessary, even in the case of modals, and that the subset problem is in principle solvable based solely on cues stemming from the conversational context in which modals occur (Dieuleveut et al. 2019a). Rasin and Aravind (2020) reach a similar conclusion for every: while truth-conditional evidence alone may not allow the child to block an existential meaning (e.g., some) for every, pragmatic evidence can play an important role in sidestepping it. Rasin and Aravind consider potential sources of truth-conditional evidence against an existential meaning: DE environments, non-monotonic environments, and environments where the existential quantifier cannot be used (NPI-licensing, almost, nearly, and exceptive but). They show that such cases are very rare in the input (1.75% of every utterances), but that informative pragmatic evidence for rejecting an existential meaning for every is systematically available. Indeed, often enough (17%) when every is used in questions or assertions, its existential counterpart is already part of the common ground (as determined by the two authors). Hence, if every had an existential meaning, its use would result in a trivial contribution (e.g., asking “is someone here?” or asserting “someone is here” in a context where someone has arrived). They conclude that if children assume that speakers do not make vacuous contributions, they could infer that every does not have an existential meaning and thus sidestep the subset problem without special learning principles.

In this study, we probe the role of context in a different way, by having naïve speakers guess the force of modals based on the context of use, expanding on Dieuleveut et al. (2019a).Footnote 3 Our experimental results show that this conversational context is informative about modal force: for the most part, participants were able to accurately recover the force of both possibility and necessity modals from mere snippets of conversation. Thus, in principle, learners should be able to figure out modal force based on cues from the conversational context alone and solve the subset problem without having to rely on DE contexts or on a necessity bias. But while a necessity bias is in principle not necessary on the basis of the input, children may still make use of one in practice. However, we find no evidence for a necessity bias in young children’s modal productions.

Our current understanding of young children’s modal force use is limited. Comprehension studies (e.g., Hirst and Weil 1982; Byrnes and Duff 1989; Noveck 2001; Ozturk and Papafragou 2015, a.o.) tend to focus on older children. Corpus studies (e.g., Kuczaj and Maratsos 1975; Papafragou 1998; Cournane 2015, 2021; van Dooren et al. 2017) tend to focus on modal flavor, and while they note when particular lexemes first appear in children’s productions, to date no study systematically examines modal force in naturalistic productions (but see Jeretič 2018; Dieuleveut et al. 2019a). In this paper, we provide the first large-scale study of the development of modal force by examining the modal production of 12 children between the ages of 2 and 3. Our corpus and experimental results on children’s modals indicate an asymmetry in force acquisition. Children seem to master possibility modals early: at age 2, children use them frequently and productively, both with and without negation. And they use them in an adult-like way: crucially, they do not use them in necessity situations. However, they seem to struggle with necessity modals. They produce these much less frequently and, often, in a non-adult-like way: they use them in situations where adults prefer possibility modals. If this difficulty with necessity modals persists into the preschool years, it could explain children’s tendency in prior comprehension studies to both accept possibility modals in necessity contexts (they may lack a relevant stronger alternative) and necessity modals in possibility contexts (they may not be sure that these modals express necessity).

Together, our results from mothers’ and children’s productions seem to lead to a puzzle: if the conversational context is informative about both forces, why should children particularly struggle with necessity modals? The early advantage for possibility modals could be due to a combination of factors. First, possibility modals are more frequent than necessity modals in children’s input (about 3:1). Second, situations in which possibility modals occur with negation seem to be particularly informative (e.g., prohibitions, impossibilities), while negation may be particularly misleading with necessity modals. Whatever the reason for children’s difficulty with necessity modals, their successes with possibility modals and relative failures with necessity modals provide no evidence for a necessity bias. Given that a necessity bias is neither necessary, in view of the information available in the input, nor evidenced in children’s productions, we suggest that it is dispensable, even in the case of modals.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we provide some general background on modal force and its acquisition. We first give a brief overview of the semantics and pragmatics of modals in English and beyond, particularly as they relate to force, and discuss the possible learnability implications that these cross-linguistic considerations engender. We then turn to how modals interact with negation, and what this might entail for force acquisition. We then review the main relevant findings from the modal acquisition literature. In Sect. 3, we present our input study. We first provide a descriptive, quantitative assessment of the modals children hear: which modals occur and how often, and when they appear with negation and in other DE environments. We then present three input-based experiments that assess the general informativity of natural conversational contexts about modal force, by asking adult participants to guess a modal blanked out from a dialogue extracted from the corpus, following a modified version of the HSP (Gillette et al. 1999). In Experiment 1, the blanked modal statement is presented in context (seven preceding lines of dialogue); in Experiment 2, it is presented without the dialogue, with only the target sentence; and in Experiment 3, all content is removed, as the sentence is presented with content words replaced by nonce ‘Jabberwocky’ words. Our results show that the conversational context modals are used in is highly informative about both forces. We then probe what aspects of the conversational context might be helpful and identify one feature in particular for root modals, namely the desirability of the prejacent. A fourth experiment confirms that necessity—but not possibility—modals are typically used with undesirable prejacents. In Sect. 4, we turn to children’s productions. We first provide a quantitative assessment of the modals they produce and then present a fifth experiment that assesses the extent to which children use their modals in an adult-like way, by asking adult participants to guess the force of modals used by children. Our results suggest that children master possibility modals early but struggle with necessity modals. In Sect. 5, we discuss implications of our findings for how modal force acquisition might unfold in English and beyond. Section 6 concludes.

2 Background

2.1 Modal force in English and beyond

English modals come in two main forces: possibility and necessity. This is standardly captured by treating modals as existential or universal quantifiers over possible worlds, following the modal logic tradition. Further force distinctions can be found: necessity modals can be split into strong (must) vs. weak (should) necessity (von Fintel and Iatridou 2008);Footnote 4 nouns (slight possibility) and adjectives (likely) can encode even finer-grained strength distinctions. Here we focus on the main contrast between possibility and necessity modals and the learnability issues that it gives rise to.

Modals can be used to express different flavors of modality: epistemic modals (as in (2)) express possibilities and necessities given some evidence; deontic modals express possibilities and necessities given some relevant rules (as in (1)). We use the term ‘root’ modality (Hoffmann 1966) for all non-epistemic flavors. This distinction matters for us in that root modals tend to pattern together and differently from epistemic modals in their interactions with scope-bearing elements, notably negation.

-

(2)

In English, a modal always expresses the same force (possibility or necessity). However, it can be used for different flavors: Jo must draw can express an epistemic necessity (‘Jo is likely to draw’) or a teleological, bouletic, or deontic necessity (‘Jo needs/wants/is required to draw’). This is captured in a classical Kratzerian framework (Kratzer 1981, 1991) by having modals be lexically specified for force but not for flavor. Flavor gets determined by conversational backgrounds which specify the set of worlds that the modal quantifies over, as the lexical entries, slightly modified from Kratzer (1991), illustrate in (3).

-

(3)

According to Horn (1972), modals form scales (<candeontic, have todeontic>,<mightepi, mustepi>…),Footnote 5 and as such, they give rise to scalar implicatures. The use of (1a), for instance, can implicate that you don’t have to go this way; the use of (2a) can implicate that it doesn’t have to be raining. In the Gricean tradition (Grice 1975), this implicature arises from the assumption that the speaker is trying to be maximally informative but is not in a position to assert the relevant stronger statement in (2b). Speakers should prefer to use must p whenever they believe it to be true and relevant: listeners can then infer from the fact that the speaker did not chose the stronger (more informative) sentence that she must not believe it.

In Indo-European languages like English, possibility and necessity duals are common. However, various languages seem to lack such pairs. Instead, the same ‘variable force’ modals can be used in situations where English speakers would either use a possibility or necessity modal. Analyses vary in how to capture these variable force behaviors (see Yanovich 2016 for a summary). In St’át’imcets and Washo, modals have been analyzed as underlyingly necessity (universal) modals that can be weakened by contextually restricting their domain of quantification (Rullmann et al. 2008; Bochnak 2015). In Nez Perce, the modal o’qa has been analyzed as a possibility (existential) modal whose apparent variable force is due to the lack of a lexicalized stronger necessity dual in the language: o’qa does not belong to a Horn-scale, therefore its use is never associated with a scalar implicature (Deal 2011). Gitksan ima is similarly analyzed as a possibility modal (Peterson 2010; Matthewson 2013).Footnote 6

Turning back to our learning problem, the range of cross-linguistic variation we find suggests that there may be few constraints on the space of hypotheses learners have to entertain for modals. They can’t expect modals to come in duals, or that their language must have a possibility modal or a necessity modal. And even in a language with duals like English, knowing the force of one modal doesn’t guarantee that the next modal will express a different force, given that several lexemes can express the same force (e.g., can, might, and may): children will thus have to figure out force for each modal anew.

One aspect of the English modal system that could indirectly help the learner is that speakers may refrain from using possibility modals in necessity situations, since necessity modals would be more informative. If the situations in which possibility modals are used never overlap with those in which necessity modals are used, this could help English learners distinguish possibility from necessity modals. However, the extent to which adults always choose necessity modals over possibility modals in necessity situations is not entirely clear. Speakers do not always aim for maximal informativity: other conversational principles intervene. Possibility modals can be used, for instance, to soften statements in a polite way: ‘You could be a little quieter’ can be used as an order to be quiet, or ‘It might be too late’ to convey that it is too late (Searle 1969; Austin 1975; Grice 1975; Brown and Levinson 1987, a.o.). Note that these politeness considerations are peculiar to modals and do not arise, for instance, with quantifiers over individuals. If frequent enough, they could blur the distinction between possibility and necessity modals and be particularly misleading. One of our main goals here is to find out how clear the input is about the underlying force of modals in speech to children.

We now turn to the interaction of modals with negation and discuss the extent to which negative environments can help or hinder learners to figure out modal force.

2.2 Modals and negation

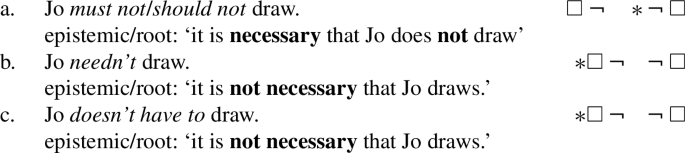

Sentences containing modals and negation can in principle receive two interpretations: a ‘strong’ interpretation (not > possible, logically equivalent to necessary > not), and a ‘weak’ interpretation (possible > not, logically equivalent to not > necessary). Cross-linguistically, epistemic possibility modals tend to be interpreted above negation and root possibility modals below (Coates 1988; Cinque 1999; Drubig 2001; Hacquard 2011; for a typological overview, see De Haan 1997; van der Auwera 2001). This is illustrated for English in (4a), (4b), and (4c): (root) can is interpreted below negation, and (epistemic) might is interpreted above negation; may is interpreted under negation with a root interpretation and over negation with an epistemic interpretation.

-

(4)

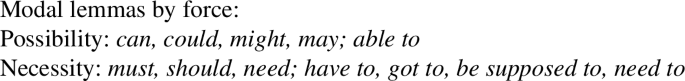

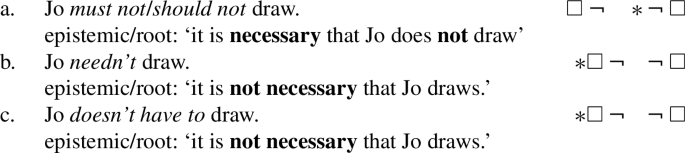

Necessity modals, on the other hand, seem to keep the same scopal behavior with respect to negation, regardless of flavor: they either systematically scope over negation, like must/should in (5a) (Dutch moeten, German müssen) (a behavior Iatridou and Zeiilstra 2013 attribute to their being Positive Polarity Items), or under negation, like need in (5b) and have to in (5c). English need, Dutch hoeven, and German brauchen are commonly analyzed as a Negative Polarity Items (NPIs).

-

(5)

Thus, modals are not uniform in their interaction with negation, force-wise or flavor-wise. This means that for at least some of the modals children have to learn, using negation to infer their force will be problematic. If they expect negation to scope over all modals by default (regardless of force and flavor), cases like (4b) and (4a) will be problematic: (4b) could suggest a necessity meaning for might (need not ∼ might not), and (4a) could suggest a possibility meaning for must (can’t ∼ mustn’t). If learners expect negation to scope over root modals but under epistemic modals (given some more general assumptions about flavor and scope),Footnote 7 (4b) is no longer problematic, but (5a) still is. Alternatively, if learners initially assume strong interpretations for any negated modal sentence (following Crain and Thornton’s 1998Semantic Subset Principle; see Moscati and Crain 2014),Footnote 8 cases like (5b), (5c), and (4b) will be problematic. For negation to be helpful in figuring out a modal’s force, learners would need to have already figured out how the modal scopes relative to negation and expect negation to scope differently based on force and flavor. However, it is not clear how they would figure out the right scope relations between modals and negation without knowing the force of the modals.

In the next section, we briefly review findings about children’s understanding of modal force and its interaction with negation from the acquisition literature.

2.3 Modal force acquisition

Possibility modals like can are found early in child productions, by age 2. The literature reports an asymmetry, with root modals appearing earlier than epistemics (Kuczaj and Maratsos 1975; Papafragou 1998; Cournane 2015, 2021; van Dooren et al. 2017).Footnote 9 Experimental work on children’s comprehension usually targets older children (age 4 and up) (Hirst and Weil 1982; Byrnes and Duff 1989; Noveck et al. 1996; Noveck 2001; Ozturk and Papafragou 2015, a.o.) and focuses on epistemic flavor, using felicity judgment tasks, where children have to judge whether a possibility or a necessity statement is true in scenarios where a toy is hidden in one of two boxes. By age 4, children seem to be sensitive to the relative force of modals, when the contrast is made salient by the experimental design, but they still do not behave like adults. First, they tend to over-accept possibility modals when necessity modals are more appropriate (Noveck 2001; Ozturk and Papafragou 2015). This is traditionally blamed on general difficulty with scalar implicatures (Chierchia et al. 2001; Barner and Bachrach 2010; Barner et al. 2011; Skordos and Papafragou 2016, a.o.): children have trouble accessing the relevant alternatives that the speaker takes for granted and using them to understand the implicature when asked to judge sentences in isolation. Second, children also tend to accept necessity modals in possibility situations (Ozturk and Papafragou 2015; Koring et al. 2018), a perhaps more surprising result from an adult’s perspective: whereas possibility modals are under-informative but logically true in necessity situations, necessity modals are false in possibility situations. Ozturk and Papafragou (2015) argue that children’s difficulty with necessity modals stems from (non-linguistic) difficulty reasoning about indeterminate events: in reasoning tasks that introduce indeterminacy, children tend to commit to a possible conclusion before decisive evidence is available and arbitrarily select one possibility over the other (a tendency sometimes referred to as premature closure; Bindra et al. 1980; Piéraut-Le Bonniec 1980; Acredolo and Horobin 1987; Robinson et al. 2006).

A few experimental studies focus on children’s interpretation of sentences containing negated modals (Moscati and Gualmini 2007 [can]; Gualmini and Moscati 2009 [need and Italian dovere ‘must’]; Moscati and Crain 2014 [Italian potere ‘can’]; Koring et al. 2018 [Dutch hoeven ‘need’]). Children tend to prefer strong interpretations of negated modal sentences (not>possible or necessary>not), even when adults prefer weak ones (possible>not or not>necessary). These studies assume that children already know the underlying force of their modals and focus on their scope relative to negation. However, children’s non-adult-like responses could, in principle, be explained by not knowing the force of the modals involved. For instance, one predicts the same responses for Italian potere non (where the possibility modal scopes over negation, leading to a weak interpretation) if children assume that potere expresses possibility and negation scopes over the modal or if they assume that potere expresses necessity and negation scopes under the modal.

We now turn to our studies, which probe more directly the questions of when and how children figure out modal force by investigating their modal input (Sect. 3) and their early productions (Sect. 4).

3 Children’s modal input

The goal of this study is to provide an analysis of the modals children are exposed to. We first present quantitative results from a corpus study: how are possibility and necessity modals distributed in actual speech to children? How frequently do they occur with negation? We then present four experiments, using corpus data, aimed at assessing the informativity of the conversational context as to force. In Experiment 1, based on the HSP (Gillette et al. 1999), participants have to guess the force of a missing modal in dialogues extracted from the corpus, allowing us to assess the general informativity of conversational contexts depending on force, negation, and flavor (epistemic vs. root). Experiment 2 isolates the role of context from possible biases toward possibility or necessity meanings, by showing participants the blanked modal sentence without the dialogue, while Experiment 3 shows the same sentence with all content words replaced by ‘Jabberwocky’ nonce words. Experiment 4 focuses on a particular feature of the context, namely the desirability of the prejacent as a cue to force for root modals.

3.1 Corpus study

3.1.1 Methods

We used the Manchester Corpus (Theakston et al. 2001) of UK English (CHILDES database, MacWhinney 2000), which consists of 12 child-mother pairs (six females; age range: 1;09-3;00) recorded in unstructured play sessions. We chose this corpus for its relative density and uniformity of sampling and early age range. We focused on the period between ages 2;00 and 3;00. All utterances containing modal auxiliaries and semi-auxiliaries (26,598 of 564,625 total utterances; adult: 20,755; child: 5,842; excluding repetitions [6.6%]: adult: 19,986; child: 4,844) were coded for force (possibility vs. necessity) (6), presence of negation (7), and flavor (epistemic vs. root) (8).Footnote 10 We did not include will, would, shall, or going to as they primarily express future, for which force is a matter of debate (Stalnaker 1978; Cariani and Santorio 2017, a.o.).

-

(6)

-

(7)

-

(8)

3.1.2 Results

We found that, overall, possibility modals were more frequent than necessity modals in adult speech: they represent 72.5% of all adults’ modal utterances (Table 1). This is mostly driven by the highly frequent modal can.

Turning to negation and other DE contexts, we found that possibility modals occur with negation more frequently than necessity modals (possibility: 20.9% vs. necessity: 10.1%). For necessity modals, negation occurs proportionally more frequently with modals that out-scope negation (should: 22.8%; must: 15.8% vs. have-to: 4.5%; got-to: 1.1%). Modals rarely occur with other negative quantifiers (e.g., nothing/never), with no difference between possibility and necessity (possibility: 0.2%; necessity: 0.1%), or under a negated embedding verb (e.g., don’t think), again with no difference between possibility and necessity (possibility: 1.5%; necessity: 2.1%). Details of negative environments are provided in online Appendix A (Table 10). We further found that modals are extremely rare in antecedents of conditionals (0.6% of adults’ modal utterances). Necessity modals almost never occur in such environments: we found only 15 occurrences in the whole corpus (106 possibility modals), with seven of them corresponding to ‘if you must’. As a point of comparison, 135 necessity modals occur in consequents of conditionals vs. 432 possibility modals. A breakdown by modal is provided in online Appendix A (Table 11).

Overall, epistemic uses of modals are rare: they represent only 8.8% of all adults’ modal utterances (Table 2). Negation is significantly more frequent on root than on epistemic modals (epistemic: 4.6% vs. root: 19.1%). A breakdown by modal is provided in online Appendix A (Table 12).

3.1.3 Interim discussion

Overall, possibility modals are more frequent than necessity modals in mothers’ speech: children thus have more opportunities to learn them. The relative rarity of necessity modals may be due to the alternative ways speakers can express necessity (e.g., using imperatives for deontic necessity or asserting the prejacent directly for epistemic necessity).

Necessity modals rarely appear in DE environments. Negation is infrequent with necessity modals: only 10.1% of all necessity modals cooccur with negation (vs. 20.9% of possibility modals), and necessity modals are exceedingly rare in antecedents of conditionals.

3.2 Experiment 1: Adults’ modal productions

To assess the general informativity of natural conversational contexts about force, we implemented a variant of the HSP (Gillette et al. 1999) using dialogue contexts extracted from the corpus. The goal of the original HSP (Gillette et al. 1999; see also Snedeker 2000; Snedeker et al. 1999; White et al. 2016) is to compare the effect of different kinds of contextual information on the ability to recover a word’s meaning: extralinguistic scenes, associated words and morphemes, or syntactic-frame information. The accuracy with which participants can recover the actual word given the context is taken as a general measure of informativity of properties of that context. Following Orita et al. (2013), we use the paradigm in a slightly different way: participants were given only written transcripts from the corpus (with no visual or acoustic information) and had to choose between a possibility and a necessity modal.Footnote 11 This allows us to, first, give a general measure of the informativity of conversational context about force: can naïve subjects guess the force of a blanked-out modal based solely on excerpts of conversations in which it appears? Second, we can test directly for interrelationships between force and negation: are contexts equally informative for both necessity and possibility modals? Are negative contexts more informative than positive contexts?

3.2.1 Methods

Procedure. The experiment was run online on IBEX Farm.Footnote 12 Participants recruited via Amazon MechanicalTurk were asked to guess a redacted modal in a dialogue between a child and mother by choosing between two options, corresponding either to a possibility (e.g., might) or a necessity (e.g., must) modal, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. All dialogue contexts consisted of the modal sentence with a blank and seven preceding utterances, with two options displayed at the bottom of the screen. There was first a short training where participants had to choose between definite and indefinite articles (the vs. a) (three examples with feedback), followed by the test phase without feedback. Overall, each participant had to judge 40 different dialogues (20 trials: 10 possibility, 10 necessity; 20 controls using tense: 10 past, 10 future), presented in random order. The 20 trials were selected randomly for each participant from a list of 40 contexts originally extracted from the corpus; the 20 controls were the same for all participants. Further details of the instructions and material are provided in online Appendix B.

Conditions. We tested force (possibility vs. necessity) within participants, and flavor (root vs. epistemic) and negation (present vs. absent) between participants. Negation was tested only for root flavor because negated epistemics were too rare in the corpus (Table 2). Table 3 summarizes the experimental design.

Material. Extraction procedure—160 contexts (2∗20 per condition) were randomly extracted from the corpus for each modal (can, able, might, must, have to). Exclusion criteria—We excluded contexts where the adult or child used the target modal in preceding utterances. Contexts were not excluded when the adult or the child used another non-target modal. Briticisms, such as willn’t, were removed from the dialogue and replaced with the American English equivalent (e.g., won’t). We didn’t exclude contexts where there were tag questions (e.g., ‘…, mustn’t she?’), but we removed tags when they occurred in the target sentence. Controls—Participants had to choose between future and past (e.g., [saw] vs. [will see]; see Fig. 1b). Importantly, the correct answer was not always guessable based on the target sentence alone: participants were required to read the entire dialogue. Extraction procedure and data cleaning were the same as for the targets. We excluded participants that were less than 75% accurate on controls.

3.2.2 Results

Participants. We recruited 289 participants on Amazon Mechanical Turk (four groups among participants: root-aff-1: 73, root-aff-2: 72; root-neg: 73; epi-aff: 71; language: US English; 156 females, mean age = 40.6-years-old). We removed from analysis eight participants (2.8%) who were less than 75% accurate on controls. We thus present results for 281 participants (root-aff-1: 71, root-aff-2: 69; root-neg: 70; epi-aff: 71).

Analysis. All data analyses were conducted using R (R Core Team 2013) and the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2014). All R scripts for analysis are available at https://osf.io/v9ure/. Figure 2 summarizes the mean accuracy for each condition.Footnote 13 Overall, participants were highly accurate at guessing modal force (general mean accuracy: 79.9%). We first ran binomial tests to see whether they differ from chance for each condition (Table 4). Participant accuracy significantly differs from chance in each condition. The lowest performance was found for root-neg necessity modals (e.g., not have to) (61.3%). Force—To test whether there was an effect of Force, we fitted a generalized linear mixed effects model, built with a maximal random effect structure, testing Accuracy (dependent variable, binomial), with Force as a fixed effect and Subject and Item as random factors (following Barr et al. 2013) (glmer syntax: Accuracy∼Force+(Force|Subject)+(1|Item),Footnote 14 first overall and then subsetting the data for each condition. We compared these models with a reduced model without Force as a fixed effect (Accuracy∼1+(Force|Subject)+(1|Item)).Footnote 15 We found a general effect of Force, in the direction of a higher accuracy for possibility contexts (Model Comparison: \(\chi^{2}(1)=20.49\), p = 5.9e-6∗∗∗).Footnote 16 Restricting to each comparison group, we found a significant effect in root-aff-1 (\(\chi^{2}(1)=61.1\), p = 5.5e-15∗∗∗) and root-neg (\(\chi^{2}(1)=15.6\), p = 7.8e-05∗∗∗), again in the direction of a higher accuracy for possibility contexts. In epi-aff, the effect of Force almost reached significance (\(\chi^{2}(1)=3.73\), p = .053 (NS)). In root-aff-2, it was not significant (\(\chi^{2}(1)=6\)e-04, p = 0.98 (NS)). Negation—We compared root-aff-2 and root-neg, as these conditions included the same lemmas. We used the same method as above, comparing a model with Negation as a fixed effect and Subject and Item as random factors to a model without Negation as a fixed effect (Maximal model: Accuracy∼Negation+(1|Subject)+(1|Item); for the interaction: Accuracy∼Force∗Negation+(1|Subject)+(1|Item)). We found a strong interaction effect (Interaction Force∗Neg: \(\chi^{2}(1)=7.9\), p = 0.0047∗∗). We found a significant effect of negation on necessity modals, which led to lower accuracy (have to vs. not-have to: \(\chi^{2}(1)=6.5\), p = 0.011∗). On possibility modals, negation led to higher accuracy, but the effect was not significant (can vs. can’t: \(\chi^{2}(1)=2.29\), p = 0.13 (NS)). Flavor—There was no effect of flavor (\(\chi^{2}(1)=0.11\), p = 0.74 (NS)) (Maximal Model: Accuracy∼Flavor+(1|Subject)+(1|Item)).

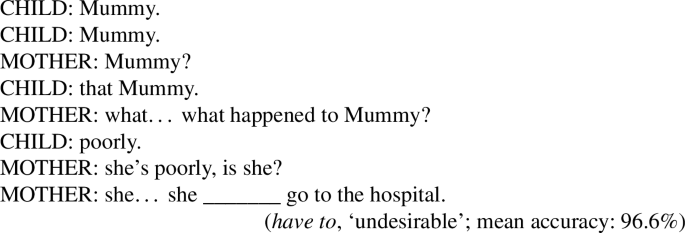

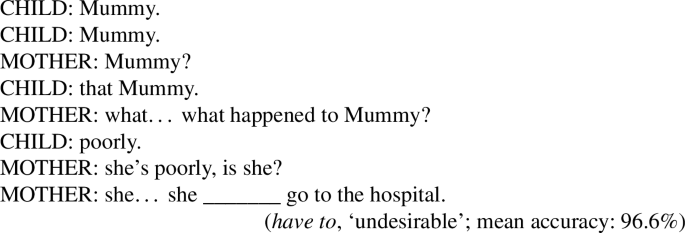

Analysis by contexts (post-hoc). To get a sense of the kinds of contextual cues that were particularly helpful, we examined the contexts that led to the lowest and highest accuracy for both root and epistemic flavors. We focused on necessity modals, as there was more variability in accuracy for necessity modals. This informal analysis revealed two factors, depending on flavor: for root modals, cases where the proposition expressed by the prejacent seemed undesirable (e.g., going to the hospital) or effortful (e.g., lifting a heavy object) seemed to lead to high accuracy for necessity modals (see (9)). For epistemic modals, we found high accuracy for necessity modals in contexts that made salient robust evidence for the prejacent (see (10)). Our post-hoc analysis also pointed out a particularly high accuracy for possibility root modals in interrogative sentences (e.g., ___ you see?) (mean accuracy for root possibility modals in interrogative: 96.0%).Footnote 17 In this case, accuracy may not reflect pure informativity, as participants may rely on idiomatic turns of phrases. However, they were still very accurate in contexts that did not involve interrogatives (mean accuracy for root possibility in declaratives: 76.3%).

-

(9)

-

(10)

3.2.3 Interim discussion

Results from Experiment 1 show that the conversational context is informative about force: participants were able to guess the force of the modal accurately, just based on short conversation transcripts, and for both forces (general mean accuracy: 79.9%; possibility modals: 87.5%; necessity modals: 72.3%). This means that the information is there, at least in principle, for learners to figure out modal force based on context alone. If children are sensitive to the same cues as adults, they may not need to rely on negation or on a bias toward necessity meanings to figure out force.

Multiple factors may play a role in making the conversational context useful for guessing the right modal force: situational cues (e.g., who the interlocutors are), cues from world knowledge (e.g., what is allowed or prohibited), or pragmatic cues (what the speaker is trying to achieve, in particular performing orders, permissions, or prohibitions). Our post-hoc exploration suggests that cues may vary based on modal flavor. It appears that the (un)desirability and effortfulness of the prejacent could be particularly useful for roots, and some explicit justification for epistemics. We probe the effect of desirability more directly in Experiment 4 below.

Of course, some of the cues available to adults in this experiment might not to be usable by children: for instance, children might lack some world knowledge. This limitation is intrinsic to any paradigm where adults are used to simulating word learning (the task asked of adults is to guess a word they already know, whereas children have to guess the meaning of a new word from the context in which it is used) (see Orita et al. 2013; White et al. 2016 for discussion). That said, children also have access to a substantially richer context than participants in our experiment, who had no visual or prosodic information and no common ground with the child and the mother.

We found a general effect of force, with participants being more accurate with possibility modals. This could be interpreted as possibility contexts being more informative than necessity contexts. However, the effect was carried by only two sub-conditions (root-aff-1 and root-neg; it was near-significant in epi-aff (\(\chi^{2}(1)=3.73\), p = .053), and not significant in root-aff-2). It was not significant once we took into account the effect of interrogative sentences, which led to a very high accuracy for root possibility modals (if we restrict to declarative contexts only, participants don’t perform significantly better in possibility contexts).Footnote 18

Lastly, turning to negation, we found that negated necessity modals are rare: our corpus results show that overall, modals scoping under negation were negated 7.4% of the time (vs. 22.6% for root possibility modals).Footnote 19 The results from Experiment 1 show that they are also less informative. We found opposite effects of negation on possibility and necessity modals: while negation led to a slightly higher accuracy for possibility modals (can’t: 89.5% vs. can: 81.5% (NS)), it led to lower accuracy for necessity modals (don’t have to: 61.3% vs. have to: 82.0%, p = 0.011∗) (significant interaction effect Force*Negation: p = 0.0047∗∗).

Why is that so? First, the low frequency of negated necessity modals may come from a competition with the use of a bare possibility modal, which can convey non-necessity via a scalar implicature (Horn 1972).Footnote 20 We found a few cases that could be informative for children, like (11), where the context makes clear that the impossibility interpretation does not hold.

-

(11)

However our results suggest that most adult negated necessity modals are cases like (12), where the conveyed meaning is close to impossibility, which illustrate ‘polite’ uses of negated necessity modals. Here, don’t have to is used to perform a prohibition.

-

(12)

From this, we conclude that it is unlikely that children rely on negation to figure out the force of necessity modals. First, as discussed earlier, negation is potentially misleading for a number of necessity modals: mustn’t is truth-conditionally equivalent to can’t, which might drive children to infer that they express possibility, if children assume that negation scopes over root modals by default. Second, necessity modals that can scope under negation (e.g., have to, got to) are rare in the input, and their use is particularly misleading about their force because they often can be used to convey impossibility. Children will therefore need other strategies to solve the subset problem. However, our findings suggest that negation could be more helpful to figure out the force of possibility modals: they cooccur frequently in the input (22.6% of root possibility modals are negated), and Experiment 1 shows that impossibility contexts are highly informative (mean accuracy for can’t: 89.5%). Children may be able to infer from these occurrences the force of possibility modals if they expect negation to scope over modals.

3.3 Experiments 2 and 3: Isolating the role of context

Experiment 1 shows high accuracy for both possibility and necessity. We take these results to mean that the context is informative as to force. But could it be that participants succeed at the task not by relying on the context, but through biases, which could also be at play in children’s modal learning? In particular, could their high accuracy be due to a necessity bias that allows them to correctly guess necessity meanings?Footnote 21 To isolate the contribution of the dialogue context, we ran two related follow-up experiments, presenting either only the target sentence without its discourse context (Experiment 2, ‘sentence-only’) or only the target sentence, but replacing all content words with nonce words (Experiment 3, ‘Jabberwocky’). We expected that participants’ performance should decrease in Experiments 2 and 3, if their successes in Experiment 1 were due to a reliance on context.

3.3.1 Methods

Procedure. Experiments 2 and 3 were identical to Experiment 1, except that in Experiment 2, participants only saw the target sentence (without the preceding dialogue; see Fig. 3a), and in Experiment 3, they saw only the target sentence with all content words replaced by Jabberwocky (see Fig. 3b).Footnote 22 Experiment 2 lets us isolate the specific contribution of the dialogue. However, it does not remove all contextual information, since the content of the prejacent contributes to context (e.g., desirability of the event it describes). This motivates Experiment 3, which further removes any semantic information in the sentence (see Gillette et al. 1999; White et al. 2016, a.o.). As the task was shorter, participants judged all 40 contexts (Experiment 2: 60 trials: 20 possibility; 20 necessity; 20 controls using tense; Experiment 3: 40 trials: 20 possibility; 20 necessity). To make sure that participants kept paying attention, we also had eight attention checks (simple additions and subtractions, e.g., 1 + 3 = _____). We removed from target sentences any repetitions (e.g., ‘dolly… dolly _____ use her potty’ was corrected to ‘dolly _____ use her potty’), as well as phatic words (e.g., oh, yeah). For Experiment 3, we replaced all content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs) with nonce Jabberwocky words (e.g., shink, gumbly). We kept all function words (determiners, prepositions, complementizers, connectives, personal pronouns, temporal adverbs, and locatives), auxiliaries (be, have, modals, semi-modals, other than the target modal, which was replaced by a ____), plural morphology, and tense and aspect marking. Conditions were the same as in Experiment 1. Instructions are provided in online Appendix B.

3.3.2 Results

Participants. We recruited 252 participants on Amazon Mechanical Turk (Experiment 2: root-aff-1: 31, root-aff-2: 33; root-neg: 30; epi-aff: 29; 66 females, mean age: 44.0 years; Experiment 3: root-aff-1: 31, root-aff-2: 29; root-neg: 30; epi-aff: 38; 67 females, mean age: 38.8 years). In Experiment 2, we removed from the analysis one participant who was less than 75% accurate on attention checks and six participants who were less than 75% accurate on tense controls (5.7%).Footnote 23 In Experiment 3, accuracy on attention checks was very high (99.1%). No participant was excluded.

Analysis. Tables 5a and 5b report mean accuracy in each condition for Experiments 2 and 3. Like Experiment 1, we first ran binomial tests to see whether they differ from chance for each condition. In Experiment 2, participants were overall still good at guessing force (Table 5a). In Experiment 3, participants were above chance for possibility modals, but didn’t differ from chance for necessity modals, except in epi-aff (Table 5b). We used generalized linear mixed effect models to test the effect of Experiment on Accuracy, first overall and then subsetting the data to test by each subcomparison group, comparing Experiments 2 and 1, Experiments 3 and 2, and Experiments 1 and 3. We tested Accuracy (dependent variable), with Experiment as a fixed effect and Subject and Item as random factors (Maximal model: Accuracy∼Experiment+(1|Subject)+(1|tem)). We compared these models with a reduced model without Experiment as a fixed effect (Accuracy∼1+(Force|Subject)+(1|Item)). First comparing Experiments 1 and 2, we found that participant performance is overall lower without the dialogue (\(\chi^{2}(1)=48.2\), p = 3.9e–12∗∗∗). Looking at the eight subcomparision groups, we found decreased performance for necessity contexts in root-aff-1, root-aff-2, and epi-aff and for posibility contexts in root-aff-2 and root-neg. We found no difference for possibility root-aff-1 and epi-aff and necessity root-neg. Detailed results of the comparisons are given in online Appendix D. Comparing Experiments 2 and 3, we found a significantly lower accuracy for Experiment 3 overall (\(\chi^{2}(1)=188\), p<2.2e–16∗∗∗) and looking at each subcomparison group. Last, comparing Experiments 1 and 3, we also found decreased performance for Experiment 3 overall (\(\chi^{2}(1)=650\), p<2.2e–16∗∗∗) and in each subcomparison group (see online Appendix D). Figure 4 summarizes the comparison between the three experiments for all conditions.

3.3.3 Discussion

These two control experiments let us isolate the specific contribution of context and show that it is informative beyond potential biases. In the Jabberwocky version (Experiment 3), participants’ mean accuracy was 57.2% vs. 74.0% when they saw the sentence with content words (Experiment 2), and 79.9% when they saw the preceding dialogue (Experiment 1). This first confirms that syntax alone doesn’t help: when we removed all semantic information, subjects were at chance.Footnote 24 Moreover, further analysis looking at the interaction between Force and Experiment (reported in online Appendix D, Table 16) suggests that the effect of having more contextual information is stronger for necessity modals than for possibility modals. If participants’ high accuracy in Experiment 1 was due to a necessity bias, we would expect their performance to remain the same in Experiment 2: participants should guess necessity meanings, unless presented with direct evidence against it. Altogether, participants’ high accuracy on possibility modals, even in the absence of context, suggests that if they bring a force bias to the task, it is more likely to be a possibility, rather than a necessity, bias.

3.4 Experiment 4: Desirability

The results from Experiments 1-3 argue that the conversational context in which modals are used is informative about their force. But what is it about the context that is particularly informative? As discussed in Sect. 3.2.3, several factors could be at play. Our post-hoc analysis suggested that the cues may vary with flavor: for root modals, necessity modals seem associated with undesirable and effortful events; for epistemics, necessity modals seem to occur in contexts that highlight strong evidence that support the proposition expressed by the prejacent. We now turn to an experiment that tests the hypothesis that (un)desirability matters for root modals, as an initial proof of concept, and leave a more systematic probing of additional features of the context for future research.

We hypothesize that the desirability of the prejacent could be playing a crucial role in the acquisition of force for root modals. Desirability is a feature likely to be conceptually accessible to young children: the cognitive developmental literature suggests that children can reason about desires quite early on and understand that people can have incompatible desires (Wellman and Woolley 1990; Repacholi and Gopnik 1997; Rakoczy et al. 2007; Ruffman et al. 2018, a.o.). Moreover, preschool children have been shown to be sensitive to desirability for modal usage pragmatics, in particular compared to unmodalized expressions (Ozturk and Papafragou 2015). The first goal of Experiment 3 is to assess the availability of this cue in the input: do adults actually use necessity modals more frequently with undesirable events (e.g., ‘You must/#can eat your brussels sprouts’) and possibility modals with desirable events (e.g., ‘You can/#must have a cookie’)? Second, does this contribute to participants’ performance in Experiment 1, i.e., do adults actually rely on this cue to guess force?

3.4.1 Methods

Procedure. Participants were asked to indicate whether various activities (e.g., ‘doing a puzzle’) sounded fun or not (see Fig. 5). They were told that the activities involved 2-year-old children and their mothers. The different activities corresponded to the prejacentsFootnote 25 of the modals tested in Experiment 1:Footnote 26 for example, for ‘Can the dolly ride on Aran the horse?’, participants were asked whether ‘riding on Aran the horse’ sounded fun (‘yes’) or not (‘no’). We used the prejacents, rather than full modal sentences to avoid biasing toward positive responses for possibility modals and toward negative responses for necessity modals. Referential pronouns (e.g., it) were replaced whenever they could be recovered from the context (e.g., ‘Finding the green marker’ for ‘Can you find it?’). In each group, participants judged all 40 prejacents (42 trials: 20 possibility, 20 necessity; 2 initial practice items, which were removed from the analysis). To make sure participants kept paying attention, we had 10 attention checks (e.g., 1 + 3 = ____). Instructions are given in online Appendix B. As our hypothesis concerns root modals, we ran the experiment only on Root-aff-1 (can vs. must) and Root-aff-2 (can/able vs. have to). Rationale—This experiment allows us to first assess the desirability of the different events in as objective a way as possible, to see if there is a relation between desirability (measured by the proportion of yes answers to ‘being fun’, a child-friendly way of assessing what is desirable) and force usage in the corpus. We can then probe whether adults used this cue to infer force in Experiment 1 by looking at the correlation between the desirability score in Experiment 4 and accuracy in Experiment 1. We expect a negative correlation for necessity modals (fewer ‘yes’ responses for accurate guesses of necessity uses) and a positive one for possibility modals (more ‘yes’ responses for accurate guesses of possibility uses).

3.4.2 Results

Participants. We recruited 70 participants on Amazon Mechanical Turk (root-aff-1: 35, root-aff-2: 35; language: US English; 35 females, mean age: 40.4 years). Accuracy on attention checks was very high (99.6%), and we did not have to remove any participant from the analysis based on attention checks.

Analysis. Table 6 reports means of ‘yes’ answers (‘fun’) in all conditions. First, to test for the effect of Force (possibility vs. necessity), we fitted a generalized linear mixed effects model, testing Answer (dependent variable), with Force as a fixed effect and Subject and Item as random factors. We compared this model with a model without Force as fixed effect (glmer syntax for the maximal model: (Answer)∼Force+(1|Subject)+(1|Item); for the reduced model: ((Answer)∼1+ (1|Subject)+(1|Item)). ‘Fun’ answers were coded as ‘1’. We found a general effect of Force: participants judged prejacents extracted from possibility statements overall more ‘desirable’ than those extracted from necessity statements (Model comparison: \(\chi^{2}(1)=15.5\), p = 8.2e–05∗∗∗). We subsetted the data for each group, using the same formulae and comparison methods. The effect is significant in both groups (root-aff-1: \(\chi^{2}(1)=8.2\), p = 0.0041∗∗; root-aff-2: \(\chi^{2}(1)=6.2\), p = 0.012∗).Footnote 27 Figure 6 shows the distribution of ratings for possibility and necessity for the two groups. Then, we computed correlations between the desirability score (Experiment 4) and accuracy in Experiment 1 (see Fig. 7). For possibility, we found a weak positive correlation (Pearson’s r = 0.12) (t(1398)=4.42, p<0.001∗∗; 95%-CI: [0.065; 0.168]); for necessity, a weak negative correlation (Pearson’s r = −0.073) (t(1398)=−2.74, p = 0.0063∗∗∗; 95%-CI: [−0.125; −0.021]).

3.4.3 Discussion

Our results confirm our initial observations for Experiment 1 and show that there is a relation in children’s input between the desirability of the prejacent (evaluated by participants who were blind to the force of the modal originally used) and force. Adults use possibility modals more frequently with desirable events and necessity modals more frequently with undesirable events (mean desirability score for possibility modals [can/able]: 52.9%; for necessity modals [must/have to]: 28.6%). Furthermore, the lower accuracy for possibility modals with undesirable prejacents in Experiment 1 and for necessity modals with desirable prejacents suggests that adult participants in Experiment 1 likely made use of desirability in their force judgments. Together, this suggests that children could conceivably use this cue: it is available in the input, and the cognitive developmental literature suggests they are sensitive to desirability, though its association with obligations may require some life experience.

3.5 Summary: Children’s modal input

Our corpus results show that children are exposed to many more possibility modals than necessity modals and that they hear the former relatively more often with negation than the latter. We have also seen that negation is unlikely to help learners figure out necessity modals and might in fact hinder their acquisition. It appears, however, to be potentially much more helpful for possibility modals. If learners can’t rely on negation or other DE environments to solve the subset problem, do they need to rely on a necessity bias? Our experiments suggest that they may not need to, as the conversational context in which modals are used is informative about both forces. If children are able to make use of these conversational cues, they need to rely on neither negation nor a necessity bias. One aspect of the context that could be particularly helpful for root modals is the desirability of the prejacent. Now that we have a clearer picture of children’s modal input, and what, in principle, learners may be able to rely on or not, we turn to our study of children’s productions.

4 Children’s modal productions

To study children’s modal production, we used the same methods as for the input study. We first present the results from our corpus analysis, comparing children’s early productions to those of adults’, and then present results from Experiment 5, which is based on the same paradigm as Experiment 1, but tests children’s utterances.

4.1 Corpus study

4.1.1 Results

Like the adults, children produce more possibility modals than necessity modals, and the difference is even stronger (79.3% of children’s modal productions vs. 72.5% of adults’) (Table 7). Can is by far their most common modal (75.6% vs. 57.3% of adults’), and have to is their most frequent necessity modal (7.3% vs. 12.0% of adults’). Necessity modals are particularly rare with negation in their productions (only 5.1%), whereas negated possibility modals are very frequent: 51.0% (adults: necessity modals with negation: 10.1%; possibility modals with negation: 20.9%). Epistemic modals are overall very rare in child productions: they represent only 2.4% of children’s modal utterances (114 cases, possibility: 93, necessity: 21) vs. 8.8% of all adults’ modal utterances. Looking at the evolution of children’s productions during the time period, summarized in Fig. 8a, we find that the relative proportion of necessity modals tends to increase with age: while they represent 12% of children’s modal productions between 2 and 2;03, they represent 24.5% between 2.9 and 3 (Fig. 8b confirms that for adults, the relative proportion of possibility and necessity modals does not significantly change over time: we only find a slight increase of necessity modals).

4.1.2 Discussion

We found that children use (root) possibility modals frequently, both with and without negation, which we can take as initial evidence of productivity (Stromswold 1990). Children produced few necessity modals, and rarely with negation.Footnote 28 This difference might be explained by several factors: the difference in frequency in their input (if children grasp more frequent words first) and the differences in social status and topics of conversations between children and adults (for instance, children may be less prone to giving orders and thus less prone to using root necessity modals). Necessity modals tended to become more frequent over time. However, quantitative production data can only provide a partial picture of whether children use and understand modals correctly. To assess these productions in a more qualitative way, we ran Experiment 5 (identical in method to Experiment 1) on children’s modals.

4.2 Experiment 5: Children’s modal productions

The goal of this experiment was to investigate children’s early modal productions to see whether they use modals in an adult-like way, by comparing their usage to adult usage (Experiment 1). Can adults guess the force of a modal used by a child, given the conversational context in which they use it?

4.2.1 Methods

Experiment 5 was identical to Experiment 1, except that we used children’s utterances instead of adults’ and made small changes in the instructions (see online Appendix B).Footnote 29 An example of the display is given in Fig. 9. We implemented the same conditions: root-aff-1, root-aff-2, root-neg, and epi-aff. Controls were also based on tense (past vs. future). Extraction procedure—Given the low frequency of negated necessity modals and epistemic necessity modals in child productions, we could test only 10 different contexts for root-neg necessity and 12 contexts for epi-aff necessity conditions.Footnote 30 This did not make a difference for the participants, who always had 10 contexts to judge per condition (40 dialogues in the whole experiment: 20 trials: 10 possibility, 10 necessity; 20 controls: 10 past, 10 future). In all other conditions, 10 contexts were selected randomly out of a list of 20 contexts initially extracted from the corpus, in the same way as for the adult experiment. Exclusion criteria—Given the low frequency of negated necessity and epistemic modals, we did not remove cases where the modal already appeared in the preceding dialogue.Footnote 31 We made sure to include examples in the training (the/a) and control items (past/future) where the right (or wrong) answer appeared in the preceding dialogue. Again, we removed Briticisms, but we did not correct children’s ungrammatical utterances (e.g., comed for came), except in the case of have to when children omitted to (so that participants would not reject the answer because of its ungrammaticality). Rationale—We made the assumption that adults rely on their own competence to judge usage and that the dialogues preceding the modal sentence are equally informative for adults’ and children’s utterances.Footnote 32 If children use their modals in an adult-like way, we expect no difference in accuracy between Experiment 5 and Experiment 1. If they do not (e.g., they use can in a necessity situation when adults would use must, or they use must in a possibility situation when adults would use can), we expect a lower accuracy for children’s utterances.

4.2.2 Results

Participants. We recruited 289 participants on Amazon Mechanical Turk (epi-aff: 74, root-aff-1: 72, root-aff-2: 73; root-neg: 72; language: US English; 173 females, mean age=40.2-years-old). We removed 18 participants (6.2%) who were less than 75% accurate on controls.Footnote 33 We thus present results for 273 participants (epi-aff: 68; root-aff-1: 70; root-aff-2: 70; root-neg: 65).

Analysis. Table 8 reports mean accuracy in each condition (summarized in Fig. 10). We first ran the same binomial tests as for Experiment 1. Participants performed better than chance in all conditions involving possibility, but not necessity: for root-aff-2 (have to) (mean accuracy: 42.6%) and root-neg necessity (not have to) (mean accuracy: 32.3%), they performed lower than chance (Table 8). Force—We used generalized linear mixed effects models testing Accuracy with Subject and Item as random factors, comparing a model with Force as fixed effect to a model without it (Maximal model: Accuracy∼Force+(Force|Subject)+(1|Item)). The difference is significant in all conditions, with higher accuracy for possibility modals (Model comparison: all: \(\chi^{2}(1)=20.49\), p = 5.9e–6∗∗∗; root-aff-1: \(\chi^{2}(1)=60.4\) p = 7.7e–15∗∗∗; root-aff-2: \(\chi^{2}(1)=7.37\) p = 0.0066∗∗; root-neg: \(\chi^{2}(1)=38.1\), p = 6.6e–10∗∗∗; epi-aff: \(\chi^{2}(1)=7.93\) p = 0.0048∗∗). Negation—We compared root-aff-2 and root-neg, as they included the same lemmas. We used the same method, comparing a model with Negation as fixed effect to a model without it (Maximal model: Accuracy∼Negation+(1|Subject)+(1|Item); for the interaction: Accuracy∼Force∗Negation+(1|Subject)+(1|Item)). We found a significant difference (can vs. can’t: \(\chi^{2}(1)=3.65\), p = 0.056∗; have to vs. not-have-to: \(\chi^{2}(1)=6.74\), p = 0.0093∗∗; Interaction Force∗Neg: Accuracy∼Force*Group+(1|Subject)+ (1|Item): \(\chi^{2}(1)=9.24\), p = 0.0024∗∗). Flavor—There was no effect of flavor (\(\chi^{2}(1)=0.14\), p = 0.71). Age (adult vs. child usage)—We then tested for the effect of Age (adult vs. child usage), first overall and then for each subcondition (Accuracy∼Experiment+(1|Subject)+(1|Item)). We found a significant difference, with an overall lower accuracy for child usage (\(\chi^{2}(1)=260.5\), p<.001∗∗∗). Among possibility conditions, only root-aff-1 was significant; among necessity conditions, all comparisons were significant except epi-aff (Table 9). We found a strong interaction Force*Age: the difference in accuracy between possibility and necessity modals for child productions was larger than for adult productions (\(\chi^{2}(1)=46.2\), p = 1.06e–11∗∗∗).

4.3 Discussion

Even if participants were less accurate than when judging adults’ modals, they were good at identifying possibility modals used by children, for both flavors (mean accuracy on all possibility modals: 82.1% vs. 87.5% when judging adult modals). Participant performance for necessity modals was much lower (only 50.1%, vs. 72.3% for adult modals), especially for negated uses (32.3%). Examples like (13) and (14), which led to particularly low accuracy, illustrate children’s non-adult-like uses of necessity modals with and without negation (and confirm that the effect is likely not just due to participants expecting children to use possibility modals more often than necessity modals).

-

(13)

-

(14)

Together, these results suggest that children master possibility modals early, as they use them in an adult-like way. Their necessity modals, however, seem delayed: children do not use them in an adult-like way, suggesting that they either haven’t mastered their underlying force yet or have difficulty deploying them in the right situations. But if the difficulty with necessity modals we observe here for 2-to-3-year-olds persists into the preschool years, it could explain both types of over-acceptance found in comprehension studies: children would accept necessity modals in possibility contexts because they haven’t mastered their underlying force and accept possibility modals in contexts where adults prefer necessity modals because they lack a stronger alternative (i.e., they have not yet worked out scale-mate relations for English modals).

Importantly, we found no evidence in favor of a necessity bias. Children’s highly adult-like uses of possibility modals might even suggest a bias toward possibility. Note that this lack of evidence doesn’t necessarily entail that children don’t rely on a necessity bias when acquiring modals.Footnote 34 It’s conceivable that children use the bias to acquire necessity modals, but fail to use them in an adult-like way for independent reasons, as alluded to above. However, the lack of straightforward evidence for a necessity bias in our child results, together with its superfluity given our input results, suggests that a bias toward strong meanings is dispensable, even for modals.

5 General discussion and future directions

How do children figure out the force of their modals? In particular, what prevents them from falling prey to the subset problem modals give rise to and hypothesizing possibility meanings for necessity modals? To address these questions, we examined the modals that English-learning young children get exposed to and produce themselves. We found that children seem to master possibility modals early: by age 2, they are already using them productively, with and without negation, and in apparently adult-like ways. Children, however, seem to struggle with necessity modals. The few necessity modals they produce do not seem adult-like and appear in situations where adults prefer possibility modals. If this struggle with necessity modals persists into the preschool years, it could explain why prior studies show that children tend to accept them in possibility contexts (they’re uncertain about their force), and also why they accept possibility modals in necessity contexts (they lack a stronger alternative).

Yet children eventually figure out necessity modals, and the question is how. From our input study, we see that given the way modals are used in speech to children, children cannot reliably make use of DE environments like negation, as Gualmini and Schwarz (2009) proposed as a general solution for subset problems. Negation may even be partly responsible for children’s difficulties with necessity modals. First, its scopal behavior with modals is not uniform: some, but not all, necessity modals outscope negation. If children were to rely on negation to figure out the force of necessity modals, they could be misled into thinking that a modal like must expresses possibility (must not ∼ cannot), if they assume that negation scopes over the modal. Second, we found that negated necessity modals are rare in speech to children, perhaps for functional reasons, as speakers can express non-necessity via scalar implicatures triggered by the simple use of a possibility modal. Finally, Experiment 1 shows that the context is the least clear about force for negated necessity modals. This seems to be due to their use in impossibility situations, as ways to soften requests or orders (e.g., ‘you don’t have to break those things’, used as a prohibition). Negation, however, might be quite useful for children to home in early on possibility meanings for possibility modals: it occurs frequently with possibility modals, and our experimental results suggest that negated possibility contexts are particularly informative about the force of the modal.

If learners can’t rely on DE environments to solve the subset problem for modals, might they then need a necessity bias? Such a bias is in principle not necessary, as our experiments show that the conversational context in which modals are used is informative about force. What exactly about the context gives away modal force? Our initial foray into contextual features suggests one factor that could be particularly helpful for deontic modals is the perceived (un)desirability of the prejacent (e.g., ‘you have to eat your peas’ vs. ‘you can have a cookie’). Desirability is a notion that should uncontroversially be available to young children, though its association with obligations may take some time. Experiment 4 confirms the potential usefulness of desirability and shows that root necessity modals tend to occur with undesirable prejacents, and possibility modals with desirable prejacents. Participants are better at guessing necessity modals when they occur with undesirable prejacents. For epistemic modality, our post-hoc analysis suggests that contexts that explicitly highlight salient evidence in favor of the prejacent may bias interpretations toward necessity. Other aspects of the context could also prove useful, including situational cues (e.g., who the interlocutors are), cues from world knowledge (e.g., what is allowed or prohibited), or pragmatic cues (what the speaker is trying to achieve, in particular performing orders, permissions, or prohibitions). We plan to explore this further in future work.

Taken together, however, the results from our input study and our child study seem to lead to a conundrum: if the conversational context is informative for both forces (Experiments 2 and 3 suggest that context is particularly helpful for necessity modals), why should children struggle more with necessity modals? Several factors could be at play. First, these difficulties might be a matter of quantity, rather than quality, as our corpus results show that necessity modals are less common in the input.Footnote 35 Second, children may need to accrue some world knowledge to be able to make use of contextual cues (e.g., the association between obligations and undesirability). Children might also face conflicting cues. In particular, negative contexts seem useful for possibility modals, but misleading for some necessity modals. As discussed, if children assume the same scope relations for can and must, uses of mustn’t could suggest to them that it expresses possibility. And interestingly, when we compare our two affirmative root conditions, we found a lower performance for children’s must (42.6%) than for have to (60.2%), though this could reflect differences in their input frequency (have to represents 12% of all parents’ modal utterances, must only 2.3%). The interaction with negation could also explain why possibility modals are mastered so early: our study of the input shows that negated possibility modals are frequent and used in particularly informative contexts (e.g., to talk about prohibitions or physical impossibilities). Last, children’s struggles with necessity modals might not reflect a lack of knowledge of their underlying force, but rather difficulty deploying this knowledge in the right situations. Children may have trouble tracking what information is shared among interlocutors and thus grasping the intended domain of quantification (as has been argued for definite descriptions, where children seem to be overly permissive in using and accepting definites in contexts in which their uniqueness presupposition is not satisfied; Karmiloff-Smith 1979; Schaeffer and Matthewson 2005; Brockmann et al. 2018).

What we hope to have shown here is that the conversational context is a rich source of information for modal force, so that, in principle, learners can solve the subset problem without having to rely on potentially misleading negative contexts or on a controversial strong (necessity) bias. We have only begun to scratch the surface for which properties of the context are useful and why, but our results show that even the short, written snippets of conversation we provided to adult participants are informative, and this informativity is above and beyond the more limited context in the prejacent alone (Exp. 1 vs. Exps. 2/3). In fact, even just the information in the prejacent leads to above chance success in Experiment 2. Note that the context in real life is far richer than in Experiment 1 contexts, which lack prosodic and emotive information carried by speech, shared knowledge between mother and children, and visual information (among other information). Our studies, in combination with the fact that real life contexts are much richer, suggest that usage contexts may richly support modal force learning. That said, we don’t know yet how representative these contextually useful cases are in children’s actual experiences or if the additional factors (e.g., prosody) will be enriching, as seems intuitive, or obfuscating. Now that we are confident that information of some kind is available in the context and that desirability and mention of evidence are two promising types of information supporting modal meanings, we can pursue research asking whether children actually make use of these (and other) specific aspects of the context to acquire modal force.

Our child study shows no evidence for a necessity bias in children’s early modal productions. In fact, children’s early successes with possibility modals and failures with necessity modals could even suggest a bias toward possibility. Still, our results cannot rule out children actually having a necessity bias and grasping the force of necessity modals, but failing to use them in an adult-like way for independent reasons. In future work, we plan to test for such biases more directly through a novel modal word task, adapted from an adult study in Dieuleveut et al. (2021), to see what meanings children attribute to novel modals.

To address what aspects of the context are useful and whether children actually make use of them in their modal force acquisition, we plan on testing whether various features of the context in the input are good predictors of children’s mastery of necessity modals, as indexed by accuracy on the child HSP task. For instance, to see whether desirability actually matters in children’s (root) modal acquisition, we could test whether frequent uses of necessity modals with undesirable prejacents in the input predict earlier mastery of necessity modals: will a child whose parents primarily use necessity modals with undesirable prejacents use necessity modals in an adult-like way sooner than a child whose parents use necessity modals more often with desirable prejacents? (See Dieuleveut 2021 for preliminary results.Footnote 36)