Abstract

Key legislations in many countries emphasize the importance of involving children in decisions regarding their own health at a level commensurate with their age and capacities. Research is engaged in developing tools to assess capacity in children in order to facilitate their responsible involvement. These instruments, however, are usually based on the cognitive criteria for capacity assessment as defined by Appelbaum and Grisso and thus ill adapted to address the life-situation of children. The aim of this paper is to revisit and critically reflect upon the current definitions of decision-making capacity. For this purpose, we propose to see capacity through the lens of essential contestability as it warns us against any reification of what it means to have capacity. Currently, capacity is often perceived of as a mental or cognitive ability which somehow resides within the person, obscuring the fact that capacity is not just an objective property which can be assessed, but always operates within a dominant cultural framework that “creates” that same capacity and defines the threshold between capable and incapable in a specific situation. Defining capacity as an essentially contested concept means using it in a questioning mode and giving space to alternative interpretations that might inform and advance the debate surrounding decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

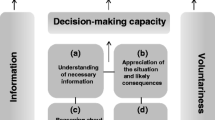

Informed consent is the key principle in both clinical and research settings (Dunn et al. 2006). To be valid and meaningful, consent needs to be provided voluntarily, knowingly and rationally (Mutcherson 2005). This is only possible if the patient has decision-making capacity to understand, appreciate, and use the disclosed information to make a consistent choice (Appelbaum 2007). Decisional capacity is the main criterion to transform such a choice into a legally binding decision of a competent person. Although, capacity and competence are often used interchangeably, the former is usually used for clinical assessments, whereas the latter is a legal construct that can only be determined in a court of law (Ganzini et al. 2004; Ruhe et al. 2016). Still, in the United Kingdom, they have inverted meanings: capacity carries legal connotations and competence clinical ones (Bielby 2005). In most jurisdictions, the chronological age of 18 is the threshold for a baseline presumption of competence unless there is a reason to suspect cognitive impairment (Appelbaum 2007; Mutcherson 2005). In the latter case, physicians need to strike an appropriate balance between protecting patients’ well-being and respecting their autonomy (Appelbaum 2007).

Challenges arise when we translate this framework for decision-making into pediatric healthcare (Friedman Ross 2016). Various factors complicate this process. Unlike adults, children as a class are usually considered incompetent with the underlying assumption that they also lack decisional capacity (Hein et al. 2015a; Mutcherson 2005). As a result, their parents need to make surrogate decisions in their best interest. This means that in the pediatric context, the traditional patient-physician relationship is no longer dyadic, but always mediated by a third party (Friedman Ross 2016; Gabe et al. 2004). To some degree, thus, «pediatrics turns bioethics on its head because the basic assumptions no longer hold» (Friedman Ross 2016, p. 272). This raises the question as to whether a capacity-based model closely linked to adult-centred notions such as autonomy and self-determination can promote children’s involement in decision-making and address their needs.

In this paper, we argue that it is crucial to re-think this traditional framework. For this purpose, we propose to see capacity through the lens of Gallie’s notion of essential contestability. We start by outlining the main ethical and practical issues regarding pediatric decision-making in research and clinical practice. We then critically assess research aimed at making an empirical contribution to the capacity debate by developing competence assement tools for children. In order to make a clear case for capacity as an essentially contested concept, in the next section we provide an overview of the prescribed seven criteria for such concepts. Our aim is not to further complicate an already delicate issue or to eliminate the possibility of capacity assessment. The goal is rather to safeguard the concept’s potential critical value against any standardized interpretation that risks excluding certain vulnerable groups from healthcare decision-making.

Decision-making in pediatrics: challenges and promises

Although children generally do not have legal competence, ethical guidelines increasingly emphasize the importance of involving children and adolescents in the healthcare decision-making process at a level that is appropriate for their development (Ruhe et al. 2015). This trend mirrors a change in the way children are conceptualized: from impaired adults who need to be prepared to enter society, to active beings who contribute and are already part of society (Matthews and Mullin 2015). While the inclusion of children is the recommended approach, adequate implementation of their participation within the medical setting remains difficult. Various conceptual, ethical and more practical barriers have been identified in the literature (Ruhe et al. 2015; Wangmo and De Clercq et al. 2016).

First, it is not always clear what ‘having decision-making capacity’ exactly means. Overall, there are two different paradigms of decision-making capacity. The procedural account, which is the mainstream approach, states that in order to avoid undue paternalism, capacity assessment should be evaluated based on the process (form) by which the decision is reached, irrespective of the appropriateness of the outcome (Banner 2013). This means that decision-making is viewed as a purely mental (cognitive and voluntative) ability dictated predominantly by the principles of rationality and logic (Dekkers 2001). The fact that decision-making capacity is theorized as a process of individual calculation has much to do with its close connection with the notions of autonomy and informed consent, which are inextricably bound up with a model that conceives persons as rational negotiators who are separate from their bodies. On this account, capacity is generally thought of as an internal matter, as an ability residing inside a person (Donnelly 2010).

There is a growing discontent with this cognitivist model of capacity (Berghmans et al. 2004) especially among feminist scholars (Mackenzie and Stoljer 2000; Mackenzie 2010) and those working on mental health related issues (from a hermeneutic or narrative perspective) (Berghmans et al. 2004; Mahr 2015). The former argue that this traditional approach fails to take into account the interdependence of the self and state that decision-making is always already influenced by social and political structures. The latter are concerned that a focus on cognition and rationality may lead to discrimination of persons with a mental illness as their diseases involve defects of cognitive and other mental processes. For this reason, both groups advocate for a fuller acknowledgement of so-called substantive or non-cognitive factors in the conception of capacity, such as beliefs, values, desires and emotions that influence the decision outcome (Hermann et al. 2016). Emotions, for example, can contribute to good decision-making since they can motivate people to re-examine the basis on which a decision was made (“the decision feels good or wrong”) (Charland 1998; Donnelly 2010). These authors emphasize further that decision-making capacity is a socially learned ability that is heavily influenced by the interactions with social others. Hence, attempts should be made to address impediments and enhance it through dialogue (Donnelly 2010; Ruhe et al. 2016).

Besides these conceptual problems, there are also various ethical concerns in the capacity debate that vary depending on the context. In the case of treatment, physicians need to walk on the tightrope between allowing children to take part in decision-making and burdening them with complex decisions (Harrison et al. 1997). Studies show that involving children in their health care makes them feel appreciated, less anxious and distressed and enhances their collaboration (Moore and Kirk 2010; Runeson et al. 2002). However, for some children being involved in certain decisions might be too demanding and scare them off (Coyne 2008). This tension leaves physicians with the uncertainty of how and when to promote child participation.

In the research setting, there has been a shift from protection to access (Friedman Ross 2004). Despite the risk of abuse in human experimentation, pediatric research is necessary to improve children’s health and reduce the overall mortality rate (Shirky 1968). However, the ethical acceptability of clinical research in pediatrics is still hotly disputed, as it seems to “use” children to advance generalizable knowledge (De Clercq et al. 2015). This is especially the case for non-beneficial research that has no direct relationship to the child’s health. This explains why international guidelines oblige researchers to seek the assent of capacitated children in addition to parental consent (“permission”) (Kodish 2003). There is no consensus, however, on when and how (and even why) this assent process should be undertaken (Sibley et al. 2016). Some scholars argue that while children’s agreement to participate in research should be rational and informed, this is not required for refusal, particularly not in the case of non-beneficial research. Distress-based objections should be sufficient (Waligora et al. 2016). Others state that a dual consent procedure is needed, in which children need to provide informed consent together with their parents (Hein et al. 2015c). Baines (2011) goes even a step further by rejecting the notion of assent altogether. He claims that competent children should be given the right for independent consent and that parents should consent for incompetent children. However, decisions surrounding participation in research are very complex and highly demanding. It is not always easy for children and parents to distinguish therapeutic benefits for the patient from the scientific objective to obtain new knowledge (de Vries et al. 2010). Potentially beneficial clinical research with children, in fact, is usually brought up together with discussions regarding diagnosis and treatment (de Vries et al. 2010). This integration not only promotes therapeutic misconception, but may also lead to conflicting interests for the physician who is both clinician and researcher (de Vries et al. 2010). Some scholars argue that too much focus on consent and assent distracts from what is really important in these situations: relationships of mutual trust among physcians, children and parents (Pinxten et al. 2008).

Next to ethical barriers, there are also several practical difficulties that form major obstacles to child participation in the medical setting. The involvement of pediatric patients can only be meaningful if they have the opportunity to form their opinion and are encouraged to do so. This is only possible if they have access to adequate information and are taken seriously (Miller 2003). The problem is that physicians often do not have a common approach, lack training on communicating with children and are under an enormous time pressure (Kilkelly and Donnelly 2006). These practical hurdles are further exacerbated by the fact that there is no consensus on when children should be involved. From a legal point of view, important differences exist between (and even within) countries regarding the age (12, 14 or 16) at which minors can make decisions regarding their health (Ruhe et al. 2015). Countries that do not establish age limits make it necessary for physicians to assess the decision-making capacity of each singular pediatric patient (Ruhe et al. 2015). Although validated tools exist to assess adults’ capacity in the field of health care, such as the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool (MacCAT), at present, no standardized methods are available in pediatrics.

Cognitive capacity and its hidden assumptions

The differing opinions on decision-making in pediatrics show how crucial the concept of capacity is in both the clinical and research setting. The ethical dispute at the bottom of these discussions is whether children can and should make important decisions regarding their health. Associated with the ‘can’ is a plethora of unanswered questions as to when these abilities arise and how they can be assessed.

According to Hein and colleagues (2015a), involvement of children in medical issues is hampered by the lack of empirical research on minors’ decision-making capacity. They claim that previous discussions on child consent have focused too much on normative (and legal) concerns and have neglected our limited knowledge about children’s capacity. In effect, since the landmark study of Weithorn and Campbell (1982), few empirical studies have concentrated on capacity assessment in pediatrics and all of them contain various methodological flaws (Hein et al. 2015a; Miller et al. 2003; Moore and Kirk 2010; Ruhe et al. 2015). To overcome this research gap, Hein and colleagues (2012, 2014) have developed an assessment instrument for children by modifying the MacCAT for clinical research for adults. They administered the tool (semi-structured interviews) to a group of 161 pediatric patients (age 6–18) eligible for clinical research trials at various pediatric departments (Hein et al. 2014, 2015b). The outcomes of the test were compared with expert (ethicists, psychologists and psychiatrists) judgments regarding the children’s capacity (reference standard). The study demonstrated that age is the key factor that explains variance in children’s capacity to consent and that other factors such as gender, disease experience, ethnicity, and socio-economic status have no direct impact on capacity. Based on these results, the research group has suggested a case-by-case capacity assessment for children from 10 to 12 and a double informed consent (rather than assent) procedure for children from the age of 12 (Hein et al. 2015c).

The efforts of this Dutch research group might represent a promising step towards a more structured and pragmatic assessment of capacity in pediatrics, especially within the research context. Their proposal to: (1) use a fixed age limit as a cut-off for capacity and consent and (2) limit individual evaluation to the group of children in which probability of competence is unclear, might impose a lower burden on patients and professionals than a general case-by-case assessment. These recommendations seem to imply a rejection of the assumption that minors as a class are incompetent. In other words, they seem to comply with the authors’ aim to facilitate the responsible involvement of children in clinical trials while doing justice to the capacities that children possess and the challenges they need to face (Hein et al. 2015c).

Although it is important to underpin the capacity debate with empirical research, we should keep in mind the theoretical assumptions that underly the development of these empirical tools and ask ourselves whether the determination of (in)-capacity by the MacCAT has empirical validity or whether it reveals something about the test and its underlying definition of capacity (Charland 2015). The MacCat is based on the cognitive criteria for capacity assessment as defined by Appelbaum and Grisso in their landmark paper of 1988. But, as Breden and Vollmann (2004) state, this «cognitive focus […] misses the complexity of the decision process in real life» and «is in itself a normative convention» as it is closely connected with the ideal of the autonomous and self-directed adult which places children a priori in a default position. Therefore, the question arises as to whether this tool can really do justice to children’s developing abilities. How can these studies challenge the adult-centric assumptions of legislative regulations if they rely on an instrument that is grounded in a framework that sees children as incomplete beings (Lansdown 2005; Peleg 2013)?

Further, we should not forget that the MacCAT was not developed as a stand-alone instrument for capacity assessment as it does not provide a clear cut-off separating capacity and incapacity. The tool still requires interpretation and thus a decision on the part of the physician who needs to take into account other factors such as the patient’s history and the type of decision (simple or complex) (Dunn et al. 2006). This also means that the MacCAT is not a neutral instrument, but always involves a subjective judgment that is influenced by personal values and social beliefs concerning childhood and capacity. That is not to deny that empirical research on child capacity is important to bridge the gap between ethical issues, policies and medical practice. Rather, we want to highlight the need to take a step back and to be aware of the social and cultural factors that influence our understanding of what it means to have capacity to guarantee that assessment practices are doing justice to the capacities that children possess (Munro 2013). Hence, it is vital to revisit the current, contending definitions of decision-making capacity. For this purpose, we propose to see capacity through the lens of essential contestability.

Identifying essentially contested concepts

Sixty years ago, the philosopher Walter Bryce Gallie introduced the notion of essentially contested concepts before a meeting of the Aristotelian Society. To illustrate his idea, he discussed the contestable nature of concepts such as art, social justice and democracy. Despite what this notion might suggest at first sight, Gallie (1956, 1964), was not primarily interested in the philosophical discussion on the nature of concepts, but rather in the way they are used and applied in debates within society (David-Hillel 2010). This may explain the increasing interest in this notion, especially in law and politics since the time of Gallie‘s first publication (Collier et al. 2006; Rodriguez 2015).

Gallie defined essentially contested concepts as «concepts the proper use of which inevitably involves endless disputes about their proper uses» which cannot be resolved using rational arguments (Gallie 1956). The term, however, has often been applied in an imprecise way to denote conceptual confusion or to refer to hotly disputed concepts (Collier et al. 2006; Waldron 2002). Yet, these latter problems are rather practical than fundamental: they are caused by the inconsistent use of terminology or disagreements and equivocation among different scholars and are thus, at least in principle, resolvable (by for example disambiguation). The essential contestability of concepts, however, does not consist in the intensity with which they are debated, but refers to their inherent potential to generate discussions that are somehow undecidable (Clarke 1979). Another way to understand Gallie’s idea is by relying on the distinction that Rawls (1971) and Dworkin (1972) make between concepts and conceptions; a distinction which is already implicitly present in Gallie’s own writing (Ruben 2010). A (core) concept like justice, for example, can have different competing conceptions or instantiations (justice as fairness, equality, equity, contract etc.) without there being an external criterion to single out any conception as the correct one (Lalumera 2014). For this reason, some scholars like Clarke (1979) have argued that it would be better to speak of essentially contestable rather than contested concepts. “Contestability” attributes the dispute to the concept itself, whereas “contested” seems to locate the source in the disagreement. A contestable concept is one that, at its core, contains a conflict of values (Clarke 1979).

Along with the definition, Gallie (1956) also provided several criteria for concepts to be essentially contestable. First, they need to be evaluative (“appraisive”), that is, they cannot just be descriptive, but have to express value judgments. Second, they are internally complex or cluster concepts that involve various dimensions. As a result—and this brings us to the third condition—they allow for a plurality of conflicting conceptions (van der Burg 2016). The fourth condition follows directly from the previous ones: essentially contested concepts must be open-ended and dynamic in character and must allow for different possible conceptions in the light of changing circumstances. Gallie stated that these are «the four most important necessary conditions to which any essentially contested concepts need to comply» (Gallie 1956). Still, he added three other (non-essential) criteria. Essentially contested concepts are interpreted differently by various users who apply them aggressively and defensively against other users’ conceptions. Next, these concepts are “exemplar”, this means that the different conceptions all somehow agree upon a fundamental idea or common minimum aspects (van der Burg 2016). Finally, the continuing debate surrounding essentially contested concepts leads to a better understanding and a fuller realization of these concepts.

A case for capacity as an essentially contested concept

In what follows, we want to show that the definition of essential contestability is applicable to the notion of capacity. It is important to emphasize that when we argue that capacity is an essentially contested concept, we are not alluding to the inconsistent use and/or conceptual confusion between “capacity” and “competence” both across the literature and in practice. Staying true to Gallie’s original idea, we are not interested in matters of conceptual blurriness that can be overcome with disambiguation. We are rather concerned with substantive disputes regarding a range of conceptions of capacity (in clinical assessment) which are all reasonable.

In order to demonstrate that capacity is an essentially contested concept, we need to assess whether it matches Gallie’s criteria (see Table 1).

Let us begin with the four salient conditions. Making a capacity assessment is never just a descriptive fact, but always also involves a normative judgment as it establishes whether persons should be allowed to make choices regarding their own health (criterion 1). Next, capacity contains multiple internal components such as procedures, choices, rational cognition, appraisal, individual and social or environmental factors (criterion 2). This internal complexity explains the various approaches to “capacity” depending on which of these components are emphasized (criterion 3). As we have seen, there are two main paradigms of decision-making capacity: the procedural-cognitivist model of capacity and the so-called substantive approach that focuses on beliefs, values, desires and emotions. Given these different “faces” of capacity, it seems reasonable to assert that capacity also fulfils the fourth criterion (IV) of openness. Moreover, specific conceptions may be challenged and adapted in the light of changing circumstances. For example, although the procedural account of capacity generally downplays external factors in the assessment of capacity (such as outcome), its advocates endorse the idea of a variable standard for capacity that requires greater levels of capacity for more risky and complex decisions (Collier et al. 2006; Donnelly 2010). The openness criterion is also manifest in the fact that the set of possible conceptions is not fixed, but may change over time. Not long ago, it was emphasized that “reasonableness” was a criterion of capacity, thus only a person making a “wise” choice was granted to turn that choice into a legally binding decisions (Roth et al. 1977). It is not unlikely that in the future due to the rise of cognitive enhancement technologies our conception of decision-making capacity will alter significantly. Also the remaining criteria of Gallie’s “essentially contested concept” seem to be fulfilled. Capacity is clearly used aggressively and defensively by various competitors (criterion V). Furthermore, notwithstanding the various interpretations, the various positions all seem to agree that capacity functions as a gatekeeper to autonomy (regardless of wether one interprets it in individualistic or more relational terms) and thus the exemplar criterion (VI) seems to match as well. Finally, although the disputes between the various approaches have not been fully “settled”, attempts have been made to emphasize the contribution that each can make to gain a better understanding of decision-making capacity (criterion VII). In what follows, we are mainly interested in the latter dimension that Gallie laid out.

Capacity as essentially contestable: a useful concept for decision-making in pediatrics?

It has been argued that many concepts would be valid candidates for essential contestability and for many notions (e.g. violence, security, medicine, dignity, rape, and rule of law), this argument has in fact been made (Rodriguez 2015). However, it is not enough to verify whether a concept meets the basic criteria of essential contestability, the question is whether it is also useful to view it through this lens (Ehrenberg 2011).

In this paper, we want to argue that the recognition of capacity as an essentially contested concept is valuable as it warns us against any reficiation of what it means to have capacity. Currently, capacity is often perceived of as a cognitive ability which somehow resides within the person, obscuring the fact that capacity is not just an objective property which can be assessed, but always operates within a dominant cultural framework that “creates” that same capacity. Defining capacity as an essentially contested concept means using it in a questionning mode and giving space to alternative interpretations that might enhance the debate surrounding decision-making.

We have seen that the rational and cognitivist approach to capacity is in a close relationship with the dominant (individualistic) understanding of autonomy, competence and informed consent within mainstream bioethics. In the health care context, respect for autonomy means that adults are granted the presumption of competence and are treated as if they possess the mental capacity to make decisions. However, this presumption is often set aside with regard to people who somehow deviate from the gold standard for competent decision-making (e.g. cognitively impaired elderly, mentally disabled persons and individuals suffering from mental illness) (Berghmans et al. 2004; Sjöstrand et al. 2015). Likewise, women are more at risk than men to have their capacity questioned due to stereotypical views of women as less rational and autonomous than men (Secker 1990). In other words, “vulnerable” groups are often unjustly deemed to lack the decisional capacity to make reasoned medical decisions because their illness, age or gender might have a negative effect on those cognitive abilities that are traditionally associated with decision-making capacity. This explains why alternative approaches to capacity have been developed which could do more justice to those patients considered being the “other” (Donnelly 2010). The development of these approaches is closely connected with the emergence of new (relational) contributions to standard bioethics in general. What is common to these alternative perspectives is that they start from the premise that traditional ways of doing bioethics are fundamentally value-laden and findings of (in)capacity thus inevitably socially constructed (Secker 1990). This means that capacity is no longer exclusively conceived as an intrinsic feature or an inherent property of persons which can be objectively assessed, but is rather considered to be determined (and shaped) by social factors which determine what counts as being capable (Secker 1990) (see Fig. 1). This also implies a shift away from assessing capacity towards a focus on how to enhance it by taking into account both personal and social factors that might impede or promote capacity (Donnelly 2010; Secker 1990).

A similar “revolution” is needed in pediatrics if we want to include children as partners in their medical care. Like people with mental impairments, children are still seen as the other to the norm since they are deemed to lack the cognitive abilities of “normal adults”. This explains why they are not granted the assumption of having decision-making capacity, but bear the burden of proof for capacity, placing them in a very demanding position (Ruhe et al. 2016). That is not to deny that children are still developing and lack certain cognitive and volitative capacities, but to highlight that children, maybe more than any other group in society, are emotionally, socially and financially dependent on their caregivers and their environment (Lansdown 2005). This means that their capacity might be hampered by parental attitudes (e.g. over-protection, control, low support for emotional and functional independence) and the physician’s experience, workload and values (e.g. lack of communication skills, lack of time etc.).

By understanding decisional capacity as an essentially contestable concept, we are able to question the cognitive standards by which children are assessed. That does not mean that we want to reject capacity assessment tools (like the MacCAT) as a useful addition to help physicians to make capacity assessments, but to remind that we should not be blind to its implicit normative standards and to the possible risk of neglecting social, cultural and biographical factors that which may influence children’s decision-making capacity. This could be done, for example, by considering the multiple narratives (patient, parents, physicians) present in a healthcare situation to evaluate what parents and professionals do to enhance children’s decision-making capacity (Bridgeman 2007). This means to shift the focus away from a deficit model of capacity (lack of personal property) to one of a common responsibility, where all parties involved in the decision-making process contribute to capacity (Ruhe et al. 2015, 2016).

Conclusion

Although the discussion between the various approaches to capacity (and bioethics in general) is still ongoing, there is a growing awareness of the need to embrace this diversity and not to remain locked in one perspective (Jennings 2016). At the same time, efforts are made to render capacity ‘measurable’. In this paper, we have argued that the latter project does not solve the on-going capacity debate. That does not mean, however, that we promote a kind of conceptual relativism or that we deny the importance of the assessment of a patient’s decisional capacity within a treatment or research context. However, we think it is dangerous to treat these assessment practices as objective tools and to overlook that they are informed by prevailing societal ideals of rationality and individualism. The standards for capacity cannot be discovered—as if capacity is a simple matter of fact—but always need to be chosen (Buchanan and Brock 1989). In other words, it is not sufficient to have policies that sustain child participation; in addition, we need to broaden the very meaning of it if we want to respect and do justice to the capacities that children possess. In this paper, we have argued that a good way to do this is to treat capacity as an essentially contested concept. This means we consider the on-going debate around the notion of capacity as inherently valuable rather than a weakness that needs to be overcome.

References

Appelbaum, P.S. 1988. Assessing Patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. New England Journal of Medicine 319 (25): 1635–1638.

Appelbaum, P.S. 2007. Assessment of patients’ competence to con-sent to treatment. New England Journal of Medicine 357: 1834–1840.

Baines, P. 2011. Assent for children’s participation in research is incoherent and wrong. Archives of Disease in Childhood 96 (10): 960–962.

Banner, N.F. 2013. Can procedural and substantive elements of decision-making be reconciled in assessments of mental capacity. International Journal of Law in Context 9 (1): 71–86.

Berghmans, R., D., Dickenson, and R., Ter Meulen. 2004. Mental capacity: In search of alternative perspectives. Health Care Analysis 12 (4): 251–263.

Bielby, P. 2005. The conflation of competence and capacity in English medical law: A philosophical critique. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 8 (3): 357–369.

Breden, T.M., and J., Vollmann.. 2004. The cognitive based approach of capacity assessment in psychiatry. A philosophical critique of the MacCAT-T. Health Care Analysis 12 (4): 273–283.

Bridgeman, J. 2007. Parental responsibility, young children and healthcare Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buchanan, A. E., and D.W., Brock. 1989. Deciding for others: The ethics of surrogate decision making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Charland, L.C. 1998. Is Mr Spock mentally competent? Competence to consent and emotion. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology 5 (1): 67–81.

Charland, L.C. 2015. Decision-making capacity. The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Fall 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2015/entries/decision-capacity/>.

Clarke, B. 1979. Eccentrically contested concepts. British Journal of Political Science 9: 122–126.

Collier, D., F.D., Hidalgo, and A.O., Maciuceanu. 2006. Essentially contested concepts: Debates and applications. Journal of Political Ideologies 11 (3): 211–246.

Coyne, I. 2008. Children’s participation in consultations and decision-making at health service level: A review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (11): 1682–1689.

David-Hillel, R., and W.B., Gallie. 2010. Essentially Contested Concepts. Philosophical Papers 39 (2): 257–270.

De Clercq, E., D.O, Badarau, K.M., Ruhe, and T., Wangmo. 2015. Body matters: Rethinking the ethical acceptability of non-beneficial clinical research with children. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 18 (3):421–431.

de Vries, M. C., J.W., Wit, D.P., Engberts, G.J., Kaspers, and E. van Leeuwen, 2010. Norms versus practice: Pediatric oncologists’ attitudes towards involving adolescents in decision-making concerning research participation. Pediatric Blood and Cancer 55 (1): 123–128.

de Vries, M. C., M., Houtlosser, J.W., Wit, D.P., Engberts, D., Bresters, G.J., Kaspers, and E., van Leeuwen. 2011. Ethical issues at the interface of clinical care and research practice in pediatric oncology: A narrative review of parents’ and physicians’ experiences. BMC Medical Ethics. doi:10.1186/1472-6939-12-18.

Dekkers, W.J.M. 2001. Autonomy and dependence: Chronic physical illness and decision-making capacity. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 4 (2): 185–192.

Donnelly, M. 2010. Healthcare decision-making and the law. Autonomy, capacity and the limits of liberalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dunn, L., M., Nowrangi, B., Palmer, D., Jeste, and E. Saks. 2006. Assessing decisional capacity for clinical research or treatment: A review of instruments. American Journal of Psychiatry 163: 1323–1334.

Dworkin, R. 1972. The Jurisprudence of Richard Nixon. The New York Review of Books 18 (8): 27–35.

Ehrenberg, K.M. 2011. Law is not (best considered) an essentially contested concept. Journal of Law in Context 7 (2): 209–232.

Gabe, J., G., Olumide, and M. Bury. 2004. 'It takes three to tango': A framework for understanding patient partnership in paediatric clinics. Social Science & Medicine 59: 1071.

Gallie, W.B. 1956. Essentially contested concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, New Series 56: 167–198.

Gallie, W.B. (1964) Philosophy and the Historical Understanding. London: Chatto and Windus.

Ganzini, L., L., Volicer, W.A., Nelson, E., Fox, and A.R. Derse, 2004. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 5 (4): 263–267.

Harrison, C., N.P., Kenny, M., Sidarous, and M., Rowell, 1997. Bioethics for clinicians: 9. Involving children in medical decisions. Canadian Medical Association Journal 156 (6): 825–828.

Hein, I., P., Troost, R., Lindeboom, M., de Vries, C., Zwaan, and R., Lindauer, 2012. Assessing children’s competence to consent in research by a standardized tool: A validity study. BMC Pediatrics 12: 156–163.

Hein, I., P., Troost, R., Lindeboom, M.A., Benninga, C.M., Zwaan, J.B., Van Goudoever, and R.J. Lindauer, 2014. Accuracy of the macarthur competence assessment tool for clinical research (MacCAT-CR) for measuring children’s competence to consent to clinical research. JAMA Pediatr 168 (12): 1147–1153.

Hein, I. M., P.W., Troost, A., Broersma, M.C., de Vries, J.G., Daams, and R.J., Lindauer, 2015a. Why is it hard to make progress in assessing children’s decision-making competence? BMC Medical Ethics. doi:10.1186/1472-6939-16-1.

Hein, I.M., P.W., Troost, R., Lindeboom, M.A., Benninga, C.M., Zwaan, J.B., Van Goudoever, and R.J. Lindauer, 2015b. Key factors in children’s competence to consent to clinical research. BMC Medical Ethics. doi:10.1186/s12910-015-0066-0.

Hein, I. M., M.C., de Vries, P.W., Troost, G., Meynen, J.B., Van Goudoever, and R.J., Lindauer. 2015c. Informed consent instead of assent is appropriate in children from the age of twelve: Policy implications of new findings on children’s competence to consent to clinical research. BMC Medical Ethics. doi:10.1186/s12910-015-0067-2.

Hermann, H., 2016. Emotion and value in the evaluation of medical decision-making capacity: A narrative review of arguments. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 765.

Jennings, B. 2016. Reconceptualizing autonomy: A relational turn. Hastings Center Report 46 (3):11–16.

Kilkelly, U., and M., Donnelly. 2006. The child’s right to be heard in the health care setting. Perspectives of children, parents and health professionals. Office of the Minister for Children. http://www.dcya.gov.ie/documents/research/The_Childs_Right_to_be_Heard_in_the_Healthcare_Setting.pdf. Assessed 17 May 2016.

Kodish, E. 2003. Informed consent for pediatric research: Is it really possible? The Journal of Pediatrics 42 (2): 89–90.

Lalumera, E. 2014. On the explanatory value of the concept-conception distinction. Rivista Italiana di Filosofia del Linguaggio 8 (3): 73–81.

Lansdown, G. 2005. The evolving capacities of the child. Sienna: UNICEF.

Mackenzie, C. 2010. Conceptions of the body and conceptions of autonomy in Bioethics. In Feminist Bioethics: At the Center, On the Margins, eds. J. L. Scully, L. Baldwin-Ragaven, and P. Fitzpatrick, 71–90. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mackenzie, C., and N., Stoljar. 2000. Relational autonomy. Feminist perspectives on autonomy, agency and the social self. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mahr, G. 2015. Narrative Medicine and decision-making capacity. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 21: 503–507.

Matthews, G., and A., Mullin 2015. The Philosophy of Childhood. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed 12 July 2016. Retrieved from: http://www.plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2015/entries/childhood/.

Miller, J. 2003. Never Too Young: How young children can take responsibility and make decisions. London: Save the Children Fund.

Moore, L., and S., Kirk. 2010. A Literature review of children’s and young people’s participation in decisions relating to health care. Journal of Clinical Nursing 19: 2215–2225.

Munro, N. 2013. The social construction of decision-making capacity. Mental Health and Mental Capacity Law. https://mentalhealthandcapacitylaw.wordpress.com/author/llzpm/.

Mutcherson, K.M. 2005. whose body is it anyway—an updated model of healthcare decision-making rights for adolescents. Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy 14 (2): 251–325.

Peleg, N. 2013. Reconceptualising the child’s right to development: children and the capability approach. s Rights 21: 523–542.

Pinxten, W., H., Nys, and K., Dierickx. 2008. Regulating trust in pediatric clinical trials. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 11 (4): 439–444.

Rawls, J. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rodriguez, P.A. 2015. Human dignity as an essentially contested concept. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 28 (4): 743–756.

Ross, L.F. 2004. Children in medical research: Balancing protection and access: Has the pendulum swung too far? Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 47 (4): 519–536.

Ross, L.F. 2016. Theory and practice of pediatric bioethics. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 58 (3): 267–280.

Roth, L., A., Meisel, and C., Lidz, 1977. Tests of competency to consent to treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry 134: 279–284.

Ruben, D.H., and W.B., Gallie. 2010. Essentially contested concepts. Philosophical Papers 39 (2): 257–270. and .

Ruhe, K., T., Wangmo, D.O., Badarau, B.E., Elger, and F., Niggli. 2015. Decision-making capacity of children and adolescents—suggestions for advancing the concept’s implementation in pediatric healthcare. European Journal of Pediatrics 174: 775–782.

Ruhe, K., E., De Clercq, T., Wangmo, and B.S. Elger. 2016. Relational capacity: Broadening the notion of decision-making capacity in paediatric healthcare. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. doi:10.1007/s11673-016-9735-z.

Runeson, I., I., Hallström, G., Elander, and G. Hermerén. 2002. Children’s participation in the decision-making process during hospitalization: An observational study. Nursing Ethics 9 (6): 583–598.

Secker, B. 1990. Labelling patient (in)competence: A feminist analysis of medico-legal discourse. Journal of Social Philosophy 30 (2): 295–314.

Shirkey, H. 1968. Therapeutic orphans. Journal of Pediatrics 72 (1): 119–120.

Sibley, A., A.J., Pollard, R., Fitzpatrick, and M., Sheehan. 2016. Developing a new justification for assent. BMC Medical Ethics. doi:10.1186/s12910-015-0085-x.

Sjöstrand, M., K., Petter, L., Sandman, G., Helgesson, S., Eriksson, and N., Juth. 2015. Conceptions of decision-making capacity in psychiatry: interviews with Swedish psychiatrists. BMC Medical Ethics: 16–34.

van der Burg, W. 2016. Law as a second-order essentially contested concept. Erasmus Working Paper Series on Jurisprudence and Socio-Legal Studies 16. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2783292.

Waldron, J. 2002. Is the rule of law an essentially contested concept (in Florida)? Law and Philosophy 21 (2): 137–164.

Waligora, M., J., Rózyńska, and J., Piasecki. 2016. Child’s objection to non-beneficial research: capacity and distress based models. Medicine Health Care and Philosophy 19: 65–70.

Wangmo, T., E., De Clercq, K., Ruhe, M., Beck-Popovic, J., Rischewski, R., Angst, M., Ansari and B.S., Elger. (2016). Better to know than to imagine: Including children in their health care. The American Journal of Bioethics. doi:10.1080/23294515.2016.1207724.

Weithorn, L.A., and S.B., Campbell. 1982. The competency of children and adolescents to make informed treatment decisions. Early Adolescence 53 (6): 1589–1598.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the Käthe-Zingg-Schwichtenberg-Fonds (Schweizerische Akademie der Medizinischen Wissenschaften—SAMW) and by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF NRP-67 Grant Number 406740 139283/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Clercq, E., Ruhe, K., Rost, M. et al. Is decision-making capacity an “essentially contested” concept in pediatrics?. Med Health Care and Philos 20, 425–433 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-017-9768-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-017-9768-z