Abstract

Problems arise when applying the current procedural conceptualization of decision-making capacity to paediatric healthcare: Its emphasis on content-neutrality and rational cognition as well as its implicit assumption that capacity is an ability that resides within a person jeopardizes children’s position in decision-making. The purpose of the paper is to challenge this dominant account of capacity and provide an alternative for how capacity should be understood in paediatric care. First, the influence of developmental psychologist Jean Piaget upon the notion of capacity is discussed, followed by an examination of Vygostky’s contextualist view on children’s development, which emphasizes social interactions and learning for decision-making capacity. In drawing parallels between autonomy and capacity, substantive approaches to relational autonomy are presented that underline the importance of the content of a decision. The authors then provide a relational reconceptualization of capacity that leads the focus away from the individual to include important social others such as parents and physicians. Within this new approach, the outcome of adults’ decision-making processes is accepted as a guiding factor for a good decision for the child. If the child makes a choice that is not approved by adults, the new conceptualization emphasizes mutual exchange and engagement by both parties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Leila is thirteen years old. She was diagnosed with osteosarcoma in the right leg four years ago. Initial treatment proved to be difficult, and after a relapse her leg was amputated. For a period of six months, she was considered in remission. During her last check-up, multiple metastases appeared. Leila’s oncologist and parents wished to immediately start chemotherapy. However, Leila refused and became very upset whenever the issue of starting chemotherapy was discussed. She said that nobody listened to her and that she had enough. She would not risk having her other leg “chopped off.” Her parents did not know how to respond to her unwillingness to receive treatment and got easily irritated during these discussions. Leila’s oncologist was not convinced that she should be allowed to make the decision because she thought Leila was too emotional and could not fully grasp the severity of the situation. However, the oncologist also realized that Leila had so far been very involved in all aspects of her illness and had a detailed understanding of her condition.Footnote 1

Decision-making capacity denotes a person’s ability to make choices. In healthcare ethics and law, capacity is closely linked to the concepts of autonomy and competence. Autonomy is the right of patients to make informed choices regarding their care (Beauchamp and Childress 2001). Although competence is often used interchangeably with capacity, it usually denotes a legal determination of a patient’s ability made by a court of law, whereas capacity is used to refer to a clinical assessment (Ganzini et al. 2004). Still, depending on the jurisdiction, the meaning of the terms can switch (Charland 2011). In this paper, our emphasis is on decisional capacity as a clinical finding that acts as a gatekeeper to patient autonomy.

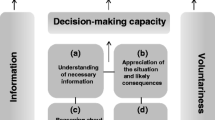

To avoid the risk of medical paternalism, accounts of capacity (and autonomy) are mainly procedural. This means that healthcare professionals only judge the process by which a decision is reached and not its content (Mackenzie and Rogers 2013). To be deemed as someone possessing capacity, a patient must be able to (a) communicate a decision, (b) understand relevant information, (c) appreciate the situation and likely consequences, and (d) reason about treatment options (Mackenzie and Rogers 2013; Appelbaum 2007; Lo 1990). Whenever these procedural criteria are fulfilled, a patient is free to decide for him/herself, irrespective of the apparent irrationality of the decisional outcome (e.g., avoidable death). In addition, capacity is believed to be decision relative (Etchells et al. 1996). This means that capacity can vary within one and the same subject: a patient may have the capacity to make minor decisions (e.g., when to take medicine) but not major ones (e.g., if to take medicine) (Beauchamp and Childress 2001). It is important to keep in mind that establishing (in)capacity is not just a descriptive fact but often involves a normative dimension. That is, it includes a judgement of whether persons ought to make a decision or whether their choices should be overridden on moral grounds (Beauchamp and Childress 2001).

Several difficulties arise when a procedural account of capacity is applied to paediatrics. First, the criteria for capacity are governed by the ideal of cognitive rationality (Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000). The emphasis on cognitive functions demarcates children ipso facto as incapable since they are perceived to lack full cognitive complexity (Alderson and Montgomery 1996; Alderson 1992). Implicit in this is a conception of capacity as being a status. Thus, adult patients are assumed to have capacity (and thereby autonomy), whereas children are believed to gradually gain capacity as they mature. Due to this assumption, in adult patient care the burden of proof is on the physician: in order to restrict or deny a person’s autonomous choice, they need to ascertain that the person lacks capacity (Beauchamp and Childress 2001). In paediatrics, by contrast, children must demonstrate their ability to fulfil the aforementioned criteria of capacity (Alderson 2003; Dittmann 2008; Peter 2008). This requirement puts them in a challenging position with regard to gaining access to decision-making. Moreover, the process to establish capacity is also very time consuming and requires physicians to possess the necessary skills to assess capacity (Ruhe et al. 2014).

Second, the criteria implicitly assume that capacity is an attribute that resides within an individual. The procedural account of capacity is thus highly individualistic and does not account for the roles that social others like parents, siblings, nurses, or teachers play in helping children to learn and master the abilities necessary for capacity (Alderson 1992). When children are ill, they start out as “novices” with a limited understanding of issues concerning their health. Through time, experience, and teaching they grow increasingly familiar with various aspects surrounding their illness and its treatment. Some may become surprisingly well-informed and skilled “experts” of their condition (Alderson, Sutcliffe, and Curtis 2006). These changes are not only the result of mere exposure to hospitals and medical staff but emerge from careful interactions between the novice patient and others that provide information, answer questions, and help make sense of the illness experience (Holaday, Lamontagne, and Marciel 1994). Such contextual influences are neglected in the discussion surrounding children’s capacity (Alderson 1992, 2007).

Third, clinical reality is often not synchronized with the content-neutrality of the procedural approach to capacity. Children who are considered capacitated are usually granted the right to consent to treatment but not the right of refusal, especially when treatment is clearly curative (Freeman 2005). The child’s disagreement is then seen as “immature folly” (Alderson 1992, 120). This may explain why capacity only becomes an issue when children disagree (Alderson 1992). In the case of compliant decisions, there is no practical gain from taking measures to ascertain their ability to make such decisions. Hence, capacity assessment is not only inherently content-laden but also seems to have a tendency for paternalistic interference when capacitated children make choices that are perceived as diverging from their best interest. This raises the question of whether and to what extent content or so-called substantive aspects of decision-making can legitimately be integrated in capacity assessment (Banner 2013).

Legislation across the world acknowledges that the (clinical) capacity to make medical decisions does not suddenly appear when a person reaches the age of majority (i.e., is competent) and grants (legal) decision-making rights to those children who demonstrate sufficient capacity (e.g., the mature minor doctrine in the United States [Hickey 2007] or “Gillick competence”Footnote 2 in the United Kingdom [Larcher and Hutchinson 2010]). However, in order to further strengthen children’s role in healthcare, we believe there is a need for a new notion of capacity. The aim of this paper is to provide such a reconceptualization of capacity, one that better matches up with clinical practice and paediatric care. For this purpose, we critically discuss Piaget’s psychological theory of development, which emphasizes a rational and individualistic perception of children’s abilities. We then broaden the understanding of how abilities are learned by turning to the contextualist theory of Vygostky. We move forward by drawing on feminist theory to show that a combined process and content account of capacity provides a more accurate perspective of the situation of children as patients. Such an approach also emphasizes the responsibility of social others in children’s exercising of capacity. Finally, we explore how a relational conceptualisation of decision-making capacity can provide guidance in situations of conflict in the paediatric setting.

Capacity and Developmental Theory

“Inside–Out”— Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Theories of child development aim at describing and explaining changes that occur over time in areas such as cognition or language by identifying general principles that underlie these developments (Miller 1993). It seems natural to turn to these theories when inquiring about children’s ability to make decisions. Early bioethical, legal, and psychosocial literature on children’s ability to consent to treatment was influenced by Piaget’s theory of child development (Grisso and Vierling 1978; Stier 1978; Sametz 1979; Morrison, Morrison, and Holdridge-Crane 1979; Melton 1983). A cornerstone of his theory is the claim that children go through a series of discrete, invariable, and universal cognitive stages. Each stage is marked by several qualitative changes in children’s thinking and reasoning (Miller 1993). Piaget closely linked these stages to age and argued that at the age of fourteen children usually have the same information processing abilities as adults (Piaget 1972). However, Piaget’s theory has been widely criticized for several problematic assumptions and the flawed methodology of his experiments (Siegel and Hodkin 1982; Brainerd 1978). One main problem is that he underestimated children’s skills because he relied heavily on language to examine thought processes. Another critique is that Piaget was not interested in children’s ability to understand something after being taught but was solely concerned with studying what they already know and can or cannot perform on their own (Siegel 1993). However, a child’s failure to solve a problem may not reflect ignorance but a mere lack of teaching. An environment that adapts to children’s understanding can reveal surprising skills that otherwise would remain hidden (Siegel and Hodkin 1982). Practice and learning are thus crucial components of children’s performance (Inhelder, Sinclair, and Bovet 1974). Additionally, Piaget underestimates the importance of social others on children’s thought processes and behaviour (Siegel and Hodkin 1982). Overall, Piaget’s theory conceptualizes development as a rational process that is primarily driven by the child, who almost seems to be a subject separate from the social and physical environment (Murray 1983; Miller 1993). Anchoring the cognitive abilities necessary for decision-making capacity in Piagetian theory compels one to focus on the individual child and the demonstration of rational skills with little concern for context and learning. However, as the criticisms of Piaget’s theory show, children’s abilities may have been underestimated and contextual factors can have tremendous effects on performance. By seeing capacity (e.g., the ability to appreciate information related to diagnosis) as something that children “perform,” we seem to disregard that capacity is not something that simply “appears” but something that develops through communication, explanation, and interaction with others. If the criticisms of Piaget had found an echo in bioethics, then today’s conceptualization of capacity might have accounted more for environmental influences and have been less centred on the individual and cognition. Some scholars explicitly state that capacity requires a set of values (Buchanan and Brock 1989) and emotions that have a crucial role in decision-making capacity (Charland 1998). By defining capacity as a purely mental ability, this element is downplayed (Charland 2011). In the following, we will turn to Lev Vygotsky and present his theory of development, which focuses on context and social relationships, to gain a different understanding of capacity.

“Outside–In”—Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development

Vygostky’s theory can be placed under the umbrella of contextualist developmental theories, which emphasize the importance of socio-cultural environment for development. The child and her contextual environment are not seen as two separate entities but rather merge into each other (Miller 1993). Bronfenbrenner (1979) defines context as a system of interlinked settings that reach from the micro level (all settings—such as family or school—in which the child directly interacts) to the macro level (cultural context, e.g., norms, values, traditions). According to Vygotsky, all higher cognitive functions (e.g., thinking, memory, consciousness) have their origin in social cooperation and are generated by an initial exchange between the child and adults or peers (inter-mental) which then is internalized in order to become an individual function (intra-mental) (Miller 1993; Miller 2011; Vygotsky 1978b). A central idea of Vygostky’s theory is the “zone of proximal development,” which he conceptualizes as the distance between what a child can already do on her own and what she can achieve with the assistance of skilled adults or peers (Miller 1993; Vygotsky 1978a). A collaboration between a competent and a not yet competent individual leads to a joint completion of a task and the acquisition of necessary skills in the latter (Chaiklin 2003; Vygotsky 1978a). Vygotsky was thus more concerned with what children are able to achieve in collaboration than with what they are capable of doing alone at a given moment in time. He was more interested in the process of change than in what children had already achieved (Miller 1993; Vygotsky 1986; Holaday, Lamontagne, and Marciel 1994). Contrary to Piaget, Vygostky investigated how children were able to use certain “cues” intended to help them solve a problem rather than eliciting only an answer (Miller 1993). Rogoff and colleagues (1993) extended the zone of proximal development using the concept of “guided participation” to include forms of cultural learning other than higher cognitive functions. They emphasize the importance of verbal and non-verbal communication and children’s active participation as well as observation in everyday situations. Guided participation is realized through children’s collaboration in various activities with adults while structuring their role and responsibility via continuing communication. In the context of healthcare, the importance of such scaffolding is emphasized by Holaday and colleagues (1994), who argue that through structuring and support nurses can help children with diabetes in acquiring necessary knowledge as well as behaviours (e.g., giving shots). In this framework, the extent of children’s participation and the amount of support needed can be evaluated and should inform each other; that is, when a child has reached a level of control and has internalized a skill, outside help is no longer necessary and can even be irritating.

Vygotsky and other contextualist scholars provided a different perspective to Piaget on child development and the origin of skills. However, differences between them may be less irreconcilable than is often postulated, and both views together may actually provide for an interesting account of the diversity of children’s development (Tryphon and Vonèche 2013). The most obvious distinction between the two regards their analysis of the direction of development, often summarized as “inside–out” (Piaget) versus “outside–in” (Vygotsky) (Marti 1996, 58). By conceptualizing skills as originating from interaction, Vygotsky shifted the emphasis from the individual level to the social context. If we transpose this to the notion of capacity, we should no longer ask whether children fulfil all the required criteria but rather if they have the potential for learning certain cognitive and emotional skills and what others (e.g., parents, healthcare professionals) can do to assist in the acquisition of these skills. An assessment of capacity from a Vygotskyan perspective would thus always comprise questions about the context and the “cues” given to a child in order to make a decision in collaboration with others.

A Relational Dimension of Capacity—Revisiting a Feminist Critique of the Concept of Autonomy

We now turn to a feminist critique of the concept of autonomy, a critique that aims to further challenge the rationalistic and individualistic conceptualization of capacity and to develop an alternative approach. Autonomy is the ability to act upon one’s own authentic values, desires, and motives (Christman 2003). Autonomy is often criticized in feminist bioethics for promoting hyper-individualism, independence, and liberalism while perceiving relatedness and cooperation as threats to the self-determination of individuals (Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000). Feminist scholars, however, rarely ever completely discard the notion of autonomy; instead, they argue in favour of maintaining the concept of autonomy while rejecting its individualistic conceptualization. They develop a reconceptualization that reflects the embeddedness and interdependence of the self in social structures while preserving the original idea of individual agency (Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000). These relational views not only emphasize that agents’ values and commitments are shaped by social relationships and political and social environments but are also based on the claim that they influence the development and exercise of autonomy (Mackenzie 2008; Held 2007, 1993). The ethics of care approach reflects a similar focus on the connectedness of individuals with others and the importance of those relationships for moral agency (Gilligan 1982; Peter and Liaschenko 2013). Relational autonomy is identified as an umbrella term uniting theories “sharing the conviction that persons are socially embedded and that agents’ identities are formed within the context of social relationships” (Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000, 4).

Theories of autonomy can be separated into procedural and substantive accounts (Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000; Christman 2003; Stoljar 2013). Procedural theories are neutral with respect to the kind of actions that people undertake. What matters for labelling someone autonomous is that the person making a choice has undergone an internal process of appropriate critical reflection; that is, her actions are rooted in and consistent with her values, overall commitments, and objectives irrespective of their content. This means that persons living under oppressive circumstances can be autonomous as long as their decision-making results from a critical-thinking process (Christman 2004). The procedural account is often used to prevent paternalistic interference (e.g., the practice of veiling). However, procedural theories have been criticized for neglecting the consequences of internalized oppression for a person’s attitudes, values, and motives and their ability to critically reflect upon them (Stoljar 2013). By contrast, substantive theories address the issue of how oppressive modes of socialization can severely impair autonomous choice in that they attribute importance to the content of preferences or values that agents can form or act upon. Substantive theories are further divided into strong and weak approaches. Strong substantive accounts place restrictions on specific kinds of preferences compatible with autonomy. Within such an approach, choosing a life of subservience would not qualify as autonomous because the very content of the decision violates the normative constraints that are set with regard to autonomy, irrespective of the way the decision was formed (Stoljar 2013). However, strong substantive accounts have been charged with imposing certain values (e.g., equality) regardless of whether an individual embraces these values or not (Mackenzie 2008). In order to avoid this, weak substantive approaches do not directly constrain the types of action an agent can perform but place emphasis on the agent’s attitudes toward herself. In a weak substantive approach, a person is autonomous if her choice satisfies values such as self-respect or self-trust (Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000; Stoljar 2013).

Attempting a middle way between procedural and strong substantive accounts of autonomy, Mackenzie develops a weak substantive approach based on the belief that normative authority is grounded in certain attitudes towards oneself (2008). According to her, the value of self-respect is a central aspect of autonomous choice. If an individual lacks the conception that she is the “legitimate source of reasons for acting” (Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000, 525), her autonomy is impaired, in the sense that she does not acknowledge herself as meriting normative authority over her life. Mackenzie (2008) links relationships and social structures to the development of a sense of self. A failure of others to recognize an individual can lead to severe impairment of autonomy because a person may think that she is not worthy of deciding for herself and making claims to govern her life. Hence, the personal traits necessary to feel entitled to claim authority over one’s choices can only be developed interpersonally, through meaningful relationships. A person’s sense of self-respect that has previously been impaired by dysfunctional relationships can be developed and reconstructed if she has a network of social others that nurture her sense of self.

Within this approach, respect for autonomy means promoting conditions that are necessary to develop, maintain, and exercise normative authority over one’s own life (Mackenzie 2008). According to Mackenzie, respecting a person’s autonomy involves several obligations. To begin with, her point of view should be acknowledged and understood. This obligation is grounded in epistemic humility—recognizing that a person’s experiences are fundamentally subjective and shaped by how she perceives the situation in light of her values and commitments. However, respecting a person’s views should not prevent one from seeing when autonomy is impaired—for example, by negative attitudes towards oneself. Since such attitudes are shaped by interpersonal relationships, there is an obligation of social others to try to help redirect and re-evaluate certain convictions. Consequently, respect for autonomy involves respect for a person’s point of view while also supporting her in revising her attitudes towards herself. Mackenzie acknowledges that this view is committed to a kind of moral perfectionism in that it claims that certain choices are irreconcilable with a “good, valuable and flourishing life” (Mackenzie 2008, 529). Although Mackenzie does not make this explicit, her approach is based on the assumption that autonomy is not only a negative right—in that patients who are autonomous cannot be forced to accept treatment—but a positive right that entails others to help patients to be autonomous (Sjöstrand et al. 2013).

Just as one can approach autonomy with a weak substantive conceptualization, the same can be done with capacity. First, similar to self-respect, capacity can be understood as originating from social interactions and relationships. Consequently, social others can play a significant role in hampering or enhancing capacity. Second, although decision-making capacity is deemed to be content independent, this seems problematic in paediatric healthcare. As described earlier, children are not often granted choices that differ from what adults think is best. Hence, a procedural account of capacity falls short because it does not recognize the fact that adults have a conception of what is a good decision for the child. This tension could be addressed by acknowledging that certain normative expectations exist with regard to the outcome of children’s decision-making process, namely in the form of the decision that was reached by their parents and/or physicians. However, making adult’s decisions absolutely normative for children would defy the very purpose of capacity as a gatekeeper to autonomy. In assuming that adults usually aim at making decisions in light of what they think is the best outcome for the child, we propose a weak substantive approach to capacity. By doing so, the content of the child’s decision is a criterion for capacity and the decision of adults involved in the care is adopted as an orientation for a good outcome of the decision-making process. Discrepancy between the choices made by the child and adults indicates that both parties need to engage in exchanging their respective views.

Relational Capacity—Making the Concept More Applicable to Paediatric Care

As discussed, the current procedural account of capacity creates several problems when applied in a paediatric context. Furthermore, it fails to provide guidance as to how conflict can be solved because it leads to either questioning the child’s capacity or accepting their capacity while rejecting their entitlement to make the decision. By drawing from both Vygotsky and Mackenzie, we adopt a weak constitutive approach to capacity within which not only the thinking process but also the content of the decision is relevant to the assessment. The advice of parents and/or physicians is taken as a guiding example for a good decision. This means that when a child reaches a decision that is considered unwise by adults, it is acceptable to question the child’s decision-making capacity, but instead of excluding her from making a choice, it should be an incentive to promote her decision-making abilities. According to Vygotsky’s zone of proximal learning, this could be done by closely engaging with the child in decision-making and helping her identify certain aspects that adults think are crucial. At the same time, it must be acknowledged that all parties have their own perspectives which are grounded in certain attitudes and motives. This requires adults to also critically reflect upon their decision and be able to integrate elements that are put forth by the child. Furthermore, adults should accept that their behaviour towards the child may influence the child’s capacity and, consequently, they have an obligation to identify whether they are hampering the patient’s abilities and what they could do to promote capacity.

Drawing from Leila’s example presented in the introduction, this would require her parents and physician to recognize that Leila’s strong emotional response might contain an important critical reflection which she is unable to verbalize. As agreeing to their earlier judgment did not produce the desired outcome, Leila’s refusal might be construed as contradicting what adults think is best for her. Her parents’ inability to acknowledge the reasons for her choice may restrict Leila’s capacity as they are unable to help her identify what, in their view, is crucial for the decision-making process. While a procedural account does not provide guidance in situations of conflict and a strong substantive approach would inappropriately restrict children’s choice, the weak substantive account of capacity emphasizes mutual engagement and communication. Overall, this approach emphasizes exchange and sharing of perspectives which may lead to understanding diverging positions, overcoming differences, and engaging with the child in the decision-making process by opening room for consensus or compromise.

Although aspects of a weak substantive account are already practiced in shared decision-making with children (Hinds et al. 2005; Whitty-Rogers et al. 2009), it seems important to also aim at a clear theoretical conceptualization in paediatrics (Ruhe et al. 2014). A weak constitutive conceptualization of capacity is better suited for paediatrics because it can address the problems identified in the introduction to this paper. First, it makes adults’ preconceived ideas of what is best for the child explicit and specifically integrates them into a framework. This seems more reflective of the reality in paediatrics and hence more appropriate then pretending these expectations do not exist. Furthermore, in acknowledging the importance of social others for capacity, the status approach is weakened because adults are given their share of responsibility for the capacity of the child; that is, they are obliged to create a flourishing environment and provide assistance in developing and exercising capacity. Hence, the burden of proof is shifted. Furthermore, a relational approach allows transcendence of highly individualized notions of capacity and reflects the embeddedness of children. This could empower children in healthcare because it would acknowledge them as developing agents who rely on social interaction to become good decision-makers. By putting the assumption of incapacity of children on hold and accepting responsibility for their decision-making abilities, we create room for growth and the exploration of potentials. On the other hand, if we continue to see children as not having capacity, we may not provide the room necessary for demonstrating and developing their abilities, which will only confirm our initial assumption. From a relational perspective, capacity should not only inform us about the extent of children’s involvement and agency but also about the environmental aspects of such participation (Graham and Fitzgerald 2010). Acknowledging the relational dimension of capacity would also reflect the essentially triadic nature of interactions when caring for a child patient. The context of decision-making in paediatrics is demanding in that it is usually comprised of three parties—physician, parents, and patient—who need to cooperate for various tasks in varying degrees (Gabe, Olumide, and Bury 2004). Furthermore, it may become a useful tool for paediatricians as it would prompt them to continuously reflect on their own practice while also taking into account factors such as child rearing, parenting styles, and parent-child relationship apart from children’s knowledge and abilities.

Conceptualizing capacity as relational, however, bears several problems that can be identified. First, as indicated by Mackenzie, a weak substantive account entails some kind of perfectionism. Accepting adults’ decisions as an example for a good outcome requires that their decision-making process lives up to high standards and that they are able to adequately reflect upon values and assumptions they base their view on. Since the weak substantive approach obliges adults to make these reflections explicit, it highlights flaws or preconceived judgements. However, it seems reasonable to require all parties to aspire to certain standards in decision-making affecting important topics such as healthcare and treatment. Second, in cases of persistent conflict, the approach does not specify whose decision takes precedence. Yet, since a weak substantive framework emphasizes mutual understanding, it opens room for compromise, leading the focus away from who eventually makes the decision to reaching consensus. Third, the requirement for engagement in decision-making itself bears the possibility for further conflict and may in some cases aggravate the situation. This can be rebutted by pointing out that this approach places great interest on the perspective of each party thus requiring commitment of all to appreciate differing opinions rather than dismissing them. Additionally, the new approach can lead to greater understanding among all parties, thereby reducing conflict. Fourth, this approach is not a strong account as it neither specifies what a “good” decision is nor does it provide parents with means to override children’s decision when the consequences are severe or irreversible. Since we emphasize the value of each person’s perspective, it would contradict the mutual engagement, collaboration, and compromise that are central to this weak constitutive conceptualization if we were to specify what should be done in situations where, for example, there may be an option which is “objectively” the best (e.g., a 70 per cent chance of cure against only 30 per cent for another option). Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, it would defeat capacity’s gatekeeping function to autonomy. In such situations, we trust one party to be able to find adequate arguments for this best option and the other party to be equally able to understand and appreciate them. Of course, this would leave a certain number of situations where conflict could not be solved and where our weak substantive approach would not provide sufficient guidance as to how to proceed further. However, the number of such conflicts may be substantially reduced by applying this reconceptualization of capacity. Overall, we believe that this approach bears great potential for paediatric healthcare and may lead to greater involvement of children in decision-making concerning their treatment. This approach is more reflective of children’s developing nature and accounts for their embeddedness while at the same time providing means to improve current practice. We are aware that capacity and autonomy are both concepts that cannot be “outsourced,” thus, they are not transferable to others. However, by focusing on the social context, we hope to emphasize that capacity should be conceptualized similarly to autonomy, which is a positive right, and thus requires others to create an environment where children’s decision-making skills can blossom.Footnote 3

Conclusion

In this paper we have demonstrated that the idealistic view of the independent individual has influenced the concept of autonomy as much as that of capacity. Feminist critique points out that by visualizing an autonomous being as somebody self-determined, independent, and completely free of any influence, we exclude a number of individuals from ever living up to these criteria (Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000). Children are, possibly more than any other group in society, deeply entrenched with their caregivers and their environment. Thus, a conceptualization of capacity that strongly emphasizes individual abilities weakens children’s position in healthcare and may only favour those of exceptional maturity and rationality. If capacity is seen as originating from and being shaped by social interactions, an important shift in burden of proof occurs. It is no longer the child’s responsibility to “perform” her capacity but that of the adults to create an environment that allows her to exercise and learn to make decisions. It is not enough to be satisfied with what a child is able to do but to think about “cues” that could help her in her potential for capacity. Parents and healthcare professionals would need to reflect on their own role in children’s abilities to understand the situation and options at hand. By integrating Vygostky’s ideas, rather than seeking a Piagetian demonstration of skills, they would be more committed to the development and learning of capacity. Moving away from an overly individualistic conceptualization of capacity creates room for children to become actively involved in questions pertaining to their illness and treatment.

Notes

In the United Kingdom, the concept of capacity carries legal connotations and competence clinical ones (Bielby 2013).

This contextualized and social decision-making process is not unique to childhood but is also beneficial in adult care. We thank the anonymous reviewer for highlighting this important aspect.

References

Alderson, P. 1992. In the genes or in the stars? Children’s competence to consent. Journal of Medical Ethics 18(3): 119–124.

———. 2003. Die autonomie des kindes: Über die selbstbestimmungsfähigkeit von kindern in der medizin [Children’s autonomy: On children’s capacity to make decisions in healthcare]. In Das kind als patient—Ethische konflikte zwischen kindeswohl und kindeswille [Children as patients: Ethical conflicts between the child’s welfare and the child’s wishes], ed. C. Wiesemann, A. Dörries, G. Wolfslast, and A. Simon, 28–47. Frankfurt/Main: Campus Verlag.

———. 2007. Competent children? Minors’ consent to health care treatment and research. Social Science and Medicine 65(11): 2272–2283.

Alderson, P., and J. Montgomery. 1996. Health care choices: Making decisions with children, Vol. 2. Institute for Public Policy Research.

Alderson, P., K. Sutcliffe, and K. Curtis. 2006. Children’s competence to consent to medical treatment. Hastings Center Report 36(6): 25–34.

Appelbaum, P.S. 2007. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. New England Journal of Medicine 357(18): 1834–1840.

Banner, N.F. 2013. Can procedural and substantive elements of decision-making be reconciled in assessments of mental capacity? International Journal of Law in Context 9(01): 71–86.

Beauchamp, T.L., and J.F. Childress. 2001. Principles of biomedical ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bielby, N.F. 2013. Can procedural and substantive elements of decision-making be reconciled in assessments of mental capacity? International Journal of Law in Context 9(1): 71–86.

Buchanan, A.E., and D.W. Brock. 1989. Deciding for others: The ethics of surrogate decision making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brainerd, C.J. 1978. The stage question in cognitive-developmental theory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1(02): 173–182.

Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chaiklin, S. 2003. The zone of proximal development in Vygotsky’s analysis of learning and instruction. In Vygotsky’s educational theory in cultural context, ed. A. Kozulin, B. Gindis, V.S. Ageyev, and S.M. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Charland, L. 2011. Decision-making capacity. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://seop.illc.uva.nl/entries/decision-capacity/. Accessed June 13, 2015.

———. 1998. Appreciation and emotion: Theoretical reflections on the MacArthur treatment competence study. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 8(4): 359–376.

Christman, J. 2003. Autonomy in moral and political philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/autonomy-moral/. Accessed June 12, 2014.

———. 2004. Relational autonomy, liberal individualism, and the social constitution of selves. Philosophical Studies 117(1): 143–164.

Cornock, M. 2010. Hannah Jones, consent and the child in action: A legal commentary. Paediatric Nursing 22(2): 14–20.

Dittmann, V. 2008. Urteilsfähigkeit als Voraussetzung für Aufklärung und Einwilligung. Therapeutische Umschau 65(7): 367–370.

Etchells, E., G. Sharpe, C. Elliott, and P.A. Singer. 1996. Bioethics for clinicians: 3. Capacity. Canadian Medical Association Journal 155(6): 657–661.

Freeman, M. 2005. Rethinking Gillick. International Journal of Children’s Rights 13: 201–217.

Gabe, J., G. Olumide, and M. Bury. 2004. “It takes three to tango”: A framework for understanding patient partnership in paediatric clinics. Social Science & Medicine 59(5): 1071–1079.

Ganzini, L., L. Volicer, W.A. Nelson, E. Fox, and A.R. Derse. 2004. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 5(4): 263–267.

Gilligan, C. 1982. In a different voice: Harvard University Press.

Graham, A., and R. Fitzgerald. 2010. Children’s participation in research. Some possibilities and constraints in the current Australian research environment. Journal of Sociology 46(2): 133–147.

Grisso, T., and L. Vierling. 1978. Minors’ consent to treatment: A developmental perspective. Professional Psychology 9(3): 412–427.

Held, V. 1993. Feminist morality: Transforming culture, society, and politics: University of Chicago Press.

———. 2007. Feminism and moral theory. Bioethics: An introduction to the history, methods, and practice: 158.

Hickey, K. 2007. Minors’ rights in medical decision making. JONAS Healthcare Law, Ethics, and Regulation 9(3): 100–104.

Hinds, P.S., D. Drew, L.L. Oakes, et al. 2005. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 23(36): 9146–9154.

Holaday, B., L. Lamontagne, and J. Marciel. 1994. Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development: Implications for nurse assistance of children's learning. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing 17(1): 15–27.

Inhelder, B., H. Sinclair, and M. Bovet. 1974. Learning and the development of cognition. Translated by S. Wedgwood. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press.

Larcher, V., and A. Hutchinson. 2010. How should paediatricians assess Gillick competence? Archives of Disease in Childhood 95(4): 307–311.

Lo, B. 1990. Assessing decision‐making capacity. Journal of Law, Medicine and Health Care 18(3): 193–201.

Mackenzie, C. 2008. Relational autonomy, normative authority and perfectionism. Journal of Social Philosophy 39(4): 512–533.

Mackenzie, C., and W. Rogers. 2013. Autonomy, vulnerability and capacity: A philosophical appraisal of the Mental Capacity Act. International Journal of Law in Context 9(01): 37–52.

Mackenzie, C., and N. Stoljar. 2000. Relational autonomy: Feminist perspectives on automony, agency, and the social self. New York: Oxford University Press.

Marti, E. 1996. Mechanisms of internalisation and externalization of knowledge in Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s theories. In Piaget - Vygostky, The social genesis of thought, ed. A. Tryphon and J. Vonèche. East Sussex: Psychology Press.

Melton, G.B. 1983. Children’s competence to consent. In Children’s competence to consent, ed. G.B. Melton, G.P. Koocher, and M.J. Saks, 1–18. United States: Springer.

Mercurio, M.R. 2007. An adolescent’s refusal of medical treatment: Implications of the Abraham Cheerix case. Pediatrics 120(6): 1357–1358.

Miller, P.H. 1993. Theorien der entwicklungspsychologie [Theories in Developmental Psychology]. Heidelberg: Spektrum Akademischer Verlag.

Miller, R. 2011. Vygotsky in perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Morrison, K.L., J.K. Morrison, and S. Holdridge-Crane. 1979. The child’s right to give informed consent to psychiatric treatment. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 8(1): 43–47.

Murray, F. 1983. Learning and development through social interaction and conflict: A challenge to social learning theory. Piaget and the foundations of knowledge: 231–247.

Peter, C. 2008. Die Einwilligung von minderjährigen in medizinische eingriffe [Minors‘ consent in medical interventions]. Schweizerische Ärztezeitung 89(36): 1539–1540.

Peter, E., and J. Liaschenko. 2013. Moral distress reexamined: A feminist interpretation of nurses’ identities, relationships, and responsibilites. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 10(3): 337–345.

Piaget, J. 1972. Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Human Development 15(1): 1–12.

Rogoff, B., C. Mosier, J. Mistry, and A. Göncü. 1993. Toddlers’ guided participation with their caregivers in cultural activity. In Contexts for learning: Sociocultural dynamics in children’s development, ed. E.A. Forman, N. Minick, and C.A. Stone, 175–179. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ruhe, K.M., T. Wangmo, D.O. Badarau, B.S. Elger, and F. Niggli. 2014. Decision-making capacity of children and adolescents—Suggestions for advancing the concept’s implementation in pediatric healthcare. European Journal of Pediatrics 174(6): 1–8.

Sametz, L. 1979. Children, law and child development: The child developmentalist’s role in the legal system. Juvenile and Family Court Journal 30(3): 49–67.

Siegel, L.S. 1993. Amazing new discovery: Piaget was wrong! Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 34(3): 239–245.

Siegel, L.S., and B. Hodkin. 1982. The garden path to the understanding of cognitive development: Has Piaget led us into the poison ivy? In Jean Piaget: Consensus and controversy, ed. S. Modgil and C. Modgil, 239–245. London: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Sjöstrand, M., S. Eriksson, N. Juth, and G. Helgesson. 2013. Paternalism in the name of autonomy. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 38(6): 710–724.

Stier, S. 1978. Children’s rights and society's duties. Journal of Social Issues 34(2): 46–58.

Stoljar, N. 2013. Feminist perspectives on autonomy. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-autonomy/. Accessed December 6, 2014.

Tryphon, A., and J. Vonèche. 2013. Piaget Vygotsky: The social genesis of thought. New York: Psychology Press.

Vygotsky, L.S. 1978a. Interaction between learning and development. In Readings on the development of children, ed. M. Gauvain and M. Cole, 34–41. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

———. 1978b. Internalization of higher psychological functions. In Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes, ed. M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, and E. Souberman, 52–57. Cambridge, Massachussets: Harvard University Press.

———. 1986. Thought and language. Cambridge: The Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Whitty-Rogers, J., M. Alex, C. MacDonald, D.P. Gallant, and W. Austin. 2009. Working with children in end-of-life decision making. Nursing Ethics 16(6): 743–758.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ruhe, K.M., De Clercq, E., Wangmo, T. et al. Relational Capacity: Broadening the Notion of Decision-Making Capacity in Paediatric Healthcare. Bioethical Inquiry 13, 515–524 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-016-9735-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-016-9735-z