Abstract

Bystander action is a critical component of dating and sexual aggression prevention; however, little is known about barriers and facilitators of bystander action among high school youth and in what situations youth are willing to engage in bystander action. The current study examined bystander action in situations of dating and sexual aggression using a mixed methodological design. Participants included primarily Caucasian (83.0 %, n = 181) male (54.6 %, n = 119) and female (44.5 %, n = 97) high school youth (N = 218). Most (93.6 %) students had the opportunity to take action during the past year in situations of dating or sexual aggression; being female and histories of dating and sexual aggression related to bystander action. Thematic analysis of the focus group data identified barriers (e.g., the aggression not meeting a certain threshold, anticipated negative consequences) to bystander action, as well as insight on promising forms of action (e.g., verbally telling the perpetrator to stop, getting a teacher); problematic intervention methods (e.g., threatening or using physical violence to stop the perpetrator) were also noted. Implications for programming are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A growing body of research has documented the alarmingly high rates of dating (physical, sexual, and psychological aggression that happens between current or former dating partners) and sexual (any unwanted sexual behavior ranging from sexual contact to completed rape that can occur between individuals in any type of relationship) aggression among high school youth (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014; Hamby et al. 2011). Research also documents the deleterious psychological, physical, interpersonal, and academic consequences associated with dating and sexual aggression (Black et al. 2011; Coker et al. 2002), which underscores the critical importance of developing and implementing evidence-based dating and sexual aggression prevention efforts for adolescents. Dating and sexual aggression often co-occur and share many of the same etiological risk factors, and are thus often examined together in research and targeted concurrently in prevention programming (Foshee et al. 2004; Hamby and Grych 2013).

One type of prevention effort that has been recognized as a critical component to dating and sexual aggression programming is bystander education and training (Banyard 2013; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014). Such programs help participants as potential bystanders develop behaviors that aid in the prevention of dating and sexual aggression and assist in victims’ recovery from dating and sexual aggression experiences (Banyard 2013). To address bystander action in programming efforts, it is important to understand the factors that facilitate or hinder bystander action. Accordingly, there is a burgeoning body of literature examining the factors related to dating and sexual aggression bystander action among college students (e.g., Banyard and Moynihan 2011; Bennett et al. 2014), rural young adults (e.g., Edwards et al. 2014), and urban populations (e.g., Frye 2007; Frye et al. 2008).

However, far less research has focused on dating and sexual aggression bystander action among high school youth (e.g., McCauley et al. 2013; Noonan and Charles 2009; Van Camp et al. 2014), and no research has specifically examined dating and sexual aggression bystander actions using a mixed methodological approach with high school youth, which was the focus of the current study. A better understanding of the facilitators and barriers to bystander action in situations of dating and sexual aggression among high school youth as well as the specific situations in which helping happens and the methods used could be useful for creating and tailoring dating and sexual aggression prevention programming. Mixed methodological research is especially important when studying bystander action given that it allows researchers to examine the prevalence and quantitative correlates of dating and sexual aggression bystander action as well as collect rich detail about the language youth use when discussing both dating and sexual aggression bystander action, all of which are important in the development of age-appropriate and relevant prevention.

Bystander action has historically been guided by the framework proposed by Latane and Darley (1970), and more recently has been adapted for dating and sexual aggression by Banyard (2011) to include relational and community factors that may impact bystander action. Latane and Darley’s (1970) model asserts that bystander action involves first noticing the situations as problematic, assuming responsibility to do something about it, creating a course of action for what must be done, and lastly, choosing to act. Banyard (2011) expanded this model and suggested that intrapersonal variables (e.g., gender and attitudes towards violence) and contextual variables (e.g., closeness to the victim, severity of the situation) may also impact dating and sexual aggression bystander action behaviors. Although these individual, relational, and contextual correlates have been studied extensively with adult populations (e.g., see Banyard 2011 and Bennett et al. 2014 for reviews), only a handful of studies have examined correlates and perceptions of dating and sexual aggression bystander action among high school youth.

Guided by Banyard’s (2011) theoretical model, we chose to focus on demographic, attitudinal, and behavioral correlates of bystander action. Specifically, we were most interested in the role of gender and age, rape myth acceptance, and a history of physical and sexual dating aggression victimization, since these are frequently-studied correlates of dating and sexual aggression bystander action among adults (Banyard 2008; Brown et al. 2014; Burn 2009; Koelsch et al. 2012; McMahon 2010), as well as correlates of dating and sexual aggression perpetration (Basile et al. 2013; de Bruijn et al. 2006; Reyes and Foshee 2013, Wolitzky-Taylor et al. 2008). Furthermore, debunking rape myths is a key component of bystander-focused dating and sexual aggression prevention programming with college students (Eckstein et al. 2013; McMahon 2010). To date, however, little research has examined these demographic, attitudinal, and behavioral correlates of bystander action among youth.

Among the limited studies with youth to date, research generally finds that boys are less likely to intervene in dating aggression situations than girls (Jaffe et al. 1992; Van Camp et al. 2014). Further, although Van Camp et al. (2014) found that a history of dating aggression victimization was unrelated to likelihood of intervening in situations of dating aggression among Canadian high school youth, McCauley et al. (2013) found that as likelihood to intervene in dating aggression situations increased among high school athletes, the likelihood of perpetrating dating aggression decreased. Although not yet studied with high school samples, research with adult samples has found that there may be other important demographic (e.g., less bystander action with increased age) and attitudinal (e.g., less bystander action among individuals high in rape myth acceptance) correlates of bystander action and non-action (see Banyard 2008 and Banyard and Moynihan 2011 for a reviews).

Although a few survey-based studies have examined dating and sexual aggression bystander action among high school youth, no studies to date have examined perceptions of bystander action using a qualitative methodology among high school youth. Qualitative methodologies are especially important for examining relatively new fields of inquiry, such as dating and sexual aggression bystander action among youth, in order to build theory and obtain specific details of situations and languages that can be directly incorporated into prevention program materials. Though there are no studies to date with high school youth, Noonan and Charles (2009) conducted focus groups with middle school youth and found that youth were more likely to report intentions to intervene in situations of physical dating aggression compared to situations of emotional and verbal dating aggression. Youth reported that they would be less likely to intervene if the perpetrator was not a close friend. Non-action was related to concerns about being a “snitch” as well as concerns about personal safety. Providing advice (i.e., most commonly to terminate the abusive relationship) to victims was reported as a common action method (Noonan and Charles 2009). In another qualitative study of urban, African-American middle school youth, Weisz and Black (2008) found that bystander non-action was the most common hypothetical response to a video vignette depicting a boy abusing his girlfriend. Reasons for non-action were primarily because youth believed it was not their business or concerns they would get hurt or in trouble. Although specific to bullying, Ferrans et al. (2012) conducted in-depth interviews with 8th graders and found that bystander action was impacted by youth’s interpretation of the underlying nature of the situations (e.g., joke vs. gone too far), relationship with the victim and perpetrator, feelings of moral responsibility, and power status in the relationship.

Although our knowledge of dating and sexual aggression bystander action has increased, there remains a dearth of research that has focused on high school youth using both quantitative and qualitative methods. While there are many similarities in adolescents and young adults dating experiences as well as middle and high school youths dating experiences, there are documented developmental differences (e.g., adolescents have less monogamous relationships than young adults; adolescents use less words than younger adults during conflict resolution; more pronounced gendered dating attitudes and behaviors in adolescence than young adulthood; Lanza and Collins 2008; Markiewicz et al. 2006; Norona et al. 2013). Furthermore, adolescent romantic relationships in early adolescence differ from those in mid-to late adolescence in duration (i.e., relationships in early adolescence are shorter than relationships in mid-to-late adolescence) and social function (i.e., relationships in early adolescence are driven more by enhancing peer group status, whereas relationships in mid-to-late adolescence are based more on intimacy and companionship; Furman and Wehner 1997). Thus, we cannot assume that bystander action in dating and sexual situations among high school students would be the same as bystander action among middle school youth or adult populations. Also, the benefit of using a mixed methodological design is that we can examine the prevalence and quantitative correlates of dating and sexual aggression bystander action as well as collect rich detail about the language youth use when discussing both dating and sexual aggression bystander action, all of which are important in the development of age-appropriate and relevant prevention programming.

The Current Study

The current study was largely descriptive and utilized a mixed methodological approach to shed light on the following questions: (1) To what extent do high school youth report engaging in actual dating and sexual aggression bystander action behaviors and how do gender, age, dating during the past year, rape myths, and sexual and dating aggression victimization correlate with these bystander action behaviors? (2) What are the factors that facilitate or hinder students’ engagement in dating and sexual aggression bystander action behaviors? (3) What are the situations in which students’ engage in dating and sexual aggression bystander action behavior and what are the specific methods in which students engage in these behaviors? Whereas the first research question was examined using survey data from students, the second and third research questions were examined using qualitative focus group data.

These are important questions to empirically examine given the understudied nature of bystander action among youth in situations of dating and sexual aggression, and the implications of such findings for the development of bystander-focused prevention programming. Given the dearth of research to date and the largely qualitative focus of this study, we posed research questions as opposed to a priori hypotheses. Although dating and sexual aggression often co-occur with other forms of aggression, such as bullying, we chose to focus on dating and sexual aggression in this study for three reasons. First, there is limited research to date with youth on bystander action in situations of dating and sexual aggression, especially in comparison to other forms of aggression (e.g., bullying). Second, research suggests that bullying typically declines during the high school years and aggression in dating and sexual relationships often increases during the high school years (Espeleage et al. 2014). Lastly, we had a limited amount of time to conduct surveys and focus groups with students, which precluded us from administering more comprehensive surveys and broadening the scope of our focus group discussions.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 218 high school youth from three high schools in New England (one rural, two urban, USA). A slight majority (54.6 %, n = 119) identified as male, (44.5 %, n = 97) identified as female, and (0.9 %, n = 2) identified as “other.” The average participant age was 15.56 (SD = 1.32, range = 13–18). Nearly half (46.8 %, n = 102) of the sample was in 9th grade, (8.7 %, n = 19) were in 10th grade, (24.3 %, n = 53) were in 11th grade, and (20.2 %, n = 44) were in 12th grade. The majority of participants were Caucasian (83.0 %, n = 181); (15.6 %, n = 34) were a racial minority (either Asian/Pacific Islander, Black/African American, or Hispanic/Latino), and (1.4 %, n = 3) “did not know.”Footnote 1 Two thirds (67.9 %, n = 148) of participants had dated during the past year. Although not directly assessed in the survey due to space constraints, based on Department of Education data, 37.0 % of kids in our participating schools received free or reduced lunch, a liberal index of poverty.

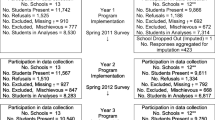

Procedure

These data come from a larger study that included survey and focus group data collection with youth and focus group data collection with teachers. In this article, we report the student data; the teacher data is reported in another article (Edwards et al. 2015). Data collection procedures with students included obtaining parental consent/student assent, survey completion, focus group participation, and debriefing and referral information. The principals were asked to select the classrooms of students that would provide a representative sample of the student body. For their participation in the study procedures, students received a bottle of water and a healthy snack. Two of the three high schools allowed for passive parental consent, whereas one school required active parental consent. Students under 18 whose parents consented provided assent before participating, and students who were 18 provided consent. Parents who did not consent (or students who did not assent) were given a pass to the library to study.

After the consenting and assenting procedures, students completed surveys in gender-specific groups. To be mindful of gender variant identities, students were told that they could participate in whichever group they felt most comfortable. Surveys took approximately 15 min to complete. At two schools, the focus groups occurred immediately after completing the survey, whereas at one school who had a different class schedule, the focus groups occurred 2 days after the initial survey. All procedures took place during class time in classrooms.

Steps were taken to minimize risks. First, participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the study and instructed that they could withdrawal from participating at any point without penalty. Second, surveys were anonymous and students and their parents/guardians were informed of this. Third, we urged students to use non-identifying examples in the focus groups so as to protect their and other students’ confidentiality. Following the study procedures, students received local referral and debriefing information and an advocate from a local crisis center was with the research team during all data collection procedures. All study procedures were approved by the University of New Hampshire Institutional Review Board.

A total of 26 student focus groups were conducted across the three participating high schools. All focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The gender-specific, student focus groups ranged in size from 7 to 13 students (Mean = 9.65, SD = 1.80). Focus group facilitators were a male-identified professor, a female-identified professor, one female-identified graduate student, a female-identified post-baccalaureate research assistant, and one female-identified advanced undergraduate students. The male-identified professor always conducted focus groups with boys, although several of the female-identified researchers conducted focus groups with boys as well when more than one focus group with boys was running concurrently. Most focus groups were individually facilitated, although a few focus groups were co-facilitated. When co-facilitation occurred, senior team members were matched with more junior interviewers. However, all facilitators had previous interviewing experience and previous experience conducting clinical and/or advocacy work related to dating and sexual aggression. Moreover, all facilitators were highly trained on the current protocols prior to facilitating a focus group.

The interview script was semi-structured and asked broad questions regarding: (1) how peers help peers (as victims, perpetrators, or both) in situations of dating and sexual aggression, (2) situations when students have the opportunity to intervene, (3) barriers and facilitators to intervening in situations of dating and sexual aggression, and (4) the ways in which students help in situations of dating and sexual aggression. At the start of the focus group, there was discussion about the specific terms that students use to describe the phenomenon under study and thereafter students’ terminology (e.g., “dating”, “going out”, “hooking up”, “domestic violence”, “abusive relationship”) were used by the interviewer throughout the focus group. To begin conversations about dating and sexual aggression, focus group facilitators asked students “When it comes to relationship what are some of the problems or challenges teenagers face?” If students did not readily identify dating and sexual aggression as issues, the focus group facilitators said something along the lines of: “In addition to issues such as [whatever they say as issues], one of the things we know is that a number of teens have trouble with what we call dating violence. There are a lot of different terms used to describe what we are talking about like dating violence, domestic violence, partner violence, and relationship abuse. Now we would like to ask you some questions about your opinions about dating violence.” Student focus groups lasted on average 39.35 min (SD = 11.66 min, range 18.28–64.50 min).

Survey Measures

Bystander Action

We used 13 dating and sexual aggression items from the 26-item Bystander Behavior Scale (Banyard 2008) to determine the extent to which youth intervened in situations of dating and sexual aggression during the past year. In consulting with the developers of this measure, we excluded 13 of the 26 items due to the content being less relevant to high school students than college students (“Told a friend I thought their drink may have been spiked with a drug”) or because they measured bystander action in situations that were not relevant to dating and sexual aggression (e.g., “Indicated my displeasure when I heard a homophobic joke.”) (Victoria Banyard, personal communication, November 2013). Most of the 13 items inquire about bystander action in situations involving friends or peers although a few of the items are more general (“Spoke up if I heard someone say: ‘She deserved to be raped,’”). For each of the items, participants responded with either “yes” (participants witnessed the behavior and engaged in the behavior described), “no” (participants witnessed the behavior but did not engage in the behavior described), or “no” opportunity (participants did not witness the behavior). Participants were also provided with the definitions of dating aggression (“when someone you are going out with physically [e.g., hitting, slapping, pushing] or emotionally [e.g., calling you mean names, spreading rumors about you, etc.] hurts you on purpose. [Dating aggression] can also include [sexual aggression]”) and sexual aggression (“when someone forces you to do sexual things that you did not want to do”) since some questions specifically use this phrasing (e.g., “Talked with my friends about sexual assault and [dating aggression] as an issue for our community.”). Items were examined separately and scored in order to create an overall ratio of bystander action (i.e., total number of situations in which one intervened/total number of situations in which one had the opportunity to intervene). The validity of this scale was established in prior research (Banyard 2008).

Dating and Sexual Aggression Victimization

We used two items from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013) to ascertain physical dating aggression victimization (“During the past 12 months, how many times did someone you were dating or going out with physically hurt you on purpose? [Count such things as being hit, slammed into something, or injured with an object or weapon.]”) and sexual victimization (“Have you ever been physically forced to have sexual intercourse when you did not want to?”). Both variables were scored separately and dichotomized so that zero represented no victimization and one represented victimization. Individuals who had not dated during the past year were excluded from calculating the incident rate for physical dating aggression victimization.

Attitudes Towards Dating Violence

We used the acceptance of dating abuse (prescribed dating abuse norms; Foshee et al. 1998; Foshee and Langwick 2010), which consists of eight items assessing both female-to-male dating aggression (e.g., “It is OK for a girl to hit a boy if he hit her first.”) and male-to-female dating aggression (e.g., “Girls sometimes deserve to be hit by the boys they date.”). Response options range from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (4). Items are summed so that higher scores are indicative of higher levels of accepting attitudes towards dating violence. In the current study Cronbach’s alpha was 0.74, which similar to what was reported by Foshee et al. (2005) (alpha = .78).

Rape Myths

We used the Updated Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (McMahon and Farmer 2011), which consists of 22 items (e.g., “If a girl is raped while she is drunk, she is at least somewhat responsible for letting things get out of hand.”). Response options range from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). Items are summed so that higher scores are indicative of higher levels of rape myth acceptance. In the current study Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93, which consistently with what McMahon and Farmer (2011) reported (Cronbach’s alpha = .87).

Analysis Plan

The quantitative data was analyzed using SPSS 21. We conducted descriptive statistics to document the extent to which students have the opportunity to intervene in situations of dating and sexual aggression and the frequency with which students intervene when given the opportunity. We were also particularly interested in the specific situations that have the highest and lowest rates of bystander action, and the correlates (i.e., demographic variables, rape myths, accepting attitudes towards dating violence, dating and sexual aggression victimization) of these action behaviors.

Missing data on scales of interest ranged from 0 to 12.4 %. All measures had 0–2 % of missing data with the exception of the bystander behavior scale that had 12.4 % of participants missing data on this measure. We believe that missing data was higher on this scale due to some students’ confusion with this measure. Anecdotally, missing data was often due to double circled answers (circling both “yes” and “no” or circling “yes” and “no opportunity). Given generally low rates of missing data and that we did not want to use mean imputations on behavioral experiences given the largely descriptive focus of this study, we eliminated individuals from selected analyses in which they were missing data on the variable being analyzed (e.g., for example, a participant missing data on gender, but who has data on bystander action and age would be excluded from the analysis correlating gender and bystander action, but included in the analysis correlating bystander action and age).

The qualitative data was analyzed by using thematic analyses (Braun and Clarke 2006; Miles and Huberman 1994). Thematic analysis has been defined as a “method of identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 7). NVivo was used to facilitate the coding process. To increase credibility and validity of the analyses, the first and second author completed all steps of the coding detailed below and the third author participated in some of the discussion throughout the process in addition to reading all of the transcripts. Consistent with the method outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006), we first read through the transcripts several times to immerse ourselves in the data and obtain the gestalt of the data. Second, we met on several occasions to discuss and create initials codes that were derived inductively from the data. Third, we again read through all of the transcripts and systematically coded them using NVivo. Fourth, we engaged in another series of meetings to aggregate the codes into potential themes. Fifth, we re-read all of the transcripts to ensure that the coding units and over-arching themes were congruent with all of the data and refinements were made as needed. In general, in order to qualify as a major theme (e.g., specific barrier to bystander action), it needed to be present in a majority of the focus groups. As we summarize the qualitative findings below, we provided sample quotations which were modified slightly at times to enhance readability (e.g., removing excess “like” and “umm”).

Results

Student Survey Data

Almost all (93.6 %) students had the opportunity to intervene during the past year in situations of dating or sexual aggression (see Table 1 for a list of situations). In fact, during the past year, students had the opportunity to intervene in at least 5.63 (SD = 3.62) situations of dating and sexual aggression; note that this number does not represent the number of times youth had the opportunity to take bystander action, but rather the number of different types of situations that youth had the opportunity to take bystander action. Of youth who had the opportunity to take bystander action in at least one situation, 37.4 % of youth reported at least one instance of bystander non-action. This number (37.4 %) should be interpreted with caution since we do not know if a participant had more than one opportunity to intervene in a given situation or if they intervened more than once in a given situation. Put another way, we do not know the exact number of times individuals had the opportunity to intervene (just that they had the opportunity) per situation, nor do we know the exact number of times individuals actually intervened when given the opportunity (just if they have intervened at least once or if they have not intervened at least once). However, it is likely that students who had multiple opportunities to intervene, answered about their bystander action or non-action behaviors based on their most common response (e.g., if they took action one time, but non-action multiple times, they would presumably be most likely to respond that they took non-action to the item).

Based on individual item analyses (see Table 1), students with the opportunity were most likely to intervene when they heard someone say “she deserved to be raped” (56.8 %), when a friend’s boyfriend or girlfriend was exhibiting jealous or controlling behavior (61.5 %), when they believed their friend was in an abusive relationship (54.2 %), and when they heard a friend insulting their partner (51.3 %). Students were least likely to intervene in situations involving sexist jokes (35.2 %), catcalls (e.g., whistling at a girl; 31.2 %), and when a friend was being taken upstairs at party and appeared very intoxicated (14.0 %).

Girls (M = 0.47, SD = 0.38) were more likely to intervene in situations of dating and sexual aggression than boys (M = 0.30, SD = 0.30), t(187) = 12.403, p < .01, Cohen’s d = 0.50. Youth with histories of dating aggression (M = 0.66, SD = 0.31) [t(131) = 2.58, p < .05, Cohen’s d = 0.92] and sexual aggression (M = 0.64, SD = 0.31) [t(189) = 2.77, p < .01, Cohen’s d = 0.86] were more likely to intervene in situations of dating and sexual aggression than youth without dating aggression (M = 0.37, SD = 0.32) and sexual aggression (M = 0.36, SD = 0.34) histories. However, there were no significant relationships between dating and sexual aggression bystander action and rape myths (r = −.08, p = .25), attitudes towards dating violence (r = .01, p = .90), or year in school (r = .01, p = .90), or age (r = .02, p = .78). See Table 2 for additional descriptive and inferential data.

Student Focus Groups

Overarching themes to emerge from the students clustered in four areas: (1) the most common types of dating and sexual aggression in high school relationships; (2) barriers and facilitators of dating and sexual aggression bystander action; (3) dating and sexual aggression bystander action methods; and (4) ambivalent attitudes about including parents and teachers in situations of youth dating and sexual aggression. Table 3 depicts a summary of the qualitative findings.

Primary Manifestations of Dating and Sexual Aggression

Students identified a number of issues that high school students struggle with in relationships (e.g., jealousy, communication, trust, boundaries), including those that we, as researchers and practitioners, would consider to be dating and sexual aggression. We first briefly summarize what students identified as the most common types of dating and sexual aggression in relationships since these provide insight into the types of situations in which students have the opportunity to intervene.

Although in most focus groups students could identify several examples of physical dating aggression involving students in their school, youth articulated that sexual pressure (“taking advantage of girls when they are drunk”; “I’ll have sex with you if you come with me to see this movie or go to this concert”; “it is usually an older guy with a younger girl and the younger girl feels that she has to be sexually pleasing to the older guy”; “sexual pressure is a pretty big deal”), verbal and emotional abuse (e.g., “yelling at each other”), and stalking and controlling behaviors (e.g., “people can get really controlling and manipulative… if you want to hang out with the person you are dating and they said ‘no’ you would try to make the feel really bad so they would [want to hang out with you]”; [a guy standing] outside of his girlfriend’s class every day, the same class, the same period and waits for her to like leave class to go to like the bathroom”) were much more pervasive problems in dating relationships. Students also articulated that a large portion of dating and sexual aggression happened over social media (e.g., “people will see [the dating couple] fighting [at school] … then ten minutes, as soon as school gets out, [the fighting dating couple] will put something on Facebook [to continue the fight]”) and text messaging (“It’s very easy to sit there and not think about the consequences of what you are texting when you are so enraged.”; “when one person gets a picture of his girlfriend, and they break up, he sends pictures to his friends”).

Although students rarely identified the following words and phrases as problematic or on the continuum of sexual aggression, students reported them as common and often said in a joking context: “Slut”, “Hey, what’s up bitch?”, “T.H.O.T., that hoe over there” and other comments such as: “Your ass looks amazing in those yoga pants” and “[Are] those space pants? Because your ass is out of this world.” Despite rarely identifying them as problematic, some students acknowledged that that these types of phrases could negatively impact the students to whom they were directed. For example, one student said: “It hurts people’s feelings and some people can be depressed about it.” Another student said: “Some people are suicidal [because] when girls get called a whore they have weird emotions, they take it really deep.”

Barriers and Facilitators of Dating and Sexual Aggression Bystander Action

Thematic analyses from focus groups helped us to understand some of the reasons for non-action as well as of the factors that facilitated or hindered helping. Students provided three main types of dating and sexual aggression non-action, two of which were specific to dating and sexual aggression that took place over social media. The first was to ignore what was happening (e.g., “just let it happen,” “a lot of laughing and talking [and watching],” “I’m just going to keep walking”) in response to witnessed verbal and physical dating aggression in school hallways. They also acknowledged engaging in behaviors to encourage dating aggression witnessed on social media (e.g.“they’ll like it or favorite it”; “post like popcorn” [after inquiring about this, multiple students indicated that popcorn emoticons are used to symbolize that they are passively watching others engage in online fighting or harassment analogous to eating popcorn at a movie].) Lastly, it was noted that students often gossip or disclose incidents of abuse via social media (e.g., “start putting [photos or a summary of what is happening in a post] online”). These non-action behaviors are related to an overarching theme of “drama”, either a desire to avoid the drama, such as ignoring or walking by the dating or sexual aggression incident, or a desire to fuel the drama by encouraging the dating or sexual aggression incident directly by sharing it through social media. As an example to avoid drama, one student said “It’s just annoying drama really is what it is. You don’t even want to deal with it” and another student mentioned, “when I see [drama on social media] I leave it be.” Examples of fueling drama as a barrier to bystander action were: “Some people love drama” and “It’s like a movie you know watching them, it’s funny.”

In addition to the desire to avoid or fuel drama, students identified other factors that hindered or promoted bystander action in situations of dating and sexual aggression. Students were less likely to intervene when they felt there could be social repercussions for their action (e.g., “Nobody’s going to say anything to [the popular kids]; nobody is going to approach them if they are [engaging in aggressive behavior towards their girlfriend or boyfriend; “You don’t really want to get involved in big arguments and stuff…because then you have the girl bitchin’ at you…and other people…it causes more problems for you”]” and “I don’t want to get into this [fight]. I don’t want to choose sides.”). Students were more likely to intervene when they were friends with the involved individuals, especially when their friend was the victim (e.g., “Like if it is a close friend, I’ll step in”); students reported concerns about helping students they did not know (e.g., “like if the relationship was [with] my friend, I would let them know, but if it’s a naked picture of the person I have biology with…I wouldn’t say anything really, because… I don’t have the relationship with them, you know, [it would] be like ‘so I found that naked picture of you the other day’ and not have it be awkward,” and “no one is really going to listen to some random person that tells you what to do. If someone randomly came up to me, I would not listen to them.”).

Youth also reported that they were more likely to intervene in situations when a boy was abusing a girl and less likely when it was a girl abusing a boy, which was often viewed as funny or deserving (e.g., “If my guy friend came up to me and was like, ‘my girlfriend slapped me’ I’d be like, ‘well what did you do retard?’ If a girl came up to me and was like ‘my boyfriend just slapped me’ or ‘my boyfriend just pushed me into a wall’ I’d be like, ‘alright where is he, let me talk to him for a second.”). Students were also far more likely to report that they would intervene if the violence happened in person as opposed to over social media (“It’s actually a lot harder to [intervene] on Facebook. Because … it spreads not only from [the victim] being attacked, but to [now] you being attacked”; “[You] can’t really stop the fight [on Facebook] because I [it is not like you’re going to] drive to their house and turn the computer off. There’s nothing you can really do.”). Students were also more likely to intervene if the violence met a certain threshold, such as physical dating aggression that caused injury and/or notable emotional distress to the victim. Students also reported not intervening due to concerns about perpetrator (e.g., “[They might not intervene because they would] be scared that [the perpetrator would] do that to them too… if they can do that to [the victim], [the perpetrator] could do that to me too.”) and victim (e.g., “If you notice something is wrong, you bring it up to your friend who is in a bad relationship, [but your friend doesn’t] really acknowledge it [and your friend doesn’t] want your help, [so] how are you supposed to help them?”) reactions, as well as an inability to relate to the situation (e.g., “Sometimes you just can’t relate to what they’re arguing about, so whatever you say probably won’t even matter.”).

Ambiguity about Involving Teachers and Parents in Youth Dating and Sexual Aggression

Another major theme to emerge from the focus groups was that students were in agreement that although they considered it to be a good idea to involve a teacher or parent/guardian in situations of dating and sexual aggression when it reached a certain threshold, they also expressed hesitancy to do so. This hesitancy often centered around teachers and parents/guardians not understanding, as well as concerns that they would get in trouble or be considered a “snitch.” Some students expressed hesitancy in involving teachers and parents in situations of dating and sexual aggression because they felt “adults would make it worse.” For example, students stated that the manner in which school staff may try to resolve problem, actually exacerbates it (e.g., “the only problem is like guidance counselors, a lot of their solutions are [to] get the other person [involved] in here …and that just makes it worse.”). Students also expressed that teachers and parents may not fully understand how they perceive situations of dating or sexual aggression due to generational differences (e.g., “sometimes…they don’t see it from your point of view because they’re not your age. They’re not your peers.”). In addition students’ self-perceived a general lack of concern among teachers, especially when the dating or sexual aggression occurred outside of school (e.g., “I don’t think teachers really care either. If it’s [occurring] out of school…go at it.”), and the fear that teachers may tell others (e.g., “I kind of feel like some teachers gossip like us too.”), contributed to their reluctance to involve them. Lastly, some students felt that it may be uncomfortable discussing sensitive topics such as dating and sexual aggression with a teacher that they are not close with (e.g., “I don’t feel like you would want to talk with that teacher [you are not close with]. Cause, like, that teacher doesn’t tell you stuff…about their personal life, so…why should you tell them about your personal life?”).

Despite concerns of involving parents and teachers in situations of dating or sexual aggression, students identified reasons why the involvement of adults could be beneficial, and when teachers and parents should be involved. Some students believed it is important to involve an adult or school staff when a peer discloses dating or sexual aggression to you (e.g., “if a boyfriend or girlfriend is hitting your friend and they come to you about that… I know that you’re going to feel like ‘Oh they’re going to be pissed off at me if I go tell anybody’, but you should tell somebody like… a social worker, a guidance counselor because that’s really important.”). Students stated that parents and teacher’s life experiences may provide them with a deeper understanding of relationships and fresh perspective (e.g., “they’ve been through those same situations …[and] parents they’ve seen more about relationships and dating [which might] provide you with some insight that you never thought before.”) that other students their age may not be able to offer.

Students recognized that although peers would do their best to help in situations of dating and sexual aggression sometimes adults and teachers are needed to “step in and make some decisions, [because] sadly ‘cause were not mature enough, we don’t necessarily know all the ways to deal with a [dating or sexual aggression] situation and sort it out.” Additionally students felt that unlike peers, adults generally “relate in a better way other than [simply saying] ‘Oh yeah, I know what you mean, it’ll be okay’” which students attributed to being unhelpful in situations of dating or sexual aggression.

Students stated they would be more inclined to discuss situations of dating and sexual aggression with school staff, specifically guidance counselors they had rapport with, suggesting that if meeting with them was “mandatory you could develop a closer relationship and maybe feel friendly towards them so you could talk to them about that stuff.” Students cited benefits of involving specific school staff, particularly valuing the confidentiality provided by guidance counselors (e.g., “guidance counselor will keep it a secret”) and being more comfortable talking about dating and sexual aggression with other staff (e.g., “you can act more relaxed with your coaches and guidance counselors than teachers”). They also identified other means of involving teachers and parents, such as being able to “leave a note” with a teacher or school staff in lieu of direct communication to encourage students to come forward when they are scared to talk about it.

Sexual and Dating Violence Bystander Action Methods

Although students reported the barriers to intervening in situations of dating and sexual aggression, students also provided insight on the ways in which they do intervene in situations of dating and sexual aggression. Female students most often reported that they would talk to their friends, especially when a friend was the victim, but also discussed ways in which they would talk to a friend who was the aggressor. Male students often reported that they would resort to the use of physical aggression (e.g., “smack him across the face” and “beat his ass”) when intervening in situations of physical dating aggression. However, some male students provided more positive and promising modes of intervention, which were at times subtle (e.g., offering to dance with a girl who was being bothered by another boy, starting a conversation to interrupt the sexually aggressive behavior) and other times more direct (e.g., calling out the aggressor on his or her behavior). Both male and female students provided examples of the words they use when intervening in situations of dating and sexual aggression. For example, in response to witnessed verbal dating aggression, students said they would say, “It’s not cool, knock it off. Nobody thinks you are cool for doing it” and “Yo dude, calm down.” In response to witnessed sexual pressure, male students indicated they would say thing such as “Chill… give her a few months” and “Dude, you’re hitting on girls you have no chance with. What are you doing?” Examples of prosocial bystander responses to witnessed physical dating aggression included: “Hey don’t push my friend like that.” and “What do you think you are doing?” Finally, in response to witnessed stalking and controlling behaviors, students gave examples of verbal action such as “You just got to leave her alone. Find someone else” and “You need to stop talking to this girl. You are going to get yourself in trouble. She doesn’t like you. You need to stop before she tells the officer. You are going to get suspended. You need to stop doing that.”

Discussion

Given the high rates of dating and sexual aggression among youth and the importance of bystander action in the prevention of such aggression, the goal of this study was to gather survey and focus group data from high school youth about their experiences with and perceptions of dating and sexual aggression bystander action. The ultimate goal of this study is to inform the development of bystander-informed prevention programming with youth to reduce the incidence and prevalence of dating and sexual aggression in US society. This data is some of the first on high school students’ engagement in dating and sexual aggression bystander prevention and provided novel information on the facilitators and barriers to bystander action, detailed examples of situations in which students help, and specific behaviors and language high school students use to intervene. Results suggested that, similar to what has been documented in the bullying literature (e.g., Salmivalli et al. 1996), bystander non-action was frequent among students in situations of dating and sexual aggression. It is important to keep in mind that (aside from our single-item measure of sexual victimization), our operationalization of dating and sexual aggression in the bystander measure and in focus group discussion was very broad and inclusive. If we were to have used more restrictive definitions of dating and sexual aggression, we likely would have found even high rates of bystander action in light of research suggesting that bystander action increases with the perceived severity of the situation (Banyard 2011; Bennett and Banyard 2014); this also resonates with the threshold theme that emerged from focus group discussions in this study.

Both the qualitative and quantitative data helped us to understand the factors that facilitated or hindered helping in situations of dating and sexual aggression. Interestingly, many of the barriers and facilitators of bystander action in situations of dating and sexual aggression we documented are similar to barriers and facilitators of bystander action documented in the bullying literature (Ferrans et al. 2012; Pozzoli and Gini 2010a, b; Pozzoli et al. 2012). Girls were more likely than boys to intervene in situations of dating and sexual aggression, which is consistent with previous research (Jaffe et al. 1992; Van Camp et al. 2014). Extending previous research, we found that boys and girls also used different methods of intervention (e.g., girls were more likely to talk to the victim whereas boys were more likely to use physical aggression with the perpetrator), suggesting that gender-specific educational messages may be needed in bystander prevention programming with youth. The gender of the victim and perpetrator also impacted bystander actions, with students less likely to intervene when a boy was the victim and a girl was the perpetrator. Although research demonstrates that boys’ use of violence towards girls often results in more negative consequences (Dardis et al. 2014; Tjaden and Thoennes 2001), all forms of violence should be viewed as unacceptable, including girls use of violence against boys and violence within same-sex couples. Thus, bystander prevention programming should address myths about male victimization experiences, while providing youth the opportunity to acquire the skills and agency needed for intervening in non-heteronormative/male-perpetration and female-victim scenarios.

Consistent with a great number of earlier studies, participants in this study were more likely to engage in bystander action before, during, and after an incident of abuse or harassment if the victim was a friend as opposed to a stranger. This phenomenon has been demonstrated since some of the earliest studies on bystander action (Latane and Rodin 1969). And, more recent research indicates that this gap still exists among adults in cases of sexual assault (Burn 2009). Therefore, it is not surprising that the youth in our sample had an easier time seeing themselves intervening for people with whom they already have a relationship. There are a number of interactive exercises in current bystander intervention curriculums that aim to increase empathy for individuals with whom one does not have a close relationship (e.g., Eckstein et al. 2013). Based on these findings, any curriculum developed for high school students would similarly need to address this concern.

In addition to gender and relationship status, survey results documented an association between a victimization history and bystander action, which was further evidenced in the qualitative results (i.e., individuals who can relate/understand are more likely to intervene than those who cannot relate/understand). However, accepting attitudes towards dating and sexual aggression were unrelated quantitatively to bystander action behaviors; that is, students who reported attitudes more accepting of dating and sexual aggression were not less likely to intervene as a bystander. Therefore, it may be that that these attitudinal variables do not exert a strong influence on bystander action, and the qualitative findings may help explain this further. As documented in the qualitative data, a number of other barriers were documented in the focus group results, such as anticipated negative perpetrator and victim reactions. Thus, even if an individual is low in accepting attitudes towards dating and sexual aggression, if they have concerns about negative perpetrator and victim reactions, they may be unlikely to intervene.

The finding that accepting attitudes towards dating and sexual aggression were unrelated quantitatively to bystander action behaviors could also be due to our measurement of bystander action behavior. Although we used a widely used measure of bystander action, some of the bystander responses included in the measure are vague (e.g., “said something to them” and “spoke up”). And, we learned in our focus groups that at times, “speaking up” could be prosocial, such as telling the person the behavior was “not cool,” but at other times, it could be problematic (i.e., threatening to physically assault the perpetrator). Because we might expect different relationships between these behaviors and accepting attitudes towards dating and sexual aggression (i.e., saying the behavior is not cool negatively related to accepting attitudes; threatening to physically assault someone positively related to accepting attitudes), this could have contributed to the null finding between accepting attitudes towards dating and sexual aggression and bystander action behaviors. Clearly, this is an important area for additional research.

Furthermore, some of the identified barriers (e.g., social status and personal repercussions, not understanding or relating to the situation, not thinking it is serious enough) of dating and sexual aggression bystander action emphasize the importance of educational information, specifically helping kids without social agency to intervene in ways that feel safe to them (e.g., anonymously reporting the behavior), and the provision of empathy building activities in bystander action programming. Also, it is important that programming efforts help teens to understand the importance of bystander action even when the dating and sexual aggression may not meet the threshold of the victim being visibly hurt (physically or emotionally) given that many victims may mask their reactions to “save face” with their peers and/or protect the relationship (Edwards et al. 2012).

Additionally, for some youth, the desire to fuel drama was a barrier towards intervening, whereas other youth identified the desire to avoid drama as a barrier to intervening. This finding in our study is consistent with ethnographic research conducted by Marwick and Boyd (2014), in which these researchers documented that teenagers mislabel events of bullying as “drama” as a way to normalize bullying. This serves a dual protective function for both bullying victims (so they can “save face” and attribute the bullying behavior as the perpetrators desperation for attention) and bullying perpetrators (so they can feel as if they are engaging in something that is harmless and funny, rather than emotionally hurting the target of their bullying). There is likely a parallel process occurring with youth in our sample who described situations of dating and sexual aggression as drama, and one of the primary reasons for not engaging in bystander action. Thus, programming should acknowledge the dual role of drama in dating and sexual aggression situations and seek to understand student’s conceptualizations and perspective of drama to help identify ways in which they can intervene without increasing drama (for those who want to avoid it) and for those who are desiring of drama, empathy building activities may be especially important. Along these lines, experiential activities that help youth recognize the connections between “drama” and normalization of dating and sexual aggression could also be useful.

Another significant finding to emerge from our data is that students appear to have a conflicted relationship with social media in that they use it very frequently but also seem bothered by its problematic elements. As such, there seems to be an excellent opportunity to challenge the conventional uses of social media and make suggestions for using it in a more pro-social manner. For example, utilizing “callout” cards in situations of dating and sexual aggression from the That’s Not Cool campaign, which contain comical yet truthful messages that let peers and partners know they have crossed the line. Additionally, students are knowledgeable that abusive and harassing messages on sites such as Facebook and Twitter can have a direct, negative impact on their peers, but considering the potential consequences of such messages, instilling even higher levels of recognition and empathy are needed. Furthermore, youth report feeling immobilized on how to combat this negative messaging. As such, it may be helpful to use real cases examples that explore this issue (to build recognition and empathy) and pair it with specific exercises that allow for role playing different ways to help over social media (to help with skill building and confidence).

Furthermore, students indicated that youth tend to normalize dating and sexual aggression behaviors seen in the media and that this prevents youth from intervening or facilitates dating and sexual aggression perpetration. Given exposure to violent and sexualized media serves as a factor for dating and sexual aggression (Manganello 2008), media literacy programming can be used to help youth become better at identifying unhealthy relationships and to provide a platform for students to speak up about dating and sexual aggression to develop the skillset and language needed to be a prosocial bystander.

Although youth rarely provided examples of ways in which they intervene when dating and sexual aggression occur through social media, there were a number other situations in which youth described intervening. Many of these were very promising modes of intervention, such as verbally telling the perpetrator to stop or getting a teacher or adult. The wealth of language and examples of positive prosocial bystander action provided by youth can be used to tailor program content to it is salient and impactful. Finally, the identification of hotspots (i.e., school hallways, school cafeteria, school yard, buses, social media, and parties, both school dances and parties outside of school) suggests that it might be the most prudent for programming to specifically highlight through exercises and role plays these areas since they offer the most potential for dating and sexual aggression bystander action. Indeed, research suggests that hot spot mapping as a component of dating aggression prevention programming may be uniquely effective in reducing rates of dating aggression among youth (Taylor et al. 2013).

Finally, considerations need to be made in regard to the overall knowledge and developmental level of high school youth. In general, participants in this study showed higher levels of rape myth endorsement and less healthy attitudes towards dating violence than is normally seen in adult samples. Furthermore, while there were a number of encouraging responses in the focus group, there were also many instances of participants not understanding some basic concepts related to dating aggression, sexual harassment, and sexual aggression. Therefore, any bystander curriculum that is written for high school students must consider the level of general knowledge on this topic possessed by first-time participants. While many of the widely used college level bystander intervention programs are committed almost entirely to bystander-related topics, the findings of this study indicate that a high school level curriculum would benefit significantly from including more fundamental, background information on the topics of sexual and relationship aggression addressing the principles of positive bystander. As a result, effective high school programming may need to be longer in duration and more in-depth in regard to topic, than the current programs that are often used on college campuses and cited in the prevention literature.

Although these data provide important information on high school youths’ dating and sexual aggression bystander action, several limitations should be noted. First, the sample size was relatively small, especially for quantitative analyses, and non-diverse, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other samples. Thus, future research would benefit from using larger and more diverse samples. Also, we did not include a measure of social desirability, and the desire to respond in a socially desirable manner could have been something that impacted both survey results as well as focus groups results in the presence of peers. However, anecdotally, there was evidence in most focus groups of differing opinions among students. We also used single-item indices of dating and sexual aggression and had a limited assessment of correlates of bystander action. Thus, future research would benefit from more comprehensive measurements. Lastly, although we used one of the most commonly used measures of bystander action, it was developed initially for college students and some of the situations specific to high school youth may not be captured in the measure. In fact, based on the results of the qualitative findings and hot spots data, we intend to use findings form the current study in conjunction with other researchers to create a modified measure of bystander action (Bystander Measure Meeting, International Family Violence and Child Victimization Research Conference 2014).

Conclusion

Researchers are increasingly recognizing the critical importance of preventing dating and sexual aggression among youth (Reyes and Foshee 2013; Taylor et al. 2015; Vagi et al. 2013), and the critical role that bystander action plays in the prevention of such aggression (Noonan and Charles 2009). The current study sheds light on the situations in which youth have the most opportunity to intervene in situations of dating and sexual aggression, barriers (e.g., not knowing the victim) and facilitators (e.g., perceiving the victim may be injured or seriously hurt) of dating and sexual aggression bystander action, and both promising (e.g., notifying a parent or teacher) and problematic (e.g., use or threat of physical violence) ways of intervening in dating and sexual aggression situations. We hope that these data can be useful to researchers, practitioners, and educators in informing bystander prevention programming and evaluation efforts and ultimately contribute to the reduction of dating and sexual aggression among youth in our society.

Notes

At one of our participating schools, the vast majority of participants were White and our institutional review board urged us not to ask the racial identification question since this could make the data identifiable as opposed to anonymous. We thus used published data from the state’s department of education to represent the racial identification of the school where we could not collect this data directly from participants, and this data is included in the overall sample estimate above. Because we cannot connect the specific racial identification of each participant to their other data at this one school, we did not use racial identification in the inferential analyses as a correlate of dating and sexual aggression bystander action.

References

Banyard, V. L. (2008). Measurement and correlates of pro-social bystander behavior: The case of interpersonal violence. Violence and Victims, 23, 85–99. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.23.1.83.

Banyard, V. L. (2011). Who will help prevent sexual violence: Creating an ecological model of bystander intervention. Psychology of Violence, 1, 216–229. doi:10.1037/a0023739.

Banyard, V. L. (2013). Go big or go home: Reaching for a more integrated view of violence prevention. Psychology of Violence, 3, 115–120. doi:10.1037/a0032289.

Banyard, V. L., & Moynihan, M. M. (2011). Variation in bystander behavior related to sexual and intimate partner violence prevention: Correlates in a sample of college students. Psychology of Violence, 1, 287–301. doi:10.1037/a0023544.

Basile, K. C., Hamburger, M. E., Swahn, M. H., & Choi, C. (2013). Sexual violence perpetration by adolescents in dating versus same-sex peer relationships: Differences in associated risk and protective factors. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 14, 329–340. doi:10.5811/westjem.2013.3.15684.

Bennett, S., & Banyard, V. L. (2014). Do friends really help friends? The effect of relational factors and perceived severity on bystander perception of sexual violence. Psychology of Violence. doi:10.1037/a0037708.

Bennett, S., Banyard, V. L., & Garnhart, L. (2014). To act or not to act, that is the question? Barriers and facilitators of bystander intervention. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 476–496. doi:10.1177/0886260513505210.

Black, M. C., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Walters, M. L., Merrick, M. T., et al. (2011). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brown, A. L., Banyard, V. L., & Moynihan, M. M. (2014). College students as helpful bystanders against sexual violence: Gender, race, and year in college moderate the impact of perceived peer norms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38, 350–362. doi:10.1177/0361684314526855.

Burn, S. M. (2009). A situational model of sexual assault prevention through bystander intervention. Sex Roles, 60(11–12), 779–792. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9581-5.

Bystander Measure Meeting. (2014). University of New Hampshire’s International Family Violence and Child Victimization Research Conference, Durham NH.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Youth risk behavior survey. www.cdc.gov/yrbs.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Teen dating violence. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/teen_dating_violence.html.

Coker, A. L., Davis, K. E., Arias, I., Desai, S., Sanderson, M., Brandt, H. M., & Smith, P. H. (2002). Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23, 260–268. doi:10.1016/S0749-37970200514-7.

Dardis, C. M., Dixon, K. J., Edwards, K. M., & Turchik, J. A. (2014). An examination of the factors related to dating violence perpetration among young men and young women and associated theoretical explanations: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. doi:10.1177/1524838013517559.

de Bruijn, P., Burrie, I., & van Wel, F. (2006). A risky boundary: Unwanted sexual behaviour among youth. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 12, 81–96. doi:10.1080/13552600600841631.

Eckstein, R. P., Moynihan, M.M., Banyard, V. L., & Plante, E. (2013) Bringing in the bystander: Facilitator’s guide. http://cola.unh.edu/prevention-innovations/bringing-bystander.

Edwards, K. M., Mattingly, M. J., Dixon, K. J., & Banyard, V. L. (2014). Community matters: Intimate partner violence among rural young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53, 198–207. doi:10.1007/s10464-014-9633-7.

Edwards, K. M., Murphy, M. J., Tansill, E. C., Myrick, C. A., Probst, D. R., Corsa, R., & Gidycz, C. A. (2012). A qualitative analysis of college women’s leaving processes in abusive relationships. Journal of American College Health, 60, 204–210. doi:10.1080/07448481.2011.586387.

Edwards, K. M., Rodenhizer-Stämpfli, K., & Eckstein, R. P. (2015). Dating and sexual violence bystander intervention: A mixed methodological study of high school teachers. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Espeleage, D. L., Low, S. K., Anderson, C., & De La Ru, L. (2014). Bullying, dating and sexual aggression trajectories from early to late adolescence. National Institute of Justice report. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/246830.pdf.

Ferrans, S. D., Selman, R. L., & Feigenberg, L. F. (2012). Rules of the culture and personal needs: Witnesses’ decision-making processes to deal with situations of bullying in middle school. Harvard Educational Review, 82, 445–470.

Foshee, V. A., Bauman, K. E., Arriaga, X. B., Helms, R. W., Koch, G. G., & Linder, G. (1998). An evaluation of Safe Dates, an adolescent dating violence prevention program. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 45–50.

Foshee, V. A., Bauman, K. E., Ennett, S. T., Suchindran, C., Benefield, T., & Linder, G. F. (2005). Assessing the effects of the dating violence prevention program ‘Safe Dates’ using random coefficient regression modeling. Prevention Science, 6, 245–258. doi:10.1007/s11121-005-0007-0.

Foshee, V., Benefield, T., Ennett, S., Bauman, K., & Suchindran, C. (2004). Longitudinal predictors of serious physical and sexual dating violence victimization during adolescence. Preventive Medicine, 39, 1007–1016. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.014.

Foshee, V. A., & Langwick, S. (2010). Safe dates (2nd ed.). Center City, MN: Hazelden.

Frye, V. (2007). The informal social control of intimate partner violence against women: Exploring personal attitudes and perceived neighborhood social cohesion. Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 1001–1018. doi:10.1002/jcop.20209.

Frye, V., Galea, S., Tracy, M., Bucciarelli, A., Putnam, S., & Wilt, S. (2008). The role of neighborhood environment and risk of intimate partner femicide in a large urban area. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1473–1479. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.112813.

Furman, W., & Wehner, E. A. (1997). Adolescent romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. In S. Shulman & W. A. Collins (Eds.), Romantic relationships in adolescence: Developmental perspectives (pp. 21–36). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hamby, S., Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., & Ormrod, R. (2011). Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence and other family violence (NCJ232272). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

Hamby, S., & Grych, J. (2013). The web of violence: Exploring connections among different forms of interpersonal violence and abuse. New York, NY: Springer.

Jaffe, P. G., Sudermann, M., Reitzel, D., & Killip, S. M. (1992). An evaluation of a secondary school primary prevention program on violence in intimate relationships. Violence and Victims, 7, 129–146.

Koelsch, L. E., Brown, A. L., & Boisen, L. (2012). Bystander perceptions: Implications for University Sexual Assault Prevention Programs. Violence and Victims, 27, 563–579. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.27.4.563.

Lanza, S. T., & Collins, L. M. (2008). A new SAS procedure for latent transition analysis: Transitions in dating and sexual risk behavior. Developmental Psychology, 44, 446–456. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.446.

Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Latane, B., & Rodin, J. (1969). A lady in distress: Inhibiting effects of friends and strangers on bystander intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 5(2), 189–202.

Manganello, J. A. (2008). Teens, dating violence, and media use: A review of the literature and conceptual model for future research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 9(1), 3–18. doi:10.1177/1524838007309804.

Markiewicz, D., Lawford, H., Doyle, A., & Haggart, N. (2006). Developmental differences in adolescents’ and young adults’ use of mothers, fathers, best friends, and romantic partners to fulfill attachment needs. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 127–140. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-9014-5.

Marwick, A., & Boyd, D. (2014). ‘It's just drama’: Teen perspectives on conflict and aggression in a networked era. Journal of Youth Studies, 17, 1187–204. doi:10.1080/13676261.2014.901493.

McCauley, H. L., Tancredi, D. J., Silverman, J. G., Decker, M. R., Austin, S. B., McCormick, M. C., et al. (2013). Gender-equitable attitudes, bystander behavior, and recent abuse perpetration against heterosexual dating partners of male high school athletes. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 1882–1887. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301443.

McMahon, S. (2010). Rape myth beliefs and bystander attitudes among incoming college students. Journal of American College Health, 59, 3–11. doi:10.1080/07448481.2010.483715.

McMahon, S., & Farmer, G. L. (2011). An updated measure for assessing subtle rape myths. Social Work Research, 35, 71–81. doi:10.1093/swr/35.2.71.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Noonan, R., & Charles, D. (2009). Developing teen dating violence prevention strategies: Formative research with middle school youth. Violence Against Women, 15, 1087–1105. doi:10.1177/1077801209340761.

Norona, J. C., Thorne, A., Kerrick, M. R., Farwood, H. B., & Korobov, N. (2013). Patterns of intimacy and distancing as young women (and men) friends exchange stories of romantic relationships. Sex Roles, 68, 439–453. doi:10.1007/s11199-013-0262-7.

Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2010a). Active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: The role of personal characteristics and perceived peer pressure. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 815–827. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9399-9.

Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2010b). Why do bystanders of bullying help or not? Journal of Early Adolescence, 33, 315–340. doi:10.1177/0272431612440172.

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Vieno, A. (2012). The role of individual correlates and class norms in defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: A multilevel analysis. Child Development, 83, 1917–1931. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01831.x.

Reyes, H. M., & Foshee, V. A. (2013). Sexual dating aggression across grades 8 through 12: Timing and predictors of onset. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 581–595. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9864-6.

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukialnen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 1–15.

Taylor, Bruce G., Stein, Nan D., Mumford, Elizabeth A., & Woods, Daniel. (2013). Shifting boundaries: An experimental evaluation of a dating violence prevention program in middle schools. Prevention Science, 14, 64–76.

Taylor, K. A., Sullivan, T. N., & Farrell, A. D. (2015). Longitudinal relationships between individual and class norms supporting dating violence and perpetration of dating violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 745–760. doi:10.1007/s10964-014-0195-7.

Tjaden, P., & Thoennes, N. (2001). Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

Vagi, K. J., Rothman, E. F., Latzman, N. E., Tharp, A. T., Hall, D. M., & Breiding, M. J. (2013). Beyond correlates: A review of risk and protective factors for adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 633–649. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9907-7.

Van Camp, T., Hébert, M., Guidi, E., Lavoie, F., & Blais, M. (2014). Teens’ self-efficacy to deal with dating violence as victim, perpetrator or bystander. International Review of Victimology,. doi:10.1177/0269758014521741.

Weisz, A. N., & Black, B. M. (2008). Peer intervention in dating violence: Beliefs of African-American middle school adolescents. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 17, 177–196. doi:10.1080/15313200801947223.

Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B., Ruggiero, K. J., Danielson, C. K., Resnick, H. S., Hanson, R. F., Smith, D. W., et al. (2008). Prevalence and correlates of dating violence in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 755–762. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172ef5f.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sharyn Potter and Jane Stapleton for their feedback on the methodology of the study and Annie Crossman, Kayleigh Greaney, Amber Carlson, Joel Wyatt, and Kristin Lindemann for their assistance with data collection. We would also like to thank Eleanor MacKenzie, Saad Chowdry, Karen Brunetti, Chloe Flanagan, Kelly Palmer, Ashley MacPherson, Josh Dolman, and Nicholas Grafton who helped us with data entry and transcriptions. We would also like to thank Murray Straus, David Finkelhor, Lisa Jones, Heather Turner, Zeev Winstock, and Lars Alberth for their review and feedback on the article. Funding for this project provided collectively by the University of New Hampshire’s Prevention Innovations, Carsey Institute, and the College of Liberal Arts Dean’s Office.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Author contributions

KE conceptualized and developed the methodology for the study, participated in the collection of data, conducted qualitative and quantitative analyses, and drafted most sections of the manuscript. KR participated in the collection of data, managed data entry and transcription procedures, conducted qualitative analyses, and drafted some portions of the manuscript in addition to reading and editing multiple drafts of the manuscript. RE conceptualized and developed the methodology for the study, participated in the collection of data, provided feedback on the qualitative data analyses, and read and edited multiple drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Edwards, K.M., Rodenhizer-Stämpfli, K.A. & Eckstein, R.P. Bystander Action in Situations of Dating and Sexual Aggression: A Mixed Methodological Study of High School Youth. J Youth Adolescence 44, 2321–2336 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0307-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0307-z