Abstract

This study examined the role of pro-victim attitudes, personal responsibility, coping responses to observations of bullying, and perceived peer normative pressure in explaining defending the victim and passive bystanding behavior in bullying. A total of 462 Italian early adolescents (mean age = 13.4 years, SD = 9 months) participated in the study. The behaviors were measured through two informants: each individual student and the teachers. The findings of a series of hierarchical regressions showed that, regardless of the informant, problem solving coping strategies and perceived peer normative pressure for intervention were positively associated with active help towards a bullied peer and negatively related to passivity. In contrast, distancing strategies were positively associated with passive bystanding, whereas they were negatively associated with teacher-reported defending behavior. Moreover, self-reported defending behavior was positively associated with personal responsibility for intervention, but only under conditions of low perceived peer pressure. Finally, the perception of peer pressure for intervention buffered the negative influence of distancing on passive bystanding tendencies. Future directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

School bullying is a wide-spread phenomenon that has negative health (Gini and Pozzoli 2009) and psychosocial (Hawker and Boulton 2000) consequences for those directly involved. Most research in this area has studied bullying from an individual or a dyadic perspective, focusing mostly on the individual attributes that characterize bullies, victims, and bully/victims (e.g., Carlson and Cornell 2008; Gini 2008; Sijtsema et al. 2009). Although such research has provided important insights into the bullying dynamics, it has been limited by its focus on the aggressor-victim dyad. The present study aims at expanding the analysis of bullying to other roles that have been much less considered, namely the defender of the victim and the passive bystander. In particular, we analyze some possible correlates of defender’s and passive bystander’s behavior in an attempt to begin filling the lack of knowledge about these two roles.

The Peer Context in Which Bullying Occurs

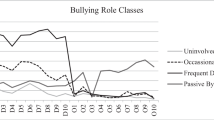

During the majority of bullying episodes, many students not directly involved as bullies or victims are present and witness them (Craig et al. 2000). The presence and reactions of this audience can influence how victims are perceived by peers and the students’ sense of safety at school (Gini et al. 2008b). According to the participant roles approach (Salmivalli et al. 1996b), most of these non-aggressive students assume different roles that are relevant to the bullying process. Some students take side with the victims and personally intervene to stop the bullying, defend and comfort the victimized schoolmate, or ask for teachers’ help. Others—the so-called passive bystanders or outsiders—withdraw from the scene, deny any bullying is going on, or remain as a silent audience (Cowie 2000).

Despite the increasing attention to the group dynamics underlying bullying, the current literature on the participant roles is still rather limited. In particular, there is a lack of empirical studies comparing the personal correlates of defenders and passive bystanders. We know that both of them are low in aggression and are able to avoid harassment for themselves (Camodeca and Goossens 2005). However, we still have too little information about «what makes some children to stick up for the victim or remain uninvolved, and also how their skills could be used in prosocial ways to combat bullying» (Andreou and Metallidou 2004, p.38).

To date, only a few studies have explicitly compared defenders and passive bystanders on some social-cognitive (e.g., social information processing, theory of mind), emotional (e.g., emotion regulation, empathy), and moral (e.g., moral disengagement) dimensions. In most cases, these studies did not report any statistically significant difference between the two roles on the measured dimensions (Andreou and Metallidou 2004; Camodeca and Goossens 2005; Gini 2006a; Gini et al. 2008a; Menesini et al. 2003). In a sample of Italian middle-school students, however, Gini et al. (2008a) found that defending the victim was associated with both high empathic responsiveness and high levels of social self-efficacy, whereas passive bystanding was associated with high empathy but low social self-efficacy. This result may suggest that, even though empathy is an important correlate of defenders’ prosocial behavior, it cannot be considered per se a sufficient condition, and that other variables (i.e., self-efficacy beliefs in the domain of interpersonal relationships) are important in favoring or limiting children’s helping behavior towards victimized peers. Another study (Menesini and Camodeca 2008) reported not-involved students—who can be considered similar to the passive bystanders—feeling less guilty or ashamed compared to defenders in hypothetical bullying scenarios. The authors commented on this result by hypothesizing that the outsiders may not «experience what Hoffman (2000) called ‘the moral conflict of innocent bystander’, according to which the one who witnesses someone in pain, danger or distress would experience the moral conflict of whether to help or not» (Menesini and Camodeca 2008, p.191). We may assume that this indifference leads them not to feel responsible for intervening and to remain outside.

Bystanding or Standing By?

In this study, we analyze possible intra-personal factors that might contribute to explain defending and passive bystanding behavior in middle-school students. For example, studies on attitudes towards bullying have reported that most students generally sympathize with the victims and disapprove of bullies (Rigby and Slee 1993). However, many of them are often reluctant to actively intervene or to inform adults (e.g., O’Connell et al. 1999). Moreover, positive attitudes towards victims have been shown to correlate positively with approval of students who intervened to stop bullying (Rigby and Slee 1993). Thus, we may hypothesize that such attitudes are also a significant correlate of active intervention in favor of the victim. Instead, negative attitudes towards victims may be related to passive bystanders’ lack of intervention.

However, attitudes are likely to be not sufficient to explain defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying. Children may perceive the victim’s suffering and believe that his/her condition is wrong, nevertheless, they may remain passively outside if they lack a sense of responsibility to intervene (Bandura 1991). Defenders’ behavior in bullying situations, in fact, is a particular type of prosocial behavior that may partly differ from more general altruistic conducts towards needy people in every-day life. Intervening in favor of the victim in the context of peer aggression represents a risky behavior, since the helper confronts a powerful bully and, sometimes, even his/her supporters. Given the particular conditions in which it occurs, intervention in favor of the victim of bullying should be regarded as a complex behavior that include not only the positive perception of the victim, but also a ‘moral’ assumption of personal responsibility to intervene from the defender. To our knowledge, the role of this personal responsibility in bullying has never been tested and no previous studies have identified personal responsibility as a possible characteristic distinguishing defenders from passive bystanders.

Finally, onlookers may fail to take responsible and supportive actions for other reasons, among which fear of becoming the target of the bullies or not possessing effective strategies to counteract bullying (Hazler 1996; Lodge and Frydenberg 2005). Again, the potentially difficult or dangerous nature of bullying situations renders active defending partially different from every-day prosocial behavior or problem-solving. For this reason, it is important to analyze specifically the role of coping responses to observations of bullying, rather than in other problematic situations. In the bullying literature, some studies have analyzed the coping strategies adopted by bullied children (Kristensen and Smith 2003; Salmivalli et al. 1996a; Smith et al. 2001). However, despite the importance of whether the audience respond to bullying has been demonstrated (Gini et al. 2008b), coping strategies adopted by uninvolved students when witnessing a peer being bullied have surprisingly received little attention. In other words, no previous studies have analyzed coping strategies of children who are in front of others’ negative life events (i.e., other peers’ being victimized) instead of personal events. In one study (Camodeca and Goossens 2005) students were asked to pretend they were witnessing an hypothetical bullying episode and to say what they would have done in that situation or which they thought were the best ways to cope with bullying. However, we still need to understand how bystanders actually respond to bullying suffered by other classmates (Lodge and Frydenberg 2005).

The first aim of this study, therefore, is to test whether defending and passive bystanding behaviors are differently explained by three intra-personal factors: (i) students’ attitudes towards victims, (ii) their sense of responsibility for intervention, and (iii) different coping responses to observations of bullying.

Perceived Normative Pressure from Peers

A further way to look at the ecological context in which bullying occurs is to analyze the social influence processes among classmates. Bullying behavior is sometimes approved by social norms that not necessarily reflect the private attitudes of most group members but nevertheless promote compliance within the group (Espelage et al. 2003; Gini 2006b, 2007; Juvonen and Galvan 2008). The analysis of how the perception of group norms and peer expectations shape the behavior of group members can be a means to understand mechanisms of peer influence. Despite the fact that the literature on such group influences has mainly focused on aggressive and antisocial behaviors, similar effects may be hypothesized when considering the behavior of students witnessing bullying. Even though observers do not necessarily join in bullying, the perceived expectations of others with whom one has a significant relationship might be associated with students’ active intervention or withdrawal.

Consistent with this idea, Rigby and Johnson (2006) recently found that believing that friends expected them to support the victims was among the most important predictors of students’ expressed intention to intervene. However, in that study, participants’ expressed willingness to intervene in front of an hypothetical bullying scenario rather than actual intervention in real bullying episodes was measured. Nonetheless, Rigby and Johnson’s results indicate that children’s reactions to bullying episodes may be affected by perceived normative pressure from the peer group.

Another aim of this study, therefore, is to test whether perceived peer normative pressure helps to explain actual defending and passive bystanding behavior above and beyond the other intra-individual characteristics of participants. It should be noted that we did not measure peer pressure as a second-level variable, that is at the class-level. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Brown et al. 1986; Griesler and Kandel 1998; Rigby and Johnson 2006), we conceptualize this variable as the individual’s perception of expectations from other classmates regarding the appropriate behavior during a bullying episode (e.g., “When a child is being bullied, according to my classmates I should intervene and help the victim”) and we hypothesize that such perception may add significantly to the explanation of students’ behavior.

The Present Study

To sum up, in this study we analyze possible correlates of defending and passive bystanding behavior that have never been considered in previous research. First, we investigate the role of students’ attitudes and we hypothesize that pro-victim attitudes are positively associated with participants’ defending behavior, whereas holding negative attitudes towards victims may lead students not to intervene. Second, we analyze participants’ sense of responsibility for intervention, hypothesizing that an high sense of personal responsibility is positively associated with students’ defending behavior. Conversely, it is hypothesized that low levels of such responsibility may lead students to remain aside as passive onlookers. Third, we analyze the coping responses in front of a peer being bullied associated with defending and passive bystanding behavior. Consistent with previous studies describing defenders as socially competent individuals (e.g., Gini et al. 2008a), we expect defending behavior to be associated with approach coping strategies, such as trying to solve the problem or seeking support from peers and adults. Conversely, we hypothesize that passive bystanding behavior is associated with avoidance strategies (i.e., distancing or internalizing).

Furthermore, we hypothesize that, above and beyond the aforementioned intra-personal factors, students’ perception of classmates’ expectation for active intervention in defense of a bullied peer, which represents the subjective perception of a social cue present in the peer context, may be an additional motivation for defending behavior. Thus, we predict that such perceived expectations are positively associated with defending behavior and negatively associated with passive bystanding behavior. Moreover, we test whether such perceived expectations moderated the association between the intra-personal characteristics and our dependent variables.

Beyond its direct effects, the perceived normative pressure from peers might also moderate the relations between the intra-personal characteristics and the participants’ behavior. For example, even if children think bullying is wrong or have an high sense of personal responsibility for intervention, they may be reluctant to actively intervene if they perceive passivity to be valued most among classmates. Conversely, a child with low personal responsibility might be motivated to defend the victim when such behavior is expected by others. Therefore, we test for the moderating role of perceived normative pressure in the relations of attitudes, sense of responsibility, and coping responses with defending and bystanding behavior.

Finally, girls tend to be higher than boys in defending behavior (Caravita et al. 2009; Gini et al. 2007; Salmivalli et al. 1996b), to show more positive attitudes towards victims (e.g., Rigby and Slee 1993) and to express more readiness to support the victims (Rigby and Johnson 2006). Moreover, previous studies have found that girls use more approach coping strategies (e.g., problem solving, seeking social support) than boys (Causey and Dubow 1992). Finally, gender differences in susceptibility to peer pressure have been reported (e.g., Prinstein and Dodge 2008). Therefore, we also test for the possible moderating role of gender, hypothesizing that (at least some of) the studied associations may be different for boys and girls. For example, we hypothesize that the associations between pro-victim attitudes and approach coping strategies, on the one hand, and defending behavior, on the other hand, are stronger in girls than in boys. Conversely, it is expected that the associations between perceived peer pressure and the outcome behavior are stronger in boys than in girls.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from four middle schools located in a midsize city in the north of Italy. All 7th and 8th grade students (N = 523) attending those schools were eligible to take part in this study. First, school principals and teachers were asked for consent. Then, parental consent letters were distributed to all the families in order to obtain their consent for their children’s participation. Finally, all the participants gave their personal assent for participation. Parents’ agreement reached 93% and none of the authorized students refused to participate. Subsequently, 22 children were excluded from the analysis because of reading comprehension difficulties, attention problems or missing data in their questionnaires. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 462 students (246 boys and 216 girls) from 22 classes. Socio-economic status was not directly measured. However, as in all public schools in Italy, our sample included students from a wide range of social classes (low- and working class through upper middle class). The mean age of the students was 13 years and 4 months (SD = 9 months). In terms of racial/ethnic background, 91.8% of the participants were Italian, 6.3% came from East Europe, 1.1% from Africa, 0.8% from South America.

Measures

Self-report of Behaviors in Bullying

Each of the three behaviors was measured by three items, with one item for each type of bullying (physical, verbal, relational). Items for bullying were: “I hit or push some of my classmates”, “I offend or give nasty nicknames to some of my classmates”, and “I exclude some classmates from the group or I spread rumors about them when they don’t hear me”. Items for defending were: “I defend the classmates who are hit or attacked hard”, “If someone teases or threatens a classmate, I try to stop him/her”, and “I try to help or comfort classmates who are isolated or excluded from the group”. Items for passive bystanding were: “When a classmate is hit or pushed, I stand by and I mind my own business”, “If a classmate is teased or threatened I do nothing and I don’t meddle”, and “If I know that someone is excluded or isolated from the group I act as if nothing had happened”. The items were derived from the Italian version (Menesini and Gini 2000) of the Participant Roles Questionnaire (Salmivalli et al. 1996b), which has been recently adapted and validated in self-report form for Italian students by Belacchi (2008). Participants were asked to rate how often (during the current school-year) they had enacted the behavior described in each item on a 4-point scale from 1 (never) to 4 (almost always).

A confirmatory factor analysis was performed with LISREL 8.54 program (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993) to test the three-factor structure of the questionnaire. Results revealed an adequate fit between the model and the data: χ 2(25) = 101.79, p < 0.05; goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = 0.95; adjusted-goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) = 0.91; non-normed-fit index (NNFI) = 0.91; root-mean-square residual (RMSR) = 0.04. Standardized loadings of the items on the bullying factor ranged from 0.48 to 0.79 (loading mean = 0.66), loadings on the defending factor ranged from 0.55 to 0.73 (loading mean = 0.66), and loadings on the passive bystanding factor ranged from 0.50 to 0.75 (loading mean = 0.63). According to Anderson and Gerbin (1988), item convergent validity was demonstrated because all the standardized loadings were significant at the p < 0.001 level, and all but one item exceeded the suggested item-to-total correlation threshold of 0.40, ranging from 0.37 to 0.57 (only students’ reports of indirect bullying were just below the threshold at 0.37). As suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981), internal consistency of the scales was measured through composite reliability (CR). For each participant, bullying (CR = 0.76), defending (CR = 0.75) and passive bystanding (CR = 0.76) scores were computed by averaging their answers in the three items of each subscale of the questionnaire.

Teacher-report of Behaviors in Bullying

The teacher-report questionnaire paralleled the self-report measure. Differences between the two instruments were only in the formulation in first or third person of verbal tenses. Also in this case, the three-factor structure was confirmed: χ 2(24) = 131.12, p < 0.05; GFI = 0.93; AGFI = 0.87; NNFI = 0.95; RMSR = 0.03. Standardized loadings of the items on the bullying factor ranged from 0.69 to 0.91 (loading mean = 0.77), loadings on the defending factor ranged from 0.86 to 0.92 (loading mean = 0.88), and loadings on the passive bystanding factor ranged from 0.83 to 0.90 (loading mean = 0.86), all significant at p < 0.001. Item-to-total correlations ranged from 0.63 to 0.85. For each participant we averaged the three items to form a bullying score (CR = 0.68), a defending score (CR = 0.69), and a passive bystanding score (CR = 0.70). The intercorrelations among the behaviors measured through the two informants are reported in Table 1.

Pro-victim Attitudes

Students’ attitudes towards bullying were measured through an adapted version of Salmivalli and Voeten’s (2004) scale, by asking the participants to evaluate the extent to which they agreed with ten statements about bullying (e.g., one should try to help the bullied victims; bullying may be fun sometimes, reverse coded). The level of agreement was expressed on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). A pro-victim attitude score was computed by averaging the students’ answers on the ten items (α = 0.80). The higher a student scored on the scale, the more his/her attitudes were in favor of the victim.

Coping Responses to Observations of Bullying

A modified version of the Self-Report Coping Measure (SRCM; Causey and Dubow 1992; Kristensen and Smith 2003) was used to assess coping responses to observations of bullying. The SRCM is a 34-item scale comprising five factor-analytically derived subscales: Seeking Social Support, Self-Reliance/Problem-Solving, Distancing, Internalizing, and Externalizing. In the original SRCM, children are asked how often they use each coping strategy in these two hypothetical situations: “When I get a bad grade in school, one worse than I normally get, I usually…” and “When I have an argument or a fight with a friend, I usually…”. The children answer the questions on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

For our research purpose and following Kristensen and Smith (2003), we changed the hypothetical situation as follows: “When in my classroom someone repeatedly bullies another classmate (insulting, hitting, threatening, damaging objects, spreading rumors or excluding from the group) I usually…”. Then, for each subscale of the SRCM, we selected the items that were appropriate for this situation. Only in few cases minor changes to the original items were needed (they are reported below in italics). The items selected were as follows: (a) Seeking Social Support (α = 0.80): “Tell a friend or family member what happened”, “Get help from a friend”, “Ask a friend for advice”, “Ask someone who has had this problem what I should do”, “Talk to the teacher about it”, “Ask a family member for advice”, “Get help from an adult in the school”; (b) Self-Reliance/Problem-Solving (α = 0.84): “Do something to make up for it”, “Try to understand why this happened”, “Try to think of different ways to solve it”, “Know there are things I can do to make it better”, “Try extra hard to keep this from happening again”, “Decide on one way to deal with the problem and I do it”, “Go over in my mind what to do or say”; (c) Distancing (α = 0.78): “Make believe nothing happened”, “Forget the whole thing”, “Do something to take my mind off of it”, “Tell myself it doesn’t matter”, “Refuse to think about it”, “Say I don’t care”; (d) Internalizing (α = 0.68): “Worry that others will think badly of me if I do something”, “Get mad at myself because I don’t know what I can do”, “Become so upset that I can say nothing”, “Worry too much about it”, “Cry about it”, “Just feel sorry and sad”. Items for externalizing coping strategies did not apply to the described situation and were not included. For each subscale the mean score was calculated for each participant.

Personal Responsibility

Participants’ sense of responsibility to intervene in favor of the victim was measured through four items: “Helping classmates who are repeatedly teased, hit or left out is my responsibility”, “In my classroom, if someone is surrounded by mindless gossip, pushed or threatened I don’t have to do anything” (reverse scored), “It is my responsibility to find a way so that in the classroom nobody is insulted, excluded or attacked”, “It’s not up to me doing something so that in my classroom nobody is repeatedly offended, pushed or leaved on one’s own” (reverse scored). Participants rated their agreement with each item on a 6-point scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). Answers to the four items were averaged to form a single personal responsibility score (α = 0.73).

Perceived Peer Normative Pressure

Perceived peers’ expectations regarding how the participant should behave when he/she witnesses bullying episodes was assessed. First, following Rigby and Johnson (2006), students were asked to read a brief introductory sentence: “If in my classroom someone repeatedly bullies another classmate, according to my classmates I should…”. Then, they rated to what extent peers expected them to behave in each of the following ways: (a) direct intervention (“…intervene to help the victim”), (b) ask for adults’ intervention (“…apprise an adult of what is happening so that he/she intervene”), (c) disregard (“…do nothing because it’s not my business”), (d) withdrawal for self-protection (“…do nothing because I could get into trouble”). Each rating was given on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Coding of answers to items (c) and (d) were reversed and the mean score on the four items was calculated (α = 0.69), so that a higher score represented a higher perceived peer pressure for intervention.

Procedure

The questionnaires were administered in group format by a research assistant during one full class period. Students were assured confidentiality and were told that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Participants were provided with the definition of bullying (see Gini 2006a; Olweus 1993). At the end of the session, children were thanked for their participation, debriefed about the purpose of the study and any question was answered. Teachers who had daily contact with students completed a questionnaire for each student rating children’s behavior during bullying episodes.

Results

Correlations Between Behavior in Bullying and the Other Study Variables

The correlations between each behavior and the other study variables are presented in Table 1. With regard to self-reports, defending behavior was positively correlated with all the study variables (0.21 < r < 0.56, all ps < 0.001), except with distancing, where a negative correlation emerged (r (461) = −0.27, p < 0.001). The same pattern of results, but with opposite signs, emerged from the correlation analysis between passive bystanding behavior and each of the study variable (−0.13 < r < −0.46, ps < 0.01).

As far as teacher-reports are concerned, defending behavior was negatively correlated with distancing (r (461) = −0.18, p < 0.001) and positively correlated with all the other study variables (0.10 < r < 0.18, ps < 0.05), except with internalizing. Passive bystanding behavior was negatively correlated with self-reliance/problem-solving (r (461) = −0.14, p = 0.002) and with perceived peer pressure (r (460) = −0.15, p = 0.002). Moreover, a positive correlation between distancing and passive bystanding behavior was found (r (461) = −0.17, p < 0.001).

Gender Differences on Study Variables

Descriptive statistics and gender differences are reported in Table 2. Effect sizes are expressed as Cohen’s d. As far as self-reported behavior are concerned, boys scored higher than girls in bullying and in passive bystanding behavior. Teachers rated girls higher than boys in defending behavior. Moreover, girls reported higher pro-victim attitudes than boys did. Girls also scored higher in seeking social support, in self-reliance/problem solving and in internalizing.

Regression Analyses Predicting Defending and Passive Bystanding Behavior

We conducted four hierarchical multiple regression analyses with defending or passive bystanding as the dependent variable. Separate analyses were conducted for self- and teacher-reports. The same procedure was used for all the regression analyses. A set of control measures—age, gender (0 = boys, 1 = girls) and bullying behavior—was entered in step 1. In step 2, intra-individual characteristics (pro-victim attitudes, personal responsibility and the four coping strategies) were entered. To test for the effect of perceived peer normative pressure, above and beyond the effects of the other predictors, this variable was entered in step 3. Finally, to test for possible moderation effects of gender and perceived peer normative pressure on the individual predictors, following Aiken and West’s (1991) guidelines, in step 4 we entered the interaction terms, that is the cross-products of gender and each individual characteristic, and of peer normative pressure and each individual characteristic. The interaction between gender and peer normative pressure was also entered. In order to decrease possible problems arising from multicollinearity and to facilitate interpretation of the results, all variables, except gender, were standardized (M = 0, SD = 1) and z scores were used to calculate the interaction terms (Aiken and West 1991).

Self-reported Defending Behavior

The model predicting defending behavior from control variables, individual characteristics, perceived peer normative pressure, as well as the interaction terms was significant (R 2 = 0.40, F (23, 436) = 12.90, p < 0.001).

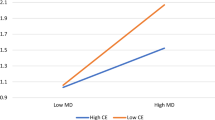

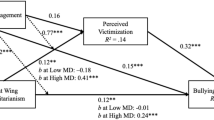

As can be seen in Table 3, gender, age and bullying behavior explained 2% (p = 0.02) of the variance of defending behavior. Only age and bullying behavior uniquely contributed to defending behavior (β = -0.10, p = 0.03, and β = -0.09, p = 0.04, respectively), so that younger age and lower levels of bullying predicted defending behavior. The individual predictors entered in the second step together accounted for a significant portion of the variance (33%, p < 0.001). In particular, self-reliance/problem-solving (β = 0.46, p < 0.001) and personal responsibility (β = 0.12, p = 0.009) significantly predicted defending behavior. Perceived peer pressure (β = 0.13, p = 0.002), entered in the third step, explained a further 1% of the variance (p = 0.002). Finally, the interaction terms explained an additional 4% of the variance (p = 0.006). Two interaction terms significantly predicted defending behavior: gender x internalizing (β = 0.18, p = 0.002) and perceived peer pressure × personal responsibility (β = −0.14, p = 0.009).

To interpret the nature of the interactions, ModGraph-I program (Jose 2008) was used. This program allowed both the graphical display of interactions and the interpretation of the figures through the simple slopes computations. Figure 1 depicts the interaction between gender and internalizing. Results derived from the simple slopes computation revealed that internalizing coping strategies were significantly related to different levels of defending behavior among girls (β = 0.16, SE = 0.05, p = 0.01), but not among boys (β = −0.10, SE = 0.06, ns).

To interpret the interaction between perceived peer pressure and personal responsibility, which involved continuous variables, simple slopes were derived for high (+1 SD), medium (0 SD), and low levels (−1 SD) of the moderator (Aiken and West 1991). Personal responsibility was significantly related to different amount of defending behavior at low levels of perceived peer pressure (β = 0.24, SE = 0.08, p = 0.003), but not at medium (β = 0.12, SE = 0.07, ns) and high levels (β = 0.00, SE = 0.08, ns) of the moderator (see Fig. 2).

Teacher-reported Defending Behavior

The model predicting defending behavior as evaluated by teachers from control variables, individual characteristics and perceived peer pressure was significant (R 2 = 0.13, F(10,448) = 6.82, p < 0.001). The results are reported in Table 3. The control variables entered in step 1 explained the 9% of the variance (p < 0.001). Teacher rated girls (β = 0.11, p = 0.02) and younger students (β = −0.10, p = 0.02) to be more prone to defend the victims of bullying. Moreover, higher bullying scores predicted lower defending behavior (β = −0.25, p < 0.001). Individual characteristics entered in step 2 accounted for an additional 3% of the variance (p = 0.03). In particular, the main effects of self-reliance/problem-solving and distancing were significant (β = 0.13, p = 0.03, and β = −0.10, p = 04, respectively). The beta weights indicate that higher levels of self-reliance/problem-solving and lower levels of distancing corresponded to higher levels of defending behavior. Consistent with the results on self-reported defending behavior, perceived peer pressure, entered in step 3, positively predicted defending behavior (β = 0.13, p = 0.009). None of the interaction terms (step 4) was significant.

Self-reported Passive Bystanding Behavior

Table 4 summarizes the results of the regression analysis on self-reported bystanding behavior. The overall model was significant (R 2 = 0.41, F(23, 436) = 13.17, p < 0.001).

The control measures entered in step 1 accounted for a significant portion of the variance of passive bystanding behavior (11%, p < 0.001). In particular, gender and bullying behavior emerged as significant predictors (β = −0.10, p = 0.02, and β = 0.31, p < 0.001, respectively), such that passive bystanding behavior was higher among boys and associated with higher bullying. With the entry of individual characteristics in step 2, there was a substantial and significant increase in the explained variance (22%, p < 0.001). Self-reliance/problem-solving and personal responsibility negatively predicted passive bystanding behavior (β = -0.24, p < 0.001, and β = −0.21, p < 0.001, respectively). In contrast, distancing was positively associated with this behavior (β = 0.18, p < 0.001). A further 5% of variance of passive bystanding behavior was explained by perceived peer pressure (β = −0.23, p < 0.001) entered in step 3. Finally, an additional 3% of explained variance (p = 0.03) was due to the significant interaction between perceived peer pressure and distancing coping strategies (β = −0.10, p = 0.03). This interaction is plotted in Fig. 3. As can be seen, perceived peer pressure operated as a buffer under conditions of high use of distancing coping strategies. Simple slopes computation showed that individual distancing coping strategies didn’t predict passive bystanding behavior for higher (β = 0.02, SE = 0.07, ns) and medium levels (β = 0.10, SE = 0.05, ns) of perceived peer pressure. In contrast, higher levels of distancing were related to higher levels of passive bystanding behavior for low levels of perceived peer pressure for intervention (β = 0.19, SE = 0.07, p = 0.008).

Teacher-reported Passive Bystanding Behavior

The model predicting teacher-reported bystanding behavior from control variables, individual characteristics and perceived peer pressure was significant (R 2 = 0.11, F(10, 448) = 5.25, p < 0.001).

The control variables entered in step 1 explained 6% of the variance. In particular, age (β = 0.11, p = 0.02) and bullying behavior (β = 0.20, p < 0.001) resulted positive predictors of passive bystanding behavior. When individual characteristics were entered in step 2, the R 2 increased to 0.9 (p = 0.009). Self-reliance/problem-solving (β = −0.15, p = 0.03) and distancing (β = 0.13, p = 0.02) emerged as significant predictors. Finally, perceived peer pressure (step 3) was significantly and negatively related to bystanding behavior (β = −0.12, p = 0.02), so that the higher the perceived pressure for intervention, the lower the students’ tendency to behave as passive bystanders. None of the interactions (step 4) was significant above and beyond the main effects (see Table 4).

Discussion

This study was among the first to analyze the possible correlates of early adolescents’ defending and passive bystanding behavior, namely pro-victim attitudes, personal responsibility for intervention and coping strategies adopted as witnesses of bullying episodes. Moreover, the role of perceived peer normative pressure in onlookers’ behavior was analyzed. Participants’ defending and passive bystanding behavior was measured through two informants: the students themselves and their teachers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to employ both self- and teacher-reports to evaluate defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying.

Self- and Teacher-reported Defending and Passive Bystanding Behaviors

Even though this was not a specific aim of the study, it is worth mentioning that the magnitude of the correlations between the behavior assessed through the two informants fell within the 0.10–0.30 range, indicating modest agreement. This result is consistent with previous studies about aggression, bullying and victimization showing low to moderate levels of agreement between different informants (e.g., Pellegrini and Bartini 2000). In our case, agreement between the individual child and the teacher was probably even more difficult due to the ‘out of sight’ nature of some behaviors (e.g., acting as if nothing wrong is happening), which might be less visible to people outside the peer-group.

Certainly, each informant has strengths and biases; however several authors claimed that the lack of consistency between different sources should not be taken as an index of poor reliability of the single method used, since this discrepancy may account for the real complexity of the phenomenon under study (Crick 1996; Schneider 2000). This suggests that different sources be used in the same study rather than a single procedure, because they complement each other in measuring behaviors in bullying and provide different perspectives on the problem. Following solicitations not to rely on self-reports only, the use of the two informants is a strength of the current study. The fact that the size of the effects was higher with self-reported behavior may be partly explained by a ‘shared method variance’ effect, which was not a problem with teacher-reports. On the other hand, the fact that, with few exceptions, the regression analyses yielded similar results, regardless of the informant, strengthens our findings, which cannot be viewed as a mere artifact of the self-report methodology.

Individual Characteristics Associated with Defending and Passive Bystanding Behavior

Consistent with recent studies (e.g., Gini et al. 2008a; Menesini and Camodeca 2008), our findings showed that defending and passive bystanding behaviors are associated with either different characteristics or the same characteristics but in the opposite direction. First, with regard to our control variables, older and more aggressive children were less likely to intervene in favor of the victim of bullying and more likely to remain passively aside. This is consistent with studies reporting bullying and passivity being perceived as two associated and negative sides of the phenomenon (Cowie 2000; Gini et al. 2008b). Only for teachers, girls were significantly more likely to defend than were boys.

Second, above and beyond the effects of age, gender, and active bullying, both self- and teacher-rated defending behavior were positively predicted by the self-reliance/problem-solving coping strategy that, in contrast, was negatively associated with passive bystanding. Consistent with our hypothesis, passive bystanding was also predicted by high levels of distancing (i.e., forget the whole thing, tell myself it doesn’t matter), regardless of the informant. In sum, as reported by other studies (Causey and Dubow 1992; Kristensen and Smith 2003), defending the victim of bullying is a socially competent behavior associated with approach, problem-focused strategies adopted when observing bullying suffered by a peer. Conversely, our results confirmed passivity to be related with the tendency to distance oneself from the victim’s negative experience.

Moreover, in contrast with our hypothesis, the internalizing coping strategy did not predict per se our outcome variables, while gender moderated the association between internalizing and self-reported defending behavior, so that high levels of internalizing were positively related to defending behavior among girls but not among boys. The meaning of this result is not clear, since internalizing is usually conceptualized as an avoidance strategy (Causey and Dubow 1992), and it should be taken cautiously. In interpreting it, we should bear in mind that, contrary to previous studies, we examined students’ coping strategies for dealing with witnessing bullying suffered by others, not with being bullied. We may speculate that, in these particular circumstances, when children are in front of others’ negative life events instead of personal events, the negative emotions provoked by that event and reflected by the internalizing coping items (e.g., feeling sorry and sad, being upset) may represent a sort of compassion for the victim’s distress, promoting intervention instead of avoidance. Given that this was the first study analyzing onlookers’, instead of victims’, coping strategies, these findings might not be directly comparable with the broader literature on coping strategies and deserve further exploration in future studies.

Third, consistent with our hypothesis, active help was significantly associated with personal responsibility for intervention. Conversely, low levels of such responsibility were associated with passivity. These results, however, did emerge only for self-reported behaviors and clearly need to be replicated in future studies. Nonetheless, albeit preliminary, these findings seem to confirm that active intervention in favor of a peer who is being bullied at school is linked to some kind of ‘moral’ assumption of responsibility (Menesini and Camodeca 2008), while processes of diffusion or displacement of responsibility might lead to passivity (Bandura 1991).

Finally, pro-victim attitudes positively correlated with defending behavior and negatively correlated with passive bystanding behavior. However, when they were entered together with the other independent variables in the regression analyses, pro-victim attitudes did not significantly predict our outcome variables. Of course, lack of significant results may be due to various reasons. However, taken together with the results described above, we may hypothesize that defending a bullied peer is a risky and socially complex behavior that cannot simply develop from positive attitudes towards the victim. If confirmed in future longitudinal studies this result might have important implications for anti-bullying interventions, indicating that simply changing students’ attitudes may not necessarily increase their active helping behavior towards bullied peers.

The Role of Perceived Peer Pressure for Intervention

Another aim of the current study was to test whether perceiving that classmates expected active intervention in favor of a bullied peer would be associated with participants’ helping behavior. Our findings show that, regardless of the informant, defending behavior was positively predicted by the perceived peer pressure for intervention, above and beyond the effects of the other individual characteristics. In contrast, participants’ perception of classmates’ expectation for intervention was negatively associated with passive bystanding behavior. This result is consistent with our hypothesis and significantly expands previous findings (Rigby and Johnson 2006) by demonstrating the associations between perceived peer pressure within the class and students’ actual behavior, rather than mere intention to intervene. Moreover, this result found with middle-school students is consistent with the broader literature on peer (formal and informal) groups, which shows that peers’ influence, for example in terms of adherence to group norms, becomes particularly relevant during early adolescence (e.g., Bukowski et al. 1996; Juvonen and Galvan 2008). However, since within the class-group the normative pressure from friends can differ from the normative pressure from non-friends, in future studies different sources of influence should be analyzed.

Results on self-reported behaviors also pointed out that perceived peer normative pressure moderated the association between personal responsibility and behavior. High levels of perceived peer pressure were positively associated with defending behavior regardless of the level of personal responsibility for intervention. That is, even students’ with low personal responsibility tend to defend the bullied peer when they believe that other classmates expect such prosocial behavior from them. In contrast, when the perception of pressure for intervention from classmates is low, the positive relation between personal responsibility and defending behavior becomes evident. Consistent with a child by environment approach (Ladd 2003), this result may be regarded as an example of how intra-individual variables and social cues present in the peer context, in the form of perceived peer pressure, interact in explaining behavior in bullying during the middle-school years. Since in this study we measured individual students’ perception of peer pressure, future studies should deepen the analysis of these processes by analyzing group-level variables (such as, peer group norms or attitudes), in order to better understand under which contextual conditions defending behavior can emerge as a likely behavior.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us to describe causal pathways in the relations between our study variables and participants’ behaviors in bullying. For example, while coping strategies are likely to influence students’ behavior, frequent experience with helping behavior might help them to develop more adequate strategies of intervention in bullying situations. To overcome this limitation, longitudinal studies are required. Second, we did not collect information about participants’ experiences of victimization, that is, we did not know whether and how often they had been bullied in their life. Future studies should test the possible relations between personal experiences of victimization from peers and the type of reaction enacted in front of another peer being bullied. Moreover, onlookers responses to bullying might vary according to whom is being bullied (e.g., a same vs. opposite sex peer, a friend vs. an acquaintance). Therefore, future research should compare defending and passive bystanding under different contextual conditions. Finally, we should be cautious when comparing the current findings with previous works that assessed defending and bystanding through peer nominations; further studies replicating this research through different sources of information (e.g. peers, parents) and analyzing other individual and contextual correlates of the two participant roles are solicited.

Within these limitations, this study was the first to provide data examining the association between defending and passive bystanding behavior and different correlates using a multi-informant approach. While the majority of studies in this field tend to rely only on self-report data, thus suffering from problems of shared method variance, we tested our hypothesized relations with data collected through two different informants. As commented above, the fact that the regression analyses based on the two informants yielded fairly similar results, strengthens our findings. Moreover, since teachers spend a lot of time with students, and often play a role in signaling bullying problems and in implementing anti-bullying strategies in their school, the analysis of bystanders’ behavior and characteristics from teachers’ point of view may help us to better understand this multifaceted phenomenon. Future studies should explore more extensively teachers’ ability to reliably detect bystanders’ behavior and compare teachers’ perspective with both self-reports and the perception of peers.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbin, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Andreou, E., & Metallidou, P. (2004). The relationship of academic and social cognition to behavior in bullying situations among Greek primary school children. Educational Psychology, 24, 27–41.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In W. M. Kurtines & J. L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development (Vol. 1, pp. 45–103). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Belacchi, C. (2008). I ruoli dei partecipanti nel bullismo: una nuova proposta [Participants Roles in bullying: a new proposal]. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia, 4, 885–912.

Brown, B. B., Clasen, D. R., & Eicher, S. A. (1986). Perceptions of peer pressure, peer conformity dispositions, and self-reported behavior among adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 22, 521–530.

Bukowski, W., Newcomb, A., & Hartup, W. (1996). The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Camodeca, M., & Goossens, F. A. (2005). Children’s opinions on effective strategies to cope with bullying: the importance of bullying role and perspective. Educational Research, 47, 93–105.

Caravita, S. C. S., Di Blasio, P., & Salmivalli, C. (2009). Unique and interactive effects of empathy and social status on involvement in bullying. Social Development, 18, 140–163.

Carlson, I. W., & Cornell, D. G. (2008). Differences between persistent and desistent middle school bullies. School Psychology International, 29, 442–451.

Causey, D. L., & Dubow, E. F. (1992). Development of a self-report coping measure for elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21, 47–59.

Cowie, H. (2000). Bystanding or standing by: gender issues in coping with bullying in English schools. Aggressive Behavior, 26, 85–97.

Craig, W. M., Pepler, D. J., & Atlas, R. (2000). Observations of bullying in the playground and in the classroom. School Psychology International, 21, 22–36.

Crick, N. R. (1996). The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children’s future social adjustment. Child Development, 67, 2317–2327.

Espelage, D. L., Holt, M. K., & Henkel, R. R. (2003). Examination of peer-group contextual effects on aggression during early adolescence. Child Development, 74, 205–220.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variable and measurement error: algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 382–388.

Gini, G. (2006a). Social cognition and moral cognition in bullying: what’s wrong? Aggressive Behavior, 32, 528–539.

Gini, G. (2006b). Bullying as a social process: the role of group membership in students’ perception of inter-group aggression at school. Journal of School Psychology, 44, 51–65.

Gini, G. (2007). Who is blameworthy? Social identity and inter-group bullying. School Psychology International, 28, 77–89.

Gini, G. (2008). Associations between bullying, psychosomatic symptoms, emotional and behavioral problems. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 44, 492–497.

Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2009). Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 123, 1059–1065.

Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoè, G. (2007). Does empathy predict adolescents’ bullying and defending behavior? Aggressive Behavior, 33, 467–476.

Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoè, G. (2008a). Determinants of adolescents’ active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 93–105.

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., Borghi, F., & Franzoni, L. (2008b). The role of bystanders in students’ perception of bullying and sense of safety. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 617–638.

Griesler, P. C., & Kandel, D. B. (1998). Ethnic differences in correlates of adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health, 23, 167–180.

Hawker, D. S., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 41, 441–455.

Hazler, R. (1996). Bystanders: an overlooked factor in peer on peer abuse. The Journal for the Professional Counsellor, 11, 11–21.

Hoffman, M. L. (2000). Empathy and moral development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jöreskog, K. A., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural equation modelling with the SIMPLIS command language. Chicago: Scientific Software.

Jose, P. E. (2008). ModGraph-I: A programme to compute cell means for the graphical display of moderational analyses: The internet version, Version 2.0. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington.

Juvonen, J., & Galvan, A. (2008). Peer influence in involuntary social groups: Lessons from research on bullying. In M. J. Prinstein & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents (pp. 225–244). New York: Guilford.

Kristensen, S. M., & Smith, P. K. (2003). The use of coping strategies by Danish children classed as bullies, victims, bully/victims, and not involved, in response to different (hypothetical) types of bullying. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 44, 479–488.

Ladd, G. W. (2003). Probing the adaptive significance of children’s behavior and relationships in the school context: A child-by-environment perspective. In R. Kail (Ed.), Advances in child behavior and development (pp. 43–104). New York: Wiley.

Lodge, J., & Frydenberg, E. (2005). The role of peer bystanders in school bullying: positive steps towards promoting peaceful schools. Theory into Practice, 44, 329–336.

Menesini, E., & Camodeca, M. (2008). Shame and guilt as behaviour regulators: relationships with bullying, victimization and prosocial behaviour. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 26, 183–196.

Menesini, E., & Gini, G. (2000). Il bullismo come processo di gruppo: adattamento e validazione del questionario “Ruoli dei partecipanti” alla popolazione italiana [Bullying as a group process: Adaptation and validation of the Participant Role Questionnaire to the Italian population]. Età Evolutiva, 66, 18–32.

Menesini, E., Sanchez, V., Fonzi, A., Ortega, R., Costabile, A., & Lo Feudo, G. (2003). Moral emotions and bullying: a cross-national comparison of differences between bullies, victims and outsiders. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 515–530.

O’Connell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: insights and challenges for intervention. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 437–452.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school. What we know and what we can do. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Pellegrini, A. D., & Bartini, M. (2000). An empirical comparison of methods of sampling aggression and victimization in school settings. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(2), 360–366.

Prinstein, M. J., & Dodge, K. A. (2008). Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents. New York: The Guilford Press.

Rigby, K., & Johnson, B. (2006). Expressed readiness of Australian schoolchildren to act as bystanders in support of children who are being bullied. Educational Psychology, 26, 425–440.

Rigby, K., & Slee, P. T. (1993). Dimensions of interpersonal relation among Australian children and implications for psychological well-being. Journal of Social Psychology, 133, 33–43.

Salmivalli, C., & Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviors associated with bullying in schools. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 246–258.

Salmivalli, C., Karhunen, J., & Lagerspetz, K. M. J. (1996a). How do the victims respond to bullying? Aggressive Behavior, 22, 99–109.

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996b). Bullying as a group process: participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 1–15.

Schneider, B. H. (2000). Friends and enemies: Peer relations in childhood. London: Arnold.

Sijtsema, J. J., Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., & Salmivalli, C. (2009). Empirical test of bullies’ status goals: assessing direct goals, aggression, and prestige. Aggressive Behavior, 35, 57–67.

Smith, P. K., Shu, S., & Madsen, K. (2001). Characteristics of victims of school bullying: Developmental changes in coping strategies and skills. In S. Graham & J. Juvonen (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 332–351). New York: Guilford.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G. Active Defending and Passive Bystanding Behavior in Bullying: The Role of Personal Characteristics and Perceived Peer Pressure. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38, 815–827 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9399-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9399-9