Abstract

There are several lines of evidence that suggest religiosity and spirituality are protective factors for both physical and mental health, but the association with obesity is less clear. This study examined the associations between dimensions of religiosity and spirituality (religious attendance, daily spirituality, and private prayer), health behaviors and weight among African Americans in central Mississippi. Jackson Heart Study participants with complete data on religious attendance, private prayer, daily spirituality, caloric intake, physical activity, depression, and social support (n = 2,378) were included. Height, weight, and waist circumference were measured. We observed no significant association between religiosity, spirituality, and weight. The relationship between religiosity/spirituality and obesity was not moderated by demographic variables, psychosocial variables, or health behaviors. However, greater religiosity and spirituality were related to lower energy intake, less alcohol use, and less likelihood of lifetime smoking. Although religious participation and spirituality were not cross-sectionally related to weight among African Americans, religiosity and spirituality might promote certain health behaviors. The association between religion and spirituality and weight gain deserves further investigation in studies with a longitudinal study design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Much research supports religiosity and spirituality as protective factors for both physical and mental health, and postulated mechanisms for this relationship include healthier lifestyles, greater social support, and improved psychological and biochemical factors (e.g., Ellison and Levin 1998; Koenig 1999, 2001; Koenig et al. 1999; Larson et al. 1992; Roff et al. 2005; Strawbridge et al. 1997). The association between religiosity/spirituality and obesity is less clear. On the one hand, religiosity and spirituality have been associated with improved health outcomes, which might suggest that religiosity would reduce the incidence of obesity. Involvement in religious groups with religious doctrines of healthy living may be associated with lower rates of obesity through the promotion of health behaviors such as decreased alcohol intake and increased physical activity (Kim et al. 2003; Strawbridge et al. 1997). Healthy coping behaviors and stress reduction practices afforded through religious involvement may also help in reducing obesity risk. On the other hand, reduced rates of smoking among religious attendees might inadvertently lead to higher obesity rates as, for example, smoking has been shown to be an appetite suppressant (Jo et al. 2002) and smokers tend to weigh less than non-smokers (Cline and Ferraro 2006).

Associations between religiosity, spirituality, and obesity are particularly important to understand among African Americans, for whom religion, spirituality, and fellowship in church communities have been viewed as particularly salient (Carter 2002). In the United States, African Americans have higher rates of obesity and associated comorbidities than other ethnic groups (Cossrow and Falkner 2004). Cultural patterns that include community fellowship surrounding eating and reported tendencies to eat foods high in fat (Airhihenbuwa et al. 1996) may contribute to increased rates of obesity in African Americans, but the current findings are inconsistent. Some religious social settings may encourage less healthy eating and lead to weight gain for African Americans, but these potential relationships are poorly understood. A few studies have observed religious attendance to be associated with increased body weight (Feinstein et al. 2010; Ferraro 1998; Lapane et al. 1997), and some studies indicate that religiosity is associated with increased body weight for certain groups (e.g., African American women) but not others (Bruce et al. 2007). Two studies observed no association between religiosity and obesity (Ellis and Biglione 2000; Roff et al. 2005). Other lines of evidence suggest that the association between religion/spirituality and obesity is mediated by smoking status (e.g., Kim et al. 2003). Although some of these studies have included African Americans, most have not focused on African American populations.

Feinstein et al. (2010) recently investigated the associations between religiosity, spirituality, and obesity in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) cohort, a large, ethnically diverse sample of adults. Participants with higher religious attendance, private prayer, and daily spirituality were more likely to be obese and less likely to smoke than their less religious counterparts, even after controlling for smoking status and other potential confounders. Feinstein et al. (2010), however, did not investigate race as a potential moderating factor, and thus, it is possible that relationships between religiosity/spirituality and obesity differ for African Americans versus other ethnic groups. More research is needed to clarify the associations between religiosity/spirituality and obesity among African Americans, particularly in geographic areas where religious communities may be even more salient (e.g., the southeastern United States).

We examined the association between multiple dimensions of religiosity and spirituality with weight among a large sample of African Americans, subgroup differences, and potential mechanisms. In order to elucidate possible mechanisms, we planned to examine whether demographic characteristics, health behaviors, or psychosocial variables mediated any of the observed associations between religiosity/spirituality and obesity.

Method

Study Population

The Jackson Heart Study (JHS) is a longitudinal population-based observational cohort study designed to prospectively investigate the novel determinants of cardiovascular disease in African Americans (Taylor et al. 2005). A total of 5,301 ambulatory African American men and women (63.4% female, age range 21–94 years, mean age 55) in the Jackson, MS metropolitan statistical area (MSA; Hinds, Madison, Rankin Counties) were recruited between September 2000 and March 2004. Approximately 31% of the cohort were participants from the Jackson, MS site of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Others were randomly selected residents and volunteers who matched defined demographic cells in proportions designed to mirror those in the overall African American population in the Jackson MSA. The final portion of the cohort consisted of family members. Full details of the recruitment protocol are described elsewhere (Fuqua et al. 2005). Interviews and clinical examinations were conducted by trained research staff. The JHS was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Jackson State University, Tougaloo College, and the University of Mississippi Medical Center, and participants gave written informed consent.

Weight Measures

Body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) were used as markers of obesity. Standing height and weight were measured in light clothing and without shoes in accordance with standard protocols. BMI was defined as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). WC was measured at the umbilicus and without constricting garments using an anthropometric tape and rounded to the nearest centimeter.

BMI weight status was defined as follows: normal weight: BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2; overweight: BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2; obesity: BMI 30–39.9 kg/m2; and morbid obesity: BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2. Abdominal obesity was defined as WC > 88 cm for women and >102 cm for men.

Religiosity and Spirituality

Dimensions of religiosity and spirituality included organized religious activity, private prayer, and daily spiritual experiences. Organized religious activity was defined as church attendance or involvement in other forms of organized religion such as watching services on TV or participating in Bible study groups. Participants indicated the frequency of these activities as not at all, less than once a year, a few times a year, a few times a month, at least once a week, or nearly every day. These responses were coded from 1 to 6, respectively, with higher scores indicating more frequent attendance. Private religious experience was assessed as reported frequency of prayer or meditation outside of formal religious activity (rated as never, less than once a month, once a month, a few times a month, once a week, a few times a week, once a day, or more than once a day). This item was coded from 1 to 8, respectively, with higher scores indicating more frequent private prayer. The Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES; Underwood and Teresi 2002) assessed daily spiritual experiences in six domains, including feeling God’s presence, feeling God’s love, and being spiritually touched by creation, and has been shown to have good psychometric properties in the JHS (Loustalot et al. 2006). Participants were asked to rate the frequency of these experiences from “never” to “many times a day,” coded as 1–5, respectively, and summed. The DSES score ranged from 5 to 30 with higher scores indicating higher spirituality. Of the JHS participants who completed the baseline examination, 3,968 had complete religiosity and spirituality information. The Cronbach’s alpha for the DSES in this sample was 0.83.

Demographic Variables

Education was measured as the highest level of schooling completed and classified into six categories: less than high school; high school diploma or graduate equivalency degree; vocational training or some college; associate’s degree; bachelor’s degree; and post-graduate degree. Income was self-reported into 11 categories ranging from under $5,000 to $100,000 or more and categorized into four categories based on the poverty level for the appropriate family size as defined by the concurrent US Census year of the JHS participant’s clinic examination. Low income was defined as a total household income to family size ratio below the poverty level. The middle-income categories were separated into lower-middle and upper-middle, respectively, as a ratio of 2.5 times the poverty level. High income was defined as a per capita income ratio of more than four times the poverty level threshold.

Health Behavior Variables

Dietary Intake

Dietary information was ascertained using the 158-item Delta Nutrition Intervention Research Initiative Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ; Tucker et al. 2005). This FFQ was adapted from a longer, 283-item FFQ developed (Carithers et al. 2005) and validated (Carithers et al. 2009; Talegawkar et al. 2008) for use in adults living in the Mississippi area. Daily energy intake and percentage of dietary fat were calculated from contributions of each of the 158 food items in the FFQ.

Physical Activity

Trained JHS interviewers asked participants standard physical activity (PA) questions using the JHS Physical Activity Cohort Survey (PAC) (Dubbert et al. 2005). The JHS PAC consists of 30 items regarding PA in four different domains: active living; work; sports; and home and family life, with domain-specific values ranging from 1 to 5, and has been validated against accelerometer and pedometer data (Smitherman et al. 2009). A total PA score was calculated as the sum of the four individual index scores with higher scores indicating more activity (range 4–20).

Smoking Status

Current cigarette smoking was defined as a positive response to “Have you smoked more than 400 cigarettes in your lifetime?” and “Do you now smoke cigarettes?” Former cigarette smoking was defined as a positive response to the first question and a negative response to the latter question.

Alcohol Intake

Alcohol intake was assessed with standard questions used in the ARIC Study and the Third National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES-3; National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1994); participants were classified as lifetime abstainers, ever users, and users during the last 12 months.

Psychosocial Variables

Social Support

A modified 16-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL; Cohen and Hoberman 1983) scale was used to measure the functional aspects of positive social support. The ISEL assesses perceived availability of four different types of social support: tangible (material resources), belonging (people to socialize with), self-esteem (positive social comparisons), and appraisal (people to discuss problems/difficulties with). Adequate psychometric properties of this modified scale have been demonstrated previously in the JHS (Payne et al. 2005). The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the entire JHS cohort was 0.83.

Depression

Frequency of depressive symptoms during the preceding week was measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977). The CES-D was developed for use in large epidemiologic studies and has been shown to have excellent psychometric properties, including in African American samples (Radloff 1977; Naughton and Shumaker 2003). Individual items were scored from 0 to 3 (depending on the item), and the total depressive symptoms scale ranged from 0 to 60. The Cronbach’s alpha for the CES-D for the entire JHS cohort was 0.82.

Statistical Analysis

Only participants with complete information on religious attendance, private prayer, and daily spirituality measures; health behaviors (daily energy intake, physical activity, smoking status, and alcohol intake); and psychosocial measures (depression and social support) were included in the current study. Of the 3,968 participants with complete religiosity and spirituality measures, a total of 1,590 were excluded (missing health behavior information: n = 340, missing psychosocial measures: n = 1,250), leaving 2,378 participants for analysis.

Sample characteristics were compared by sex and across categories of religiosity and spirituality using proportions and chi-square tests for categorical variables and means (SD) and t tests for continuous variables. The statistical significance of linear trends across religiosity and spirituality categories was assessed by including these variables as ordinal covariates (i.e., coded as 1–4) in unadjusted regression models.

The independent association between religiosity/spirituality and obesity was assessed using hierarchical multivariable linear regression. BMI and WC were entered as continuous dependent variables in order to examine the relationships between religiosity and the full continuum of body weight. Models were built in stages: religiosity/spirituality (in separate models), age and sex were entered on Step 1, and education level and income status were entered on Step 2. Health behaviors (smoking status, physical activity, caloric intake, percent of calories from fat, and alcohol use) were entered on Step 3. Psychosocial factors (social support and depression) were entered on Step 4.

Next, we examined whether demographic characteristics, health behaviors, or psychosocial variables moderated the association between religiosity/spirituality and obesity using a series of sequential hierarchical multivariable linear/logistic regression models. The test of moderation examines whether one variable (the “moderator”) affects the direction and/or strength of the relationship between the independent variable (religiosity/spirituality) and the dependent variable (obesity; Baron and Kenny 1986). In Step 1, age, gender, education, income, and smoking status were entered. Religious attendance, private prayer, daily spirituality, and the moderator to be tested were entered in Step 2. Interaction terms to test for interactions between each of the three religiosity/spirituality variables and each potential moderator were entered in Step 3.

Finally, we examined whether any of the demographic characteristics, health behaviors, or psychosocial variables mediated any of the observed associations between religiosity/spirituality and obesity.

Due to the large number of analyses, the alpha level for significance was set at 0.001 for all analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics 18. In all regression analyses, data were examined for adherence to assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity, and outliers greater than 3.3 standard deviations from their predicted mean were removed, as suggested by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007).

Results

The 2,387 participants included in these analyses did not differ substantially on obesity measures from the other JHS participants but had reported more involvement in religious activities and private spirituality (ps < 0.001, Table 1). In addition, participants included in these analyses were more likely to be female, report lower SES, engage in less physical activity and report lower social support than the rest of the JHS cohort (ps < 0.001, Table 1). As shown in Table 1, the majority of these differences were quite small and would not be considered clinically significant.

Our analytic sample consisted of 811 men and 1,567 women, with a mean age of 53.6 years. Compared with women, men were less obese, but had higher WC, and reported lower religious attendance, private prayer, and daily spirituality (ps < 0.001, Table 2).

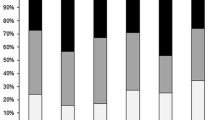

Participants with more frequent organized religious activity tended to be older, were more likely to be female, and reported consuming fewer calories, less alcohol use, less smoking, lower depressive symptoms, and higher social support (Table 3). Similar trends were observed across categories of private prayer (Table 4) and daily spirituality (data not shown). In unadjusted analyses, there were trends for individuals who attend religious services a few times per year or less to have higher WCs than those who attend a few times per month (p = .02; Table 3) and for participants who report praying more than once per day to have higher BMIs than those who pray once per day (p = .03; Table 4).

In hierarchical regression analyses, organized religious activity, private prayer, and daily spiritual experiences were not associated with BMI or WC (Table 5). To test for possible non-linear relationships between religiosity/spirituality, analyses were repeated using analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) in which independent variables were categorical religiosity and spirituality variables (each in quartiles as in Tables 3, 4), dependent variables were BMI and WC, and covariates were age, sex, education, and income. Similarly, these categorical analyses indicated no significant associations between religiosity/spirituality and obesity. Because separate models of religious attendance, private prayer, and daily spirituality revealed identical results, the combined model is shown in Table 5.

There was no evidence of moderation by demographic characteristics, health behaviors, or psychosocial variables on the association between religiosity/spirituality variables and obesity (Table 5). Since no significant associations were observed between religiosity, spirituality, and obesity, mediational analyses were not conducted.

Discussion

This study examined whether multiple dimensions of religiosity and spirituality were associated with obesity in a large cohort of African Americans in the southeastern US. Although some studies have included African Americans, few were exclusively African American. Our findings suggest that religiosity and spirituality are not reliably related to obesity indicators in this population. The association between religiosity and spirituality variables and obesity also did not appear to be moderated by demographics, psychosocial variables, or health behaviors. We did find positive associations between religiosity, spirituality, and health behaviors: participants who reported praying more often did report consuming fewer calories per day; attendance, prayer, and daily spiritual experiences were each related to less likelihood of self-reported alcohol use in the past year; and participants who attended church more often were less likely to report a lifetime history of smoking. Religious attendance, private prayer, and daily spirituality were also each related to several indices of improved psychosocial functioning (e.g., lower depression and higher social support).

Our results were consistent with studies that have indicated no relationship between religiosity, spirituality, and body weight (Ellis and Biglione 2000; Gillum 2006; Roff et al. 2005). Notably, the study by Roff et al. utilized a sample in the southeastern United States, as in the present study. Our results confirm Roff et al.’s findings that although religiosity and spirituality may be related to some health behaviors, they are not related to body weight per se. The present study extends these results to a large African American sample in the southeastern United States, as Roff and colleagues’ sample included African Americans and Caucasians. Our sample also allows the examination of intraracial differences.

In contrast to some previous studies that have suggested that religion and spirituality may increase the risk of overweight or obesity (Feinstein et al. 2010; Ferraro 1998; Lapane et al. 1997), our findings suggest that this is not the case in the current sample. Why this might be the case is unclear. One possibility is that the positive relationships between religion and body weight found in large multiethnic samples (e.g., Feinstein et al. 2010) do not apply to African Americans. Our discrepant results could also be explained by differences in demographics other than race. For example, in Feinstein and colleagues’ study using MESA data, the sample tended to be older and less predominantly female (mean age = 63; 52% female) than the present sample (mean age = 54; 66% female). However, neither age nor sex emerged as moderating factors in our study.

One alternative explanation is that a relationship between religiosity, spirituality, and body weight did not emerge because of a restricted range of religiosity and body weight. The majority of our participants reported high levels of religious attendance, prayer, and daily spirituality and also tended to have higher BMIs. These characteristics are quite common among African Americans in Mississippi, and thus, our sample appears representative of our target population. Indeed, Feinstein et al. (2010) noted that African Americans tend to report higher levels of religiosity and spirituality than other ethnic groups. The lack of a relationship between religiosity, spirituality, and body weight could be due to a restricted range of both of these variables in the current sample. Despite the lack of relationship between religiosity variables and body weight, associations did emerge between religiosity/spirituality and health behaviors (i.e., self-reported caloric intake, alcohol use, and smoking).

Although our results suggesting a lack of relationship between religiosity, spirituality, and obesity are in contrast with other studies suggesting an association, the current findings regarding health behavior are generally consistent with extant research. For example, several studies suggest a lower lifetime history of smoking among more religious individuals (Feinstein et al. 2010; Lapane et al. 1997; Roff et al. 2005). Obisesan et al. (2006) found some evidence of healthier eating associated with religion: among African American women in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, weekly religious attendance was associated with fish intake at least once weekly. However, religious attendance was not related to caloric intake in that particular study.

Recent research has focused on implementing weight loss interventions for African Americans in church settings (Kim et al. 2008). Given that religious participation and private spirituality predict some health behaviors (i.e., reduced caloric intake, less alcohol, and tobacco use) among African Americans, religious settings are a potentially important venue for health behavior education in this population.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study has several limitations. We cannot conclude that any aspect of religion causes changes in health behaviors because of the cross-sectional nature of our study; we can only indicate the associations between these variables. Future research in this area should include longitudinal studies that would at least help to clarify the temporal relationships between religiosity, health behavior, and body weight.

A notable limitation of the current study is the extent of missing data on self-report measures (particularly for religiosity, spirituality, and depressive symptoms). Despite extensive follow-up to facilitate the return of questionnaire booklets containing these measures, response rates remained less than ideal, though not unexpected given the already extensive time required for in-person data collection. Fortunately, the resulting sample size (n = 2,378) is still quite large, and participants with complete versus missing data did not differ in BMI or obesity status. The differences that were detected between included and excluded participants (i.e., religiosity, spirituality, physical activity, and social support) were small in magnitude and not considered clinically significant. The issue of missing data does present the possibility of selection bias; perhaps results would differ for the subset of excluded participants who tend to be less religious. However, the levels of religiosity and spirituality reported in this sample appear consistent with other studies of African Americans (e.g., Feinstein et al. 2010). An additional limitation is that because a social desirability measure was not administered, there is the possibility for social desirability bias.

Although results suggest that religious participation might promote health behavior in this African American sample, we must note that this study employed self-reported measures of caloric intake, alcohol use, and smoking. It is possible that church attenders are less likely to report their “sinful” eating, drinking, or smoking habits. Participants’ under-reporting of caloric intake or alcohol use could potentially explain why church attenders report lower caloric intake yet do not show differences in body weight. However, the present study is strengthened by some objective measures (e.g., BMI and waist circumference). Future research should include more objective measures, such as biochemical measures of smoking, pedometer data indicating physical activity, and objective records of church attendance.

Information on participants’ religious denominations was not collected in the JHS. Future research should assess the relationships between religion, body weight, and health as a function of different religions and religions dominations. Finally, our results may only apply to African Americans living in the southeastern United States. Future studies should assess the relationships between religion, body weight, and health in different regions of the United States, as well as in different countries.

Despite these limitations, the present study is strengthened by a large sample size, the assessment of multidimensional aspects of religion (organized religious participation, private prayer, and daily spiritual experiences), and statistical analyses controlling for important variables related to body weight and health (e.g., smoking status, income, and education level). We also tested whether the relationships between religion and health were moderated by age, sex, education level, income status, and smoking status. We found no relationships between religion and obesity in any demographic subgroups within this population.

Our results suggest that in a large sample of African Americans living in the southeastern United States, religious attendance, private prayer, and daily spirituality are not related to body weight when demographic variables are statistically controlled. However, certain religiosity and spirituality variables are related to lower self-reported caloric consumption, alcohol use, and lifetime history of smoking. Future research should continue to investigate the relationships between religion and health among African Americans, as well as potential mediators of these relationships. We hope that this area of research will lead to tailored health behavior interventions for African Americans to reduce health disparities in this population.

References

Airhihenbuwa, C. O., Kumanyika, S., Agurs, T. D., Lowe, A., Saunders, D., & Morssink, C. B. (1996). Cultural aspects of African American eating patterns. Ethnicity and Health, 1, 245–260.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6, 1173–1182.

Bruce, M. A., Sims, M., Miller, S., Elliott, V., & Ladipo, M. (2007). One size fits all? Race, gender and body mass index among US adults. Journal of the National Medical Association, 99, 1152–1158.

Carithers, T., Dubbert, P. M., Crook, E., Davy, B., Wyatt, S. B., Bogle, M. L., et al. (2005). Dietary assessment in African Americans: Methods used in the Jackson Heart Study. Ethnicity and Disease, 15(Suppl 6), S6-49–S6-55.

Carithers, T. C., Talegawkar, S. A., Rowser, M. L., Henry, O. R., Dubbert, P. M., Bogle, M. L., et al. (2009). Validity and calibration of food frequency questionnaires used with African-American adults in the Jackson Heart Study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109, 1184–1193.

Carter, J. H. (2002). Religion/spirituality in African American culture: An essential aspect of psychiatric care. Journal of the National Medical Association, 94, 371–375.

Cline, K. C. M., & Ferraro, K. F. (2006). Does religion increase the prevalence and incidence of obesity in adulthood? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45, 269–281.

Cohen, S., & Hoberman, H. (1983). Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13, 99–125.

Cossrow, N., & Falkner, B. (2004). Race/ethnic issues in obesity and obesity-related comorbidities. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 89, 2590–2594.

Dubbert, P. M., Carithers, T., Ainsworth, B. E., Taylor, H. A. Jr., Wilson, J. G., & Wyatt, S. B. (2005). Physical activity assessment methods in the Jackson Heart Study. Ethnicity and Disease, 15(Suppl 6), S6-56–S6-61.

Ellis, L., & Biglione, D. (2000). Religiosity and obesity” Are overweight people more religious? Personality and Individual Differences, 28, 1119–1123.

Ellison, C. G. & Levin, J. S. (1998). The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education and Behavior, 25, 700–720. 93–103.

Feinstein, M., Liu, K., Ning, H., Fitchett, G., & Lloyd-Jones, D. M. (2010). Burden of cardiovascular risk factors, subclinical atherosclerosis, and incident cardiovascular events across dimensions of religiosity: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation, 121, 659–666.

Ferraro, K. F. (1998). Firm believers? Religion, body weight, and well being. Review of Religious Research, 39, 222–244.

Fuqua, S. R., Wyatt, S. B., Andrew, M. E., Sarpong, D. F., Henderson, F. R., Cunningham, M. F., et al. (2005) Recruiting African American research participation in the Jackson Heart Study: Methods, response rates, and sample description. Ethnicity and Disease, 15(Suppl 6), S6-18–S6-29.

Gillum, R. F. (2006). Frequency of attendance at religious services, overweight, and obesity in American women and men: The third national health and nutrition examination survey. Annals of Epidemiology, 16, 655–660.

Jo, Y., Talmage, D. A., & Role, L. W. (2002). Nicotinic receptor-mediated effects on appetite and food intake. Journal of Neurobiology, 53, 618–632.

Kim, K. H., Sobal, J., & Wethington, E. (2003). Religion and body weight. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 27, 469–477.

Kim, K. H., Linnan, L., Campbell, M. K., Brooks, C., Koenig, H. G., & Wiesen, C. (2008). The WORD (wholeness, oneness, righteousness, deliverance): A faith-based weight-loss program utilizing a community-based participatory research approach. Health Education and Behavior, 35, 634–650.

Koenig, H. G. (1999). The healing power of faith. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Koenig, H. G. (2001). Religion and medicine III: Developing a theoretical model. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 31, 199–216.

Koenig, H. G., Hays, J. C., Larson, D. B., George, L. K., Cohen, H. J., McCullough, M. E., et al. (1999). Does religious attendance prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3968 older adults. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 54, M370–M376.

Lapane, K. L., Lasater, T. M., Allan, C., & Carleton, R. A. (1997). Religion and cardiovascular disease risk. Journal of Religion and Health, 36, 155–163.

Larson, D. B., Sherrill, K. A., Lyons, J. S., Craigie, F. C., Jr., Thielman, S. B., Greenwold, M. A., et al. (1992). Associations between dimensions of religious commitment and mental health reported in the American Journal of Psychiatry and Archives of General Psychiatry: 1978–1989. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 557–559.

Loustalot, F. V., Wyatt, S. B., Boss, B., & McDyess, T. (2006). Psychometric examination of the daily spiritual experiences scale. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 13, 162–167.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. (1994). Plan and operation of the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–1994: Series 1: Programs and collection procedures. Vital Health Statistics I, 32, 1–407.

Naughton, M. J., & Shumaker, S. A. (2003). The case for domains of function in quality of life assessment. Quality of Life Research, 12(suppl 1), 73–80.

Obisesan, T., Livingston, I., Trulear, H. D., & Gillum, F. (2006). Frequency of attendance at religious services, cardiovascular disease, metabolic risk factors, and dietary intake in Americans: An age-stratified exploratory analysis. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 36, 435–448.

Payne, T. J., Wyatt, S. B., Mosley, T. H., Dubbert, P. M., Guiterrez-Mohammed, M. L., Calvin, R. L., et al. (2005). Sociocultural methods in the Jackson Heart Study: Conceptual and descriptive overview. Ethnicity and Disease, 15(Suppl 6), S6-38–S6-48.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Roff, L. L., Klemmack, D. L., Parker, M., Koenig, H. G., Sawyer-Baker, P., & Allman, R. M. (2005). Religiosity, smoking, exercise, and obesity among southern, community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 24, 337–354.

Smitherman, T. A., Dubbert, P. M., Grothe, K. B., Sung, J. H., Kendzor, D. E., Reis, J. P., et al. (2009). Validation of the Jackson Heart Study physical activity survey in African Americans. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 6, S124–S132.

Strawbridge, W. J., Cohen, R. D., Shema, S. J., & Kaplan, G. A. (1997). Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 957–961.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th Ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Talegawkar, S. A., Johnson, E. J., Carithers, T. C., Taylor, H. A., Bogle, M. L., & Tucker, K. L. (2008). Carotenoid intakes, assessed by food-frequency questionnaires (FFQs), are associated with serum carotenoid concentrations in the Jackson Heart Study: Validation of the Jackson Heart Study Delta NIRI adult FFQs. Public Health and Nutrition, 11, 989–997.

Tucker, K., Maras, J., Champagne, C., Connell, C., Goolsby, S., Weber, J., et al. (2005). Development of a regional food frequency questionnaire for the US Mississippi Delta. Public Health Nutrition, 8, 87–96.

Underwood, L., & Teresi, J. (2002). The daily spiritual experience scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 22–23.

Taylor, H. A., Jr, Wilson, J. G., Jones, D. W., Sarpong, D. F., Srinvasan, A., Garrison, R. J., et al. (2005). Toward resolution of cardiovascular health disparities in African Americans: design and methods of the Jackson Heart Study. Ethnicity and Disease, 15(Suppl 6), S-64–S-617.

Acknowledgments

This research from the Jackson Heart Study is supported by NIH contracts N01-HC-95170, N01-HC-95171, and N01-HC-95172 provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reeves, R.R., Adams, C.E., Dubbert, P.M. et al. Are Religiosity and Spirituality Associated with Obesity Among African Americans in the Southeastern United States (the Jackson Heart Study)?. J Relig Health 51, 32–48 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9552-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9552-y