Abstract

Religiosity has been associated with greater body weight. Less is known about South Asian religions and associations with weight. Cross-sectional analysis of the MASALA study (n = 906). We examined associations between religious affiliation and overweight/obesity after controlling for age, sex, years lived in the USA, marital status, education, insurance status, health status, and smoking. We determined whether traditional cultural beliefs, physical activity, and dietary pattern mediated this association. The mean BMI was 26 kg/m2. Religious affiliation was associated with overweight/obesity for Hindus (OR 2.12; 95 % CI: 1.16, 3.89), Sikhs (OR 4.23; 95 % CI: 1.72, 10.38), and Muslims (OR 2.79; 95 % CI: 1.14, 6.80) compared with no religious affiliation. Traditional cultural beliefs (7 %), dietary pattern (1 %), and physical activity (1 %) mediated 9 % of the relationship. Interventions designed to promote healthy lifestyle changes to reduce the burden of overweight/obesity among South Asians need to be culturally and religiously tailored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

South Asians are one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the USA and over 90 % are foreign-born (U. S. Census Bureau 2012; Barnes et al. 2008). Compared to other racial/ethnic groups, South Asians have greater risk of obesity-related conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease (Joshi et al. 2007; Holland et al. 2011; Karter et al. 2013; Moran et al. 2014). Physical inactivity, diets low in fruits and vegetables, and central adiposity are believed to contribute to this disparity (Joshi et al. 2007; Ye et al. 2009; Fernandez et al. 2011; Daniel and Wilbur 2011; Ghai et al. 2012; Misra and Khurana 2011).

Similar to other immigrant groups, South Asians may be involved in cultural and religious activities that revolve around traditional norms, such as participation in customary religious services (Fekete and Williams 2012; Pollard et al. 2003; Basch et al. 1994; Kim 1987; Zhou 1992; Mukherjea et al. 2013). Religiosity among diverse racial/ethnic groups, such as Whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Chinese Americans, has been associated with greater body weight or overweight/obesity (Feinstein et al. 2010, 2012; Gillum 2006). In a prior study, religiosity was positively associated with being overweight/obese among South Asian immigrants in the USA, but no diet or physical activity data were available to explain this association (Bharmal N 2013).

Different religious affiliations within the heterogeneous South Asian community may affect smoking, alcohol use, and dietary practices differentially because of lifestyle prescriptions specific to each religion (Eliasi et al. 2002). For example, Hinduism prescribes vegetarianism, Islam prohibits alcohol or pork ingestion, and Sikhism strongly prohibits tobacco use (Eliasi et al. 2002; Jonnalagadda and Diwan 2002; Raymond and Sukhwant 1990). As immigrants increase their exposure to Western cultural practices, they may adopt the less healthy food choices found in their host country (Akresh 2007; Batis et al. 2011; Guendelman et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2007; Lv and Cason 2004). For South Asians, this may mean reduced intake of plant foods and home-cooked meals that may increase risk of overweight/obesity and related conditions (Raj et al. 1999; Karim et al. 1986; Garduno-Diaz and Khokhar 2013).

Using data from the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) study which included measures of diet, physical activity, and strength of traditional cultural beliefs, our objective was to examine the associations between religious affiliations and overweight or obese BMI among a religiously heterogeneous group of South Asians.

Methods

Participants

The MASALA study is a community-based cohort investigating the prevalence and associations of cardiovascular risk factors and subclinical atherosclerosis in a population-based sample of South Asian men and women age 40–84 years (Kanaya et al. 2013). The MASALA study is the first prospective cohort of US South Asians and was modeled on the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) to allow for efficient and valid cross-ethnic comparisons (Bild et al. 2002). We enrolled 906 South Asians, free of CVD at baseline, from two geographical regions between October 2010 and March 2013.

Data Collection

Measurements obtained at baseline included (but not limited to) sociodemographics, lifestyle factors, anthropometric measurements, oral glucose tolerance testing, brachial blood pressure, and blood samples for biochemical risk factors. Participants self-reported religious affiliation with Hinduism, Sikhism, Islam, Jainism, Christianity, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, or none. We classified participants who reported Buddhism and Zoroastrianism as “Other” (n = 6) and those who reported more than one affiliation as “Multiple” (n = 15).

BMI was calculated from measured weight and height (Kanaya et al. 2013). Three observations for which BMI was missing were dropped. In multivariate analysis, BMI was dichotomized using Asian BMI cut-offs as healthy (BMI < 23 kg/m2) or overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2) (World Health Organization expert consultation 2004; Jih et al. 2014). We included seven respondents categorized as underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) in the healthy BMI category. Waist and hip circumference were measured using a flexible tape according to a standardized protocol by certified staff. We defined South Asian abdominal obesity as obese waist circumference as ≥80 cm in women and ≥90 cm in men (Alberti et al. 2006) and calculated the waist-to-hip ratio.

We included sociodemographic characteristics, healthcare access, health status, years lived in the USA, strength of traditional cultural beliefs, diet, and physical activity as covariates in our analysis. Sociodemographics included age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, and income. Health status was gauged by self-reported health status, which has been shown to be associated with mortality in multiethnic populations (McGee et al. 1999) and cigarette smoking status. Health insurance status was used as a proxy for healthcare access. We calculated percentage of lifetime in the USA from years lived in the USA divided by the respondent’s current age. Percentage of lifetime in the USA may be a better temporal measure than years lived in the USA because the former may better quantify the proportion of lifetime exposure to American cultural practices. Among the 19 US-born respondents, we used current age for years lived in the USA.

Using data from prior qualitative work in Asian Indians (Mukherjea et al. 2013), we created a traditional cultural beliefs scale consisting of seven items. The base question was “How much would you wish these traditions from South Asia would be practiced in America?” The seven items included: performing religious ceremonies; serving sweets at ceremonies; fasting on specific occasions; living in a joint family; having an arranged marriage; eating a staple diet of chapatis, rice, dal, vegetable, and yogurt; and using spices for health and healing. The items were scored on a Likert scale with higher scores representing weaker traditional Indian beliefs. We analyzed tertiles of the score (<12 for strongest, 12–17 for moderate, and ≥17 representing weakest traditional beliefs). The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the current study sample was 0.83 with similar reliability in both men and women.

Diet was assessed through an in-person food group intake using the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic Groups (SHARE) South Asian Food Frequency Questionnaire, which was developed and validated in South Asians in Canada, and included items unique to the South Asian diet (Kelemen et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2010). With principal component analysis, we have identified three distinctive dietary patterns; each respondent was assigned a factor score for each dietary pattern identified (Gadgil et al. 2014). The three major dietary patterns observed, named after the components with the highest factor loadings in each pattern, were: animal protein (positive for alcohol, coffee, eggs, fish, pasta, pizza, poultry, red meat, refined grains, vegetable oil; negative for whole grain, low-fat dairy, legumes); fried snacks, sweets and high-fat dairy (positive for added fat, butter/ghee, fried snacks, fruit juice, high-fat dairy, sugar-sweetened beverages, legumes, potatoes, refined grains, rice, snacks, sweets, whole grains; negative for vegetable oil and nuts); and fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes (positive for fruit, fruit juice, legumes, low-fat dairy, vegetable oil, nuts, vegetables, whole grains). Physical activity was assessed using the Typical Week’s Physical Activity Questionnaire (Ainsworth et al. 2011) and reported as MET-minutes of physical activity per week. The “metabolic equivalent of task” (MET) is a ratio widely accepted as a replicable measure of the intensity level of a specific form of physical activity.

Analysis

We describe the prevalence of baseline characteristics in the total sample. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to estimate the odds of being classified as overweight/obese as a function of religious affiliation, adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, healthcare access, health status, and percentage of lifetime in the USA in Model 1 (n = 903). Model 2 was additionally adjusted for intensity of traditional cultural beliefs, dietary pattern, and physical activity (n = 888). We dichotomized marital status, educational level, health status, and healthcare insurance status. Age, percentage of lifetime in the USA, and exercise MET-min per week were examined as continuous and categorical variables in the model. While income was not included in the final model (n = 26 missing observations), our results with or without income were similar. Missing and refused observations were dropped from our multivariate analyses. In all models, we used “None” or no religious affiliation as the reference category.

Multivariable models were also stratified by strength of traditional cultural beliefs (weak, moderate, strong). We tested for sex-specific interactions with religious affiliation and none were found. We conducted mediation analysis using the Karlson/Holm/Breen logit regression tests to determine whether traditional cultural beliefs, dietary pattern, physical activity, smoking status, immigrant status (US-born or foreign-born), and/or educational attainment mediated the relationship between religious affiliation and overweight/obese BMI (Karlson and Holm 2011). We tested for sex- and age-specific interactions and none were found. The analysis was completed using STATA/SE (version 12.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

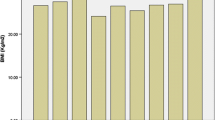

The mean age of South Asians in the MASALA cohort was 55 years; most of the sample was married, well educated, and insured (Table 1). A significant percentage of respondents had high cholesterol (46 %), hypertension (41 %), and/or diabetes (25 %). On average, half of respondents’ lives were spent in the USA. The majority of respondents were affiliated with Hinduism, followed by Sikhism, Islam, Jainism, Christianity, other (Buddhism or Zoroastrianism), and multiple religions. Fifty-eight respondents reported no religious affiliation (6.4 %). The age-adjusted mean BMI was 26 kg/m2, which did not differ by sex. Seventy-six percent of the sample was overweight/obese. Hindus had a mean BMI of 25.8 kg/m2, Sikhs 27.2 kg/m2, Muslims 26.7 kg/m2, Jains 25.6 kg/m2, Christians 26.4 kg/m2, other 22.9 kg/m2, multiple religions 28.4 kg/m2, and no religious affiliation 26.1 kg/m2. The figure shows the BMI categories by each religious affiliation (Fig. 1).

In the multivariable analysis, Hindus had 2.12 greater odds of being overweight/obese than respondents with no religious affiliation (95 % CI: 1.16, 3.89; Table 2). This higher odds was also observed for Sikhs (OR 4.23, 95 % CI: 1.72, 10.38) and Muslims (OR 2.78, 95 % CI:1.14, 6.80) compared with those with no religious affiliation in Model 1. We found no significant associations for Jains, Christians, other or multiple religious affiliation respondents. When we additionally adjusted for traditional cultural values, physical activity, and dietary pattern in Model 2, we found similar increased likelihood for being overweight/obese among Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims. The addition of macronutrients or substitution of dietary pattern with macronutrients did not meaningfully change the results. Percentage of lifetime in the USA was not significantly associated with BMI in adjusted models.

In order to understand whether traditional cultural beliefs moderated the relationship between religious affiliation and overweight/obese BMI, we stratified Model 2 by traditional cultural belief score (weak, moderate, or strong). We found that among those with weak traditional beliefs, Hindus (OR 2.34), Sikhs (OR 9.17), and Jains (OR 6.44) were significantly more likely to be overweight/obese than those with no religious affiliation (p < 0.05). No such effect of religious affiliation was found in stratified models of South Asians with strong or moderate cultural beliefs.

Traditional cultural beliefs, dietary pattern, and physical activity were examined as mediators of the relationship between religious affiliation and overweight/obesity. The proportion of the total effect explained by these three variables in the mediation was 8.9 %; traditional cultural beliefs contributed 6.9 %, while dietary pattern and physical activity contributed 1.1 % each. Smoking status, educational attainment, and immigrant status were not significant mediators.

Discussion

Risk of overweight/obese BMI was higher among respondents who affiliated with Hinduism, Sikhism, and Islam compared to those with no religious affiliation. We found minimal mediation in the relationship between religious affiliation and overweight/obesity by traditional cultural beliefs, dietary pattern, and physical activity. Adherence to traditional cultural beliefs, which included questions on diet and religious participation, may provide a deeper understanding of why religious affiliation may impact obesity risk in this population.

Our findings are somewhat consistent with a study that found highly religious South Asian Hindus and Sikhs were more likely to be overweight/obese than those who were less religious (Bharmal N 2013). In contrast to that study, we also found a significant association of being overweight/obese among Muslim South Asian immigrants living in the US. Religion and religiosity have been linked to increased body mass index in other non-South Asian populations (Feinstein et al. 2010; Gillum 2006; Cline and Ferraro 2006; Ferraro 1998; Lapane et al. 1997; Kim et al. 2003).

We found that a proxy measure of acculturation, as measured by percentage of lifetime in the USA, was not associated with risk for overweight/obesity. This finding is consistent with some studies that did not find an association between years in the USA or English proficiency with obesity (Bharmal N 2013; Nguyen et al. 2014), though other studies have found a positive association with BMI among Asian American immigrants (Chen et al. 2012; Lauderdale and Rathouz 2000) Dietary acculturation, or the adoption of Western dietary practices, has been observed among immigrants, and one study among Canadian South Asian immigrants found that length of residence was associated with increased consumption of fruits and vegetables and improvement in food preparation (i.e., grilling vs. deep frying), but also increased consumption of convenience foods, red meat, sugar-sweetened beverages, and eating out (Lesser et al. 2014). In the MASALA sample, recent South Asian immigrants (<20 years of residence in the USA) were more likely to be categorized as following a fried snacks, sweets and high-fat dairy diet or fruits and vegetables dietary pattern in comparison with long-term resident respondents who were more likely to follow a Western dietary pattern (Gadgil et al. 2014). Those with stronger traditional cultural beliefs or limited English proficiency were also more likely to adhere to the sweets and refined grains dietary pattern.

Religious practices around diet, physical activity, and tobacco use may possibly explain risk of increased BMI among Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims compared to those with no religious affiliation. For example, gatherings centered on religious and/or cultural ceremonies for South Asian immigrants may involve consumption of foods high in refined sugar or saturated fat (Mukherjea et al. 2013; Jonnalagadda and Diwan 2002; Deedwania and Singh 2005). Nicotine is an appetite suppressant, and practicing Sikhs may abstain from tobacco use and possibly increase their risk of increased BMI (Flegal et al. 1995). However, cigarette smoking was low in this population overall. Religious Muslims observe daily prayers, which some regard as daily exercise since it involves change in body position (Reza et al. 2002; Tirodkar et al. 2011; Greenhalgh and Helman 1998 Mar); prayers have not been shown to correlate with physical activity measures or weight changes. Cultural/religious and gender norms have also been shown to be a barrier to physical activity among South Asian women (Dave et al. 2012). In general, South Asians have reportedly low rates of physical activity, and in our sample, one-third of participants were relatively sedentary (<500 METS/min/week) (Joshi et al. 2007; US Department of Health and Human Services 2008).

Our study has several limitations. Given the cross-sectional design, we are unable to draw causal inferences about religious affiliation and BMI. Measures of religiosity, such as adherence to religious tenets or practices, were not measured and may provide further explanation for the positive association; future questionnaires will include questions on religious participation. Our sample was well educated, which may limit capturing associations between socioeconomic status, religion, and obesity. However, the sample reflects the South Asian community in the USA and their distribution by religious affiliation (Kanaya et al. 2013). There may have been inadequate power to detect associations between religious affiliation and BMI status among Jains, Christians, other, and multiple religion groups due to small sample sizes. Some researchers may contest using Asian-specific BMI cut-offs given no mortality differences among Asians at these lower cut-points (Zheng et al. 2011). We conducted a sensitivity analysis using different BMI classifications (i.e., BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 vs. BMI < 25 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 27.5 or 30 kg/m2 vs. BMI < 27.5 or 30 kg/m2 or BMI as continuous variable), and our results remained robust. Exclusion of underweight individuals or respondents >70 years old did not change our results. While those affiliated with Sikhism had a higher waist circumference compared with those with no religious affiliation (β = 3.6 in both models; p < 0.05), there was no significant relationship between abdominal obesity and religious affiliation (Alberti et al. 2006).

The links between religion, cultural beliefs, and weight in South Asian immigrants appear to be unique among other immigrant groups and deserve further exploration. The religious and cultural community may be synonymous for some South Asian groups, and South Asians may derive social support from these communities, which may be responsible for encouraging behaviors that increase overweight/obesity risk (Pollard et al. 2003). Obesity, often considered a lifestyle disease, may be influenced by religion and religious practices. For South Asians, who are at greater risk of obesity-related diseases, such as coronary heart disease and diabetes mellitus, religiously and culturally tailored interventions to promote healthy lifestyle behaviors may be especially critical.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- MASALA:

-

Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America

- USA:

-

United States of America

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- MESA:

-

Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- SHARE:

-

Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent of task

References

Ainsworth B. E., Haskell W. L., Herrmann S. D., Meckes N., Bassett D. R., Jr., Tudor-Locke C. et al.(2011) Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 43(8):1575–1581. PubMed PMID: 21681120. Epub 2011/06/18. eng.

Akresh, I. R. (2007). Dietary assimilation and health among hispanic immigrants to the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(4), 404–417.

Alberti, K. G. M. M., Zimmet, P., & Shaw, J. (2006). Metabolic syndrome—a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the international diabetes federation. Diabetic Medicine, 23(5), 469–480.

Barnes P, Adams P, Powell-Griner E. Health characteristics of the Asian adult population: United States, 2004–2006. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 394. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2008.

Basch, L., Schiller, N. G., & Blanc, C. S. (1994). Nations unbound: Transnational projects. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach.

Batis, C., Hernandez-Barrera, L., Barquera, S., Rivera, J. A., & Popkin, B. M. (2011). Food acculturation drives dietary differences among Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and non-Hispanic whites. The Journal of Nutrition, 141(10), 1898–1906.

Bharmal N, R MK, Shapiro MF, Kagawa-Singer M, Wong MD, Mangione CM, et al. (2013) The association of religiosity with overweight/obese body mass index among Asian Indian immigrants in California. Preventive Medicine, 57(4), 315–321. PubMed PMID: 23769898. Epub 2013/06/19. eng.

Bild D. E., Bluemke D. A., Burke G. L., Detrano R., Diez Roux A. V., Folsom A. R. et al. (2002) Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: Objectives and design. American Journal of Epidemiology, 156(9), 871–881. PubMed PMID: 12397006. Epub 2002/10/25. eng.

Chen L., Juon H.S., Lee S. (2012) Acculturation and BMI among Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese adults. Journal of Community Health, 37(3):539–546. PubMed PMID: 21922164. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3804273. Epub 2011/09/17. eng.

Cline K. M. C., Ferraro K. F. (2006) Does religion increase the prevalence and incidence of obesity in adulthood? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(2), 269-281. PubMed PMID: ISI:000238044000009.

Daniel, M., & Wilbur, J. (2011). Physical activity among South Asian Indian immigrants: An integrative review. Public Health Nursing, 28(5), 389–401.

Dave S. S., Craft L. L., Mehta P., Naval S., Kumar S., Kandula N. R. (20124) Life stage influences on U.S. South Asian women’s physical activity. American journal of health promotion: AJHP. PubMed PMID: 24717067. Epub 2014/04/11. Eng.

Deedwania P., Singh V. (2005) Coronary artery disease in South Asians: Evolving strategies for treatment and prevention. Indian Heart Journal, 57(6):617–631. PubMed PMID: 16521627. Epub 2006/03/09. eng.

Eliasi J. R., Dwyer J. T. Kosher and Halal (2002) Religious observances affecting dietary intakes. Journal of American Dietetics Association 102(7):911–913. PubMed PMID: ISI:000176711200005.

Feinstein M., Liu K., Ning H., Fitchett G., Lloyd-Jones D. M. (2010) Burden of cardiovascular risk factors, subclinical atherosclerosis, and incident cardiovascular events across dimensions of religiosity: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation, 121(5), 659–666. PubMed PMID: 20100975. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2871276. Epub 2010/01/27. eng.

Feinstein, M., Liu, K., Ning, H., Fitchett, G., & Lloyd-Jones, D. M. (2012). Incident obesity and cardiovascular risk factors between young adulthood and middle age by religious involvement: The coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Preventive Medicine, 54(2), 117–121.

Fekete, E. M., & Williams, S. L. (2012). Chronic Disease. In S. Loue & M. Sajatovic (Eds.), Encyclopedia of immigrant health. New York: Springer Publishing.

Fernandez, R., Miranda, C., & Everett, B. (2011). Prevalence of obesity among migrant Asian Indians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Evidence Based Healthcare, 9(4), 420–428.

Ferraro, K. F. (1998). Firm believers? religion, body weight, and well-being. Review of Religious Research, 39(3), 224–244.

Flegal K. M., Troiano R. P., Pamuk E. R., Kuczmarski R. J., Campbell S. M. (1995) The influence of smoking cessation on the prevalence of overweight in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 333(18), 1165–1170. PubMed PMID: 7565970. Epub 1995/11/02. eng.

Gadgil, M. D., Anderson, C. A. M., Kandula, N. R., & Kanaya, A. M. (2014). Dietary patterns and associations with metabolic risk factors in South Asians. Diabetes, 63((Supplement 1), A343–A425.

Garduno-Diaz S. D., Khokhar S. (2013) South Asian dietary patterns and their association with risk factors for the metabolic syndrome. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics, The official journal of the British Dietetic Association, 26(2):145–155. PubMed PMID: 22943473. Epub 2012/09/05. eng.

Ghai NR, Jacobsen SJ, Van Den Eeden SK, Ahmed AT, Haque R, Rhoads GG, et al. (2012). A comparison of lifestyle and behavioral cardiovascular disease risk factors between Asian Indian and White non-Hispanic men. Ethnicity and Disease, 22(2):168–174. PubMed PMID: 22764638. Epub 2012/07/07. eng.

Gillum R. F. (2006) Frequency of attendance at religious services, overweight, and obesity in American women and men: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Annals of Epidemiology, 16(9), 655–660. PubMed PMID: 16431132. Epub 2006/01/25. eng.

Greenhalgh, T., & Helman, C. (1998). Chowdhury AMm. Health beliefs and folk models of diabetes in British Bangladeshis: A qualitative study. BMJ, 316(7136), 978–983.

Guendelman, M. D., Cheryan, S., & Monin, B. (2011). Fitting in but getting fat: Identity threat and dietary choices among U.S. immigrant groups. Psychological Science, 22(7), 959–967.

Holland, A. T., Wong, E. C., Lauderdale, D. S., & Palaniappan, L. P. (2011). Spectrum of cardiovascular diseases in Asian-American racial/ethnic subgroups. Annals of Epidemiology, 21(8), 608–614.

Jih J., Mukherjea A., Vittinghoff E., Nguyen T. T., Tsoh J. Y., Fukuoka Y. et al. (2014) Using appropriate body mass index cut points for overweight and obesity among Asian Americans. Preventive Medicine, 65C, 1–6. PubMed PMID: 24736092. Epub 2014/04/17. Eng.

Jonnalagadda S. S., Diwan S. (2002) Regional variations in dietary intake and body mass index of first-generation Asian-Indian immigrants in the United States. Journal of American Dietetics Association, 102(9):1286–1289. PubMed PMID: 12792628. Epub 2003/06/07. eng.

Joshi P, Islam S, Pais P, Reddy S, Dorairaj P, Kazmi K, et al. (2007). Risk factors for early myocardial infarction in South Asians compared with individuals in other countries. JAMA, 297(3), 286–294. PubMed PMID: 17227980. Epub 2007/01/18. eng.

Kanaya, A. M., Kandula, N., Herrington, D., Budoff, M. J., Hulley, S., Vittinghoff, E., et al. (2013). Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians living in America (MASALA) study: Objectives, methods, and cohort description. Clinical Cardiology, 36(12), 713–720.

Karim, N., Bloch, D. S., Falciglia, G., & Murthy, L. (1986). Modifications in food consumption patterns reported by people from India, living in Cincinnati, Ohio. Ecology Of Food And Nutrition, 19(1), 11–18.

Karlson, K. B., & Holm, A. (2011). Decomposing primary and secondary effects: A new decomposition method. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 29(2), 221–237.

Karter AJ, Schillinger D, Adams AS, Moffet HH, Liu J, Adler NE, et al. (2013). Elevated rates of diabetes in Pacific Islanders and Asian subgroups: The diabetes study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Diabetes Care, 36(3), 574–579. PubMed PMID: 23069837. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3579366. Epub 2012/10/17. eng.

Kelemen, L. E., Anand, S. S., Vuksan, V., Yi, Q., Teo, K. K., Devanesen, S., et al. (2003). Development and evaluation of cultural food frequency questionnaires for South Asians, Chinese, and Europeans in North America. Journal of American Dietetics Association, 103(9), 1178–1184.

Kim, I. (1987). The Koreans: Small business in an urban frontier. In N. Foner (Ed.), New immigrants in New York. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kim, M. J., Lee, S. J., Ahn, Y. H., Bowen, P., & Lee, H. (2007). Dietary acculturation and diet quality of hypertensive Korean Americans. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58(5), 436–445.

Kim K.H., Sobal J., Wethington E. (2003) Religion and body weight. International Journal Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 27(4):469–477. PubMed PMID: 12664080. Epub 2003/03/29. eng.

Lapane, K. L., Lasater, T. M., Allan, C., & Carleton, R. A. (1997). Religion and cardiovascular disease risk. Journal of Religion and Health, 36(2), 155–164.

Lauderdale D. S., Rathouz P.J. (2000) Body mass index in a US national sample of Asian Americans: Effects of nativity, years since immigration and socioeconomic status. International Journal Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 24(9), 1188–1194. PubMed PMID: 11033989. Epub 2000/10/18. eng.

Lesser I.A., Gasevic D., Lear S. A. (2014) The association between acculturation and dietary patterns of South Asian immigrants. PloS one, 9(2), e88495. PubMed PMID: 24558396. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3928252. Epub 2014/02/22. eng.

Lv N., Cason K. L. (2004) Dietary pattern change and acculturation of Chinese Americans in Pennsylvania. Journal of American Dietetic Association, 104(5), 771–778. PubMed PMID: 15127063. Epub 2004/05/06. eng.

McGee, D. L., Liao, Y., Cao, G., & Cooper, R. S. (1999). Self-reported health status and mortality in a multiethnic US cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology, 149(1), 41–46.

Misra A, Khurana L. (2011). Obesity-related non-communicable diseases: South Asians vs white Caucasians. International journal of obesity (2005), 35(2):167–187. PubMed PMID: 20644557. Epub 2010/07/21. eng.

Moran AE, Forouzanfar MH, Roth GA, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJ, et al. (2014). Temporal trends in ischemic heart disease mortality in 21 world regions, 1980–2010: The global burden of disease 2010 study. Circulation, 129(14), 1483–1492. PubMed PMID: 24573352. Epub 2014/02/28. eng.

Mukherjea A., Underwood K. C., Stewart A. L., Ivey S. L., Kanaya A. M. (2013) Asian Indian views on diet and health in the United States: importance of understanding cultural and social factors to address disparities. Family and community health, 36(4):311–323. PubMed PMID: 23986072. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3987985. Epub 2013/08/30. eng.

Nguyen H. H., Smith C., Reynolds G.L., Freshman B. (2014) The effect of acculturation on obesity among foreign-born Asians residing in the United States. Journal of Immigrant and Minor Health. PubMed PMID: 24781781. Epub 2014/05/02. Eng.

Pollard TM, Carlin LE, Bhopal R, Unwin N, White M, Fischbacher C. (2003). Social networks and coronary heart disease risk factors in South Asians and Europeans in the UK. Ethnicity and Health, 8(3):263–275. PubMed PMID: 14577999. Epub 2003/10/28. eng.

Raj S., Ganganna P., Bowering J. (1999) Dietary habits of Asian Indians in relation to length of residence in the United States. Journal of American Dietetic Association, 99(9):1106-1108. PubMed PMID: 10491683. Epub 1999/09/24. eng.

Raymond, C., & Sukhwant, B. A. L. (1990). The drinking habits of Sikh, Hindu, Muslim and white men in the West Midlands: A community survey. Addiction, 85(6), 759–769.

Reza, M. F., Urakami, Y., & Mano, Y. (2002). Evaluation of a new physical exercise taken from Salat (Prayer) as a short-duration and frequent physical activity in the rehabilitation of geriatric and disabled patients. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 22(3/4), 177–180.

Tirodkar M. A., Baker D. W., Makoul G. T., Khurana N., Paracha M. W., Kandula N. R. (2011) Explanatory models of health and disease among South Asian immigrants in Chicago. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13(2), 385–394. PubMed PMID: 20131000. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2905487. Eng.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2012) The Asian population: 2010 http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2008) Physical activity guidelines for Americans http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/chapter1.aspx.

Wang E. T., de Koning L., Kanaya A. M. (2010) Higher protein intake is associated with diabetes risk in south asian indians: The metabolic syndrome and Atherosclerosis in South Asians living in America (MASALA) study. Journal of the American College Nutrition 29(2):130–135. PubMed PMID: 20679148. Epub 2010/08/04. eng.

World Health Organization expert consultation. (2004) Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet., 363(9403), 157–163. PubMed PMID: ISI:000187939200021.

Ye, J., Rust, G., Baltrus, P., & Daniels, E. (2009). Cardiovascular risk factors among Asian Americans: Results from a national health survey. Annals of Epidemiology, 19(10), 718–723.

Zheng, W., McLerran, D. F., Rolland, B., Zhang, X., Inoue, M., Matsuo, K., et al. (2011). Association between body-mass index and risk of death in more than 1 million Asians. New England Journal of Medicine, 364(8), 719–729.

Zhou, M. (1992). Chinatown: The socioeconomic potential of an urban enclave. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Acknowledgments

The MASALA study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01HL093009 and R01HL120725. N. Bharmal received support from the University of California, Los Angeles, Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME NIH/NIA Grant Number P30-AG021684) and the Los Angeles Stroke Prevention and Intervention Research Program in Health Disparities (NIH/NINDS 1U54NS081764). W. McCarthy received support from National Institutes of Health Grant 1P50HL105188#6094.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bharmal, N.H., McCarthy, W.J., Gadgil, M.D. et al. The Association of Religious Affiliation with Overweight/Obesity Among South Asians: The Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) Study. J Relig Health 57, 33–46 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0290-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0290-z