Abstract

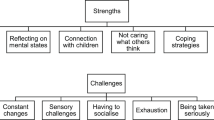

Ample quantitative studies have shown that parents raising children with neurodevelopmental disabilities are prone to experience more stress and challenges in their parenthood. Notwithstanding the strength of this line of research, qualitative studies are crucial to grasp the complex reality of these parenting experiences. This qualitative study adopted the Self-Determination Theory to analyze parents’ described experiences, appraising both challenges and opportunities in parents’ psychological need for autonomy, relatedness, and competence. A multi-group comparative design is adopted to examine similarities and differences in the perspectives of 160 parents raising an adolescent with autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, or without a disability (M age child = 13.09 years, 67.5% boys). Parents’ perspectives were examined through speech samples probing parents to talk spontaneously about their child, their relationship with the child, and their parental experiences. Forty samples in each group were randomly chosen from a larger dataset and were analyzed using deductive thematic analysis. Parents of children with a disability described more need-frustrating but also more autonomy-satisfying experiences compared to parents of children without a disability. Parents of children with autism spectrum disorder reported the most challenges concerning their relatedness with their child and their own parental competence. Parents raising a child with cerebral palsy expressed the most worries about their child’s future and continuity of care. Parents of a child with Down syndrome described the most need-satisfying experiences in their family life. This study offers a more balanced view on the realm of parenting a child with a neurodevelopmental disability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Parenting is an emotionally powerful and complex undertaking, which strongly affects parents’ well-being (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020). When a child is growing up with a social, physical, or intellectual disability, due to a neurodevelopmental disability (NDD) such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), cerebral palsy (CP), or Down syndrome (DS), parents face additional challenges in providing their child with the needed care. These parents are required to make adjustments to their daily life, but they also need to adjust their expectations towards their own parental role, aspirations, and future life (Reichman et al., 2008; Resch et al., 2010). Over the past decades, research into the experiences of parents raising a child with a disability in general, and children with a NDD more specifically, has predominantly focused on the rather negative impact of a child’s disability on parents’ well-being and functioning. More specifically, of the various focal points in family research that aim to capture these parental experiences, the most widely investigated topic is that of parental stress (e.g., Valicenti-McDermott et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2011). Within this line of research, ample quantitative studies have demonstrated that parents of children with a NDD share an increased vulnerability to experience higher levels of parenting stress and lower levels of well-being compared to parents of children with no disability (Gupta, 2007; Hayes & Watson, 2013; Singer & Floyd, 2006). However, these studies focusing on the construct of parental stress provide a rather one-sided view on the daily reality of raising a child with a NDD, often overshadowing parents’ positive or satisfying experiences.

Self-Determination Theory: Towards a More Balanced View on Parenting a Child with a Neurodevelopmental Disability

To offer a more profound and balanced insight into both challenging and satisfying experiences when parenting a child with a NDD, the widely-validated theoretic framework of Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 2000; Soenens et al., 2017) is suggested to be particularly valuable (Dieleman et al., 2018; Dieleman et al., 2019). According to this theory, the development and growth of an individual largely depends on the extent to which a social environment supports or frustrates three innate basic psychological needs: the need for autonomy (i.e., to feel psychological freedom and authentic), relatedness (i.e., to feel connected with and loved by others), and competence (i.e., to feel able and effective to reach personal goals) (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Especially among neurotypical populations, the SDT-framework is a prominent theory to unravel how parents’ need-frustrating (e.g., feelings of pressure, social alienation, and personal failure) and need-satisfying experiences (e.g., experiences of authenticity, reciprocal care, and personal effectiveness) impact parents' well-being, vitality, and self-development (e.g., Soenens et al., 2017, 2019; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013).

Inspired by the assumption that SDT has universally applicable tenets (Deci & Ryan, 2000), there is now growing interest to use this theory to better understand the complex realm of parents raising a child with a disability, both using quantitative (e.g., Dieleman et al., 2020; Gilmore & Cuskelly, 2012) and qualitative methodologies (Dieleman et al., 2018; Dieleman et al., 2019; Gilmore et al., 2016). Interestingly, the SDT distinction between two pathways of need satisfaction versus need frustration, may help to capture the phenomenon of silver linings (Bultas & Pohlman, 2014). A few qualitative studies of parents raising a child with a disability now indicate that, despite frequent adversities, parenting is not always doom and gloom but also entails enriching need-satisfying experiences (e.g., Dieleman et al., 2018; Gilmore et al., 2016). To date, research evaluating SDT in disabilities has mostly focused on one single NDD, with little input from similar research on another NDD. Therefore, this study examines the need-related experiences of parents raising a child in and across three diverse NDDs, namely ASD, CP, and DS. We selected these NDDs because of their high prevalence (Elsabbagh et al., 2012; Irving et al., 2008; Oskoui et al., 2013) but also based on the diversity of the developmental domain in which limitations occur (i.e., social-communicative in ASD, physical in CP, and cognitive in DS).

Self-Determination Theory as a Lens to Synthesize the Experiences of Parents Raising a Child with a Neurodevelopmental Disability

The current, blossoming literature to validate SDT-premises in studies on parenting a child with a disability primarily builds upon two classic research methodologies: i.e. questionnaires and interviews. The current study introduces a third, innovative design and evaluates the potential of SDT to synthesize naturalistic, spontaneous speech samples of parents.

Questionnaire Data: Evaluating Parental Stress as Psychological Need Frustration

To date, parent-report questionnaires are the first and preferred method to quantitatively evaluate parental experiences. A handful of studies now explicitly used SDT to better understand the a-theoretical construct of parental stress in terms of frustration of parental needs for autonomy, relatedness, or competence (e.g., de Haan et al., 2013). Within NDD-populations, these studies demonstrated that parents of children with ASD (Dieleman et al., 2018; Dieleman et al., 2019), CP (Dieleman et al., 2020), and DS (Gilmore & Cuskelly, 2012) are more vulnerable to experience elevated levels of parental need frustration (De Clercq et al., 2021). Moreover, these elevated levels of need frustration have been empirically linked with dysfunctional parenting behaviors in both long-term (Dieleman et al., 2017) and diary studies (Dieleman et al., 2020; Dieleman et al., 2019) among families raising a child with ASD or CP. In turn, these dysfunctional parenting behaviors have been associated with more externalizing problems and fewer psychosocial strengths across children with and without ASD, CP, and DS (De Clercq et al., 2019).

In-depth Interviews: Unraveling Complexity

The past decade has witnessed a growing body of qualitative work on experiences of parents raising a child with ASD, CP, and DS (e.g., Alaee et al., 2015; Farkas et al., 2018; Meirsschaut et al., 2010), including two recent, SDT-based studies in ASD (Dieleman et al., 2018) and CP (Dieleman et al., 2019). These studies are mainly based on in-depth or (semi)structured interviews and demonstrated that the SDT-lens is a valuable tool to integrate qualitative findings of parents’ experiences in terms of need satisfaction and need frustration.

For instance, in ASD-research, parents describe need frustration when they experience a lack of time or possibilities to develop their own interests (i.e., autonomy frustration) or strain in their relationship with their partner and friends (i.e., relatedness frustration) (Dieleman et al., 2018). Parents of children with ASD also report frustration in their need for parental competence when they struggle to find the right approach to manage challenging child behaviors (Dieleman et al., 2018; Meirsschaut et al., 2010; Myers et al., 2009; Woodgate et al., 2008). In CP-research, parents also report autonomy frustration when they experience restrictions to develop their own interests or whey they must give up their professional aspirations. When these parents experience limited time to spend as a couple or lack time and energy to maintain social contacts, this can be interpreted as frustrations in their need for relatedness (Alaee et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2010; Dieleman et al., 2019). Parents of children with CP also report competence frustration regarding the difficulties they face to provide and organize specialized care, or to interpret their child’s needs (Dieleman et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2010). Similarly, research among parents of children with DS also identifies multiple examples of autonomy frustration, such as the feeling that they need to invest too much of their free time to organize medical and therapeutic support (Povee et al., 2012). Parents of children with DS also mention relatedness frustration, such as a lack of social acceptance or support from their family or friends, or competence frustration, such as struggling to get access to services or feeling uncertain to make decisions regarding their child’s education (Farkas et al., 2018; Povee et al., 2012).

Evaluating existent qualitative studies through an SDT-lens also illuminates positive need-satisfying experiences. For instance, parents of children with ASD report opportunities for need satisfaction, such as finding a new direction in life (i.e., autonomy satisfaction), growing closer together as a family (i.e., relatedness satisfaction), or feeling proud when their child achieves certain goals (i.e., competence satisfaction) (DePape & Lindsay, 2014; Dieleman et al., 2018). Studies among parents raising a child with CP highlight relatedness satisfaction when they mention intense parent–child relationships, new social networks or strong family cohesion (Björquist et al., 2016; LaForme Fiss et al., 2014). Parents of children with CP report that they especially feel competent when their child reaches an unexpected goal or when specialized healthcare professionals recognize the positive evolutions of their child (Davis et al., 2010; Dieleman et al., 2019). Additionally, parents raising a child with DS report experiences of autonomy satisfaction when their child enhances their self-development or shapes their philosophy of life (e.g., by appreciating diversity, learning to be more patient and flexible) (Povee et al., 2012). These parents also report relatedness satisfaction describing how their child facilitates new friendships (Farkas et al., 2018) and competence satisfaction when their child acquires new skills that maximize the child’s independence (Gilmore et al., 2016).

Spontaneous Free Speech Samples: Exploring Naturalistic Experiences

In addition to the more traditional methodologies of questionnaires and in-depth interviews, this study adopts SDT as a lens to synthesize spontaneous free speech samples of parents describing their child, the relationship with their child, and their parental experiences. In recent years, the interest in the free speech sample method has gradually grown to capture more naturalistic family life experiences, both quantitively and qualitatively. In parenting and broader developmental research, the Five Minute Speech Sample (FMSS) (Magaña-Amato et al., 1986) became a widely-validated operationalization of this method (Sher-Censor, 2015; Thompson et al., 2018). Within this method, parents are asked to speak spontaneously for five minutes about what kind of person their child is and how they experience the relationship with their child, without being interrupted by interview questions (Magaña-Amato, 1993).

The FMSS-method is traditionally used in quantitative studies to measure parents’ levels of Expressed Emotion (i.e., low or high intensity and regulation of emotion in parents’ expressions) through a structured coding scheme (Magaña-Amato, 1993). In both neurotypical (Sher-Censor, 2015) and NDD-populations (e.g., Hastings et al., 2006; Hickey et al., 2020; Yığman et al., 2020), scholars now argue that high levels of parental Expressed Emotion can be interpreted as an indicator of a stressed-out family climate, where parents’ experiences of stress are elevated. Notably, a few studies explored the rich, naturalistic information embedded in these parents’ spontaneous free speech samples. These studies qualitatively examined speech samples among caregivers of children with a disability (Kovac, 2018; Perez et al., 2014), behavioral difficulties (Caspi et al., 2004), or children growing up in precarious living situations and poverty (de Wit, 2018) using diverse qualitative techniques, such as computer-based linguistic analysis, thematic, or content analysis. Two studies applied a qualitative analysis of FMSSs to evaluate whether caregivers’ perceptions and attitudes towards the child and their relationship with the child positively evolved after an intervention or parenting program (de Wit, 2018; Kovac, 2018). Similarly et al. (2004) and Perez et al. (2014) suggested that the FMSS-method is a useful tool to examine parents’ perceptions and attitudes towards their child’s behavior in general, and diagnosis in particular (e.g., ADHD or antisocial behavior). Moreover, a better understanding of these perceptions and attitudes provided guidelines to increase the quality of parent–child relationships and to maximize the relevancy and effectiveness of parenting interventions (Caspi et al., 2004; Perez et al., 2014). For instance, the qualitative examination of parents' narratives showed that parenting interventions should not only include techniques to improve effective behavior management and communication skills but should also include strategies that focus on promoting affectionate parent–child relationships, positive perceptions, and activities that facilitate enjoyment and positive mood within the family context (Perez et al., 2014).

The Present Study

This qualitative study aims to provide a deeper understanding of the perspectives of parents raising an adolescent with ASD, CP, DS, and a reference group of parents raising a child without any known disability (i.e., reference group). The inclusion of these four groups allows a multi-group qualitative comparative design, providing the opportunity to examine parents’ experiences as a whole, while also shedding light on group-specificities (Lindsay, 2018; Morse, 2004; Ritchie et al., 2003). In other words, this design permits to examine general overarching parental experiences, generalizing across groups, while also exploring differences across groups. These group differences might provide valuable insight into the factors that make raising a child with a certain NDD potentially stressful, but also into those factors that create possibilities for positive need-satisfying experiences. This study examined parents’ perspectives through spontaneous descriptions, where parents were asked to talk about what kind of person their child is, how they get along with their child (cf., FMSS-method instruction), and their parenting experiences. Whereas interviews tend to follow a certain interview guideline that might bias or steer participants into a certain direction or might elicit social desirability (Ritchie et al., 2003), spontaneous speech samples ought to provide a more ecological look into people’s experiences. The SDT-framework was applied to structure these spontaneous speech samples in order to provide a more balanced view on parents’ perspectives regarding their need for autonomy, relatedness, and competence.

Method

Participants

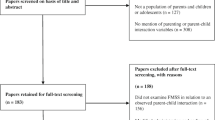

As part of an ongoing longitudinal project, 489 speech samples of parents raising a child with ASD (n = 159), CP (n = 88), DS (n = 69), and without any known disability (n = 174) were collected (De Clercq et al., 2021). 40 Interviews from each group (total n = 160) were randomly selected to reflect similar socio-demographic characteristics across groups, while also ensuring sufficient sample sizes to reflect diversity and to retain in-depth coverage and thematic saturation (Lindsay, 2018; Ritchie et al., 2003). More specifically, the four parent groups were closely distributed based on: the child’s gender (2:3, boys:girls), age (ranging from 10 to 15 years old), and living situation (overall, 85.0% of the children lived at home during the week and weekends), and the informants’ relation towards the child (35:5, mothers:fathers), age (overall Mage mother = 44.36 years, overall Mage father = 46.44 years), educational level (overall 68.8% higher education), and marital status (overall 77.5% living together/married). Additional sample characteristics by group are presented in Table 1.

Procedure

Parents were eligible to participate in the longitudinal project if their child (1) had an official ASD, CP, or DS diagnosis, or received no clinical diagnosis and (2) was between 6 and 17 years old. Parents of children with a NDD provided information on their child’s diagnostic process and were asked to verify their child’s diagnosis through additional reports. These parents were recruited via specialized care facilities, schools, and online parent groups. Parents from the reference group raised a child between 6 and 17 years old, who did not receive a clinical diagnosis. These parents were included from the Flemish Study on Temperament and Personality across Childhood (De Pauw, 2010).

At the beginning of the interview, parents were asked to provide some general demographic information about their child and family (Table 1). Parents’ perspectives were administered through short interviews, either in the family home or through telephone. Both approaches showed to have good validity to assess free speech samples (Beck et al., 2004). The data collection consisted of two structured open-ended questions (i.e., Could you tell me about the kind of person your child is and how you get along? Could you tell me about your experiences as a parent of [name child]?) to explore the same issues across samples (Ritchie et al., 2003). The first question is the official instruction of the FMSS-method, where parents are asked to speak (at least) for five uninterrupted minutes about what kind of person their child is and how they get along together (Magaña-Amato et al., 1986). Concerning the second question, parents were encouraged to spontaneously speak about their experiences as a parent, for at least three minutes. The interviewer did not say anything while the respondent was speaking, which meant that the interviewer did not provide any comments, verbal affirmations, or leading prompts that could direct the conversation. When the parent stopped talking before the end of the proposed amount of minutes, the interviewer waited for 20–30 s, and if the parent did not continue talking, the interviewer repeated the interview instruction (cf., FMSS-method instruction; Magaña-Amato, 1993). Parents’ speech samples ranged from 8.33 to 19.05 min (M = 11.19). Written informed consent was obtained from all parents and the study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences at Ghent University, in accordance with internationally accepted criteria for research.

Data Analysis

All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using the qualitative software program Nvivo (QSR International, 2012). The data analysis followed the principles of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Because parents’ perspectives were analyzed using the SDT-framework (i.e., need for autonomy, relatedness, and competence), a deductive theory-driven thematic approach was used. The data-analytic process started with data familiarization and noting initial comments about meaningful information across groups to get a sense of the whole, before comparing similarities and differences across groups (Lindsay, 2018). Next, initial codes were generated through line-by-line coding and organized into potential (sub)themes. The coding process followed a specific sequence, where the coding of ten samples from a specific group was followed by the coding of ten samples from another group, and so on, until all data of 40 samples within each group were coded. This approach allowed to minimize possible group bias effect (Lindsay, 2018). Further, all (sub)themes were critically appraised on whether they formed a coherent pattern and accurately represented parents’ perspectives by discussing the content of the (sub)themes and how they related to each other within the research team. Next, (sub)themes were reconsidered and reflected upon by multiple researchers of the research team to increase credibility and to limit personal bias (Shenton, 2004). Finally, each theme was defined within the research team and associated quotes were discussed to identify a selection of descriptions reflecting the overarching topic. Irrespective of the steps described, the analytic process was not linear, but involved loops going back and forth between the different steps (Howitt, 2016). Parents’ perspectives were structured within the framework of SDT and categorized as need-frustrating or need-satisfying experiences in parents’ need for autonomy, relatedness, or competence. More specifically, we examined how parents’ experiences related to feelings of satisfaction or frustration concerning their psychological freedom and feelings of authenticity (i.e., autonomy), feelings of connectedness and feeling loved by others (i.e., relatedness), and feeling able and effective to reach personal goals (i.e., competence).

For exploratory purposes, we first examine whether the amount of parents’ need-related experiences relate to socio-demographic factors (see Table 1) using correlation analyses and MANOVAs in SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Next, we focus on the content of parents’ experiences and how these might differ across groups.

Results

Preliminary analyses indicated that the amount of parents’ need-related experiences related to certain socio-demographic information. More specifically, whereas parents of older children with DS mentioned more competence-satisfying experiences (r = 0.32, p = 0.04), parents of older children from the reference group mentioned less of these experiences (r = -0.42, p = 0.01). Furthermore, parents of children with DS raising a boy or a child who followed a specialized schooling trajectory mentioned more autonomy-frustrating experiences compared to parents of girls (F(1,38) = 9.77, p < 0.01) or parents of children in a regular school trajectory (F(1,38) = 4.40, p = 0.04). Also disability severity seemed to influence parents’ need-related experiences since parents of children with DS reported more autonomy- (F(2,37) = 3.42, p = 0.04), relatedness- (F(2,37) = 6.66, p = 0.01), and competence-frustrating experiences (F(2,37) = 6.17, p = 0.01) compared to parents of children with a mild or moderate disability severity. The significant effect concerning autonomy-frustrating experiences was also significant in the CP-group (F(2,37) = 3.30, p < 0.05). Finally, we found that single parents of children with CP (F (2,37) = 4.58, p = 0.02), DS (F (2,37) = 6.06, p = 0.01), and without any known disability (F (2,37) = 7.74, p = 0.01) reported more relatedness-frustrating experiences compared to parents who lived together with a partner or in a new assembled family. Taken together, these quantitative analyses indicate that parents’ subjective experiences might be influenced by socio-demographic variables, such as child age, child gender, the child’s schooling trajectory, disability severity, and the parents’ marital status.

The results of the main analyses indicate that, overall, parents of children with ASD, CP, and DS described more need-frustrating experiences in all three psychological needs compared to parents of children without any known disability. Interestingly, parents raising a child with DS described a similar – and regarding autonomy and relatedness even a higher – amount of need-satisfying experiences compared to parents of the reference group. An overview of these themes and their frequency in each group, is presented in Table 2. Figure 1 visually represents the count of opportunities and challenges that parents described in their needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence.

Frustration and Satisfaction in the Need for Autonomy

Within descriptions of parents’ need for autonomy, two salient themes emerged: self-development and family life. Notably, only parents of children with a NDD spontaneously described autonomy-frustrating experiences related to their self-development and family life, whereas all parents mentioned autonomy-satisfying feelings of enrichment or family cohesion.

Self-Development: Role Restriction Versus Enrichment

Role restriction

Challenges for self-development only emerged in the free speech samples of parents of children with a NDD. Several parents of children with ASD felt forced to be near their child all the time or to “stick with old patterns or activities”. According to these parents, these experiences related to their child’s anxiety to rely on others or to do things alone, their child’s need for predictability, or adversity towards new stimuli. Many parents of children with CP also mentioned role restriction because their child needed a lot of practical support (e.g., eating, washing, clothing), emphasizing that the management of specialized care was time-consuming.

You sacrifice a part of your own life, a part of your own life is lost. You have less freedom. You have less free time to do the things you used to do, but you learn to live with it. (Mother of J., boy with CP)

One-third of the parents raising a child with DS described that their personal time was limited because their child needed a lot of proximity and supervision during activities, or needed a lot of stimulation to do things alone. This, however, required a lot of explanation, probing, control, and repetition. Therefore, some of these parents found it difficult to leave their child alone at home, which further hindered their possibilities to go out. Some parents of children with a NDD also mentioned restrictions in their chances to pursue a professional career. Eight of these parents spontaneously mentioned they decided to work less and three parents gave up their professional ambitions. Whereas half of these parents experienced feelings of regret to do so, others mentioned that this decision allowed them to provide the needed care for their child and to arrange the household. Especially parents of children with CP cut back quite early a few steps in their professional career to keep up with the appointments with doctors and therapists.

It is not always easy to keep a job while raising a child with a disability… you have to go to hospitals a lot, see doctors, all that. Colleagues do not really understand that. (Mother of B., girl with CP)

Enrichment

In all groups, there were many expressions of parents indicating that raising their child is a positive and rewarding experience, enhancing their self-development and changing their perspective on life. Especially parents of children with DS mentioned that they became more reflective, creative or resilient when handling challenges, or developed a more down-to-earth view on life (i.e., putting things in perspective, living in the moment, enjoying “the little things”).

I learned a lot from [name child]. She can be so satisfied and happy with small things. I really try to think about that regularly. Given our society's emphasis on accomplishments, that’s not always evident. I think we always want more, and bigger and better, but for A., good is good enough. (Mother of A., girl with DS)

Around one sixth of the parents raising a child with a NDD described feelings of empowerment when they responded with resilience towards barriers and confrontations, such as legal care provisions or stigmatization. Some of these parents saw it as their duty to take an active role in "fighting for their child’s participation and inclusion”, or to be an advocate for their child, for example, by organizing inclusive schooling or leisure activities, or by coaching care providers.

Many care providers think in a restrictive way and assume she is not able to do things, and then I find that I must take action. I really learned to be assertive and to be more provocative, in a friendly and respectful manner of course. I try to coach care providers in how you can support her and stimulate her the most. (Mother of N., girl with DS)

Some parents of children with DS even felt they had to “claim a secure place in society” for their child. They questioned the current view on prenatal screening and took an active role in defending the right to live for people with DS. Parents hoped that in the future, medical staff would engage more often in an open and balanced dialogue about these screenings, which reflected the positive side of raising a child with DS. Also, five parents of children with a NDD mentioned that changes in child (e.g., increased independence) or contextual factors (e.g., different care providers located in the same care facility instead of scattered) increased their opportunities for self-development.

Family Life: Challenging Family Activities Versus Intensified Family Cohesion

Challenging family activities

Parents of children with a NDD mentioned multiple challenges to commit to or adjust family and holiday activities. Especially parents of children with ASD mentioned that they had to restructure or cancel family activities due to the child’s need for structure and predictability, or because social events caused over-stimulation (e.g., too crowded, noisy, other food). Particularly parents of children with ASD and CP mentioned limitations related to family holidays. Whereas some parents of children with ASD were not able to go on a family holiday because it was too stressful or exhausting to provide enough structure and predictability, parents of children with CP were confronted with the inaccessibility of locations or activities, which could also create tensions with siblings.

Going somewhere, does it work or not? We never know in advance. Looking ahead or planning doesn't exist for us. So, life is quite difficult. When we want to go somewhere, we are always stressed because we don’t know if it will work out. (…) A normal school day is already difficult, let alone a holiday where nothing is planned. (Mother of V., boy with ASD)

Of course, everything depends on him, we can't just go on vacation anywhere. We have to see whether it is accessible... and even then, it is always a bit of a compromise. (Mother of F., boy with CP)

Intensified family cohesion

Parents of children with DS and from the reference group also spontaneously mentioned many autonomy-satisfying experiences related to their family life. Whereas several of these parents described that they felt unrestricted and happy to bring their child to family activities or social events, other parents mentioned that their child enriched their family life because the child created or enhanced a positive atmosphere in the family unit.

Frustration and Satisfaction in the Need for Relatedness

Parents from each group spontaneously described many challenges and opportunities in their need for relatedness with their child and other siblings, and their social network (i.e., partner, family, friends, unacquainted people, care providers). Notably, only parents of children with a NDD mentioned relatedness frustration beyond the parent–child relationship into their relation with their social network and care providers.

Relatedness with the Child: Intensity Versus Indispensability

Intensity

All parents mentioned different challenges in relatedness with their child, yet their content differed substantially across groups. Parents from the reference group especially described difficulties in the context of puberty, noting that their child “pushed them away” to be more independent, showed more rebellious behavior (e.g., not adhere to rules and agreements, offer a rebuttal), was more talkative towards their friends instead of their parents, or liked to be in the spotlight all the time. Among parents of children with ASD, the parent–child relationship was often described as “challenging” characterized by conflicting signals. These parents struggled to reach reciprocity due to their child’s communication difficulties or preference to be alone. Several of these parents felt pressured or dissatisfied when their child too strongly relied on them to fill in their free time, to translate social interactions, to provide structure and predictability, or when they were confronted with physical aggression and tantrums. About three-quarters of the parents raising a child with CP described their parent–child relationship as “intense”, characterized by enduring care and demanding support needs (e.g., clothing, eating, washing, putting on aids, going to therapies and hospitals) and dependence, which sometimes felt strenuous and exhausting. Some of these parents even indicated that their relationship with their child felt more stressful during puberty, as the child wanted to dismiss itself from the parent but also unwillingly had to depend on the parent’s care for everyday things.

At the moment, my relationship with him is more difficult. I think he is in puberty, but not physically though. He can really push me away and say: “Leave me alone, I don't need you.” (Mother of S., boy with CP)

About one-third of the parents raising a child with DS mentioned that their parent–child relationship was often under strain since their child required a lot of affection, proximity, and/or supervision, which could feel very tiring for some parents.

Right now, he has been mom-oriented for months, and then it is always mom who has to do it. Nobody else can do anything. Mommy has to wash him, has to dress him, has to give him food, has to go to bed with him. It's all mommy mommy mommy and that requires a lot from a person. (Mother of I., boy with DS)

Indispensability

Across all groups, many parents spontaneously mentioned need-satisfying experiences in their parent–child relationship, characterized by a unique connection or understanding. About half of the parents from the reference group described their parent–child relationship as “open”, referring to a relationship where the child spontaneously shared his or her thoughts and feelings, and showed affection towards the parent. Parents of children with ASD mentioned that over time they better understood their child’s thought processes and support needs, and were able to recognize more subtle signs of relatedness. Some of these parents described themselves as “interpreters” or “soundboards” as they were often the ones translating their child’s thoughts and feelings to the outside world and the other way around. Other parents of children with ASD used the term “emotional resting places” to describe themselves as a place where the child felt comfortable and understood. Parents of children with CP especially mentioned that due to the large amount of time they spent together with their child and due to the intensive practical and emotional support, parents felt indispensable for their child, which created a unique and close parent–child relationship. The majority of the parents raising a child with DS described their parent–child relationship as “warm”, characterized by a lot of physical affection, open communication, and humor. According to these parents, this warm relationship was facilitated due to the fact that their child liked social moments, easily picked up other people’s feelings, expressed their love very expressively, or often showed gratitude.

Relatedness with Siblings: Distributing Attention Versus Nurturing Sibling Relationships

Distributing attention

In each group, several parents (with multiple children) struggled to provide equal attention to each of their children and to build qualitative relationships with each child. Whereas some parents from the reference group struggled to do so in the context of a newly assembled family, parents of children with a NDD felt uncertain about how far the adaption of rules and expectations towards their children could go in order to meet each child’s needs. Sometimes siblings reacted frustrated because they felt treated unequally (e.g., less parental attention, more chores in the household, more parental demands to be flexible) or the child with a NDD felt jealous towards the sibling because s/he was not able or allowed to participate in a similar activity (e.g., meeting alone with friends, going to a party).

His brother feels depressed that his oldest brother is autistic and requires so much attention. He feels neglected, less worthy. So it's a bit of a hassle to pay equal attention to the children. (Mother of X., boy with ASD)

Nurturing sibling relationships

Across groups, parents mentioned relatedness satisfaction when their children got along well. Twenty parents of children with CP or DS stated that having a child with a disability brought the family closer together or made the sibling more caring towards others. Especially when the developmental age of a child with DS matched that of a (younger) sibling, the sibling relationship seemed to be facilitated.

Relatedness with Social Network: Feeling Misunderstood Versus Feeling Supported

Feeling misunderstood

Parents mentioned relatedness frustration when they felt misunderstood by important others. Whereas parents from each group mentioned frustrating experiences in their partner relationship, only parents of children raising a child with a NDD mentioned these experiences concerning their relationship with their family, friends, unacquainted people, and care providers. Concerning the partner relationship, several parents felt frustrated when they had limited time to spend as a couple due to all the parenting tasks or when they disagreed on how to handle certain parenting situations. For parents of a child with a NDD, these disagreements often related to discussions about the practical organization of care tasks or setting similar expectations for the child with a NDD and the sibling(s). Furthermore, only parents of children with a NDD mentioned relatedness-frustrating experiences with family or friends, particularly when family and friends did not understand or minimized the impact of raising a child with a disability. Especially parents of children with ASD felt misunderstood when family or friends stated that certain difficulties (e.g., not wanting to do schoolwork, aggression) could be “fixed” by parenting differently (e.g., being stricter). Some parents of children with a NDD lost friends due to a lack of time or energy to participate in social activities or because joined activities with other families mismatched their child’s needs (e.g., too many stimuli, required walking skills).

A family with a child with a disability is a limited family. That is very clear. So this makes it really difficult. Especially towards social contacts, you become somewhat isolated. Your friends stay away a bit, you have less energy, and if you go somewhere, you don’t know if it will work out. (Father of F., boy with DS)

Furthermore, the physical (in)visibility of the child’s NDD played a salient factor in parents’ relatedness frustration with unacquainted people. For example, parents of children with ASD felt that unacquainted people were less understanding or reacted irately when their child behaved “inappropriately”, urging parents to constantly “justify” their child’s behavior. Also, according to parents of children with DS, the stereotypical idea about DS (i.e., being kind, loving, affectionate) did not always match their child’s needs or personality, and even felt as an underestimation of their struggles as a parent. About one in six parents of children with a NDD also mentioned painful experiences, such as being stared or laughed at, or when receiving pitying or indignant looks. Although their child was often not aware of these experiences, they had a strong impact on parents and made them feel sad, angry or “different”.

When I get into the (public) swimming pool with her, you always have people going out of the pool. Then I always feel like saying: “It's not contagious!”. But yes, that affects me. Why do they do that, or why do they look that way, why do they react like that? I think about that. (Mother of A., girl with DS)

Parents of children with a NDD also mentioned intense and long-lasting contacts with a broad group of care providers. They discussed elements of need frustration when care providers did not take their concerns seriously, only focused on their child impairments, underestimated their child’s abilities, or instead asked too much of the child (and themselves).

Those doctors keep saying what to do, but in the meantime, it’s very hard for us to do everything the right way. (…) My child has to do so much more than another child. It is very difficult because every specialist tells him what to do. And if you want to follow up all that, the poor child has no time for himself and neither do we. (Mother of M., boy with CP)

Feeling supported

Across each group, several parents mentioned relatedness satisfaction in the relationship with their partner when they worked together as a team to overcome challenges, pursued similar parenting goals, or supported each other in their parenting style. Eight parents of children with a NDD even mentioned that their partner relationship became more intense after their child with a disability was born. They pointed out that it was essential to respect each other's way of dealing with their child’s diagnosis, and to support and comfort each other during the acceptance process or when going through difficult moments. In each group, family and friends were salient sources of support for both practical (e.g., taking care of the child once and a while) and emotional reasons (e.g., exchanging parental experiences, listening to concerns). Parents of children with a NDD especially experienced renewed energy when family or friends attentively listened to uncertainties or frustrations, recognized their parental efforts, or noticed small acts of progress in their child’s development. Friendships that endured became extra meaningful and valuable, and new friendships with other parents of children with disabilities (for example through parenting groups) were treasured as these parents understood their situation and provided useful tips to handle challenges. In their interaction with unacquainted people, some parents of children with ASD also valued the invisibility of their child’s disability because it caused less stigmatization. By contrast, some parents of children with CP and DS valued the visibility of their child’s disability because the environment could immediately adjust to their child’s abilities. In relation to care providers, parents felt connected when care providers noticed and valued the strengths of their child, collectively searched for solutions, acknowledged parents’ hard work, or motivated parents to continue.

Frustration and Satisfaction in the Need for Competence

In each group, many parental remarks were allocated as competence-related experiences, which were mainly related to feeling (less) competent in parental practices and skills. Parents of children with a NDD described more competence-frustrating experiences concerning their parental identity, the provision of external support, and their child’s future. Whereas competence-satisfying experiences encompassed an affective component of pride and relief, competence-frustrating experiences included feelings of exhaustion, powerlessness, or misunderstanding.

Parenting: Struggling to Provide Versus Relying on Need-Supportive Parenting Behavior

Across groups, parents’ competence-related experiences were primarily and bi-directionally related to their own parenting behaviors and more specifically, the extent to which they felt they struggled or, conversely, adequately responded towards their child’s need for autonomy, relatedness, and competence (i.e., need-supportive parenting).

Struggling to provide need-supportive parenting

In all groups, parents described feelings of uncertainty while struggling to support their child’s need for autonomy. Especially parents from the reference group described struggles to find a balance between allowing more freedom (e.g., going to a party, staying home alone) and providing enough boundaries. A minority of parents of children with ASD spontaneously mentioned to use autonomy-thwarting parenting behaviors, such as harsh disciplining techniques or punishment, as a response towards challenging child behavior or because they felt stressed-out. However, these parents also mentioned that they realized that these techniques often had the opposite effect and even resulted in more behavior problems, because their child was not able to link the punishment to its actions or because the behavior was not intentional. Parents of children with ASD also described unsuccessful experiences when stimulating their child’s social development (e.g., inviting peers at home, encouraging their child to start a new hobby), because their child felt overstimulated, misunderstood, or got into a conflict. A quarter of the parents raising a child with CP also described feeling frustrated or tired to motivate their child to engage in therapy, to do (daily) exercises, or to use assistive devices or night orthoses because their child found it monotonous, redundant, or even painful. Parents of children with DS especially felt uncertain to give their child more independence because they worried that something might happen to their child.

Within each group, parents also described struggles to be responsive towards their child’s needs. For parents from the reference group, these struggles especially occurred when their child did not open up about peer-related issues that made the child feel sad or excluded (e.g., feeling insecure, an unanswered crush, bullying).

As a parent, I find that very hard to deal with. Because you know, adolescents, adolescent girls, they can be very hard on each other. She has to solve those things for herself, while I try to give a little guidance, but it’s very difficult to get a grip on that. (Mother of J., girl without any known disability)

About a quarter of the parents raising a child with a NDD mentioned they felt uncertain or powerless in how they could support their child in the process of accepting their disability and its consequences. These parents stated that their children became more aware of their own disability during puberty as they increasingly started to compare themselves with peers and started questioning why they needed additional support or a specialized school trajectory. A number of parents found it difficult to deal with their child’s feelings of “not wanting to be different”, which sometimes resulted in depressive feelings or protest against additional support (e.g., not wanting to wear visual supports such as splits, refusing to participate in therapy). Seven parents of children with ASD hypothesized that their child had a great awareness of “being different” because their child’s intellectual functioning matches that of peers without ASD or because their child is highly intelligent. The majority of parents raising a child with ASD also mentioned struggles to act responsively when they were confronted with challenging child behavior (e.g., aggression or withdrawal) or felt uncertain about whether their child’s behavior related to the child’s personality or was rather disability-specific.

Sometimes it’s difficult to distinguish: “Is this about the character? Is it autism? Is it about temperament?” A mixture, I think, as within every person, and hence also in children with autism. (Mother of B., boy with ASD)

Some parents of children with CP and DS found it especially hard to be responsive towards their child’s feelings and thoughts when their child was limited in their verbal and/or nonverbal communication.

Concerning competence-supportive parenting behaviors, several parents in each group reported challenges in setting clear and attainable boundaries. For parents from the reference and the ASD-group, this was mainly related to activities such as doing homework or using electronic devices. More specifically, whereas 17 parents from the reference group struggled to limit the use of mobile devices and social media, eight parents of children with ASD worried about their child’s excessive gaming behavior. Additionally, parents of children with DS described struggles relating to their child’s “excessive social behavior”. For example, some parents talked about worries they had about their child interacting “inappropriately” towards strangers. Parents of children with a NDD described additional challenges in being stringent since they acknowledged their child’s daily and intensive efforts to keep up with the demands of society. For instance, the majority of parents raising a child with ASD indicated that their child often felt overstimulated or frustrated after a day at school, because he/she pushed him/herself to act “socially-desirable” (e.g., being social, achieve high grades) or to prevent exhibiting stereotype behaviors. Consequently, some parents “allowed” their child to release their tensions in a safe home environment, through tantrums or “wild” behavior. Similarly, some parents of children with CP mentioned they sometimes “took over” to offer their child some breathing space although they knew their child was able to do a certain task independently.

Relying on need-supportive parenting

Across groups, many parents described competence-satisfying experiences when they were able to encourage their child’s autonomy, by creating an open atmosphere, fostering their child’s skills, or including their child in decision making. For about two-thirds of the parents raising a child with ASD, it was vital to offer their child a meaningful rationale (e.g., explaining the causes and consequences of people’s actions, clarifying social rules) to facilitate their child’s understanding of the world and to lower barriers for interaction with others.

Across all groups, parents tried to support their child’s need for relatedness by making their child feel secure and loved. To do so, they offered warmth, tried to be emotionally and physically present, or responsive towards their child’s feelings. Several parents indicated that, over time, they felt more competent because they were able to better read their child’s emotional state, recognized subtle indications of relatedness, or found other successful ways to communicate with their child (e.g., through body language, gestures, visualizations).

I think he understands that I understand him. We have like an unspoken bond, he doesn't have to explain things in so many words. I will notice if something is wrong. (Mother of S., boy without any known disability)

One-third of the parents raising a child with a NDD also mentioned they intentionally payed more attention towards their child’s socio-emotional functioning, instead of their child’s chronological age to better tailor to their child’s needs and living environment. Parents of children with ASD even proactively tried to avoid stressful situations or reactively stayed calm to regulate their child’s emotions, for example with “emotion thermometers” or visualizations, when their child felt overstimulated. Seven parents of children with ASD also mentioned that they intentionally underlined their child’s positive behavior, regardless of how small these positive actions appeared to be, since their child already faced a lot of remarks during the day due to non-intentional negative or “inappropriate” behaviors. For parents of children with DS, being patient was a vital factor in their life as they acknowledged that their child needed more time and repetition to understand things or to reach certain milestones.

Across all groups, many parents tried to support their child’s need for competence by providing structure, clear communication and rules, and creating a context in which their child had possibilities to experience success. Half of the parents from the reference group felt proud and respected when they were able to set clear rules and their child adhered to it. For several parents of children with ASD, it was especially important to provide structure and predictability, through clear daily routines, visualization, time schemes, and consistent rules, to relieve stress in their child and to facilitate smooth family functioning. Parents of children with a NDD also consciously formulated achievable goals or adjusted tasks according to their child's abilities so that it was more feasible for the child to meet them. As several parents of children with CP often received a negative or uncertain prognosis about their child’s developmental possibilities, certain successes or achievements (e.g., being able to ride a bike, talking clearly) felt very rewarding and strengthened the parents’ belief in themselves and their child.

Integration of the Parental Role: Struggling to Accept Versus Adjusting Aspirations

Across groups, parents’ perspectives indicated that becoming a parent changes one’s identity. For about one-third of the parents raising a child with a NDD, the process of accepting “being a parent of a child with a disability” affected their feelings of competence. Whereas some parents were confronted with ongoing struggles in their new parental role, many parents described feeling satisfied about the new objectives they had about themselves, their child, and family life.

Struggling to accept

About one in five parents of children with a NDD reported ongoing difficulties in accepting their parental role because they felt guilty (e.g., due to difficulties during the delivery process) or sad about giving up future aspirations for themselves (e.g., traveling, professional career) or their child (e.g., living independently, having a family). Some of these parents even felt disenfranchised because they were “stuck” or “forced” into a certain parenting role, which they did not want or which felt unnaturally (e.g., providing lifelong intensive care, being very structured, overprotective, disciplining).

He makes me being a mom that I actually don’t want to be. I have to keep setting boundaries all the time and play the referee in different situations. It made me change as a person (...) I dreamed of a harmonious family. For a long time, I have blamed him a bit for the fact that he is what he is, which kept my life from going the way I wanted it to. (Mother of J., boy with ASD)

Saying goodbye to a future perspective is the hardest part. My son is going to make his way, he will get married, have children, will be able to live alone. With her, I had the same hopes until she was 5 to 6 years old, but then, every day again you think: that is no longer possible, and that is no longer possible, and that won’t be the case either. Every time it’s just saying goodbye to ordinary things. (Mother of J., girl with CP)

Adjusting aspirations

The majority of parents raising a child with a NDD mentioned they were able to let go of certain aspirations and created adjusted expectations for themselves and their family life. Consequently, they felt more confident about their role as a parent and their parenting processes. Several parents of children with a NDD mentioned that the time and context where they received their child’s diagnosis played a vital role in doing so. For many parents of children with ASD, the diagnostic process was complex, emotionally exhausting and time-consuming, and encompassed feelings of not being heard or taken seriously. For several of these parents, the ASD-diagnosis felt as a relief and strengthened their position as a parent, since it provided an “explanation” or “guide” for the experienced difficulties and how to handle them, and assured an “entrance ticket” for professional support.

Our eyes really opened up because of that diagnosis and by actually delving into it. Doing so, we understand how he thinks and why he thinks like that. And that is very instructive. (Mother of S., boy with ASD)

Parents of children with CP and DS mentioned that their acceptance process started quite early as the diagnosis was often given quite shortly after their child’s birth, which gave them more time to process their living situation (up to the time of the interview). Parents who consciously chose to raise a child with DS after prenatal screening results, described less feelings of loss and less clear expectations about their parental role or future objectives.

External Support: Facing Versus Overcoming Barriers

Although parents from each group described competence-related experiences regarding the provision of external support, this theme was more prominent among parents raising a child with a NDD.

Facing barriers

Especially parents of children with a NDD described practical (e.g., transportation, combination with other tasks), financial (e.g., expensive consultations), and structural barriers (e.g., waiting lists, exclusive school trajectories, legal care provisions) in providing support tailored to their child, which made them question their competence as a parent. Some parents specifically described feelings of stress and uncertainty about choosing the “right” school trajectory (e.g., regular or specialized) or finding solutions for their child’s enduring medical or emotional problems (e.g., eating, sleeping, anxiety problems). Six parents of children with CP even felt powerlessness or guilty when they were not able to ameliorate the physical and emotional pain of their child after medical procedures or while wearing devices such as splints.

I still feel “If only I could take over”. Very often I would shed a tear. Why did that have to happen to her? I would much rather have it happen to me, but unfortunately, we cannot change that. (Mother of L., girl with CP)

Overcoming barriers

In each group, several parents described feeling competent when the support they organized paid off and helped their child move forward in life. Whereas parents from the reference group especially appreciated the support from school or youth movements, parents of children with a NDD mainly described competence-satisfying experiences concerning professional care providers. For many of these parents, different kinds of external support not only stimulated their child’s development but also – and many parents emphasized this as most important – it gave them some time to breathe. Parents of children with ASD especially felt strengthened when counseling at home helped them to creatively look for solutions or to better understand challenging child behaviors.

The Future: Uncertainty Versus Confidence

Although especially parents of children with a NDD described feelings of uncertainty about their child’s future, in each group, several parents also mentioned feeling confident and positive about the future of their child.

Uncertainty about the future

Whereas parents from the reference group especially worried about their child’s schooling and ability to stand up for themselves, parents of children with a NDD expressed uncertainties in diverse domains, such as their future supporting power (e.g., whether they would keep up taking care of their child), their child’s social-communicative or physical development (e.g., making friends, taking public transportation independently), social relations (e.g., having a partner or family of their own), future career (e.g., having a job), and the management and continuity of adjusted care for their child (e.g., housing, education, financial support) especially when the parent would pass away. Parents of children with CP expressed the most worries about the future and six parents even described “the lifelong uncertainty and its responsibility” as the greatest challenges in raising their child.

Confidence in the future

Notably, in each group, several parents were convinced that their child would find his/her way in life. Most of these parents tried to live in the moment (e.g., to take every day as it comes) and avoided worrying too much. Although this theme was mentioned in each group, it was more prevalent among parents from the reference group.

Discussion

The current qualitative study examined the experiences of parents raising a child with ASD, CP, DS, and without any known disability, analyzing parents’ spontaneous responses to two open questions. The SDT-framework (Deci & Ryan, 2000) was applied to structure parents’ perceived challenges and opportunities in their need for autonomy, relatedness, and competence. By differentiating between these three needs in each group, we aimed to identify both overarching and group-specific (sub)themes in order to provide guidelines for parenting support and to enhance parents’ well-being. Moreover, the innovative comparative design allowed us to process and compare a large amount of data in a similar way, and to compare parents’ perspectives across three diverse NDDs and a reference group. However, these group differences must be interpreted carefully and, above all, must be regarded as tentative since the qualitative comparison is confined to the interpretations of the research theme. Nevertheless, the prominence and saliency of themes seemed to differ across groups.

Similar Experiences Across Groups

In line with SDT’s universality claim (Deci & Ryan, 2000), all parents stated that raising a child entails both challenges and opportunities with regard to their need for autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Importantly, the different groups reported a similar amount of need-satisfying experiences. This observation highlights that although parents of children with a NDD face regular challenges, they also experience a broad array of meaningful positive experiences. Moreover, parents showed to be eager to mobilize resources to help their child, and resilient to adjust their hopes and aspirations for themselves and their family (Van Riper, 2007). Also relatedness-satisfying experiences regarding the parent–child relationship were equally distributed across groups. This finding corroborates with previous research indicating that the challenges associated with a child’s disability can also make the parent and child grow closer to each other (Björquist et al., 2016; Ooi et al., 2016). Despite studies suggesting that partner relationships among families of children with a disability can be more strained (Davis et al., 2010; DePape & Lindsay, 2014; Myers et al., 2009), the findings in this study revealed no clear group differences in relatedness frustration regarding the partner relationship. With regard to parents’ need for competence, parents from each group mentioned feeling proud or strengthened when their parenting behaviors matched their child’s needs, indicating that parents' competence-related experiences and parenting behaviors are highly intertwined (Dieleman et al., 2018; Dieleman et al., 2019). Interestingly, parents’ spontaneous speech samples demonstrated that parents from each group relied on similar parenting behaviors to support their child’s needs. For instance, in each group several parents tried to support their child’s need for relatedness by offering warmth, showing empathy, and being emotionally and physically present. This finding corroborates with the results from a recent quantitative multi-group study among parents raising a child with ASD, CP, DS, and without any known disability, demonstrating minor differences in parent-report parenting behaviors across groups (De Clercq et al., 2019).

Group-Specific Findings

In addition to the shared experiences across groups, this study sheds light on three themes for which parents’ need-related experiences varied according to the presence or type of the child’s disability.

Unique and Changing Parent–Child Relationships

While the study findings support the idea that parents of children with a NDD experience more challenges in accomplishing reciprocal parent–child relationships (Van Riper, 2007; Watson et al., 2011), these challenges appeared to differ in content and intensity according to the child’s type of disability. The “challenging” parent–child relationship within the ASD-group corroborates Myers et al. (2009)’s qualitative study where parents of children with ASD described the impact of their child’s disability on their own and families’ life as “my greatest joy and my greatest heartache”. In other words, whereas many parents acknowledged the challenges of raising a child with ASD (e.g., stress, dealing with behavior problems, social isolation), many also found positive meaning in life (Myers et al., 2009). The “intense” parent–child relationship among CP-populations has been related to the rigorous support and adaptions these parents have to make, which felt intense but also caused parents to spend a lot of time with their child and to feel highly involved and important in their child’s life (Dieleman et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2010). The observation that many parents of children with DS described their parent–child relationship as “warm” and the finding that parents from the DS-group reported less need-frustrating experiences compared to the other NDD-groups might tentatively relate to what has been described as the “Down syndrome advantage” (Skotko et al., 2011; Stoneman, 2007). Following this idea, these parents’ reports of less need-frustrating experiences could be attributed to more positive personality traits and fewer maladaptive behaviors among children with DS compared to children with other developmental disabilities (Stoneman, 2007). Moreover, the positive stigma about children with DS (e.g., kind, loving, affectionate), might facilitate parents’ experiences with the environment (Hodapp et al., 2019). However, both this study and previous research emphasize that the struggles of these parents should not be underestimated, as these parents also clearly describe challenges related to their personal and social life, and the broader environment (Povee et al., 2012).

Furthermore, since the study included parents of children with a specific age range (i.e., emerging adolescence), the findings revealed some development-specific experiences. For instance, parents’ experiences demonstrated a dynamic character, showing that parents’ perspectives are strongly embedded in a specific time frame of changing parent–child relationships. Among parents raising a child with a NDD, the child’s transition into adolescence encompassed additional challenges as the child’s social-communicative, physical, or cognitive abilities hindered opportunities to disclose changes that the adolescent encountered or to solicit advice, information, and comfort from their parents. Especially within families raising an adolescent with CP, the adolescent’s increased strive for independence showed incompatibility with the strong physical dependency and hence might complicate their child’s adherence to therapy and daily exercises (Holmbeck et al., 2002). In line with previous research, our findings demonstrated that during the transition from childhood to young adulthood, parents of children with a NDD might experience more feelings of grief because they realize that certain milestones will not be reached or because it is hard to support their child in dealing with “being different” (Hamilton et al., 2015).

Facing Barriers to Belong

In line with previous studies (e.g., Altiere & von Kluge, 2009; Cuskelly & Gunn, 2003; Dieleman et al., 2019; Myers et al., 2009; Sipal et al., 2010; Skotko et al., 2011), our findings indicated that raising a child with or without a NDD impacts parents’ relationship with significant others, namely the child’s sibling(s), their partner, friends and family, and the broader society in both positive and negative ways. Although parents’ perspectives were quite similar concerning the sibling and partner relationship across groups, parents of children with a NDD mentioned consistently more relatedness-frustrating experiences regarding their social context or relationship with care providers. In line with previous studies, especially parents of children with ASD and CP mentioned they lacked social contacts due to the intense care for their child and practical difficulties limiting their possibilities to join activities with friends or families (Alaee et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2010). Whereas these social contacts were additionally hampered due to disagreements about how to deal with challenging behavior in children with ASD (Myers et al., 2009; Woodgate et al., 2008), parents of children with CP were confronted with more structural difficulties (e.g., social events that are not wheelchair-accessible) (Dehghan et al., 2015).

Also, the (in)visibility of the child’s disability played a vital role in parents’ and children’s interactions with the broader environment. Although experiences of social exclusion or stigmatization differed according to the child’s type of NDD, parents from each NDD-group described painful experiences (e.g., being stared at, pitying looks, whisperings, or laughter) indicating that these families often have to deal with judgments from others (Lalvani, 2015; Ludlow et al., 2011). These experiences also corroborate previous research among parents raising a child with ASD (Gray, 2002), indicating that the majority of these parents experience both felt (i.e., feelings of shame or the fear of rejection) and enacted stigma (i.e., instances of overt rejection or discrimination experienced by stigmatized individuals). It is also interesting to notice that although parents of children with a NDD described more empowering experiences than parents from the reference group, these experiences might be particularly motivated by confrontations with societal boundaries or deficit discourses (e.g., exclusion, injustice, stigma, accessibility, ethics of prenatal screening), instead of being volitionally motivated. Within these confrontations, parents take on a “battler role”, fighting for equal rights regarding diversity and support (Altiere & von Kluge, 2009; Van Hove et al., 2009).

“Being a Parent”: a Transformative Process

Parents’ perspectives highlighted that parents grow and evolve in their position as a parent. For parents of children with a disability, this transformation could not be reduced to “learning to live with it”, but included a set of experiences and conditions. According to Isarin (2004), conditions for such a transformation are: the ability to accept the child as it is while intending to make the best of it, the conviction that this parenthood is meaningful, building up confidence, and the ability to live with uncertainty. Our findings align with these conditions and even indicated that this process of transformation also varies depending on the specific disability of the child, the time and circumstances of the diagnosis, and the support from family, friends, and care providers (Isarin, 2004; Schuengel et al., 2009). Moreover, this process of transformation showed to be highly intertwined with how parents perceived their parental role and identity. Several parents seemed to internalize their parental role as parents’ values, beliefs, commitments, and behaviors became personally endorsed and aligned with the self (Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2011). In NDD-research, this process has been related to Bowlby (1980)’s concept of resolution, since a child’s NDD-diagnose may pose similar challenges of reorganization and integration for parents as experiences of loss or other psychological trauma. In line with previous research among parents of children with CP (Schuengel et al., 2009), our findings suggested that many parents resolved their reactions to their child’s diagnosis at the time when their child reached adolescence, while others still expressed unresolved reactions indicated by dissatisfaction about their current life or retainment to unfulfilled dreams.

Implications for Research and Practitioners

The comparative design of this qualitative study provides a more nuanced and contextualized perspective on parents’ experiences, hence enhancing rigor, credibility, and reliability of the findings (Morse, 2015). Using SDT as a theoretical framework also contributed to a systematical comparison of experiences across diverse groups, while also taking into account a more balanced approach on parenting (i.e., examining both challenging and rewarding experiences). Additionally, our findings support that the collection of spontaneous speech samples holds potential as a brief, time-efficient, yet rich informative tool for indexing naturalistic parental experiences in both research and practice (Sher-Censor, 2015). Also, since the method can be effectively administered over the phone and a limited amount of time is needed to administer the speech samples, the FMSS-method encompasses some practical benefits to quickly assess where the greatest needs and strengths are situated within a family. Moreover, the findings based on this innovative method are similar to findings that emerge from small-scaled in-depth-interview studies but allow to meaningfully integrate information from much larger samples.

In addition to research implications, this study implies multiple lessons on how practitioners and policymakers can help to better support parents’ needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence while raising a child with a disability. First, the prominence of autonomy-satisfying experiences among parents raising a child with a NDD supports an approach in practice where parents’ positive experiences and the “things that go well” are explicitly acknowledged and reinforced. Moreover, these experiences can provide valuable insight into the factors that enhance but also impede parents’ resilience. For instance, when parents indicate a need to invest more time in their own interests and needs, care providers could organize (specialized) respite care, after-school care, or at-home support to give parents more “breathing space” (Guyard et al., 2017). Second, parents felt especially connected with care providers who treated them as equals and when caregivers were attentive and non-judgmental, noticed and valued the strengths of their child, and were genuinely interested in the well-being of the child (Frye, 2016). During the whole process of diagnosis, assessment, and rehabilitation, care providers must recognize parents as valuable contributors. Moreover, they should ensure transparent and open communication since these experiences form parents’ trust and confidence in professional support after the diagnostic process (Boshoff et al., 2019). Furthermore, it seems important to “zoom out” during parent support and acknowledge the value of parents’ relationships with important others: their partner, other children, friends, relatives, and the broader society. Previous studies also demonstrated that for parents raising a child with a disability, the amount of support from others, such as relatives, friends, neighbors, and care providers, is crucial for their family quality of life (Brown et al., 2003; Steel et al., 2011). When parents need a new source of relatedness, care providers could, for instance, facilitate contact with parent-to-parent peer support groups, which might also increase parents’ coping abilities and decrease parental stress (Bray et al., 2017). Third, to increase parents’ feelings of competence, care providers should acknowledge parents’ efforts and perseverance, their expert position about their child, and should provide information and guidance for navigating the complexity of care trajectories (De Belie & Van Hove, 2005; Frye, 2016). Setting clear boundaries regarding the use of electronic devices might also be an important theme in parent support. Especially among children with ASD, excessive gaming behavior and the many concerns of parents related to this topic requires further attention (Mazurek & Wenstrup, 2013).

Moreover, this study highlighted unique insights into the challenges that parents of children with a NDD face while supporting their child’s needs. For instance, although parents of children with a disability wanted to be need-supportive, the child’s attention span, communication, motor, or sensory difficulties, or “reduced readability” (i.e., the child shows less initiative to signalize needs or to engage in social relationships) might interfere to do so (Gilmore et al., 2016; Hodapp et al., 2019). Therefore, parents might struggle to estimate the time, amount, and specificity of support their child needs or might feel they have to be more directive or constantly supervising to guarantee their child's safety (Gilmore et al., 2016). Also, as several parents indicated they struggled to interpret their child’s behavior, it might be valuable to support parents to understand the functionality of their child’s behavior and reflect on their own attribution style. In their book “Positive Discipline for Children with Special Needs”, Nelsen et al. (2011) even argued that parents should be supported to distinguish innocent behaviors associated with the child’s disability from deliberately misbehaving, as the misinterpretation of innocent behaviors may elicit new challenging behaviors.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research