Abstract

Using the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data, we examine the relationship between family decision-making power and women’s marital satisfaction. Interestingly, this paper reveals that overall, there is a negative association between women’s family decision-making power and marital satisfaction. However, some heterogeneities exist: the negative association is found among women with less education (income), and constrained by Confucian family ethics, but no association is found for women from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. Women from more traditional and economically disadvantaged backgrounds are conflicted by the prospect of breaking existing social norms designated for them. Therefore, when operating outside the traditional norms to become family decision-makers, their marital satisfaction is reduced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Family Decision-Making Power and Women’s Marital Satisfaction

In contemporary China, two very different forces influence women’s attitudes about gender and the behavioral adjustments made by women to improve their well-being. The first force is “socioeconomic transformation.” With this process, women increasingly reject labels such as dependency and obedience; instead, they proactively go out of their homes and work in offices, universities and other settings to realize economic freedom and self-worth (Pratten, 2013). Women do not rely on their husbands for their own well-being, but aim to construct a new and more equal gender identity. They start participating in important socioeconomic affairs that are inconsistent with the traditional role of assisting their husbands. Overall, women attain independence from their husbands financially and rid themselves of emotional dependence on their husbands. Such changes have enhanced women’s opportunities outside the home; thus, they have more bargaining power in the family than ever before. Many women acquire the confidence to take a decisive role in important family affairs, such as household investments. The pro-women family power relation driven by socioeconomic transformation is found to improve the welfare of women and children due to more control over resource allocation. Consequently, women’s satisfaction in the marriage will keep improving to some extent with increasing bargaining power.

Meanwhile, there is another competing force described as “Confucian family ethics,” which sets various barriers to women’s development. The written rules of Confucianism limit women’s power severely, and require women to be obedient to men throughout their lives (Turner & Salemink, 2015). Formally, men are the heads of the family unit and exercise legal power over the women and children in the household. Women typically do not have formal roles in Confucian life outside the home, and their lives are controlled by male kin. Accordingly, they must defer to the wishes and needs of closely-related men in the family, e.g., fathers and husbands. In Confucianism, women are mostly restricted to private, separated space (Valutanu, 2012), which denies women access to education and public activities. Thus, for the vast majority of Chinese women, belonging to a home is the only means of economic survival. Though China’s feudal society no longer exists, traditional modes of thinking are difficult to eliminate. Such a social environment has long constrained women’s daily behavior and role positioning within the family; thus, they have formed inherent beliefs and intuitions about certain behaviors since birth. The psychological expectations regarding a couple’s family roles and responsibilities shape the widely accepted gender role norms. Therefore, under Confucian family ethics, when traditional roles are adhered to, women’s marital satisfaction will thereby increase. In contrast, any deviation from the accepted social arrangement, such as the case wherein women cross the social category to play a decisive role in important family affairs, will negatively affect their marital satisfaction.

As shown above, two competing forces simultaneously influence family decision-making power and women’s marital satisfaction; however, there is a lack of literature in China to determine the stronger force of the two. Given this, the paper employs the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data to investigate whether or not women’s control over family decision-making power improves their marital satisfaction. In the context of China, some contributions made in the paper are summarized as follows: first, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical paper to rigorously investigate the relationship between family decision-making power and women’s marital satisfaction in China with its rapidly transitioning socioeconomics. We found that women’s decisive role in family affairs has a negative effect on their marital satisfaction even if the socioeconomic transformation force empowers women greatly. Second, we detected the traditional gender role attitudes in engendering the negative marital satisfaction effect of women’s family decision-making power, especially for those women with a lower socioeconomic status and constrained by social norms. Specifically, we found that women with less education and income, and constrained by traditional gender norms, consistently adhere to mainstream gender role attitudes, and are unwilling to be decision-makers in the family. This will help researchers further understand why women’s empowerment in the family might adversely impact their well-being in certain contexts. Additionally, it is worth noting that the heterogeneous effects between women’s marital satisfaction and their family decision-making power across socioeconomic statuses and surrounding environments, might enrich future theoretical analysis.

Our study closely relates to the literature on factors associated with marital satisfaction and marital stability. According to previous research, marital satisfaction is affected by many factors, including sex (Whiteman et al., 2007), age, status of job (Yu & Liu, 2021), number of children (Wendorf et al., 2011), education (Rouhbakhsh et al., 2019), time spent together (Johnson & Anderson, 2013), cultural considerations (Lalonde et al., 2004), trust (Fitzpatrick & Lafontaine, 2017), and personality traits (Sayehmiri et al., 2020). Over recent decades, the impact of marital power on marital satisfaction has been studied in Western countries (Beach & Tesser, 1993; Bulanda, 2011; Leonhardt et al., 2020; Rogers & DeBoer, 2001). In comparison, related topics studied in non-Western countries are still relatively scarce. As of now, no related research has been conducted in the Chinese context despite the occurrence of a huge socioeconomic transformation. Moreover, the findings based on Western countries are generally inconclusive. For example, Sarantakos (2000) found that marital power is not associated with quality of marriage at all; however, Leonhardt et al. (2020) indicated that equality in power relations correlates positively with marital quality among women. The mixed results above suggest that the relationship between martial power and marital quality may not be comprehensive enough; therefore, it is necessary to incorporate other cases, especially non-Western cases for further clarification.

Our work also relates to the literature that investigates how decision-making power in the family is attributed to individual family members. Starting with seminal papers by Chiappori (1988, 1992), the static collective model of household behavior has become the standard paradigm of household analysis. It views households as a collection of different individuals with diverse preferences and endowments, and members negotiate with each other for the sake of a Pareto-efficient intra-household allocation of welfare (Chiappori et al., 2008; Knowles, 2012). However, a static model cannot be used to analyze the evolution of intra-household decision power, given that it cannot take into account the effect of an individual’s current choices for long-term welfare. Considering the drawbacks of the static model, some scholars proposed the influential limited commitment intertemporal collective model to analyze household behaviors in a dynamic environment (Bredemeier et al., 2021; Chiappori & Mazzocco, 2017; Chiappori et al., 2020; Voena, 2015). These papers showed that in contracts with limited commitment, the spouses cooperate without being able to commit to a contingent plan; instead, they can renegotiate the agreement at any time. The optimal household decisions can be obtained by solving a standard Pareto problem with participation constraints that require the expected utility of staying married to be greater than or equal to that of divorce (Mazzocco, 2007; Mazzocco et al., 2014). Thus, in the absence of commitment, household decisions depend on the decision-making power in each period, which is determined by the outside options of members (Safilios-Rothschild, 1970; Treas & Kim, 2016). In this regard, external shocks due to education, income, inheritance rights, social capital, etc., will dynamically change the relative bargaining position of members in family decision-making process (Agarwal, 1997). Besides this, some scholars suggested that social norms, beliefs, divorce laws, and in particular, gendered institutions will also impact family members’ options outside the home (Mabsout & van Staveren, 2010; Voena, 2015).

In the paper most closely related to our work here, Bertrand et al. (2015) claimed that traditional gender identities cause couples to make efforts to avoid having a female primary earner. However, if the wife earns more than the husband, empirical results showed that the spouses tend to be less satisfied with their marriage, more likely to report that the marriage is in trouble, and are more likely to divorce. Our finding of a negative effect of women’s decision-making power on their marital satisfaction is of major importance for this strand of literature. While starting from family decision-making power, we again confirmed the claims of Bertrand et al. (2015) that any deviation from traditional gender identities may hurt marriages to some extent even in a transitioning society.

The remainder of this paper is arranged as follows. The second section provides an overview of Confucian family ethics and gender roles in China. The third section displays variables, data, and summary statistics. Econometric analysis and its interpretation are given in the fourth section, and the last section discusses and concludes the study.

Confucian Family Ethics and Gender Roles in China

In the Confucian tradition characterized as patriarchal and patrilineal, women were placed at a severe social disadvantaged position relative to men (Thornton & Lin, 1994). Some argue that male-centered Confucianism has been the primary reason for the low social status of women in China, since it became an official ideology of the state in the Han Dynasty (B.C. 207–A.D. 202) (Mak, 2013). Traditionally, under Confucianism, women were asked to follow “the Three Obediences and Four Virtues,” which is a set of moral principles and social code of behaviors specifically for women. The three obediences require women to comply with men without exception throughout their lives. That is, a female should obey her father before marriage, obey her husband during married life, and obey her sons in widowhood. The four virtues imposed on women reinforces physical charm, fidelity, propriety in speech, and diligence and thrift (Cheng, 2008). This set of virtues represents traditional society and the traditional roles of women within that society. Additionally, Confucianism required women not to receive education, not to engage in paid work, to carry on the family line as a mission, and to honor this observance for the entirety of their respective lifetimes (Mak, 2013). Overall, traditional China, as a patriarchal society, regarded men as the breadwinner, decision-maker, and the master of the family, and they were expected to work outside of the house, gain resources for the family to live on, and make a difference in society. By contrast, women were seen as powerless, docile, obedient, and inferior to men for their whole lives (Turner & Salemink, 2015; Valutanu, 2012). Once a woman married, her only identity was as a wife and the only right place for her was her husband’s family (Turner & Salemink, 2015). Her domestic role of supporting and protecting her husband’s family became the only criterion for measuring her success in life. The imbalance of power between a man and a woman was seen as normal and fundamental within a family. The Confucian doctrine of gender hierarchy defined women’s and men’s differential rights, positions, and roles within a family for more than two thousand years.

Since the collapse of the Qing dynasty (the last imperial dynasty) in 1911, social norms concerning gender roles have changed remarkably. The May Fourth Movement during the 1910s and 1920s challenged the gender stratification of Chinese society in an open and systematic fashion, and challenged the patriarchal family in favor of individual freedom and women’s liberation. The Movement criticized classical Confucian traditions and promoted a new Chinese culture based upon progressive, modern, and western ideals. The activist advocated equality between women and men, free love and marriage, educational opportunities for women, labor force participation of women, and fundamentally, women’s emancipation.

The May Fourth Movement however, included and was effected by only a small number of urban and elite women (Li, 2000). It was after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 that dramatic changes took place that had a strong impact on the lives of hundreds of millions of Chinese women. The new government made a firm commitment to guarantee the equality between women and men, as reflected in the famous quotation “women hold up half the sky”. The New Marriage Law in 1950 abolished feudal marriage (e.g., bigamy, concubines), and implemented a marriage policy of monogamy and equal rights between men and women. This law also explicitly granted women the freedom to participate in the labor market and pursue a formal education. Since the 1950s, enormous progress has been made in increasing women’s economic opportunities and education level. By 2017, females accounted for 55% of college graduates, whereas males accounted for only 45%, and the percentage of female students is 10% higher than that of male students (Wang et al., 2019). According to the World Bank statistics, female labor force participation (FLFP) of China is above 62%, far higher than 46% global FLFP in 2020. Additionally, women play important roles in significant leadership positions, and the gender wage gap in certain occupations is also gradually narrowing (Bian et al., 2015).

Despite these substantial improvements, traditional notions and practices concerning gender relations and the family have persisted. Women still bear a heavier burden of housework relative to men, e.g., caring for children and the household (Xie, 2013). Men continue to dominate in core political arenas, and women are often underrepresented in various leadership positions. Female labor force participation has followed an inverted U-shaped trajectory: it started to fall in the 1980s at its peak (84% FLFP) along with the historic economic reform, accelerated its decline in the late 1990s (72.60% FLFP in 1995) during the downsizing of state-owned enterprises, and continued to drop to 62% in 2020. Gender gaps in pay have again widened in many sectors (Ge & Yang, 2014), gender discrimination in the labor market is widespread, and there is evidence of a worsening bias in views about women’s right to work and leadership in the workplace. In decades of major structural changes in the economy, a number of China’s earlier achievements in gender equality have gradually eroded. Overall, as China reforms socioeconomically from a centrally planned regime to a market-determined system, traditional views and practices regarding gender relations and division of labor within the family have rebounded.

Although Chinese society has undergone unprecedented transformation in many dimensions, women fall far behind their male counterparts economically and politically. An egalitarian gender identity remains under construction in the complex interplay and interaction between modern ideas and traditional culture. The persistence of traditional social and gender identity norms still exists in Chinese society. Thus, it is of practical importance to study to what extent Confucian family ethics determine the family structure and women’s well-being.

Variables, Data, and Summary Statistics

Variables

The dependent variable, that is, \(M\_satisfaction\) is defined as the degree to which an individual is satisfied with their marriage. The respondent chooses from five options: very unsatisfied, quite unsatisfied, neutral, quite satisfied, and very satisfied. The corresponding values range from 1 to 5. The larger the value, the more satisfied with her marriage a woman is found to be.

The independent variable, that is, \(Decision\) is defined as women’s family decision-making power and is assessed by who takes charge in five important family affairs; these include household expenditure allocation, household savings and investment, buying a house, children’s education, and high-priced consumer goods. If a particular matter is decided by the wife, it is assigned with 1, by the husband, − 1, by co-negotiation, 0. Then, the scores of the above family affairs are added to construct a comprehensive variable that reflects women’s decision-making power in family affairs. The higher the value, the greater women’s decision-making power in the family is found to be. Additionally, we also employ the principal component analysis (PCA) method to extract a principal component from the above five dimensions. We name the new indicator as \(PCA\_Decision\), and it reflects the women’s family decision-making power too. According to our calculations, the correlation between \(Power\) and \(PCA\_Decision\) is as high as 0.99; thus, the indicators measured by the two methods are highly consistent. Based on the above consideration, we only use the variable of \(Decision\) to carry out the following empirical analysis.

Based on previous empirical studies, some possible confounding factors are controlled. Among them, female characteristic variables include household registration (\(Urban\), if urban household registration, \(Urban\) = 1, otherwise = 0), religious belief (\(Religion\), if a believer, \(Religion\) = 1, otherwise = 0), years of education (\(Education\)), annual income (\(Income\), unit: ten thousand Chinese renminbi, RMB), interpersonal relationship (\(Relation\), 0–10, where a greater value indicates a better interpersonal relationship), age (\(Age\)), status of job (\(Employment\), if employed in the past week, \(Employed\) = 1, otherwise = 0), type of job (\(Jobtype\), 0–3, if unemployed, \(Jobtype\) = 0, agriculture-related job, \(Jobtype\) = 1, employed in companies, \(Jobtype\) = 2, entrepreneurship and self-employed, \(Job\_type\) = 3), the frequency of eating together with family members per week (\(Eat\_together\)). In addition, existing studies have shown that personality traits explain a large degree of individual subjective well-being (Diener, 1984; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005); so, the factor of “The Big Five” personality is added to the model. Given data availability in the CFPS 2012, Neuroticism is measured with the following four items: I feel depressed; I feel low; I feel afraid; and I feel sad; Agreeableness is measured by the following two items: I think people are unfriendly to me; I do not think people like me; Conscientiousness is assessed by the following item: I have difficulty concentrating on doing things. Each of the items corresponds to the following four options: most of the time, often, sometimes, and rarely with assigned values of 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. Then, a variable reflecting individual personality (\(Personality\)) is constructed by summing the scores obtained from each item. The greater the value is, the higher the non-cognitive skills.

Meanwhile, according to Wang et al. (2019), individual well-being has a significant spillover effect within the family, so we also control some variables at the family level: the number of children (\(N\_Child\)) and the social status of the family (\(Family\_status\), 1–5, where a larger value indicates the higher social status of the family). Additionally, the standard theory of family decision-making suggests that marrying a high-value (e.g., well-educated, physically attractive) husband increases a woman’s marital satisfaction and, de facto, decreases her influence in family decision-making. So, to distinguish between the effect of household decision-making power and that of the husband’s perceived value on women’s marital satisfaction and decision-making power, we control the husband’s characteristics. The variables include the husband’s years of education (\(S\_Education\)), annual income (\(S\_Income\)), interpersonal relationship (\(S\_Relation\)), personality traits (\(S\_Personality\)), age (\(S\_Age\)), status of job (\(S\_Employment\)), physical appearance (\(S\_Appearance\), 1–7, where a larger value indicates a more attractive appearance)Footnote 1 and household labor contribution (\(S\_Housework\)). Considering that factors such as the external environment will also affect individual well-being, variables related to the environment are controlled. They include the average level of trust among neighbors in the community \((N\_trustc\), 2.3–5, where a larger value indicates that there is a high level of trust between neighbors) and gender role attitudes in the community (\(Rolec\), 2–10, where a larger value indicates that the community emphasizes traditional gender role attitudes). Additionally, the paper adds provincial dummies to control the impact of regional heterogeneity.

In the heterogeneity and mechanism analysis, the variable of gender role attitudes (\(Role\)) is worth noting. It is measured by the two statements: (a) men should focus on career, women should focus on family, and (b) marrying well for women is better than financial independence. The respondent can choose from five options, between 1, which represents strongly disagree and 5, which represents strongly agree. Then, the variable of gender role attitudes is constructed by summing the scores of the two statements. The higher the value, the more attitudes are inclined to the traditional gender role.

Data Source

The data used in this paper are from CFPS. It adopts a stratified and multi-stage sampling method to collect the data. As a nationally representative survey, the CFPS captures recent changes in social, economic, and demographic features in China (Xie & Lu, 2015). The baseline survey, launched in 2010, surveyed 14,789 households, 635 villages, 162 counties, and 25 provinces in China (Xie & Hu, 2014). Afterwards, the organization conducts a biennial follow-up survey by tracking family members, with an average response rate of about 79%. It includes individual, family, and community-level information.

Although the CFPS longitudinal survey data was updated in 2018, only the 2014 round of CFPS collected the necessary information for our empirical analysis, that is, individual marital satisfaction and gender role attitudes. Therefore, this paper mainly uses the CFPS 2014 data to study the impact of family decision-making power on women’s marital satisfaction. Although the time effectiveness of the CFPS 2014 is not ideal, the important topic examined in this paper remains an unstudied academic field in China. No previous relevant research has applied a rigorous empirical test to this topic; so, the related findings in the paper will form the basis of further research in the future.

Summary Statistics

Table 1 lists the summary statistics of the main variables in this paper. We can see that the mean value of \(M\_satisfaction\) is 4.380, suggesting that women in the sample are satisfied with their marriage overall. The mean value of \(Decision\) is -1.170, indicating that only a small number of women are decision-makers of important family affairs. Consistent with the reality of Chinese society, the husband is responsible for major family affairs, while the wife plays the role of supporting her husband. In terms of the external environment, most neighbors show their support for the traditional gender role attitudes. In addition, 45.8% of the women in the sample live in cities, the mean level of education is 5.8 years of schooling, and each family has 1.4 children on average. While making a mean comparison, men generally have more education and income than their spouses. Thus, women have been in a relatively disadvantaged position in terms of human capital accumulation and the job market. As expected, men are somewhat older than their spouses in marriage. All these variables are consistent with the realities of Chinese society in 2014, thus ensuring the representativeness of the sample. The Pearson correlationsFootnote 2 between the independent variable and control variables show that the coefficient of correlation between any two variables is generally less than 0.1. The exception is that a larger coefficient of correlation appears between the wife’s characteristics and the husband’s corresponding characteristics. Specifically, the coefficient of correlation between a couple’s education levels is 0.563, income is 0.374, employment is 0.267, interpersonal relationship is 0.223, and personality trait is 0.469. This reflects the phenomenon of positive assortative matching in marriage in contemporary China. Overall, multicollinearity is unlikely to be a problem in our econometric model.

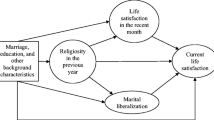

Figure 1 displays the relationship between women’s marital satisfaction and their family decision-making power. It is shown that the wife’s marital satisfaction is lower when her family decision-making power exceeds that of her husband. This suggests a negative correlation between women’s family decision-making power and their marital satisfaction.

Econometric Analysis and Interpretation

Econometric Model

To test the impact of family decision-making power on women’s marital satisfaction, we set women’s marital satisfaction as the dependent variable and family decision-making power as the independent variable. After controlling for some confounders that may affect the relationship between the two variables, we establish the following econometric model to identify the parameters to be estimated:

Where in, \(M\_satisfaction_{i}\) refers to women’s marital satisfaction, \({Decision}_{i}\) is women’s decision-making power in family, and the variables in \(X_{i}\) are possible confounders from three levels. At the individual level, they include individual i’s household registration, religious belief, education, income, interpersonal relationship, personality traits, age, status of job, type of job and the frequency of eating together with family members. At the family level, they include the number of children, social status of the family, and the spouse’s education, income, interpersonal relationships, personality traits, age, status of job, physical appearance, and household labor contribution. At the community level, they include the average trust between neighbors in the community and gender role attitudes in the community. \({\mu }_{i}\) is a random error term. Due to the ordinal nature of marital satisfaction, we use an ordinal response model to estimate the parameters in Eq. (1).

Benchmark Regression Results

Referring to Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004), we first regard \(M\_satisfaction\) to be a continuous variable and use the ordinary least squares (OLS) method as the benchmark regression. After OLS, we employ the ordinal probit model to re-estimate the parameters of interest in Eq. (1). Table 2 reports the OLS and ordinal probit model results. In Columns (1) and (3), we do not control the husband’s characteristics; and in Columns (2) and (4), we control both the wife and husband’s characteristics. The coefficients of \(Decision\) in Columns (1) and (3) are greater in absolute value than those in Columns (2) and (4). This indicates that the husband’s characteristics do affect women’s marital satisfaction. In Table 2, we see that the husband’s interpersonal relationship, age, physical appearance, and housework activities are important determinants of women’s marital satisfaction. So, it is necessary to account for the relation between the husband’s identity and behaviors in women’s marital satisfaction function. Overall, the estimated coefficients of \(Decision\) are all significantly negative. This indicates that the status of being family decision-makers has a negative effect on women’s marital satisfaction.

From the above, we know that the power within the family is also a key determinant of women’s marital satisfaction. Compared with the “socioeconomic transformation force,” the “Confucian family ethics force” determines the marital satisfaction of current Chinese women to a greater extent. It emphasizes the traditional gender division of labor, and the retention and consolidation of husband-supporting and child-rearing patterns in the family, thus, setting up an invisible barrier to the development and empowerment of women (Elam & Terjesen, 2010; Elson, 1999). In the current social context, though women’s socioeconomic status has improved as never before, most of them still find it difficult to rid themselves of the gender role norms of “men being the masters of the family.”

Heterogeneity Effect

The full sample regression results above show that although the socioeconomic changes have empowered women greatly, the gender norms shaped by Confucian ethics have not been shaken and many women continue to support the traditional norms of “men being the masters of the family.” Concerning possible heterogeneity, we next examine the martial satisfaction effects of women’s family decision-making power across subsamples, i.e., socioeconomic statuses and surrounding environments.

Regarding socioeconomic status, we mainly consider two indicators: women’s education and income. In China, less education and income are generally positively associated with a lower socioeconomic status (Lowry & Xie, 2009). First, we divided the sample according to women’s years of education (\(Education\)). In total, four subsamples are generated, which include primary school and below (\(Education\le 6\)), junior high school (\(6<Education\le 9\)), senior high school (\(9<Education\le 12\)), and bachelor degree and above (\(12<Education\)). Then, the ordinal probit model is applied to estimate the effect of women’s family decision-making power. The results are displayed in Table 3. It shows that the coefficient of \(Decision\) is significantly negative in Column (1), but it is insignificant in other columns. This indicates that the negative effect of family decision-making power on women’s martial satisfaction is particularly significant among less educated women. Second, besides education, we further generate three subsamples for heterogeneity analysis according to women’s income. It is defined as a low-income group if a woman’s income is less than the 25% quartile of \(Income\); a middle-income group if a woman’s income is located between the 25% and 75% quartiles of \(Income\); a high-income group if a woman’s income is greater than the 75% quartile of \(Income\). Then, we use the ordinal probit model to estimate parameters of interest. The results are displayed in Table 4. It is shown that the coefficients of \(Decision\) in Columns (1) and (2) are significantly negative at the 5% and 10% levels. Referring to the high-income group, \(Decision\) has negative coefficients in low and middle-income groups. This confirms that the negative marital satisfaction effect of women’s family decision-making power is particularly significant among those women with less income. Overall, we find a negative association of women’s marital satisfaction with their decision-making power among these women with a lower socioeconomic status, but no association for more socioeconomically advantaged women.

Third, we use the traditionalization of community to measure surrounding environments. Its classification is mainly based on the variable of traditional gender role attitudes in the community (\(Rolec\)). When it is less than the value of its 25% quantile, it is classified as a less traditional community; when it is greater than the value of its 75% quantile, it is classified as a more traditional community; when it is between the value of its 25% and 75% quantiles, it is classified as a moderately traditional community. Then, the ordinal probit model is used again to examine the impact of family decision-making power on women’s marital satisfaction. The coefficients of \(Decision\) in Columns (2) and (3) of Table 5 are significantly negative, but is not significant in Column (1). Although setting aside the issue of significance, the coefficient of \(Decision\) in Column (1) shows that family decision-making power has almost zero impact on women’s marital satisfaction. So, the negative marital satisfaction effect of women’s family decision-making power becomes stronger along with the degree of traditionalization of community, that is, in an environment that puts greater emphasis on traditional social norms, women’s marital power will have a more negative effect on their marital satisfaction.

In conclusion, the above results show a heterogeneous effect of family decision-making power across women’s socioeconomic statuses and surrounding environments. Among those women with less education and income, and living in communities that emphasize traditional family ethics, the status of being a family decision-maker will reduce their marital satisfaction significantly.

Transmission Channels

We have shown that traditional social norms are the decisive force in the relationship between women’s marital power and their marital satisfaction. The following question is how traditional social norms bring about this situation. There will be some transmission channels through which traditional social norms exert their influence to cause a negative relationship between marital power and women’s marital satisfaction. Regarding this, we will continue by exploring possible important influencing channels.

The unique channel of women’s gender role attitudes is emphasized in the paper. Both years of education and income might play important roles in shaping women’s gender role attitudes and influencing their gender-equal behaviors. Numerous studies show that receiving more education can lead to more egalitarian gender role attitudes, especially among females (Brewster & Padavic, 2000; Deole & Zeydanli, 2021; Du et al., 2021). The liberalizing effect of education mainly operate through providing a gender-neutral curriculum (Cantoni et al., 2017) and changing the way people get access to new information (Jensen & Oster, 2009). Meanwhile, several studies revealed that the increased economic value of women, which improves women’s socioeconomic status, can foster more egalitarian gender role attitudes (Heath & Mushfiq, 2015; Jensen & Oster, 2009; Qian, 2008). For example, Xue (2018) found that a substantial, long-standing increase in relative female income eroded a highly resilient cultural belief in China: women are less capable than men. This is confirmed in Columns (1) and (2) in Table 6. Both women’s education and income are positively (/negatively) associated with their egalitarian (/traditional) gender role attitudes. In other words, those women with less education and income tend to support traditional gender beliefs that women play an auxiliary role in assisting their husbands. Once they cross the boundaries of social norms to become family decision-makers, their marital satisfaction will be affected negatively.

Additionally, strong traditional gender norms also might greatly shape women’s outlook on the world, life, and values, making them subconsciously accept conventional family ethics, such as “men being the masters of the family.” While influenced by their family members and peers at the stage of value formation, these women may be more likely to emphasize that women are unfit for political and economic affairs; instead, they should look after the household and children. This is confirmed in Column (3) in Table 6. The constraints of traditional gender norms in the community will strengthen women’s support for traditional gender role attitudes. Therefore, these women tend to comply with traditional social and cultural norms and are more willing to play a supportive role in assisting husbands and raising children (Turner & Salemink, 2015; Valutanu, 2012). Under such circumstances, once there is a deviation from the social norms, women’s marital satisfaction will be reduced.

Overall, we know that the force of Confucian family ethics exhibits greater influence than the socioeconomic transformation force in determining contemporary Chinese family lives. Once any deviation from the traditional gender role arrangement happens in the family, marital dissatisfaction will grow in women’s minds. While surrounded by traditional social norms, those women with less education and income tend to have traditional gender attitudes, so, they are unwilling to replace men as family decision-makers. Consequently, when we put women in a place against their will, their marital quality may suffer to some extent.

Propensity Score Matching

The empirical evidence above shows that women’s family decision-making power reduces their marital satisfaction. However, the result may be affected by the non-randomness of family decision-making power; that is, whether women have family decision-making power or not is not determined randomly. The difference in marital satisfaction between women who have family decision-making power and those who have none may be due to the characteristic variables that determine the women’s family decision-making power, rather than the behavior itself of those women who have family decision-making power.

There are some differences in many aspects between women who have family decision-making power and those who have none. This may cause estimation biases in the estimated coefficient on the independent variable due to self-selection effects. For example, women with certain demographic characteristics have a higher probability of holding family decision-making power but have a lower probability of being satisfied with their marriage. This would confound the negative effect of women’s family decision-making power on their marital satisfaction. Additionally, as mentioned in the literature, there is a large spillover effect within the family, especially between the spouses (Wang et al., 2019), whereby the behavior of a husband might change in response to his wife’s marital satisfaction. An unsatisfied woman might be granted more power to raise her satisfaction, and potentially keep her in the marriage. This will result in a self-selection bias of family decision-making power. To correct such a bias, this paper uses the propensity score matching (PSM) tool introduced by Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983) to find a control group with similar characteristics for the treatment group. In this way, we can obtain the treatment effect of women’s family decision-making power.

The PSM is a method that can effectively control self-selection bias based on observational data. In the framework of the PSM, we first need to obtain a propensity score (PS), which is the probability of an individual being assigned to the treatment group. In this paper, it is the probability that a woman has family decision-making power. To better obtain the estimated value of the probability, we generate a 0–1 dummy variable named \(Decision\_wife\). When the value of \(Decision\) is between 1 and 5, \(Decision\_wife\) is equal to 1; when its value is between -5 and 0, \(Decision\_wife\) is equal to 0. Thus, for \(Decision\_wife\), 1 means that women are in a dominant position in family decision-making process.

This paper selects the following matching covariates to predict the probability that a woman has family decision-making power: household registration (\(Urban\)), religious belief (\(Religion\)), age (\(Age\)), age difference (\(Age\_diff\), wife’s age–husband’s age), years of education (\(Education\)), years of education difference (\(Education\_diff\), wife’s education–husband’s education), annual income (\(Income\)), annual income difference (\(Income\_diff\), wife’s income–husband’s income), personality traits (\(Personality\)), personality traits difference (\(Personality\_diff\), wife’s personality traits–husband’s personality traits), interpersonal relationships (\(Relation\)), interpersonal relationship difference (\(Relation\_diff\), wife’s interpersonal relationship–husband’s interpersonal relationship), status of job (\(Employment\)), type of job (\(Jobtype\)), spouse’s status of job (\(S\_Employment\)), spouse’s physical appearance (\(S\_Appearance\)), and mutual trust between neighbors in the community (\(N\_trustc\)) and gender attitudes in the community (\(Rolec\)). Then, based on the calculated PS value, a counterfactual control group is constructed using matching methods to measure similarity. We can form an appropriately randomized experiment to infer the marital satisfaction effect of women having family decision-making power. To ensure the robustness of the treatment effect, we use three matching methods to estimate the marital satisfaction effect of women’s family decision-making power: nearest neighbor matching, radius matching and kernel matching.

Table 7 shows the estimation results obtained after matching with the PSM method. The average treatment effects on the treated group (ATT) have very similar values and significance in the PSM. Overall, in the three matching methods, women’s family decision-making power will affect their marriage satisfaction negatively. This provides strong evidence for the negative marital satisfaction effect of women having family decision-making power.

Table 8 shows that the pseudo R2 drops to about 0, and the likelihood ratio chi2 cannot reject the null hypothesis at the 1% significance level.Footnote 3 In all three matching methods, the mean bias and median bias after matching have been greatly reduced. Therefore, the PSM reliably eliminates the difference in observable characteristic variables between the treatment group and the control group. In summary, the data after matching by the PSM are balanced, and the negative effect on marital satisfaction of women having family decision-making power obtained from this is reliable.

Robustness Check

It is concerning that women’s marital satisfaction may be related to the status of “stay-at-home husbands.” Indeed, it may be not the power to make family decisions per se that reduces women’s marital satisfaction, but rather the need to work to feed the family and possibly involve a long-term career choice. To eliminate this confounding effect, we introduce working hours per week (\(Workhour\)) as a control variable in the model. Additionally, to reduce the dependence on a single independent variable, we use women’s family financial decision-making power (\(Finance\)) as a surrogate indicator for \(Decision\). It is assessed by “Who is the family financial decision-maker?” If the answer is “wife,” it is assigned 1, otherwise, 0. The ordinal probit model is again used here to estimate the regression results. Again, we use the question of “Who is the decision-maker of important family affairs” in the CFPS 2012, to generate a variable named \(Head\) as the proxy variable of \(Decision\) in the CFPS 2014. It is assigned 1 if the wife is the decision-maker of important family affairs; otherwise, it is 0. Columns (1), (2) and (3) of Table 9 show that family (financial) decision-making power still affects women’s marital satisfaction negatively, so, the robustness of our main results is further confirmed.

Extension: Men’s Marital Satisfaction

Contrasting women and men’s points of view could enrich the paper. So, besides women’s martial satisfaction, it would also be interesting to analyze men’s marital satisfaction, especially, the relationship between men’s family decision-making power and their martial satisfaction. To construct an econometric model, the dependent variable is men’s martial satisfaction (\(M\_satisfaction\_men\)), and the independent variable is men’s family decision-making power (\(Decision\_men\)). Their definitions are like the variables of women’s marital satisfaction (\(M\_satisfaction\)) and women’s family decision-making power (\(Decision\)) respectively. For \(M\_satisfaction\_men\), the larger the value, the more satisfied with his marriage a man is found to be; for \(Decision\_men\), the larger the value, the greater decision-making power in the family a man is found to have. While controlling for men’s demographic features, their spouses’ characteristics, family-level and community-level variables, Table 10 displays the results of OLS and ordinal probit regression. Different from that in Table 2, the coefficient of \(Decision\_men\) is insignificant at even 10% level. While setting aside the issue of significance, its coefficient is near zero. This indicates that there is no association of men’s martial satisfaction with their family decision-making power. In China, the patriarchal tradition dictates that men should be the masters of the household, and the women be generally housewives. So, in the majority of families, men dominate over family affairs, especially important family affairs, while women only handle trivial matters. The sense of men being the masters of the family has been deeply rooted in men’s minds, so, the contribution of men as decision makers to their martial satisfaction is not marginally significant. In this regard, men’s martial satisfaction is not dependent on their family decision-making power at all.

Discussion and Conclusion

Discussion

The extant literature shows that rising intra-household bargaining power improves women’s welfare including subjective well-being to a large extent (Liu, 2008; Luke & Munshi, 2011). However, our study reveals that women’s family decision-making power has a negative impact on their marital satisfaction. This unconventional finding is insightful for future policy on women’s development. Although a huge socioeconomic transition is happening in China, many women continue to embrace traditional gender norms; thus, they are unwilling to play the role originally assigned to men of being the primary decision makers in the family. So, at the current stage of development, a slowly-evolving gender identity still prevents Chinese women’s all-round empowerment.

Then, an important question follows. In a country where unprecedented socioeconomic changes are taking place, why do women continue to embrace such gender role norms as “men being the masters of the family.” From policymakers to ordinary people, everyone understands the importance of women’s empowerment and gender equality. However, a vast majority of people are reluctant to accept more egalitarian gender role arrangements. Even with societal transformation it remains difficult to shake the predominantly Confucian cultural base in contemporary China.

The reason for this paradoxical phenomenon could be attributed to the male-led and male-centric development model in China’s economic reform. In this model, improvements in family and community well-being benefit males dramatically, but females progress relatively slowly. China’s economic transition from the 1970s onward resulted in a variety of setbacks for females, including diminished employment opportunities for women, a lack of childcare and eldercare options, a widening gender wage gap and a resurgence of traditional stereotypes about women’s work (Wang & Klugman, 2020; Yang, 2020). With childcare for example, market reforms led to a decline in state-funded childcare support for women in the workforce, consequently, childcare responsibilities were shifted largely onto mothers and grandmothers. Combined with division of labor, it has put women in an extremely disadvantaged position in the labor market in recent years (Appleton et al., 2014). The abolishment of the decades-old one-child policy in 2015 severely impacted women’s job searches and career promotion because of work-childcare conflicts (He & Zhu, 2016). Female labor force participation (FLP) has declined to 62% in 2020 at its peak of 84% in the 1980s, the gender gap in LFP also has increased to 12%, given many female workers are pushed out of the labor force. Meanwhile, the idea that marrying well for women is better than financial independence is again prevalent, so, many women personally choose to serve their family members (Chen, 2018). As women have been placed in a disadvantaged position overall, they embrace the traditional gender norms of “men being the masters of the family.”

This is further confirmed in the heterogeneity analysis above. The negative marital satisfaction effect of women’s family decision-making power is found among those women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. For women with less education, employment opportunities are relatively scarce in a skill-based market economy. If employed, they are more likely to work long hours in low-wage jobs (Hughes & Maurer-Fazio, 2002; Kim, 2000). Female workers with less education may not receive adequate social pensions and often lack job security. The widening gender wage gap further reinforces women’s economic disadvantages (Zhao et al., 2019), thus, for these disadvantaged women, economic dependence on their husbands leads to stricter adherence to traditional gender norms. By contrast, the negative martial satisfaction effect is not found for socioeconomically advantaged women. This indicates that women can overcome their dependence on men for their well-being given adequate economic opportunities. Women’s advanced ideas and financial independence can eliminate the fetters of male dominance, and gain more intrahousehold bargaining power for their own well-being.

Accordingly, the government should continuously support women, especially women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds in both family and market domains, and most importantly, help them to build a more egalitarian gender identity. In the policy-making process, the gender dimension should be considered to empower women to attain more equal rights, roles, and responsibilities. It is imperative that developing nations promote the well-being of all its citizens by empowering women and fostering egalitarian gender norms. Related measures should be taken to ensure women’s fair access to economic and political opportunities, such as investing in women’s education and stringent enforcement of antidiscrimination laws. In particular, greater policy interventions providing targeted support for disadvantaged women are needed to create a more gender-equitable environment. As women and men are provided with equal opportunities, women’s well-being will be less constrained by gender-biased division.

Long term, the government should promote women-friendly policies in order to achieve a more equalitarian Chinese society. More immediately, the State must initiate and incentivize greater economic equality between men and women to avoid unnecessarily prolonging limiting gender role norms. We wonder whether the State wishes to prolong the traditional gender role norms or not. The answers can be inferred from current study, and it can be confirmed in contemporary China. The finding of a negative relationship between women’s marital satisfaction and their family decision-making power has important implications for contemporary Chinese families and society. The inference is that any factors enhancing women’s family decision-making power might unexpectedly undermine the marriage stability of the spouses. Consequently, this will negatively affect family development and social stability in the short run. The rising divorce rate in recent years, especially the increasing number of divorces initiated by women, may be a reflection of such situation as increasing bargaining power of women in China. Thus, short term, the State may be disincentivized from enhancing women’s bargaining power so as to maintain marriage and social stability. In the face of rising divorce rates and falling marriage and fertility rates, State-run media has been used to stigmatize educated and enterprising women. In recent years, “career-oriented women” have been criticized as “unresponsive toward household needs” in mass media. The prevailing narrative is that family harmony should not be sacrificed for women’s career pursuits. Instead, the place for a woman is in the home where her family members’ needs should be her top priority. The traditional family value system has revived and to some extent been further strengthened, where men are regarded as masters of the family (Yang, 2020). In addition, pro-government media also vilify women who remain unmarried in their late twenties and beyond as “leftover women.” This societal and familial pressure has caused many unmarried women to suffer shame, social embarrassment, and social anxiety (Magistad, 2013). The rebounded conservative and patriarchal views of marriage force women to pursue marriage and childbirth much earlier. Even for many educated women, the influence of public opinion prevents them from overcoming their dependence on men. Overall, with the governmental intervention, mass media, popular reality shows, advertisements, and other print media, have all served to exaggerate differences between men and women in terms of capabilities, division of labor and family roles. So, we expect the influence of traditional gender norms will continue to persist not until women overcome both visible and invisible pressures imposed by social norms.

The discussions above reveal that the policies initiated to achieve short-term objectives may run counter to the government’s long-term vision. So, we need to consider the sociocultural environment in designing policies to improve both women’s and overall social welfare. According to Akerlof and Kranton (2000), the degree of match between the social identity assigned to women and their acting behaviors is time variant. So, no general conclusions and policies on women’s marital satisfaction will fit for all countries. In the case of contemporary China, we cannot increase women’s martial satisfaction by discouraging them from strengthening intrahousehold bargaining power. It is because many women remain economically disadvantaged that they have to comply with the influential social norms of “men being the masters of the family.” Instead, more sustainable measures should aim at eliminating such a sex-biased social environment where women are not provided equal opportunities. In that situation, a gender egalitarian society will likely improve both women and men’s well-being in the long run.

It is interesting to note that we observed that men’s martial satisfaction was not at all dependent on their family decision-making power. This finding highlights a potential gap in the current literature, given that most of existing studies focus extensively on women’s well-being and perceived marriage quality. Without taking into account men’s martial satisfaction, it is presumptuous to give policy suggestions to improve the welfare and well-being of married partners. It remains to be determined why there is no association observed between men’s martial satisfaction and their family decision making power in contemporary China. Perhaps level of education, income, socioeconomic status, and cultural backgrounds might modify the lack of association. As was observed for women, there may be some heterogeneities of association between men’s martial satisfaction and their family decision-making power. Future research using a more recent dataset may be warranted to elucidate the driving factors behind this curious observation among the men in this study.

This paper has identified several interesting and insightful facts regarding family power relations and women’s marital satisfaction in contemporary China. Nevertheless, we note that there remain some limitations in the study. First, given the possible spillover effect within the family, the study not only controls women’s characteristics but also considers their spouses’ characteristics. However, some variables may have been omitted from Eq. (1). For example, other non-cognitive abilities, e.g., openness and extraversion are not included in “The Big Five.” Failure to control such factors that may influence intra-household bargaining power and women’s marital satisfaction leads to some estimation bias. Second, the finding is more likely to be a correlation than a causal relation. Accounting for data availability, we use the 2014 CFPS cross-sectional data to estimate the relationship. In a cross-sectional dataset, we are not able to fully remove the confounding factors as it would result in self-selection bias of women’s family decision-making power. Although the PSM method is applied, some self-selection effects based on unobservable factors remain to be handled. Given the importance of the topic, such a correlational study remains interesting and insightful for scholars and policymakers. In future, it is suggested for scholars to find a suitable exogenous shock as the instrument of family decision-making power, to better clarify the causal relation between family decision-making power and women’s marital satisfaction. Although there are great challenges and uncertainties, we expect that future research can take this opportunity to make the conclusion of this paper more robust and credible.

Conclusion

This paper uses the CFPS data to study the relationship between family decision making power and women’s marital satisfaction. After controlling for possible confounding variables, the current study found that overall, women’s marital satisfaction is negatively associated with their family decision-making power. A series of robustness checks, including the PSM method, obtained the conclusion consistent with benchmark regression. However, the heterogeneity analysis showed that the negative association between women’s family decision-making power and their marital satisfaction is found among those women with a lower educational level (income) and constrained by external cultural norms, but the association is not found among women from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. It is revealed that socioeconomically disadvantaged women tend to hold traditional gender norms, thus, when deviating from traditional norms to become family decision-makers, their martial satisfaction will be negatively affected.

Family decision-making power and women’s marital satisfaction.

Note The husband has more decision-making power if the value of \(Decision\) is less than zero; the wife and husband have equal decision-making power if the value of \(Decision\) is equal to zero; and the wife has more decision-making power if the value of \(Decision\) is greater than zero

Notes

The coefficient of correlation between the wife’s physical appearance and her husband’s physical appearance is 0.995. To avoid the multicollinearity problem in regression equation, we do not control female physical appearance, instead, controlling the husband’s physical appearance. This is consistent with positive assortative matching in marriage.

We do not display the correlation matrix due to its large number of rows and columns. It can be provided on request at any time if readers are interested in the matrix.

Additionally, the T-test results indicate that there is no systematic difference between the treatment group and control group for the covariates after the PSM. The results are available upon request.

References

Agarwal, B. (1997). “Bargaining” and gender relations: Within and beyond the household. Feminist Economics, 3(1), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/135457097338799

Akerlof, G. A., & Kranton, R. E. (2000). Economics and identity. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 715–753. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554881

Appleton, S., Song, L., & Xia, Q. (2014). Understanding urban wage inequality in China 1988–2008: Evidence from quantile analysis. World Development, 62, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.04.005

Beach, S. R. H., & Tesser, A. (1993). Decision making power and marital satisfaction: A self-evaluation maintenance perspective. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 12(4), 471–494. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1993.12.4.471

Bertrand, M., Kamenica, E., & Pan, J. (2015). Gender identity and relative income within households. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2), 571–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjv001

Bian, Y., Zhang, L., Yang, J., Guo, X., & Lei, M. (2015). Subjective wellbeing of Chinese people: A multifaceted view. Social Indicators Research, 121(1), 75–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24721388

Bredemeier, C., Gravert, J., & Juessen, F. (2021). Accounting for limited commitment between spouses when estimating labor-supply elasticities (IZA DP No. 14226). https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/14226/accounting-for-limited-commitment-between-spouses-when-estimating-labor-supply-elasticities

Brewster, K. L., & Padavic, I. (2000). Change in gender-ideology, 1977–1996: The contributions of intracohort change and population turnover. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(2), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00477.x

Bulanda, J. R. (2011). Gender, marital power, and marital quality in later life. Journal of Women & Aging, 23(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2011.540481

Cantoni, D., Chen, Y., Yang, D. Y., Yuchtman, N., & Zhang, Y. J. (2017). Curriculum and ideology. Journal of Political Economy, 125(2), 338–392. https://doi.org/10.1086/690951

Chen, M. (2018). Does marrying well count more than career? Personal achievement, marriage, and happiness of married women in urban China. Chinese Sociological Review, 50(3), 240–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2018.1435265

Cheng, L. (2008). The key to success: English language testing in China. Language Testing, 25(1), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532207083743

Chiappori, P.-A. (1988). Rational household labor supply. Econometrica, 56(1), 63–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/1911842

Chiappori, P.-A. (1992). Collective labor supply and welfare. Journal of Political Economy, 100(3), 437–467. https://doi.org/10.1086/261825

Chiappori, P.-A., Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., Molina, J. A., Theloudis, A., & Velilla, J. (2020). Intrahousehold commitment and intertemporal labor supply ( IZA DP No. 13545). https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13545/intrahousehold-commitment-and-intertemporal-labor-supply

Chiappori, P.-A., & Mazzocco, M. (2017). Static and intertemporal household decisions. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3), 985–1045. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20150715

Chiappori, P., & x, Andr, xe, & Oreffice, S. (2008). Birth control and female empowerment: An equilibrium analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 116(1), 113–140. https://doi.org/10.1086/529409

Deole, S. S., & Zeydanli, T. (2021). The causal impact of education on gender role attitudes: Evidence from European datasets (SSRN). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3791949

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Du, H., Xiao, Y., & Zhao, L. (2021). Education and gender role attitudes. Journal of Population Economics, 34(2), 475–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00793-3

Elam, A., & Terjesen, S. (2010). Gendered institutions and cross-national patterns of business creation for men and women. The European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2010.19

Elson, D. (1999). Labor markets as gendered institutions: Equality, efficiency and empowerment issues. World Development, 27(3), 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00147-8

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00235.x

Fitzpatrick, J., & Lafontaine, M.-F. (2017). Attachment, trust, and satisfaction in relationships: Investigating actor, partner, and mediating effects. Personal Relationships, 24(3), 640–662. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12203

Ge, S., & Yang, D. (2014). Changes in China's wage structure. Journal of the European Economic Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/jeea.12072

He, X., & Zhu, R. (2016). Fertility and female labour force participation: Causal evidence from urban China. The Manchester School, 84(5), 664–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/manc.12128

Heath, R., Mushfiq, M., & A. (2015). Manufacturing growth and the lives of Bangladeshi women. Journal of Development Economics, 115, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.01.006

Hughes, J., & Maurer-Fazio, M. (2002). Effects of marriage, education and occupation on the female / male wage gap in China. Pacific Economic Review, 7(1), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0106.00156

Jensen, R., & Oster, E. (2009). The power of TV: Cable television and women’s satus in India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1057–1094. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.3.1057

Johnson, M. D., & Anderson, J. R. (2013). The longitudinal association of marital confidence, time spent together, and marital satisfaction. Family Process, 52(2), 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01417.x

Kim, M. (2000). Women paid low wages: Who they are and where they work. Monthly Labor Review, 123, 26–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/41845234

Knowles, J. A. (2012). Why are married men working so much? An aggregate analysis of intra-household bargaining and labour supply. The Review of Economic Studies, 80(3), 1055–1085. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rds043

Lalonde, R. N., Hynie, M., Pannu, M., & Tatla, S. (2004). The role of culture in interpersonal relationships: Do second generation South Asian canadians want a traditional partner? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(5), 503–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022104268386

Leonhardt, N. D., Willoughby, B. J., Dyer, W. J., & Carroll, J. S. (2020). Longitudinal influence of shared marital power on marital quality and attachment security. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000566

Li, Y. (2000). Women’s movement and change of women’s status in China. Journal of International Women's Studies, 1(1), 30–40.

Liu, H. (2008). The impact of women’s power on child quality in rural China. China Economic Review, 19(1), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2007.01.002

Lowry, D., & Xie, Y. (2009). Socioeconomic status and health differentials in China (Population Studies Center Research Report No. 09–690). https://www.psc.isr.umich.edu/pubs/pdf/rr09-690.pdf

Luke, N., & Munshi, K. (2011). Women as agents of change: Female income and mobility in India. Journal of Development Economics, 94(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.01.002

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111

Mabsout, R., & van Staveren, I. (2010). Disentangling bargaining power from individual and household level to institutions: Evidence on women’s position in Ethiopia. World Development, 38(5), 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.11.011

Magistad, M. K. (2013). China's 'leftover women', unmarried at 27. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-21320560

Mak, G. C. L. (2013). Women, education and development in Asia: Cross-national perspectives. Routledge.

Mazzocco, M. (2007). Household intertemporal behaviour: A collective characterization and a test of commitment. The Review of Economic Studies, 74(3), 857–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-937X.2007.00447.x

Mazzocco, M., Ruiz, C., & Yamaguchi, S. (2014). Labor supply and household dynamics. American Economic Review, 104(5), 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.5.354

Pratten, N. (2013). Don’t pity China’s leftover women, they’ve got more going for them than you realise. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/dont-pity-chinas-leftover-women-theyve-got-moregoing-for-them-than-you-realise-8536872.html

Qian, N. (2008). Missing women and the price of tea in China: The effect of sex-specific earnings on sex imbalance. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3), 1251–1285. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.3.1251

Rogers, S. J., & DeBoer, D. D. (2001). Changes in wives' income: Effects on marital happiness, psychological well-being, and the risk of divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 458–472.

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

Rouhbakhsh, M., Kermansaravi, F., Shakiba, M., & Navidian, A. (2019). The effect of couples education on marital satisfaction in menopausal women. Journal of Women & Aging, 31(5), 432–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2018.1510244

Safilios-Rothschild, C. (1970). The sociology and social psychology of disability and rehabilitation. Random House.

Sarantakos, S. (2000). Marital power and quality of marriage. Australian Social Work, 53(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070008415556

Sayehmiri, K., Kareem, K. I., Abdi, K., Dalvand, S., & Gheshlagh, R. G. (2020). The relationship between personality traits and marital satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-0383-z

Thornton, A., & Lin, H.-S. (1994). Social change and the family in Taiwan. University of Chicago Press.

Treas, J., & Kim, J. (2016). Marital power. In C. L. Shehan (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Family Studies (pp. 1–15). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Turner, B. S., & Salemink, O. (2015). Routledge handbook of religions in Asia. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Valutanu. (2012). Confucius and feminism. Journal of Research in Gender Studies, 2(1), 132–140. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A327357308/AONE?u=anon~82498320&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=466802a2

Voena, A. (2015). Yours, mine, and ours: Do divorce laws affect the intertemporal behavior of married couples? American Economic Review, 105(8), 2295–2332. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20120234

Wang, L., & Klugman, J. (2020). How women have fared in the labour market with China’s rise as a global economic power. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 7(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.293

Wang, Q., Li, Z., & Feng, X. (2019). Does the happiness of contemporary women in China depend on their husbands’ achievements? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(4), 710–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09638-y

Wendorf, C. A., Lucas, T., Imamoğlu, E. O., Weisfeld, C. C., & Weisfeld, G. E. (2011). Marital satisfaction across three cultures: Does the number of children have an impact after accounting for other marital demographics? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(3), 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110362637

Whiteman, S. D., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2007). Longitudinal changes in marital relationships: The role of offspring’s pubertal development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(4), 1005–1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00427.x

Xie, Y. (2013). Gender and family in contemporary China (Population Studies Center Research Report No. 13–808). https://www.psc.isr.umich.edu/pubs/pdf/rr13-808.pdf

Xie, Y., & Hu, J. (2014). An introduction to the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Chinese Sociological Review, 47(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.2753/CSA2162-0555470101.2014.11082908

Xie, Y., & Lu, P. (2015). The sampling design of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Chinese Journal of Sociology, 1(4), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X15614535

Xue, M., Meng. (2018). High-value work and the rise of women: The cotton revolution and gender equality in China (MPRA Paper No. 91100). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2389218

Yang, J. h. (2020). Women in China moving forward: Progress, challenges and reflections. Social Inclusion, 8(2) , 23–35. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v8i2.2690

Yu, X., & Liu, S. (2021). Female labor force status and couple’s marital satisfaction: A Chinese analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 691460. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.691460

Zhao, X.-Z., Zhao, Y.-B., Chou, L.-C., & Leivang, B. H. (2019). Changes in gender wage differentials in China: A regression and decomposition based on the data of CHIPS1995–2013. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32(1), 3168–3188. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1660906

Acknowledgements

I thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their generous and insightful comments and suggestions to make the paper much improved.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest to this work, and they have no competing financial interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z. Family Decision Making Power and Women’s Marital Satisfaction. J Fam Econ Iss 44, 568–583 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09866-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09866-9