Abstract

The role of relative income has been greatly discussed in the studies of subjective well-being. However, it is rarely studied with couple’s relationship satisfaction. This study uses two waves of data from the China Family Panel Survey (N = 9,291 in the 2014 wave, and N = 6,844 in the 2018 wave) to examine the association between relative income status and couple’s marriage satisfaction. The multivariable logistic analyses were applied to test the hypotheses. Generally, we find that the relative income status compared with people out-household has an important role in explaining marital satisfaction for husband and wife. Such associations are both significant from family and individual perspectives, but heterogenous from a gender perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is apparent that marriage involves more than just an emotional connection, frequently, it also involves financial connections. The financial related issues often determine the quality and stability of marriage life (Archuleta, 2013; Britt-Lutter et al., 2019). According to Dew (2016) money related matters are often the most frequent source of conflict in a marriage. As financial problems are a reflection of the demands and expectations of a couple with low income, it is reasonable to expect low-income families tend to experience more financial stress, and lower marital and life satisfaction. However, many existing empirical evidences are not favorable to this assumption as studies show that the relationship between income and marital quality is weak and inconsistent (Hardie et al., 2014; Jackson et al., 2017; Maisel & Karney, 2012).

One possible reason for this incomprehensible result explained by Jackson et al. (2017) is because of the sample selection in different studies. The majority of studies that using large and representative samples are mostly couples with well-established marriages. Those who consider money as an important matter may already separate in the early years of marriage. Another possible reason that supported by many previous studies is marital quality may not solely depend on the absolute income but on the subjective feeling of the financial situation (Dew et al., 2012; Gudmunson et al., 2007) and financial management (Skogrand et al., 2011). When couples must constantly worry about money, frequently disagree on the way money should be spent, or have different opinions on how to manage their finances tend to experience more frequent conflict and lower marital happiness (Dew & Xiao, 2011; Tavakol et al., 2017).

For decades, studies on subjective well-being and income have provided strong evidence and suggest that individual income perception is also subject to the individual’s income compared with the income of others. The happiness studies taken a social comparison perspective in exploring the relationship between income and subjective well-being have found the “relative status” of the reference group has a significant effect on one’s happiness (Clark et al., 2008; Ferrer-i-Carbonell, 2005; Huang et al., 2016; Kifle, 2013). It means that one’s subjective feeling does not only depend on the absolute income but also the relative income compares to others. Given the empirical evidence on the weak relationship between income and marital quality, there is still no study that has taken relative income in comparison to others to evaluate couples’ relationship satisfaction. Therefore, the current study aims to fill up this gap by examining the relationship between the relative income and marital satisfaction in different sex married couples using nationally representative data from China.

This study aims to make two research contributions concerning previous works. First, compared with research on the direct relationship between income and marital satisfaction, this research extends the analysis of the income effect on marital quality by examining the relative income status in relation to marital satisfaction. It may contribute to the small empirical literature on establishing how the economic power of an individual or family associate with the satisfaction of family members. Secondly, previous studies such as Furdyna et al. (2008), Zhang et al. (2012), and Zhang and Li (2015) have done some work to establish the association between relative income and marital satisfaction within marriage. Whereas this study examines the relative income outside the family with the couple’s marital quality. It is important to note that the relative income of married couples is more complex than the relative income studied among individuals. For a married couple, there are family income and income of a husband or wife. Therefore, the relative income also can be seen from relative family income, relative income between husband and wife, and the husband’s or wife’s income relative to other individuals’ income. Husband/wife may not only evaluate their marriage based on their absolute family income as previous literature focused. The family’s relative income or the relative income between a couple, or the partner’s relative income compared to other people all may relate to marital quality.

Literature Review

Income and Marital Quality

Aspiration for a higher economic status seems to be part of human nature. People’s needs, wishes, and expectations are strongly shaped by economic power. Of the numerous studies focusing on the relationship between economic resources and marital quality, most assume economic resources are associated with couples’ happiness and satisfaction. They argue that abundant financial resources can provide couples with opportunities to engage in more activities that can reduce stress, and resolve conflicts (Dakin & Wampler, 2008). On the other hand, economic hardship will elevate psychological problems among the couples, leading to frequent conflict or lower relationship quality (Dean et al., 2007; Ross et al., 2021).

Despite income being the foundation of family economic resources, research that examines the direct relationship between family income and marital quality is relatively scarce. In general, evidence on the relationship between family income and marital quality in the last two decades tends to suggest that there is a weak and mixed relationship (Jackson et al., 2017; Karney & Bradbury, 2020). It is also consistent with the finding from the decade review on economic circumstances and family outcomes by White and Rogers (2000) in1990s. Among recent studies, researchers such as Hardie et al. (2014), Jackson et al. (2017), Maisel and Karney (2012), and Yunchao et al. (2020) studied samples from Germany, the United States, and Malaysia all find household income and marital satisfaction are unrelated. But Schramm and Harris (2011) used a sample of 295 married individuals from Utah, and Hardie and Lucas (2010) used two nationally representative surveys of young couples in the United States both found a positive relationship. In terms of the differences between husband and wife, studies like Chung et al. (2010) examined couples from Korea and Japan and find that wives’ satisfaction with their marriages is positively influenced by their family income while their husbands’ marital satisfaction is not for both countries. However, an investigation of the German sample by Hardie et al. (2014) found no significant relationship for either men or women.

Also need to be noted that most research that studies economic factors and marital quality commonly examines the subjective evaluation of economic resources and marital quality. These studies are supported by the family stress model (Conger et al., 1992) and Vulnerability–Stress–Adaptation (VSA) model (Karney & Bradbury, 1995) which perceived economic hardship increases emotional distress, increases conflictive marital interactions, and decreases positive marital interactions. The empirical evidence also favors these hypotheses and suggests that it is not the absolute income that matters in marriage, but the subjective situation of one’s finance (Barnett, 2008; Conger et al., 1999; Gershoff et al., 2007). Even if income is the foundation of family economic resources, the subjective feeling of income adequacy tends to matter more than the absolute value of income.

Relative Income and Marital Quality

Since Richard A. Easterlin’s seminal article (1974) sets out the “paradox” that self-reported happiness levels do not rise with substantial real income growth in Western countries over time, the relative income has been greatly studied with subjective well-being. The fundamental assumption under relative income with individual subjective well-being is the social comparison theory. The theory suggests that people do not evaluate their own lives in isolation, and they sometimes compare their income with that of others (Festinger, 1954). Many researchers in the last few decades have tested the social comparison hypothesis of happiness in different contexts. Numerous empirical evidence has constantly shown that having higher (lower) income than a reference group leads to higher (lower) subjective well-being for individuals, including job satisfaction and life satisfaction. (Clark et al., 2008; Gao & Smyth, 2010; Huang et al., 2016; Kifle, 2013; Knight et al., 2009; McBride, 2001; Oshio et al., 2011). However, among the existing literature that investigates the relationship between relative income and subjective well-being, little do we know about the relationship between the relative income and the marital quality of couples.

Most of the existing literature that researched the relative income and marital quality defined relative income as wife-to-husband income ratio or wife’s share of couple’s total income. Supported by different theoretical approaches from the dependence model to the gender identity model, research of this stream of studies examines how the wife’s relative income compare with her husband or within a family affects couples relationship satisfaction and subjective well-being. Such as Zhang et al. (2012) used the Chinese Urban Household Survey conducted in 2004 to study wives’ relative income and marital satisfaction among the urban Chinese population. Their finding shows that the relative income of wife has a more negative impact on a couple’s marital satisfaction, and this negative association is stronger for women than for men. Later Zhang and Li (2015) confirmed this result by examining 763 urban Chinese women suggesting that higher-earning wives tend to report lower marital happiness and higher marital instability. For couples in the United States, Bertrand et al. (2015) find that those couples with higher wife’s income compares with husband are less satisfied with their marriage. Hajdu and Hajdu (2018) examined nationally representative data from Hungary showing that the relationship between a woman’s relative income and the level of life satisfaction is unfavorable for both men and women.

In terms of the association between the wife’s income share within a family and her marital satisfaction and subjective well-being, mixed findings were revealed by studies. Such as Rodgers and DeBoer (2001) suggest that women’s absolute and relative income has a considerable positive impact on their marital happiness and well-being, whereas Furdyna et al. (2008) and Zhang and Li (2015) found negative relationship. But Chen and Hu (2021) using the 2014 China Family Panel Studies data found wife’s marital satisfaction has no significant relationship with wife’s earning more than husband. Different from the mixed findings on the wife’s marriage satisfaction and subjective well-being, more consistent findings show that wife’s relative income is negatively associated with husband’s marriage satisfaction and subjective well-being (Bertrand et al., 2015; Chen & Hu, 2021; Hajdu & Hajdu, 2018; Rodgers & DeBoer, 2001; Wu, 2021). Moreover, a nonlinear relationship also found by Syrda (2020) between wife’s relative income within a family and husband’s psychological distress is not only significantly related and also significantly U-shaped.

The Current Study

In summary, as reviewed above, previous literature has established the possible determinant of the wife’s relative income compared to the husband’s marital quality. However, no study has examined the association between relative income and marital quality from perspective of family and partner compared to other people. The current study is designed to explore these potential associations in several ways.

First, this study tests the relationship between family relative income status and marital satisfaction of husband and wife. With social comparison effect as the guiding theory, studies on relative income suggest that people tend to feel happier when their relative income status is higher compared to the reference group (Clark et al., 2008). At the time, the unitary household model (Becker, 1965) proposed that each household has one utility function and each household maximizes a common set of preferences where all income is pooled. Thus, when a couple earns more than others it may positively affect their subjective well-being and improve their feeling toward marriage. In contrast, lagging behind in earnings may reduce their subjective well-being and increase the possibility of heightening tensions and stressors. The tensions and stressors may further influence the couple’s ability to respond appropriately to issues surrounding their relationship then led to lower satisfaction with their marriage (Karney & Bradbury, 2020). This effect may pertain to both husband and wife as they share one utility of the household. We thus propose the following prediction.

Hypothesis 1

The higher relative family income status of one’s family compared to others, the higher husband’s and wife’s marriage satisfaction.

Second, this study tests whether the marital satisfaction of husband and wife is determined by their own relative income status. According to the dependence model, within a family, couples are financially interdependent. The income of a partner will not only relate to the well-being of the person but also their partner (Nock, 2001; Tisch, 2021). It is because the person with less income will depend on the partner with a higher income, which leads to the dependent partner feeling less satisfied, or the person with less income feeling anxious about a lower contribution. Therefore, the higher one’s relative income compared to others might improve their recognition within the family, and might have more influence on the resources of the household (Halleröd, 2005).

Nonetheless, the empirical studies that tested the association between partners’ income and their marital quality have shown mixed findings as reviewed in the previous section. Especially for samples from China, a wife earning more is negatively associated with her marital happiness (Chen & Hu, 2021; Zhang & Li, 2015). Although a wife earning more than other people is not like earning more than her husband, the higher relative income compared to other people may contribute to her confidence within the family and lead to better feelings toward her marriage. The same may apply for the husband. Thus, we propose the following prediction.

Hypothesis 2

The higher the relative income status of husband or wife compared to others, the higher the husband’s and wife’s marriage satisfaction.

Third, earning income has different meanings for each gender. According to the gender identity model, husbands are the “breadwinner” of the family. Husbands have the responsibility to provide financial contribution to the household and wives the responsibility of household chores (Trappe et al., 2015). The empirical evidence discussed above also strongly supports this assumption through data from different countries. It means that the traditional gender division norm— “men are breadwinners, women are homemakers” --- still exists among different cultures, which also include Chinese couples (Chen & Hu, 2021). Therefore, in terms of relative income compared to other people, when the husband’s income status is relatively lower, it might lead the wife to feel less satisfied with her husband’s financial contribution and then feel less satisfied in marriage. This is consistent with the norms of adult masculinity, where husbands have the responsibility to be the main breadwinner. In contrast, wives are not subject to the social expectations of main financial contributor to the family. Thus, we propose the following predictions.

Hypothesis 3

The higher relative income status of the husband compares to others, the higher the wife’s marriage satisfaction.

Hypothesis 4

There is no significant correlation between the relative income status of wife compared to others and husband’s marriage satisfaction.

Data, Measurements and Empirical Methodology

Data

The data for this study come from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) which is a nationally representative and longitudinal survey dataFootnote 1. It was conducted by the Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University every two years. The first wave of CFPS was initiated in 2010 and covers 25 provincial regions across the country. Beginning with 2016 wave, samples from all 31 provincial regions were included. The latest wave available online is the CFPS 2020. For all waves, the observations are on an individual basis but nested within a particular household. Symmetrical information for a gene and core members of the family was collected in each wave.

For this study, we restrict our sample to CFPS 2014 and CFPS 2018 because only these two waves provided data on questions that related to marriage satisfaction. The 2014 wave contains 37,147 individuals in 13,946 households. The 2018 wave contains 32,669 individuals in 14,241 households. Based on samples in these two waves, we constructed a dataset where the level of observation is the couple. For each married individual, information on their spouse has been matched. Respondents for single households, separated, or where only one person responded within a family were dropped. After matching and cleaning the data, a total of 16,135 married couples with 9,291 from 2014 to 6,844 from 2018 were included for analysis. These couples are restricted to different-sex married couples living in the same household. The questionnaire was answered by both partners.

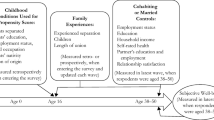

Measurements

Marriage satisfaction. The dependent variable in this study is marriage satisfaction that is measured by the question “How satisfied are you with your current married life?“. The responses range from 1 (being very dissatisfied) to 5 (being very satisfied). As marital satisfaction typically skewed high, we created a new dichotomous variable in which satisfied (4) and very satisfied (5) were combined and coded as 1. Respondents reporting 3 and below were combined and coded as 0. The same practice can be found in other studies on marital quality (Britt & Huston, 2012; Furdyna et al., 2008; Kaufman & Taniguchi, 2006).

Relative income. Who one compares to whom is a core issue for studies exploring the relationship between relative income and subjective well-being (Van Praag, 2011). Generally, the objective approximation method and subjective self-assessment method have been applied by most research in measuring relative income. Despite its accuracy in calculation, the major critique of the objective approximation method is its approximate selection of reference groups (Van Praag, 2011). In contrast, a subjective self-assessment can solve this challenge by capturing the respondent’s psychological process. Therefore, given the CFPS survey included a question on subjective feeling about an individual’s income level compared to people in their living area, this study used the subjective measure of relative income for all couples in the sample.

The main independent variable in this study is the perceived relative income of couples. There are two types of relative income in a family used in this study. One is the relative income of the individual compared to others; the other is the relative family income. In terms of individual’s relative income, the CFPS survey provide a question on “What is your relative income level in your local area?” The response ranges from 1 to 5 representing relative income from very low (1) to very high (5) where a higher score represents a higher income status of the person.

For the relative family income, however, the CFPS survey does not provide questions on the subjective measure. Thus, we defined the couple’s relative family income by combining the couple’s relative income status measured above. For each couple, the relative family income was computed by summing the relative income score of the husband and wife. The score ranges from 2 to 10 with a higher score representing a higher income status of the family.

Demographic and socioeconomic variables. Consistent with existing literature, commonly used demographic and socioeconomic variables were included as control variables. The variables included age (age categories: below 25 years old, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, 56–65, and 65 and above), education (below primary education, primary, lower secondary, upper secondary, and college and above), family income (natural log transformed), employment (employed, not employed), self-rated health status (extremely healthy, very healthy, somehow healthy, neutral, not healthy), family size, and urban/rural.

Empirical Methodology

This study applied multivariable logistic analyses to test the above hypotheses. The general specification of the regression model is below:

Where \({MS}_{i}\) represents marriage satisfaction of husband or wife i at time t.\({I}_{it}\) is the vector of income variables for a couple, or husband, or wife i at time t.\({RI}_{it}\) is the vector of relative income variables for a couple, or husband, or wife i at time t.\({X}_{i}\) include the demographic and socioeconomic controls that are education level, employment status, health status, education level of the spouse, employment status of the spouse, health status of the spouse, urban/rural, and family size. Given four years gap of the sample data and large income gap between provinces in China, year fixed effects (\({Year}_{i}\)) and province fixed effects (\({Provin}_{i}\)) are all included in the model. μit is the error term.

When panel data are available, time-invariant unobserved individual characteristics can be incorporated in regressions and could potentially be associated with observables in the model (1). However, as the income level of an individual or a family may vary within our sample period, the main independent factors of interest (relative income status) did not change significantly. Therefore, the coefficients in (1) are estimated by logistic regression. Furthermore, since data from changes within an individual were only considered in the fixed effects regression model, the fixed effect logistic regression estimation cannot be applied to our sample due to many variables being time-invariant. Therefore, we also conducted random effect logistic regression to confirm model (1). In our random effect logistic regression, the unobservable characteristics that were constant across time but different for each province are accounted for.

Results

Descriptive Findings

The descriptive statistics for all the variables used in the empirical analysis are presented in Table 1a and 1b. The mean values were calculated based on all samples for husbands and wives respectively in both years. The t-test was conducted for some of the variables to compare the differences between husbands and wives. From Table 1a we find that there is a significant difference between husbands and wives in their marriage satisfaction in the case of China. That 91% of husbands and 83.6% of wives reported being satisfied with their marriage shows that the responses on marriage satisfaction tended to be highly skewed. Concerning relative income status, men reported higher relative income status than women on average. Even though the difference was relatively small, it was still significantly different between husbands and wives. The sample also shows that husbands tended to be older than their wives by about 2 years on average,as well as higher educated, and tended to be employed. However, wives tended to report better health status compared to their husbands. For family variables in Table 1b, there were about 46% of couples living in a rural area, and 4.37 people per household. The mean value for relative family income status was 5.48. It was slightly lower than the median of the relative family income scale.

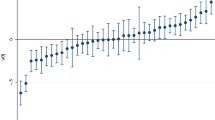

Relative Family Income and Marriage Satisfaction

Table 2 presents the results for the first hypothesis that expects the relative family income status to be positively associated with husband’s and wife’s marriage satisfaction. Columns (1) and (2) present the results for the husband, and columns (3) and (4) present the results for the wife. The results from four models in columns 1–4 showed that regardless of husband or wife, their own marriage satisfaction is significantly related to their relative family income status. Both random effect logistic regression and logistic regression are consistent in the association between relative family income status and marriage satisfaction for husbands and wives. By comparing the coefficient of relative family income between husband and wife, we can see the tendency that wives’ marriage satisfaction is higher than husbands. Regarding family income, our results are consistent with some of the previous studies and reveal that among Chinese couples their family income tends not to determine their marital satisfaction. Therefore, like studies on the relationship between income and life satisfaction, evidence from Chinese couples in this study suggests that it is not the absolute family income that matters in couple’s marriage satisfaction, but the family’s relative income status.

Beside the main independent variables, this study included respondent’s and spouse’s socioeconomic and demographic variables as controls. Interestingly, the results showed that spouse’s education level matters in husband’s and wife’s marriage satisfaction rather than their own. The higher the spouse’s education level, the higher the level of marriage satisfaction reported by both husband and wife. The higher coefficient of husbands than wives means that wives education level is stronger in determining husbands’ satisfaction than husbands’ education level on wives. The results also showed that health status for husband and wife both negatively affected their own marriage satisfaction and their partner. Older couples tended to be more satisfied with their marriage compared to younger couples. Moreover, wives’ employment status was negatively related with husbands’ marriage satisfaction, but husbands’ employment status did not show any significant relationship.

Relative Income and Marriage Satisfaction

Table 3 presents the results of the second hypothesis that examined the association between the relative income status of husbands and wives marriage satisfaction compared to others. Same as above, columns (1) and (2) present the results for husbands and columns (3) and (4) present the results for wives. The results are supportive of the proposed hypothesis in that the relative income status of husband and wife were both significantly and positively associated with their marriage satisfaction. Considering the association between husband and wife, the higher coefficient of the wives’ relative income indicates that it had a stronger correlation for wives than for husbands. However, regarding income, the result showed that only husbands’ income determines his marriage satisfaction, as wives’ income did not show any significant relationship with her appraisal of marriage satisfaction. A similar result was also found by Qian and Qian (2015) on urban Chinese people finding that a man’s income contribution had a greater beneficial impact on his life satisfaction than a woman’s contribution to her life satisfaction.

In terms of third hypothesis, the results found in Table 4 show that husbands’ relative income is significantly related to wives’ marriage satisfaction given both partner’s socioeconomic and demographic characteristics are controlled. This result is supportive of the hypothesis in that the higher the relative income status of the husband compared to others, the higher his wife’s marital satisfaction. Similar to Wu’s (2021) finding that the husband earning more than his wife was positively related to the wife’s life satisfaction, in our case, the husband’s relative income status compared with others also matters for his wife’s marriage satisfaction. Interestingly, unlike the husband’s relative income status, husbands’ absolute income was negatively associated with wives marriage satisfaction. This indicates that Chinese wives who had higher-income husbands tended to be less satisfied with their marriage.

In contrast, both models in columns (1) and (2) show that wives’ relative income status was nonsignificantly related to their husbands’ level of marriage satisfaction. This is also supportive of the fourth hypothesis. Moreover, wives’ absolute income also did not show any significant relationship with their husbands’ marriage satisfaction. However, these results are not consistent with previous studies that found that wives earning more than their husbands had a negative association with husbands’ marriage satisfaction (Bertrand et al., 2015; Chen & Hu, 2021). Our findings suggest that when wives income status is compared not with their husband but outside the family, their income status does not significantly impact husbands’ feelings toward marriage. This indicates that there are gender differences in terms of spouses’ relative income status and their feeling toward their marriage.

Supplementary Analysis

To check the robustness of the findings, we only selected data for dual-earner families since some husbands/wives from our original sample had no income. Their relative income status may not be consistent with their true income level compared to others. After applying the same logistic regression as above and presenting the results in Table 5, we found that the majority of the results were consistent with the previous analyses of the original sample. Relative family income and husbands’ relative income status wrre both positively and significantly associated with husbands’ marriage satisfaction. For wives marriage satisfaction, the relative family income status, wives relative income status, and husbands’ income status all showed a positive and significant relationship. The only differences with the previous analyses were husbands’ income did not show any significant relationship with wives’ marriage satisfaction as presented in Table 4. This may be because when wives also earn some level of income, they are not solely dependent on their husbands. This may account for the previous negative association between wives’ marital satisfaction and their husbands’ income level.

Conclusion and Discussion

This study expands on previous literature on the impact of income on marital quality by investigating relative income status in relation with marital satisfaction using data from CFPS 2014 and 2018. In general, this study confirmed the hypotheses about the relationships between the relative income status of family and spouse compared with people outside the household and the marital satisfaction of husband and wife. At the family level, however, the direct relationship between family income and marital satisfaction is not significant in contrast to the majority of previous literature: the relative income status of a family tends to positively determine the marital satisfaction of husbands and wives in China. In terms of individual perspectives, the hypothesis of one’s relative income status may be positively associated with one’s marital satisfaction is also supported by our results. As one of the contributions of this study that investigate the relative income status of husband and wife, our findings show that the higher one’s relative income compared to others might improve one’s marital satisfaction. This is confirmed for both husband and wife as higher relative income status might improve their individual recognition within the family. Moreover, our findings also confirmed that the gender norm may also exist from the perspective of relative income status among Chinese couples. The higher relative income status of the husband compared to others is associated with the higher marriage satisfaction of wives, but no significant correlation showed between the relative income status of wives’ and husbands’ marital satisfaction.

Our results shed light on relative income status that could determine the marital satisfaction of husbands and wives from the family and spouse perspective. Based on the findings, this study suggests that relative income status is not only important to one’s subjective well-being as many economic and social studies revealed, but also to couples’ marital quality. People do not evaluate their own lives in isolation, they sometimes compare their income with that of others (Clark et al., 2008). In the case of married couple, we suggest that married couples in general may compare their family income with that of others and may also compare their spouse’s income with others. This is more apparent on the husband’s relative income status. Beside the spousal relative income, the relative income of spouses compared to people outside the household also need to be considered as it may determine the quality and stability of married life. Given the trend of an increasing proportion of women participating in the labor market in many societies, more wives are earning some level of income and may also earn more than their partners (Cooke, 2010). The existence of the “breadwinner–homemaker” social norm in these societies may understate wives’ income contribution in improving couples’ relationship quality

Lastly, our study has some limitations that can be considered while framing future research studies. Unlike many studies that investigate relative income using objective measures, perceived relative income was used in this study. Although the subjective measure can capture the respondent’s psychological process and it is an ideal measurement of relative income status as suggested by some studies (Wu, 2021), it does not rule out the issue of “compared to whom” in husbands’ view of wives contribution, or wives’ view of their husband. Perceived relative income is a self-evaluated relative status. The reference group that is compared to the wife in the view of the husband may not be the same as the wife’s view. The same may may be said of the inverse. Therefore, further investigation is needed regarding these challenges. Moreover, given only two waves of the sample have been examined in this study due to the availability of data, longitudinal studies with more waves are needed.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data required to reproduce the findings of this study are available to download from http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/download after registration. The processed data required to reproduce the findings of this study are available upon request.

Notes

The CFPS data can be obtained from Peking University Open Research Data webpage through registration. https://opendata.pku.edu.cn/.

References

Archuleta, K. L. (2013). Couples, money, and expectations: Negotiating Financial Management Roles to increase relationship satisfaction. Marriage & Family Review, 49, 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2013.766296.

Barnett, M. A. (2008). Economic disadvantage in complex family systems: Expansion of family stress models. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11(3), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-008-0034-z.

Becker, G. (1965). A theory of the allocation of Time. The Economic Journal, 75(299), 493–517.

Bertrand, M., Kamenica, E., & Pan, J. (2015). Gender identity and relative income within households. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2), 571–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjv001.

Britt, S. L., & Huston, S. J. (2012). The role of money arguments in marriage. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33(4), 464–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9304-5.

Britt-Lutter, S., Haselwood, C., & Koochel, E. (2019). Love and money: Reducing stress and improving couple happiness. Marriage and Family Review, 55(4), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2018.1469568.

Chen, Y., & Hu, D. (2021). Gender norms and marriage satisfaction: Evidence from China. China Economic Review, 68(April), 101627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101627.

Chung, K., Kamo, Y., & Yi, J. (2010). What makes Husband and Wife satisfied with their marriages: A comparative analysis of Korea and Japan *. Korea Journal of Population Studies, 33(17330119), 133–160.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., Shields, M. A., & Clark, E. (2008). Relative income, happiness, utility: An for the Explanation Easterlin and other Puzzles Paradox. American Economic Review, 46(1), 95–144.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., Development, C., Jun, N., Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F., Simons, R. L., & Whitbeck, L. B. (1992). A family process model of Economic Hardship and Adjustment of Early adolescent boys. Child Development, 63(3), 526–541.

Conger, R. D., Rueter, M. A., & Elder, G. H. Jr. (1999). Couple resilience to economic pressure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(1), 54–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.54.

Cooke, F. L. (2010). Women’s participation in employment in Asia: A comparative analysis of China, India, Japan and South Korea. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(12), 2249–2270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2010.509627.

Dakin, J., & Wampler, R. (2008). Money doesn’t buy happiness, but it helps: Marital satisfaction, psychological distress, and demographic differences between low- and middle-income clinic couples. American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(4), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180701647512.

Dean, L. R., Carroll, J. S., & Yang, C. (2007). Materialism, perceived financial problems, and marital satisfaction. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 35(3), 260–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X06296625.

Dew, J. P. (2016). Revisiting Financial Issues and Marriage. In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research (pp. 281–290). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1

Dew, J. P., & Xiao, J. J. (2011). The Financial Management Behavior Scale: Development and validation. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 22(1), 43–59.

Dew, J., Britt, S., & Huston, S. (2012). Examining the relationship between Financial Issues and Divorce. Family Relations, 61(4), 615–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00715.x.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2005). Income and well-being: An empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. Journal of Public Economics, 89(5–6), 997–1019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.003.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202.

Furdyna, H. E., Tucker, M. B., & James, A. D. (2008). Relative spousal earnings and marital happiness among african american and White Women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(May), 332–344.

Gao, W., & Smyth, R. (2010). Job satisfaction and relative income in economic transition: Status or signal?. The case of urban China. China Economic Review, 21(3), 442–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2010.04.002.

Gershoff, E. T., Aber, J. L., Raver, C. C., & Lennon, M. C. (2007). Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Development, 78(1), 70–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00986.x.

Gudmunson, C. G., Beutler, I. F., Israelsen, C. L., McCoy, J. K., & Hill, E. J. (2007). Linking financial strain to marital instability: Examining the roles of emotional distress and marital interaction. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28(3), 357–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-007-9074-7.

Hajdu, G., & Hajdu, T. (2018). Intra-couple income distribution and subjective Well-Being: The moderating effect of gender norms. European Sociological Review, 34(2), 138–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy006.

Halleröd, B. (2005). Sharing of housework and money among swedish couples: Do they behave rationally? European Sociological Review, 21(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci017.

Hardie, J. H., & Lucas, A. (2010). Economic factors and relationship quality among young couples: Comparing cohabitation and marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1141–1154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00755.x.

Hardie, J. H., Geist, C., & Lucas, A. (2014). His and hers: Economic factors and relationship quality in Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(4), 728–743. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12129.

Huang, J., Wu, S., & Deng, S. (2016). Relative income, relative assets, and happiness in Urban China. Social Indicators Research, 126(3), 971–985. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0936-3.

Jackson, G. L., Krull, J. L., Bradbury, T. N., & Karney, B. R. (2017). Household Income and Trajectories of Marital satisfaction in early marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(3), 690–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12394.

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3.

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (2020). Research on marital satisfaction and Stability in the 2010s: Challenging Conventional Wisdom. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12635.

Kaufman, G., & Taniguchi, H. (2006). Gender and marital happiness in later life. Journal of Family Issues, 27(6), 735–757. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05285293.

Kifle, T. (2013). Relative income and job satisfaction: Evidence from Australia. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 8(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-012-9186-6.

Knight, J., Song, L., & Gunatilaka, R. (2009). Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China. China Economic Review, 20(4), 635–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2008.09.003.

Maisel, N. C., & Karney, B. R. (2012). Socioeconomic status moderates associations among stressful events, mental health, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(4), 654–660. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028901.

McBride, M. (2001). Relative-income effects on subjective well-being in the cross-section. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 45(3), 251–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(01)00145-7.

Nock, S. L. (2001). The Marriages of equally dependent spouses. Journal of Family Issues, 22(6), 755–775.

Oshio, T., Nozaki, K., & Kobayashi, M. (2011). Relative income and happiness in Asia: Evidence from nationwide surveys in China, Japan, and Korea. Social Indicators Research, 104(3), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9754-9.

Qian, Y., & Qian, Z. (2015). Work, Family, and Gendered Happiness among Married People in Urban China. Social Indicators Research, 121(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0623-9.

Rodgers, S. J., & DeBoer, D. D. (2001). Changes in wives ’ income: Effects on Marital Changes and the happiness, psychological risk of divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 458–472.

Ross, D. B., Gale, J., Wickrama, K., Goetz, J., Vowels, M. J., & Tang, Y. (2021). Couple perceptions as Mediators between Family Economic strain and Marital Quality: Evidence from Longitudinal Dyadic Data. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 32(1), 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1891/JFCP-18-00065.

Schramm, D. G., & Harris, V. W. (2011). Marital quality and income: An examination of the influence of Government Assistance. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(3), 437–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9212-5.

Skogrand, L., Johnson, A. C., Horrocks, A. M., & DeFrain, J. (2011). Financial Management Practices of couples with great marriages. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9195-2.

Syrda, J. (2020). Spousal relative income and male psychological distress. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(6), 976–992. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219883611.

Tavakol, Z., Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A., Behboodi Moghadam, Z., Salehiniya, H., & Rezaei, E. (2017). A review of the factors Associated with marital satisfaction. Galen Medical Journal, 6(3), 197–207. https://doi.org/10.22086/gmj.v6i3.641.

Tisch, D. (2021). My gain or your loss? Changes in within-couple relative wealth and partners’ life satisfaction. European Sociological Review, 37(2), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa052.

Trappe, H., Pollmann-schult, M., & Schmitt, C. (2015). The rise and decline of the male breadwinner model: Institutional underpinnings and future expectations. European Sociological Review, 31(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv015.

Van Praag, B. (2011). Well-being inequality and reference groups: An agenda for new research. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-010-9127-2.

White, L., & Rogers, S. J. (2000). Economic Circumstances and Family Outcomes: A review of the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1035–1051.

Wu, H. F. (2021). Relative income Status within Marriage and Subjective Well-Being in China: Evidence from Observational and Quasi-Experimental Data. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(1), 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00237-5.

Yunchao, C., Yusof, S. A., Amin, R. B. M., & Arshad, M. N. M. (2020). The Association between Household debt and marriage satisfaction in the Context of Urban Household in Klang Valley Malaysia. Journal of Emerging Economies and Islamic Research, 8(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.24191/jeeir.v8i1.7122.

Zhang, H., & Li, T. (2015). The role of willingness to sacrifice on the relationship between urban chinese wives ’ relative income and Marital Quality. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 41(3), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2014.889057.

Zhang, H., Tsang, S. K. M., Chi, P., Cheung, Y. T., Zhang, X., & Yip, P. S. F. (2012). Wives’ relative income and marital satisfaction among the Urban Chinese Population: Exploring some moderating Effects. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 43(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.49.1.5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest Statement

All authors of this study declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Y., Li, Q. The Role of Relative Income in Determining Marital Satisfaction for Husband and Wife in China. J Fam Econ Iss 45, 45–55 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-023-09904-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-023-09904-0