Abstract

Research has considered the role of social learning in substance use and determined that social influences are powerful determinants of substance initiation. However, the relationships between peer, sibling, and parent behaviors and e-cigarette initiation among early adolescents, and rural youth in particular, have yet to be examined. The present study investigated how peer delinquency, sibling substance use, and parental approval contribute to risk of e-cigarette initiation across middle school while also examining these associations with alcohol use initiation. Adolescents (N = 663) self-reported perceptions of peer delinquency, sibling substance use, parental approval about substance use, and their own e-cigarette and alcohol use. Multilevel survival analyses were conducted to model the risk of initiation and predictors of this risk. Results indicate that the risk of e-cigarette initiation increased by 75% annually as youths progressed through middle school. All social factors were significant predictors of e-cigarette initiation, while perceived peer delinquency and parental approval predicted alcohol initiation. Results emphasize the importance of early intervention for preventing e-cigarette initiation and the influence of peers and parents on alcohol initiation and the influence of peers, siblings, and parents on e-cigarette use.

Highlights

-

This study contributes to our understanding of the risk of e-cigarette and alcohol initiation across middle school in a sample of rural youth.

-

Results suggest that the risk of e-cigarette initiation increased by 75% annually across middle school, but the risk for alcohol initiation remained higher and stable.

-

Findings identified peer delinquency and parental approval as risks for both e-cigarette and alcohol initiation.

-

Sibling substance use was significantly associated with e-cigarette but not alcohol initiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For many, adolescence is a time of risk-taking and experimentation, and middle school represents a peak period for substance initiation (D’Amico & McCarthy, 2006). However, little research to date has examined e-cigarette initiation in this age group. Furthermore, research on risk and protective factors for e-cigarette use among rural adolescents is sparse, though research has identified differences in prevalence rates among urban and rural high school-aged youth (Noland et al., 2017). Increasing rates of adolescent e-cigarette use (Johnston et al., 2020; Miech et al., 2021) coupled with e-cigarettes’ developmental consequences (McCabe et al., 2018), necessitate further consideration of e-cigarette initiation, particularly among rural youth. The current study addresses these gaps in the literature by examining the timing of risk for e-cigarette initiation and considers multiple sources of socialization (i.e., peers, siblings, and parents) for e-cigarette initiation among rural middle school students. Additionally, to further inform our understanding of the timing and risk factors for e-cigarette initiation, we present e-cigarette findings alongside those of alcohol, which has more research available on the importance of social influences (e.g., Barnow et al., 2004; Donovan & Molina, 2011; Fagan & Najman, 2005; Hoeben et al., 2021; Widdowson et al., 2020).

Early Substance Initiation and Subsequent Consequences

The current study focuses on e-cigarette initiation among early adolescents, which is a sensitive period for engaging in substance use (D’Amico & McCarthy, 2006). Indeed, prior research suggests that e-cigarette use is prevalent among middle school-age youth (Fite et al., 2020). National data suggest a 9% increase in nicotine vaping among 8th grade students from 2017 to 2019, with 35% of youth initiating e-cigarette use by 12th grade (Johnston et al., 2020). Even with its relative novelty, e-cigarette use has been linked with increased risk for alcohol, tobacco, and drug use (Chang & Seo, 2020; McCabe et al., 2018). E-cigarette use is also associated with the use of multiple other types of combustible tobacco products, which give rise to their own developmental risks (e.g., school drop-out; Johnston et al., 2014). Finally, e-cigarette use is associated with increased risky behaviors related to sex, driving, and violence (Chang & Seo, 2020). Early substance initiation more broadly has been consistently linked with an increased risk for substance dependence across substances (i.e., alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana) across late adolescence and adulthood (Dawson et al., 2008; Van Ryzin & Dishion, 2014). Furthermore, prior research suggests that prevention efforts in middle school may be most effective (Marsiglia et al., 2011). There are differences in prevalence rates of substance use between rural and urban youth with rural youth indicating greater alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and drug use (Lambert et al., 2008; Rhew et al., 2011). Limited information about rural versus urban e-cigarette use suggests differences, though some findings indicate higher rates of use among rural youth (Dai et al., 2021), while others indicate higher rates of use among urban youth (Noland et al., 2017). While there are some data suggesting risk for initiation of e-cigarette increases throughout high school (Ortega et al., 2021), the current study advances the literature by examining risk for early e-cigarette initiation from 6th to 8th grade in a rural sample. We also examined social factors (i.e., peer delinquency, sibling e-cigarette use, and parental approval about e-cigarettes) that likely contribute to adolescents’ risk for early initiation of e-cigarettes to inform targets of prevention and intervention.

Socialization in Substance Use

Social learning theory holds that behaviors (e.g., substance use) are shaped by individuals’ social environments (Bandura, 1977), which includes family and friends. However, individuals’ physical environments also shape behaviors and interact with their social environments to influence learning (Pea, 1993). For example, parents, siblings, and peer influences on substance use may depend on access and availability of substances as well as amount of time one is able to spend with each of these influences, which likely varies in rural settings. Thus, research ought to examine multiple social influences of substance use and to consider the environmental context (e.g., rural settings) when examining such associations.

For all youth, caregivers provide important opportunities for social learning. Adolescents’ perceptions of parental substance use influence their own behaviors (Li et al., 2002). Research suggests that the influence of parental use peaks in middle school years, while peer and older sibling use is most concordant with individual use in high school (Salvy et al., 2014). Though perceptions of parental substance use clearly shape adolescents’ behaviors, parental attitudes about substance use have also been shown to predict youth substance use (Fite et al., 2018; Sale et al., 2003). Parental attitudes about substance use perpetuate norms that inform adolescents’ attitudes about substance use (Wilson & Donnermeyer, 2006). Additionally, having a family environment that is more alcohol-positive (e.g., greater parental alcohol use, perceived approval of alcohol use) contributes to early initiation (Donovan & Molina, 2011). Parental approval may also inform parents’ communication about substance use, which in turn influences youth behaviors (Miller-Day & Dodd, 2004; Miller-Day & Kam, 2010). To date, only one study has considered the influence of youth’s perceptions of parental attitudes on e-cigarette use specifically. Fite et al. (2018) found that high schoolers reported more favorable parental attitudes for e-cigarette use relative to tobacco use, and more favorable parental attitudes were associated with greater likelihood of having used e-cigarettes. Among youth residing in rural settings, parental influences (e.g., closeness, monitoring) may be especially protective for rural compared with urban youth (De Haan et al., 2010), who may have greater access to peers (Brody & Murry, 2001) and may be more susceptible to non-family peer influences (Wilson & Donnermeyer, 2006). Thus, more research examining the influence of parental approval on e-cigarette use among rural youth while also considering other socialization factors is warranted.

Siblings are also important agents of social learning who represent a unique source of socialization since they are family members like parents but typically close in age like peers (Stormshak et al., 2004). Siblings share contextual factors (e.g., home environment, genetics, or parenting behaviors), but siblings also engage in mutual processes of social deidentification and social learning (Whiteman et al., 2009). Youth spend most of their childhood with their siblings, and siblings are a source of social support and companionship like peers, though siblings often spend more time together, have continuous lifelong relationships, and are in the same family system (Stormshak et al., 2004). For these reasons, siblings may model and reinforce substance use behaviors, accounting for variability in substance use that is otherwise unexplained by peers or parents. Indeed, perceived sibling use is associated with adolescent’s substance use behaviors (Fagan & Najman, 2005; Fite et al., 2018), and older siblings’ use is associated with younger siblings’ substance use intentions (Maiya et al., 2023) and behaviors (Whiteman et al., 2013). Sibling attitudes alone are sufficient to impact youths’ substance use behaviors (Pomery et al., 2005). One twin study asserts that correspondence of substance use between siblings is more likely due to shared environmental factors (e.g., mutual friends) than genetic susceptibility (Rende et al., 2006). However, shared environmental factors do not completely account for associations in sibling use behaviors. One study found that mutual modeling and younger siblings’ admiration of older siblings, in addition to shared friends, contributed to youth risk of substance use (Whiteman et al., 2014). Fagan and Najman (2005) examined associations between older siblings’ use of tobacco and alcohol and younger sibling’s use and found that older siblings’ tobacco and alcohol use were predictive of younger siblings’ use, even when accounting for a variety of shared family experiences (e.g., maternal alcohol use). While research has identified the influence of siblings on substance use behaviors, there are few studies (e.g., Fite et al., 2018) that have focused on sibling influence in rural contexts, where siblings may be especially influential because of fewer opportunities for peer socialization (Brody & Murry, 2001). The current study focuses specifically on sibling use of e-cigarettes and alcohol given that the literature on the influence of siblings on substance use among rural youth is sparse and sibling substance use behaviors have been found to influence adolescent substance use behaviors in samples of non-rural youth (e.g., Fagan & Najman, 2005; Whiteman et al., 2013).

The influence of peer behaviors becomes particularly important in adolescence, as youth begin to differentiate themselves from their families (Schuler et al., 2019). Peer delinquency specifically has been linked with youths’ substance use behaviors (Barnow et al., 2004; Hoeben et al., 2021; Trucco et al., 2011) and is perhaps a stronger predictor of substance use than family or neighborhood factors or media exposure (Ferguson & Meehan, 2011). Routinely engaging with delinquent peers in unstructured contexts increases adolescents’ risks of engaging in delinquent behaviors themselves, including the use of alcohol, cigarettes, and tobacco (Hoeben et al., 2021). One study found that peer delinquency mediates the relationship between adolescents’ own aggressive and delinquent behaviors and the frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption (Barnow et al., 2004). Peer delinquency likely contributes to youths’ substance initiation through mechanisms of social reinforcement and modeling (Trucco et al., 2011), and peer delinquency may inform youth attitudes about substance use (Ferguson & Meehan, 2011). One study found that having a persistently delinquent friend conferred risk for alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana initiation even if the friend did not use that specific substance (Widdowson et al., 2020). Though there is compelling evidence for the influence of peers’ delinquent behaviors on alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use, there is a paucity of information on the importance of peer delinquency in e-cigarette use. Higher levels of peer e-cigarette use have been found to be associated with greater e-cigarette use among adolescents (Rocheleau et al., 2020). However, peer influence on e-cigarette initiation has yet to be evaluated. Given the literature suggesting that peer delinquency more broadly confers risk for substance use, the current study evaluates how perceptions of peer delinquency contribute to the risk of e-cigarette initiation. Because of reduced access to shared mobility (Shaheen et al., 2017), youth in rural areas may have less physical access to peers (Brody & Murry, 2001), making family influences especially salient. In contrast, peers may also exert greater influence in rural settings because of the scarcity of recreational activities and increased boredom (Dew et al., 2007).

Present Study

Using multilevel survival analyses, the present study advances the early substance use literature by identifying risk of initiation over time for e-cigarettes among rural youth, which better informs the timing of prevention and intervention efforts. Further, consistent with social learning theory, the current study provides an examination of how various sources of socialization (i.e., perceptions of parental approval about substance use, sibling substance use, and peer delinquency) may contribute to risk for early initiation of e-cigarette among youth residing in a rural community, which informs targets for prevention and intervention efforts. Though perceptions of others’ behaviors (e.g., substance use) do not always align with actual behaviors (Henry et al., 2011), the present study opted to include youth perceptions, which inform social learning (Trucco et al., 2011) as mental representations of others’ behaviors (Deutsch et al., 2015). Indeed, prior research has demonstrated that perceptions of others’ substance use is a more powerful determinant of individual use than others’ actual substance use (Bauman & Fisher, 1986; Iannotti & Bush, 1992). Finally, given extant literature examining alcohol use in rural samples (Lambert et al., 2008; Rhew et al., 2011), alcohol initiation was also examined to provide further context and understanding of socialization influences on e-cigarette use among rural youth.

Consistent with trends observed in national samples (Johnston et al., 2020), we first hypothesized that risk for initiation of e-cigarette and alcohol use to increase throughout middle school. Secondly, base on prior alcohol research among urban (e.g., Sale et al., 2003) and rural youth (e.g., Fite et al., 2018), we hypothesized that greater parental approval about substance use would be associated with increased risk for initiation of both e-cigarette and alcohol use. Thirdly, consistent with research on sibling socialization among urban (Fagan & Najman, 2005; Whiteman et al., 2013) and rural youth (Fite et al., 2018), we hypothesized that sibling use would be positively associated with risk of e-cigarette and alcohol initiation. Finally, we hypothesized that higher levels of perceived peer delinquency would be associated with increased risk for e-cigarette and alcohol initiation, which corresponds with prior research on peer delinquency and substance use (e.g., Barnow et al., 2004; Hoeben et al., 2021; Trucco et al., 2011). Though we hypothesized that all social factors would contribute to the risk of e-cigarette and alcohol initiation, based on the current study’s rural sample we anticipated that family influences (i.e., parents and siblings) would be most salient in this rural sample of youth because of reduced access to peers (Brody & Murry, 2001).

Method

Participants

Middle school students (i.e., 6th through 8th grade) from a public school in a small, Midwest community participated. The school is the only public middle school in the community. Data across four school years (2016–2019) were utilized. All measures were collected at all time points. Because data were structured for an accelerated longitudinal design (ALD), six cohorts (i.e., groups of students in the same grades at the same time) across four years were generated. The data structure is described in Fig. 1.

The number of students in each cohort and for each grade and time point are listed in Table 1. Race and ethnicity were not reported by the students. However, the school’s community is predominantly White (87.7%; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). The median household income for the community is $79,427 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Youths reported their gender as male (53.2%; n = 350), female (44.5%; n = 293), or other (2.3%; n = 15). Twenty-eight participants did not report gender at any time point and were coded as missing. Since gender was included in the model as a covariate, students that listed other for gender were excluded from analyses because of their small sample size.

Procedure

The institutional review board of the researchers’ university and the participating school’s administrators approved all procedures of the current study. Surveys were administered in fall semesters of 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019. Caregivers provided consent via an online enrollment system, and consent rates for each year were 82.61%, 82.06%, 77.36%, and 79.7% respectively. Both caregivers and youth were notified that the study obtained a certificate of confidentiality from the Department of Health and Human Services, which provided protections in reporting illegal behavior. Students filled out measures using the secure platform Qualtrics while survey questions were read aloud. No school faculty or staff were in the room while students completed the surveys. Youth were not compensated for participation.

Measures

Perceived Peer Delinquency

Students self-reported on their friends’ delinquent behaviors using the 14-item Peer Affiliations Questionnaire (Fergusson et al., 1999). The questions on this scale (e.g., “Stolen or tried to steal something worth more than $50”) were dichotomous (“yes” or “no”), and greater sum scores indicated greater peer delinquency. The scale included specific questions about peers’ alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, or other drug use. Internal consistencies ranged from 0.83 to 0.89 across data collections.

Perceived Sibling Substance Use

Youth were asked to report if any of their siblings had “ever drank alcohol” or “used vaporizers or e-cigarettes” (Bahr et al., 2005), or if they had no siblings.

Perceived Parental Approval About Substance Use

Youth reported on caregivers’ views of alcohol use with questions from a previous study (Bahr et al., 2005), and a question about parental attitudes about vaporizer or e-cigarette use was added. Specifically, adolescents responded to separate questions of how wrong (1 = “very wrong”, 4 = “not wrong at all”) they think their parents would find them using alcohol or vaporizers or e-cigarettes with higher scores indicating greater approval.

Individual Substance Use

Self-reported alcohol and e-cigarette use items were taken from the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP) Student Survey, which were adapted from the California Student Survey (Pentz et al., 1989). Specifically, youth were asked: “Have you EVER had a drink of alcohol?” with alcohol referring to “beer, wine, wine coolers, grain alcohol, or hard liquor.” Adolescents were also asked: “Have you EVER used a vaporizer or e-cigarette, even just a few puffs?” There were some inconsistent reports of lifetime substance use with some students reporting lifetime use at an earlier time but no use at a subsequent time for alcohol use (4.2%, n = 29) and e-cigarettes use (1.0%, n = 7). Discrepancies were rectified by coding the first time in which a student reported use being the time of initiation.

Analysis Plan

Data Structure

Prior to analysis, data were restructured for an accelerated longitudinal design in IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Corp., 2019). Six cohorts were formed across four time points (i.e., 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019). Data for each of these cohorts were recoded so variables reflected individuals’ grades (i.e., 6th, 7th, or 8th), regardless of calendar year. The data were structured as person-period with 1162 rows and time points (i.e., repeated measures for each participant) nested within 663 participants.

Data Analysis

Data were modeled using multilevel survival analyses to determine the hazard ratio and probability of substance use initiation across middle school. The term “time” represents “grade.” Because substance use initiation was only reported at discrete intervals, we elected to use discrete-time survival analyses to model timing of initiation (Singer & Willett, 1993), and analyses accommodated both continuous and dichotomous predictors in our models (e.g., Singer & Willett, 1993). Analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team, 2020) using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015). Because the lme4 package utilizes complete case analysis, individuals’ data were only analyzed at a particular grade if all data for that observation were available (i.e., not missing), and once youth endorsed substance use, their subsequent observations were excluded from survival models. Missingness and exclusions resulted in 671 (57.75%) observations included in the e-cigarette model and 694 (59.72%) observations included in the alcohol model.

Time was coded so that the intercept estimate could be informative of the hazard odds of 6th grade (i.e., 6th, 7th, and 8th grade were coded as 0, 1, and 2 respectively). Youth’s self-report of gender was included as a time-invariant covariate and perceptions of peer delinquency, sibling substance use, and parental approval were included as time-varying covariates. Initiation of alcohol and e-cigarettes were modeled in separate survival analyses, and first report of lifetime use indicated timing of substance use initiation.Footnote 1

Both linear and quadratic trajectories were assessed in alcohol and e-cigarette models before model predictors were included. For e-cigarettes, fit indices of models with time specified as linear and quadratic (AICs = 422.1, 424.1) did not favor a particular model (Burnham & Anderson, 2002). Fit indices for alcohol models with linear and quadratic trajectories (AICs = 739.8, 741.0) likewise did not provide support for one model over another. Linear and quadratic trajectories were also assessed in alcohol and e-cigarette models with predictors included. There was no significant difference between linear and quadratic models (AICs = 374.2, 375.6) for alcohol initiation, and the quadratic model did not converge for e-cigarette initiation. Ultimately, time was specified in the models as linear, favoring parsimony.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Peer delinquency summed scores for 6th (M(SD) = 0.77(1.90)), 7th (M(SD) = 0.74(1.97)), and 8th grade (M(SD) = 0.97(2.10)) ranged from 0–14. Of youth with siblings, 23.7% (n = 88), 27.1% (n = 95), and 34.8% (n = 120) reported sibling alcohol use across 6th, 7th, and 8th grade, respectively. Sibling e-cigarette use was endorsed by 11.6% (n = 43), 13.4% (n = 47), and 17.0% (n = 57) of 6th, 7th, and 8th grade students. Between 6.0–6.9% of youth reported that they had no siblings and were treated as missing data. Of youths endorsing sibling alcohol use, 94.2% indicated that their sibling was older. For those endorsing sibling e-cigarette use, 97.9% reported that their sibling was older. Youths reported consistently disapproving parental approval about alcohol across 6th (M(SD) = 1.17(0.49)), 7th (M(SD) = 1.14(0.43)), and 8th grade (M(SD) = 1.24(0.52)). Parental approval about e-cigarettes were also consistent for 6th (M(SD) = 1.12(0.47)), 7th (M(SD) = 1.12(0.42)), and 8th grade students (M(SD) = 1.17(0.50)).

Youths’ cohort membership was correlated only with time (6th, 7th, and 8th grade), which is unsurprising given the structure of the data. Gender was negatively associated with parental approval about alcohol and e-cigarettes with boys reporting greater parental approval than girls.

E-cigarette initiation steadily increased across 6th (3.00%, n = 12), 7th (4.60%, n = 17), and 8th (6.40%, n = 23) grade. Rates of alcohol initiation were stable from 6th (11.00%, n = 43) to 7th grade (9.70%, n = 34) and 7th to 8th grade (12.00%, n = 39). Lifetime prevalence rates of e-cigarette use increased across 6th (3.00%, n = 12), 7th (5.30%, n = 20), and 8th (8.10%, n = 30). Lifetime rates of alcohol use were similar for 6th (11.00%, n = 43) and 7th (10.90%, n = 41) grade, but higher for 8th grade (17.10%, n = 63). Rates of alcohol initiation for this middle school sample correspond with rates of lifetime use of a large national study (21.7% of 8th graders; Johnston et al., 2021). Rates of e-cigarette initiation are slightly less than expected compared with the youth from same large national study (17.5% of 8th graders; Johnston et al., 2021), which may be because of the study’s entirely rural sample (Pesko & Robarts, 2017).

Survival Analysis

E-Cigarettes

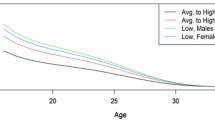

Fixed effects estimates, significance, hazard ratios, and probabilities are reported in Table 2. The exponentials of the fixed effects’ estimates were taken to produce the hazard ratios, and probabilities were computed from the hazard ratios. Hazard ratios, which we also reported as probabilities, were consulted to determine the magnitude of effects (Schober & Vetter, 2018) wherein the hazard ratio is the probability that risk of initiation will happen for every 1 unit increase in the value of the predictor. For e-cigarette use, time was a significant predictor, and risk for e-cigarette use increased from 6th to 8th grade with a 75% increased risk of e-cigarette initiation per year (see Fig. 2). Gender was not a significant predictor of e-cigarette initiation. Peer delinquency was a significant predictor of e-cigarette initiation with risk of initiation increasing 59% per unit increase of their peer delinquency score. Sibling e-cigarette use was associated with e-cigarette initiation, with an 87% increased risk of initiation for youth with a sibling who uses e-cigarettes. Finally, parental approval about e-cigarettes predicted e-cigarette initiation, with each unit increase in approval corresponding to an increased risk of e-cigarette initiation of 88%.

Alcohol

Though probability of alcohol initiation increased over time (Fig. 2), the estimate for time was non-significant. This suggests that risk for alcohol initiation did not change linearly as youth aged from 6th to 8th grade. Gender was also not predictive of alcohol use initiation. Peer delinquency was a significant predictor of alcohol use initiation. The probability was 0.57, suggesting that every unit increase in peer delinquency scores corresponded with a 57% greater risk of alcohol initiation. Sibling alcohol use was only marginally statistically associated with alcohol initiation (b = 1.03, p = 0.051). Finally, parental approval significantly predicted alcohol use, with each unit increase in parents’ approval increasing the risk of alcohol initiation 92%.

Discussion

The present study advances extant literature by identifying social risk factors for e-cigarette initiation in a rural sample of middle school-age youth within a social learning theory framework. This research directly informs the timing of prevention and intervention efforts as well as specific targets for intervention (i.e., peers, siblings, and parents). Our first hypothesis was supported for e-cigarettes, with risk of e-cigarette initiation increasing by 75% annually, which is consistent with evidence suggesting that e-cigarette use increases throughout adolescence (Johnston et al., 2020). However, estimates were non-significant for alcohol use, suggesting that risk of alcohol initiation remained elevated and stable from 6th to 8th grade. That is, youth used alcohol throughout middle school, but the risk of alcohol use initiation did not change from 6th to 8th grade. These findings contrast with prior research that shows that risk of initiation increases from early to middle adolescence (Lopez-Vergara et al., 2016). Perhaps these discrepant findings are unique to the present study’s sample (e.g., predominantly White youth from the only middle school in the community), though there is evidence that rates of lifetime use increase across middle school for rural as well as urban youth (Warren et al., 2017).

Our second hypothesis that parental approval would predict risk of initiation was supported for both e-cigarettes (and alcohol) in this rural sample of youth. Parents advance norms about substance use (Wilson & Donnermeyer, 2006), and parental approval may also be indicative of substance-positive environments (Donovan & Molina, 2011), where substances are more available, substance use is not sanctioned, or substance use is socially rewarded. Parental approval may also be related to parent substance use behaviors, which present opportunities for children to witness and model their parents’ behaviors (Rusby et al., 2018). Finally, parental attitudes about substances may also be related to parent-child communication about drug use with ongoing discourse that utilizes personal experiences and integrates consequences for substance use behaviors being most effective for prevention (Miller-Day & Dodd, 2004). While youth gradually begin to differentiate themselves from their family during adolescence (Schuler et al., 2019), parents remain powerful social influences during middle school (Salvy et al., 2014), and the present study confirmed these influences on substance use within a rural sample.

Our third hypothesis that sibling use would be associated with increased risk of initiation was supported for e-cigarette, but not alcohol, initiation. Sibling use predicted e-cigarette use, which aligns with previous findings for e-cigarette (Fite et al., 2018) and other substance use (Fagan & Najman, 2005; Maiya et al., 2023; Whiteman et al., 2013). Siblings are family members like parents but are often similar in age like peers (Stormshak et al., 2004), and siblings effectively model and reinforce substance use behaviors (Fagan & Najman, 2005; Maiya et al., 2023; Whiteman et al., 2013). However, sibling use did not predict alcohol use, which may suggest that sibling influence on alcohol use may not be as strong as other influences in this age group when evaluated alongside peer delinquency and parental approval. It is worth noting that the effect sizes for sibling use were larger than those of peer delinquency in both e-cigarette and alcohol models and that the effect was significant for e-cigarettes and nearly significant (p = 0.051) for alcohol. Though prior research has identified both peers and siblings as important agents of social learning in substance use, there is evidence that sibling deviant behaviors, compared with peer deviance, better predict substance use over time (Stormshak et al., 2004). In contrast, one study identified peer substance use as a predictor of high-volume drinking episodes and intoxication frequency at 3- and 6-month follow-up, while sibling use only predicted drinking volume at 3 months (Yurasek et al., 2019). Schuler and colleagues (2019) also found that associations between adolescent use and friend use were stronger than those between adolescents and siblings across middle and high school. Though sibling use was not significantly associated with risk of alcohol initiation, findings from the present study may lend support to the influence of siblings over peers on substance use behaviors among rural youth.

Finally, consistent with our fourth hypothesis and prior research (Barnow et al., 2004; Ferguson & Meehan, 2011; Hoeben et al., 2021; Trucco et al., 2011; Widdowson et al., 2020; Schuler et al., 2019; Yurasek et al., 2019), peer delinquency contributed to both e-cigarette and alcohol initiation in the present study. Peer delinquency likely influences substance use behaviors by increasing adolescents’ engagement in delinquent behaviors, including substance use (Hoeben et al., 2021). Peers who engage in delinquent behaviors may both model and reinforce these behaviors (Trucco et al., 2011). Furthermore, peer delinquency informs social expectations around substance use (Ferguson & Meehan, 2011; Widdowson et al., 2020), and may be more influential of these norms than family or media (Ferguson & Meehan, 2011). While peer e-cigarette use is related to greater adolescent e-cigarette use (Rocheleau et al., 2020), the present study identifies peer delinquency as a risk factor for alcohol and e-cigarette use in a rural sample where access to peers may be reduced (Brody & Murry, 2001).

As expected, within this rural sample, family factors (i.e., parent approval and sibling use) were more salient than peer delinquency for e-cigarette use, with parental approval and sibling behaviors conferring greater risk probabilities for initiation than peer delinquency. Parental approval also had a greater risk probability for alcohol initiation than peer delinquency, though sibling use was not significantly associated with risk of alcohol initiation. These findings may suggest that rural youth are especially subject to parental influences (De Haan et al., 2010), potentially because they have reduced access to peers compared with urban youth (Brody & Murry, 2001). Gender was not a significant predictor for either e-cigarette or alcohol initiation. National trends for alcohol use identify narrowing differences between genders (Johnston et al., 2020), and this discrepancy is minuscule for youth in 8th grade.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

There were several methodological strengths in this study. Firstly, we utilized an accelerated longitudinal design to combine adjacent cohorts to examine substance initiation longitudinally, which allowed us to examine age-related developmental changes (Galbraith et al., 2017). The present study’s focus on early initiation was also a particular strength since early substance initiation is linked with numerous developmental consequences (Hingson et al., 2006; Johnston et al., 2014). The study’s rural sample was a significant strength since limited research suggests that rural youth differ from urban youth in substance use prevalence (Lambert et al., 2008; Martino et al., 2008) and in e-cigarette use specifically (Dai et al., 2021). In addition to rural youth being underrepresented in substance use research, access to health services is reduced in rural areas (Mumford et al., 2019), making prevention efforts for this population essential.

The findings of the present study should be interpreted considering its limitations. Race and ethnicity were not assessed, though there is evidence of racial and ethnic differences in adolescent substance use (Johnston et al., 2021). Overall, the sample was from a racially homogenous community (87.7% White), which limits the generalizability of the findings. Six youth were excluded because of their inconsistent reports of gender or their self-report of their gender as “other.” Future studies should evaluate trends of e-cigarette and alcohol use trends among transgender or gender expansive youth. Perceptions of peer delinquency and parental approval, as opposed to perceived peer and parent substance use, were considered in the present study. Because of data collection limitations, peer delinquency, but not peer alcohol or e-cigarette use, was included as a model predictor for alcohol and e-cigarette initiation. While there are benefits of including a broader risk factor social risk factor (i.e., peer delinquency) for a more specific behavior (i.e., substance use), this is a potential limitation of the current study. Though prior research has identified peer delinquency (Barnow et al., 2004; Ferguson & Meehan, 2011; Hoeben et al., 2021; Trucco et al., 2011) and parental approval (Donovan & Molina, 2011; Fite et al., 2018; Sale et al., 2003) as risk factors for youth substance behaviors, future research may benefit from including measures with greater consistency across social influences (e.g., perceived peer, sibling, and parent substance use behaviors as well as peer and sibling delinquency). Future research may also wish to compare peer delinquency with peer substance use as predictors of substance initiation. Youth reported on their own perceptions of peer, sibling, and parents’ behaviors or approval. Though these perceptions are influential factors for substance initiation (D’Amico & McCarthy, 2006; Salvy et al., 2014), future research would benefit from the inclusion of peer, sibling, and parent self-reports of their own behaviors and approval of substances. Sibling substance use was a dichotomous predictor and did not capture the frequency or extent of sibling substance use. Having multiple siblings that use substances, having some but not all siblings that use substances, and having older versus younger siblings that use substances may all differentially contribute to risk for substance initiation. Future studies may also benefit from examining sibling gender in relation to influence on substance use. Additionally, future studies should consider whether there are differences in the influence of peers on youth with and without siblings. Finally, other individual attributes (e.g., substance willingness; Gerrard et al., 2008) and environmental factors (e.g., parental divorce; Sartor et al., 2007) have been linked with substance use among adolescents and would be informative if included in future studies timing of initiation.

Future studies should also incorporate more frequent measurement occasions (e.g., every 6 months), which would provide more information about timing of initiation. Similarly, the current study only modeled within-time social influences because of concerns that data missingness and a reduced number of time points (i.e., two time points) would present power issues for time-lagged analyses (Jóźwiak & Moerbeek, 2012). Because of limitations of the statistical package used, the present study utilized listwise deletion within time, which is robust to violations of missing completely at random (MCAR) and missing at random (MAR; Allison, 2010). Though the present study benefited from a large sample size, future studies conducting survival analyses may benefit from using imputation methods (e.g., full information maximum likelihood) to handle missing data. Additional data points would better allow antecedent social influences to be examined. Since there may be meaningful interactive effects for these model covariates, future studies should conduct theory-driven evaluations of potential interactions between gender, perceived peer delinquency, perceived sibling substance use, and perceived parental approval about substance use on youth risk for initiation.

There are several implications that can be gleaned from the present study. In the present study, e-cigarette initiation was evident as early as 6th grade and risk doubled annually throughout middle school, though overall rates remained low. Findings indicate that prevention approaches need to occur prior to middle school, and prevention efforts should continue throughout middle school. Results also indicate that peer delinquency, sibling substance use, and parental approval increase the likelihood of initiation several times over. Preventive education may focus on e-cigarettes’ negative health consequences, addictive nature, or gateway effects for traditional tobacco use to combat the influence of peers (Park et al., 2019). Successful prevention programs should incorporate parents, and combined student- and parent-based programs show promise for preventing adolescent alcohol and drug use (Newton et al., 2017). Targeted parent-child communication about alcohol may influence youth perceptions of alcohol use and reduce adolescent alcohol use (Miller-Day & Dodd, 2004; Miller-Day & Kam, 2010), so interventions aimed to facilitate communication about substance use may benefit youth and their families (Choi et al., 2017). E-cigarette findings in the present study and prior research evidence the importance of targeting sibling relationships for prevention and intervention efforts for adolescent substance use behaviors. Substance use preventive interventions should incorporate siblings and encourage siblings to engage in constructive activities with one another (Feinberg et al., 2012). Parent-focused interventions may also empower parents to manage sibling relationships by reducing sibling collusion and conflict (Low et al., 2012). Although links between social influences and substance use have been well-documented, the present study provides support for the influence of peers, siblings, and parents on early e-cigarette and alcohol initiation among rural middle school-age youth.

Data Availability

Data and R code are available upon request.

Notes

Data regarding traditional tobacco (i.e., cigarette) and marijuana use initiation were collected. However, both had inadequate numbers for survival analysis, and models were not producible. Accordingly, the current manuscript focuses specifically on e-cigarette initiation, with alcohol initiation as the comparison.

References

Allison P. D. (2010). Missing Data. In R. E. Millsap & A. Maydeu-Olivares (Eds.), Sage handbook of quantitative methods in psychology (pp. 72–89). Sage Publications Ltd.

Bahr, S. J., Hoffmann, J. P., & Yang, X. (2005). Parental and peer influences on the risk of adolescent drug use. Journal of Primary Prevention, 26(6), 529–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-005-0014-8.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Prentice-Hall.

Barnow, S., Schultz, G., Lucht, M., Ulrich, I., Preuss, U. W., & Freyberger, H. J. (2004). Do alcohol expectancies and peer delinquency/substance use mediate the relationship between impulsivity and drinking behavior in adolescence? Alcohol and Alcoholism, 39(3), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agh048.

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.

Bauman, K. E., & Fisher, L. A. (1986). On the measurement of friend behavior in research on friend influence and selection: findings from longitudinal studies of adolescent smoking and drinking. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 15(4), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02145731.

Brody, G. H., & Murry, V. M. (2001). Sibling socialization of competence in rural, single‐parent African American families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(4), 996–1008. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00996.x.

Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (2002). Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach (2nd ed.). Springer.

Chang, Y.-P., & Seo, Y. S. (2020). E-cigarette use and concurrent risk behaviors among adolescents. Nursing Outlook. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.09.005.

Choi, H. J., Miller-Day, M., Shin, Y., Hecht, M. L., Pettigrew, J., Krieger, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2017). Parent prevention communication profiles and adolescent substance use: a latent profile analysis and growth curve model. Journal of Family Communication, 17(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2016.1251920.

D’Amico, E. J., & McCarthy, D. M. (2006). Escalation and initiation of younger adolescents’ substance use: the impact of perceived peer use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(4), 481–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.010.

Dai, H., Chaney, L., Ellerbeck, E., Friggeri, R., White, N., & Catley, D. (2021). Rural-urban differences in changes and effects of tobacco 21 in youth e-cigarette use. Pediatrics, 147(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-020651.

Dawson, D. A., Goldstein, R. B., Patricia Chou, S., June Ruan, W., & Grant, B. F. (2008). Age at first drink and the first incidence of adult-onset DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(12), 2149–2160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00806.x.

De Haan, L., Boljevac, T., & Schaefer, K. (2010). Rural community characteristics, economic hardship, and peer and parental influences in early adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(5), 629–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609341045.

Deutsch, A. R., Chernyavskiy, P., Steinley, D., & Slutske, W. S. (2015). Measuring peer socialization for adolescent substance use: a comparison of perceived and actual friends’ substance use effects. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(2), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2015.76.267.

Dew, B., Elifson, K., & Dozier, M. (2007). Social and environmental factors and their influence on drug use vulnerability and resiliency in rural populations. Journal of Rural Health, 23, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2007.00119.x.

Donovan, J. E., & Molina, B. S. G. (2011). Childhood risk factors for early-onset drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(5), 741–751. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2011.72.741.

Fagan, A. A., & Najman, J. M. (2005). The relative contributions of parental and sibling substance use to adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use. Journal of Drug Issues, 35(4), 869–883. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260503500410.

Feinberg, M. E., Solmeyer, A. R., & McHale, S. M. (2012). The third rail of family systems: sibling relationships, mental and behavioral health, and preventive intervention in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15, 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0104-5.

Ferguson, C. J., & Meehan, D. C. (2011). With friends like these…: peer delinquency influences across age cohorts on smoking, alcohol and illegal substance use. European Psychiatry, 26(1), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.09.002.

Fergusson, D. M., Woodward, L. J., & Horwood, L. J. (1999). Childhood peer relationship problems and young people’s involvement with deviant peers in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(5), 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021923917494.

Fite, P. J., Cushing, C., & Ortega, A. (2020). Three year trends in e-cigarettes among Midwestern middle school age youth. Journal of Substance Use, 25(4), 430–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2020.1725163.

Fite, P. J., Cushing, C. C., Poquiz, J., & Frazer, A. L. (2018). Family influences on the use of e-cigarettes. Journal of Substance Use, 23(4), 396–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2018.1436601.

Galbraith, S., Bowden, J., & Mander, A. (2017). Accelerated longitudinal designs: an overview of modelling, power, costs and handling missing data. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 26(1), 374–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280214547150.

Gerrard, M., Gibbons, F. X., Houlihan, A. E., Stock, M. L., & Pomery, E. A. (2008). A dual-process approach to health risk decision making: the prototype willingness model. Developmental Review, 28(1), 29–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2007.10.001.

Henry, D. B., Kobus, K., & Schoeny, M. E. (2011). Accuracy and bias in adolescents’ perceptions of friends’ substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 25(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021874.

Hingson, R. W., Heeren, T., & Winter, M. R. (2006). Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(7), 739–746. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739.

Hoeben, E. M., Osgood, D. W., Siennick, S. E., & Weerman, F. M. (2021). Hanging out with the wrong crowd? The role of unstructured socializing in adolescents’ specialization in delinquency and substance use. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 37(1), 141–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09447-4.

Iannotti, R. J., & Bush, P. J. (1992). Perceived vs. actual friends’ use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and cocaine: which has the most influence? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 21(3), 375–389

IBM Corp. Released (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Johnston, L. D., Miech, R. A., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. E., & Patrick, M. E. (2020). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2019: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED604018.

Johnston, L. D., Miech, R. A., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Patrick, M. E. (2021). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2020: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED611736.

Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Miech, R. A. (2014). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2013. Volume 1, secondary school students. Institute for Social Research. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED578546.

Jóźwiak, K., & Moerbeek, M. (2012). Power analysis for trials with discrete-time survival endpoints. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 37(5), 630–654. https://doi.org/10.3102/1076998611424876.

Lambert, D., Gale, J. A., & Hartley, D. (2008). Substance abuse by youth and young adults in rural America. The Journal of Rural Health, 24(3), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00162.x.

Li, C., Pentz, M. A., & Chou, C.-P. (2002). Parental substance use as a modifier of adolescent substance use risk. Addiction, 97(12), 1537–1550. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00238.x.

Lopez-Vergara, H. I., Spillane, N. S., Merrill, J. E., & Jackson, K. M. (2016). Developmental trends in alcohol use initiation and escalation from early- to middle-adolescence: prediction by urgency and trait affect. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 30(5), 578–587. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000173.

Low, S., Shortt, J., & Snyder, J. (2012). Sibling influences on adolescent substance use: the role of modeling, collusion, and conflict. Development and Psychopathology, 24(1), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579411000836.

Maiya, S., Whiteman, S. D., Serang, S., Dayley, J. C., Maggs, J. L., Mustillo, S. A., & Kelly, B. C. (2023). Associations between older siblings’ substance use and younger siblings’ substance use intentions: indirect effects via substance use expectations. Addictive Behaviors, 136, 107493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107493.

Marsiglia, F. F., Kulis, S., Yabiku, S. T., Nieri, T. A., & Coleman, E. (2011). When to intervene: elementary school, middle school or both? Effects of keepin’it REAL on substance use trajectories of Mexican heritage youth. Prevention Science, 12, 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-010-0189-y.

Martino, S. C., Ellickson, P. L., & McCaffrey, D. F. (2008). Developmental trajectories of substance use from early to late adolescence: a comparison of rural and urban youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69(3), 430–440. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2008.69.430.

McCabe, S. E., West, B. T., & McCabe, V. V. (2018). Associations between early onset of e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking and other substance use among US adolescents: a national study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 20(8), 923–930. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntx231.

Miech, R., Leventhal, A., Johnston, L., O’Malley, P. M., Patrick, M. E., & Barrington-Trimis, J. (2021). Trends in use and perceptions of nicotine vaping among US youth from 2017 to 2020. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(2), 185. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5667.

Miller-Day, M., & Dodd, A. H. (2004). Toward a descriptive model of parent–offspring communication about alcohol and other drugs. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407504039846.

Miller-Day, M., & Kam, J. A. (2010). More than just openness: Developing and validating a measure of targeted parent–child communication about alcohol. Health Communication, 25(4), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410231003698952.

Mumford, E. A., Stillman, F. A., Tanenbaum, E., Doogan, N. J., Roberts, M. E., Wewers, M. E., & Chelluri, D. (2019). Regional rural‐urban differences in e‐cigarette use and reasons for use in the United States. Journal of Rural Health, 35(3), 395–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12333.

Newton, N. C., Champion, K. E., Slade, T., Chapman, C., Stapinski, L., Koning, I., Tonks, Z., & Teesson, M. (2017). A systematic review of combined student- and parent-based programs to prevent alcohol and other drug use among adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Review, 36(3), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12497.

Noland, M., Rayens, M. K., & Hahn, E. J. (2017). Current use of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes among us high school students in urban and rural locations: 2014 National Youth Tobacco Survey. American Journal of Health Promotion, 32(5), 1239–1247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117117719621.

Ortega, A., Sutton, M., McConville, A., Cushing, C. C., & Fite, P. J. (2021). Longitudinal investigation of the bidirectional associations between initiation of e-cigarettes and other substances in adolescents. Journal of Substance Use, 26(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2020.1766129.

Park, E., Kwon, M., Gaughan, M. R., Livingston, J. A., & Chang, Y.-P. (2019). Listening to adolescents: their perceptions and information sources about e-cigarettes. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 48, 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2019.07.010.

Pea, R. D. (1993). Practices of distributed intelligence and designs for education. In G. Salomon (Ed.), Distributed cognitions: psychological and educational considerations (pp. 47–87). Cambridge University Press.

Pentz, M. A., Brannon, B. R., Charlin, V. L., Barrett, E. J., MacKinnon, D. P., & Flay, B. R. (1989). The power of policy: the relationship of smoking policy to adolescent smoking. American Journal of Public Health, 79(7), 857–862. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.79.7.857.

Pesko, M. F., & Robarts, A. M. T. (2017). Adolescent tobacco use in urban versus rural areas of the United States: the influence of tobacco control policy environments. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.019.

Pomery, E. A., Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., Cleveland, M. J., Brody, G. H. & Wills, T. A. (2005). Families and risk: Prospective analyses of familial and social influences on adolescent substance use. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(4), 560–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.560.

R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/.

Rende, R., Slomkowski, C., Lloyd-Richardson, E., & Niaura, R. (2006). Sibling Effects on Substance Use in Adolescence: Social Contagion and Genetic Relatedness. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 19, 611–618. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.611.

Rhew, I. C., Hawkins, J. D. & Oesterle, S. (2011). Drug use and risk among youth in different rural contexts. Health and place, 17(3), 775–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.02.003.

Rocheleau, G. C., Vito, A. G., & Intravia, J. (2020). Peers, perceptions, and e-cigarettes: a social learning approach to explaining e-cigarette use among youth. Journal of Drug Issues, 50(4), 472–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042620921351.

Rusby, J. C., Light, J. M., Crowley, R., & Westling, E. (2018). Influence of parent–youth relationship, parental monitoring, and parent substance use on adolescent substance use onset. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(3), 310. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000350.

Sale, E., Sambrano, S., Springer, J. F., & Turner, C. W. (2003). Risk, protection, and substance use in adolescents: a multi-site model. Journal of Drug Education, 33(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.2190/LFJ0-ER64-1FVY-PA7L.

Salvy, S.-J., Pedersen, E. R., Miles, J. N. V., Tucker, J. S., & D’Amico, E. J. (2014). Proximal and distal social influence on alcohol consumption and marijuana use among middle school adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 144, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.012.

Sartor, C. E., Lynskey, M. T., Heath, A. C., Jacob, T., & True, W. (2007). The role of childhood risk factors in initiation of alcohol use and progression to alcohol dependence. Addiction, 102(2), 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01661.x.

Schober, P., & Vetter, T. R. (2018). Survival analysis and interpretation of time-to-event data: the tortoise and the hare. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 127(3), 792. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003653.

Schuler, M. S., Tucker, J. S., Pedersen, E. R., & D’Amico, E. J. (2019). Relative influence of perceived peer and family substance use on adolescent alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use across middle and high school. Addictive Behaviors, 88, 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.025.

Shaheen, S., Bell, C., Cohen, A., Yelchuru, B., & Hamilton, B. A. (2017). Travel behavior: shared mobility and transportation equity (No. PL-18-007). U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. Office of Policy & Governmental Affairs. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/63186.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (1993). It’s about time: using discrete-time survival analysis to study duration and the timing of events. Journal of Educational Statistics, 18(2), 155–195. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986018002155.

Stormshak, E. A., Comeau, C. A., & Shepard, S. A. (2004). The relative contribution of sibling deviance and peer deviance in the prediction of substance use across middle childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32(6), 635–649. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JACP.0000047212.49463.c7.

Trucco, E. M., Colder, C. R., & Wieczorek, W. F. (2011). Vulnerability to peer influence: a moderated mediation study of early adolescent alcohol use initiation. Addictive Behaviors, 36(7), 729–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.008.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Explore Census Data. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/.

Van Ryzin, M. J., & Dishion, T. J. (2014). Adolescent deviant peer clustering as an amplifying mechanism underlying the progression from early substance use to late adolescent dependence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(10), 1153–1161. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12211.

Warren, J. C., Smalley, K. B., & Barefoot, K. N. (2017). Recent alcohol, tobacco, and substance use variations between rural and urban middle and high school students. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 26(1), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828X.2016.1210550.

Whiteman, S. D., Becerra, J. M., & Killoren, S. E. (2009). Mechanisms of sibling socialization in normative family development. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2009(126), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.255.

Whiteman, S. D., Jensen, A. C., & Maggs, J. L. (2013). Similarities in adolescent siblings’ substance use: testing competing pathways of influence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74(1), 104–113. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2013.74.104.

Whiteman, S. D., Jensen, A. C., & Maggs, J. L. (2014). Similarities and differences in adolescent siblings’ alcohol-related attitudes, use, and delinquency: evidence for convergent and divergent influence processes. Journal of youth and adolescence, 43, 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9971-z.

Widdowson, A. O., Ranson, J. A., Siennick, S. E., Rulison, K. L., & Osgood, D. W. (2020). Exposure to persistently delinquent peers and substance use onset: a test of Moffitt’s social mimicry hypothesis. Crime & Delinquency, 66(3), 420–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128719869190.

Wilson, J. M., & Donnermeyer, J. F. (2006). Urbanity, rurality, and adolescent substance use. Criminal Justice Review, 31(4), 337–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016806295582.

Yurasek, A. M., Brick, L., Nestor, B., Hernandez, L., Graves, H., & Spirito, A. (2019). The effects of parent, sibling and peer substance use on adolescent drinking behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1251-9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all legal guardians of minor participants included in the study, and guardians provided informed consent regarding to publishing participant data.

Ethics Approval

Approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the University of Kansas. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hesse, D.R., Fite, P.J. Sources of Socialization in E-Cigarette Initiation Among Rural Middle School-Age Youth. J Child Fam Stud (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02705-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02705-x