Abstract

This essay demonstrates how market prices for contemporary art flourished in the late nineteenth century, fell after 1900, and rose again in the 1960s. This discovery stands in contrast to previous twentieth-century art market studies, which have depended on the sales prices achieved by modernist and avant-garde artists. The artists who were financially successful before 1900 have been dismissed as commercial or academic. Arguing for the importance of high-end sales, the paper mostly relies on the primary and secondary premium sales data belonging to the Paris gallery founded by Adolphe Goupil and the New York gallery founded by Michael Knoedler. Using CPI to convert prices over time, premium sales prices for Old Master, Near Contemporary, and Contemporary Art are compared over a ninety-year period, from the 1860s to the end of the 1950s. Among the discoveries yielded by these data is how close prices for contemporary art matched prices for Old Master painting until the very end of the nineteenth century. The data also indicates that many more contemporary artists benefited from high prices during the nineteenth century than later living artists achieved until late in the twentieth century. What appears to have contributed to the rise and fall and rise again of contemporary art prices is the corresponding rise and fall and rise again of interest in contemporary art by superrich collectors. An international market fueled by such collectors appears have been essential in creating high prices for contemporary art.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The name of Goupil is henceforth inseparable from the history of French Art. He symbolizes and represents the entire period from Paul Delaroche to Gérôme and Detaille, and when account is taken of the great talents called forth and developed during that time, it will certainly be regarded as one of the most flourishing art periods in the history of the world; and never before had artists met with so full and ready a recognition of their abilities.

From Frédéric Masson’s obituary for Adolphe Goupil (Masson, 1893, 221)

The success of the sale was an event. The great Picasso, “Family of Clowns,” held the record as a price of 11,600 francs, sold to Germans. (I mean by record, the prices, hitherto paid for the Young people; there is no question of Meissonier, Detaille, Carolus Duran and other officials.)

The dealer Berthe Weill, describing the success of the Le Peau de L’Ours auction in 1914 (Weill, 2021, 107)

The market for contemporary painting in the period between 1860 and 1890 brought many artists higher sales prices for their work than contemporary artists would experience again until the 1960s. Gerald Reitlinger, in his classic study The Economics of Taste, devoted a chapter to what he termed “The Golden Age of the Living Painter. 1860–1914” (Reitlinger, 1961). Reitlinger’s account mixed anecdotal discussions of individual artists (predominately British), with some notable prices their works achieved at auction. His analysis was colored by his reliance primarily on English auction results and by an unsystematic use of his price data. Moreover, Reitlinger’s contention that this was indeed a golden age for living artists has largely gone unheeded.Footnote 1 Subsequent scholarship has mostly equated the history of modern art markets with the history of modern art. This was not the story Reitlinger told. The account that follows refines and further substantiates Reitlinger’s study. It rejects the idea that the contemporary art market has its origins in modernist art—in other words, the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists and their dealers—and that a direct line runs between the early market for modernist paintings and the record sales prices we witness for contemporary art today.Footnote 2

The thriving contemporary art market for less innovative painting that developed in the second half of the nineteenth century dominated the international trade in contemporary art. The great Salon or academic artists of the era, painters such as Ernest Meissonier, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and William Bouguereau, benefited far more from their market than almost any living modernist painter experienced for more than another half century, including the most successful modern artists, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. This market was driven by superrich American and British collectors.Footnote 3 Until the end of the century, their patronage made many artists wealthy and sometimes very wealthy.

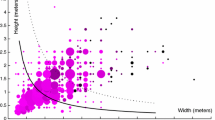

Broadly considered, the market for contemporary art over time has been “U”-shaped, with very high prices for contemporary art from the 1860s to the 1890s. Prices for living artists then started to fall during the 1890s and fell even further between the two world wars, before rising again near the end of the 1950s. Taken in aggregate, contemporary artists during the later nineteenth century sold works for prices nearly equivalent to or occasionally surpassing prices for Old Master art. After 1900, and until the 1960s, Old Master prices far surpassed contemporary art prices. Also, many more artists participated in substantial sales during the later nineteenth century than did post-1900 artists until the 1980s. Today’s super-heated global art market has enabled many artists to sell their work at a premium price. Consequently, the number of successful participants in the contemporary art market has acquired a similar “U”-shape over time.Footnote 4

In support of these claims, this paper makes relative worth comparisons between significantly separated time periods. This is a challenging task. What would be the equivalent value for a painting that sold in 1875 for 20,000 francs in, say, 1925 dollars? To answer this question, one must first render francs into dollars at 1875 exchange rates.Footnote 5 One then might compare 1875 dollars to 1925 dollars by adjusting for inflation using the CPI. As the authors of the website “MeasuringWorth” have argued, there are multiple other metrics that could be used to create worth comparisons that would provide very different results (Officer & Williamson, 2022). “MeasuringWorth” offers five variables to determine the relative worth of a commodity (real price, relative value in consumption, labor value, income value, and economic share). For the relative worth of incomes, “MeasuringWorth” uses another five metrics: real wages or real wealth, household purchasing power, relative labor earnings, relative income, and relative output (Williamson, 2022). Using the CPI index, $10 in 1875 would be equivalent to $16.50 in 1925. Using as an index the GDP deflator, the relative value in 1925 jumps to $18.40. Calculations relying on the relative wage or income index measured against the relative wages of unskilled labor turns $10 into $32.30 in 1925 (more if skilled labor is the metric). Other indices yield even higher relative worth valuations. This paper relies on the CPI to estimate inflated worth, but with the understanding that the relative value of paintings sold between 1860 and 1890 may be greater, perhaps significantly greater, than the CPI index would indicate. Even so, using the CPI alone, this paper’s findings support the U-curve description of the contemporary art market since 1860. The use of different metrics would only affect how high each side of the “U” might be.

1 Disaggregating the Getty stock books

The primary art market is notoriously secretive. Unequal access to information is to the dealer’s advantage. Art dealers have also long been wary of publishing prices should those prices show a decline in the secondary market, and particularly when their artist’s works are at auction.Footnote 6 In order to understand contemporary art sales in the face of so little transparency, art market scholars have usually depended upon what can be learned through auction prices. Auction data may tell us a great deal about art as an investment, but comparatively little about the financial benefits of the market for the makers of art. Auction data also usually suffers from recency biases. Historical art auction results are far less accessible and convertible into data sets than auction data from the last fifty years.

The Getty Research Institute has provided a powerful alternative to existing auction data by digitizing the stock books belonging to two major commercial galleries in their possession, the Pars gallery Goupil (and its successor Boussod, Valadon et Cie) and the New York gallery Knoedler (Helmreich, 2020; Penot, 2010; Serafini, 2016). The GRI transcribed all the stock book transaction data and posted the data sets online.Footnote 7 These data help pull back the curtain on primary and secondary art transactions for two of the most important commercial art galleries in their respective cities and time periods. From these data, we can often learn who were the buyers and sellers in this trade, what they bought and when, how many artists participated in these markets, and how often works sold for high prices.

Research so far that uses the Getty data sets has aggregated the data to understand, for example, Goupil’s overall business practices or the network of dealers and collectors that contributed to the flow of paintings across national borders (Penot, 2017; Serafini, 2016). There are, however, two clear advantages to disaggregating these data. The first advantage is merely mechanical. By concentrating only on the most expensive transactions, one can better clean up the data, finding and removing duplicate entries and correcting recording errors (either by the transcribers or in the original stock books). The latter typically involves identifying the appropriate currency that makes sense in a transaction. For example, one finds in the Knoedler stock books, where the gallery is constantly switching between francs, pounds and dollars, a sales price that might be listed in francs, whereas the gallery made the purchase in pounds. A transaction, therefore, might be recorded as a £3000 purchase yet a 4000 fr. sale. If the recorded sales price was accurate, the gallery would have taken a very substantial loss on the sale.

More importantly, in treating all commercial transactions by a gallery as more or less equal, one overlooks the central fact that art and art markets are normally vertically constructed. At any given moment only a handful of artists, a generation’s blue-chip artists, achieve immediate or eventual very high prices for their works as well as lasting reputations.Footnote 8 Below these privileged few are a larger number of artists whose art may experience significant success in the market and some local or national repute. Further down is the great mass of artists who may or may not earn a living from their work and whose careers are mostly forgotten. In parallel, art history, until very recently, has been extremely canonical (Jensen, 2007). Only a few artists in any one period or location are considered very important; other artists might or might not be mentioned in the art historical literature, and most artists are never mentioned. Whether this hierarchical structure will persist in the digital age is not yet known.

By isolating high-end sales data from the mass of these dealers’ commercial transactions, we can most clearly discern the artists who were the prime beneficiaries of the market and the impact that the superrich collectors had on their careers. The term “superrich” is used here rather than “robber barons,” among possible designations, because it is inclusive of those whose wealth was inherited or acquired outside the banking, transportation, and steel production industries normally associated with the late nineteenth-century robber barons. The term superrich simply expresses the concentration, by whatever means, of great wealth in the hands of comparatively few people. Collectors who buy an artist’s work at low prices might sustain an artist economically. But the importance of superrich collectors is best expressed by their willingness to pay much more than the common market price for an artist’s work.Footnote 9 These “overpays” are what made quite a few artists rich. The superrich today are similarly impacting the market, and it is they who are driving sales prices to unprecedented heights.

2 High-end art sales

What is a high-end or premium sale? This study takes as a basic premise that 20,000 fr. was regarded in France during the 1860s–1880s as a standard price for an exemplary contemporary painting, one worthy of entry into a museum collection. In 1872 Edouard Manet created a personal price list for many of the artist’s most important pictures painted during the prior decade. At the time, the highest recorded price Manet had received for one of his paintings was 1500 fr. In his inventory, Manet priced two of his paintings at 25,000 fr., the 1863 Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and the largest version of L’execution de Maximilien de Mexico, 1868 (Mannheim Kunsthalle). He set the price for his most scandalous painting, Olympia (Musée d’Orsay, Paris), shown at the Salon of 1865, at 20,000 fr. Notably, when Claude Monet in 1890 organized a subscription to purchase the Olympia from Manet’s family with the intention of donating the painting to the Louvre, 20,000 fr. was the agreed purchase price. In 1872, 20,000 fr. could be exchanged for about $4243; in 1890, 20,000 fr. would have exchanged for about $3826.

We can also think about 20,000 fr. in terms of its contemporary buying power. Art scholars have tried to make concrete for modern audience’s income purchasing power in the late nineteenth century. A popular metric was created by the editors of the online correspondence of Vincent van Gogh (Jansen et al., 2009). They determined that Vincent’s brother, the art dealer Theo van Gogh, received a base salary from the Boussod Valadon gallery, beginning in 1882, of 4000 fr. per year. Theo also received a 7.5% bonus on the net profits from the branch gallery he managed. Between 1882 and 1890, Theo’s annual bonuses ranged from 6881 fr., to 9840 fr. Overall, then, he earned on average about 12,000 fr. per year. This sum could then be applied to Theo van Gogh’s lifestyle. On 12,000 fr., he maintained a large apartment in a fashionable part of Paris. He was able to employ a maid and he was able to send money home to his parents and support his brother. Vincent received an average of 1750 fr. annually. As a comparison, the van Gogh editors noted that Vincent’s friend, the postman Joseph Roulin, fed and housed his family of five on just 135 fr. a month (1620 fr. annually). It is a bit surprising to discover that Vincent, because of Theo’s assistance, enjoyed a better income than this minor French official.

Similar measures can be found that help provide a sense of what money could buy in lifestyle benefits in the late nineteenth century. For example, the British historian Eric Hobsbawm observed that the father of the economist John Maynard Keynes, who was also an economist and a lecturer at Cambridge University, possessed an annual income of about £1000, which was then equivalent to about 25,000 fr. (Hobsbawm, 1989). From this sum, John Neville Keynes annually saved £400 and lived off the remaining £600 (about 15,500 fr.). Keynes was able to employ three full-time servants, one governess, and take two holidays a year. Hobsbawm noted that a month-long vacation in Switzerland in 1891 cost the elder Keynes £68 (about 1760 fr.). From these anecdotal accounts, we can generally conclude that between the 1870s and the First World War, the range of roughly 12,000 to 25,000 fr. annually might be considered a comfortably middle-class income.

A US government report on immigration published in 1898 calculated the average wage of all American workers in 1881 compared to European workers’ wages.Footnote 10 On average, American workers were paid $15.84 a week, or an annual wage, depending on the number of weeks worked, of around $830. This would have been the equivalent of about 4600 fr. A more skilled worker, such as a carpenter working in St. Louis, would have earned what would have been approximately 6700 fr. annually—a working class to lower middle-class income. Table 1 summarizes these incomes and projects a relative class standing per income level.

Using the data from Table 1 as benchmarks I established price points for high-end painting that begin with $1000 in 1865 (3324 fr.). This represents an expensive painting, roughly equivalent to the annual income of an unskilled American worker. $5000 in 1865 exchanged for 16,620 fr., but during the 1870s and later, exchanged for more than 20,000 fr.Footnote 11 It was also more than an annual middle-class French income during these years. Since 1886, the English Art Journal tracked the most expensive auction prices in London.Footnote 12 They set the base price at £1400 for the top end of the London auction market. £1400 was equivalent in 1890 to $6758 or 35,327 fr. At $10,000, we reach sales prices that are significantly greater than the annual upper middle-class income of Professor Keynes. Finally, $15,000 or above is the price of a truly expensive painting. The average price for paintings that sold at the top end of English auctions during the Nineties was £3275 or $16,046. Adjusting only for CPI $15,000 in 1865 would represent about $25,400 in 1955. If we use the relative wages of unskilled labor as an index the equivalent of $15,000 in 1865 would be about $164,000 in 1955. To put these metrics in further perspective, the highest price paid for any painting at an English auction during the 1890s was £11,550 or about $56,595, for a portrait by Joshua Reynolds. The highest Goupil sales price during the same decade was for about $42,373 for a Meissonier. Knoedler’s highest sales price for a living artist during this decade was $15,000, for a painting by Jehan Vibert. (The gallery also sold in 1899 a Camille Corot painting, who died in 1876, for $40,000.)

3 Goupil’s high-end market for contemporary art

Adolphe Goupil’s gallery, from the beginning of the 1860s to the end of the 1880s, was the most successful art gallery of its day (Penot, 2017). Its success was based on volume (David et al., 2020) and trading in paintings by contemporary artists. The almost 8500 sales during the 1870s alone in Table 2 does not include the many paintings the firm failed to sell. Goupil initially specialized in primary market sales. Goupil’s business strategy was to steadily add artists to its stable. When artists proved they could sell, Goupil bought in quantity and often negotiated contracts with the artists.Footnote 13 When artists failed to sell immediately, they were quickly abandoned (Serafini, 2013). Goupil catered to the most popular tastes. If a certain formula sold well, Goupil brought into the gallery new artists who could paint similar subjects in a similar style. The gallery favored paintings that were highly detailed and where the artist’s touch was hidden behind the paintings’ highly finished surfaces.Footnote 14 Goupil chose painters of pretty, fashionably dressed women in elegant interiors, as well as painters of exotic scenes, mostly of Orientalist subject matter, such as harems, Arab horsemen, and of urban landscapes. Historical genre scenes and Napoleonic-era military pictures were also very popular with Goupil’s clients. Finally, the gallery did a brisk business in pastoral genre and landscape scenes. These were as remote from the reality of the businessmen who bought such paintings as were Arab horsemen hunting lions. Goupil’s collectors found all these paintings easy to understand and the craftsmanship that went into them easy to appreciate.

The gallery was also an early pioneer in the international art trade. Foreign visitors attracted by the official Salon held every spring would visit Goupil’s various Paris branches, to buy artists featured at the Salon or similar artists who may have debuted at Goupil’s. The gallery extended its international presence through a network of galleries that were either Goupil branches or were dealers and agents who consistently bought from Goupil. As one example, Goupil sold at least 343 paintings by Gérôme. Of these, a minimum of 171 (about half of all Gérôme’s paintings) were purchased by Continental, British, or American art dealers. Goupil made more money selling Gérôme’s paintings directly to collectors—over 3.2 million fr. at an average of 23,166 fr.—but they still made over 2.4 million fr. in sales to other art dealers, averaging 14,157 fr. per transaction. In this way, contemporary art flowed through Goupil’s Paris galleries from and to major cities like London, New York, Boston, and the Hague.

Table 2 provides a long view of Goupil’s high-end sales, from the 1860s to the end of the century. It describes Goupil’s high-end sales by decade compared to total sales and adjusted for CPI using MeasuringWorth’s purchasing power calculator.Footnote 15 Through Table 2, we can trace the evolution of Goupil’s high-end trade. Table 2 distinguishes between only three types of paintings, without regard to style, subject matter, or size. “Contemporary Paintings” are pictures Goupil sold, while the artist was alive. “Near Contemporary Paintings” were sold within thirty years following an artist’s death, and “Old Master Paintings” were sold more than thirty years after an artist’s death. After thirty years, judgments about the significance of an artist’s work typically begin to harden and reputations once achieved are rarely reversed. “Near Contemporary Paintings” on the other hand is the period in the afterlife of an artist’s work where prices are in flux. Some artists fall into obscurity gradually after their death. Other artists’ work, which may not have sold well during their lifetimes, rise in value after death and continue to rise in price long after thirty years have passed.

Prior to the 1880s Near Contemporary and Old Master paintings represented less than 3% of Goupil’s sales. And the relative number of premium sales was small in proportion to their overall market. One notes how premium sales steadily rose as the gallery became increasingly involved in the secondary market. Correspondingly, Near Contemporary artists, such as the Barbizon landscape painters who began to die off in the 1860s and 1870s, came to represent a significant portion of the gallery’s high-end sales from the 1880s forward. Many living artists also saw their work increase in value even up to the end of the century.

A remarkable number of international artists benefited directly from Goupil’s business model (David et al., 2020). Goupil purchased twenty or more paintings from 244 artists, representing ten different nationalities. Not all these artists made a fortune working with Goupil, but a significant number did. Table 3 lists Goupil’s top twenty of these artists ranked by total purchase price.Footnote 16 It should be noted that purchase prices do not necessarily indicate what the artist received. We know that Goupil signed contracts with some artists in which the artist would receive half of the agreed upon purchase price and half of whatever the painting sold for above that price (Serafini, 2013). Other artists, such as Gérôme, likely received nearly the full benefit of their purchase prices. Gérôme’s direct revenue from Goupil of over 2.5 million francs in 1880 prices would have a relative income worth of at least $100 million today. Even at the bottom end of the top twenty, the Belgian painter Florent Willems’s income, if he received most of the purchase price, would amount to about $1.5 million in inflated worth today. If measured by relative income worth, this figure rises to at least $12 million. Over a hundred artists who sold twenty or more paintings to Goupil accumulated purchase prices of over 75,000 francs. Adjusted for inflation, this figure would fall a little below $500,000 in inflated worth or over $3 million in relative income worth today.

Goupil’s international connections and enormous profits achieved in concert with artists immediately popular with his clients set the firm apart from galleries like Paul Durand-Ruel’s. In its heyday, British and American dealers and collectors bought in greater quantity and often at much higher prices works by artists handled by Goupil than did French collectors. Durand-Ruel, subsequently famous as the Impressionists’ dealer, centered his business instead around Paris’ auction houses. Much of the dealer’s autobiography (Durand-Ruel, 2014) recounts his interactions with the auction houses and the changing prices at auction for the artists he promoted. Durand-Ruel often repurchased paintings at auction, either for the purpose of an immediate sale, or to bolster an artist’s prices at auction.Footnote 17 This fact, however, is one of the least understood aspects of Durand-Ruel’s business model.Footnote 18 Even less noticed is how the dealer’s attachment to the auction houses led him to cater primarily to a domestic market. Goupil, conversely, sent so many of the gallery’s paintings abroad that only infrequently did these pictures reappear in a Paris auction. Not surprisingly, Durand-Ruel’s efforts to develop lasting international connections did not prove fruitful until the very end of the 1880s.

These contrasting dealer strategies have some important consequences. Many of Goupil’s artists did much better financially in the short-term than did Durand-Ruel’s artists. On the other hand, most Goupil artists had little staying power in the marketplace. The gallery was interested in what immediately sold, not in what was innovative. Durand-Ruel, in contrast, learned from the secondary market for Barbizon painting to play the long game. He was tenacious in his commitment to the artists he purchased. However, his very substantial spending on Barbizon painting made it difficult for the dealer to support financially the Impressionists until after they were well into their careers. Durand-Ruel’s investments in both the Barbizon and the Impressionist painters eventually paid off once he was able to internationalize his market. We can see how Goupil’s approach shared financial benefits with the gallery’s artists, whereas Durand-Ruel’s approach largely benefited the dealer.

A good example of these differences can be found in the comparison between the Italian painter Giovanni Boldini, who initially sold through Goupil, and Manet, whose work Durand-Ruel bought in volume. Boldini, before ever showing at the Salon and without achieving any notice from contemporary critics, managed to sell to Goupil in 1872 and 1873 57,950 fr. worth of paintings. And these were very small paintings. Manet by comparison enjoyed massive critical attention and had often showed at the Salon, albeit without honors. And the exhibitions of the Déjeuner sur l’herbe in 1863 and the Olympia in 1865 caused scandals. Yet neither notoriety nor the support Manet received from some major art critics lead to significant sales. Thus, at the end of 1872, Durand-Ruel was able to purchase from Manet many of the artist’s most important, large-format paintings from the 1860s, including some that had been shown at the Salon. For all of them, Durand-Ruel paid a mere 51,000 fr.

During the 1870s Boldini sold Goupil 130,850 fr. worth of paintings. Unlike Manet, Boldini benefited from anglophone collectors and dealers. At the beginning of the artist’s relationship with Goupil (1872–1873), Boldini’s sales to foreign dealers and collectors generally ranged between 1000 fr. and 6000 fr. Among these, however, were several exceptional sales, in which a Boldini painting sold for a price much higher than his other pictures. The American retailer A.T. Stewart bought what should be considered a very typical Boldini painting for 17,500 fr., much more than the artist’s current market price. A year later he bought another Boldini for 16,000 fr. In both cases, he paid at least 10,000 fr. more than the current market rate for a Boldini. Remember that 10,000 fr. was almost equal to Theo van Gogh’s annual salary. The cost of these purchases meant little to Stewart. During the 1860s the merchant earned on average two million dollars per year, equivalent to over eleven million francs.Footnote 19 The Boldini purchases signaled Stewart’s social status, his position vis-a-vis other American art collectors, claims about the importance of the works purchased as premium examples of an artist’s production, and the collector’s taste in identifying the works as such. It did not matter whether a painting was an exceptional work by Boldini or not; what impressed was the price paid.

As for Manet’s market, Durand-Ruel would never again make a major purchase directly from the artist. Later, in the 1890s, the dealer began to buy back from collectors almost all his original Manet purchases, which he then often sold to mostly foreign collectors at enormous profit. In the meantime, Manet, before his untimely death in 1883, experienced few sales and of these few approached the prices Boldini’s paintings received, much less the prices achieved by a Salon celebrity like Meissonier. Manet’s famous posthumous auction in 1884, which included forty-plus paintings as well as numerous pastels and drawings, yielded a total of about 100,000 fr. As a comparison, almost a decade earlier, an auction involving far fewer paintings by the recently deceased Spanish artist Mariano Fortuny was received by dealers and collectors with “delirious enthusiasm.” It yielded over 800,000 fr. (Tabarant, 1947, 264). Fortuny was a prototypical Goupil artist, already popular with superrich American and British collectors. In 1884 and for several years after, this same class of collectors showed no interest in Manet’s art. Throughout Manet’s life and for about five years after his death, the artist’s prices remained relatively flat. Only when foreign collectors began to buy Manet’s paintings did the artist’s prices rapidly rise.

4 The evolution of the Knoedler market

One of Goupil’s major avenues for sales was the Knoedler gallery. Michael Knoedler started out as the manager of Goupil’s branch gallery in New York. Once independent, Knoedler continued to be the foremost importer of Goupil-style artists in the USA. The Knoedler data set differs substantially from that of Goupil’s in that the gallery’s high-end market was nearly exclusively a secondary market. Knoedler also traded in a much greater variety of artists. Most importantly, the gallery did business for a much longer period than Goupil. With the Knoedler data one can trace the evolution in the contemporary painting market from the 1870s through the 1960s.

Until the end of the 1880s, sales of contemporary painters took up most of Knoedler’s premium market. Table 4 uses the same three categories at the Goupil table (Table 2). However, with the passage of time, the demographics of the three categories change (Helmreich, 2020). Initially, contemporary art meant Goupil-style artists. For Knoedler, the change to what we now consider modern artists did not occur in substance until after the First World War. Similarly, for Knoedler, the Near Contemporary category before the war was primarily represented by the Barbizon painters, artists like Camille Corot, Charles Daubigny, Jean-François Millet, and Théodore Rousseau, among others. The demand for such pictures by anglophone collectors also encouraged an international market for younger French and Dutch artists who worked in the same pastoral vein and provided the same idealized representations of rural life. Thus, the percentage of sales devoted to paintings by Near Contemporary artists (a category then dominated by Barbizon painters) make steady inroads in Knoedler’s premium market for the next several decades, from a little under 6% of their total sales during the 1880s to about 14.5% in the 1890s to about 24.5% during the first decade of the twentieth century (see Table 5).

The gradual supplanting of Goupil-style artists with Barbizon artists is indicative of how much the patronage of the superrich affected the financial success of contemporary artists selling out of Parisian commercial galleries. As we’ve seen, until near the end of the 1890s the contemporary Parisian art market was closely tied to the anglophone collectors in London and New York, assisted by international-oriented dealers and other art agents, such as the American Art Association and its prestigious, high-end auctions (Ott, 2008). Comparing Tables 2 and 4, it is evident how much Knoedler’s distribution of premium sales between “Contemporary” and “Near Contemporary” closely paralleled Goupil’s. When, however, Knoedler (and other American dealers) decided to enter the Old Master market, London would increasingly replace Paris as the gallery’s primary trading partner for the American market (Santori, 2006). The effect on the contemporary art market was dramatic.

Knoedler’s move toward the Old Master market was motivated in part by the fact that its clientele receptive to both Goupil-style artists and Barbizon-style pastoral painting had grown old, died, or moved on to other collecting interests. The difference in Knoedler’s high-end clientele and what they bought before and after 1900 is striking. The fashionable Goupil artists of the 1860s and 1870s had similarly aged. Many of these artists had fallen out of fashion. We can see these changes in the demography of Knoedler’s core collectors. Before 1900, Knoedler sold at least as many as twenty paintings to sixty-three different collectors. Of these, only three, William Clark, Henry Clay Frick, and Andrew Mellon, moved from collecting Goupil-style and pastoral paintings to Old Master art.Footnote 20 Fewer collectors also bought in volume from Knoedler between 1900 and 1914 (22). Moreover, the great majority of Knoedler’s post-1900 collectors had little interest in contemporary art. John Quinn, an avid collector of modernist art, noted in a letter to the French dealer Paul Rosenberg in 1922 that “The old houses on the street [5th avenue], like Knoedler’s or Gimpel & Wildenstein or Durand-Ruel have clients who are not educated up to Picasso. The salesmen in the place do not believe in modern art.”Footnote 21 Knoedler’s premium sales of contemporary art (see Tables 5, 6) declined steadily with each passing decade, while Old Master painting sales increasingly dominated not just their premium sales, but their overall sales, from a little under 12% in the first decade of the twentieth century to almost half of their sales during the 1920s. The other obvious motivation for Knoedler to enter the Old Master market was that the profits from premium sales could be much greater than they experienced selling contemporary art.

Weakening sales for contemporary art was first most strongly expressed in the most expensive brackets, but gradually spread to the lowest regions of Knoedler’s premium market. Not until the 1950s did Knoedler’s premium sales of contemporary paintings edge slightly upward. Even then, such painting did not compete with the upper echelons of Knoedler’s Old Masters sales. Living artists who commanded premium prices for their work also declined rapidly in number after 1900. Tables 7 and 8 list by decade the number of artists whose paintings were sold by Goupil and Knoedler for premium prices and the percentage of those artists who were alive at the time of the sale. In the 1870s, Goupil sold works by 215 different living artists at a premium price. This number declined only slightly through the end of the century. Picking up this trend with Knoedler’s post-1900 sales, the proportion of contemporary artists’ work selling for premium prices compared to Near Contemporary and Old Master artists fell even more dramatically. As Old Master and Near Contemporary painting increasingly dominated Knoedler’s high-end sales after 1900, the number of living artists who participated in this premium market collapsed, from 74% in the 1890s to 11% by the 1920s, falling even further over the next several decades.

The artists that made up Near Contemporary painting purchased by the superrich changed after the First World War. Before the war, only Manet and Degas among the artists we consider modern had begun to penetrate the high-end American market. After the war, Barbizon painting commanded less interest from anglophone collectors. High-end sales of Corot and Millet paintings were joined by paintings by the core Impressionists and some Post-Impressionists (Renoir, Monet, Cézanne, Gauguin, van Gogh, and to a lesser extent Toulouse-Lautrec and Seurat). Between 1927, when Knoedler sold its first Cézanne painting to 1939, both Renoir’s and Cézanne’s sales prices averaged over $24,000. Notably, in both the USA and Europe important collectors of Old Master paintings during this period were also buying these Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists, without in general showing significant interest in the works by contemporary artists. This concentration on what I have elsewhere termed “classic French modern” art was remarkably restricted (Jensen, 2015). During the 1930s, for example, fifty-four of ninety-four (53.2%) Near Contemporary paintings Knoedler sold were created by either Degas, Monet, or Renoir.

5 Comparing contemporary artists’ market fortunes

How reflective of contemporary art prices between 1900 and 1960 is the Knoedler data? To attempt to answer this question we can turn to some specific examples that describe the declining fortunes of contemporary artists. In March 1914, an auction of the collection of an art investment consortium known as La Peau de l’Ours (The Skin of the Bear) signaled market recognition for some young and younger contemporary artists (Fitzgerald, 1995). Picasso’s “Family of Clowns” [Les Saltimbanques] reportedly sold for the highest price at 11,600 francs.Footnote 22 Another Picasso gouache sold for 5200 fr. Both sales would be considered low tier sales if represented on the Goupil/Knoedler tables. Picasso’s other four oil paintings in this auction sold on average for just over 1000 fr. each ($193); none reached a premium price. Only one Matisse painting sold at a premium, at 5000 fr. Altogether, Matisse’s ten paintings brought 15,581 fr., an average of 1558 fr., well below Goupil/Knoedler premium price level. Picasso and Matisse were unquestionably the Meissonier and Gérôme of their day: over 40% of the 88 paintings by all the artists in the sale sold for 300 fr. or less. Three of four paintings by André Derain went for less than 300 fr. or less. A fourth brought only 420 fr. (Tables 9, 10).

The highest prices went to paintings by only four artists: Picasso, Matisse, and the Near Contemporary artists: van Gogh and Gauguin, who were represented by one painting each. The Picassos belonged exclusively to the artist’s most accessible work, the Rose Period or earlier, in other words, before his foray into Cubism. This sale then was not entirely a market triumph for living artists. Of the younger artists working in Paris before 1914, only Picasso and Matisse can be said to have broken through to something approaching the high-end market. Even so, their full market validation indexed by prices would have to wait much longer. Consider that the average sales price for one of Meissonier’s paintings went from $3316 (17,575 fr.) in the 1860s to $7061 (37,423 fr.) in the 1870s to $9827 (52,083 fr.) in the 1880s. Table 9 compares Meissonier’s total sales and averages adjusted for CPI as relative worth for the 1920s through the 1950s compared to Knoedler’s sales of Picasso’s work over the same decades. Even as late as the 1950s, Picasso sales at Knoedler failed to match the CPI adjusted sales that Meissonier experienced during the 1880s.

We do not have to use the most successful painters to demonstrate the financial advantage of Goupil artists over later modernists. The pastoral peasant painter, Jules Breton averaged $1064 (5639 fr.) in sales at Goupil’s in the 1860s; $2486 (13,176 fr.) in the 1870s; and $4596 (24,359 fr.) in the 1880s. In the 1870s alone, Breton sold to the Goupil gallery eleven paintings for more than 12,000 fr. each and the gallery sold one of these for 40,000 fr.Footnote 23 Adjust Breton’s total sales and averages from the 1880s for relative dollars in the 1920s through the 1950s and he still compares very favorably against two of the most important French painters of the twentieth century who works were featured by Knoedler (Table 10), Matisse and Pierre Bonnard. Matisse surpassed Breton’s sales during the final four years of the artist’s life. Bonnard’s sales exceed Breton’s sales only after his death in 1944.

Another way to test the Knoedler data is to look at the documented purchases by Picasso and Matisse’s dealers. We know that Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler paid Picasso a total of 43,788 fr. ($8460) for all the work the artist made during the period from October 1913 to June 1914 (Fitzgerald, 1995). By comparison, Goupil sold a single Meissonier painting for more than 45,000 fr. ten times; Knoedler performed this feat twelve times. Similarly, Goupil sold a Gérôme painting eight times for more than this sum; Knoedler made ten such sales. Three times Goupil sold a Bouguereau for more than this; Knoedler did it six times. Breton sales via Goupil surpassed Picasso’s income from Kahnweiler in single purchases three times (once for 120,000 fr. or $25,657) and twelve times via Knoedler.

After the war, Paul Rosenberg, Picasso’s new dealer, aggressively sought to stimulate demand in the American market, arranging, for example, in 1923 a New York exhibition at the Wildenstein gallery that featured mainly the artist’s Neo-Classical paintings from the early 1920s (Fitzgerald, 1995). The advertised sales prices ranged from $1500 for a pastel to $6500 for the largest paintings. Picasso reportedly received from Rosenberg about 7500 fr. in 1921 for size #50 paintings, or about $560. In 1923 that sum rose to 17,000 fr. or $1037. Yet some of Picasso’s most remarkable (and largest) paintings sold for surprisingly low sums during this period. The French collector Jacques Doucet bought from Picasso Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (Museum of Modern Art, NY), subsequently one of Picasso’s most celebrated paintings, for either 20,000 fr. or 30,000 fr. ($1564) in 1924. Rosenberg bought from the artist The Three Musicians (Philadelphia Museum of Art) also in 1924 for 30,000 fr. In 1925, Picasso’s sales price to Rosenberg rose to 19,000 fr., but the falling franc against the dollar meant that on the international market his paintings had decreased in value, down to $904 for a #50 size painting. The stock market crash and the ensuing Great Depression generally continued to send Picasso’s prices downward. The most notable exception was Chester Dale’s acquisition of Les Saltimbanques in 1931 for the considerable price of $20,000. Knoedler managed to acquire and sell only three Picasso paintings during the 1920s at an average price of $4901. From 1930 to 1945, Picasso’s average prices at Knoedler across thirty-five paintings sold was $2622. Picasso’s most expensive picture at Knoedler from the 1920s to 1945 went for $14,000.

Matisse’s first contract with his gallery Bernheim-Jeune dates from 1909 (Dauberville, 1996). At the time, Matisse agreed to sell to the gallery a maximum-sized painting (commercial French canvases sized #50 had 116 cm. as its largest dimension), for 1875 fr. ($362). His next contract in 1912 retained the same rate, while the franc fell very slightly against the dollar. In the third contract, signed in 1917, the agreed price for a #50 canvas was raised to 4500 fr. ($778). The next contract signed in 1920 set the price for a #50 painting as 7000 fr. ($492). As the value of the franc against the dollar sharply declined, an American buying a Matisse painting would likely spend a third less than three years earlier. In his final 1923 contract with the gallery, Matisse agreed to sell a #50 sized painting for 11,000 fr. ($671). When the contract terminated in 1926, 11,000 fr. would have brought only $358. Matisse may not have felt the effects of these falling exchange rates inside France, but from the perspective of the international art market, his paintings were less expensive objects in 1926 than they had been in 1909. Only when Matisse signed a contract with Rosenberg much later, in 1936, did his prices recover from this decline and only marginally. The dealer agreed to buy a #50 painting for 30,000 fr. or $1821. Knoedler only managed to obtain fifteen Matisse paintings during the 1920s, with an average sales price of $4574. Between 1930 and 1945, Knoedler sold twenty-four paintings by Matisse at an average of only $2558. In all the years before 1946, Knoedler’s most expensive sale of a Matisse went for $13,500. Of importance too is how few contemporary artists are represented in Knoedler’s high-end sales. Of the sixty high-end contemporary paintings Knoedler sold during the 1930s, thirty-eight of them (63.3%) were painted by Derain, Matisse, and Picasso. The dominance of a few artists in Knoedler’s high-end market persisted through the 1940s.

6 Old Masters versus contemporary artists

Behind every news report today about another sensational sale price realized for a work by a contemporary or near contemporary artist is likely the unexpressed surprise that such recent work could command prices expected for Old Master art. It was not always this way; Old Master art was not always considered to be intrinsically of higher value than contemporary and near contemporary art. At the end of the nineteenth century, despite a handful of remarkable sales for Old Masters, prices for contemporary art generally kept pace with or even surpassed Old Master art, especially considered in the aggregate.

There are several famous instances where extremely high prices were paid for Old Master works during the nineteenth century. In 1852 the French state was drawn into a bidding war with London’s National Gallery and the Emperor of Russia for Murillo’s Immaculate conception (Prado, Madrid), and paid the unprecedented price at auction of £24,600 for the painting (Spaenjeers et al., 2015). Later in the century, the National Gallery paid the remarkable price of £70,000 for Raphael’s Ansidei Madonna. Yet these were very uncharacteristic prices for either artists’ work or for Old Master painting in general over the entirety of the century. Prior to the Raphael purchase, the most the National Gallery had ever spent on a painting was £7000 to acquire in 1880 Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin on the Rocks. The highest price for a contemporary artwork in a London auction during the decade of the 1880s was for a Meissonier at £6090.

The limitations of high-end Old Master auction prices during this era are perhaps best exemplified by the Demidov sale held in Florence in 1880.Footnote 24 The Demidov family were Russian aristocrats who had taken up permanent residence at their estate at San Donato. They were famous art collectors. They were also not averse to periodically selling off parts of their collection, of which the 1880 auction was the last major sale.Footnote 25 We can probably date the American taste for expensive Old Master paintings from this auction. William Vanderbilt was a highly visible buyer. Other participants included the Baron de Rothschild, numerous French, American, and British dealers, and even an agent for the Emperor of Russia. Vanderbilt came away with a Jean-Baptiste Greuze genre scene and a Solomon van Ruysdael landscape. Another American, Stanton Blake, purchased several paintings that eventually came to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Among the notable works on sale were Vermeer’s The Geographer (Städel Museum, Frankfurt), which sold for $4400, a Rubens landscape at $5800 (Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna), and one version of Rembrandt’s Lucretia at $29,200 (National Gallery, Washington). As is typical of art auctions, exceptional sales represented a minority. Of the recorded prices, just under 75% of the works in the auction were not high-end sales. Despite the contemporary prestige of the Demidov collection, some of the highest selling paintings that can be identified are now considered misattributions or works by less prestigious artists. Notably, the highest price, $42,000 (220,249 fr.), went for an unidentifiable seventeenth-century landscape by Meindert Hobbema. Other high prices were paid for an unidentifiable seventeenth-century genre scene presumed to be by Nicolaes Maes, a Rembrandt portrait now considered to be a seventeenth-century copy, an unidentifiable van Dyck portrait of Lady Cavandish, one of multiple possible versions of this model. Prestigious provenances did not necessarily guarantee the authenticity of works upon which enormous sums of money were spent. If we consider that art history was still in its disciplinary infancy, and the amount of serious art historical research was still very limited, the investment risk in Old Master paintings was much higher then. Perhaps this is an important reason why contemporary painting remained competitively priced with Old Master painting to the end of the century.

Few living artists’ works matched some of the prices at the Demidov sale, but Goupil sold a Meissonier in 1890 to the department store magnate, Alfred Chauchard, for 250,000 fr. The same year Chauchard paid 800,000 fr. to the American dealer James Sutton for the recently deceased Jean-François Millet’s L’Angelus and 850,000 fr. ($162,605) to a third dealer for Meissonier’s 1814, La Campagne de France (Musée d’Orsay, Paris), the highest price paid for a living artist’s work during the nineteenth century. Nationalism was clearly a major motivator for Chauchard’s purchases. He was also one of the few French collectors to compete with American and British collectors at the highest reaches of the art market.

Another sign of the lasting competitiveness of contemporary and near contemporary art with Old Master painting among collectors before the First World War can be seen in the 1910 New York auction results for the Charles Yerkes collection. Yerkes make his money in urban rail systems both in Chicago where he lived for many years and in the development of the London metro system. He was notoriously corrupt, having spent some months in jail, only to gain his release through extorting politicians. Late in life, Yerkes became an avid art collector. He was a major client of Knoedler, from whom he bought many of his modern paintings. Yerkes also purchased Old Master paintings from other American and English dealers. Of the more than 190 paintings, a surviving auction catalog provides hand-written sales prices for 77 nineteenth-century paintings and 120 Old Master works at the auction.Footnote 26 The nineteenth-century paintings totaled $1,096,600 at an average of $14,242. The Old Master paintings sold for $803,400 at an average of $6695. Eight of the top ten highest selling paintings in the collection were nineteenth-century works. The two exceptions were a presumed Rembrandt Portrait of a Rabbi, which sold for $51,100 and a Hobbema landscape A View in Westphalia, which went for $48,000. Both pictures have disappeared into private collections.

Yerkes had the best advice a Chicago collector could have during this period. He was advised by Sarah Tyson Hallowell, a pioneering curator of modern painting in Chicago and a major organizer of the Fine Arts Pavilion at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Hallowell also was a friend and advisor to Mrs. Potter Palmer and an art advisor to the Art Institute of Chicago. Yet many of Yerkes’ Old Master works were either of doubtful attribution or were uninspired examples of a particular artist’s work. Among the falsely attributed works were a “Raising of Lazarus” attributed to Rembrandt, a portrait of “Hans Gunder of Nuremberg” attributed to Dürer, a painting of a fool, attributed to Holbein, and a “Virgin and Child Enthroned with John the Baptist,” attributed to Memling. Yerkes did hit on some paintings. A Rembrandt, Philemon and Baucis, sold for $32,000 and is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. A second Rembrandt, Joris de Caulerij, sold for $34,500 (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco). But of the five most expensive paintings in the sale, three were by Camille Corot (d. 1875): Environs of Ville d’Avray ($201,000), The Fisherman ($80,500), and Morning ($52,100), all now likely in private collections. The second most expensive painting was J.M.W. Turner’s Rockets and Blue Lights at $129,000 (The Clark, Williamstown, Ma.).

Yerkes’ foray into Old Master collecting was symptomatic of a general transformation in the market for Old Master art that was driven by American collectors (Santori, 2006). J.P. Morgan was perhaps the most influential collector in the world at the end of the century. In 1896 Morgan surpassed London’s National Gallery 1885 Raphael acquisition when he acquired his own Raphael (Colonna Madonna, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY) for 2,523,329 francs or £100,000. Morgan bought a second Raphael, St. Anthony of Padua, in 1901 for another £100,000. These two purchases spearheaded a flood of American acquisitions of Old Master painting that far exceeded prices paid for comparable paintings at English auctions.Footnote 27 The impact this trend driven by Americana collectors had on the contemporary art market was dramatic.

Morgan never had much interest in modern painting. Henry Clay Frick’s first purchases, on the other hand, were paintings by such living artists as Bouguereau, Breton, Cazin, and Gérôme. He then discovered the pastoral landscape painters, some of whose paintings he continued to buy long after entering the Old Master market. Benjamin Altman also began collecting with purchases of some modern American paintings and Goupil-style artists. Many of these pictures Altman later sold off via Knoedler, keeping only some Barbizon-style paintings, while avidly buying Asian ceramics and Old Master paintings (Haskell, 1970).Footnote 28 Altman subsequently spent a recorded $5,730,986 on his Old Master paintings between his first acquisition in 1905 and his death in 1913.Footnote 29 He bought Old Master paintings at an astonishing average of $163,742. In 2018 dollars adjusted for CPI this would be at least equivalent to more than $4 million per picture and more than $20 million using other metrics. A third great collector of the era, Henry Havemeyer, similarly began collecting Goupil-style artists, before discovering the Old Masters. In 1889, he was among the very first American collectors to buy Rembrandt paintings at high prices. Through his wife Louisine’s friendship with Mary Cassatt, the Havemeyers were also among the earliest collectors of works by the core Impressionists, as well as Manet, Courbet, Daumier, and Ingres. The Havemeyers’ interest in French modern art set them apart from collectors like Morgan, Altman, and Frick, although Frick did buy some modern pictures just before the First World War.

The intense interest in Old Master art by American collectors caused a growing disparity in prices between contemporary artists and most near contemporary artists and the Old Masters that persisted into the interwar years. Looking briefly at Knoedler’s Old Master sales, first between 1918 and 1929 and then from 1930 to 1945, the chasm between Old Master and contemporary art prices is obvious. During the late teens and twenties, Knoedler sold 490 paintings for $5000 or more, about 50% of their overall sales of Old Master works. The average sales price for all 982 Old Master paintings sold during these years was $21,175. Their highest sales price was for a Holbein portrait, which they sold to Andrew Mellon for $864,000. They sold an additional forty-six paintings during this period for $100,000 or more. During the Depression and war years, Knoedler sold sixteen paintings for $100,000 or more, with their greatest sale being a Piero della Francesca sold for $400,000 to the Frick Collection.

After the Second World War, the prices for Matisse and Picasso’s works gradually began to catch up with Old Master art. By this time, both artists were old men. Matisse died in 1954 and Picasso was in his seventies during the 1950s. The average price for a Matisse painting at Knoedler between 1946 and 1960 was $13,984. The gallery’s highest sale went for $60,000 (twice). Picasso’s average price at Knoedler was $21,727 with a high price of $125,000, which was almost twice as much as any other Picasso Knoedler sold in these years. Meanwhile, Knoedler’s Old Master sales price average was $21,359, with two sales for $400,000 (for a Raphael and a Holbein) and twenty-two sales for $100,000 or more.

Some brief examples may demonstrate just how much the market for contemporary art changed beginning in the 1960s. In 1947 Betty Parsons, the dealer for the Abstract Expressionist painter Mark Rothko, sold the artist’s paintings for between $300 and $500 (Breslin, 1998). In 1951, Rothko’s highest recorded selling price was $3000. By 1967, however, a Rothko painting sold for $26,000 and by 1969 they were selling for as much as $40,000. After Rothko’s death in 1970, the prices for his work continued to rise. In 2012 Rothko’s Orange, red, yellow (1961) sold at auction for $88.9 million, still the record price for the artist’s work (Villa, 2021). Other landmarks in the recent market: in 1983, Julian Schnabel’s paintings, according to his dealer Mary Boone, sold for between $25,000 and $60,000, which struck contemporary observers as being remarkably high for a 32-year-old artist (Hogrefe, 1983). In 1999 (Studer, 1999) a Big Electric Chair by Andy Warhol (d. 1987) was auctioned for 1.65 million pounds ($27 million). Then, in 2007 one of Jeff Koons’ Hanging Heart sculptures set a record auction price for a living artist at $23 million (Forbes Magazine, 2007). In 2019 another work by Koons, Rabbit, sold for over $91 million. In 2010, Jasper Johns’ Flag (1955), was reputedly sold in a private transaction for $110 million, which would be the current record for a living artist (Vogel, 2010).

7 Implications

This paper has relied heavily on the financial doings of just two commercial galleries. Many other galleries in Paris, London, and New York sold contemporary artists and Old Master artists. In other galleries, it is possible that contemporary artists did better with high-end sales than they did at Goupil’s and Knoedler’s. We cannot fully test the conclusions reflected in the Goupil/Knoedler sales data in the absence of comparable data sets from rival galleries. Until such time as other gallery stock books become available as data sets with unrestricted access, we are left to ponder whether Knoedler could have sold any contemporary artist’s paintings for higher prices if the gallery had had the opportunity and the vision to recognize the right artists to sell? Possibly. There are, however, reasons to think Knoedler was representative of the contemporary market over time. Although the gallery was slow to pursue Impressionist and Post-Impressionist pictures, in the 1920s they became very active in this market. Similarly, they got into the market for Picasso and Matisse late, yet the gallery’s commitment to these artists steadily increased over the years. It also seems safe to conclude that no other contemporary artists sold for higher prices than Matisse and Picasso did prior to the 1960s.

Despite the limited perimeters of this research, the data presented confirms that contemporary artists from the 1870s to the 1890s could earn incomes greater, often much greater, than those of the next several generations of artists. It is also evident that more artists were able to take advantage of these economic opportunities than they would later. The data underlines the importance of an international market for art, a market that was distinctively different than what is reflected in regional auction data. Dealers and artists who could command an international clientele did better in the short-term than those who could not—and this was a lesson learned early in the history of modern commercial galleries.

Further, the data illustrates the largely unnoticed impact the international market for Old Master painting had on the market for contemporary art. It is reasonable to assume that contemporary artists did so well during the 1870s–1890s because of the investment in their work by extremely wealthy, largely anglophone collectors. Once the next generation of very wealthy anglophone collectors were drawn into the Old Master art market, the collecting of contemporary art fell to significantly fewer wealthy individuals. In general, very wealthy American collectors appear to have been uninterested in buying adventurous contemporary art until the 1960s. They were, however, willing to pay high prices for “classic French modern” paintings. The willingness (or its absence) by the superrich to spend on contemporary art establishes the two arcs in the contemporary art market over the last century and a half. A curious but unprovable connection exists between the U-shaped character of the contemporary art market and a similar U-shape in income inequality over the same period (Alvaredo et al., 2013).

Notes

For an important exception see Baetens (2010).

See, for example, Watson (1992). Watson narrative account, which covers much of the material presented in this essay, often obscures the relative successes of living artists in the art market of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

There are striking consistencies between the artists represented in certain British collections and those of their American counterparts. For example, the artists whose paintings are represented in the collection of the American-born, but British citizen Chester Beatty, donated to the National Gallery of Ireland, are also those found in the collection of the New York banker George Seney: Breton, Corot, Couture, Daubigny, Dupré, Fromentin, Gérôme, Mauve, Meissonier, Millet, Troyon, among numerous others. Seney’s collection was auctioned off in 1885 and 1891.

Some have argued that only a top thirty or so living artists benefit from today’s market, but I have seen no statistical evidence to support this claim. The global nature of the contemporary art market ensures that more artists should be benefiting from significant sales than fifty years ago. It is just difficult to establish how many.

Currency exchange rates, indexed against the gold standard, remained remarkably stable until the First World War. After 1914 this paper uses Edvinsson (2016). Edvinnson’s website calculates exchange rates on annual averages instead of day-to-day or monthly variations using as comparative metrics the price of gold, the price of silver, and the cost of labor.

See https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/provenance/search.html. The online data is available via GitHub: https://github.com/thegetty/provenance-index-csv. The Goupil data set has over 44,000 entries and Knoedler set has over 33,000 entries. Inevitably, the GRI data sets contain numerous duplicates, transcription errors, and errors of interpretation. The edited data that inform the paper’s tables have been posted to the Harvard Dataverse, V1. Jensen, R., 2022, “Goupil Premium Sales,” https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JUCOKE and “Knoedler Premium Sales,” https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/Y9BAZA.

Gilded Age American collectors, according to Ott (2008), were motivated to enter the art market “at its highest level of value” to differentiate “themselves from the merely well-off, who had to content themselves with second-tier commodities, like prints, drawings, or domestic paintings, and in less prestigious venues (137).”

Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor, 1898, 668 and 673.

The value of the franc declined, however, during this same period against the dollar.

See Carter (1892), who first establishes the fourteen hundred guinea metric to calculate the number of such sales at this price or above since 1885. The Art Journal subsequently used this standard annually to list by artist, painting title, and sales price, the pictures that passed this limit.

Rosen and Zerner (1976) described the function of the highly finished surface [fini] this way: “The function of the fini is ambiguous: it guarantees both the amount of work done and the quality of execution that ought not to show itself: it gives value to an object who physical properties it camouflages (33).”

The benchmarks for each decade are adjusted according to the CPI index using the middle year for each decade for comparison. Similarly, to simplify currency comparisons, in these tables the middle year of each decade is used when translating French francs and English pounds into dollars. However, the First World War de-stabilized the three economies in relation to each other, so post-1914 foreign currencies exchange rates into dollars are calculated annually.

Table 2 was constructed by listing only the artists for whom the dealer records suggest twenty or more direct purchases from the artist or by known intermediaries (gallery agents in other cities, especially the Hague). Thus, the gallery eventually acquired many more paintings by Camille Corot than are reflected in Table 2, because these purchases came on the secondary market.

Durand-Ruel’s orientation toward the auction houses is illustrated by his account of his extremely aggressive purchases at the Khalil-Bey auction in 1868. According to Durand-Ruel (2014), “We bid up, or had our friends bid up, all the paintings and in particular those we had sold, in order to demonstrate at [this] sensational sale that our wonderful school was climbing significantly in value and would soon rise more steeply (57–58).”

See, for example, the way that Durand-Ruel’s business practices are discussed in Patry et al. (2015).

An interesting biography of A.T. Stewart, which includes these price figures, was included in Brockett (1872).

William Clark’s collection was donated to the Corcoran Gallery, which in recent years has been absorbed by the National Gallery of Art. Frick created his own museum, while many of Mellon’s paintings are also now in the National Gallery. Though they were not regular customers of Knoedler’s, Collis and Arabella Huntington were also significant collectors of both Goupil artists and Old Masters.

Quinn to P. Rosenberg dated March 5, 1922, from Quinn’s letterbook, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. (1921–1922). 1921 August 29-1922 July 26. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/a2465760-d80e-0133-8daa-00505686a51c.

According to an annotated auction catalogue, the Munich dealer Heinrich Tannhäuser bought Les Saltimbanques (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) for 11,500 fr. ($2,221). The catalogue with hand-written notations listing the sales prices for each work in the auction can be found at https://bibliotheque-numerique.inha.fr/collection/item/21253-collection-de-la-peau-de-l-ours-vente-du-2-mars-1914.

The age of the artist of course also matters, Breton was in his late 40s, early 50s during the decade of the Seventies, while Picasso was in his early thirties at the time of the Peau de l’Ours auction.

Information about the auction’s participants and prices paid were widely followed in contemporary press reports. See “Prince Demidoff and the San Donato Sale,” The Art Amateur, 2 (April 1, 1880): 98–99.

A private sale from another member of the Demidov family to the Art Institute of Chicago created the museum’s formative collection of Old Master painting.

Catalogue deluxe of ancient and modern paintings belonging to the estate of the late Charles T. Yerkes (New York: American Art Association, 1910), in the holdings of the Frick Art Reference Library. The catalogue mysteriously placed Edwin Landseer with the Old Masters and I have counted Thomas Lawrence among nineteenth-century artists since the largest share of his career occurred during the first three decades of the nineteenth century.

Spaenjeers et al. (2015) lists the three top auction sales between the Murillo auction and 1914: £28,250 (Hals, 191); £29,500 (Mantegna, 1912) and £44,000 (Rembrandt, 1913). However, American collectors, buying directly from an owner or through dealer intermediaries, often paid higher than the very highest auction prices for their pictures. Benjamin Altman, for whom the Duveen Brothers purchased his Rembrandt in 1913, paid more than £44,000 in non-auction transactions for Old Master paintings at least nine other times. Henry Frick paid more for some of his pictures at least seven times prior to 1914.

According to Haskell Altman began his collecting career buying American paintings (presumably by living artists) but sold them. He also donated his Barbizon and Barbizon-style paintings to the Metropolitan. These ten paintings he had purchased during the 1890s for about $80,000 in total.

The Metropolitan Museum was able to document the purchase price for 44 of the 60 paintings Altman donated to the museum. This data may be found in the provenances provided by the Met at https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection. It is likely that Altman purchased the other sixteen paintings near or above the average price he paid for his other Old Master pictures.

References

Adler, M. (1985). Stardom and talent. The American Economic Review, 75(1), 208–212.

Alvaredo, F., Atkinson, A. B., Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2013). The top 1 percent in international and historical perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), 3–20.

Baetens, J. D. (2010). Vanguard economics, rearguard art: Gustave Coûteaux and the modernist myth of the dealer-critic system. Oxford Art Journal, 33(1), 25–41.

Baetens, J. D. (2020). Artist-dealer agreements and the nineteenth-century art market: The case of Gustave Coûteaux. Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2020.19.1.2

Breslin, J. E. B. (1998). Mark Rothko: A biography. University of Chicago Press.

Brockett, L. P. (1872). Men of our day; or biographical sketches of patriots, orators, statesmen, generals, reformers, financiers and merchants. Ziegler and McCurdy. Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor (September 1898). 3(18). Retrieved January 2022, from http://www.all-biographies.com/politicians/alexander_turney_stewart.htm

Carter, A. C. R. (1892). The art sales of 1892. The Art Journal, 54, 283–287.

Champarnaud, L. (2014). Prices for superstars can flatten out. Journal of Cultural Economics, 38(4), 369–384.

Dauberville, G. M. (1996). Matisse: Henri Matisse chez Bernheim Jeune. Editions Bernheim-Jeune.

David, G., Huemer, C., & Oosterlinck, K. (2020). Art dealers’ inventory strategy: The case of Goupil, Boussod & Valadon from 1860 to 1914. Business History. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2020.1832083

Durand-Ruel, P. (2014). Paul Durand-Ruel. Memoirs of the First Impressionist Art Dealer (1831–1922). Flammarion.

Edvinsson, R. (2016). Historical currency converter. Retrieved December–February 2022, from https://www.historicalstatistics.org/Currencyconverter.html

Fitzgerald, M. (1995). Making modernism. Picasso and the creation of the market for twenty century art. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Forbes Magazine (Nov. 21, 2007). Heart breaking record. Retrieved January 6, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/2007/11/21/collecting-art-auctions-forbeslife-cx_nw_1121koons.html?sh=3f4f055e3709

Haskell, F. (1970). The Benjamin Altman Bequest. Metropolitan Museum Journal, 3, 259–280.

Helmreich, A. (2020). The art market as a system. American Art, 34(3), 92–111.

Hobsbawm, E. (1989). The age of empire 1875–1914. Vintage Books.

Hogrefe, J. (May 20, 1983). Julian Schnabel’s crock of gold. Washington Post.

Jansen, L., Luijten, H., & Bakker, N. (Eds.) (2009). Vincent van Gogh—The letters. http://vangoghletters.org

Jensen, R. (2007). Measuring canons: Reflections on innovation and the 19th-century canon of European art. In Partisan canons (pp. 27–54). Duke University Press.

Jensen, R. (2015). Classic French modern. In Scripta manent. Schriften zur Sammlung «Am Römerholz» (Vol. 1, pp. 115–122). Hirmer Verlag.

Masson, F. (1893). Adolphe Goupil. The Art Journal, 31, 221–222.

Officer, L. H., & Williamson, S. H. (2022). Measures of worth. Retrieved January 2022, from https://www.measuringworth.com/explaining_measures_of_worth.php

Ott, J. (2008). How New York stole the luxury art market. Blockbuster auctions and bourgeois identity in gilded age America. Winterthur PortfolIo., 42(2–3), 133–158.

Patry, S., Robbins, A., et al. (2015). Inventing impressionism: Paul Durand-Ruel and the modern art market. National Gallery.

Penot, A. (2010). The Goupil et Cie Stockbooks: A lesson on gaining prosperity through networking. Getty Research Journal., 2, 177–182.

Penot, A. (2017). La Maison Goupil: Galerie d’art internationale au XIXe siècle. Mare & Martin.

Reitlinger, G. (1961). The economics of taste. The rise and fall of picture prices 1760–1960. Barrie & Rockliff.

Rosen, C., & Zerner, H. (1976). The revival of official art. The New York Review of Books, 23, 32–39.

Rosen, S. (1981). The economics of superstars. The American Economic Review, 71(5), 845–858.

Santori, F. (2006). The Melancholy of masterpieces: Old Master painting in America (1900–1914). 5 Continents Editions Sri.

Serafini, P. (Ed.). (2013). La Maison Goupil et L’Italie. Le succès des peintres italiens à Paris au temps de l’impressionnisme.

Serafini, P. (2016). Archives for the history of the French Art Market (1860–1920): The Dealers’ network. Getty Research Journal, 8, 109–134.

Spaenjeers, C., William, N., Goetzmann, W. N., & Mamonova, E. (2015). The economics of aesthetics and record prices for art since 1701. Explorations in Economic History, 57, 79–94.

Studer, M. (October 14, 1999). New buyers with new money buoy prices in the art market. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 10, 2022, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB939828275296068523

Tabarant, A. (1947). Manet et ses oeuvres. Gallimard.

Velthuis, O. (2005). Talking prices. Harvard University Press.

Villa, A. (September 29, 2021). The most expensive works by Mark Rothko sold at auction. Art News. Retrieved January 11, 2022, from https://www.artnews.com/list/art-news/artists/most-expensive-works-by-mark-rothko-auction-records-1234604959/untitled-1952

Vogel, C. (March 18, 2010). ‘Planting a Johns’ ‘Flag’ in a private collection. NY Times.

Watson, P. (1992). From Manet to Manhattan: The rise of the modern art market. Random House.

Weill, B. (2021). Pans! dans l’oeil!… ou trente ans dans les coulisses de la peinture contemporaine 1900–1930, 107. Archives Berthe Weill. Retrieved January 2022, from https://www.bertheweill.fr/pandansloeil

Williamson, S. H. (2022). Seven ways to compute the relative value of a U.S. dollar amount, 1790 to present. MeasuringWorth, Retrieved January 2022, from https://www.measuringworth.com/uscompare/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jensen, R. The rise and fall and rise again of the contemporary art market. J Cult Econ 47, 461–488 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-022-09458-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-022-09458-3