Abstract

The purpose of this study is to analyse the effects of personal demographic factors on Chinese university students’ values and perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) issues, and to identify the link between personal values and perceptions of CSR. The quantitative data consisted of 980 Chinese university students, and were collected by using a structured self-completion questionnaire. This study found that: 1) the importance of values education should be stressed, because we found that altruistic values associate negatively with perception of CSR, in contrast, egoistic values associate positively; 2) a CSR education programme should be designed accordingly to fit different student characteristics and needs such as gender and major differences; 3) values should be used as criteria for education and recruitment purposes, e.g., we found that female students represent more ethical values than male students, and have a more negative perception of the CSR performance; 4) the importance of environment performance should be recognised by Chinese corporations and policy-makers, because we found that Chinese corporations perform better in economic and social responsibilities than environmental responsibility. It provides an insight of the value structures of Chinese university students and the forces that shape ethical perceptions. It offers a comprehensive study of Chinese companies’ CSR performance, and the results improve the awareness of scholars and managers in solving the current problems and developing their CSR performances further.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ethics Education in China

China’s transition to a market economy has brought significant changes to Chinese society. China has achieved a great deal of success in its economic growth, but the transition has led to deterioration in the traditional morality of the Chinese people (Shafer et al. 2007). For example, the phenomenon of money-worship has grown, and unethical and irresponsible business practices have crept in (Liu 2002; Shafer et al. 2007). Teaching university students siness ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has become increasingly important for business scholars and executives in China in recent years.

The history of ethics education in China can be traced back to Confucius (551-479 BC), the core of Confucianism being to focus on secular ethics and morality, and educate people to cultivate the virtues. The overall goal of Confucian ethics education is to become a superior person and achieve harmony (Murphy and Wang 2006; Fan 2000; Wong et al. 1998).

The concept of ethics education in China has been further developed under particular social and culture changes, such as the modernization process, which is leading the changes in Chinese values and lifestyles (Qi and Tang 2004). The contemporary ethics education in China is an umbrella concept that consists of various educational programmes such as Communist ideology, politics, law, morality, and mental health (Zhu and Liu 2004). It regards “serving the people as the keystone, collectivism as a principle, love for the nation, people, work, science and socialism as basic requirements and social morality, professional ethics and family virtues as strength” (ME 2001). Ethics education has been carried out at all levels of educational institutions, from primary schools to national executive leadership academies (Bettignies and Tan 2007).

The major weakness of ethics education in China is in the emerging issues such as business ethics and CSR which have become central to 21st-century business. The importance of business ethics/CSR education has been recognised as it can raise students’ ethical awareness and change their ethical attitudes (Balotsky and Steingard 2006). Unfortunately, education in business ethics and CSR in Chinese educational institutions has lagged far behind the present urgent demands. According to Wu, in China less than one in thirty universities offer business ethics courses (Wu 2003). The Chinese universities are almost devoid of specified CSR courses, the only exceptions being some MBA programmes. Zhou et al. (2009) concludes that business ethics instruction in China is presently provided on a limited scale, and there are constraints (such as the overall social environment, teaching materials etc.) affect business ethics education in China.

Prior Studies on CSR and Motivations of the Study

The term CSR originates from the West and its adoption has a relatively short history spanning less than 20 years in China. Plenty of cross-cultural/national evidence indicates that the differences in the cultural and social backgrounds, as well as political and institutional environments result in the views on CSR taking different forms in different parts of the world (see, e.g., Shafer et al. 2007; Whitcomb et al. 1998). The North American concept of CSR represents the “original” context of the phenomenon by emphasising its philanthropic aspects (Matten and Moon 2004). Companies typically address issues of responsibility explicitly in corporate policies, programmes and strategies. In Europe and especially in the Scandinavian countries, however, the concept of CSR is more focused on actual company operations (Halme and Lovio 2004), and CSR issues are more implicit in the formal or informal institutional business environment and join the list of state duties and the legal context (Brønn and Vrioni 2001; Matten and Moon 2004). In the emerging countries such as China, CSR is still in its infancy, which is still about corporate operations at the basic legal level, and Chinese society is still struggling with issues such as corruption, labour rights, distributive justice, corporate crime, product safety and pollution (Tian 2006; Lu 2009). Previous cross-national studies found that Chinese subjects show much greater scepticism concerning the ethics and social responsibility in business success (Ahmed et al. 2003). Redfern and Crawford (2004) concluded that Chinese subjects are less idealistic, less concerned with humanitarianism, and more concerned with economic considerations such as profit than their Western counterparts.

Numerous international studies examine how business ethics and CSR issues and behaviours are affected by personal socio-demographic factors such as gender, age, education (for example, Fukukawa et al. 2007; Lam and Shi 2008; Ibrahim et al. 2008; Lan et al. 2008; O’Fallon and Butterfield 2005). Most studies focus on the role of values in enacting business ethics and CSR as values provide a broad framing structure in understanding individual choices and motivations for actions on the emergent business ethics and CSR issues (Mills et al. 2009; Carroll 1996). In China, however, individual-focused research on the effects of personal factors on business ethics/CSR issues, especially the relation to personal values, has been largely neglected. This study aims to fill in this gap between such studies in Chinese and international research taking gender, study major, and study year level as the personal factors, focusing on the effects of personal values on individual perceptions of CSR.

Chinese university students are the future leaders of China, whose current CSR awareness and opinions will anticipate their future behaviour on CSR issues which leads the development of CSR in China. We are trying to complete a study which provides information about Chinese university students’ values and perceptions of CSR issues, and investigates the effects of value on perceptions of CSR issues. This study contributes to the existing literature in two significant ways. First, this study examines Chinese university students’ personal values, linking them to the perception of CSR issues. Recent studies have found that beside being influenced by traditional Confucian values, the contemporary Chinese younger generation display a strong endorsement of emerging market values (Western values) (Xi et al. 2006; Lan et al. 2008). Thus, this study aims to provide a better understanding of the value structures of Chinese university students and the forces that shape ethical perceptions. The results can help educators to devise business ethics/CSR education programs targeting different student groups. The results can also help managers in employee recruitment and training. Furthermore, the study can help scholars to identify individual level motivators which enable them to better understand responsible behaviours and attitudes. Second, it offers a comprehensive study of Chinese companies’ CSR performance from the student point of view. This involves evaluation of a wide variety of CSR activities covering social, environmental, and economic dimensions. Since the studies concerning Chinese companies’ CSR performances have been largely neglected, the results provide important information for scholars to study the extent to which CSR has been accepted and interpreted in China, and improve the awareness of managers in solving the current problems and developing their CSR performances further.

Purpose of the Study

The main purpose of this study is to analyse the effects of personal demographic factors on Chinese university students’ values and perceptions of CSR issues, and to identify the link between personal values and perceptions of CSR. The theoretical aim of the study is to test the theory that values motivate individual attitudes and behaviours by studying their effects on individual perceptions of CSR. In particular, this article answers the following three research questions:

-

Q1.

What are the preferred values of Chinese university students? What are the differences between students from different disciplines, course levels, and gender?

-

Q2.

What are the perceptions of Chinese university students on Chinese corporate performance of their economic, environmental and social responsibility? What are the differences between students from different disciplines, course levels, and gender?

-

Q3.

How do personal values affect their perceptions of CSR performance?

Q1 and Q2 include the descriptions of the empirical phenomena of Chinese university students’ values and perceptions of CSR, and the comparisons of these descriptive phenomena between students from different demographical backgrounds. Q3 concerns explanation of phenomena based on hypothetical assumptions derived from theoretical constructs that values influence individual attitudes and behaviours.

The study has five parts. The theoretical background studies and hypotheses are discussed in the second part, emphasizing theories of values and CSR and suggesting eight hypotheses. The theoretical foundation of this study is that we believe perceptions of CSR are affected by values. The third part introduces the data and the quantitative research methods. The fourth part provides the findings. The last part of this paper draws the conclusions and offers some discussion.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Value as a Driver of Perception of CSR

In sociology, values are regarded as social phenomena and factors explaining human action. There is no universal definition of the concept of values (Lan et al. 2008). For example, Rokeach (1973) defined value as an enduring belief that a specific mode of conduct (instrumental values) or end-state of existence (terminal values) is personally or socially preferable to its opposite. According to Bengtson and Lovejoy (1973), values are conceptions of the desirable—self-sufficient ends which can be ordered and which serve as orientations to action. Dhar et al. (2008) divided the concept of values into micro and macro levels, “at the micro level of individual behaviour, values are motivating as internalized standards that reconcile a person’s needs with the demands of social life. At the macro level of cultural practices, values represent shared understandings that give meaning, order and integration to social living” (Dhar et al. 2008, p.183).

Over the last decade, Schwartz’s value theory has been the most widely accepted view (Siltaoja 2006). Schwartz and Bardi (2001) defined values as desirable, trans-situational goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in people's lives. Schwartz indentified 56 value items that can be grouped into ten value types, which can be further clustered into four value orientations: 1) self-transcendence (the altruistic value types of universalism and benevolence), 2) self-enhancement (egoistic values focused on personal power and achievement), 3) openness (including the value types of self-direction, hedonism and stimulation), and 4) conservation (including the tradition, conformity and security value types) (Schwartz 1992, 1994).

People in different cultures have various value priorities (Schwartz 1994, 1999), which can influence their perception of reality and motivation for action (Allport 1961; Siltaoja 2006). Confucianism has been the backbone of the values of the Chinese, but the emerging market ethics have also changed their ethical decisions (Redfern and Crawford 2004; Whitcomb et al. 1998). Currently, Chinese value systems can be divided into the following three orientations: 1) Chinese traditional values, displaying high Confucian dynamism and high long-term orientation; 2) Western values, representing individualism and materialism; 3) A combination of Chinese traditional values and imported Western values, including communism and collectivism (Lan et al. 2009).

Since the Chinese values are so different from the westerns, we are interested in whether the Schwartz value scale, which developed mainly on the basis of western samples, can be applied and fitted to the value studies in China. In this study, we have adopted some of the Schwartz value items, trying to measure and follow his value orientation typology.

A theme emerging from the literature is that personal values affect human perception and behaviour because they contain a judgement element in which they formulate social norms and emotions about what is right, good or desirable (Hemingway 2005; Parashar et al. 2004). The following table exhibits some important value definitions which emphasize the function of value as motivations for behaviour, attitude, and action (Table 1).

According to the theories displayed in the table above, there appears to be a consensus that values have a significant impact on human attitudes and behaviour, and may be drivers and guiding principles for human behaviour and actions.

Accordingly, an individual's evaluation of CSR actions is influenced by values which influence the extent of an individual’s perceived CSR and is influenced by societal activities and norms or standards (Siltaoja 2006; Hemingway and Maclagan 2004). For example, “someone who values economic development above other social goals may be especially likely to accept information suggesting that environmental protection will compromise economic goals; someone who values the physical beauty of nature above other social objects may accept information that supports a belief that any environmental change is a dire threat to that value” (Stern and Dietz 1994, p.68).

However, much research on the relationship between personal values and business ethics/CSR focused more on the effect of the values of individual belief, commitment, decisions, judgements and evaluation of business ethics/CSR (e.g., Orpen 1987; Rashid and Ibrahim 2002; Barnett et al. 1998; Jones 1991; Hemingway and Maclagan 2004; Shafer et al. 2007; Hunt and Vitell 1991; Joyner et al. 2002). Few studies have been conducted on the effect of values on the perception of CSR performance. Thus the main theory to be tested in this study is the relationship between personal values and perception of CSR.

CSR

There is no universally accepted definition of CSR, and a lack of consensus on what CSR really is. Garriga and Melé (2004) defined four categories of CSR theories and related approaches: 1) instrumental theories that the corporation is seen as only an instrument for wealth creation. Friedman’s shareholder approach (Friedman 1962), the strategic CSR approach (e.g., Baron 2001; Prahalad and Hammond 2002), and the resource-based approach (e.g., McWilliams and Siegel 2001; Hart 1995) belong to this category; 2) political theories, which concern the political power of corporations in society. The corporate constitutionalism approach to CSR (Davis 1960) and Corporate Citizenship (as in Hemphill 2004; Matten and Crane 2005) are good examples of this group; 3) integrative theories whose emphasis is on the satisfaction of social demands, including the community obligation approach (Selznick 1957), the social obligation approach (Jones 1980; McGuire 1963), CSP (Sethi 1975; Wood 1991), and the stakeholder approach (Freeman 1984; Clarkson 1995); and 4) ethical theories, based on the ethical responsibilities of corporations to society, good examples being modern CSR paradigms (Hancock 2005; Pettit 2005), the normative approach (Smith 2003; Epstein 1987), CSR3 (Frederick 1992), and the stewardship approach (Donaldson 1990). Based on the studies by Carroll (1999) and McWilliams et al. (2006), the Table 2 shows the evolution of CSR concepts and introduces some representative definitions.

The modern era of CSR began in the 1950s, and Bowen, granted the appellation of the father of CSR, initially defined it and emphasized the social obligations of modern enterprises (Bowen 1953). In the 1960s, there has been a considerable growth in the definition through attempts to conceptualize CSR. Scholars such as Friedman and McGuire have been the most important contributors in this period. For example, “The societal approach” suggested by McGuire (1963) defines companies as responsible to society as a whole.

The 1970s witnessed an acceleration in defining CSR. The definition of CSR became more specific and managerially involved (Carroll 1999). The most notable contributors in this period include Sethi, and Carroll. Carroll’s “pyramid of CSR” (Carroll 1979, 1991) was one of the most famous definitions of CSR. In the 1980s, the development of the CSR definition was focused on alternative or complementary concepts and notions such as stakeholder, CR, responsiveness, and business ethics (Carroll 2008). A significant example is the "stakeholder approach", which suggests that organizations are not only accountable to their shareholders, but should also balance the interests of their other stakeholders (Freeman 1984).

In the 1990s, the CSR concept served as the basis for developing alternative themes such as corporate citizenship, business ethics and sustainability. Scholars such as Wood, Carroll, and Elkington provided significant contributions in this period. The most famous CSR concept of this period was the “The triple bottom lines” proposed by Elkington (1998). Finally, in the most recent decade, the emphasis of the CSR concept has been transferred from theoretical contributions to empirical studies and practical implementation (Carroll 2008). Clearly, the core question has shifted from “what” to “how”. Notions such as NGO activism and strategic leadership have been extensively discussed. For example, Baron's concept (2001) placed CSR in a strategic business context and integrated it with marketing strategies.

In this study, our definition is based on the "Triple Bottom Lines" notion which divides CSR into three sectors: 1) Responsibility for financial success (profit); 2) Responsibility for the environment (the planet); and 3) Responsibility for society (people) (Elkington 1998). This concept means that corporate performance can and should be measured not just by the traditional economic bottom line, but also by social and environmental lines (Norman and Macdonald 2004). Our CSR measurements followed the "Triple Bottom Lines" principle, and we have developed measurable CSR items on three dimensions.

Clearly, CSR programmes or performances deal with various stakeholder concerns in multiple dimensions, and corporations are all faced with the same question of how to allocate their limited corporate resources to balance multidimensional performances. Three kinds of relationship have been discussed in previous studies: 1) a negative relationship between corporate social/environmental performance (CSP) and corporate financial/economic performance (CFP), because CSP may bring competitive disadvantage because of the additional costs it causes; 2) a neutral association; 3) a positive association between CSP and CFP, because the actual cost of CSP is minimal, the benefits potentially great, and high levels of CSP lead to lower explicit costs (Waddock and Graves 1997). Nevertheless, the third view has been the most commonly accepted (Waddock and Graves 1997; and Orlitzky et al. 2003). However, it is not clear whether or not Chinese corporations share the same view in relation to CSR performance, as no relevant empirical study has ever been done. This constitutes an incentive to evaluate Chinese corporations CSR in three dimensions and check if they are performed equally.

Hypotheses Based on Previous Research

There are great number of studies examining the relationship between values, ethical attitudes, and various personal socio-demographic factors, but the outcomes are mixed and no consensus has been achieved concerning the effect of these personal factors (Lam and Shi 2008). In our study, we select gender, study major, and study year level as the personal factors, and analyse the effect of these factors on personal values, and individual perceptions of CSR.

Previous studies suggest that altruistic values make a significant positive contribution to ethical behaviour, and are associated with higher levels of moral awareness. In contrast, egoistic values are more likely to be involved with unethical and irresponsible behaviour, and are associated with lower levels of moral awareness (see VanSandt 2003; Shafer et al. 2007). According to Finnegan (1994), individuals who embraced altruistic values more were more likely to perceive a given situation (or behaviour) as immoral. Thus, we suggest that:

-

H1: Chinese university students who embrace altruistic values more have a more negative perception of CSR performance.

-

H2: Chinese university students who embrace egoistic values more have a more positive perception of CSR performance.

O’Fallon and Butterfield (2005) have reviewed 174 empirical ethical decision-making publications from 1996 to 2003, concluding that often no difference is found between males and females, but when differences are found, females are more ethical than males. Arlow (1991), Deshpande (1997), and Ford and Richardson (1994) identified gender as a significant factor for ethical value and attitudes, while females were generally more ethical than males. According to Ruegger and King (1992), Ameen et al. (1996), Borkowski and Ugras (1998), Paul et al. (1997), Burton and Hegarty (1999), Okleshen and Hoyt (1996), Chonko and Hunt (1985), females were more sensitive to and less tolerant of unethical subjects than males. Based on those findings, we suggest that:

-

H3: Female students represent more ethical values than male students.

-

H4: Female students have a more negative perception of the CSR performance of Chinese corporations.

Recent empirical findings have suggested that the students’ major study was significantly affected by individual ethical values and attitudes (see Chonko and Hunt 1985; and Giacomino and Akers 1998). Borkowski and Ugras (1998) have reviewed 30 studies, identifying 6 studies which show that there is a significant difference between study major and ethical behaviour. According to Sankaran and Bui (2003), students from non-business majors tend to be more ethical than business majors. Hawkins and Cocanougher (1972) found that business majors were more tolerant in evaluating the ethics of business practices. Lindeman and Verkasalo (2005), found that students from business and technology majors display more individualistic and hard values such as power than other students. A et al. found that engineering and business majors view the current state of business ethics and corporate responsibility positively, whereas students from forest ecology and environmental science have more negative views. In another study, they found that the forest ecology and environmental science students have the most negative views on the forest industry's environmental and social responsibilities, while technology and business students have more positive views on the forest industry’s social responsibility in general (Amberla et al. 2011). Therefore, the fifth and sixth hypotheses of this study are:

-

H5: Ecology students represent more ethical values than business and technology students.

-

H6: Ecology students have a more negative perception of the CSR performance of Chinese corporations.

With regard to level of education, Sankaran and Bui (2003) have concluded that the older an individual becomes, the less ethical he or she is. The main explanation is that the older an individual becomes, the more he is involved in working positions and social relationships, and thus may make calculated ethical compromises to maintain relationships and business benefits. Wimalasiri et al. (1996) have found that there were significant differences in the investigation of individual ethicality among levels of education. With the increase in one’s life experience, there is a change in the awareness and interpretation of the social world and one’s place in it.

Empirical research by Tse and Au (1997), Borkowski and Ugras, (1992), and Terpstra et al. (1993) found that senior students were less ethical than junior students. One argument is that moral character is formed early in life, but may be changed by life experience such as education and work experience, and become more utilitarian (Tse and Au 1997). Borkowski and Ugras (1992) provided the comparable explanation that freshmen and juniors are more justice-oriented as a result of idealism, and experience from their employment makes seniors more utilitarian. In particular, Elias (2004) has found that younger students were more sensitive to CSR. Thus, we suggest that:

-

H7: Junior students represent more ethical values than senior students.

-

H8: Junior students have a more negative perception of the CSR performance of Chinese corporations.

Data and Research Method

The measurement of CSR performance has been complex and problematic because it concerns multidimensional measures (Waddock and Graves 1997). Waddock and Graves (1997) have discussed several measures in their study. For example, forced-choice survey instruments have limitations in returning rates and consistency of raters. The Fortune rating of CSP is more a measure of overall management than of CSP. The content analysis is subject to the comprehensiveness and purpose of the existing documents which might be biased. Social disclosure is a unidimensional measure. Most recently, several multidimensional measures have been applied in CSP studies, such as SOCRATES CSR screens which measure the degree of the institutional or promotional approach companies take to their CSR programs (Pirsch et al. 2007). The Ethical Investment Research Service (EIRIS) rating measures firm behaviour towards salient stakeholder groups (Brammer et al. 2006). Hartman et al. (2007) have introduced the three most often used rating systems for CSR in European corporations: the FTSE4-Good Index Series, the Dow Jones Sustainability Index EURO STOXX, and the Ethibel Sustainability Index.

The measurement used in this study to evaluate the perception of CSR performance was formulated on the basis of the current literature (e.g., Triple Bottom Lines) and the Sustainability Reporting Guideline (SRG), a globally applied framework for sustainability reporting (GRI 2006). Because the target of this study is not the published corporate reports but individual perceptions, the items formulated have to be easy to understand, and appropriate to the conditions of most respondents. Hence, we selected some items more suitable for the evaluation of common people’s perceptions, and adjusted them into a more understandable format so that respondents could comprehend them even without any specific knowledge of CSR. Another criterion is that these items should cover economic, social and environmental dimensions. The research instrument used to assess personal values has been formulated based on the Schwartz Values Questionnaire (SVQ) (Schwartz 1994), a widely-used scale for measuring personal values.

The study data consisted of university students at three Chinese universities, the final sample size of the study being 980 students: 400 from Nanjing Forestry University, 300 from Zhejiang University and 280 from Zhejiang University of Forestry and Agriculture. The survey response rate was 65%. The data were collected by using a structured self-completion questionnaire, while cross-sectional survey design and a stratified sampling method have been applied in collecting the data.

The questionnaire was pre-tested and independently back-translated between Chinese and English versions in order to ensure the accuracy and understandability of the information. The stratified sampling method applied ensured a relatively even distribution of samples between males and females, different majors, and course levels.

The survey was completed in May 2007, and the Chinese questionnaires were distributed to students completing engineering and technology, business and administration, and ecology majors. The distribution was carried out with the help of several contact persons from the universities who are either teachers or students working in the student union. The successful and efficient data collection has demonstrated the great benefit of utilizing "insiders" as distributors. One of our researchers participated in all the on-site distributions, and all of our contact people have been trained to be able to answer questions related to the questionnaire. Background information and definitions of the term "CSR" were also given on the questionnaire. The questionnaires were distributed to the students at the end of their classes (the selection of classes is mainly based on major and study year, we are trying to achieve an even distribution of samples), and our contact people collected them after 1 or 2 days, giving time for completion. On average, the questionnaire took about 20 min to complete.

The questionnaire has three parts. The first part asked for demographic information about gender, age, major, level, and knowledge of CSR. Student values and perceptions will be compared with these independent variables. The second part required information for intervening value variables which are used to enrich the understanding of student perception of CSR. The third part contains the core information of this study, dependent variables which consist of questions relating to the CSR performance of Chinese corporations and are used to evaluate student perception of CSR performance. The intervening and dependent variables contain 36 statements on a five-point Likert scale. One (1) represented a negative value, which means "entirely disagree" or "very poorly", and five (5) indicated a positive value, which means "entirely agree" or "excellent".

The study data has been analysed by a wide array of statistical analysis methods using the SPSS 17.0 and AMOS 17.0 statistical software. The basic descriptions of variables were determined by defining means and distributions. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) with varimax rotation factors were conducted in multivariable descriptions related to student values and perception of CSR performance. In factor analysis, KMO values over 0.5, p < 0.05, and a reliability coefficient Alpha over 0.7 are acceptable. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was employed to test the goodness of fit of the value measurement to the study data. Values of the GFI, CFI, NFI, TLI indices close to 1 are generally considered to indicate a good fit, RMSEA values less than 0.1 being considered a good fit also.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to run comparisons between student groups, value dimensions and their perception of the CSR implementation. The significance level used in the analysis was 5% (p < 0.05). K-means cluster analysis was conducted on group respondents based on the factor scores of their values. Combined variables were used to measure the perceptions of CSR performance, and cross-tabulations with χ 2 tests were used to examine the relationship between personal factors and perception of CSR performance, and between respondent value groups and their perceptions of the CSR performance (p < 0.05 being considered significant).

Results

Respondent Demographics

Table 3 shows the demographic profile of respondents. Of the 980 observations, 55.6% are male students. The average age of respondents is 21 years, but as the age differences between respondents are quite small, the age distribution is not shown on the table. The distribution of the respondents between five majors and four course levels is relatively even, except for a smaller number of students from the 4th year and above. This table also indicates that only a minority of respondents have work experience (13.3%). Another important finding here is that about half the respondents (47.9%) had no knowledge of CSR before this study was conducted. The mean of this variable is less than 2 (1.6), indicating that all the respondents have relatively poor knowledge of CSR issues.

Respondents’ Personal Values

The personal values of respondents were obtained by surveying the preferences for various values related to their personal objectives. Factor analysis was applied in determining the dimensions of these values. Both EFA and CFA methods have been applied in these value studies. First, half of the student sample has been randomly selected and their values have been analysed by EFA. A two-factor solution has been suggested, and it clearly fitted with the “altruistic” (factor 1) and “egoistic” (factor 2) categories of the Schwartz values scale. In the next, the other half of the samples has been analysed by CFA to confirm the two-factor model, the result appearing in Table 4.

According to the results in the Table 4, all the values positively indicate a good fit between the model and the observed data, which clearly supports the suggestion that the Schwartz values scale fits with the Chinese university student data in this study. Finally, the whole sample has been analysed by EFA, again this two-factor solution having been the optimal solution, and the reliability of the factor solutions being acceptable (α1 = 0.81 and α2 = 0.70).

Table 5 indicates that respondents represent higher altruistic values (the average mean of this value set being 4.3) than egoistic values (the average mean of this value set being 3.6). Comparisons of respondents from different backgrounds in their personal value dimensions were conducted by using one-way ANOVA. The results are listed in Table 6.

The results indicate that female students possess more altruistic values than male students, and male students demonstrate more egoistic values than female students, which clearly supports H3 “Female students represent more ethical values than male students.” The result shows that students majoring in business and technology emphasize the egoistic values more than students from an ecology major. According to the above results, ecology students display the least egoistic values, but the table also shows a conflicting result, indicating that ecology students display the least altruistic value. Thus H5 “Ecology students represent more ethical values than business and technology students.” has not been clearly confirmed. Another important finding is that students’ altruistic values gradually decrease as their course level increases, the first-year students displaying higher altruistic values than students from other years. Clearly, H7 “Junior students represent more ethical values than senior students” has been confirmed in this study.

Respondent’s Perception of CSR Performance

Respondents’ perception of CSR performance was assessed by their evaluation of thirteen corporate responsibility statements (which can be found in Table 9), covering issues concerning various responsibilities. An overall measure of the perception of CSR performance can be done by combining these thirteen variables into a single variable. In order to conduct further analysis, five categories of students were divided at four appropriate cut-off points: 1.8, 2.6, 3.4, and 4.2, which distributes the five-point Likert scale equally. The categories are called “entirely negative perceptions”, “slightly negative perceptions”, “neutral perceptions”, “slightly positive perceptions” and “entirely positive perceptions” (Table 7).

The mean of the single variable “perception of CSR performance” is 2.9, which indicates that respondents have a relatively neutral opinion on the CSR performance of corporations. According to Table 7, 27.1% of the respondents are on the negative side, while 21.9% are on the positive side, which indicates that respondents have more negative perceptions of the CSR performance of corporations. Cross-tabulations with χ 2 tests reveal the differences in perception that exist between distinct demographic categories of students (Table 8).

According to the table, the p value smaller than 0.01 indicates that there are significant differences in perception between distinct demographic categories of students. The results show that male students display more positive perceptions than female students, and female students represent more negative perceptions. These findings clearly support H4 “Female students have a more negative perception of CSR performance of Chinese corporations.” The results show that students majoring in forest ecology display the least positive perceptions. Thus H6 “Ecology students have a more negative perception of the CSR performance of Chinese corporations.” has been confirmed. Since there is no significant result found between students of different course levels, H8 “Junior students have a more negative perception of CSR performance of Chinese corporations” has not yet been confirmed in this study.

Further investigation of their perception of CSR performance was conducted by factor analysis and one-way ANOVA. Factor analysis was applied in determining the dimensions of perception of CSR performance (Table 9). The final solution of three factors is considered as the most appropriate, because they corresponded almost perfectly with the “triple bottom lines”, and the reliability of factor solutions is acceptable (α1 = 0.92, α2 = 0.79, and α3 = 0.52).

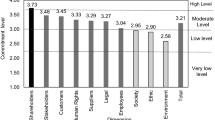

Three factors have been called "Environmental responsibilities" (factor 1), "Social responsibilities" (factor 2), and "Economic responsibilities" (factor 3). The table indicates that from the student’s point of view, Chinese corporations implement economic responsibility (mean = 3.4) and social responsibility (mean = 3.0) better than environmental responsibility (mean = 2.8). Comparisons of the perceptions of respondents from different backgrounds were conducted by using one-way ANOVA. The results are listed in the Table 10.

Significantly, male respondents display more positive perceptions of environmental responsibility than females, while female respondents have more positive perceptions of economic responsibility. Respondents majoring in ecology display the most negative perceptions on all the three CSR dimensions, which conforms perfectly to H6. In addition, the fourth-year students display the highest negative perceptions of social responsibility, but we found no clear results to support H8.

Relationship Between Values, and Perception of CSR Performance

K-means cluster analysis has been applied in this study to categorise the respondents according to their personal values. Factor scores from the "altruistic values" and "egoistic values" factors are used in the cluster analysis. A four-group clustering, called “mixed”, “egoistic”, “altruistic”, and “unconcerned” was found to be the most appropriate according to the F-test (Table 11).

According to the results of the factor analysis (Table 9), highlighted variables have been selected and combined into three summated variables, which are called “environment responsibility”, “social responsibility”, and “economic responsibility”. The same cut-off points, 1.8, 2.6, 3.4, and 4.2, have been applied to all the summated variables in order to classify respondents’ perceptions into five groups, which are called “entirely negative perceptions”, “slightly negative perceptions”, “neutral perceptions”, “slightly positive perceptions” and “entirely positive perceptions” (Tables 12).

The results of classifications of perception of CSR performance (in general and in three dimensions) and K-means clusters have been further investigated through cross-tabulations with χ 2 tests in order to study the relationship between the values of respondents and their perceptions of CSR performance (Table 12).

In general, the results suggest that respondents in the “altruistic” group display more negative perceptions of CSR performance than those in the “egoistic” group. Correspondingly, respondents in the “egoistic” group display more positive perceptions of CSR performance than those in the “altruistic” group. Similar results can be found on the environment, social and economic dimensions as well. These results clearly support H1 “Chinese university students who embrace altruistic values more have a more negative perception of CSR performance” and H2 “Chinese university students who embrace egoistic values more have a more positive perception of CSR performance.”

Conclusion

The effects of value on the perception of CSR performance has been recognised in this study. Accordingly, the importance of value in CSR education should be understood by educators, scholars and executives. Giacomino and Akers (1998) have suggested the following important effects that values impose on education.

First, discussion of the effects of values on behaviour can enhance the evaluation of ethical situations in the university. Since present-day students can be considered the leadership of tomorrow, their personal values are likely to affect corporate values in the future, and ethical decision-making in their professional life. Our results show that Chinese university students display strong preferences for higher ethical values, so that a corresponding increase in the business ethics may be expected in the future. As mentioned in the theoretical studies, emerging market values have changed their value structure, so that the value education should emphasise how to balance the conflict between collectivistic disciplines and individualistic freedom.

Second, developing more appreciated and consistent education programmes to meet the expectations of students occurs when educators are aware of the values of their students. For example, we find that the ethical values of university students decline during their education. One explanation is that they are more involved in the outside society and professional life during their time at university, which affects their value structures greatly. This result supports Sonnenfeld’s finding (1981) that those who are remote from the pressures of business display support more ethical and responsible behaviour, and their attitudes may change over time when they face the “real world”. Thus, the CSR education programme for senior students should emphasise the professional code of conducts, responsible leadership, public relations and responsibility, business ethics and moral discretion. CSR education in this period should focus on increasing the ability of students to recognize ethical issues (moral reasoning abilities) and cultivation of responsibility.

Based on our results, we argue that a CSR education programme should be designed accordingly to fit the characteristics of different majors. For example, our results found that ecology students have the most negative perceptions of the CSR performances of corporations, which may mean that they paid more attention to CSR issues and have better knowledge. The emphasis of further CSR education for ecology students should thus be more practical and specific, such as environmental standards, CSR assessments, certification and practical measurements of CSR. Since the results also found that business and technology students have the most positive perceptions of the CSR, we have to strengthen the CSR education for them, especially business students who will be the future executives of the companies setting the directions and policies of CSR. Thus the CSR education for them should focus on CSR strategies, communications, corporate values and culture, and the marketing implications of CSR performance. In summary, the results of this study are important for educators involved in teaching ethics, not only business ethics and CSR. Educators should apply diversified teaching methods and programmes which are based on student characteristics and needs, such as multimedia-based ethics training module (Geva 2010), ethics role-playing case method (Manuel 2010), or evidence-based administration (Junco and Perea 2008).

Third, values should be used as criteria for education and recruitment purposes. For instance, since female students represent more ethical values and more critical views of the CSR performance of contemporary Chinese corporations, recruiting and promoting women for top management positions are likely to strength the ethical base of the company. There is a clear implication that women are more suitable for decision-making in, and evaluation and monitoring of CSR issues. Companies currently use many psychology tests in their recruiting programme, but value evaluation is still weak. Thus development of value evaluation tools is needed. Continued staff training is a good tool to keep the commitment to ethics. Men especially should be more encouraged into ethics education.

An important finding for executives is that environmental responsibility is the weakness of Chinese companies’ CSR performance. We strongly recommend a theory provided by Russo and Fouts (1997, p.534), that “environmental performance and economic performance are positively linked and that industry growth moderates the relationship.” Chinese corporations should recognise the importance of environmental performance, and accept it as a positive driver for economic growth not a burden on profit-seeking. This finding also implies that the Chinese policy-makers should change their concentration from economic development to sustainability development in public policy decision-making. The concept of the “Construction of a Harmonious Society” is a good notion. However, the Chinese government should develop legislation and facilities to mandate and encourage CSR issues. For the purpose of improving environmentally responsible behaviour, educators should design education programmes that cultivate biospheric values such as unity with nature, a world of beauty, and the protection of nature.

A finding and a limitation of this study is that Chinese university students have relatively poor knowledge of CSR, and we believe that their knowledge level has greatly affected their perception of it. They may not understand the CSR concept well because they receive inappropriate and incorrect information, or have limited resources and experiences in creating the right perception. This may explain why we did not find perception differences among majors and course levels. However, this limitation has been partly circumvented in the questionnaire design process. In the measurement of CSR performance, we have selected and developed those CSR items which we believe everyone can understand and should have some experience of, even without any specific knowledge. According to the theory, there is no universally accepted definition of CSR, and a lack of consensus on what really CSR is, especially in China where CSR is an exotic concept with a short history. The findings of this study may display the correct picture that Chinese university students are ignorant of the concept of CSR because they miss proper CSR education. But this does not mean they are not concerned with current popular societal issues such as pollution, welfare, and employee relationships. We still can measure their CSR perceptions if the measurement equivalence has been carefully carried out. Further studies should extend this research to a larger sample size and measurement variables.

In addition, the seven value variables selected may not be sufficient to carry the value evaluation. This may also be why we got conflicting results regarding students’ values among different majors. However, the SVQ scale has passed the measurement invariance test in the Chinese sample. This may contribute to future value studies in China. Further studies should include more value variables, or even the whole SVQ. With developed measurements of values and CSR items, the relationship between values, perception of CSR, and demographic profiles may be surveyed better.

References

Ahmed, M. M., Chung, K. Y., & Eichenseher, J. W. (2003). Business students’ perception of ethics and moral judgment: a cross-cultural study. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(1), 89–102.

Allport, G. W. (1961). Pattern and growth in personality. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Amberla, T., Wang, L., Juslin, H., Panwar, R., Hansen, E., & Anderson, R. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility performance in the forest industries: A comparative analysis of student perceptions in Finland and the USA. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(3), 472–489.

Ameen, E. C., Guffey, D. M., & McMillan, J. J. (1996). Gender differences in determining the ethical sensitivity of future accounting professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(5), 591–597.

Arlow, P. (1991). Personal characteristics in college students evaluations of business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(1), 63–69.

Balotsky, E. R., & Steingard, D. S. (2006). How teaching business ethics makes a difference: findings from an ethical learning model. Journal of Business ethics Education, 3, 5–34.

Barnard, C. I. (1938). The functions of the executive. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Barnett, T., Bass, K., Brown, G., & Hebert, F. J. (1998). Ethical ideology and the ethical judgments of marketing professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(7), 715–723.

Baron, D. (2001). Private politics, corporate social responsibility and integrated strategy. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 10(1), 7–45.

Barry, V. (1979). Moral issues in business. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Bengtson, V. L., & Lovejoy, M. C. (1973). Values, personality, and social structure: an intergenerational analysis. American Behavioral Scientist, 16, 880–912.

Bettignies, H. C. D., & Tan, C. K. (2007). Values and management education in China. International Management Review, 3(1), 17–37.

Borkowski, S. C., & Ugras, Y. J. (1992). The ethical attitudes of students as a function of age, sex, and experience. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(12), 961–979.

Borkowski, S. C., & Ugras, Y. J. (1998). Business students and ethics: a meta-analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(11), 1117–1127.

Bowen, H. R. (1953). Social responsibility of the businessman (p. 6). New York: Harper & Row.

Brammer, S., Pavelin, S., & Porter, L. A. (2006). Corporate social performance and geographical diversification. Journal of Business Research, 59, 1025–1034.

Brønn, P. S., & Vrioni, A. B. (2001). Corporate social responsibility and cause –related marketing: an overview. International Journal of Advertising, 20(2), 207–222.

Burton, B. K., & Hegarty, W. H. (1999). Some determinants of student corporate social responsibility orientation. Business and Society, 38(2), 188–206.

Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) (1992). available at http://www.bsr.org/.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48.

Carroll, A. B. (1996). Business and society: Ethics and stakeholder management (3rd ed.). Cincinnati: South-Western College Publishing.

Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: evolution of a definitional construct. Business and Society, 38, 268–295.

Carroll, A. B. (2008). A history of corporate social responsibility: Concepts and practices. The Oxford handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, Chapter 2, Oxford University Press, (pp. 19–46).

CED (Committee for Economic Development) (1971). Social Responsibilities of Business Corporations. New York: Author.

Chonko, L. B., & Hunt, S. D. (1985). Ethics and marketing management: an empirical examination. Journal of Business Research, 13(4), 339–359.

Clarkson, M. (1995). The Toronto conference: reflections on stakeholder theory. Business & Society, 33(1), 82–131.

Costin, H. (1999). Strategies for quality improvement. Fort Worth, Texas: The Dryden Press.

Davis, K. (1960). Can business afford to ignore social responsibilities. California Management Review, 2(3), 70–76.

Deshpande, S. P. (1997). Managers’ perception of proper ethical conduct: the effect of sex, age, and level of education. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(1), 79–85.

Dhar, U., Parashar, S., & Tiwari, T. (2008). Profession and dietary habits as determinants of perceived and expected values: an empirical study. Journal of Human Values, 14(2), 181–190.

Donaldson, L. (1990). The ethereal hand: organizational economics and management theory. Academy of Management Review, 15, 369–381.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91.

Drucker, P. F. (1954). The practice of management. New York: Harper and Row Publishers.

Elias, R. Z. (2004). An examination of business students’ perception of corporate social responsibilities before and after bankruptcies. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(3), 267–281.

Elkington, J. (1998). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. New Society Publishers.

England, G. W. (1967). Personal value systems of American managers. Academy of Management Journal, 10(l), 53-68.

Epstein, E. M. (1987). The corporate social policy process: beyond business ethics, corporate responsibility, and corporate social responsiveness. California Management Review, 29(3), 99–114.

Fan, Y. (2000). A classification of Chinese culture. Cross Cultural Management – An International Journal, 7(2), 3–10.

Feather, N. (1988). From values to actions: recent application of expectancy-value model. Australian Journal of Psychology, 40(2), 105–124.

Feddersen, T., & Gilligan, T. (2001). Saints and markets: activists and the supply of credence goods. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 10, 149–171.

Finnegan, M. (1994). Ethics and economics. Master’s thesis, University College, Galway.

Fombrun, C. J., & Shanley, D. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 233–258.

Ford, R. C., & Richardson, W. D. (1994). Ethical decision making: a review of the empirical literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(3), 205–221.

Frederick, W. C. (1978). From CSR1 to CSR2: The maturing of business and society thought. Working Paper No. 279, Graduate School of Business: University of Pittsburgh.

Frederick, W. C. (1987). Theories of corporate social performance’. In S. P. Sethi & C. M. Flabe (Eds.), Business and society: Dimensions of conflict and cooperation (pp. 142–161). New York: Lexington Books.

Frederick, W. C. (1992). Anchoring values in nature: towards a theory of business values. Business Ethics Quarterly, 2(3), 283–304.

Frederick, W. C. (1998). Moving to CSR4. Business and Society, 37(1), 40–60.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder perspective. Boston: Pitman Publishing Inc.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine 13, September.

Fukukawa, K., Shafer, W. E., & Lee, G. M. (2007). Values and attitudes toward social and environmental accountability: a study of MBA students. Journal of Business Ethics, 71(4), 381–394.

Gandal, N., Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2005). Personal value priorities of economists. Human Relations, 58(10), 1227–1251.

Garriga, E., & Melé, D. (2004). Corporate social responsibility theories: mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics, 53(1–2), 51–71.

Geva, A. (2010). Ethical aspects of dual coding: implications for multimedia ethics training in business. Journal of Business Ethics Education, 7, 5–24.

Giacomino, D., & Akers, M. (1998). An examination of the differences between personal values and the value types of female and male accounting and non-accounting majors. Issues in Accounting Education, 13(3), 565–584.

Göbbels, M. (2002). Reframing corporate social responsibility: the contemporary conception of a fuzzy notion. Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam.

Greenfield, W. M. (2004). In the Name of Corporate Social Responsibility. Business Horizons, January–February, 19–28.

GRI (Global Reporting Initiatives) (2006). Sustainability Reporting Guidelines: G3, GRI. Amsterdam.

Halme, M., & Lovio, R. (2004). Yrityksen sosiaalinen vastuu globalisoituvassa taloudessa (Corporate social responsibility in the globalising economy). In E. Heiskanen (Ed.), Ympäristö ja liiketoiminta, arkiset käytännöt ja kriittiset kysymykset (pp. 281–290). Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Hancock, J. (2005). Introduction: Why this subject? Why this book?’. In J. Hancock (Ed.), Investing in corporate social responsibility: A guide to best practice, business planning and the UK’s leading companies (pp. 1–4). London: Kogan Page.

Hart, S. L. (1995). A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 986–1012.

Hartman, L. P., Rubin, R. S., & Dhanda, K. K. (2007). The communication of corporate social responsibility: United States and European Union multinational corporations. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 373–389.

Hawkins, D. I., & Cocanougher, A. B. (1972). Student evaluations of the ethics of marketing practices: the role of marketing education. The Journal of Marketing, 36(April), 61–64.

Heald, M. (1957). Management’s responsibility to society: the growth of an idea. The Business History Review, 31(4), 375–384.

Hemingway, C. A. (2005). The role of personal values in corporate social entrepreneurship. Research Paper Series, No. 31-2005, International Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility, Nottingham University Business School.

Hemingway, C. A., & Maclagan, P. W. (2004). Managers’ personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 50(1), 33–44.

Hemphill, T. A. (2004). Corporate citizenship: the case for a new corporate governance model. Business and Society Review, 109, 339–361.

Homer, P. M., & Kahle, L. R. (1988). A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 638–646.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1991). The general theory of marketing ethics: a revision and three questions. Journal of Macromarketing, 26(2), 143–153.

Ibrahim, N. A., Howard, D. P., & Angelidis, J. P. (2008). The relationship between religiousness and corporate social responsibility orientation: are there differences between business managers and students? Journal of Business Ethics, 78(1–2), 165–174.

Jamali, D., & Mirshak, R. (2007). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Theory and practice in a developing country context. Journal of Business Ethics, 72(3), 243–263.

Jennings, P., & Zandbergen, P. (1995). Ecologically sustainable organizations: an institutional approach. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 1015–1052.

Johnson, H. L. (1971). Business in contemporary society: framework and issues. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Jones, T. M. (1980). Corporate social responsibility revisited, redefined. California Management Review, 22(2), 59–67.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: an issue contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(April), 366–395.

Jones, T. M. (1995). Instrumental stakeholder theory: a synthesis of ethics and economics. Academy of Management Review, 20(2), 404–437.

Joyner, B. E., Payne, D., & Raiborn, C. A. (2002). Building values, business ethics and corporate social responsibility into the developing organization. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 7(1), 113–131.

Junco, J. G., & Perea, J. G. A. (2008). Evidence-based administration in the teaching of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics Education, 5, 35–58.

Lam, K. C., & Shi, G. C. (2008). Factors affecting ethical attitudes in Mainland China and Hong Kong. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(4), 463–479.

Lan, G., Gowing, M., McManhon, S., Rieger, F., & King, N. (2008). A study of the relationship between personal values and moral reasoning of undergraduate business students. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(1), 121–139.

Lan, G., Ma, Z. Z., Cao, J. A., & Zhang, H. (2009). A comparison of personal values of Chinese accounting practitioners and students. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 59–76.

Lindeman, M., & Verkasalo, M. (2005). Measuring values with the Short Schwartz’s value survey. Journal of Personality Assessment, 85(2), 170–178.

Lindfelt, L. L., & Törnroos, J. Å. (2006). Ethics and value creation in business research: comparing two approaches. European Journal of Marketing, 40(3/4), 328–351.

Liu, J. H. (2002). Philosophy and approaches to strengthen Corporate Social Responsibility in China. Conference on Labour Relations and Corporate Social Responsibility Under Globalization, Renmin University of China, Beijing, China.

Lu, X. H. (2009). A chinese perspective: business ethics in China now and in the future. Journal of Business ethics, 86(4), 451–461.

Manuel, T. (2010). An ethics role-playing case: stockholders versus stakeholders. Journal of Business Ethics Education, 7, 141–176.

Matten, D., & Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 166–179.

Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2004). Implicit and explicit CSR: A conceptual framework for understanding CSR in Europe. ICCSR Research Paper Series, No. 29.

McGuire, J. W. (1963). Business and society (p. 144). NJ: McGraw-Hill.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117–127.

McWilliams, A., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, P. M. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: strategic implications. Journal of Management Studies, 43(1), 1–18.

ME (2001). The Outline of Civic Moral Development. available at http://www.moe.gov.cn/edoas/website18/16/info3316.htm (in Chinese).

Meehan, J., Meehan, K., & Richards, A. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: the 3C-SR model. International Journal of Social Economics, 33(5/6), 386–398.

Mills, G. R., Austin, S. A., Thomson, D. S., & Devine-Wright, H. (2009). Applying a universal content and structure of values in construction management. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(4), 473–501.

Moser, M. R. (1986). A framework for analyzing corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 5(1), 69–72.

Murphy, B., & Wang, R. M. (2006). An evaluation of stakeholder relationship marketing in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 18(1), 7–18.

Norman, W., & MacDonald, C. (2004). Getting to the bottom of “triple bottom line”. Business Ethics Quarterly, 14(2), 243–262.

O’Fallon, M., & Butterfield, K. D. (2005). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 1996–2003. Journal of Business Ethics, 59(4), 375–413.

Okleshen, M., & Hoyt, R. (1996). A cross-cultural comparison of ethical perspectives and decision approaches of business students: United States of America versus New Zealand. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(5), 537–549.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: a meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24(3), 403–441.

Orpen, C. (1987). The attitudes of United States and South African managers to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 6(2), 89–96.

Parashar, S., Dhar, S., & Dhar, U. (2004). Perception of values: a study of future professionals. Journal of Human Values, 10(2), 143–152.

Paul, K., Zalka, L. M., Downes, M., Perry, S., & Friday, S. (1997). U.S. consumer sensitivity to corporate social performance: development of A scale. Business and Society, 36(4), 408–418.

Pettit, P. (2005). Responsibility incorporated. Paper presented at the Kadish Center for Morality, Law and Public Affairs, Workshop in Law, Philosophy and Political Theory, March 23, 2005.

Pirsch, J., Gupta, S., & Grau, S. L. (2007). A framework for understanding corporate social responsibility programs as a continuum: an exploratory study. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(2), 125–140.

Posner, B. Z., & Schmidt, W. H. (1987). Ethics in American companies: a managerial perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 5, 383–391.

Posner, B. Z., & Schmidt, W. H. (1996). The values of business and federal government executives: more different than alike. Public Personnel Management, 25(3), 277–289.

Prahalad, C. K., & Hammond, A. (2002). Serving the world's poor, profitably. Harvard Business Review, 80(9), 48–58.

Qi, W. X., & Tang, H. W. (2004). The social and cultural background of contemporary moral education in China. Journal of Moral Education, 33(4), 465–480.

Rashid, M. Z. A., & Ibrahim, S. (2002). Executive and management attitudes towards corporate social responsibility. Corporate Governance, 2(4), 10–16.

Ravlin, E. C. (1995). Values. In N. Nicholson (Ed.), The Blackwell Encyclopedic dictionary of organizational behavior (p. 598). Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishers.

Redfern, K., & Crawford, J. (2004). An empirical investigation of the influence of modernisation on the moral judgements of managers in the People’s Republic of China. Cross Cultural Management, 11(1), 48–61.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values (p. 5). New York: Free Press.

Ruegger, D., & King, E. W. (1992). A study of the effect of age and gender upon student business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(3), 179–186.

Russo, M., & Fouts, P. A. (1997). A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 534–559.

Sankaran, S., & Bui, T. (2003). Ethical attitudes among accounting majors: an empirical study. Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge, 3(1/2), 71–77.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65.

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 19–45.

Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 48(1), 23–47.

Schwartz, S., & Bardi, A. (2001). Value hierarchies across cultures – taking a similarities perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(3), 268–290.

Selznick, P. (1957). Leadership in administration. New York, NY: Harper & Row Publishers.

Sethi, S. P. (1975). Dimensions of corporate social performance: an analytic framework. California Management Review, 17, 58–64.

Shafer, W. E., Lee, G. M., & Fukukawa, K. (2007). Values and the perceived importance of ethics and social responsibility: the U.S. versus China. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(3), 265–284.

Sheldon, O. (1924). The philosophy of management (pp. 70–99). London, England: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons Ltd.

Siltaoja, M. E. (2006). Value priorities as combining core factors between CSR and reputation – a qualitative study. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(1), 91–111.

Simon, H. A. (1945). Administrative behaviour. New York: Free Press.

Smith, N. C. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: whether or how? California Management Review, 45(4), 52–76.

Sonnenfeld, J. (1981). Executive apologies for price fixing: role biased perceptions of causality. Academy of Management Journal, 24(1), 192–198.

Stern, P. C., & Dietz, T. (1994). The value basis of environmental concern. Journal of Social Issues, 50(3), 65–84.

Terpstra, D. E., Rozell, E. J., & Robinson, R. K. (1993). The influence of personality and demographic variables on ethical decisions related to insider trading. The Journal of Psychology, 127(4), 375–389.

Tian, H. (2006). Corporate social responsibility and advancing mechanism (pp. 5–30). Beijing: Economy & Management Publishing House (in Chinese).

Tse, A. C. B., & Au, A. K. M. (1997). Are New Zealand business students more unethical than non-business students? Journal of Business Ethics, 16(4), 445–450.

VanSandt, C. V. (2003). The relationship between ethical work climate and moral awareness. Business & Society, 42(1), 144–152.

Waddock, S. A., & Graves, S. B. (1997). The corporate social performance- financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18(4), 303–319.

Waldman, D., Siegel, D., & Javidan, M. (2004). CEO transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility. Rensselaer Working Papers in Economics with number 0415, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Walton, C. (1967). Corporate social responsibilities. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Wartick, S. L., & Cochran, P. L. (1985). The evolution of the corporate social performance model. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 758–769.

Whitcomb, L. L., Erdener, C. B., & Li, C. (1998). Business ethical values in China and the U.S. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(8), 839–852.

Williams, R. M., Jr. (1979). Change and stability in values and value systems: a sociological perspective. In M. Rokeach (Ed.), Understanding human values. New York: The Free Press.

Williams, R. M., Jr. (1968). The concept of values. In D. L. Sills (Ed.), International Encyclopaedia of Social Sciences, 16, 283–287.

Wimalasiri, J. S., Pavri, F., & Jalil, A. A. K. (1996). An empirical study of moral reasoning among managers in Singapore. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(12), 1331–1341.

Wong, Y. Y., Maher, T. E., Evans, N. A., & Nicholson, J. D. (1998). Neo-Confucianism: the bane of foreign firms in China. Management Research News, 21(1), 13–22.

Wood, D. J. (1991). Corporate social performance revisited. Academy of Management Review, 16(4), 691–718.

Wu, C. F. (2003). A study of the adjustment of ethical recognition and ethical decision-making of managers-to-be across the Taiwan Strait before and after receiving a business ethics education. Journal Of Business Ethics, 45(4), 291–307.

Xi, J. Y., Sun, Y. X., & Xiao, J. J. (2006). Chinese youth in transition, the chinese economy series. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Zhou, Z. C., Ou, P., & Enderle, G. (2009). Business ethics education for MBA students in China: current status and future prospects. Journal of Business ethics Education, 6, 103–118.

Zhu, X. M., & Liu, C. L. (2004). Teacher training for moral education in China. Journal of Moral Education, 33(4), 481–494.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Juslin, H. Values and Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions of Chinese University Students. J Acad Ethics 10, 57–82 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-012-9148-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-012-9148-5