Abstract

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a lasting ethical position toward the organization, the market and the society. For higher education institutions (HEI), CSR is a very timely topic, they must invest in their strategies and build a responsible approach into, not only their management activities, but also in their education programs. The purpose of this research is to examine the type of perceptions students have regarding CSR and, to examine if sociodemographic variables (such as, gender, age, professional experience and academic degree), influence the students’ perceptions of CSR. We collected data using a sample of 194 students from Polytechnic of Porto. The results suggest that the students’ perceptions present different dimensions that can be grouped in i) pro CSR, ii) resistant CSR and iii) secondary CSR, and the sociodemographic variables do not present statistically significant differences in the perceptions of the different students under study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Globalization causes constant changes in the business environment and economic progress and as a result it is essential to recognize social responsibility as an important corporate decision (Mcguire et al. 1988), and to understand that this phenomenon emerged with the growing importance of the stakeholder theory (Freeman 1984).

In general, social responsibility can be described as the set of corporate actions taken in order to improve economic, social and environmental conditions and which go beyond legal impositions (Godfrey et al. 2009). As such, having in mind that social responsibility is a growing concern in the business environment, it becomes crucial to investigate the perceptions of future employees/employers/entrepreneurs, that is to say of today’s students, on this matter. Fitzpatrick's (2013) examined the perceptions of CSR among a sample of business students in the United States and investigated the relationship between gender, work experience, and spirituality and CSR perceptions.

In this paper, taking in account that national culture influences perceptions and provides a preconceived reference framework through which people interpret reality (Usunier and Lee 2013), we applied Fitzpatrick’s questions to a group of students of a different nationality. We believe that different cultures may attach different meanings to the same concepts. Literature shows differences in CSR perceptions among students from different countries (Wong et al. 2010; Pätäri et al. 2017). In this line of thought, our main objectives are to observe if Portuguese students have different perceptions regarding the CSR and, in line with the hypotheses suggested by Fitzpatrick's (2013), to verify if sociodemographic variables like age, gender, academic degree and professional experience influence students’ perceptions on this matter. Moreover, we want to identify different dimensions on these perceptions, in order to detect similar students’ perceptions in the survey.

The paper starts with a literature review, pointing out the relevance of the subject, namely in what regards higher education institutions (HEI). This review also shows the definitions, the importance, the motivations and the initiatives that lead to socially responsible actions, as well as a set of hypotheses and the description of the reasons for studying students’ perceptions on this topic.

An empirical study was carried out with a sample of students from a Portuguese HEI, using Fitzpatrick's (2013) questions and different univariate and multivariate statistical techniques that met our requirements.

This investigation contributes to CSR body of knowledge and provides inputs for HEI.

2 Literature review

2.1 Corporate social responsibility

Globalization implies changes in the business environment and economic progress and as a result CSR becomes an important corporate decision (Mcguire et al. 1988), in order to match the expectations of new businesses and stakeholders (Dahlsrud 2008). CSR is a concept whereby organizations consider several interests and concerns of society by taking responsibility for the impact of their activities on customers, suppliers, employees, shareholders, communities and other stakeholders, as well as on the environment (Wymer and Rundle-thiele 2017). However, despite being a current topic, there is no consensus regarding how CSR should be defined, because there is a multitude of concepts, based on different dimensions adopted by several authors, although some common points may be found (Dahlsrud 2008), as we can see in the following table (Table 1).

We can assume that CSR should be involved in a triple bottom line that considers that an organization’s success depends on its economic profitability, environmental sustainability and social performance (Zadek et al. 2003). Thus, CSR can trigger corporate social progress, translated into various initiatives both internal or external to the organization, such as changes in production methods, reduction of environmental impacts, improvement of employees’ satisfaction and different relationships across the value chain, as well as external investment in local communities’ infrastructures and the development of actions in the community (Aguilera et al. 2007). In this way, social responsibility must be integrated into the strategy of an organization by means of, for example, differentiating products with social characteristics, so as to create consumer loyalty to the brand and enhance the company’s profile as being reliable and honest (Siegel and Vitaliano 2007).

According to Fitzpatrick (2013, p. 86), “the number of corporate social responsibility related to shareholder proposals has significantly increased in recent years along with the number and dollar volume of socially responsible investment funds”. CSR is an increasingly unescapable phenomenon on the European and North American economic and political landscape (Doh and Guay 2006), and thus, this is a much-discussed topic in the economic and academic context. This is so because critics of the business system have increased, questioning the performance of businesses and the power of large corporations (Jones 1980), conditioning changes in society, with the need to sanction certain business behaviours related to unethical and irresponsible conducts (Gavin and Maynard 1975). This means that, in some occasions, large organizations, when seeking to capture value and maximize profits, may engage in unethical conducts, making use of their dominant power and reducing the benefit to society, so instead of adopting existing procedures, they should work on creating value (Santos 2012).

The importance of considering other needs regarding other stakeholders is portrayed in more recent research (Fitzpatrick 2013). In this perspective, the stakeholder theory has become increasingly more relevant, being a stakeholder any interested party that may affect or be affected by the organization, including shareholders, suppliers, customers, governments and other groups (Gallardo-Vázquez and Sanchez-Hernandez 2014). According to Freeman (1984), the phenomenon of CSR emerged from this theory and as a result, in recent years, the relevance of CSR has grown, representing not only a business opportunity but also a reflection of the expectations of the different stakeholders, thus demonstrating a strong connection with the company’s success, competitiveness and strategy (Closon et al. 2015; Gallardo-Vázquez and Sanchez-Hernandez 2014). For Hsieh, Curtis, & Smith (2008, p. 10), “it is apparent that stakeholders play an important part in organization’s strategic management”, therefore, having in mind that this is a dynamic process, the organization is likely to adopt different strategies with different stakeholders.

Although not entirely spread among all business areas (Sánchez-Hernández and Mainardes 2016), CSR has been the object of a new line of research considering other organisations like public administration, and particularly higher education institutions (HEI) (Vallaeys et al. 2009; Vázquez et al. 2014, 2016). In this context, CSR can be considered as a policy of ethical performance of HEI through responsible management in several areas like teaching, research, extension and management (Vallaeys et al. 2009), whereby, reflecting the needs of companies and society, business schools have introduced ethics and social responsibility themes into their programs (Assudani et al. 2011).

In the context of an HEI, CSR should cover aspects of the planning, design, implementation and evaluation phases of its activities related to teaching, research and knowledge transfer (Esfijani et al. 2013). The concept of University Social Responsibility (USR) encompasses the role of HEIs in: the democratization of the education service; the design of curricula adapted to the needs of the labor market; the quality assurance of graduates; the minimization of environmental impacts, the adequacy of research activities and the provision of services to the needs of society (Esfijani et al. 2013). HEIs are institutions that affect society through the provision of educational services and the transfer of knowledge, guided by ethical principles, good governance, respect for the environment, social involvement and promotion of values (Vallaeys et al. 2009).

There are numerous terms and definitions for USR (Wigmore-Álvarez and Ruiz-Lozano 2012; Esfijani et al. 2013; Vázquez et al. 2014, 2016). Taking into account the research developed by Esfijani, Hussain, & Chang (2013, p. 280) we assume USR as “a concept whereby university integrates all of its functions and activities with the society needs through active engagement with its communities in an ethical and transparent manner which aimed to meet all stakeholders’ expectations”. This research highlighted stakeholders as the most important component of USR and the main stakeholder to be considered is community, namely: university community (students, academic staff, non-academic staff); local community (citizens, NGOs, partners, sponsors, organizations, practitioner) and global community (public, sponsors, competitors, organizations, practitioners).

The impacts of USR can be traced at different levels - teaching, research, internal management and extension (Lidgren et al. 2006; Velazquez et al. 2006; Vallaeys et al. 2009; Lozano et al. 2013). Considering students as key stakeholders of HEIs (Fitzpatrick 2013; Sánchez-Hernández and Mainardes 2016; Vázquez et al. 2014, 2016), it is important to integrate contents on sustainable development across the curricula (Lidgren et al. 2006; Ceulemans and De Prins 2010) because it has a direct impact on how students understand and interpret the world around them (Vallaeys et al. 2009).

Thus, HEI are critical elements in preparing leaders who are concerned with ethics and social responsibility issues in business (Alsop 2006) and, as a consequence, academic interest in CSR has increased (Wymer and Rundle-thiele 2017). At the same time, it is important to mention the HEI intense competition scenario, and the way this fact combined with demographic changes in the population have forced HEIs to be more focused on students (Sánchez-Hernández and Mainardes 2016).

2.1.1 Students’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility

Having in mind that CSR is a growing concern in the business environment, it is of interest to investigate the perceptions of future employees/employers/entrepreneurs, that is of today’s students, since “(it) is increasingly seen as an important component of business education” (Assudani et al. 2011, p. 103). Therefore, business schools should contribute to the education of not only good managers but also good citizens (Wymer and Rundle-thiele 2017), preparing socially responsible individuals, on the basis that, ethical education improves ethical awareness and moral reasoning (Lau 2010).

Some empirical research has been conducted to measure students’ perception of social responsibility (Elias 2004) and it is possible to identify some categories and dimensions (González-Rodríguez et al. 2013). Being clear that CSR contributes to the survival, sustainability and public awareness of organizations and that it has become a strategic tool, students’ perceptions about CSR have significant variations (Mcguire et al. 1988).

Different dimensions identified include noneconomic aspects of social responsibility, as well as philanthropy (Akbaş et al. 2012; Wong et al. 2010); regulatory requirement or legal obligations (Akbaş et al. 2012; Arli et al. 2014; Thomas and Little 2011; Wong et al. 2010); competitive advantage and ability to innovate and learn (Thomas and Little 2011) or economic responsibilities (Akbaş et al. 2012; Arli et al. 2014; Penteado et al. 2013); positive perceptions concerning overall, social, and environmental CSR (Pätäri et al. 2017); and ethical responsibilities (Akbaş et al. 2012; Arli et al. 2014); we also find profitability, long-term success and short-term success as dimensions identified in researches that use the instrument “perceived role of ethics and social responsibility” (PRESOR) (Elias 2004; Fitzpatrick 2013; Singhapakdi et al. 1996).

Although it is important to mention that CSR has grown differently in Western and Eastern counterparts, as well as within different regions and therefore changes in consumers’ perceptions may seem probable (González-Rodríguez et al. 2013), at the same time, as more examples of corporate hypocrisy become public, consumers develop an inherent general scepticism towards firms’ CSR claims (Connors et al. 2017). Therefore, literature also identifies dimensions related to CSR perceptions that are not so positive, for example it is generally believed that companies may improve their image if they are seen as being responsive to public concerns (Wals 2007), so CSR may be seen as an artificial performance; also students embracing altruistic values have more positive CSR perceptions than students with egotistic values (Pätäri et al. 2017).

Particularly in developed countries there is a greater variety of ethical products and a greater availability of resources that allow consumers to pay higher prices and support greater social awareness (Arli et al. 2014). In contrast, although institutions aim at making students aware of the importance of assuming ethical and socially responsible practices, facts show that students do not act accordingly and still prioritize maximizing profit as the main management guideline in detriment of the CSR (Assudani et al. 2011; Tormo-Carbó et al. 2016; Wymer and Rundle-thiele 2017).

Therefore, since there is no consensus regarding how CSR should be defined, as the multiplicity of concepts mentioned before prove, it seems interesting to, based on these different dimensions, identify the different dimensions on students’ perceptions of CSR, in order to analyse if there is more than one factor in this content. Thus, taking into account that literature shows that nationality is associated with students’ perceptions of CSR (Wong et al. 2010; Pätäri et al. 2017) and that the research developed by Fitzpatrick's (2013) in an American HEI does not analyse the different dimensions on students’ perceptions about CSR, within the present framework, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1: Students’ perceptions of CSR can be considered in different dimensions

However, in addition to the specificity of cultural factors and resource availability of each country, sociodemographic characteristics are also considered as elements that can influence perceptions about CSR and can determine ethical decision making (Arli et al. 2014; Fitzpatrick 2013; González-Rodríguez et al. 2013; Wong et al. 2010). So, sociodemographic variables play an important role and influence the empowerment of individuals in issues related to CSR, specifically those related to environmental areas, and the analysis of these variables may provide organizations with a better understanding of the stakeholders’ needs (Diamantopoulos et al. 2003), and looking specifically at students’ perceptions of CSR, we can assert that sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, work experience and academic degree, are important in shaping and influencing students’ perceptions of CSR (Fitzpatrick 2013). Based on these researches, we define the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 2: Sociodemographic students’ characteristics can influence their perception of CSR

This hypothesis can be subdivided in several sociodemographic characteristics. Some studies refer age as an influential factor (Gavin and Maynard 1975; Ruegger and King 1992; Fitzpatrick 2013) but investigation on this matter is still incipient. While some consider that older individuals respond more favourably to the question of CSR, because they believe that organizations aim at higher levels of fairness (Gavin and Maynard 1975), the most recent literature points out that the younger ones are more sensitive to this concern (Ruegger and King 1992; Fitzpatrick 2013; Pätäri et al. 2017) and show a positive orientation towards the issue of CSR (Arlow 1991). Thus, it is suggested that:

-

Hypothesis 2.1.: Age positively influences students’ perceptions of CSR

At the same time, analyses of students’ perceptions indicate that students with higher levels of education have a better understanding of CSR in today’s business environment (Fitzpatrick 2013), that is, students, especially in management, are more prone to favourable attitudes toward CSR, with a genuine concern for aligning organizations with the well-being of society (Kolodinsky et al. 2010), so we can set the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 2.2.: Academic degree positively influences the students’ perceptions of CSR

In addition, gender may also have an influence on ethical decision-making. According to some studies, female students exhibit greater sensitivity to CSR issues (Ruegger and King 1992; Arli et al. 2014; Diamantopoulos et al. 2003; Fatoki 2016; Fitzpatrick 2013; González-Rodríguez et al. 2013; Pätäri et al. 2017). Women have a greater capacity to balance the organization’s interests with other stakeholders (Arlow 1991), since they better understand the benefits that socially responsible actions can bring to the marketing of an organization whereas men are more reluctant to accept this idea and believe that organizations often take advantage of consumers by asking their support to certain causes (Arli et al. 2014), then the hypothesis to be tested is:

-

Hypothesis 2.3.: Gender influences the students’ perceptions of CSR

Finally, according to Fitzpatrick (2013), work experience is important for shaping the perceptions of CSR. Those who acquire greater experience have a more favourable idea of the relevance of the theme, since social policies with positive effects affect the willingness and satisfaction of employees within the organization and contribute to initiatives that call for social change (Aguilera et al. 2007), so the hypothesis to be tested is:

-

Hypothesis 2.4.: The professional experience positively influences the students’ perceptions of CSR

3 Methodology

A quantitative methodology was applied to analyse if the suggested hypotheses are verified. The goals are to understand whether perceptions under analysis can be associated with different factors and to understand the role of students’ sociodemographic characteristics in their perceptions about questions related with CSR.

We used an adapted version of the original PRESOR (perceived role of ethics and social responsibility), which was originally developed to measure marketers’ perceptions regarding the importance of ethics and social responsibility (Singhapakdi et al. 1996) and later, a slightly adapted version was used to assess students’ perceptions of CSR (Fitzpatrick 2013). The original dimensions of PRESOR include social responsibility and profitability (an individual who is high on these dimensions will tend to believe that ethics and social responsibility will play a very important role in improving profitability and organizational competitiveness), long term gains (ethics and social responsibility is considered important for the long-term success of the firm) and short-term gains (ethics and social responsibility are considered important in achieving short-term gains) (Singhapakdi et al. 1996). Our survey focuses on analysing students’ different perceptions regarding CSR, considering Fitzpatrick’s research (2013), also including demographic information (gender, age, academic degree and employment/professional situation). The questions about students’ perceptions are shown in Table 4, and based in prior research we expect to find the relations that are mentioned in Table 2.

We collected our data in School of Management and Technology (one of the seven schools of Polytechnic of Porto - IPP), IPP is the largest public polytechnic in Portugal, with around 18,500 students, and the fourth biggest HEI in Portugal. Online surveys were delivered to several students of the School of Management and Technology, between March and April 2016, and a convenience sample of 194 responses was collected. A 16-question survey was administered (scale ranges from 1 (not important) to 9 (extremely important)), plus five sociodemographic questions. Data was analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 and IBM SPSS Amos 24 software and univariate analyses, mainly descriptive analysis, t-test and Pearson test, and multivariate analyses, namely exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis and MANOVA, were performed. These statistical techniques were selected according to the research hypothesis.

Table 3 shows that 57.2% of the students were female and 42.8% male. The majority (74.2%) was between 17 and 26 years of age, but there were respondents from all age intervals including those between 17 and 21 and 42–50, (this last one is the least significant with only 7 students). About 84.5% of the students were single and the remaining (15.5%) were married or in a civil union. In what concerns the academic degree, the majority of the respondents (59.3%) attend an undergraduate course, 19.6% a master’s degree and 19.1% professional technical courses. In what regards the employment situation, the majority of the respondents (60.8%) were full time students, while only 25.8% had a full time job (student worker).

4 Results

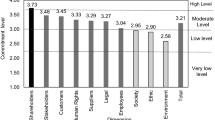

Considering students’ perception, Table 4 lists and summarizes the set of perceptions about CSR analysed in this survey, similar to Fitzpatrick (2013). In the same table, it is possible to see the means values, and to conclude that the perceptions with the highest mean are those in favour of CSR, for example perceptions 1, 6, 9, 12 and 15. Perceptions 5, 8, 13 and 16, which in general state that CSR is not an important decision to be considered by organizations have lower averages.

Considering this set of perceptions, we performed a factor analysis, in line with our first objective, which is the identification of different dimensions on students’ perceptions of CSR.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure obtained is 0.792, indicating that the sample is adequate to perform factor analysis. Besides that, the level of significance of the Bartlett Test is approximately 0 (≈ 0.000), so at a significance level of 5%, the sample is appropriate to this technique. From the results presented in Table 5, in particular taking into account the Individual Measures of Sample Adequacy (MSA) values, all variables have MSA values greater than 0.5 and thus, they are all considered important for the analysis and have sufficient in common with the order variables to obtain viability measures. The values of the matrix of the rotated components show that variables are interrelated to each other, being extracted three constructs with a variance explained by the factors of approximately 52% of the variance of the total variables involved. Thus, we can identify three dimensions, and in the light of the factor loadings presented in Table 5, and following the previous interpretations of PRESOR (Fitzpatrick 2013; Singhapakdi et al. 1996), we have the following three components: component 1 which includes favourable perceptions of CSR (with an average of 6.75, scales ranges from 1 to 9); component 2 which includes perceptions that challenge the importance of CSR (with an average of 3.7), and component 3 that includes items related to the enterprise prioritization, putting CSR in a second plan (with an average of 5.26).

Through a reliability analysis, using the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient, it is possible to confirm the results presented by the exploratory factorial analysis taking into account that the values presented in Table 5 are higher than 0.70 and therefore the measures are reliable (Pestana and Gageiro 2008; Hair et al. 2010). In addition, a confirmatory factorial analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS Amos 24 software to evaluate the quality of the overall adjustment of the results obtained in the exploratory factorial analysis, with the following indicative values of good fit: CFI higher than 0.9, PCFI higher than 0.6, CMIN/DF less than 2 and RMSEA less than 0.05 (Maroco 2003; Hair et al. 2010). The obtained values (CFI = 0,936; PCFI = 0,695; CMIN/DF = 1516; RMSEA = 0,052) suggest the model provides a good overall fit.

As such, through the factor analysis, it is possible to conclude that these perceptions’ results show that students’ perceptions of CSR assume different dimensions and students do not always refer to CSR as a fundamental concern for the organizations. Therefore, the first objective was achieved, and we verified hypothesis 1.

In order to clarify if the sociodemographic variables studied, namely age, gender, academic degree and professional experience influence the students’ perception of CSR, a Pearson test was used in the first analysis to determine if there is a correlation between the variables under study. That is, a Pearson test was made between the sociodemographic variables under study and the three dimensions obtained by the factor analysis that group the students’ perceptions of CSR. Based on the p-value obtained, considering a significance level of 5%, we conclude that the variables are independent and not correlated, which also means that in this approach, and in general, there is no statistically significant evidence to consider that the 3 different dimensions of the Students’ perceptions about CSR: favourable perceptions to CSR; perceptions that challenge the importance of CSR; and enterprise prioritization, putting CSR in a second plan, are correlated with the sociodemographic characteristics of the students. This evidence stands when we particularize the sociodemographic characteristics of the students.

Thus, to answer three of the four hypotheses suggested in the literature review referring specifically to the sociodemographic variables, we used a MANOVA. This technique intends to evaluate if there are statistically significant differences between several groups, regarding two or more factors, as an alternative to the use of several ANOVAs (Maroco 2003). Thus, for the purposes of the MANOVA analysis, perceptions variables will be considered as dependent, being considered continuous and the independent variable will be respectively age, academic degree and experience, to test hypothesis 2.1., 2.2. and 2. 4.. However, for the use of multivariate analysis of variance, some assumptions must be fulfilled: multivariate normality, homoscedasticity and existence of correlation between independent variables. For this, a significance level of 5% was considered and Table 6 (see appendix) summarizes the validation of the assumptions for the hypotheses under investigation, justifying the use of MANOVA.

Concerning the influence of the age in students’ perceptions of CSR (hypothesis 2.1.) it was obtained a p-value ≈ 0.371 for the Wilks’ Lambda test, meaning that the dependent variable does not have a statistically significant effect on the independent variables. However, by the p-values obtained in the Tests of Between-Subjects Effects it is observed that students’ perception, based on their age, was only statistically significant for perception 5: “The most important concern for a firm/organization is making a profit, even if it means bending or breaking the rules”, with a p-value ≈ 0.033. After this identification, the ANOVA technique and Tukey’s post-hoc tests are performed to determine if there are statistically significant differences between age intervals answers to this perception 5, however, the p-values presented by classes are all higher than 0.05, which indicates that there are no relevant differences between age groups. As such, we conclude that hypothesis 2.1.: “Age positively influences students’ perceptions of CSR”, is not verified.

Then, by doing the same analysis, with the dependent variable, academic degree, it was obtained a p-value ≈ 0,258 for the Wilks’ Lambda test, which means that the dependent variable does not have a statistically significant effect on the independent. Besides that, the p-values obtained in the Tests of Between-Subjects Effects were all higher than 0,05, then it is observed that the academic degree does not have as consequence a statistically difference in the perceptions of the students. In this way, we must reject the hypothesis 2.2.: “The academic degree positively influences the students’ perceptions of CSR”.

Still using the MANOVA technique, having as a dependent variable experience, we analyse the perceptions of the students (having in mind the hypothesis 2.4.). It was obtained a p-value ≈ 0.748 for the Wilks’ Lambda test, which means that the experience does not have a statistically significant effect on the students’ perceptions of CSR. Besides that, the p-values obtained in the Tests of Between-Subjects Effects were all higher than 0.05, then it is observed that the perception of the students, based on their current employment situation, does not verify statistically significant differences, confirming that we should reject hypothesis 2.4.: “The professional experience positively influences the students’ perceptions of CSR”.

To test hypothesis 2.3. “Gender influences the students’ perceptions of CSR” and expecting female gender to be more sensitive to the importance of CSR, we used a t-test, investigating whether there is a statistically significant relationship between gender and students’ perceptions of CSR, that is, the means for the two groups are compared, considering each perception. The Levene test allows to consider that equality of variances is verified in almost all perceptions, only the perception 13:” If survival of a firm/organization is at stake, then you must forget about ethics and social responsibility”, has a p-value less than 0.05. However, examining the p-values presented by the t-tests, the conclusion is that only for the perception 1: “Being ethical and socially responsible is the most important thing a firm/organization can do” there are differences between the means of the two groups, male and female students. As such, the visualization of the confidence interval, obtained for this perception, clarifies that being the values positive, it is assumed that female students have more favourable perceptions for this question. However, in a global way, we should reject hypothesis 2.3.: “The gender influences the students’ perceptions of CSR”.

5 Discussion and conclusions

In general, based on one of the main objectives of determining whether CSR students ‘perceptions differed, we can conclude that, in a first analysis of the means of the students’ answers about the perceptions, we could divide the perceptions in two distinct groups. Namely those that obtained a higher average, and therefore, identified with favourable perceptions of CSR, and others with lower means that defy CSR perceptions.

That is, from this analysis we can expect the verification of the hypothesis 1 “Students’ perceptions about CSR can be considered in different dimensions”, which confirms what has been described in the literature review, namely that although students are aware of ethical and socially responsible practices/strategies, they do not always make responsible decisions and assume responsible behaviours that benefit society (Assudani et al. 2011). These results are confirmed by the results obtained by factor analysis, which defined three principal dimensions in the students’ perceptions of CSR:

-

favourable perceptions of CSR

-

perceptions that challenge the importance of CSR

-

enterprise prioritization, putting CSR in a second plan.

The existing research shows that the majority of students display positive attitudes and perceptions toward sustainability and CSR strategies (Bahaee et al. 2014). At the same time, the new human values era is linked with solidarity, quality of life, environmental concerns, welfare and interest with others (González-Rodríguez et al. 2013), so there are high social perceptions related to CSR. Our first dimension includes favourable perceptions to CSR, with a mean of 6.75, and that can be seen as pro CSR, confirming what is reported in the literature that CSR is increasingly recognized as an important strategic decision, with increasing and positive benefits to organizations (Mcguire et al. 1988), being important for its success and competitiveness (Gallardo-Vázquez and Sanchez-Hernandez 2014).

As CSR scepticism has a strong impact on consumers’ attitudes and perceptions, there are some less positive perceptions towards CSR that may lead people to adopt a low-level mind-set when processing CSR information (Connors et al. 2017). Component 2 includes perceptions that challenge the importance of CSR and include perceptions resistant to CSR. One of the possible explanations may be linked to the fact that the ethical education adopted by HEI is still incipient, as Wymer & Rundle-Thiele (2017, p. 28), state in their study “only about one-third of our universities offered a sustainability-related course”. Because teachers still have little information about the importance of CSR and feel disqualified to teach ethics and sometimes believe that they cannot change students’ ethical behaviours (Wymer and Rundle-thiele 2017), this can lead to students’ lack of awareness of this issue.

Finally, component 3 includes items related to company prioritization, even though products/services that are perceived as ‘good’ or ‘ethical’ may increase competitive advantage (Brei and Böhm 2011), this set of answers place CSR in a second plan, in the backstage, with an average of 5.26. These students’ perceptions consider CSR as secondary, they consider that in order for the organization to be socially responsible it must commit its resources in favour of society and the environment in particular, and in turn, this socially responsible behaviour entails costs that call into question the main management policy that consists in maximizing wealth (Wymer and Rundle-thiele 2017). The materialistic interest of managers, driven by the desire for power, control and wealth, stands above ethical and socially responsible values, conditioning decision-making in favour of CSR, therefore, CSR is prioritized only when it is seen as profitable, and capable of promoting the interests of the organization (Giacalone and Thompson 2006).

Concerning the second major objective of this study, which refers to the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on students’ perceptions of CSR, the fact is that there were no statistically significant evidences for differentiation per age, gender, academic degree and professional experience on this matter, strongly indicating that students’ CSR perceptions do not suffer influences for these sociodemographic characteristics, showing a certain level of similarity between them. In some researches also on students’ perceptions, it is possible to verify the inexistence of statistically significant effect from gender and age (Burcea and Marinescu 2011; Pätäri et al. 2017). This may mean that regardless of these variables, students are increasingly aware of the importance of CSR and have a positive perception about it. Although, considering gender, our results evidence different perceptions in one item (being ethical and socially responsible is the most important thing a firm/organization can do) and considering that this item is, at the same time, wide-ranging and geocentric to the topic, we can mention that female students may be slightly more sensitive to this question. Literature shows gender as a significant factor, particularly when it stresses how female gender has a more positive perception, when compared to the male gender, in what regards ethical aspects, social initiative, as well as CSR (Arli et al. 2014; Arlow 1991; Fitzpatrick 2013; González-Rodríguez et al. 2013). We also performed a Pearson test between the sociodemographic variables and the three different students’ dimensions of perceptions about CSR, obtained in the factor analysis, and again the results do not reveal the influence of these variables on the different perceptions that the students have about CSR.

In conclusion, we can mention the existence of three different dimensions of students’ perceptions: i) pro CSR, ii) resistant CSR and iii) secondary CSR, we can say that favourable perceptions to CSR present the highest average, showing that, generally, students value CSR. So, CSR is considered important for the majority, though there are dissimilar perceptions, and thus the meaning and importance of CSR students’ perceptions can be questioned. In addition, the results show that variables such as age, gender, academic degree and professional experience of each student do not present statistically significant differences in the perceptions that each student has about CSR.

This research has important managerial implications for HEIs. Students as future employees/employers/entrepreneurs and as consumers evaluate CSR programs. Transformation paths toward a more sustainable activity will be shaped by the dissemination of sustainable manufacture and consumption patterns (Pülzl et al. 2014), and young people are potentially very significant agents of change (Pätäri et al. 2017). It is particularly vital to understand and proactively anticipate how the sustainable and ethical attitudes of students as employees/employers/entrepreneurs and as consumers grow and how is their ethical, responsible and sustainable behaviour.

In what concerns limitations of the study, one can mention that the number of HEIs involved is one important constraint, as it is the fact that the questionnaire did not consider context-specific issues. In addition, the low number of respondents limits the generalization of the findings. Consequently, future research might include a more extensive and heterogeneous sample, extending to other HEIs and students of different ages and areas, in order to better understand whether the hypotheses suggested in this article would lead to different conclusions.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159338.

Akbaş, H. E., Çalişkan, A. Ö., & Esen, E. (2012). An investigation on Turkish business and economics students’ perception of Corporaye social responsibility. Journal of Accounting & Taxation Studies, 5(3), 69–81.

Alsop, R. J. (2006). Business ethics education in business schools: A commentary. Journal of Management Education, 30(1), 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562905280834.

Arli, D., Bucic, T., Harris, J., & Lasmono, H. (2014). Perceptions of corporate social responsibility among Indonesian college students. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business, 15(3), 231–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/10599231.2014.934634.

Arlow, P. (1991). Personal characteristics in college students’ evaluations of business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Peter Arlow. Business Ethics, 10(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00383694.

Assudani, R. H., Chinta, R., Manolis, C., & Burns, D. J. (2011). The effect of pedagogy on students’ perceptions of the importance of ethics and social responsibility in business firms. Ethics & Behavior, 21(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2011.551467.

Bahaee, M., Perez-Batres, L. A., Pisani, M. J., Miller, V. V., & Saremi, M. (2014). Sustainable development in Iran: An exploratory study of university students’ attitudes and knowledge about sustainable developmenta. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 21(3), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1312.

Brei, V., & Böhm, S. (2011). Corporate social responsibility as cultural meaning management: A critique of the marketing of “ethical” bottled water. Business Ethics, 20(3), 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2011.01626.x.

Burcea, M., & Marinescu, P. (2011). Ae students ’ perceptions on corporate social responsibility at the academic level . Case study : The faculty. Amfiteatru Economic, 13(29), 207–220.

Ceulemans, K., & De Prins, M. (2010). Teacher’s manual and method for SD integration in curricula. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(7), 645–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.09.014.

Closon, C., Leys, C., & Hellemans, C. (2015). Perceptions of corporate social responsibility, organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 13(1), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRJIAM-09-2014-0565.

Connors, S., Anderson-MacDonald, S., & Thomson, M. (2017). Overcoming the ‘window dressing’ effect: Mitigating the negative effects of inherent skepticism towards corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(3), 599–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2858-z.

Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.132.

Diamantopoulos, A., Schlegelmilch, B. B., Sinkovics, R. R., & Bohlen, G. M. (2003). Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. Journal of Business Research, 56(6), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00241-7.

Doh, J. P., & Guay, T. R. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 43(1), 47–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00582.x.

Elias, R. Z. (2004). An examination of business students’ perception of corporate social responsibilities before and after bankruptcies. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(3), 267–281.

Esfijani, A., Hussain, F., & Chang, E. (2013). University social responsibility ontology. International Journal of Engineering Intelligent Systems, 4(December), 271–281.

Fatoki, O. (2016). Gender and the perception of corporate social responsibility by university students in South Africa. Gender & Behaviour, 14(3), 7574–7588.

Fitzpatrick, J. (2013). Business students’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility. College Student Journal, 47(1), 86–96.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A Stakholder approach. Journal of Management Studies, 29. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139192675.

Gallardo-Vázquez, D., & Sanchez-Hernandez, M. I. (2014). Measuring corporate social responsibility for competitive success at a regional level. Journal of Cleaner Production, 72, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.02.051.

Gavin, J. F., & Maynard, W. S. (1975). Perceptions of corporate social responsibility. Personnel Psychology, 28(3), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01545.x.

Giacalone, R. A., & Thompson, K. R. (2006). Business ethics and social responsibility education: Shifting the worldview. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(3), 266–277.

Godfrey, P. C., Merrill, C. B., & Hansen, J. M. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 30(4), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.750.

González-Rodríguez, M. R., Díaz-Fernández, M. C., Pawlak, M., & Simonetti, B. (2013). Perceptions of students university of corporate social responsibility. Quality and Quantity, 47(4), 2361–2377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-012-9781-5.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis - a global perspective (Seventh ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

Hsieh, J., Curtis, K. P., & Smith, A. W. (2008). Implications of stakeholder concept and market orientation in the US nonprofit arts context. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 5(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-008-0001-x.

Jones, T. M. (1980). Corporate social responsibility revisited, redefined. California Management Review, 22(3), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/41164877.

Kolodinsky, R. W., Madden, T. M., Zisk, D. S., & Henkel, E. T. (2010). Attitudes about corporate social responsibility: Business student predictors. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(2), 167–181.

Lau, C. L. L. (2010). A step forward: Ethics education matters! Journal of Business Ethics, 92(4), 565–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0173-2.

Lidgren, A., Rodhe, H., & Huisingh, D. (2006). A systemic approach to incorporate sustainability into university courses and curricula. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(9), 797–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.12.011.

Lozano, R., Lukman, R., Lozano, F. J., Huisingh, D., & Lambrechts, W. (2013). Declarations for sustainability in higher education: Becoming better leaders, through addressing the university system. Journal of Cleaner Production, 48, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.10.006.

Maroco, J. (2003). Análise Estatística (2nd ed.). Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

Mcguire, J. B., Sundgren, A., & Schneeweis, T. (1988). Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 31(4), 854–872.

Pätäri, S., Arminen, H., Albareda, L., Puumalainen, K., & Toppinen, A. (2017). Student values and perceptions of corporate social responsibility in the forest industry on the road to a bioeconomy. Forest Policy and Economics, 85(April), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2017.10.009.

Penteado, R. d. F., Luz, L., Vasconcelos, P., Carvalho, H., & Francisco, A. (2013). Percepción de los Estudiantes de Ingeniería, Tecnología y Curso Técnico sobre Responsabilidad Social Empresarial. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 8(42), 23–24. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-27242013000300012.

Pestana, M. H., & Gageiro, J. N. (2008). Análise de Dados para a Ciências Sociais: A Complementaridade do SPSS (5 a edição). Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

Pülzl, H., Kleinschmit, D., & Arts, B. (2014). Bioeconomy – an emerging meta-discourse affecting forest discourses? Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 29(4), 1–8.

Ruegger, D., & King, E. W. (1992). A study of the effect of age and gender upon student business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(3), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00871965.

Sánchez-Hernández, M. I., & Mainardes, E. W. (2016). University social responsibility: A student base analysis in Brazil. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 13(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-016-0158-7.

Santos, F. M. (2012). A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1413-4.

Siegel, D. S., & Vitaliano, D. F. (2007). An empirical analysis of the strategic use of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 16(3), 773–792. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2007.00157.x.

Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., Rallapalli, K. C., & Kraft, K. L. (1996). The perceived role of ethics and social responsibility: A scale development. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(11), 1131–1140.

Thomas, A., & Little, C. (2011). Perceptions of corporate social responsibility between the United States and South Korea. In Proceedings for the Northeast Region Decision Sciences Institute, 26–47.

Tormo-Carbó, G., Oltra, V., Seguí-Mas, E., & Klimkiewicz, K. (2016). How effective are business ethics/CSR courses in higher education? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 228(June), 567–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.087.

Usunier, J.-C., & Lee, J. A. (2013). Marketing across cultures (6th ed.). Harlow: Pearson.

Vallaeys, F., de la Cruz, C., & Sasia, P. M. (2009). Responsabilidad social universitaria Manual de primeros pasos. In McGraw Hill.

Vázquez, J. L., Aza, C. L., & Lanero, A. (2014). Are students aware of university social responsibility? Some insights from a survey in a Spanish university. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 11(3), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-014-0114-3.

Vázquez, J. L., Aza, C. L., & Lanero, A. (2016). University social responsibility as antecedent of students’ satisfaction. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 13(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-016-0157-8.

Velazquez, L., Munguia, N., Platt, A., & Taddei, J. (2006). Sustainable university: What can be the matter? Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(9), 810–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.12.008.

Wals, A. E. J. (2007). Social Learning Towards a Sustainable World. The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic P u b l i s h e r s.

Wigmore-Álvarez, A., & Ruiz-Lozano, M. (2012). University social responsibility (USR) in the global context. Business and Professional Ethics Journal, 31(4), 475–498. https://doi.org/10.5840/bpej2012313/424.

Wong, A., Long, F., & Elankumaran, S. (2010). Business students’ perception of corporate social responsibility: The United States, China, and India. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 17, 299–310.

Wymer, W., & Rundle-thiele, S. R. (2017). Inclusion of ethics , social responsibility , and sustainability in business school curricula : A benchmark study. International Review of Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 14, 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-016-0153-z.

Zadek, S., Sabapathy, J., Døssing, H., & Swift, T. (2003). Responsible competitiveness - corporate responsibility clusters in action. Copenhagen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Teixeira, A., Ferreira, M.R., Correia, A. et al. Students’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility: evidences from a Portuguese higher education institution. Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark 15, 235–252 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-018-0199-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-018-0199-1