Abstract

In typically-developing (TD) individuals, effective emotion regulation strategies have been associated with positive outcomes in various areas, including social functioning. Although impaired social functioning is a core criterion of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), the role of emotion regulation ability in ASD has been largely ignored. This study investigated the association between emotion regulation and ASD symptomatology, with a specific emphasis on social impairment. We used parent-report questionnaires to assess the regulatory strategies and symptom severity of 145 youth with ASD. Results showed that: (1) more effective emotion regulation, defined by greater use of reappraisal, predicted less severe ASD symptomatology, and (2) greater use of reappraisal predicted less severe social impairment. Suppression was not predictive of general symptomatology or social functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The human emotional experience can be deconstructed into three components: a cognitive appraisal (of a stimulus or event), a physiological response, and a behavioral response (Gross 1998b). These three emotional processes play a critical role in all stages of an individual’s development, influencing everything from the formation of social relationships to overall quality of life (Gross and John 2003). As such, the ability to control or regulate emotion has been a focus of psychological research for many years. Emotion regulation can be defined as the combination of both automatic and effortful processes responsible for evaluating and modifying one’s emotional reactions, and facilitating adaptive behavior (Mazefsky et al. 2013; Thomspon 1994). Emotion regulation plays a fundamental role in all aspects of the emotional experience, from the evaluation of emotional stimuli to the selection of appropriate behavioral responses.

Strategies of Emotion Regulation

Most models of emotion regulation focus primarily on strategies for down-regulating (i.e., reducing the impact of) negative emotions such as sadness, anger, fear, and anxiety. One of the most highly-cited frameworks is Gross’ Process Model, which organizes a wide range of regulatory processes into several distinct categories (Gross 1998b), and places special emphasis on two strategies in particular: reappraisal and suppression (Gross and John 2003). Reappraisal involves modifying one’s cognitive interpretation of an event in order to change its personal impact (Lazarus and Alfert 1964), and takes place prior to any behavioral response (Gross and John 2003). Reappraisal is often described as cause-focused regulation (Gross 1998a); for example, focusing on the thoughtful intentions behind an undesirable gift in order to feel appreciative rather than angry. In contrast, suppression involves continually managing a behavioral response that has already been generated (Gross and John 2003). This is described as response-focused regulation (Gross 1998a); for example, concealing anger in response to losing a game, or masking disappointment after receiving an undesirable gift. Thus, reappraisal modifies the emotion you experience, while suppression modifies your display of an emotion you are already experiencing.

Most emotion researchers conclude that both reappraisal and suppression possess adaptive value, and that the selection of the most appropriate strategy is dependent on situational context (Aldao et al. 2014). However, there is substantial evidence supporting reappraisal as the more adaptive strategy overall: suppression is very cognitively demanding (Gross and John 2003) and creates a conflict between one’s inner experience and outward expression (Rogers 1951), while reappraisal is associated with more positive outcomes in affect, social relationships, and general well-being (Gross 2002; Gross and John 2003). Additionally, the use of suppression is associated with elevated physiological arousal in the sympathetic nervous system (Gross and Levenson 1993), while the use of reappraisal is not (Gross 1998b). Although sympathetic activation is a fundamentally adaptive response to threat, excessive or prolonged arousal can lead to negative long-term outcomes (Lester 1981), providing further evidence that suppression is a less adaptive regulatory strategy overall.

Emotion Regulation in Social Functioning

In recent years, researchers have been particularly interested in the role of emotion regulation in social development. According to Laurent and Rubin (2004), emotion regulation underlies an individual’s physiological and emotional flexibility, which enables them to maintain an optimal level of arousal. In this optimal state, an individual can successfully attend to the socially significant aspects of their environment (Anzalone and Williamson 2000), enhancing their ability to maintain social interactions, communicate effectively, and adapt to changes in their surroundings (Prizant et al. 2003). Effective emotion regulation facilitates the development of these fundamental social skills, as well as other emotional and communicative abilities.

As children develop, their emotional skills (e.g., labeling and managing their own emotions, recognizing the emotions of others, etc.) become increasingly important to the formation of social connections (Saarni 1990). Of these skills, one of the most essential is the ability to inhibit (or regulate) impulsive emotional reactions (Laurent and Rubin 2004) and instead abide by emotional display rules, which dictate the ‘dos and don’ts’ of emotional expression in social contexts. For example, Rydell and colleagues (2003) found that typically-developing children who effectively regulated fear and anger demonstrated increased prosocial behavior and greater social success than those who did not. A similar study found that effortful control, an important aspect of self-regulation, moderated the relationship between preschoolers’ attentional biases (toward sad or angry facial expressions) and their social behaviour: in individuals with low effortful control, greater attention to angry expressions predicted greater levels of aggression, and in individuals with high effortful control, greater attention to sad expressions predicted greater social competence (Nozadi et al. 2017). Research also suggests that early childhood friendships are critical to learning emotional display rules and associated regulatory behaviors (Bauminger et al. 2004), providing further evidence of an association between emotion regulation and effective social functioning.

Social Deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by severe and persistent deficits in social communication and interaction (American Psychiatric Association 2013), as well as restricted and repetitive behaviours, making the formation and maintenance of social relationships very challenging (e.g., Knott et al. 2006). In children and adolescents, these deficits are evidenced by impairments in the core abilities that enable social interaction (Spence 2003), and lead directly to negative social outcomes, such as bullying and isolation (Kloosterman et al. 2013; Rowley et al. 2012; Sofronoff et al. 2011). For example, children with ASD display less joint attention, less eye contact, and less concern to distress than typically-developing (TD) peers (Travis et al. 2001), and struggle to initiate social interactions (Mundy 1995) and maintain friendships beyond early- and middle-childhood (Knott et al. 2006). Additionally, parent- and self-report data from adolescents with ASD has shown considerable agreement regarding specific social difficulties (e.g., social engagement and temper management) relative to social strengths (e.g., making requests politely and apologizing; Knott et al. 2006). In other words, adolescents with ASD were able to engage in structured prosocial skills with clear rules, but had difficulty in engaging with peers in unstructured situations.

In efforts to understand social deficits more broadly, many researchers have assessed the role of physiological arousal, often focusing on behaviorally-inhibited populations (e.g., Biederman et al. 1995; Kagan et al. 1987). Similar to individuals with ASD, behaviorally-inhibited children often display impaired social skills and have difficulty regulating their behavior in the face of mild stressors and novel environments (Biederman et al. 1995). These challenges may be attributed to lower thresholds of physiological arousal, resulting in elevated activity in the sympathetic nervous system (Kagan et al. 1987). This increased arousal makes all types of regulation more difficult, including emotion regulation, leaving the child more vulnerable to negative social experiences and adverse social conditioning (Biederman et al. 1995). Due to various behavioral and social similarities, these findings on behaviorally-inhibited children have been connected to research on children with ASD, who also display elevated levels of physiological arousal (Bellini 2006). As a result, children with ASD may be more susceptible to becoming overwhelmed in social situations, creating further barriers to the formation of social relationships and the practice of fundamental social skills and emotion regulation skills.

In sum, when compared to their TD peers, children and adolescents with ASD show significantly different profiles of physiological arousal and social functioning. As discussed, these two domains of functioning are closely related to one another (i.e., high levels of arousal increase susceptibility to negative social experiences; Biederman et al. 1995). Individual differences in these domains are also associated with different profiles of emotion regulation (Gross 1998b; Gross and Levenson 1993), such that individuals who engage more frequently in suppression experience elevated sympathetic arousal and impaired social functioning (Gross and John 2003). Interestingly, although individuals with ASD show established deficits in many of the areas associated with maladaptive regulation, the role of emotion regulation ability in ASD symptomatology has been largely unexplored.

Emotion Regulation and Impaired Social Functioning in ASD

Although it is not a formal criterion of ASD, impaired emotion regulation can be observed in almost all of the core social and behavioral characteristics, from social anxiety and withdrawal, to intense emotional outbursts in the face of deviation from routine (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Existing research investigating emotion regulation in ASD has focused primarily on identifying a regulatory deficit through comparisons with TD control samples. For example, Samson and colleagues (2015a) found that children and adolescents with ASD engage in significantly more suppression and less reappraisal than their TD peers. Similar studies have shown that children with ASD use fewer adaptive coping strategies, such as reappraisal and acceptance, when dealing with emotional situations (Jahromi et al. 2012; Konstantareas and Stewart 2006; Samson et al. 2015b). More specifically, children with ASD often respond impulsively to emotional events (i.e., with suppression, withdrawal, or outbursts of frustration), rather than choosing appropriate regulatory strategies (Mazefsky et al. 2013).

Although research in TD populations shows reliable associations between maladaptive regulation and various negative outcomes—many of which are also established symptoms of ASD (e.g., elevated physiological arousal, reduced positive affect, poor social relationships; Gross 2002; Knott et al. 2006; Trepagnier 1996)—very few studies have investigated similar associations in ASD populations. In one study, Samson and colleagues (2014) found that in children with ASD, maladaptive emotional behavior was associated with poorer social responsiveness, increased repetitive behaviours, and greater sensory reactivity. However, their measures assessed only emotional behaviour (e.g., physical violence, negative affect, intensity and duration of outbursts, etc.), and do not provide insight into children’s regulation (i.e., their internal use of strategies such as reappraisal or suppression). Samson and colleagues (2016) also found that a common brain region may underlie both the social and affective impairments of adolescents with high-functioning ASD, but that emotion dysregulation was surprisingly not correlated with core ASD symptoms. Other studies have found associations between maladaptive coping strategies and psychiatric symptoms such as depression (Patel et al. 2016; Pouw et al. 2013; Rieffe et al. 2011), but have not investigated associations with ASD symptomatology.

Building on these important findings, it is essential to investigate how emotion regulation deficits may contribute to the general and social impairments of children and adolescents with ASD. For example, adolescents with ASD have particular difficulty with social engagement and temper management (Knott et al. 2006); in contrast to areas where they excel (e.g., making requests politely; Knott et al. 2006), these challenges may often occur in situations that are less structured, and may therefore require greater flexibility and more effortful regulation of emotion and behaviour (e.g., trying to join a game, being teased by a peer, etc.). Thus, emotion regulation deficits may contribute to the symptoms that commonly emerge in these challenging situations (e.g., restricted, repetitive behaviours, emotional outbursts, social withdrawal; American Psychiatric Association 2013). Further, maladaptive coping has been reliably associated with negative psychiatric symptoms in children with ASD, including attention problems, aggression, depression, and anxiety (Patel et al. 2016; Pouw et al. 2013; Rieffe et al. 2011). Mazefsky and colleagues (2014) found that adolescents with ASD who regulated emotion by shutting down or by ruminating on a stressor were more likely to demonstrate internalizing and externalizing problems. More thorough investigation of emotion regulation in ASD populations is imperative to furthering our understanding of ASD symptomatology, and could have significant implications for addressing social impairments and psychiatric co-morbidities.

The Current Study

The existing literature provides support for an emotion regulation deficit in ASD populations, as well as associations between emotional behaviour and ASD symptomatology and between emotion regulation and psychiatric symptomatology. However, to our knowledge, researchers have not yet investigated the direct association between emotion regulation strategies and symptom severity in childhood and adolescent ASD populations. The present study therefore examined whether children’s use of specific emotion regulation strategies predicted ASD symptomatology, with a particular emphasis on social impairment. Though there may be theoretical reasons to suspect an association between emotion regulation and other ASD symptoms (e.g., communication impairments, restricted or repetitive behaviors, etc.), we were specifically interested in social functioning due to its pervasive impairment in ASD, and its established relationship with emotion regulation in the TD literature. In accordance with findings from TD populations, wherein effective emotion regulation has been associated with better general well-being and enhanced social functioning (Gross 2002; Gross and John 2003; Laurent and Rubin 2004), we predicted that more frequent use of reappraisal, rather than suppression, would be associated with less severe ASD symptomatology and less severe social impairment.

Method

Participants

One-hundred-and-forty-five primary caregivers (hereafter referred to as participants) completed all necessary measures, reporting on children and adolescents (111 males) between 5 and 17 years of age (M = 12.30, SD = 3.24). All but four participants reported English as the primary language spoken in the child’s home. Seventy-five children were reported as having co-morbid medical issues or special needs, with the most prevalent being Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; 12% of total sample), anxiety (8%), intellectual disability (8%), and learning disorder (3%)Footnote 1. Participants with co-morbid disorders were included in the final sample, as these individuals are considered representative of the ASD population (e.g., Amaral et al. 2008; Simonoff et al. 2008).

Language ability was measured categorically using parent-report of the child’s primary method of communication (fluent verbal language, short sentences, few words, sign language, communicative device, or non-verbal). All individuals were further divided into three communication levels: 75 children (52%) had fluent verbal language, 40 children (27%) had functional language (short sentences), and 30 children (21%) had limited language (a combination of all remaining categories: few words, sign language, communicative devices, and non-verbal).Footnote 2

Participants were recruited via phone and email using contact information from a university lab database, comprised of families who were previously contacted through recruitment events and had expressed an interest in participating in research. Other university labs and ASD organizations were also invited to distribute the study information to eligible families within their own contact databases. This was thus a community sample.

Measures

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross and John 2003)

Participants completed this ten item Likert-type scale assessing their child’s use of emotion regulation strategies. Responses are made on a seven-point scale ranging from “1 (Strongly Disagree)” to “7 (Strongly Agree)”, with a response of “4” being neutral. Items are divided into two subscales, suppression and reappraisal, and include statements such as “My child keeps his/her emotions to him/herself” and “When my child wants to feel more positive emotion, s/he changes what s/he’s thinking about”. The ERQ was designed as a self-report measure; researchers modified each item to be suitable for parent-report by replacing “I” with “My child” and “my” with “his/her”.

Autism Quotient (AQ; Auyeung et al. 2008; Baron-Cohen et al. 2006)

Participants completed a fifty item Likert-type scale assessing their child’s presentation of ASD symptomatology. Responses are made on a four-point scale including “definitely disagree”, “slightly disagree”, “slightly agree”, and “definitely agree”. Items assess the child’s behavior on five subscales: social skills, attention switching, attention to detail, communication, and imagination. The questionnaire includes statements such as “S/he enjoys social occasions” and “S/he is fascinated by dates”. The caregiver completed one of two versions: the AQ-Child for children ages 5–11 (Auyeung et al. 2008), or the AQ-Adolescent for children ages 12–17 (Baron-Cohen et al. 2006). The two versions contain slight differences in wording or context in order to ensure each item is applicable to the target age group. Although the AQ-Child is typically scored along a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, the present study used the same scoring scheme as the AQ-Adolescent to allow for simultaneous analysis of both age groups (24 items received a score of 1 for agreement responses and a score of 0 for disagreement responses; the remaining 26 items were scored in the reverse direction). Social functioning was measured using the social skills subscale score.

Procedure

Participating families were emailed a link to the online questionnaire package, which was constructed and completed using Fluid Surveys. We used a cross-sectional design, therefore all questionnaire measures were obtained at one time point. The survey package was designed to be completed within a single session of approximately 25–30 min, but allowed participants to save their progress and continue at a later time if necessary. Informed consent was obtained electronically from all individual participants included in the study. Participants were provided with researchers’ contact information and encouraged to request answers to any questions or concerns prior to beginning the study. The study was approved by the University Ethics Board.

All participants completed the same version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), but completed an age-specific version of the Autism Quotient (AQ; the AQ-Child if reporting on a child between ages 5 and 11, or the AQ-Adolescent if reporting on a child between ages 12 and 17). Since the two versions of the AQ were designed to be comparable (Auyeung et al. 2008), both were scored using the AQ-Adolescent scheme, in which responses are coded into two levels (responses in the “autistic direction” and responses in the “non-autistic direction”). AQ data from both age groups were analyzed simultaneously using single variables for each scale or subscale (e.g., AQ Total, AQ Social, etc.).

Results

Descriptive statistics were obtained for all relevant scales and subscales within the ERQ and the AQ, as summarized in Table 1.

Individual differences in age and language level were expected to be covariates of both emotion regulation ability and ASD symptomatology. Correlational analyses found that age was not significantly correlated with scores on the suppression or reappraisal subscales of the ERQ, nor was it correlated with scores on the overall AQ or the social skills subscale of the AQ (all p’s > 0.050; refer to Table 2). Similarly, a multivariate analysis found no significant differences between the three language groups (fluent, functional, and limited) on any of the four scales of interest (reappraisal, suppression, AQ total, AQ social; all p’s > 0.585). Thus, in the interest of maintaining power, age and language level were not considered covariates in the current study and were not statistically controlled for in subsequent analyses. Correlation coefficients for all associations between age, emotion regulation and ASD symptomatology are summarized in Table 2.

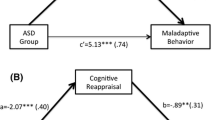

Results of several linear regression analyses found that the use of reappraisal significantly predicted total AQ scores, β = − 0.20, t(143) = − 2.38, p = .019, and explained a significant proportion of variance in total AQ scores, R2 = 0.03, F(1, 143) = 5.66, p = .019, such that individuals who engaged in more frequent reappraisal had less severe ASD symptoms. Similarly, the use of reappraisal significantly predicted scores on the social skills subscale of the AQ, β = − 0.19, t(143) = − 2.37, p = .019, and explained a significant proportion of variance, R2 = 0.03, F(1, 143) = 5.62, p = .019, such that individuals who engaged in more frequent reappraisal had less severe social impairment. In contrast, the use of suppression was not a significant predictor of scores on the overall AQ or the social skills subscale of the AQ (all p’s > 0.192; refer to Table 3).

Notably, although our study was primarily interested in general ASD symptomatology and social functioning, we conducted correlational analyses with the remaining four subscales of the AQ, in order to ensure the significant findings for overall AQ score were not entirely attributable to the social skills subscale. We found that reappraisal was significantly associated with scores on the attention switching subscale, r(143) = − 0.24, p = .008, as well as scores on the communication subscale, r(143) = − 0.22, p = .004. Reappraisal was not significantly correlated with the remaining two subscales (attention to detail and imagination; all p’s > 0.299), and suppression was not significantly correlated with any subscales (all p’s > 0.192; refer to Table 2).

Discussion

In typically-developing populations, the use of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as suppression, has been reliably associated with negative outcomes, including poor socio-emotional flexibility (Laurent and Rubin 2004), reduced social engagement (Prizant et al. 2003), and elevated physiological arousal (Gross and Levenson 1993). Although many of these outcomes are also established symptoms of ASD (American Psychiatric Association 2013; Prizant et al. 2003; Trepagnier 1996), this is, to our knowledge, the first study investigating direct associations between emotion regulation strategies and symptomatology in an ASD population. Building on recent findings of emotion regulation difficulties in ASD (Jahromi et al. 2012; Mazefsky et al. 2013; Samson et al. 2015a, b), and associations between internalizing/externalizing behaviours and ASD symptomatology (Samson et al. 2014), the purpose of the present study was to determine whether regulatory abilities predicted general symptomatology and social impairment in children and adolescents on the autism spectrum.

It was hypothesized that individuals who engaged in more effective emotion regulation would demonstrate less severe ASD symptomatology and less severe social impairment. Results of two linear regression analyses provided support for both hypotheses, such that higher scores on the reappraisal subscale of the ERQ significantly predicted lower total scores on the AQ and lower scores on the social skills subscale. The latter finding indicates that individuals with better emotion regulation abilities demonstrate less severe impairment in social domains, such as the ability to form and maintain friendships, the desire for social interaction, and the enjoyment of social occasions. This is in line with research in TD populations, where a greater emotion regulation capacity has been associated with enhanced socio-emotional flexibility (Laurent and Rubin 2004), resulting in greater attention to one’s social surroundings, more positive social interactions, and improved social communication (Prizant et al. 2003).

In addition to assessing social functioning, the AQ measures ASD symptoms within several domains, including flexibility (e.g., ability to cope with deviations from routine), communication (e.g., turn-taking in conversation), and attention to detail (e.g., noticing changes in the environment). The relationship between reappraisal and total AQ score therefore indicates that challenges across these domains (and others) are less severe for individuals with better emotion regulation skills (i.e., greater use of reappraisal). Once again, this finding aligns with research in TD populations, where reappraisal has been reliably associated with positive outcomes in socio-emotional flexibility, communication, attention, and general well-being (Gross 2002; Gross and John 2003; Laurent and Rubin 2004; Prizant et al. 2003).

Suppression was not significantly predictive of general ASD symptomatology or social functioning, adding to a substantial body of evidence supporting reappraisal as a more adaptive strategy than suppression (Gross 2002; Gross and John 2003). Although we did not form any specific hypotheses regarding suppression, research in TD populations shows that suppression is associated with many negative outcomes (Gross 2002; Gross and Levenson 1993); thus, the non-significant results of the present study may indicate that suppression is not as detrimental to individuals with ASD as it is to their TD peers. This finding also aligns with research from Pouw and colleagues (2013), who found that greater use of avoidant coping strategies predicted more depressive symptoms for TD boys, but fewer depressive symptoms for boys with ASD. One possible explanation for these findings is that deficits in inhibitory control, problem-solving, and communication make it more difficult to learn and use cognitive reappraisal (McRae et al. 2012; Schultz et al. 2001); thus, for individuals with ASD, suppression may often be the only feasible regulatory option. Children and adolescents with ASD may learn, over time, to use suppression more effectively, resulting in fewer negative outcomes relative to their TD peers.

Although our study was specifically interested in overall symptomatology and social functioning, we found that reappraisal was also significantly correlated with attention switching and communication, but not attention to detail or imagination (refer to Table 2). These findings align with the literature in TD populations, where effective emotion regulation has been associated with both executive functioning (e.g., attention switching and set-shifting; McRae et al. 2012) and communication skills (e.g., language and emotion labeling; Schultz et al. 2001; Fujiki et al. 2002; Prizant et al. 2003). These results also suggest that the significant association between reappraisal and total AQ score is not entirely attributable to the social skills subscale (or a biased parent report), providing evidence for a robust relationship between emotion regulation and general ASD symptomatology. Suppression was not significantly correlated with any subscales of the AQ, providing further support for the argument that suppression may be less detrimental to individuals with ASD, relative to their TD peers. Future studies should make use of behavioural paradigms to conduct more detailed empirical investigations of how emotion regulation difficulties impact each ASD symptom subscale.

Notably, the use of reappraisal only explains a small proportion of the variance in ASD symptomatology. However, this is unsurprising given the fact that our outcome measures were very broad (i.e., general ASD symptomatology) and our sample included the full range of the autism spectrum; there are undoubtedly numerous factors and domains of functioning that contribute to the vast variability in ASD symptoms. Our results suggest that impaired emotion regulation ability is one such factor, predicting a small but significant proportion of the variability across general ASD functioning, as well as social functioning, attention, and communication. Subsequent studies should explore the possibility of atypical regulation in ASD, as it is possible that individuals with ASD use very little reappraisal relative to TD populations (Jahromi et al. 2012; Samson et al. 2015a, b), but engage in alternative regulatory behaviours not assessed by the ERQ (Mazefsky et al. 2016). For example, restricted and repetitive behaviours may act as an atypical regulatory mechanism for coping with emotional situations (Samson et al. 2015b). Further inquiry regarding the possibility of atypical regulation is clinically important, and may facilitate the development of regulatory measures that are more sensitive to ASD populations.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study provides preliminary evidence for an association between the use of reappraisal and the severity of ASD symptoms in children and adolescents; however, it is limited by its reliance on parent-report measures. According to Johnson and colleagues (2009), parental biases may be particularly problematic for ASD research, as parents may become increasingly sensitive to their child’s autistic traits, and thus may over-report symptoms on the AQ. Similarly, due to the highly internal nature of the ERQ, parents are required to make inferences about their child’s internal regulatory processes based on the external behaviors they observe. While this is likely difficult for any parent, it may be particularly challenging for parents of children with lower-functioning ASD, who may be less likely to follow up on their child’s emotional reactions due to cognitive or linguistic limitations. For example, after a conflict or emotional outburst, parents of TD or high-functioning children may ask questions in efforts to understand their child’s perspective; parents of children with lower-functioning ASD may be less likely to engage in this type of conversation, and therefore less likely to gain insight into how their child is thinking or feeling during emotional events. Individual differences in language ability were also expected to play a role in individuals’ symptom severity and emotion regulation ability; however, we found no significant differences between our three language groups. This may be due to the categorical parent-report measure of language (i.e., asking parents to select one of several communication options).

Despite this limitation, the use of parent-report has enabled us to assess a larger sample and a wider range of children than would be possible with many behavioural or self-report measures, including individuals across a wide age range and across the entire autism spectrum. Our findings provide preliminary evidence for a significant association between the use of reappraisal and the severity of ASD symptoms, and motivate further exploration of the relationship using behavioural paradigms. Future research should obtain objective measures of language and ASD symptomatology, and should assess emotion regulation more comprehensively, using all three aspects of the emotional experience (i.e., self-report measures of cognitive appraisals and feelings, psychophysiological measures of arousal, and observational measures of behaviour). One final limitation is the cross-sectional nature of this study; however, given the anonymous nature of our data collection, it was not possible to obtain longitudinal measures from participants. Future studies would benefit from a longitudinal design, enabling the investigation of potential causal mechanisms for the relationship between emotion regulation and ASD symptom severity.

Future research should also aim to develop emotion regulation training techniques that can be adapted for ASD populations and incorporated into intervention programs. Emotion regulation capacity is associated with physiological and emotional flexibility, influencing one’s ability to adapt to changing social environments and maintain social interactions (Laurent and Rubin 2004; Prizant et al. 2003). Emotion regulation difficulties in individuals with ASD may therefore contribute to challenges with interpreting and adapting to the social environment. Further, reduced flexibility may have direct implications for other ASD symptoms, including cognitive rigidity, impaired attention switching, and emotional outbursts, creating further indirect effects for social functioning (e.g., negative perception from peers, bullying, etc.). Maladaptive emotion regulation has also been reliably associated with increased psychiatric symptoms in youth with ASD, including aggression, anxiety, and depression (Mazefsky et al. 2014; Patel et al. 2016; Pouw et al. 2013; Rieffe et al. 2011). Improvements in emotion regulation may therefore lead to significant improvements in social, cognitive, and behavioral functioning, and reduce internalizing and externalizing behaviours in children and adolescents with ASD. Although reappraisal is a higher-order process and may present challenges for individuals with cognitive limitations, incorporating the fundamental skills underlying reappraisal (e.g., expressing emotions with words rather than actions, discerning malicious transgressions from accidental ones, etc.) into early intervention programs may have positive and lasting impacts for children on the autism spectrum.

Conclusions

The current study adds to a limited but growing body of literature regarding emotion regulation in ASD populations, and provides empirical evidence of a predictive association between the use of adaptive regulatory strategies and ASD symptomatology in children and adolescents. We have demonstrated that for youth with ASD, more frequent use of reappraisal predicts less severe ASD symptoms and, more specifically, less severe social impairment. In contrast, frequent use of suppression showed no significant associations with symptom severity. Taken together with recent findings of an emotion regulation deficit in ASD (e.g., Samson et al. 2015a), these results suggest that impairments in emotion regulation may underlie various domains of ASD symptomatology, and that increasing children’s use of reappraisal may have positive consequences on their social and general functioning. Behavioural and physiological explorations of emotion regulation in children and adolescents with ASD may lead to the development of ASD-specific measures and training strategies, with significant potential for reducing symptom severity.

Notes

Although 75 participants selected “Yes” to indicate that their child had co-morbid issues, not all participants provided specific details. The sample also included various other co-morbidities, reported with lower frequency.

Language ability was measured categorically, as previous research in our lab using online survey methods has found it challenging to obtain accurate parent-report of formal test scores (i.e., vocabulary, verbal IQ).

References

Aldao, A., Jazaieri, H., Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies: Interactive effects during CBT for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 382–389.

Amaral, D. G., Schumann, C. M., & Nordahl, C. W. (2008). Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends in Neuroscience, 31, 137–145.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edn.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Anzalone, M., & Williamson, G. (2000). Sensory processing and motor performance in autism spectrum disorders. In A. M. Wetherby & B. M. Prizant (Eds.), Autism spectrum disorders: A transactional developmental perspective (pp. 142–166). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Auyeung, B., Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., & Allison, C. (2008). The autism spectrum quotient: Children’s version (AQ-Child). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1230–1240.

Baron-Cohen, S., Hoekstra, R. A., Knickmeyer, R., & Wheelwright, S. (2006). The autism-spectrum quotient—Adolescent version (AQ-Adolescent). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 343–350.

Bauminger, N., Shulman, C., & Agam, G. (2004). The link between perceptions of self and of social relationships in high-functioning children with autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 16, 193–214.

Bellini, S. (2006). The development of social anxiety in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 21, 138–145.

Biederman, J., Rosenbaum, J. F., Chaloff, J., & Kagan, J. (1995). Behavioural inhibition as a risk factor for anxiety disorders. In J. S. March (Ed.), Anxiety in children and adolescents (pp. 61–81). New York: Guilford Press.

Fujiki, M., Brinton, B., & Clarke, D. (2002). Emotion regulation in children with specific language impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 33, 102–111.

Gross, J. J. (1998a). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 224–237.

Gross, J. J. (1998b). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2, 271–299.

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39, 281–291.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362.

Gross, J. J., & Levenson, R. W. (1993). Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report and expressive behaviour. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 970–986.

Jahromi, L. B., Meek, S. E., & Ober-Reynolds, S. (2012). Emotion regulation in the context of frustration in children with high functioning autism and their typical peers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 1250–1258.

Johnson, S. A., Filliter, J. H., & Murphy, R. R. (2009). Discrepancies between self- and parent-perceptions of autistic traits and empathy in high functioning children and adolescents on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1706–1714.

Kagan, J., Reznick, J. S., & Snidman, N. (1987). The physiology and psychology of behavioural inhibition in children. Child Development, 58, 1459–1473.

Kloosterman, P. H., Kelley, E., Craig, W. M., Parker, J. A., & Javier, C. (2013). Types and experiences of bullying in adolescents with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 824–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.02.013.

Knott, F., Dunlop, A., & Mackay, T. (2006). Living with ASD: How do children and their parents assess their difficulties with social interaction and understanding? Autism, 10, 609–617.

Konstantareas, M. M., & Stewart, K. (2006). Affect regulation and temperament in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 143–154.

Laurent, A. C., & Rubin, E. (2004). Challenges in emotional regulation in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Topics in Language Disorders, 24, 286–297.

Lazarus, R. S., & Alfert, E. (1964). Short-circuiting of threat by experimentally altering cognitive appraisal. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 69, 195–205.

Lester, D. (1981). Neuroticism, psychoticism, and autonomic nervous system balance. Biological Psychiatry, 16, 683–685.

Mazefsky, C. A., Borue, X., Day, T. N., & Minshew, N. J. (2014). Emotion regulation patterns in adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: Comparison to typically developing adolescents and association with psychiatric symptoms. Autism Research, 7, 344–354.

Mazefsky, C. A., Day, T. N., Siegel, M., White, S. W., Yu, L., & Pilkonis, P. A. (2016). Development of the emotion dysregulation inventory: A PROMIS®ing method for creating sensitive and unbiased questionnaires for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2907-1.

Mazefsky, C. A., Herrington, J., Siegel, M., Scarpa, A., Maddox, B. B., Scahill, L., & White, S. W. (2013). The role of emotion regulation in autism spectrum disorder. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 679–688.

McRae, K., Jacobs, S. E., Ray, R. D., John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Individual differences in reappraisal ability: Links to reappraisal frequency, well-being, and cognitive control. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 2–7.

Mundy, P. (1995). Joint attention and social-emotional approach behaviour in children with autism. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 63–82.

Nozadi, S. S., Spinrad, T. L., Johnson, S. P., & Eisengerg, N. (2017). Relations of emotion-related temperamental characteristics to attentional biases and social functioning. Emotion, https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000360.

Patel, S., Day, T. N., Jones, N., & Mazefsky, C. A. (2016). Association between anger rumination and autism symptom severity, depression symptoms, aggression, and general dysregulation in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21, 181–189.

Pouw, L. B. C., Rieffe, C., Stockman, A. P. A. M., & Gadow, K. D. (2013). The link between emotion regulation, social functioning, and depression in boys with ASD. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 549–556.

Prizant, B. M., Wetherby, A. M., Rubin, E., & Laurent, A. C. (2003). The SCERTS model: A family-centered, transactional approach to enhancing communication and socioemotional abilities of young children with ASD. Infants and Young Children, 16, 296–316.

Rieffe, C., Oosterveld, P., Terwogt, M. M., Mootz, S., van Leeuwen, E., & Stockmann, L. (2011). Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 15, 655–670.

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications, and theory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Rowley, E., Chandler, S., Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Loucas, T., & Charman, T. (2012). The experience of friendship, victimization and bullying in children with an autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child characteristics and school placement. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 1126–1134.

Rydell, A., Berlin, L., & Bohlin, G. (2003). Emotionality, emotion regulation, and adaptation among 5- to 8-year-old children. Emotion, 3, 30–47.

Saarni, C. (1990). Emotional competence: How emotions and relationships become integrated. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1988: Socioemotional Development, 36, 115–182.

Samson, A. C., Dougherty, R. F., Lee, I. A., Phillips, J. M., Gross, J. J., & Hardan, A. Y. (2016). White matter structure in the uncinate fasciculus: Implications for socio-affective deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 255, 66–74.

Samson, A. C., Hardan, A. Y., Podell, R. W., Phillips, J. M., & Gross, J. J. (2015a). Emotion regulation in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 8, 9–18.

Samson, A. C., Phillips, J. M., Parker, K. J., Shah, S., Gross, J. J., & Hardan, A. Y. (2014). Emotion dysregulation and the core features of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 1766–1772.

Samson, A. C., Wells, W. M., Phillips, J. M., Hardan, A. Y., & Gross, J. J. (2015b). Emotion regulation in autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from parent interviews and children’s daily diaries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 903–913.

Schultz, D., Izard, C., & Ackerman, B. (2001). Emotion knowledge in economically disadvantaged children: Self-regulatory antecedents and relations to social difficulties and withdrawal. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 56–67.

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 921–929.

Sofronoff, K., Dark, E., & Stone, V. (2011). Social vulnerability and bullying in children with Asperger syndrome. Autism, 15, 355–372.

Spence, S. (2003). Social skills training with children and young people: Theory, evidence and practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 8, 84–96.

Thomspon, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 25–52.

Travis, L., Sigman, M., & Ruskin, E. (2001). Links between social understanding and social behaviour in verbally able children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 119–130.

Trepagnier, C. (1996). A possible origin for the social and communicative deficits of autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 11, 170–182.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rosaria Furlano for her help with statistical analyses. We would also like to thank all of the families who took time out of their busy schedules to respond to this survey. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SFG was the primary author of this article; EK provided theoretical and editorial guidance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Electronic Supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goldsmith, S.F., Kelley, E. Associations Between Emotion Regulation and Social Impairment in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 48, 2164–2173 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3483-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3483-3